Defense

of chanting Edit

John Daido Loori justified the use of chanting sutras by referring to

Zen master Dōgen.[11] Dōgen is known to have refuted the statement

“Painted rice cakes will not satisfy hunger”. This statement means that

sutras, which are just symbols like painted rice cakes, cannot truly

satisfy one’s spiritual hunger. Dōgen, however, saw that there is no

separation between metaphor and reality. “There is no difference between

paintings, rice cakes, or any thing at all”.[12] The symbol and the

symbolized were inherently the same, and thus only the sutras could

truly satisfy one’s spiritual needs.

To understand this non-dual relationship experientially, one is told to

practice liturgy intimately.[13] In distinguishing between ceremony and

liturgy, Dōgen states, “In ceremony there are forms and there are

sounds, there is understanding and there is believing. In liturgy there

is only intimacy.” The practitioner is instructed to listen to and speak

liturgy not just with one sense, but with one’s “whole body-and-mind”.

By listening with one’s entire being, one eliminates the space between

the self and the liturgy. Thus, Dōgen’s instructions are to “listen with

the eye and see with the ear”. By focusing all of one’s being on one

specific practice, duality is transcended. Dōgen says, “Let go of the

eye, and the whole body-and-mind are nothing but the eye; let go of the

ear, and the whole universe is nothing but the ear.” Chanting intimately

thus allows one to experience a non-dual reality. The liturgy used is a

tool to allow the practitioner to transcend the old conceptions of self

and other. In this way, intimate liturgy practice allows one to realize

emptiness (sunyata), which is at the heart of Zen Buddhist teachings.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buddhist_chant

There are, bhikkhus, these five drawbacks of reciting the Dhamma with a

sustained melodic intonation.

Which five?

1. Oneself gets attached to that intonation,

2. others get attached to that

intonation,

3.householders get angry:

4. ‘Those ascetics who are followers of the Sakyans’ son sing in the

same way that we do!’,

5. there is a break in concentration for those striving [to produce]

musicality, and the

upcoming generations imitate what they see.

These, bhikkhus, are the five drawbacks of reciting the Dhamma with a

sustained melodic intonation.

Those monks who are followers of the Sakyans’ son chant in the same

way that Buddha and monks do

Traditional chanting Edit

In Buddhism, chanting is the traditional means of preparing the mind for

meditation, especially as part of formal practice (in either a lay or

monastic context). Some forms of Buddhism also use chanting for

ritualistic purposes.

While the basis for most Theravada chants is the Pali Canon, Mahayana

and Vajrayana chants draw from a wider range of sources.

Theravada chants Edit

Buddhist monks chanting

In the Theravada tradition, chanting is usually done in Pali, sometimes

with vernacular translations interspersed.[1] Among the most popular

Theravada chants[1] are:

Buddhabhivadana (Preliminary Reverence for the Buddha)[2]

Tiratana (The Three Refuges)[3]

Pancasila (The Five Precepts)[3]

Buddha Vandana (Salutation to the Buddha)[4]

Dhamma Vandana (Salutation to his Teaching)[5]

Sangha Vandana (Salutation to his Community of Noble Disciples)[6]

Upajjhatthana (The Five Remembrances)[7]

Metta Sutta (Discourse on Loving Kindness)[8]

Reflection on the Body (recitation of the 32 parts of the body).

The traditional chanting in Khmer Buddhism is called Smot.[9]

Mahayana sutra chants Edit

Chanting in the sutra hall

Since Japanese Buddhism is divided in thirteen doctrinal schools, and

since Chan Buddhism, Zen and Buddhism in Vietnam – although sharing a

common historical origin and a common doctrinal content – are divided

according to geographical borders, there are several different forms of

arrangements of scriptures to chant within Mahayana Buddhism.:

Daily practice in Nichiren buddhism is chanting the five character of

Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō (homage to the true dharma of the Lotus Sutra). A

Mahayana sutra that reveals the true identity of Shakyamuni as a Buddha

who attained enlightenment numberless kalpas ago. Kumarajiva’s

translation, which is widely honoured, is entitled the Lotus Sutra of

the wonderful law (Myoho Renge Kyo). The mystic relationship between the

law and the lives of the people courses eternally through past,

present, and future, unbroken in any lifetime. In terms of space, the

Nichiren proclaims that the heritage of the ultimate law flows within

lives of his disciples and lay supporters who work in perfect unity for

the realization of a peaceful world and happiness for all humanity.

Nichiren practitioners will chant Nam Myoho Renge Kyo - the true aspect

of all the phenomena and recite certain chapters from the Lotus Sutra,

in particular the 2nd and 16th chapters.

Pure Land Buddhists chant nianfo, Namu Amida Butsu or Namo Amituofo

(Homage to Amitabha Buddha). In more formal services, practitioners will

also chant excerpts from the Larger Sutra of Immeasurable Life or

occasionally the entire Smaller Sutra of Immeasurable Life (a sutra not

unique for Pure Land Buddhism, but chanted in the evening by

Chan-buddhists and Tendai-buddhists as well).

Popular with Zen, Shingon or other Mahayana practitioners is chanting

the Prajñāpāramitā Hridaya Sūtra (Heart Sutra), especially during

morning offices. In more formal settings, larger discourses of the

Buddha (such as the Diamond Sutra in Zen temples and the Lotus Sutra in

Tendai temples) may be chanted as well.

Particularly in the Chinese, Vietnamese and the Japanese traditions,

repentance ceremonies, involving paying deep reverence to the buddhas

and bodhisattvas, as well as executing rituals to rescue and feed hungry

ghosts, are also occasionally practiced. There is no universally used

form for these two practices, but several different forms, the use of

which follows doctrinal and geographical borders. Within Chan, it is

common to chant Sanskrit formulae, known as dhāraṇīs, especially in the

morning.

Vajrayana chants Edit

In the Vajrayana tradition, chanting is also used as an invocative

ritual in order to set one’s mind on a deity, Tantric ceremony, mandala,

or particular concept one wishes to further in themselves.

For Vajrayana practitioners, the chant Om Mani Padme Hum is very popular

around the world as both a praise of peace and the primary mantra of

Avalokitesvara. Other popular chants include those of Tara,

Bhaisajyaguru, and Amitabha.

Tibetan monks are noted for their skill at throat-singing, a specialized

form of chanting in which, by amplifying the voice’s upper partials,

the chanter can produce multiple distinct pitches simultaneously.

Japanese esoteric practitioners also practice a form of chanting called

shomyo.

Non-canonical uses of Buddhist chanting Edit

There are also a number of New Age and experimental schools related to

Buddhist thought which practise chanting, some with understanding of the

words, others merely based on repetition. A large number of these

schools tend to be syncretic and incorporate Hindu japa and other such

traditions alongside the Buddhist influences.

While not strictly a variation of Buddhist chanting in itself, Japanese

Shigin (詩吟) is a form of chanted poetry that reflects several principles

of Zen Buddhism. It is sung in the seiza position, and participants are

encouraged to sing from the gut - the Zen locus of power. Shigin and

related practices are often sung at Buddhist ceremonies and

quasi-religious gatherings in Japan.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gautama_Buddha

Gautama Buddha

Language

Watch

Edit

Not to be confused with the Chinese monk Budai (the “laughing Buddha”)

or Budha in Hindu astrology.

For the film, see Gautama Buddha (film).

“Buddha” and “Gautama” redirect here. For the Buddhist title, see Buddha

(title). For other uses, see Buddha (disambiguation) and Gautama

(disambiguation).

The Buddha (also known as Siddhattha Gotama or Siddhārtha Gautama[note

3] or Buddha Shakyamuni) was a philosopher, mendicant, meditator,

spiritual teacher, and religious leader who lived in Ancient India (c.

5th to 4th century BCE).[5][6][7][note 4] He is revered as the founder

of the world religion of Buddhism, and worshipped by most Buddhist

schools as the Enlightened One who has transcended Karma and escaped the

cycle of birth and rebirth.[8][9][10] He taught for around 45 years and

built a large following, both monastic and lay.[11] His teaching is

based on his insight into duḥkha (typically translated as “suffering”)

and the end of dukkha – the state called Nibbāna or Nirvana.

Gautama Buddha

Buddha in Sarnath Museum (Dhammajak Mutra).jpg

A statue of the Buddha from Sarnath, Uttar Pradesh, India, circa 475 CE.

The Buddha is depicted teaching in the lotus position, while making the

Dharmacakra mudrā.

Sanskrit name

Sanskrit

Siddhārtha Gautama

Pali name

Pali

Siddhattha Gotama

Other names

Shakyamuni (”Sage of the Shakyas”)

Personal

Born

Siddhartha Gautama

c. 563 BCE or 480 BCE

Lumbini, Shakya Republic (according to Buddhist tradition)[note 1]

Died

c. 483 BCE or 400 BCE (aged 80)[1][2][3]

Kushinagar, Malla Republic (according to Buddhist tradition)[note 2]

Religion

Buddhism

Spouse

Yasodharā

Children

Rāhula

Parents

Śuddhodana (father)

Maya Devi (mother)

Known for

Founder of Buddhism

Other names

Shakyamuni (”Sage of the Shakyas”)

Senior posting

Predecessor

Kassapa Buddha

Successor

Maitreya

The Buddha was born into an aristocratic family in the Shakya clan but

eventually renounced lay life. According to Buddhist tradition, after

several years of mendicancy, meditation, and asceticism, he awakened to

understand the mechanism which keeps people trapped in the cycle of

rebirth. The Buddha then traveled throughout the Ganges plain teaching

and building a religious community. The Buddha taught a middle way

between sensual indulgence and the severe asceticism found in the Indian

śramaṇa movement.[12] He taught a spiritual path that included ethical

training and meditative practices such as jhana and mindfulness. The

Buddha also critiqued the practices of Brahmin priests, such as animal

sacrifice.

A couple of centuries after his death he came to be known by the title

Buddha, which means “Awakened One” or “Enlightened One”.[13] Gautama’s

teachings were compiled by the Buddhist community in the Suttas, which

contain his discourses, and the Vinaya, his codes for monastic practice.

These were passed down in Middle-Indo Aryan dialects through an oral

tradition.[14][15] Later generations composed additional texts, such as

systematic treatises known as Abhidharma, biographies of the Buddha,

collections of stories about the Buddha’s past lives known as Jataka

tales, and additional discourses, i.e, the Mahayana sutras.[16][17]

Names and titles

Besides “Buddha” and the name Siddhārtha Gautama (Pali: Siddhattha

Gotama), he was also known by other names and titles, such as Shakyamuni

(”Sage of the Shakyas”).[18][note 5]

In the early texts, the Buddha also often refers to himself as Tathāgata

(Sanskrit: [tɐˈtʰaːɡɐtɐ]). The term is often thought to mean either

“one who has thus gone” (tathā-gata) or “one who has thus come”

(tathā-āgata), possibly referring to the transcendental nature of the

Buddha’s spiritual attainment.[19]

A common list of epithets are commonly seen together in the canonical

texts, and depict some of his spiritual qualities:[20]

Sammasambuddho – Perfectly self-awakened

Vijja-carana-sampano – Endowed with higher knowledge and ideal conduct.

Sugato – Well-gone or Well-spoken.

Lokavidu – Knower of the many worlds.

Anuttaro Purisa-damma-sarathi – Unexcelled trainer of untrained people.

Satthadeva-Manussanam – Teacher of gods and humans.

Bhagavathi – The Blessed one

Araham – Worthy of homage. An Arahant is “one with taints destroyed, who

has lived the holy life, done what had to be done, laid down the

burden, reached the true goal, destroyed the fetters of being, and is

completely liberated through final knowledge.”

Jina – Conqueror. Although the term is more commonly used to name an

individual who has attained liberation in the religion Jainism, it is

also an alternative title for the Buddha.[21]

The Pali Canon also contains numerous other titles and epithets for the

Buddha, including: All-seeing, All-transcending sage, Bull among men,

The Caravan leader, Dispeller of darkness, The Eye, Foremost of

charioteers, Foremost of those who can cross, King of the Dharma

(Dharmaraja), Kinsman of the Sun, Helper of the World (Lokanatha), Lion

(Siha), Lord of the Dhamma, Of excellent wisdom (Varapañña), Radiant

One, Torchbearer of mankind, Unsurpassed doctor and surgeon, Victor in

battle, and Wielder of power.[22]

Historical person

Scholars are hesitant to make unqualified claims about the historical

facts of the Buddha’s life. Most people accept that the Buddha lived,

taught, and founded a monastic order during the Mahajanapada era during

the reign of Bimbisara (c. 558 – c. 491 BCE, or c. 400 BCE),[23][24][25]

the ruler of the Magadha empire, and died during the early years of the

reign of Ajatashatru, who was the successor of Bimbisara, thus making

him a younger contemporary of Mahavira, the Jain tirthankara.[26][27]

While the general sequence of “birth, maturity, renunciation, search,

awakening and liberation, teaching, death” is widely accepted,[28] there

is less consensus on the veracity of many details contained in

traditional biographies.[29][30][31]

The times of Gautama’s birth and death are uncertain. Most historians in

the early 20th century dated his lifetime as c. 563 BCE to 483

BCE.[1][32] Within the Eastern Buddhist tradition of China, Vietnam,

Korea and Japan, the traditional date for the death of the Buddha was

949 B.C.[1] According to the Ka-tan system of time calculation in the

Kalachakra tradition, Buddha is believed to have died about 833 BCE.[33]

More recently his death is dated later, between 411 and 400 BCE, while

at a symposium on this question held in 1988,[34][35][36] the majority

of those who presented definite opinions gave dates within 20 years

either side of 400 BCE for the Buddha’s death.[1][37][note 4] These

alternative chronologies, however, have not been accepted by all

historians.[43][44][note 6]

Historical context

Historical context

Ancient kingdoms and cities of India during the time of the Buddha

(circa 500 BCE)

According to the Buddhist tradition, Gautama was born in Lumbini, now in

modern-day Nepal, and raised in Kapilavastu, which may have been either

in what is present-day Tilaurakot, Nepal or Piprahwa, India.[note 1]

According to Buddhist tradition, he obtained his enlightenment in Bodh

Gaya, gave his first sermon in Sarnath, and died in Kushinagar.

One of Gautama’s usual names was “Sakamuni” or “Sakyamunī” (”Sage of the

Shakyas”). This and the evidence of the early texts suggests that he

was born into the Shakya clan, a community that was on the periphery,

both geographically and culturally, of the eastern Indian subcontinent

in the 5th century BCE.[65] The community was either a small republic,

or an oligarchy. His father was an elected chieftain, or oligarch.[65]

Bronkhorst calls this eastern culture Greater Magadha and notes that

“Buddhism and Jainism arose in a culture which was recognized as being

non-Vedic”.[66]

The Shakyas were an eastern sub-Himalayan ethnic group who were

considered outside of the Āryāvarta and of ‘mixed origin’

(saṃkīrṇa-yonayaḥ, possibly part Aryan and part indigenous). The laws of

Manu treats them as being non Aryan. As noted by Levman, “The

Baudhāyana-dharmaśāstra (1.1.2.13–4) lists all the tribes of Magadha as

being outside the pale of the Āryāvarta; and just visiting them required

a purificatory sacrifice as expiation” (In Manu 10.11, 22).[67] This is

confirmed by the Ambaṭṭha Sutta, where the Sakyans are said to be

“rough-spoken”, “of menial origin” and criticised because “they do not

honour, respect, esteem, revere or pay homage to Brahmans.” [67] Some of

the non-Vedic practices of this tribe included incest (marrying their

sisters), the worship of trees, tree spirits and nagas.[67] According to

Levman “while the Sakyans’ rough speech and Munda ancestors do not

prove that they spoke a non-Indo-Aryan language, there is a lot of other

evidence suggesting that they were indeed a separate ethnic (and

probably linguistic) group.”[67] Christopher I. Beckwith identifies the

Shakyas as Scythians.[68]

Apart from the Vedic Brahmins, the Buddha’s lifetime coincided with the

flourishing of influential Śramaṇa schools of thought like Ājīvika,

Cārvāka, Jainism, and Ajñana.[69] Brahmajala Sutta records sixty-two

such schools of thought. In this context, a śramaṇa refers to one who

labors, toils, or exerts themselves (for some higher or religious

purpose). It was also the age of influential thinkers like Mahavira,[70]

Pūraṇa Kassapa, Makkhali Gosāla, Ajita Kesakambalī, Pakudha Kaccāyana,

and Sañjaya Belaṭṭhaputta, as recorded in Samaññaphala Sutta, whose

viewpoints the Buddha most certainly must have been acquainted

with.[71][72][note 8] Indeed, Śāriputra and Moggallāna, two of the

foremost disciples of the Buddha, were formerly the foremost disciples

of Sañjaya Belaṭṭhaputta, the sceptic;[74] and the Pali canon frequently

depicts Buddha engaging in debate with the adherents of rival schools

of thought. There is also philological evidence to suggest that the two

masters, Alara Kalama and Uddaka Rāmaputta, were indeed historical

figures and they most probably taught Buddha two different forms of

meditative techniques.[75] Thus, Buddha was just one of the many śramaṇa

philosophers of that time.[76] In an era where holiness of person was

judged by their level of asceticism,[77] Buddha was a reformist within

the śramaṇa movement, rather than a reactionary against Vedic

Brahminism.[78]

Historically, the life of the Buddha also coincided with the Achaemenid

conquest of the Indus Valley during the rule of Darius I from about

517/516 BCE.[79] This Achaemenid occupation of the areas of Gandhara and

Sindh, which lasted about two centuries, was accompanied by the

introduction of Achaemenid religions, reformed Mazdaism or early

Zoroastrianism, to which Buddhism might have in part reacted.[79] In

particular, the ideas of the Buddha may have partly consisted of a

rejection of the “absolutist” or “perfectionist” ideas contained in

these Achaemenid religions.[79]

Earliest sources

Main article: Early Buddhist Texts

The words “Bu-dhe” (𑀩𑀼𑀥𑁂, the Buddha) and “Sa-kya-mu-nī ” (

𑀲𑀓𑁆𑀬𑀫𑀼𑀦𑀻, “Sage of the Shakyas”) in Brahmi script, on Ashoka’s

Lumbini pillar inscription (circa 250 BCE)

No written records about Gautama were found from his lifetime or from

the one or two centuries thereafter. But from the middle of the 3rd

century BCE, several Edicts of Ashoka (reigned c. 269–232 BCE) mention

the Buddha, and particularly Ashoka’s Lumbini pillar inscription

commemorates the Emperor’s pilgrimage to Lumbini as the Buddha’s

birthplace, calling him the Buddha Shakyamuni (Brahmi script: 𑀩𑀼𑀥

𑀲𑀓𑁆𑀬𑀫𑀼𑀦𑀻 Bu-dha Sa-kya-mu-nī, “Buddha, Sage of the

Shakyas”).[80] Another one of his edicts (Minor Rock Edict No. 3)

mentions the titles of several Dhamma texts (in Buddhism, “dhamma” is

another word for “dharma”),[81] establishing the existence of a written

Buddhist tradition at least by the time of the Maurya era. These texts

may be the precursor of the Pāli Canon.[82][83][note 9]

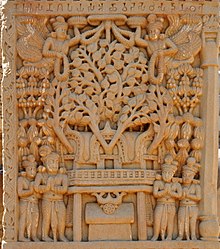

Bharhut inscription: Bhagavato Sakamunino Bodho (𑀪𑀕𑀯𑀢𑁄

𑀲𑀓𑀫𑀼𑀦𑀺𑀦𑁄 𑀩𑁄𑀥𑁄 “The illumination of the Blessed Sakamuni”),

circa 100 BCE.[84]

“Sakamuni” is also mentioned in the reliefs of Bharhut, dated to circa

100 BCE, in relation with his illumination and the Bodhi tree, with the

inscription Bhagavato Sakamunino Bodho (”The illumination of the Blessed

Sakamuni”).[84]

The oldest surviving Buddhist manuscripts are the Gandhāran Buddhist

texts, found in Afghanistan and written in Gāndhārī, they date from the

first century BCE to the third century CE.[85]

On the basis of philological evidence, Indologist and Pali expert Oskar

von Hinüber says that some of the Pali suttas have retained very archaic

place-names, syntax, and historical data from close to the Buddha’s

lifetime, including the Mahāparinibbāṇa Sutta which contains a detailed

account of the Buddha’s final days. Hinüber proposes a composition date

of no later than 350–320 BCE for this text, which would allow for a

“true historical memory” of the events approximately 60 years prior if

the Short Chronology for the Buddha’s lifetime is accepted (but he also

points out that such a text was originally intended more as hagiography

than as an exact historical record of events).[86][87]

John S. Strong sees certain biographical fragments in the canonical

texts preserved in Pali, as well as Chinese, Tibetan and Sanskrit as the

earliest material. These include texts such as the “Discourse on the

Noble Quest” (Pali: Ariyapariyesana-sutta) and its parallels in other

languages.[88]

Traditional biographies

One of the earliest anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha, here

surrounded by Brahma (left) and Śakra (right). Bimaran Casket, mid-1st

century CE, British Museum.[89][90]

Biographical sources

The sources which present a complete picture of the life of Siddhārtha

Gautama are a variety of different, and sometimes conflicting,

traditional biographies. These include the Buddhacarita, Lalitavistara

Sūtra, Mahāvastu, and the Nidānakathā.[91] Of these, the

Buddhacarita[92][93][94] is the earliest full biography, an epic poem

written by the poet Aśvaghoṣa in the first century CE.[95] The

Lalitavistara Sūtra is the next oldest biography, a

Mahāyāna/Sarvāstivāda biography dating to the 3rd century CE.[96] The

Mahāvastu from the Mahāsāṃghika Lokottaravāda tradition is another major

biography, composed incrementally until perhaps the 4th century CE.[96]

The Dharmaguptaka biography of the Buddha is the most exhaustive, and

is entitled the Abhiniṣkramaṇa Sūtra,[97] and various Chinese

translations of this date between the 3rd and 6th century CE. The

Nidānakathā is from the Theravada tradition in Sri Lanka and was

composed in the 5th century by Buddhaghoṣa.[98]

The earlier canonical sources include the Ariyapariyesana Sutta (MN 26),

the Mahāparinibbāṇa Sutta (DN 16), the Mahāsaccaka-sutta (MN 36), the

Mahapadana Sutta (DN 14), and the Achariyabhuta Sutta (MN 123), which

include selective accounts that may be older, but are not full

biographies. The Jātaka tales retell previous lives of Gautama as a

bodhisattva, and the first collection of these can be dated among the

earliest Buddhist texts.[99] The Mahāpadāna Sutta and Achariyabhuta

Sutta both recount miraculous events surrounding Gautama’s birth, such

as the bodhisattva’s descent from the Tuṣita Heaven into his mother’s

womb.

Nature of traditional depictions

Nature of traditional depictions

Māyā miraculously giving birth to Siddhārtha. Sanskrit, palm-leaf

manuscript. Nālandā, Bihar, India. Pāla period

In the earliest Buddhist texts, the nikāyas and āgamas, the Buddha is

not depicted as possessing omniscience (sabbaññu)[100] nor is he

depicted as being an eternal transcendent (lokottara) being. According

to Bhikkhu Analayo, ideas of the Buddha’s omniscience (along with an

increasing tendency to deify him and his biography) are found only

later, in the Mahayana sutras and later Pali commentaries or texts such

as the Mahāvastu.[100] In the Sandaka Sutta, the Buddha’s disciple

Ananda outlines an argument against the claims of teachers who say they

are all knowing [101] while in the Tevijjavacchagotta Sutta the Buddha

himself states that he has never made a claim to being omniscient,

instead he claimed to have the “higher knowledges” (abhijñā).[102] The

earliest biographical material from the Pali Nikayas focuses on the

Buddha’s life as a śramaṇa, his search for enlightenment under various

teachers such as Alara Kalama and his forty-five-year career as a

teacher.[103]

Traditional biographies of Gautama often include numerous miracles,

omens, and supernatural events. The character of the Buddha in these

traditional biographies is often that of a fully transcendent (Skt.

lokottara) and perfected being who is unencumbered by the mundane world.

In the Mahāvastu, over the course of many lives, Gautama is said to

have developed supramundane abilities including: a painless birth

conceived without intercourse; no need for sleep, food, medicine, or

bathing, although engaging in such “in conformity with the world”;

omniscience, and the ability to “suppress karma”.[104] As noted by

Andrew Skilton, the Buddha was often described as being superhuman,

including descriptions of him having the 32 major and 80 minor marks of a

“great man,” and the idea that the Buddha could live for as long as an

aeon if he wished (see DN 16).[105]

The ancient Indians were generally unconcerned with chronologies, being

more focused on philosophy. Buddhist texts reflect this tendency,

providing a clearer picture of what Gautama may have taught than of the

dates of the events in his life. These texts contain descriptions of the

culture and daily life of ancient India which can be corroborated from

the Jain scriptures, and make the Buddha’s time the earliest period in

Indian history for which significant accounts exist.[106] British author

Karen Armstrong writes that although there is very little information

that can be considered historically sound, we can be reasonably

confident that Siddhārtha Gautama did exist as a historical figure.[107]

Michael Carrithers goes a bit further by stating that the most general

outline of “birth, maturity, renunciation, search, awakening and

liberation, teaching, death” must be true.[108]

Previous lives

The legendary Jataka collections depict the Buddha-to-be in a previous

life prostrating before the past Buddha Dipankara, making a resolve to

be a Buddha, and receiving a prediction of future Buddhahood.

Legendary biographies like the Pali Buddhavaṃsa and the Sanskrit

Jātakamālā depict the Buddha’s (referred to as “bodhisattva” before his

awakening) career as spanning hundreds of lifetimes before his last

birth as Gautama. Many stories of these previous lives are depicted in

the Jatakas.[109] The format of a Jataka typically begins by telling a

story in the present which is then explained by a story of someone’s

previous life.[110]

Besides imbuing the pre-Buddhist past with a deep karmic history, the

Jatakas also serve to explain the bodhisattva’s (the Buddha-to-be) path

to Buddhahood.[111] In biographies like the Buddhavaṃsa, this path is

described as long and arduous, taking “four incalculable ages”

(asamkheyyas).[112]

In these legendary biographies, the bodhisattva goes through many

different births (animal and human), is inspired by his meeting of past

Buddhas, and then makes a series of resolves or vows (pranidhana) to

become a Buddha himself. Then he begins to receive predictions by past

Buddhas.[113] One of the most popular of these stories is his meeting

with Dipankara Buddha, who gives the bodhisattva a prediction of future

Buddhahood.[114]

Another theme found in the Pali Jataka Commentary (Jātakaṭṭhakathā) and

the Sanskrit Jātakamālā is how the Buddha-to-be had to practice several

“perfections” (pāramitā) to reach Buddhahood.[115] The Jatakas also

sometimes depict negative actions done in previous lives by the

bodhisattva, which explain difficulties he experienced in his final life

as Gautama.[116]

Biography

Birth and early life

Map showing Lumbini and other major Buddhist sites in India. Lumbini

(present-day Nepal), is the birthplace of the Buddha,[50][note 1] and is

a holy place also for many non-Buddhists.[note 10]

The Lumbini pillar contains an inscription stating that this is the

Buddha’s birthplace

The Buddhist tradition regards Lumbini, in present-day Nepal to be the

birthplace of the Buddha.[117][note 1] He grew up in Kapilavastu.[note

1] The exact site of ancient Kapilavastu is unknown.[118] It may have

been either Piprahwa, Uttar Pradesh, in present-day India,[60] or

Tilaurakot, in present-day Nepal.[64] Both places belonged to the Sakya

territory, and are located only 15 miles (24 km) apart.[64]

The earliest Buddhist sources state that the Buddha was born to an

aristocratic Kshatriya (Pali: khattiya) family called Gotama (Sanskrit:

Gautama), who were part of the Shakyas, a tribe of rice-farmers living

near the modern border of India and Nepal.[119][58][120][note 11] the

son of Śuddhodana, “an elected chief of the Shakya clan”,[7] whose

capital was Kapilavastu, and who were later annexed by the growing

Kingdom of Kosala during the Buddha’s lifetime. Gautama was the family

name. According to later biographies such as the Mahavastu and the

Lalitavistara, his mother, Maya (Māyādevī), Suddhodana’s wife, was a

Koliyan princess. Legend has it that, on the night Siddhartha was

conceived, Queen Maya dreamt that a white elephant with six white tusks

entered her right side,[122][123] and ten months later[124] Siddhartha

was born. As was the Shakya tradition, when his mother Queen Maya became

pregnant, she left Kapilavastu for her father’s kingdom to give birth.

However, her son is said to have been born on the way, at Lumbini, in a

garden beneath a sal tree.

The early Buddhist texts contain very little information about the birth

and youth of Gotama Buddha.[125][126] Later biographies developed a

dramatic narrative about the life of the young Gotama as a prince and

his existential troubles.[127] They also depict his father Śuddhodana as

a hereditary monarch of the Suryavansha (Solar dynasty) of Ikṣvāku

(Pāli: Okkāka). This is unlikely however, as many scholars think that

Śuddhodana was merely a Shakya aristocrat (khattiya), and that the

Shakya republic was not a hereditary monarchy.[128][129][130] Indeed,

the more egalitarian gana-sangha form of government, as a political

alternative to Indian monarchies, may have influenced the development of

the śramanic Jain and Buddhist sanghas, where monarchies tended toward

Vedic Brahmanism.[131]

The day of the Buddha’s birth is widely celebrated in Theravada

countries as Vesak.[132] Buddha’s Birthday is called Buddha Purnima in

Nepal, Bangladesh, and India as he is believed to have been born on a

full moon day.

According to later biographical legends, during the birth celebrations,

the hermit seer Asita journeyed from his mountain abode, analyzed the

child for the “32 marks of a great man” and then announced that he would

either become a great king (chakravartin) or a great religious

leader.[133][134] Suddhodana held a naming ceremony on the fifth day and

invited eight Brahmin scholars to read the future. All gave similar

predictions.[133] Kondañña, the youngest, and later to be the first

arhat other than the Buddha, was reputed to be the only one who

unequivocally predicted that Siddhartha would become a Buddha.[135]

Early texts suggest that Gautama was not familiar with the dominant

religious teachings of his time until he left on his religious quest,

which is said to have been motivated by existential concern for the

human condition.[136] According to the early Buddhist Texts of several

schools, and numerous post-canonical accounts, Gotama had a wife,

Yasodhara, and a son, named Rāhula.[137] Besides this, the Buddha in the

early texts reports that “‘I lived a spoilt, a very spoilt life, monks

(in my parents’ home).”[138]

The legendary biographies like the Lalitavistara also tell stories of

young Gotama’s great martial skill, which was put to the test in various

contests against other Shakyan youths.[139]

Renunciation

See also: Great Renunciation

The “Great Departure” of Siddhartha Gautama, surrounded by a halo, he is

accompanied by numerous guards and devata who have come to pay homage;

Gandhara, Kushan period

While the earliest sources merely depict Gotama seeking a higher

spiritual goal and becoming an ascetic or sramana after being

disillusioned with lay life, the later legendary biographies tell a more

elaborate dramatic story about how he became a mendicant.[127][140]

The earliest accounts of the Buddha’s spiritual quest is found in texts

such as the Pali Ariyapariyesanā-sutta (”The discourse on the noble

quest,” MN 26) and its Chinese parallel at MĀ 204.[141] These texts

report that what led to Gautama’s renunciation was the thought that his

life was subject to old age, disease and death and that there might be

something better (i.e. liberation, nirvana).[142] The early texts also

depict the Buddha’s explanation for becoming a sramana as follows: “The

household life, this place of impurity, is narrow - the samana life is

the free open air. It is not easy for a householder to lead the

perfected, utterly pure and perfect holy life.”[143] MN 26, MĀ 204, the

Dharmaguptaka Vinaya and the Mahāvastu all agree that his mother and

father opposed his decision and “wept with tearful faces” when he

decided to leave.[144][145]

Prince Siddhartha shaves his hair and becomes a sramana. Borobudur, 8th

century

Legendary biographies also tell the story of how Gautama left his palace

to see the outside world for the first time and how he was shocked by

his encounter with human suffering.[146][147] The legendary biographies

depict Gautama’s father as shielding him from religious teachings and

from knowledge of human suffering, so that he would become a great king

instead of a great religious leader.[148] In the Nidanakatha (5th

century CE), Gautama is said to have seen an old man. When his

charioteer Chandaka explained to him that all people grew old, the

prince went on further trips beyond the palace. On these he encountered a

diseased man, a decaying corpse, and an ascetic that inspired

him.[149][150][151] This story of the “four sights” seems to be adapted

from an earlier account in the Digha Nikaya (DN 14.2) which instead

depicts the young life of a previous Buddha, Vipassi.[151]

The legendary biographies depict Gautama’s departure from his palace as

follows. Shortly after seeing the four sights, Gautama woke up at night

and saw his female servants lying in unattractive, corpse-like poses,

which shocked him.[152] Therefore, he discovered what he would later

understand more deeply during his enlightenment: suffering and the end

of suffering.[153] Moved by all the things he had experienced, he

decided to leave the palace in the middle of the night against the will

of his father, to live the life of a wandering ascetic.[149] Accompanied

by Chandaka and riding his horse Kanthaka, Gautama leaves the palace,

leaving behind his son Rahula and Yaśodhara.[154] He traveled to the

river Anomiya, and cut off his hair. Leaving his servant and horse

behind, he journeyed into the woods and changed into monk’s robes

there,[155] though in some other versions of the story, he received the

robes from a Brahma deity at Anomiya.[156]

According to the legendary biographies, when the ascetic Gautama first

went to Rajagaha (present-day Rajgir) to beg for alms in the streets,

King Bimbisara of Magadha learned of his quest, and offered him a share

of his kingdom. Gautama rejected the offer but promised to visit his

kingdom first, upon attaining enlightenment.[157][158]

Ascetic life and Awakening

Ascetic life and Awakening

See also: Enlightenment in Buddhism

Main articles: Moksha and Nirvana (Buddhism)

All sources agree that the ascetic Gautama practised under two teachers

of yogic meditation.[159][160][161] According to MN 26 and its Chinese

parallel at MĀ 204, after having mastered the teaching of Ārāḍa Kālāma

(Pali: Alara Kalama), who taught a meditation attainment called “the

sphere of nothingness”, he was asked by Ārāḍa to become an equal leader

of their spiritual community.[162][163] However, Gautama felt

unsatisfied by the practice because it “does not lead to revulsion, to

dispassion, to cessation, to calm, to knowledge, to awakening, to

Nibbana”, and moved on to become a student of Udraka Rāmaputra (Pali:

Udaka Ramaputta).[164][165] With him, he achieved high levels of

meditative consciousness (called “The Sphere of Neither Perception nor

Non-Perception”) and was again asked to join his teacher. But, once

more, he was not satisfied for the same reasons as before, and moved

on.[166]

Majjhima Nikaya 4 also mentions that Gautama lived in “remote jungle

thickets” during his years of spiritual striving and had to overcome the

fear that he felt while living in the forests.[167]

The gilded “Emaciated Buddha statue” in an Ubosoth in Bangkok

representing the stage of his asceticism

After leaving his meditation teachers, Gotama then practiced ascetic

techniques.[168] An account of these practices can be seen in the

Mahāsaccaka-sutta (MN 36) and its various parallels (which according to

Analayo include some Sanskrit fragments, an individual Chinese

translation, a sutra of the Ekottarika-āgama as well as sections of the

Lalitavistara and the Mahāvastu).[169] The ascetic techniques described

in the early texts include very minimal food intake, different forms of

breath control, and forceful mind control. The texts report that he

became so emaciated that his bones became visible through his skin.[170]

According to other early Buddhist texts,[171] after realising that

meditative dhyana was the right path to awakening, Gautama discovered

“the Middle Way”—a path of moderation away from the extremes of

self-indulgence and self-mortification, or the Noble Eightfold

Path.[171] His break with asceticism is said to have led his five

companions to abandon him, since they believed that he had abandoned his

search and become undisciplined. One popular story tells of how he

accepted milk and rice pudding from a village girl named Sujata.[172]

The Mahabodhi Tree at the Sri Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya

Following his decision to stop extreme ascetic practices, MĀ 204 and

other parallel early texts report that Gautama sat down to meditate with

the determination not to get up until full awakening (sammā-sambodhi)

had been reached.[173] This event was said to have occurred under a

pipal tree—known as “the Bodhi tree”—in Bodh Gaya, Bihar.[174]

Likewise, the Mahāsaccaka-sutta and most of its parallels agree that

after taking asceticism to its extremes, the Buddha realized that this

had not helped him reach awakening. At this point, he remembered a

previous meditative experience he had as a child sitting under a tree

while his father worked.[175] This memory leads him to understand that

dhyana (meditation) is the path to awakening, and the texts then depict

the Buddha achieving all four dhyanas, followed by the “three higher

knowledges” (tevijja) culminating in awakening.[176]

Miracle of the Buddha walking on the River Nairañjanā. The Buddha is not

visible (aniconism), only represented by a path on the water, and his

empty throne bottom right.[177] Sanchi.

Gautama thus became known as the Buddha or “Awakened One”. The title

indicates that unlike most people who are “asleep”, a Buddha is

understood as having “woken up” to the true nature of reality and sees

the world ‘as it is’ (yatha-bhutam).[13] A Buddha has achieved

liberation (vimutti), also called Nirvana, which is seen as the

extinguishing of the “fires” of desire, hatred, and ignorance, that keep

the cycle of suffering and rebirth going.[178] According to various

early texts like the Mahāsaccaka-sutta, and the Samaññaphala Sutta, a

Buddha has achieved three higher knowledges: Remembering one’s former

abodes (i.e. past lives), the “Divine eye” (dibba-cakkhu), which allows

the knowing of others’ karmic destinations and the “extinction of mental

intoxicants” (āsavakkhaya).[170][179]

According to some texts from the Pali canon, at the time of his

awakening he realised complete insight into the Four Noble Truths,

thereby attaining liberation from samsara, the endless cycle of

rebirth.[180][181][182] [note 12]

As reported by various texts from the Pali Canon, the Buddha sat for

seven days under the bodhi tree “feeling the bliss of deliverance.”[183]

The Pali texts also report that he continued to meditate and

contemplated various aspects of the Dharma while living by the River

Nairañjanā, such as Dependent Origination, the Five Spiritual Faculties

and Suffering.[184]

The legendary biographies like the Mahavastu and the Lalitavistara

depict an attempt by Mara, the Lord of the desire realm, to prevent the

Buddha’s nirvana. He does so by sending his daughters to seduce the

Buddha, by asserting his superiority and by assaulting him with armies

of monsters.[185] However the Buddha is unfazed and calls on the earth

(or in some versions of the legend, the earth goddess) as witness to his

superiority by touching the ground before entering meditation.[186]

Other miracles and magical events are also depicted.

First sermon and formation of the saṅgha

Dhamek Stupa in Sarnath, India, site of the first teaching of the Buddha

in which he taught the Four Noble Truths to his first five disciples

According to MN 26, immediately after his awakening, the Buddha

hesitated on whether or not he should teach the Dharma to others. He was

concerned that humans were overpowered by ignorance, greed, and hatred

that it would be difficult for them to recognise the path, which is

“subtle, deep and hard to grasp.” The Nyingma scholar Khenchen Palden

Sherab Rinpoche states the Buddha spent forty-nine days in meditation to

ascertain whether or not to begin teaching.[187] However, the god

Brahmā Sahampati convinced him, arguing that at least some “with little

dust in their eyes” will understand it. The Buddha relented and agreed

to teach. According to Analayo, the Chinese parallel to MN 26, MĀ 204,

does not contain this story, but this event does appear in other

parallel texts, such as in an Ekottarika-āgama discourse, in the

Catusparisat-sūtra, and in the Lalitavistara.[173]

According to MN 26 and MĀ 204, after deciding to teach, the Buddha

initially intended to visit his former teachers, Alara Kalama and Udaka

Ramaputta, to teach them his insights, but they had already died, so he

decided to visit his five former companions.[188] MN 26 and MĀ 204 both

report that on his way to Vārānasī (Benares), he met another wanderer,

called Ājīvika Upaka in MN 26. The Buddha proclaimed that he had

achieved full awakening, but Upaka was not convinced and “took a

different path”.[189]

MN 26 and MĀ 204 continue with the Buddha reaching the Deer Park

(Sarnath) (Mrigadāva, also called Rishipatana, “site where the ashes of

the ascetics fell”)[190] near Vārānasī , where he met the group of five

ascetics and was able to convince them that he had indeed reached full

awakening.[191] According to MĀ 204 (but not MN 26), as well as the

Theravāda Vinaya, an Ekottarika-āgama text, the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya,

the Mahīśāsaka Vinaya, and the Mahāvastu, the Buddha then taught them

the “first sermon”, also known as the “Benares sermon”,[190] i.e. the

teaching of “the noble eightfold path as the middle path aloof from the

two extremes of sensual indulgence and self-mortification.”[191] The

Pali text reports that after the first sermon, the ascetic Koṇḍañña

(Kaundinya) became the first arahant (liberated being) and the first

Buddhist bhikkhu or monastic.[192] The Buddha then continued to teach

the other ascetics and they formed the first saṅgha: the company of

Buddhist monks.

Various sources such as the Mahāvastu, the Mahākhandhaka of the

Theravāda Vinaya and the Catusparisat-sūtra also mention that the Buddha

taught them his second discourse, about the characteristic of

“not-self” (Anātmalakṣaṇa Sūtra), at this time[193] or five days

later.[190] After hearing this second sermon the four remaining ascetics

also reached the status of arahant.[190]

The chief disciples of the Buddha, Mogallana (chief in psychic power)

and Sariputta (chief in wisdom).

The first vassana was spent at Varanasi when the sangha was formed.

According to the Pali texts, shortly after the formation of the sangha,

the Buddha traveled to Rajagaha, capital of Magadha, and met with King

Bimbisara, who gifted a bamboo grove park to the sangha.[203]

The Buddha’s sangha continued to grow during his initial travels in

north India. The early texts tell the story of how the Buddha’s chief

disciples, Sāriputta and Mahāmoggallāna, who were both students of the

skeptic sramana Sañjaya Belaṭṭhiputta, were converted by

Assaji.[204][205] They also tell of how the Buddha’s son, Rahula, joined

his father as a bhikkhu when the Buddha visited his old home,

Kapilavastu.[206] Over time, other Shakyans joined the order as

bhikkhus, such as Buddha’s cousin Ananda, Anuruddha, Upali the barber,

the Buddha’s half-brother Nanda and Devadatta.[207][208] Meanwhile, the

Buddha’s father Suddhodana heard his son’s teaching, converted to

Buddhism and became a

stream-enterer.https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Buddha_mit_Mogallana_und_Sariputta.JPGhttps://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Buddha_mit_Mogallana_und_Sariputta.JPG

The remains of a section of Jetavana Monastery, just outside of ancient

Savatthi, in Uttar Pradesh.

The early texts also mention an important lay disciple, the merchant

Anāthapiṇḍika, who became a strong lay supporter of the Buddha early on.

He is said to have gifted Jeta’s grove (Jetavana) to the sangha at

great expense (the Theravada Vinaya speaks of thousands of gold

coins).[209][210]

Formation of the bhikkhunī order

Mahāprajāpatī, the first bhikkuni and Buddha’s stepmother, ordains

The formation of a parallel order of female monastics (bhikkhunī) was

another important part of the growth of the Buddha’s community. As noted

by Analayo’s comparative study of this topic, there are various

versions of this event depicted in the different early Buddhist

texts.[note 13]

According to all the major versions surveyed by Analayo, Mahāprajāpatī

Gautamī, Buddha’s step-mother, is initially turned down by the Buddha

after requesting ordination for her and some other women. Mahāprajāpatī

and her followers then shave their hair, don robes and begin following

the Buddha on his travels. The Buddha is eventually convinced by Ānanda

to grant ordination to Mahāprajāpatī on her acceptance of eight

conditions called gurudharmas which focus on the relationship between

the new order of nuns and the monks.[212]

According to Analayo, the only argument common to all the versions that

Ananda uses to convince the Buddha is that women have the same ability

to reach all stages of awakening.[213] Analayo also notes that some

modern scholars have questioned the authenticity of the eight

gurudharmas in their present form due to various inconsistencies. He

holds that the historicity of the current lists of eight is doubtful,

but that they may have been based on earlier injunctions by the

Buddha.[214][215] Analayo also notes that various passages indicate that

the reason for the Buddha’s hesitation to ordain women was the danger

that the life of a wandering sramana posed for women that were not under

the protection of their male family members (such as dangers of sexual

assault and abduction). Due to this, the gurudharma injunctions may have

been a way to place “the newly founded order of nuns in a relationship

to its male counterparts that resembles as much as possible the

protection a laywoman could expect from her male relatives.”[216]

Later years

Procession of King Prasenajit of Kosala leaving Sravasti to meet the

Buddha. Sanchi[217]

Ajatasattu worships the Buddha, relief from the Bharhut Stupa at the

Indian Museum, Kolkata

According to J.S. Strong, after the first 20 years of his teaching

career, the Buddha seems to have slowly settled in Sravasti, the capital

of the Kingdom of Kosala, spending most of his later years in this

city.[210]

As the sangha grew in size, the need for a standardized set of monastic

rules arose and the Buddha seems to have developed a set of regulations

for the sangha. These are preserved in various texts called “Pratimoksa”

which were recited by the community every fortnight. The Pratimoksa

includes general ethical precepts, as well as rules regarding the

essentials of monastic life, such as bowls and robes.[218]

In his later years, the Buddha’s fame grew and he was invited to

important royal events, such as the inauguration of the new council hall

of the Shakyans (as seen in MN 53) and the inauguration of a new palace

by Prince Bodhi (as depicted in MN 85).[219] The early texts also speak

of how during the Buddha’s old age, the kingdom of Magadha was usurped

by a new king, Ajatasattu, who overthrew his father Bimbisara. According

to the Samaññaphala Sutta, the new king spoke with different ascetic

teachers and eventually took refuge in the Buddha.[220] However, Jain

sources also claim his allegiance, and it is likely he supported various

religious groups, not just the Buddha’s sangha exclusively.[221]

As the Buddha continued to travel and teach, he also came into contact

with members of other śrāmana sects. There is evidence from the early

texts that the Buddha encountered some of these figures and critiqued

their doctrines. The Samaññaphala Sutta identifies six such sects.[222]

The early texts also depict the elderly Buddha as suffering from back

pain. Several texts depict him delegating teachings to his chief

disciples since his body now needed more rest.[223] However, the Buddha

continued teaching well into his old age.

One of the most troubling events during the Buddha’s old age was

Devadatta’s schism. Early sources speak of how the Buddha’s cousin,

Devadatta, attempted to take over leadership of the order and then left

the sangha with several Buddhist monks and formed a rival sect. This

sect is said to have also been supported by King Ajatasattu.[224][225]

The Pali texts also depict Devadatta as plotting to kill the Buddha, but

these plans all fail.[226] They also depict the Buddha as sending his

two chief disciples (Sariputta and Moggallana) to this schismatic

community in order to convince the monks who left with Devadatta to

return.[227]

All the major early Buddhist Vinaya texts depict Devadatta as a divisive

figure who attempted to split the Buddhist community, but they disagree

on what issues he disagreed with the Buddha on. The Sthavira texts

generally focus on “five points” which are seen as excessive ascetic

practices, while the Mahāsaṅghika Vinaya speaks of a more comprehensive

disagreement, which has Devadatta alter the discourses as well as

monastic discipline.[228]

At around the same time of Devadatta’s schism, there was also war

between Ajatasattu’s Kingdom of Magadha, and Kosala, led by an elderly

king Pasenadi.[229] Ajatasattu seems to have been victorious, a turn of

events the Buddha is reported to have regretted.

Last days and parinirvana

Metal relief

This East Javanese relief depicts the Buddha in his final days, and

Ānanda, his chief attendant.

The main narrative of the Buddha’s last days, death and the events

following his death is contained in the Mahaparinibbana Sutta (DN 16)

and its various parallels in Sanskrit, Chinese, and Tibetan.[231]

According to Analayo, these include the Chinese Dirgha Agama 2,

“Sanskrit fragments of the Mahaparinirvanasutra”, and “three discourses

preserved as individual translations in Chinese”.[232]

The Mahaparinibbana sutta depicts the Buddha’s last year as a time of

war. It begins with Ajatasattu’s decision to make war on the Vajjian

federation, leading him to send a minister to ask the Buddha for

advice.[233] The Buddha responds by saying that the Vajjians can be

expected to prosper as long as they do seven things, and he then applies

these seven principles to the Buddhist Sangha, showing that he is

concerned about its future welfare. The Buddha says that the Sangha will

prosper as long as they “hold regular and frequent assemblies, meet in

harmony, do not change the rules of training, honor their superiors who

were ordained before them, do not fall prey to worldly desires, remain

devoted to forest hermitages, and preserve their personal mindfulness.”

He then gives further lists of important virtues to be upheld by the

Sangha.[234]

The early texts also depict how the Buddha’s two chief disciples,

Sariputta and Moggallana, died just before the Buddha’s death.[235] The

Mahaparinibbana depicts the Buddha as experiencing illness during the

last months of his life but initially recovering. It also depicts him as

stating that he cannot promote anyone to be his successor. When Ānanda

requested this, the Mahaparinibbana records his response as

follows:[236]

Ananda, why does the Order of monks expect this of me? I have taught the

Dhamma, making no distinction of “inner” and “ outer”: the Tathagata

has no “teacher’s fist” (in which certain truths are held back). If

there is anyone who thinks: “I shall take charge of the Order”, or “the

Order is under my leadership”, such a person would have to make

arrangements about the Order. The Tathagata does not think in such

terms. Why should the Tathagata make arrangements for the Order? I am

now old, worn out . . . I have reached the term of life, I am turning

eighty years of age. Just as an old cart is made to go by being held

together with straps, so the Tathagata’s body is kept going by being

bandaged up . . . Therefore, Ananda, you should live as islands unto

yourselves, being your own refuge, seeking no other refuge; with the

Dhamma as an island, with the Dhamma as your refuge, seeking no other

refuge. . . Those monks who in my time or afterwards live thus, seeking

an island and a refuge in themselves and in the Dhamma and nowhere else,

these zealous ones are truly my monks and will overcome the darkness

(of rebirth).

Mahaparinibbana scene, from the Ajanta caves

After traveling and teaching some more, the Buddha ate his last meal,

which he had received as an offering from a blacksmith named Cunda.

Falling violently ill, Buddha instructed his attendant Ānanda to

convince Cunda that the meal eaten at his place had nothing to do with

his death and that his meal would be a source of the greatest merit as

it provided the last meal for a Buddha.[237] Bhikkhu and von Hinüber

argue that the Buddha died of mesenteric infarction, a symptom of old

age, rather than food poisoning.[238][239]

The precise contents of the Buddha’s final meal are not clear, due to

variant scriptural traditions and ambiguity over the translation of

certain significant terms. The Theravada tradition generally believes

that the Buddha was offered some kind of pork, while the Mahayana

tradition believes that the Buddha consumed some sort of truffle or

other mushroom. These may reflect the different traditional views on

Buddhist vegetarianism and the precepts for monks and nuns.[240] Modern

scholars also disagree on this topic, arguing both for pig’s flesh or

some kind of plant or mushroom that pigs like to eat.[note 14] Whatever

the case, none of the sources which mention the last meal attribute the

Buddha’s sickness to the meal itself.[241]

As per the Mahaparinibbana sutta, after the meal with Cunda, the Buddha

and his companions continued traveling until he was too weak to continue

and had to stop at Kushinagar, where Ānanda had a resting place

prepared in a grove of Sala trees.[242][243] After announcing to the

sangha at large that he would soon be passing away to final Nirvana, the

Buddha ordained one last novice into the order personally, his name was

Subhadda.[242] He then repeated his final instructions to the sangha,

which was that the Dhamma and Vinaya was to be their teacher after his

death. Then he asked if anyone had any doubts about the teaching, but

nobody did.[244] The Buddha’s final words are reported to have been:

“All saṅkhāras decay. Strive for the goal with diligence (appamāda)”

(Pali: ‘vayadhammā saṅkhārā appamādena sampādethā’).[245][246]

He then entered his final meditation and died, reaching what is known as

parinirvana (final nirvana, the end of rebirth and suffering achieved

after the death of the body). The Mahaparinibbana reports that in his

final meditation he entered the four dhyanas consecutively, then the

four immaterial attainments and finally the meditative dwelling known as

nirodha-samāpatti, before returning to the fourth dhyana right at the

moment of death.[247][243]

Piprahwa vase with relics of the Buddha. The inscription reads:

…salilanidhane Budhasa Bhagavate… (Brahmi script:

…𑀲𑀮𑀺𑀮𑀦𑀺𑀥𑀸𑀦𑁂 𑀩𑀼𑀥𑀲 𑀪𑀕𑀯𑀢𑁂…]) “Relics of the Buddha

Lord”.

Posthumous events

See also: Śarīra and Relics associated with Buddha

According to the Mahaparinibbana sutta, the Mallians of Kushinagar spent

the days following the Buddha’s death honoring his body with flowers,

music and scents.[248] The sangha waited until the eminent elder

Mahākassapa arrived to pay his respects before cremating the body.[249]

The Buddha’s body was then cremated and the remains, including his

bones, were kept as relics and they were distributed among various north

Indian kingdoms like Magadha, Shakya and Koliya.[250] These relics were

placed in monuments or mounds called stupas, a common funerary practice

at the time. Centuries later they would be exhumed and enshrined by

Ashoka into many new stupas around the Mauryan realm.[251][252] Many

supernatural legends surround the history of alleged relics as they

accompanied the spread of Buddhism and gave legitimacy to rulers.

According to various Buddhist sources, the First Buddhist Council was

held shortly after the Buddha’s death to collect, recite and memorize

the teachings. Mahākassapa was chosen by the sangha to be the chairman

of the council. However, the historicity of the traditional accounts of

the first council is disputed by modern scholars.[253]

Teachings

Main article: Buddhist philosophy § The Buddha and early Buddhism

Tracing the oldest teachings

One method to obtain information on the oldest core of Buddhism is to

compare the oldest versions of the Pali Canon and other texts, such as

the surviving portions of Sarvastivada, Mulasarvastivada, Mahisasaka,

Dharmaguptaka,[254][255] and the Chinese Agamas.[256][257] The

reliability of these sources, and the possibility of drawing out a core

of oldest teachings, is a matter of dispute.[258][259][260][261]

According to Tilmann Vetter, inconsistencies remain, and other methods

must be applied to resolve those inconsistencies.[254][note 15]

According to Lambert Schmithausen, there are three positions held by

modern scholars of Buddhism:[264]

“Stress on the fundamental homogeneity and substantial authenticity of

at least a considerable part of the Nikayic materials.”[note 16]

“Scepticism with regard to the possibility of retrieving the doctrine of

earliest Buddhism.”[note 17]

“Cautious optimism in this respect.”[note 18]

Regarding their attribution to the historical Buddha Gautama

“Sakyamuni”, scholars such as Richard Gombrich, Akira Hirakawa,

Alexander Wynne and A.K. Warder hold that these Early Buddhist Texts

contain material that could possibly be traced to this

figure.[261][269][142]

Influences

The Bodhisattva meets with Alara Kalama, Borobudur relief.

According to scholars of Indology such as Richard Gombrich, the Buddha’s

teachings on Karma and Rebirth are a development of pre-Buddhist themes

that can be found in Jain and Brahmanical sources, like the

Brihadaranyaka Upanishad.[270] Likewise, samsara, the idea that we are

trapped in cycle of rebirth and that we should seek liberation from this

through non-harming (ahimsa) and spiritual practices, pre-dates the

Buddha and was likely taught in early Jainism.[271]

In various texts, the Buddha is depicted as having studied under two

named teachers, Āḷāra Kālāma and Uddaka Rāmaputta. According to

Alexander Wynne, these were yogis who taught doctrines and practices

similar to those in the Upanishads.[272]

The Buddha’s tribe of origin, the Shakyas, also seem to have had

non-Vedic religious practices which influenced Buddhism, such as the

veneration of trees and sacred groves, and the worship of tree spirits

(yakkhas) and serpent beings (nagas). They also seem to have built

burial mounds called stupas.[67]

Tree veneration remains important in Buddhism today, particularly in the

practice of venerating Bodhi trees. Likewise, yakkas and nagas have

remained important figures in Buddhist religious practices and

mythology.[67]

In the Early Buddhist Texts, the Buddha also references Brahmanical

devices. For example, in Samyutta Nikaya 111, Majjhima Nikaya 92 and

Vinaya i 246 of the Pali Canon, the Buddha praises the Agnihotra as the

foremost sacrifice and the Gayatri mantra as the foremost meter.[note

19]

The Buddhist teaching of the three marks of existence[note 20] may also

reflect Upanishadic or other influences according to K.R. Norman.[274]

According to Johannes Bronkhorst, the “meditation without breath and

reduced intake of food” which the Buddha practiced before his awakening

are forms of asceticism which are similar to Jain practices.[275]

The Buddhist practice called Brahma-vihara may have also originated from

a Brahmanic term;[276] but its usage may have been common in the

sramana traditions.[258]

Teachings preserved in the Early Buddhist Texts

Teachings preserved in the Early Buddhist Texts

Gandharan Buddhist birchbark scroll fragments

Main article: Early Buddhist Texts

The Early Buddhist Texts present many teachings and practices which may

have been taught by the historical Buddha. These include basic doctrines

such as Dependent Origination, the Middle Way, the Five Aggregates, the

Three unwholesome roots, the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path.

According to N. Ross Reat, all of these doctrines are shared by the

Theravada Pali texts and the Mahasamghika school’s Śālistamba

Sūtra.[277]

A recent study by Bhikkhu Analayo concludes that the Theravada Majjhima

Nikaya and Sarvastivada Madhyama Agama contain mostly the same major

doctrines.[278] Likewise, Richard Salomon has written that the doctrines

found in the Gandharan Manuscripts are “consistent with non-Mahayana

Buddhism, which survives today in the Theravada school of Sri Lanka and

Southeast Asia, but which in ancient times was represented by eighteen

separate schools.”[279]

These basic teachings such as the Four Noble Truths tend to be widely

accepted as basic doctrines in all major schools of Buddhism, as seen in

ecumenical documents such as the Basic points unifying Theravāda and

Mahāyāna.

Critique of Brahmanism

Buddha meets a Brahmin, at the Indian Museum, Kolkata

In the early Buddhist texts, the Buddha critiques the Brahmanical

religion and social system on certain key points.

The Brahmin caste held that the Vedas were eternal revealed (sruti)

texts. The Buddha, on the other hand, did not accept that these texts

had any divine authority or value.[280]

The Buddha also did not see the Brahmanical rites and practices as

useful for spiritual advancement. For example, in the Udāna, the Buddha

points out that ritual bathing does not lead to purity, only “truth and

morality” lead to purity.[note 21] He especially critiqued animal

sacrifice as taught in Vedas.[280] The Buddha contrasted his teachings,

which were taught openly to all people, with that of the Brahmins’, who

kept their mantras secret.[note 22]

He also critiqued numerous other Brahmanical practices, such astrology,

divination, fortune-telling, and so on (as seen in the Tevijja sutta and

the Kutadanta sutta).[282]

The Buddha also attacked the Brahmins’ claims of superior birth and the

idea that different castes and bloodlines were inherently pure or

impure, noble or ignoble.[280]

In the Vasettha sutta the Buddha argues that the main difference among

humans is not birth but their actions and occupations.[283] According to

the Buddha, one is a “Brahmin” (i.e. divine, like Brahma) only to the

extent that one has cultivated virtue.[note 23] Because of this the

early texts report that he proclaimed: “Not by birth one is a Brahman,

not by birth one is a non-Brahman; - by moral action one is a

Brahman”[280]

The Aggañña Sutta explains all classes or varnas can be good or bad and

gives a sociological explanation for how they arose, against the

Brahmanical idea that they are divinely ordained.[284] According to

Kancha Ilaiah, the Buddha posed the first contract theory of

society.[285] The Buddha’s teaching then is a single universal moral

law, one Dharma valid for everybody, which is opposed to the Brahmanic

ethic founded on “one’s own duty” (svadharma) which depends on

caste.[280] Because of this, all castes including untouchables were

welcome in the Buddhist order and when someone joined, they renounced

all caste affiliation.[286][287]

Analysis of existence

The early Buddhist texts present the Buddha’s worldview as focused on

understanding the nature of dukkha, which is seen as the fundamental

problem of life.[288] Dukkha refers to all kinds of suffering, unease,

frustration, and dissatisfaction that sentient beings

experience.[289][290] At the core of the Buddha’s analysis of dukkha is

the fact that everything we experience is impermanent, unstable and thus

unreliable.[291]

A common presentation of the core structure of Buddha’s teaching found

in the early texts is that of the Four Noble Truths.[292] This teaching

is most famously presented in the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta (”The

discourse on the turning of the Dharma wheel”) and its many

parallels.[293] The basic outline of the four truths is as

follows:[292][289]

There is dukkha.

There are causes and conditions for the arising of dukkha. Various

conditions are outlined in the early texts, such as craving (taṇhā), but

the three most basic ones are greed, aversion and delusion.[294]

If the conditions for dukkha cease, dukkha also ceases. This is

“Nirvana” (literally ‘blowing out’ or ‘extinguishing’).[295]

There is path to follow that leads to Nirvana.

According to Bhikkhu Analayo, the four truths schema appears to be based

“on an analogy with Indian medical diagnosis” (with the form: “disease,

pathogen, health, cure”) and this comparison is “explicitly made in

several early Buddhist texts”.[293]

In another Pali sutta, the Buddha outlines how “eight worldly

conditions”, “keep the world turning around…Gain and loss, fame and

disrepute, praise and blame, pleasure and pain.” He then explains how

the difference between a noble (arya) person and an uninstructed

worldling is that a noble person reflects on and understands the

impermanence of these conditions.[296]

The Buddha’s analysis of existence includes an understanding that karma

and rebirth are part of life. According to the Buddha, the constant

cycle of dying and being reborn (i.e. saṃsāra) according to one’s karma

is just dukkha and the ultimate spiritual goal should be liberation from

this cycle.[297] According to the Pali suttas, the Buddha stated that

“this saṃsāra is without discoverable beginning. A first point is not

discerned of beings roaming and wandering on hindered by ignorance and

fettered by craving.”[298]

The Buddha’s teaching of karma differed to that of the Jains and

Brahmins, in that on his view, karma is primarily mental intention (as

opposed to mainly physical action or ritual acts).[289] The Buddha is

reported to have said “By karma I mean intention.”[299] Richard Gombrich

summarizes the Buddha’s view of karma as follows: “all thoughts, words,

and deeds derive their moral value, positive or negative, from the

intention behind them.”[300]

For the Buddha, our karmic acts also affected the rebirth process in a

positive or negative way. This was seen as an impersonal natural law

similar to how certain seeds produce certain plants and fruits (in fact,

the result of a karmic act was called its “fruit” by the Buddha).[301]

However, it is important to note that the Buddha did not hold that

everything that happens is the result of karma alone. In fact when the

Buddha was asked to state the causes of pain and pleasure he listed

various physical and environmental causes alongside karma.[302]

Dependent Origination

Schist Buddha statue with the famed Ye Dharma Hetu dhāraṇī around the

head, which was used as a common summary of Dependent Origination. It

states: “Of those experiences that arise from a cause, The Tathāgata has

said: ‘this is their cause, And this is their cessation’: This is what

the Great Śramaṇa teaches.”

In the early texts, the process of the arising of dukkha is most

thoroughly explained by the Buddha through the teaching of Dependent

Origination.[289] At its most basic level, Dependent Origination is an

empirical teaching on the nature of phenomena which says that nothing is

experienced independently of its conditions.[303]

The most basic formulation of Dependent Origination is given in the

early texts as: ‘It being thus, this comes about’ (Pali: evam sati idam

hoti).[304] This can be taken to mean that certain phenomena only arise

when there are other phenomena present (example: when there is craving,

suffering arises), and so, one can say that their arising is “dependent”

on other phenomena. In other words, nothing in experience exists

without a cause.[304]

In numerous early texts, this basic principle is expanded with a list of

phenomena that are said to be conditionally dependent.[305][note 24]

These phenomena are supposed to provide an analysis of the cycle of

dukkha as experienced by sentient beings. The philosopher Mark Siderits

has outlined the basic idea of the Buddha’s teaching of Dependent

Origination of dukkha as follows:

given the existence of a fully functioning assemblage of psycho-physical

elements (the parts that make up a sentient being), ignorance

concerning the three characteristics of sentient existence—suffering,

impermanence and non-self—will lead, in the course of normal

interactions with the environment, to appropriation (the identification

of certain elements as ‘I’ and ‘mine’). This leads in turn to the

formation of attachments, in the form of desire and aversion, and the

strengthening of ignorance concerning the true nature of sentient

existence. These ensure future rebirth, and thus future instances of old

age, disease and death, in a potentially unending cycle.[289]

The Buddha saw his analysis of Dependent Origination as a “Middle Way”

between “eternalism” (sassatavada, the idea that some essence exists

eternally) and “annihilationism” (ucchedavada, the idea that we go

completely out of existence at death).[289][304] This middle way is

basically the view that, conventionally speaking, persons are just a

causal series of impermanent psycho-physical elements.[289]

Metaphysics and personal identity

Closely connected to the idea that experience is dependently originated

is the Buddha’s teaching that there is no independent or permanent self

(Sanskrit: atman, Pali: atta).[303]

Due to this view which (termed anatta), the Buddha’s teaching was

opposed to all soul theories of his time, including the Jain theory of a

“jiva” (”life monad”) and the Brahmanical theories of atman and

purusha. All of these theories held that there was an eternal unchanging

essence to a person which transmigrated from life to

life.[306][307][289]

While Brahminical teachers affirmed atman theories in an attempt to

answer the question of what really exists ultimately, the Buddha saw

this question as not being useful, as illustrated in the parable of the

poisoned arrow.[308]

For the Buddha’s contemporaries, the atman was also seen to be the

unchanging constant which was separate from all changing experiences and

the inner controller in a person.[309] The Buddha instead held that all

things in the world of our experience are transient and that there is

no unchanging part to a person.[310] According to Richard Gombrich, the

Buddha’s position is simply that “everything is process”.[311] However,

this anti-essentialist view still includes an understanding of

continuity through rebirth, it is just the rebirth of a process (karma),

not an essence like the atman.[312]

Perhaps the most important way the Buddha analyzed individual experience

in the early texts was by way of the five ‘aggregates’ or ‘groups’

(khandha) of physical and mental processes.[313][314] The Buddha’s

arguments against an unchanging self rely on these five aggregate

schema, as can be seen in the Pali Anattalakkhaṇa Sutta (and its

parallels in Gandhari and Chinese).[315][316][317]

According to the early texts, the Buddha argued that because we have no

ultimate control over any of the psycho-physical processes that make up a

person, there cannot be an “inner controller” with command over them.

Also, since they are all impermanent, one cannot regard any of the

psycho-physical processes as an unchanging self.[318][289] Even mental

processes such as consciousness and will (cetana) are seen as being