31 08 2012 Friday LESSON 690 FREE ONLINE eNālāndā Research and Practice UNIVERSITY

through

http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org

Tipitaka network … his life, his acts, his words

sabbe satta bhavantu sukhi-tatta

TIPITAKA ![]() மூன்று கூடைகள்— The words of the Buddha புத்தரின் வார்த்தைகள்—Majjhima மத்திம Nikāya

மூன்று கூடைகள்— The words of the Buddha புத்தரின் வார்த்தைகள்—Majjhima மத்திம Nikāya

நடுத்தரமான நீள அளவு திரட்டுகள் -Sabbāsava Sutta எல்லா களங்கங்களின் நெறி முறைக் கட்டளை ஆணை (contd)

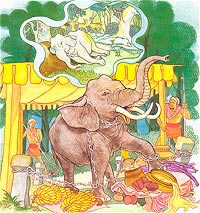

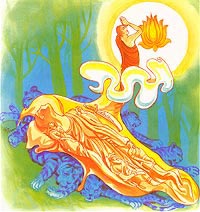

Dhammapada Verse 324 Parijinna Brahmanaputta Vatthu-The Bound Elephant

Hard to check the tusker Dhanapala,

in rut with temple running pungently,

bound, e’en a morsel he’ll not eat

for he recalls the elephant-forest longingly.

Explanation: The elephant, Dhanapala, deep

in rut and uncontrollable did not eat a morsel as he yearned for his native

forest and pined for his parents.

Dhammapada Verse 324

Parijinna Brahmanaputta VatthuDhanapalo nama kunjaro

katukabhedano dunnivarayo

baddho kabalam na bhunjati

sumarati nagavanassa kunjaro.Verse 324: The elephant called Dhanapala, in severe must and uncontrollable,

being in captivity, eats not a morsel, yearning for his native forest (i.e.,

longing to look after his parents).

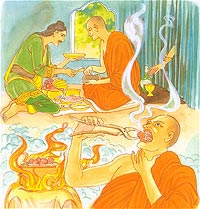

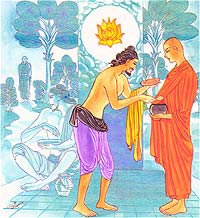

The Story of an Old Brahmin

While residing at the Veluvana monastery, the Buddha uttered Verse (324) of

this book, with reference to an old brahmin.Once, there lived in Savatthi an old brahmin who had eight lakhs in cash. He

had four sons; when each one of the sons got married, he gave one lakh to him.

Thus, he gave away four lakhs. Later, his wife died. His sons came to him and

looked after him very well; in fact, they were very loving and affectionate to

him. In course of time, somehow they coaxed him to give them the remaining four

lakhs. Thus, he was left practically penniless.First, he went to stay with his eldest son. After a few days, the

daughter-in-law said to him, “Did you give any extra hundred or thousand to

your eldest son? Don’t you know the way to the houses of your other sons?”

Hearing this, the old brahmin got very angry and he left the eldest son’s house

for the house of his second son. The same remarks were made by the wife of his

second son and the old man went to the house of his third son and finally to the

house of his fourth and youngest son. The same thing happened in the houses of

all his sons. Thus, the old man became helpless; then, taking a staff and a bowl

he went to the Buddha for protection and advice.At the monastery, the brahmin told the Buddha how his sons had treated him

and asked for his help. Then the Buddha gave him some verses to memorize and

instructed him to recite them wherever there was a large gathering of people.

The gist of the verses is this: “My four foolish sons are like ogres. They

call me ‘father, father’, but the words come only out of their mouths and not

from their hearts. They are deceitful and scheming. Taking the advice of their

wives they have driven me out of their houses. So, now I have got to be begging.

Those sons of mine are of less service to me than this staff of mine.” When

the old brahmin recited these verses, many people in the crowd, hearing him,

went wild with rage at his sons and some even threatened to kill them.At this, the sons became frightened and knelt down at the feet of their

father and asked for pardon. They also promised that starting from that day they

would look after their father properly and would respect, love and honour him.

Then, they took their father to their houses; they also warned their wives to

look after their father well or else they would be beaten to death. Each of the

sons gave a length of cloth and sent every day a food-tray. The brahmin became

healthier than before and soon put on some weight. He realized that he had been

showered with these benefits on account of the Buddha. So, he went to the Buddha

and humbly requested him to accept two food-trays out of the four he was

receiving every day from his sons. Then he instructed his sons to send two

food-trays to the Buddha.One day, the eldest son invited the Buddha to his house for alms-food. After

the meal, the Buddha gave a discourse on the benefits to be gained by looking

after one’s parents. Then he related to them the story of the elephant called

Dhanapala, who looked after his parents. Dhanapala when captured pined for the

parents who were left in the forest.Then the Buddha spoke in verse as follows:

Verse 324: The elephant called Dhanapala, in severe

must and uncontrollable, being in captivity, eats not a morsel,

yearning for his native forest (i. e., longing to look after his

parents).

At the end of the discourse, the old brahmin as well as his four sons and

their wives attained Sotapatti Fruition.

http://www.nps.gov/grca/planyourvisit/cg-sr.htm

Grand Canyon

National Park

Arizona

http://www.tripadvisor.com/Attraction_Review-g31393-d531839-Reviews-Grand_Canyon_Imax_Theater-Tusayan_Arizona.html

Ranked #4 of 4 attractions in Tusayan

Type: Movie Theaters

Owner description:

Explore beyond the rim in this spectacular IMAX adventure film. Shown on

a giant 6-story high screen with digital surround sound. Purchase

park…

more »Update attraction details

Every year, a

staggering five million people flock to Arizona to see the Grand

Canyon’s sweeping views, hike its trails, and hop on a mule for a trip

through the vast canyon.watch video:

http://video.nationalgeographic.com/video/news/culture-places-news/grand-canyon-skywalk-vin/

Culture & Places News:

Grand Canyon Skywalk

Sunrise at Hopi Point as seen from Powell PointA winter sunset at Pima Point.

Sunset from Grand Canyon Village

Mather Point

A view worth hiking to: “Ooh-Ahh Point” on the Kaibab Trail, which begins at Yaki Point

A Yaki Point sunset

Grand Canyon vista from Grandview Point

Sunset and the “Sinking Ship” from Moran Point

The view from Lipan Point

View from Lipan Point

Desert View

The rim from Grandview Trail

A family campsite at Mather Campground located within walking distance of the general store and post office at Market Plaza.

Xanterra Parks Photo

Trailer Village has hook-ups

Restroom and Pay Station

Did You Know?

From Yavapai Point on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon, the drop to

the Colorado River below is 4,600 feet (1,400 m). The elevation at

river level is 2,450 feet (750 m) above sea level. Without the Colorado

River, a perennial river in a desert environment, the Grand Canyon would

not exist.

Kayakers brave rapid waters in Colorado’s Black Canyon of the Gunnison

National Park. As it has for eons, water continues to carve the gorge,

known for its unmatched combination of narrow opening, sheer walls, and

startling depths.

Grand Canyon Photos

Of the five million people that travel to the Grand Canyon

each year, most only view the canyon from a few select viewing points.

Get off the beaten path with the Grand Canyon Photo Gallery.watch video:

http://article.wn.com/view/2012/07/18/Funding_is_sought_to_add_land_to_Yosemite/

4:54

Yosemite Landslide CoverageTLC’s Earth’s Fury landslide coverage, Yosemite National Park…published: 05 May 2009

Yosemite Landslide CoverageTLC’s Earth’s Fury landslide coverage, Yosemite National Park…published: 05 May 2009

30 08 2012 Thursday LESSON 689 FREE ONLINE eNālāndā Research and Practice UNIVERSITY

through

http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org

Tipitaka network … his life, his acts, his words

sabbe satta bhavantu sukhi-tatta

TIPITAKA ![]() மூன்று கூடைகள்— The words of the Buddha புத்தரின் வார்த்தைகள்—Majjhima மத்திம Nikāya

மூன்று கூடைகள்— The words of the Buddha புத்தரின் வார்த்தைகள்—Majjhima மத்திம Nikāya

நடுத்தரமான நீள அளவு திரட்டுகள் -Sabbāsava Sutta எல்லா களங்கங்களின் நெறி முறைக் கட்டளை ஆணை (contd)

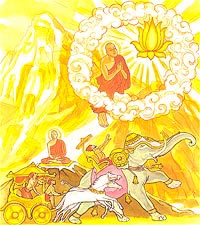

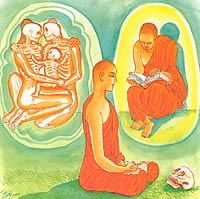

Dhammapada Verse 323 Hatthacariyapubbaka Bhikkhu Vatthu-The Right Vehicle To Nibbana

Surely not on mounts like these

one goes the Unfrequented Way

as one by self well-tamed

is tamed and by the taming goes.

Explanation: Indeed, not be any means of transport can one

go to the place one has never been before, but by thoroughly taming

oneself, the tamed one can get to that place - Nibbana.

1. The tamed one: One, who having first controlled the senses, has later

developed Magga Insight. (The Commentary)

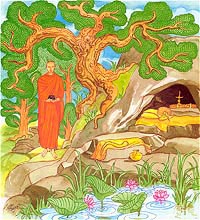

The Story of the Bhikkhu Who Had Been a Trainer of Elephants

While residing at the Jetavana monastery, the Buddha uttered Verse (323) of

this book, with reference to a bhikkhu who had previously been an elephant

trainer.

On one occasion, some bhikkhus saw an elephant trainer and his elephant on

the bank of the river Aciravati. As the trainer was finding it difficult to

control the elephant, one of the bhikkhus, who was an ex-elephant trainer, told

the other bhikkhus how it could be easily handled. The elephant trainer hearing

him did as told by the bhikkhu, and the elephant was quickly subdued. Back at

the monastery, the bhikkhus related the incident to the Buddha. The Buddha

called the ex-elephant trainer bhikkhu to him and said, “O vain bhikkhu,

who is yet far away from Magga and Phala ! You do not gain anything by taming

elephants. There is no one who can get to a place where one has never been

before (i.e.. Nibbana) by taming elephants; only one who has tamed himself can

get there.”

Then the Buddha spoke in verse as follows:

| Verse 323: Indeed, not by any means of transport (such as elephants and horses) can one go to the place one has never been before (i.e., Nibbana); but by thoroughly taming oneself, the tamed one can get to that place (i.e., Nibbana). SF Bay Area Aquariums

BSP warns of another food grains scam in UPLucknow: Warning the Uttar “There is every possibility of another food grains scam like the one in The BSP leader said that despite Chief Minister Akhilesh Yadav himself The BSP leader was also critical of minister of food and civil supplies “Giving him the same department is like giving him green signal to To a question on the twin constituencies of Congress president Sonia |

29 08 2012 Wednesday LESSON 688 FREE ONLINE eNālāndā Research and Practice UNIVERSITY

through

http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org

Tipitaka network … his life, his acts, his words

sabbe satta bhavantu sukhi-tatta

TIPITAKA ![]() மூன்று கூடைகள்— The words of the Buddha புத்தரின் வார்த்தைகள்—Majjhima மத்திம Nikāya

மூன்று கூடைகள்— The words of the Buddha புத்தரின் வார்த்தைகள்—Majjhima மத்திம Nikāya

நடுத்தரமான நீள அளவு திரட்டுகள் -Sabbāsava Sutta எல்லா களங்கங்களின் நெறி முறைக் கட்டளை ஆணை (contd)

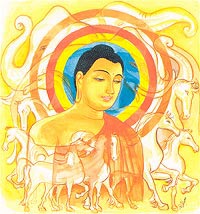

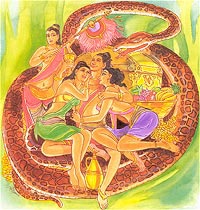

Dhammapada Verses 320, 321 and 322 Attadanta Vatthu-Verse 320. The Buddha’s Endurance-Verse 321. The Disciplined Animal-Verse 322. The Most Disciplined Animal

|

Verse 320. The Buddha’s Endurance

Explanation: I will endure the words of the unvirtuous, who |

|

Verse 321. The Disciplined Animal

Explanation: It is the disciplined animal (elephant or horse) |

|

Verse 322. The Most Disciplined Animal

Explanation: When well trained, mules are useful. Sindu thoroughbreds |

Dhammapada Verses 320, 321 and 322

Attadanta VatthuAham nagova sangame

capato patitam saram

ativakyam titikkhissam

dussilo hi bahujjano.Dantam nayanti samitim

dantam raja’ bhiruhati

danto settho manussesu

yo’ tivakyam titikkhati.Varamassatara danta

ajaniya ca sindhava

kunjara ca mahanaga

attadanto tato varam.Verse 320: As an elephant in battlefield withstands the arrow shot from a

bow, so shall I endure abuse. Indeed, many people are without morality.Verse 321: Only the trained (horses and elephants) are led to gatherings of

people; the King mounts only the trained (horses and elephants). Noblest among

men are the tamed, who endure abuse.Verse 322: Mules, thoroughbred horses, horses from Sindh, and great elephants

are noble only when they are trained; but one who has tamed himself (through

Magga Insight) is far nobler.

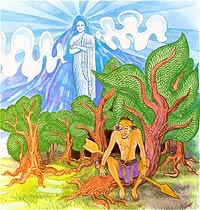

On Subduing Oneself

While residing at the Ghositarama monastery, the Buddha uttered Verses (320),

(321) and (322) of this book, with reference to the patience and endurance

manifested by himself when abused by the hirelings of Magandiya, one of the

three queens of King Udena.Once, the father of Magandiya, being very much impressed by the personality

and looks of the Buddha, had offered his very beautiful daughter in marriage to

Gotama Buddha. But the Buddha refused his offer and said that he did not like to

touch such a thing which was full of filth and excreta, even with his feet. On

hearing this remark both Magandiya’s father and mother discerning the truth of

the remark attained Anagami Fruition. Magandiya, however, regarded the Buddha as

her arch enemy and was bent on having her revenge on him.Later, she became one of the three queens of King Udena. When Magandiya heard

that the Buddha had come to Kosambi, she hired some citizens and their servants

to abuse the Buddha when he entered the city on an alms-round. Those hirelings

followed the Buddha and abused him using such abusive words as ‘thief, fool,

camel, donkey, one bound for niraya’. Hearing those abusive words, the Venerable

Ananda pleaded with the Buddha to leave the town and go to another place. But

the Buddha refused and said, “In another town also we might be abused

and it is not feasible to move out every time one is abused. It is better to

solve a problem in the place where it arises. I am like an elephant in a

battlefield; like an elephant who withstands the arrows that come from all

quarters, I also will bear patiently the abuses that come from people without

morality.”Then the Buddha spoke in verse as follows:

Verse 320: As an elephant in battlefield

withstands the arrow shot from a bow, so shall I endure abuse. Indeed,

many people are without morality.Verse 321: Only the trained (horses and elephants)

are led to gatherings of people; the King mounts only the trained

(horses and elephants). Noblest among men are the tamed, who endure

abuse.Verse 322: Mules, thoroughbred horses, horses from

Sindh, and great elephants are noble only when they are trained; but

one who has tamed himself (through Magga Insight) is far nobler.

At the end of the discourse, those who had abused the Buddha realized their

mistake and came to respect him; some of them attained Sotapatti Fruition.

Photography in San Francisco

watch

http://investigation.discovery.com/videos/alcatraz-videos/

http://vimeo.com/1635766

This was an HDR time-lapse from Twin Peaks. It

was a glorious moment because mother nature was behaving, unlike the

last 2 early morning efforts where I was too fogged in. I was also

shooting with my new Nikon D700 and a new 14-24mm ultrawide which is

just a great combo since the D700 is a full frame camera!San Francisco Walks & Hikes - Photos

Photos

of self-guided walks throughout San Francisco and the Bay Area. If you

came to San Francisco with the intent to just walk, you’d have days of

discovery and enjoyment. Unlike hot climates where summer heat makes

walking prohibitive . . . or rainy climes where duckies and mud might be

the norm . . . San Francisco’s weather is an ideal blend of clear days

and subsequent, cooling fog.San Francisco Neighborhood Photos

Photos

of San Francisco neighborhoods. The districts of San Francisco imbue

the city with its diverse colors, flavors and character. Although the

precise delineations can be hazy, the ethnic and demographic

distinctions are often vivid . . . between the Mission and the Marina,

between the Outer Sunset and North Beach.watch

http://videos.howstuffworks.com/howstuffworks/78-how-san-francisco-works-san-francisco-city-guide-video.htm

How San Francisco Works: San Francisco City Guide

San Francisco Attractions & Landmarks

Photos

of San Francisco Landmarks. San Francisco is studded with immediately

identifiable icons, such as the Golden Gate Bridge. This picture gallery

will expand to include some of the more familiar images around San

Francisco, and also the lesser known attractions and places of interest

around the San Francisco Bay Area.Watch

http://sfist.com/2012/05/28/did_you_see_last_nights_golden_gate.php

Video: Golden Gate Bridge 75th Anniversary Fireworks Show!!

Fireworks cascade downward from the Golden Gate Bridge as part of the

span’s 75th anniversary celebration on Sunday, May 27, 2012, in San

Francisco. (AP)We’re neither very interested nor typically emotional over firework displays, but last night’s Golden Gate Bridge 75th anniversary

fiery finale changed everything. It was pretty damn spectacular.

Starting out with a shower of sparks leaping from the the bridge, the

fireworks show blew up from there, gloriously. Check it out:http://family.go.com/video/slideshow-of-golden-gate-bridge-612414-v/

Slideshow of Golden Gate Bridge

San Francisco Parks & Nature Scenes

Photos

of San Francisco parks, nature and art works. One of the benefits and

joys of living in the San Francisco Bay Area is the overwhelming natural

beauty. From city parks to wilderness areas outside the city — trails,

wildlife, geological landmarks are all within a short walk, ride or

drive from the city.San Francisco Event Photos

Photos

of San Francisco events. Street fairs, festivals and public

competitions take place throughout the year in San Francisco. Some

events, like Bay to Breakers, attract hundreds of thousands of

participants and spectators. Others, like the St. Stupid’s Day Parade or

the Bring Your Own Big Wheel race, are often an accidental encounter

for tourists or newcomers who don’t know about these annual San

Francisco traditions.watch

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KkLfnB9jbIg

Bay Area Photos - Beyond SF

The

photos here include attractions, events, parks, and walking tours from

around the Bay Area — beyond the city limits of San Francisco.watch

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=50W-OX6qVUg

San Francisco Bay Area Scenic Flight

A scenic flight over San Francisco and featuring the Golden Gate bridge.

Music: Loro by Pinback. Many thanks to Bob Spofford for the flight.videos of San Francisco Alcatraz, Neighborhood, Twin Peaks,The Museums, Chinatown / North Beach, Haight Ashbury / Mission District, City Hall, The Ferry Building,Palace of Fine Arts / Exploratorium, The cemeteries.

San Francisco Ferry Building & Bay Bridge

San Francisco Streetcar - F Market

Market Bar - Embarcadero Side of Ferry Building

San Francisco Ferry Building Nave

Peets & Book Passage - San Francisco Ferry Building

Boulettes Larder - San Francisco Ferry Building

Ferry Plaza Wine Merchant

Recchiuti Confections - San Francisco Ferry Building

Cowgirl Creamery - San Francisco Ferry Building

Miette Patisserie - San Francisco Ferry Building

Imperial Tea Court - San Francisco Ferry Building

Tsar Nicoulai Caviar -

http://www.dailymotion.com/video/xnm9yz_ferry-building-san-francisco-engagement-photo_shortfilms

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LRYhmtMKld4

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PPbT5e7zbA8

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xnP9lJm1-2g

28 08 2012 Tuesday LESSON 687 FREE ONLINE eNālāndā Research and Practice UNIVERSITY

through

http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org

Tipitaka network … his life, his acts, his words

sabbe satta bhavantu sukhi-tatta

TIPITAKA ![]() மூன்று கூடைகள்— The words of the Buddha புத்தரின் வார்த்தைகள்—Majjhima மத்திம Nikāya

மூன்று கூடைகள்— The words of the Buddha புத்தரின் வார்த்தைகள்—Majjhima மத்திம Nikāya

நடுத்தரமான நீள அளவு திரட்டுகள் -Sabbāsava Sutta எல்லா களங்கங்களின் நெறி முறைக் கட்டளை ஆணை (contd)

Dhammapada Verses 318 and 319 Titthiyasvaka Vatthu-Verse 318. Right And Wrong-Verse 319. Right Understanding

Streets Inside Disneyland

|

Verse 318. Right And Wrong

Explanation: Those who take what is correct as incorrect, |

|

Verse 319. Right Understanding

Explanation: They regard error as error, and what is right |

Dhammapada Verses 318 and 319

Titthiyasvaka VatthuAvajje vajjamatino

vajje cavajjadassi no

micchaditthisamada

satta gacchanti duggatim.Vajjanca vajjato natva

avajjanca avajjato

sammaditthisamadana

satta gacchanti suggatim.Verse 318: Beings who imagine wrong in what is not wrong, who do not see

wrong in what is wrong, and who hold wrong views go to a lower plane of

existence (duggati).Verse 319: Beings who know what is wrong as wrong. who know what is right as

right, and who hold right views go to a happy plane of existence (suggati).

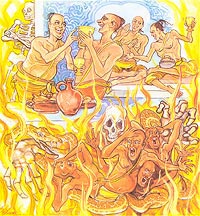

The Story of the Disciples of Non-Buddhist Ascetics

While residing at the Nigrodarama monastery, the Buddha uttered Verses (318)

and (319) of this book, with reference to some disciples of the Titthis

(non-Buddhist ascetics).The disciples of the Titthis did not want their children to mix with the

children of the followers of the Buddha. They often told their children,

“Do not go to the Jetavana monastery, do not pay obeisance to the bhikkhus

of the Sakyan clan.” On one occasion, while the Titthi boys were playing

with a Buddhist boy near the entrance to the Jetavana monastery, they felt very

thirsty. As the children of the disciples of the Titthis had been told by their

parents not to enter a Buddhist monastery, they asked the Buddhist boy to go to

the monastery and bring some water for them. The young Buddhist boy went to pay

obeisance to the Buddha after he had had a drink of water, and told the Buddha

about his friends who were forbidden by their parents to enter a Buddhist

monastery. The Buddha then told the boy to tell the non-Buddhist boys to come

and have water at the monastery. When those boys came, the Buddha gave them a

discourse to suit their various dispositions. As a result, those boys became

established in faith in the Three Gems i.e., the Buddha, the Dhamma and the

Samgha.When the boys went home, they talked about their visit to the Jetavana

monastery and about the Buddha teaching them the Three Gems. The parents of the

boys, being ignorant, cried, “Our sons have been disloyal to our faith,

they have been ruined,” etc. Some intelligent neighbours advised the

wailing parents to stop weeping and to send their sons to the Buddha. Somehow,

they agreed and the boys as well as their parents went to the Buddha.The Buddha knowing why they had come spoke to them in verse as

follows:

Verse 318: Beings who imagine wrong in what is not

wrong, who do not see wrong in what is wrong, and who hold wrong views

go to a lower plane of existence (duggati).Verse 319: Beings who know what is wrong as wrong.

who know what is right as right, and who hold right views go to a

happy plane of existence (suggati).

At the end of the discourse all those people came to be established in faith

in the Three Gems, and after listening to the Buddha’s further discourses, they

subsequently attained Sotapatti Fruition.End of Chapter Twenty-Two: Niraya

Disneyland Train

Disneyland Rides Main Street USA

City Hall

Fire Engine

Omnibus

Disneyland Rides Main Street USA

Horse-Drawn Streetcars

Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln

Disneyland Parade: Mickey’s Soundsational Parade

Disneyland Fireworks

Streets Inside Disneyland

Big Thunder TrailEast Center Street/West Center Street

East Plaza Street/West Plaza Street

Esplanade

Front Street

Main Street

Matterhorn Way

Mill View Lane

Neighborhood Lane

New Orleans Street

Orleans Street & Royal Street

Small World Way

Tomorrowland Way

The Disneyland Encyclopedia

Attractions at the Disneyland Resort

- Alice in Wonderland

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids

- Follow

the White Rabbit down the rabbit hole into the topsy-turvy realm of

Wonderland where cats disappear into thin air, giant flowers sing and

the spiteful Queen of Hearts commands a mad army of playing cards.- Animation Academy

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

- Learn the secrets of how to draw a classic Disney Character with a hands-on lesson from a Disney artist!

- Astro Orbitor

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens

Blast

off into the outer reaches of the solar system on this retro rocket

ride. Orbit the spiraling planets in your sleek ship that dips up and

down at your command!- Autopia

- Height:32″ (81 cm) or Taller

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

Take

the wheel and whirl around the tracks of this fun-filled roadway where

you can get glimpses of the world from the car’s perspective! Drivers of

almost all ages can experience the thrill of putting their pedal to the

metal on this imaginative motorway.- The Bakery Tour

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Kids, Adults

- Learn

the secrets of the 150-year-old process used to bake sourdough bread

while enjoying a glass-walled tour of the Boudin Bakery. Hosted by

Boudin® Bakery.- Big Thunder Mountain Railroad

- Height:40″ (102 cm) or Taller

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

- Hold

on to your hats and glasses, because you’re about to board a runaway

mine train through twisting desert canyons, creaking mine shafts and

pitch-black bat caverns on “the wildest ride in the wilderness!”- Big Thunder Ranch

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids

- Meet

and pet adorable barnyard animals, such as cows, goats, sheep, donkeys

and pigs on an idyllic western ranch right out of the 1880s. Presented

by Brawny.- Buzz Lightyear Astro Blasters

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

Help

save the galaxy when Buzz Lightyear recruits you as a Space Ranger to

thwart the Evil Emporer Zurg! Spin, twist and turn as you shoot lasers

at Zurg’s bad robots to keep them from carrying out his evil plan to

steal the batteries from good toys everywhere.- California Screamin’

- Height:48″ (122 cm) or Taller

- Ages:Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

- Shoot

forward up a steep incline and start screaming as you rip through the

air on this tubular ride! While it might look like a turn-of-the-century

wooden coaster, this state-of-the-art steel superstructure is ready to

rock you on Paradise Pier.- Captain EO Starring Michael Jackson

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

- An

enhanced version of the classic 3-D film musical Captain EO starring

Michael Jackson, is back. Fans of all ages can experience the magic of

this innovative film.- Casey Jr. Circus Train

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers

- All

aboard Casey Jr. for a charming ride around Storybook Land inside an

adorable miniature circus train complete with passenger cars that

resemble wild animal cages.- Character Close-Up

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids

- Character Close-Up is an exhibition of art from classic Disney animated movies, including the inventive Toy Story Zoetrope.

- Chip ‘n Dale Treehouse

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids

Play

like nuts! Chip ‘n Dale, the nuttiest twosome in Mickey’s Toontown, are

having a party in their treehouse and you’re invited. Scurry up the

spiral staircase in this giant Redwood tree to check out the digs and

enjoy the views. Kids of all ages are welcome. Stay as long as you like!- Davy Crockett’s Explorer Canoes

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

- Explore

the Rivers of America in a canoe as you paddle your way around Pirate’s

Lair on Tom Sawyer Island in search of adventure.- Disney Animation

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

- Explore

the place dedicated to the art of bringing Disney characters to life,

from pencil to pixel! From learning to draw at the Animation Academy to

chatting with Crush from Disney·Pixar’s Finding Nemo in an exciting live show, learn the secrets of how animators bring their imagination to the screen.- The Disney Gallery

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

- Discover

the fascinating artistry behind Disney magic at The Disney Gallery on

Main Street, U.S.A. On display are authentic sketches, renderings and

models by legendary Disney artists and Imagineers.- Disney Junior – Live on Stage!

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers

Join favorite Disney Junior Characters and see new ones at this live, rollicking, musical adventure!

- Disneyland Monorail

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

Ride

this “green” transportation system that rockets along a single rail

that circles the Disneyland Resort! Board at the Tomorrowland station or

the Downtown Disney District and sit back for a scenic trip.- Disneyland Railroad

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

- Board

an old-fashioned locomotive for a nostalgic trip around Disneyland

Park! These gorgeous Victorian-style trains stop at any of 4

destinations — Main Street U.S.A., New Orleans Square, Mickey’s Toontown

and Tomorrowland. So soak up the scenery on this grand circuit tour.- The Disneyland Story presenting Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

- The

Opera House hits a new high note with the return of this classic

attraction celebrating the 200th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth.

Learn about the Disneyland story and be inspired by the spectacular

speech of a man who changed the nation.- Disney Princess Fantasy Faire

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens

- Walk

an enchanting pathway with scenic alcoves perfect for greeting favorite

Disney Princesses — including Snow White, Cinderella, Aurora and Mula- Disney’s Aladdin – A Musical Spectacular

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

The genie is out of the lamp in this exciting, Broadway-style musical based on the classic animated Disney film, Aladdin. Starring a spunky princess and an unstoppable street urchin, this stage show is a wish come true!

- Donald’s Boat

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids

Attention

all would-be sailors! No one cries “fowl!” when you play on this

double-decker houseboat that resembles its owner. Climb the rope ladder,

scale the spiral staircase and help steer Donald’s pride and joy. Just

look for Donald’s sailor cap — you’ll quack up!- Duffy the Disney Bear

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids

Mickey has just returned from a worldwide tour with his brand new, handmade teddy bear, Duffy. Come meet Duffy at Paradise Pier!

- Dumbo the Flying Elephant

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

- Soar

through the air aboard a most unusual airborne animal on this iconic

Disneyland Park attraction that recreates the magical spectacle of Dumbo

the Flying Elephant.- Enchanted Tiki Room

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

- Hear a tropical serenade sung by a delightful chorus of enchanted birds, flowers and Tiki statues. Presented by Dole®.

- Fantasmic!

- Height:Any Height

Mickey’s

active imagination sets the stage for this musical, pyrotechnic

spectacular where the forces of good and evil battle in his dreams!

Marvel at the stunning effects that erupt against the broad night sky as

beloved Disney Characters join the reverie.- Finding Nemo Submarine Voyage

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

Dive into the Tomorrowland Lagoon and discover the world of Finding Nemo!

As your whimsical Australian submarine sinks into the vibrant waters,

explore the undersea curiosities and follow Marlin as he searches for

Nemo through the perils that dwell in the ocean deeps.- Flik’s Flyers

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids

- Hop

into a discarded food carton for a brief flight in Flik’s latest

invention! Fly in this contraption made of stitched leaves and twigs.

When you take a whirl, get a great view of “a bug’s land”!- Francis’ Ladybug Boogie

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids

- Take a spin to a famous swing tune as you ride on the “back” of a

Francis ladybug! The ladybugs run ’round each other on a fabulous figure

8 track. Even though Francis is no lady, he can teach you to boogie

like a bug!- Frontierland Shootin’ Exposition

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

- Line

up your sights on one of a gallery of animated targets and squeeze the

trigger of your infrared-light rifle. Hit a target to see and hear

entertaining animated effects.- Gadget’s Go Coaster

- Height:35″ (89 cm) or Taller

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens

Tumble,

twist and turn on this gentle rollercoaster ride created by that

inventive mouse from the Rescue Rangers, Gadget Hackwrench. Fashioned

from found objects, this coaster is one crazy invention sure to delight!

Presented by Sparkle.- Games of the Boardwalk

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

- Step

right up, ladies and gentlemen, and test your skill at one or all of

these turn-of-the-century-style games! Journey back to a time when the

midway was the best way to find fun. Rub your lucky rabbit’s foot or

kiss a four-leaf clover and let the games begin!- Golden Zephyr

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids

- Soar

around the gleaming red tower in a shining spaceship! Hearken back to

the 1920’s movie matinees when science fiction heroes saved the skies in

sleek silver ships that sailed through space. Imagine battling your own

Martian invaders as you fly into the future!- Goofy’s Playhouse

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids

Check

out the goofy goings-on at this most unusual house! See what’s growing

in Goofy’s garden, take a peek at his pumpkin patch, slide and climb all

around the yard. Then walk through Goofy’s house to check out the

unusual decorations, fun furniture and family photos.- Goofy’s Sky School

- Height:42″ (107 cm) or Taller

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

- The

wild blue yonder will get a little wilder thanks to Goofy’s Sky School.

This coaster-style ride is frantic fun, and with Goofy as your flight

instructor, you know that you’re in for a wild ride!- Grizzly River Run

- Height:42″ (107 cm) or Taller

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

- Take

a ride on the wild side with Grizzly River Run — a white-water rafting

adventure along the rapids of the Grizzly River and up the mountain

ominously known as Grizzly Peak. Your journey culminates with a

thrilling plunge down a runaway river.- Haunted Mansion

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

- Enter,

Mortals, if you dare! The “Haunted Mansion” is the elegant home of 999

ghosts, ghouls and goblins who are just dying to meet you! Could you be

their 1000th gloom-mate? Climb aboard your Doom Buggy for an eerie tour

of the place where a most spirited celebration awaits!- Heimlich’s Chew Chew Train

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids

- Heimlich

the Bavarian caterpillar invites you aboard his train for a sweet ride

through his meals, including a carrot, watermelon and animal crackers!- Indiana Jones Adventure

- Height:46″ (117 cm) or Taller

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

- Board

a rugged troop transport deep inside an overgrown ancient temple for an

unbelievable adventure filled with supernatural forces, screaming

mummies, giant snakes and the heroics of famed archeologist Indiana

Jones!- Innoventions

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

- Explore

the latest technologies with high-tech, interactive exhibits including

the Innoventions Dream Home, Project Tomorrow, the Xbox Experience, Say ‘Hello’ to Honda’s ASIMO and much more.- “it’s a small world”

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids

- Board

“the happiest cruise that ever sailed” for a joyful voyage through

iconic scenes from around the globe as you are serenaded by dolls

representing children from every nation — all living together in perfect

harmony. Presented by Sylvania.- It’s Tough to Be a Bug!

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

- Wonder

what it’s like to be a bug? To have humans hunt you down at every turn

with sprays and magnifying glasses? Flik the ant invites you to view the

world through “bug eyes” to get a little perspective. We’d all be in

big trouble without bugs — and now you know why!- Jumpin’ Jellyfish

- Height:40″ (102 cm) or Taller

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids

- Sail

straight up 40 feet into the air and drift back down like a jellyfish

in this experience that’s enough to make you jump for joy. With your

billowing parachute, ride in a giant jellyfish while a towering kelp

garden maintains the feeling that you are underwater.- Jungle Cruise

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

- Embark

on a guided tour aboard a tramp steamer deep into the unexplored

jungles of that world — filled with exotic animals and potential perils.- King Arthur Carrousel

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids

- Gallop up and down on the back of one of 68 graceful white steeds as you recreate the legend of Camelot.

- King Triton’s Carousel

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids

- The

only horse you’ll find on this unique marine carousel is a seahorse.

Triton’s bejeweled, aquatic carousel also features colorful flying fish,

musical whales, dancing dolphins, silly sea lions and seaworthy music

to set them all spinning!- The Little Mermaid ~ Ariel’s Undersea Adventure

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:All Ages

- Journey

under the sea and find out exactly what it’s like to be part of Ariel’s

world on this sensational new attraction filled with music and favorite

characters from The Little Mermaid!- Luigi’s Flying Tires

- Height:32″ (81 cm) or Taller

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

Float on a cushion of air aboard an oversized tire, thanks to Luigi from the Disney·Pixar movie Cars. Slide, glide and laugh as you lift slightly off the ground on a Fettuccini-brand tire.

- Mad Tea Party

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

- Spin round and round inside a giant multi-colored teacup as you celebrate a very merry unbirthday!

- Main Street Cinema

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

- Catch

a flick starring Mickey, Minnie and the rest of the gang in this old

fashioned movie house that plays film classics on 6 different screens.

Don’t miss the 1928 short Steamboat Willie, the first synchronized-sound cartoon, where Mickey and Minnie made their debut!- Main Street Vehicles

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

- Climb

aboard a vintage vehicle for a ride back in time. Whether it’s a fiery

red fire engine, a horse-drawn carriage or one of those new fangled

cars, there’s nothing like a Main Street U.S.A. vehicle for a one-way,

turn-of-the-century trip. Presented by National Car Rental.- The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids

- Bounce

up and down on a magical journey through the Hundred-Acre Woods for a

whimsical visit with Eeyore, Kanga, Roo, Rabbit, Piglet, Owl, Tigger and

most of all Winnie the Pooh!- Merida and Friends

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, All Ages

Come

to the Fairytale Garden in Disneyland Park to meet the adventurous

heroine Merida and the playful bear trio from Disney•Pixar’s movie Brave.- Mark Twain Riverboat

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

- Embark

on a 14-minute sightseeing voyage aboard an authentic recreation of the

glorious paddlewheel riverboats that steamed up and down the

Mississippi River in the 19th-century American wilderness.- Mater’s Junkyard Jamboree

- Height:32″ (81 cm) or Taller

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

Come on down for a tow-tappin’ square dance hosted by Mater from the Disney·Pixar movie Cars! Board a trailer pulled by an adorable little tractor and swing in time to the lively music.

- Matterhorn Bobsleds

- Height:42″ (107 cm) or Taller

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

- Slide

down Matterhorn Mountain on a daring bobsled run past icy slopes,

through twisting caves, near plunging waterfalls, over stone bridges,

and maybe even experience a thrilling encounter with the legendary

abominable snowman.- Mickey’s Fun Wheel

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

- Sail

’round the glimmering face of iconic Mickey on this swing-sational

Ferris wheel! Ride in one of the traditional gondolas mounted to the

outer rim or dare to board one of the 16 “free-mounted” gondolas that

slip and slide back and forth along the inside spokes.- Mickey’s House and Meet Mickey

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens

Glimpse

the inside of a star’s home! See how Mickey lives as you take a

self-guided tour through his living and work spaces packed with

artifacts from his daily life and brilliant career.- Minnie’s House

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens

Drop

in for a visit to see that her house is as charming and cute as Minnie

herself. If you’re in the mood for food, cake’s already rising (and

falling!) in the oven. And whisper what you want at her Wishing Well —

Minnie’s voice returns good wishes to all!- Monsters, Inc. Mike & Sulley to the Rescue!

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

- Climb

aboard a Monstropolis City Cab and embark on a wild ride through the

streets of Monstropolis. Follow the escapades of Mike and Sulley as they

race to return Boo to her bedroom before the trucks, helicopters and

the Child Detection Agency find her first!- Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

- Zig

and zag your way through a frenzied adventure aboard an out-of-control

vintage motorcar. Join Mr. Toad on a madcap journey through Toad Hall

and across the English countryside to “nowhere in particular.”- Muppet*Vision 3D

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

- Get

a zany, behind-the-scenes look at the Muppet’s new 3D special effects

laboratory in this wacky 3D film! Watch eye-popping pie slinging and

other “cheap shots” as Kermit, Miss Piggy and other Muppets show off the

latest in their cutting-edge, movie-making technology.- Peter Pan’s Flight

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids

- Soar

from London to Never Land island in a flying pirate galleon and watch

the daring adventures of Peter Pan as he confronts his dreaded

arch-nemesis, Captain Hook.- Pinocchio’s Daring Journey

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens

- Follow

the colorful misadventures of an enchanted wooden puppet who wishes to

be a real boy. Hop aboard a woodcarvers cart and journey to Geppetto’s

Toy Shop, Stromboli’s Puppet Theatre and Pleasure Island — then escape a

perilous encounter with Monstro the Whale.- Pirate’s Lair on Tom Sawyer Island

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

- Pirate

recruits are invited to sail on a raft across the Rivers of America for

jolly adventures on an island filled with twisting wilderness paths,

tree house lookouts and dark caverns filled with cursed treasure.- Pirates of the Caribbean

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

- As

nighttime bruises the waters of the bayou, cruise deep into the caverns

where pirates carouse and behave most abominably. Fireflies light the

way as you discover the adventures of these pillaging privateers — not

to mention the shenanigans of Captain Jack Sparrow!- Pixie Hollow – Tinker Bell & Her Fairy Friends

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens

- Shrink

down to the size of a fairy as you walk through an enchanted garden on

your way to a magical meeting with Tinker Bell herself — as well as her

pixie friends Silvermist, Iridessa, Fawn and Rosetta.- Princess Dot Puddle Park

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids

- Don’t

be bugged if you get a little wet in this watery play area that

features more than one way to cool off. Play under the spray as an

oversized hose nozzle and giant spigot spurt water. Everyone from the

smallest larva to the biggest bug will think these jumbo garden gadgets

are cool!- Radiator Springs Racers

- Height:40″ (102 cm) or Taller

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

Kick

the fun into overdrive as you rocket through the desert landscape in a

thrilling auto racing competition and visit memorable locations from the

Disney·Pixar movie Cars. This massive new attraction is one the biggest rides ever at the Disneyland Resort!- Red Car Trolley

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

Hop aboard the Red Car Trolley for a scenic ride down Buena Vista

Street and through Hollywood Land. With 4 convenient stops, you can use

these vintage trolleys for either transportation or leisurely

sightseeing.- Redwood Creek Challenge Trail

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids

Swing on rope bridges, zip down slides, rock climb and explore in

this outdoor recreational area. Follow clues left by Russell and his dog

Dug, from Disney·Pixar’s Up, to earn Wilderness Explorer badges for your achievements! Some challenges have age and height requirements.- Roger Rabbit’s Car Toon Spin

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens

Hail a wacky taxi for the ride of your life as you spin through — and we do mean through

— Toontown as you follow the hare-raising adventures of Roger Rabbit.

The Weasels threaten to “rub out” Jessica Rabbit with a big dose of the

deadly Dip. Can Roger stop them?- Sailing Ship Columbia

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

- Feel

the brisk wind upon your face as you explore the Rivers of America

aboard a full-scale replica of the first American ship to sail around

the world.- Silly Symphony Swings

- Height:40″ (102 cm) or Taller

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

- Swing

through the air in your musical chair as Mickey attempts to conduct a

barnyard orchestra in a storm! As the tornado takes hold, your seat

rises higher, the carnival top tipping this way and that with a sweeping

view of Disney California Adventure Park.- Sleeping Beauty Castle Walkthrough

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

- Explore

the winding passageways hidden inside Sleeping Beauty Castle and view

dazzling miniature vignettes that bring to life the classic tale of

Princess Aurora and her evil nemesis Maleficent from the movie Sleeping Beauty.- Snow White’s Scary Adventures

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

- Venture into dark forests, creepy castles, dank dungeons, dark mines and slippery cliffs as you relive frightful moments from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. And, if you see an apple, don’t take a bite or it might be your last!

- Soarin’ Over California

- Height:40″ (102 cm) or Taller

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

- Soar

like an eagle on an exhilarating yet gentle simulated hang glider

flight over natural and manmade wonders from the State of California —

including the Golden Gate Bridge, Yosemite, Palm Springs, Malibu and

Disneyland Park.- Sorcerer’s Workshop

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

Sorcerer’s

Workshop is an interactive journey through 3 themed realms that reveal

the magical secrets used to bring Disney animation to life.- Space Mountain

- Height:40″ (102 cm) or Taller

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

Rocket

into the outer reaches of darkest space on this high-speed thrill ride

that blasts into the future and back. Board a sleek space ship and aim

for the stars as Mission Control counts down to the most daring launch

of your life!- Splash Mountain

- Height:40″ (102 cm) or Taller

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

- Splash down into a musical adventure filled with delightful critters and down-home backwoods charm. Inspired by Song of the South,

Splash Mountain is a water flume voyage that culminates in a thrilling

approximately 5-story plunge into the dreaded briar patch.- Starcade

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

Score

big when you discover this galactic game spot. At this hotspot for

video hotshots, this video arcade delivers out-of-this-world fun for

everyone!- Star Tours – The Adventures Continue

- Height:40″ (102 cm) or Taller

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

The

power of the Force and the magic of Disney combine combine to create

this stellar, digital 3D experience. Take off on exciting adventures to

out-of-this-galaxy Star Wars destinations. With multiple storylines and locations, riding once is not enough!- Storybook Land Canal Boats

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens

- Tour

charming miniature reproductions of locations from some of your

favorite Disney animated films aboard a brightly colored canal boat on a

delightful cruise through Storybook Land.- Rapunzel and Flynn Rider

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, All Ages

Have a brush with Rapunzel and Flynn Rider from Tangled, the Walt Disney Pictures film.

- Tarzan’s Treehouse

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens

- Climb

to towering heights above Adventureland and learn the tale of how

Tarzan was rescued as a baby, raised by a kindly gorilla and fell in

love with Jane. Colorful vignettes inside the massive tree house show

how Tarzan and Jane live in harmony with nature.- Toy Story Mania!

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

- Step

right up and become an honorary toy as you ride through these midway

games hosted by the beloved characters from Disney·Pixar’s Toy Story! Toss eggs, pop balloons, throw pies and more. From expert to beginner, everyone’s a winner!- Tuck and Roll’s Drive ‘Em Buggies

- Height:36″ (91 cm) or Taller

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids

- Drive

yourself buggy as you bump into others under the circus tent at P.T.

Flea’s circus. The acrobatic Tuck & Roll from Disney·Pixar’s A Bug’s Life put on quite a show while you are along for the ride.- Turtle Talk with Crush

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Pre-schoolers, Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults, All Ages

- Grab

some shell and take part in a righteous interactive chat with Crush,

the totally awesome sea turtle from the Disney·Pixar film, “Finding

Nemo.”- The Twilight Zone Tower of Terror

- Height:40″ (102 cm) or Taller

- Ages:Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

- Dare

to explore the horrors of the once-glamorous Hollywood Tower Hotel.

Take the elevator ride of your life and find out what happened that

fateful night when lightning struck — in The Twilight Zone!- Walt Disney Imagineering Blue Sky Cellar

- Height:Any Height

- Ages:Kids, Pre-teens & Teens, Adults

- Get

a special preview of the new attractions and entertainment coming to

Disney California Adventure Park. Learn about the creative process used

by Walt Disney Imagineers to develop future attractions.

24 to 27 08 2012 Friday to Monday LESSON 686 FREE ONLINE eNālāndā Research and Practice UNIVERSITY

through

http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org

Tipitaka network … his life, his acts, his words

sabbe satta bhavantu sukhi-tatta

TIPITAKA ![]() மூன்று கூடைகள்— The words of the Buddha புத்தரின் வார்த்தைகள்—Majjhima மத்திம Nikāya

மூன்று கூடைகள்— The words of the Buddha புத்தரின் வார்த்தைகள்—Majjhima மத்திம Nikāya

நடுத்தரமான நீள அளவு திரட்டுகள் -Sabbāsava Sutta எல்லா களங்கங்களின் நெறி முறைக் கட்டளை ஆணை (contd)

Dhammapada Verse 314 Issapakata Itthi Vatthu Verse 315

Sambahulabhikkhu Vatthu Verses 316 and 317

Nigantha Vatthu-Verse 314. Good Deeds Never Make You Repent-Verse 315. Guard The Mind-Verse 316. False Beliefs Lead To Hell-Verse 317. Fear And Fearlessness In Wrong Places

Universal Studios Hollywood Photos

|

Verse 314. Good Deeds Never Make You Repent

Explanation: It is better not to do an evil deed; an evil |

|

Verse 315. Guard The Mind

Explanation: As a border town is guarded both inside and outside, |

|

Verse 316. False Beliefs Lead To Hell

Explanation: Those who are ashamed of what they should not |

|

Verse 317. Fear And Fearlessness In Wrong Places

Explanation: There are some who are afraid of what they should |

Dhammapada Verse 314

Issapakata Itthi VatthuAkatam dukkatam seyyo

paccha tappati dukkatam

katanca sukatam seyyo

yam katva nanutappati.Verse 314: It is better not to do an evil deed; an evil deed torments one

later on. It is better to do a good deed as one does not have to repent for

having done it.

The Story of a Woman of Jealous Disposition

While residing at the Jetavana monastery, the Buddha uttered Verse (314) of

this book, with reference to a woman who was by nature very jealous.Once, a woman with a very strong sense of jealousy lived with her husband in

Savatthi. She found that her husband was having an affair with her maid. So one

day, she tied up the girl with strong ropes, cut off her ears and nose, and shut

her up in a room. After doing that, she asked her husband to accompany her to

the Jetavana monastery. Soon after they left, some relatives of the maid arrived

at their house and found the maid tied up and locked up in a room. They broke

into the room, untied her and took her to the monastery. They arrived at the

monastery while the Buddha was expounding the Dhamma. The girl related to the

Buddha what her mistress had done to her, how she had been beaten, and how her

nose and ears had been cut off. She stood in the midst of the crowd for all to

see how she had been mistreated. So the Buddha said, “Do no evil,

thinking that people will not know about it. An evil deed done in secret, when

discovered, will bring much pain and sorrow; but a good deed may be done

secretly, for it can only bring happiness and not sorrow.”Then the Buddha spoke in verse as follows:

Verse 314: It is better not to do an evil deed; an

evil deed torments one later on. It is better to do a good deed as one

does not have to repent for having done it.

At the end of the discourse the couple attained Sotapatti Fruition.

Dhammapada Verse 315

Sambahulabhikkhu VatthuNagaram yatha paccantam

guttam santarabahiram

evam gopetha attanam1

khano vo ma upaccaga

khanatita hi socanti

nirayamhi samappita.Verse 315: As a border town is guarded both inside and outside, so guard

yourself. Let not the right moment go by for those who miss this moment come to

grief when they fall into niraya.

1. evam gopetha attanam: so guard yourself; i.e., to guard the internal as

well as the external senses. The six internal senses (sense bases) are eye, ear,

nose, tongue, body and mind; the six external senses (sense objects) are visible

object, sound, odour, taste, touch and idea.

The Story of Many Bhikkhus

While residing at the Jetavana monastery, the Buddha uttered Verse (315) of

this book, with reference to a group of bhikkhus who spent the vassa in a border

town.In the first month of their stay in that border town, the bhikkhus were well

provided and well looked after by the townsfolk. During the next month the town

was plundered by some robbers and some people were taken away as hostages. The

people of the town, therefore, had to rehabilitate their town and reinforce

fortifications. Thus, they were unable to look to the needs of the bhikkhus as

much as they would like to and the bhikkhus had to fend for themselves. At the

end of the vassa, those bhikkhus came to pay homage to the Buddha at the

Jetavana monastery in Savatthi. On learning about the hardships they had

undergone during the vassa, the Buddha said to them “Bhikkhus, do not

keep thinking about this or anything else; it is always difficult to have a

carefree, effortless living. Just as the townsfolk guard their town, so also, a

bhikkhu should be on guard and keep his mind steadfastly on his body.”Then the Buddha spoke in verse as follows:

Verse 315: As a border town is guarded both inside and

outside, so guard yourself. Let not the right moment go by for those

who miss this moment come to grief when they fall into niraya.

At the end of the discourse those bhikkhus attained arahatship.

Dhammapada Verses 316 and 317

Nigantha VatthuAlajjitaye lajjanti

lajjitaye na lajjare

micchaditthisamadana

satta gacchanti duggatim.Abhaye thayadassino

bhaye cabhayadassino

micchaditthisamadana

satta gacchanti duggatim.Verse 316: Those beings who are ashamed of what should not be ashamed of, who

are not ashamed of what should be ashamed of, and who hold wrong views go to a

lower plane of existence (duggati).Verse 317: Those beings who see danger in what is not dangerous, who do not

see danger in what is dangerous, and who hold wrong views go to a lower plane of

existence (duggati).

The Story of the Nigantha Ascetics

While residing at the Jetavana monastery, the Buddha uttered Verses (316) and

(317) of this book, with reference to Nigantha ascetics, who covered only the

front part of their bodies.One day, some Niganthas went on an alms-round with their bowls covered with a

piece of cloth. Some bhikkhus seeing them commented, “These Nigantha

ascetics who cover the front part of the body are more respectable compared to

those Acelaka ascetics who go about without wearing anything.” Hearing this

comment, those ascetics retorted, “Yes, indeed, we do cover up our front

part (by covering our bowls); but we cover it up not out of shame in going

naked. We only cover up our bowls to keep away dust from our food, for even dust

contains life in it.”When the bhikkhus reported what the Nigantha ascetics said, the Buddha

replied, “Bhikkhus, those ascetics who go about covering only the front

part of their bodies are not ashamed of what they should be ashamed of, but they

are ashamed of what they should not be ashamed of; because of their wrong view

they would only go to bad destinations.”Then the Buddha spoke in verse as follows:

Verse 316: Those beings who are ashamed of what

should not be ashamed of, who are not ashamed of what should be

ashamed of, and who hold wrong views go to a lower plane of existence

(duggati).Verse 317: Those beings who see danger in what is

not dangerous, who do not see danger in what is dangerous, and who

hold wrong views go to a lower plane of existence (duggati).

At the end of the discourse many Nigantha ascetics became frightened and

joined the Buddhist Order.

Seeing Stars: The Studio Tours

100 Universal City Plaza,

Universal City, CA./ (818) 508-9600

Universal is unique among the various

Hollywood studio tours because their tour is only one part of a much larger

theme park experience.I’ll review Universal Studios Hollywood

in general on another page. (To read it, click

here.) This article will deal solely with the studio tour.In studio lingo, the “front lot” is where

you’ll find sound stages and offices, while the “back lot” is

where you’ll find the large outdoor sets that the public tends to think

of when they hear the words “movie studio”. These big back lots

are an endangered species in these days of on-location filming. Universal

Studios and Warner Bros are the only two studios which still have large

“back lots” filled with colorful sets.As such, their tours tend to be more interesting

than those at the other studios (e.g. Sony & Paramount, where what

visitors mostly see are the exteriors of sound stages). And because of

the large size of their back lots, both Warner Bros and Universal use trams

in their tour (while Sony and Paramount offer walking-only tours.) The

good side of this is that is the trams save visitors a good deal of walking.

The drawback is that a tram-based tour can seem more removed from the reality

of movie-making, and less personal than a walking tour.Warner Bros manages

to get around this potential drawback in two ways. First, they use tiny,

golf cart-sized vehicles, which limit the size of the tour group to an

intimate number of visitors - so that guests can easily ask questions of

their tour guide. Second, they allow visitors to get off the tram and explore

the “front lot” on foot, taking a peak inside places like the

wardrobe and prop departments, and seeing inside the sound stages. Guests

are even allowed to visit the current sets on foot at WB. The Universal

tour trams, on the other hand, are huge, noisy vehicles, which hold

hundreds of passengers on each trip. And, for better or worse, guests are

stuck on those trams for the entire 45-minute tour. The trams slow down

to let guests get a good look at the various streets and sets, but they

never stop and let people explore them on foot. (Ages ago, when the studio

learned that guests’ main wish was to visit the sets on foot, the studio’s

reaction was to build a few fake “streets” up in the amusement

area, filled with shops and restaurants, where guests could spend money.

They are still there today: a French street, a Western street, etc.)On the other hand, Universal spiced up their

tour with something that Warner Bros doesn’t try to offer: special effects

and unique “rides” within the tram ride. Not very authentic,

perhaps, but still entertaining. Like Universal Studios Hollywood itself,

the tram tour is part authentic studio tour and part show-biz razzle dazzle.

How you will react to this depends upon what you’re looking for. If you

want your studio tour spiced up with jumping mechanical sharks and simulated

earthquakes, Universal is the place to be. If you’re looking for authenticity

and Hollywood history, Warner Bros is the best bet.(However, Universal is now offering a new VIP

tour, which provides an experience similar to Warners, and offers a

much more intimate look at the movie-making side of the studio - albeit

at a high price. More about that later.)But enough with comparisons… Let’s get to the tour

itself.

I shot this photo

in 2007 - looking down on the Universal back lot (with Burbank in the distance).

Copyright © 2012-Gary

Wayne

Get an exclusive, behind-the-scenes look at how your favorite movies and TV shows are made on the Studio Tour.

Learn

the secrets behind King Kong, The Mummy, The Klumps and other big

Hollywood blockbusters revealed at the new Special Effects Stages. You

may even get your very own starring role!

Take

adventure to the next dimension in the all-new Shrek 4-Dâ„¢ - the

attraction that puts you in the action with hair-raising, eye-popping,

and butt-busting effects so real, all your senses will be on ogre-time.

The

Simpsons are visiting Krustyland, the low-budget theme park created by

famed TV personality and shameless product huckster Krusty the Clown!

Universal’s

House of Horrors is a frightening, scream as you go, walk through

inspired by some of the greatest Universal horror movies of all time.

The Adventures of Curious George / Coke Soak

Have fun with Curious George as you both explore this themed play area for children, and the young at heart.

Inside

Cyberdyne Systems Corporation, you’ll witness the unveiling of the new

Terminator robots - until a live, human rebel strike erupts around you

in an all-out cyber war that’ll have you ducking for cover!

The

hit motion picture comes surging to life in a spectacular tidal wave of

death-defying stunts, awesome explosions and an ocean of thrills!

This shot is backstage and you can see the launch which the skyboat sits upon.

Come

see what happens when the world’s most talented animal stars take over

the show! You’re sure to laugh and be amazed at this live performance.

Who knows, you may even co-star!

Treat yourself to the musical stylings of Jake, Elwood and the coolest blues band to ever take the stage!

Studio Center

Transformers: The Ride-3D is an immersive, next generation thrill ride blurring the line between fiction and reality.

Go

behind the scenes of Universal’s film legacy in this interactive

exhibit featuring authentic props, wardrobe and artifacts from past,

present and upcoming Universal productions.

Revenge of the Mummy - The Ride

Plunge

into the immortal terror of “The Mummy” on a roller coaster ride filled

with heart-pounding special effects and shocks at every turn!

Come

face-to-face with “living” dinosaurs, a 50-foot T-Rex, and a

treacherous plunge straight down an 84 foot vertical drop waterfall.

With 65 cool things to do, this truly is “The Entertainment Capital of LA”!

This October, the terror is real as Halloween Horror Nights comes to Universal Studios Hollywood.

At

this festival full of holiday cheer, you can celebrate with your little

ones, friends and family as you play in a winter playground of real

snow.

This article is about the district in Los Angeles. For information about the American film industry, see Cinema of the United States. For other uses, see Hollywood (disambiguation).

Hollywood — District of Los Angeles — The world-famous Hollywood Sign

Nickname(s): Tinseltown Location within Central Los Angeles

Location within Western Los Angeles

Coordinates: 34°6′0″N 118°20′0″W Country United States State California County County of Los Angeles City City of Los Angeles Incorporated 1903 Government • City Council Eric Garcetti, Tom LaBonge • State Assembly Mike Feuer (D), Vacant • State Senate Curren Price (D), Gilbert Cedillo (D) • U.S. House Xavier Becerra (D), Diane Watson (D), Henry Waxman (D) Area[1] • Total 24.96 sq mi (64.6 km2) Population (2000)[1] • Total 123,435 • Density 4,945/sq mi (1,909/km2) ZIP Code 90027, 90028, 90029, 90038, 90046, 90068 Area code(s) 323 Hollywood is a district in Los Angeles, California, United States situated west-northwest of downtown Los Angeles.[2] Due to its fame and cultural identity as the historical center of movie studios and movie stars, the word Hollywood is often used as a metonym of American cinema. Even though much of the movie industry has dispersed into surrounding areas such as West Los Angeles and the San Fernando and Santa Clarita Valleys, significant auxiliary industries, such as editing, effects, props, post-production, and lighting companies remain in Hollywood, as does the backlot of Paramount Pictures.

As a district within the Los Angeles city limits, Hollywood does not

have its own municipal government. There was an official, appointed by

the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce, who served as an honorary “Mayor of Hollywood” for ceremonial purposes only. Johnny Grant held this position from 1980 until his death on January 9, 2008.[3] No replacement for Grant has been named.http://www.themeparkinsider.com/reviews/photo.cfm?id=1051&park=1

Universal Studios Hollywood Photos

For complete reader ratings and reviews, visit Theme Park Insider’s Universal Studios Hollywood review page.

Transformers: The Ride 3D: The Grand Opening of Transformers: The Ride 3D at Universal Studios Hollywood, May 24, 2012. Photo submitted by Robert Niles

International Cafe: Photo submitted by Robert Niles

International Cafe: The roast beef sandwich with brie, arugula, and carmelized pecans. Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Terminator 2: 3D: Photo submitted by Robert Niles

The Adventures Of Curious George: Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Waterworld: Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Waterworld: Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Waterworld: Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Waterworld: Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Waterworld: Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Waterworld: Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Waterworld: Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Waterworld: Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Waterworld: Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Transformers: The Ride 3D: Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Transformers: The Ride 3D: Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Transformers: The Ride 3D:

Megatron battles Optimus Prime, in one of the climactic scenes of

Transformers: The Ride. Notice the real props positioned in front of the

rear-projection 3D screen. (Image is projected in 2D for this still

photograph.) Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Transformers: The Ride 3D:

Additional detail on the ceiling of the ride as you approach the unload

station - detail only best seen when walking through the ride with the

lights on. Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Transformers: The Ride 3D:

The one tactile Decepticon in the ride - the remains of Megatron,

hanging horizontally above the track. Watch his eyes when you’re on the

ride. Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Transformers: The Ride 3D:

Here’s more of the wreckage detail from the final scene - detail most

riders will miss as their attention turns to the screen with Optimus

Prime on the other side of the track. Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Transformers: The Ride 3D: At the end of the ride, after you crash through the roadway, you’ll end up here. Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Transformers: The Ride 3D:

The screen where Bumblebee and Sideswipe fight for the Allspark. The

real helicopter in the foreground will blend with additional helicopters

on the screen. Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Transformers: The Ride 3D: A side view of EVAC. Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Transformers: The Ride 3D: A front view of EVAC, the Autobot who serves as your ride vehicle, as seen during a construction walk-through in April 2012. Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Transformers: The Ride 3D: The opening screen in Transformers, as seen during a construction walk-through in April 2012. Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Special Effects Stage: Photo courtesy Universal Studios. Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Harry Potter Ride:

James and Oliver Phelps, the Weasley twins from the Harry Potter films,

offer a Butterbeer toast during the announcement of Universal Studios

Hollywood’s Wizarding World of Harry Potter on Dec. 6, 2012. Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Jurassic Park - The Ride: Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Jurassic Park - The Ride: Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Transformers: The Ride 3D: The Transformers ride as of August 2011. Photo submitted by Manny Barron

Transformers: The Ride 3D: Transformers as of March 2011. Photo submitted by Manny Barron

The icon globe at the entrance to Universal Studios Hollywood. Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Flintstone’s Drive-In: Flintstones Drive-in Universal Studios Hollywood. Photo submitted by robert romero

Terminator 2: 3D: T2: 3D at Universal Studios Hollywood. Image courtesy Universal. Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Studio Tour: A statue right at the entrance of the Curse of the Mummy’s Tomb section. Photo submitted by Brandon Mendoza

Kwik-E-Mart Photo submitted by Brandon Mendoza

Creature From The Black Lagoon: The Creature from the Black Lagoon confronts his prey. Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Creature From The Black Lagoon: The first musical scene in the show. Photo submitted by Lucas Lee

Creature From The Black Lagoon: The new screen inside the theater. Photo submitted by Lucas Lee

Studio Tour: In the middle of the “Earthquake” sequence on the Universal Studios Hollywood Studio Tour. Photo submitted by Robert Niles

Studio Tour:

Formerly home of the Muensters, now home to one of the Desperate

Housewives of Wisteria Lane, on the Universal Studios Hollywood backlot.

Photo submitted by Robert Niles

The Simpsons Ride: The giant Krusty head durring the Christmas season. =) Photo submitted by Lucas Lee

Revenge of the Mummy: Entrance to Revenge of the Mummy the Ride Photo submitted by Manny Barron

Jurassic Park - The Ride: Welcome to Jurassic Park Photo submitted by Manny Barron

Jurassic Park - The Ride: Jurassic Park the Ride Photo submitted by Manny Barron

Entrance to Universal Studios Hollywood Photo submitted by Manny Barron

Special Effects Stages: Entrance to Special Effects Stages Photo submitted by Manny Barron

Backdraft: Entrance to Backdraft Photo submitted by Manny Barron

Shrek 4-D: Welcome to Shrek 4-D Photo submitted by Manny Barron

Universal’s Animal Actors: Universal’s Animal Actors Photo submitted by Manny Barron

The Simpsons Ride: Marge, Homer, Maggie, Bart, and Lisa aboard the Simpsons Ride Photo submitted by Manny Barron

The Simpsons Ride: Krustyland home of The Simpsons Ride Photo submitted by Manny Barron

Waterworld: The Water World set Photo submitted by Manny Barron

Studio Tour: The entrance to the world famous Studio Tour Photo submitted by Manny Barron

Terminator 2: 3D: Entrance to Terminator 2:3-D Photo submitted by Manny Barron

Halloween Horror Nights: Universal Studios Hollywood Halloween Horror nights Photo submitted by j capellino

Studio Tour: Flash Flood on the Studio Tour. Photo submitted by Brandon Mendoza

Waterworld: The Mariner being chased by a Smoker on Jet Ski’s. Photo submitted by Brandon Mendoza

Studio Tour: Lyon Estates Sign from Back to the Future Photo submitted by Brandon Mendoza

The Simpsons Ride:

One of the many posters of Krustyland’s “attractions”… this one is of

Captain Dinosaur’s Pirate Rip-off… wait time: 300 minutes! Photo submitted by Brandon Mendoza