through

http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org

sabbe satta bhavantu sukhi-tatta

TIPITAKA

TIPITAKA AND TWELVE DIVISIONS

Brief historical background

Sutta Pitaka

Vinaya Pitaka

Abhidhamma Pitaka

Twelve Divisions of Buddhist Canons

Nine Divisions of Buddhist Canons

Sutta Piṭaka

— The basket of discourses —Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Sutta (DN 22) {excerpt} - all infobubbles— Attendance on awareness —Kāyānupassanā

IV. சட்டத்துக்கு அடிப்படையான அற முறைகளின் கூர்ந்த கவனிப்பு

D.Bojjhaṅgas மீதான பிரிவு

Dhammapada Verse 291 Kukkutandakhadika Vatthu - When Anger Does Not Abate

ABOUT AWAKEN ONES WITH AWARENESS of Bhutan

Bumthang

• Kurjey Lhakhang - one of Bhutan’s most sacred temples - image of Guru Rinopche enshrined in rock.

Paro

• Rinpung Dzong

• Paro Taktsang (Tiger’s Nest) - perched on a 1,200 meter cliff, this is one of Bhutan’s most spectacular monasteries.

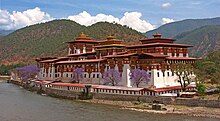

Punakha

• Punakha Dzong - constructed by Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal in 1637-38 it is the head monastery of the Southern Drukpa Kagyu school.

Phobjika

• Gangteng Monastery

Thimphu

• Chagri Monastery

BSP — created major uproar and repeated

adjournments in Parliament on Thursday forcing the Government to agree

to bring a Constitutional amendment bill for reservation in promotion of SC and STs in State Government jobs.

Raising the issue in Rajya Sabha, BSP chief Mayawati pointed out

she

had taken up the matter on April 30 in the House during the budget

session following which a debate took place on May 3. She said a general

consensus had then emerged for bringing a Constitutional amendment bill

to deal with a Supreme Court ruling on reservations in promotions.

She said the Government had then agreed to call an all-party meeting,

but it never took place.

During adjournment, Mayawati met the Prime Minister and discussed the

matter. Leader of Opposition Arun Jaitley also held talks with the

Prime Minister.

Minister of State for Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) informed the Upper House that a bill will be brought

in this regard on August 22 and Prime Minister Manmohan Singh will call a

meeting of leaders of all political parties on August 21 to discuss the

issue of SC/ST reservation.

The Government was forced to make this announcement as Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP)) raised a din in both Houses.

When he said the Government would call an all-party meeting

soon, BSP members protested vehemently and rushed into the well of the

House raising slogans. Chairman Hamid Ansari adjourned the House till noon.

Similar scenes were witnessed again when the House reassembled with

the BSP coming into the Well. Tariq Anwar, who

was in chair, adjourned the House for 15 minutes at about 12.10 pm

When the House met again, he made the announcement about bringing the bill on August 22.

Lok Sabha also witnessed uproar over the demand with the BSP

raising the matter as soon as the House assembled for the day.

Dara Singh Chauhan (BSP) demanded that the SC/ST employees should be

granted reservation in promotion in Government jobs immediately.

This sutta is widely considered as a the main reference for meditation practice.

Puna ca·paraṃ, bhikkhave, bhikkhu dhammesu dhammānupassī viharati, catūsu ariyasaccesu. Kathaṃ ca pana, bhikkhave, bhikkhu dhammesu cittānupassī viharati, catūsu ariyasaccesu? |

And furthermore, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu dwells observing dhammas in dhammas with reference to the four ariya·saccas. And furthermore, bhikkhus, how does a bhikkhu dwell observing dhammas in dhammas with reference to the four ariya·saccas? |

|

Idha, bhikkhave, bhikkhu ‘idaṃ dukkhaṃ’ ti yathā·bhūtaṃ pajānāti, ‘ayaṃ dukkha·samudayo’ ti yathā·bhūtaṃ pajānāti, ‘ayaṃ dukkha·nirodho’ ti yathā·bhūtaṃ pajānāti, ‘ayaṃ dukkha·nirodha·gāminī paṭipadā’ ti yathā·bhūtaṃ pajānāti. |

|

Katamaṃ ca, bhikkhave, dukkhaṃ ariya·saccaṃ? Jāti-pi dukkhā, jarā-pi dukkhā (byādhi-pi dukkho) maraṇam-pi dukkhaṃ, soka·parideva·dukkha·domanass·upāyāsā pi dukkhā, a·p·piyehi sampayogo dukkho, piyehi vippayogo dukkho, yampicchaṃ na labhati tam·pi dukkhaṃ; saṅkhittena pañc‘upādāna·k·khandhā dukkhā. |

தமிழ் E. இந்த சத்தியம் மேல் ஆன பகுதி மற்றும் இன்னமும், பிக்குளே, ஒரு பிக்கு, dhammas in dhammas சட்டத்துக்கு And what, bhikkhus, is the dukkha ariyasacca? Jāti is dukkha, aging is dukkha (sickness is dukkha) maraṇa is dukkha, sorrow, lamentation, dukkha, domanassa and distress is dukkha, association with what is disliked is dukkha, dissociation from what is liked is dukkha, not to get what one wants is dukkha; in short, the five upādāna·k·khandhas are dukkha. E1. Dukkhasacca துக்கச்சத்தியம் விளக்கிக்காட்டுதல் மற்றும் என்ன, பிக்குளே, dukkha ariyasacca துக்க மேதக்க மெய்ம்மை என்பது?Jāti is dukkha பிறப்பு என்பது துக்கம், மூப்படைதல் என்பது துக்கம் (நோய்நிலை என்பது துக்கம் )maraṇa மரணம் என்பது துக்கம், மனத்துயரம், புலம்பல், துக்கம்,domanassa மனதிற்குரிய கவலை சச்சரவு நோய் மற்றும் இடுக்கண் என்பது துக்கம், எது வெறுப்புடன் கூட்டமைகிரதோ கிடைக்காவிடில் எது வெறுப்புடன் கூட்டமைகிரதில்லையோ அது துக்கம், ஒருவருக்கு தேவைகள் கிடைக்காவிடில் அது துக்கம்,சுருக்கம், ஐந்து upādāna·k·khandhas பற்றாசைகளின் ஒன்று சேர்க்கை என்பவை துக்கம். |

|

Katamā ca, bhikkhave, jāti? Yā tesaṃ tesaṃ sattānaṃ tamhi tamhi satta-nikāye jāti sañjāti okkanti nibbatti abhinibbatti khandhānaṃ pātubhāvo āyatanānaṃ paṭilābho. Ayaṃ vuccati, bhikkhave, jāti. |

And what, bhikkhus, is jāti? For the various beings in the various classes of beings, jāti, the birth, the descent [into the womb], the arising [in the world], the appearance, the apparition of the khandhas, the acquisition of the āyatanas. This, bhikkhus, is called jāti. மற்றும் என்ன, பிக்குளே, jāti பிறப்பு என்பது? பல்வேறு வகைப்பட்ட உயிருரு களுக்கு பல்வேறு வகைப்பட்ட வர்க்கம்,jāti பிறப்பு, இந்த பரம்பரை |

|

Katamā ca, bhikkhave, jarā? Yā tesaṃ tesaṃ sattānaṃ tamhi tamhi satta-nikāye jarā jīraṇatā khaṇḍiccaṃ pāliccaṃ valittacatā āyuno saṃhāni indriyānaṃ paripāko: ayaṃ vuccati, bhikkhave, jarā. |

And what, bhikkhus, is jarā? For the various beings in the various classes of beings, jarā, மற்றும் என்ன, பிக்குளே, jarā முதுமை என்பது? பல்வேறு வகைப்பட்ட உயிருருகளுக்கு பல்வேறு வகைப்பட்ட வர்க்கம், jarā, பாழாகு நிலை உடைந்த பற்கள் உடையவராயிருத்தல், நரைமயிர் உடையவராயிருத்தல், திரைவிழ, சீவத்துவ இறக்கச்சரிவு,indriyas |

|

Katamaṃ ca, bhikkhave, maraṇaṃ? Yā tesaṃ tesaṃ sattānaṃ tamhi tamhi satta-nikāyā cuti cavanatā bhedo antaradhānaṃ maccu maraṇaṃ kālakiriyā khandhānaṃ bhedo kaḷevarassa nikkhepo, idaṃ vuccati, bhikkhave, maraṇaṃ. |

And what, bhikkhus, is maraṇa? மற்றும் என்ன, பிக்குளே, maraṇa மரணம் என்பது? பல்வேறு வகைப்பட்ட உயிருருகளுக்கு பல்வேறு வகைப்பட்ட வர்க்கம், இந்த சாவு, இந்த நடமாடும் நிலை, [வாழ்க்கைக்கு வெளியே ]இந்த கலைந்து செல்,இந்த மறைவு, இந்த சாதல், maraṇa மரணம், இந்த கழிதல், இந்த khandhas மொத்தை கற்பனையுருவ தோற்ற குவியல் கூறு கூறாக்கு, இந்த உயிரற்ற மனித உடல் கீழ் நோக்கி கிடப்பது: இது, பிக்குளே, maraṇa மரணம் என்பது. |

|

Katamo ca, bhikkhave, soko? Yo kho, bhikkhave, aññatar·aññatarena byasanena samannāgatassa aññatar·aññatarena dukkha·dhammena phuṭṭhassa soko socanā socita·ttaṃ anto·soko anto·parisoko, ayaṃ vuccati, bhikkhave, soko. |

And what, bhikkhus, is sorrow? In one, bhikkhus, associated with various kinds of misfortune, touched by various kinds of dukkha dhammas, the sorrrow, the mourning, the state of grief, the inner sorrow, the inner great sorrow: this, bhikkhus, is called sorrow. மற்றும் என்ன, பிக்குளே, மனத்துயரம் என்பது? ஒன்றில், பிக்குளே, பல்வேறு வகைப்பட்ட இணைக்கப்பட்ட இடர்ப்பாடு வகைகள், பல்வேறு வகைப்பட்ட dukkha dhammas துக்க தம்மா, இணைக்கப்பட்ட மனம் நெகிழவைத்தல், |

|

Katamo ca, bhikkhave, paridevo? Yo kho, bhikkhave, aññatar·aññatarena byasanena samannāgatassa aññatar·aññatarena dukkha·dhammena phuṭṭhassa ādevo paridevo ādevanā paridevanā ādevitattaṃ paridevitattaṃ, ayaṃ vuccati, bhikkhave, paridevo. |

And what, bhikkhus, is lamentation? In one, bhikkhus, associated with various kinds of misfortune, touched by various kinds of dukkha dhammas, மற்றும் என்ன, பிக்குளே, புலம்பல் என்பது? ஒன்றில், பிக்குளே, பல்வேறு வகைப்பட்ட இணைக்கப்பட்ட இடர்ப்பாடு வகைகள், பல்வேறு வகைப்பட்ட dukkha dhammas துக்க தம்மா, இணைக்கப்பட்ட மனம் நெகிழவைத்தல், இந்த மனத்துயரம், இந்த துயருறுதல், இந்த ஆழ்ந்த மனத்துன்ப நிலை, இந்த உட்புறமான மனத்துயரம், இந்த உட்புறமான அபார மனத்துயரம்: இது, பிக்குளே, புலம்பல் என்பது. |

|

Katamaṃ ca, bhikkhave, dukkhaṃ? Yaṃ kho, bhikkhave, kāyikaṃ dukkhaṃ kāyikaṃ a·sātaṃ kāya·samphassa·jaṃ dukkhaṃ a·sātaṃ vedayitaṃ, idaṃ vuccati, bhikkhave, dukkhaṃ. |

And what, bhikkhus, is dukkha? Whatever, bhikkhus, bodily dukkha, bodily unpleasantness, dukkha engendered by bodily contact, unpleasant vedayitas: this, bhikkhus, is called dukkha. மற்றும் என்ன, பிக்குளே, dukkha துக்கம் என்பது? என்னவாயினும் பிக்குளே, உடலைச் சார்ந்த துக்கம், உடலைச் சார்ந்த சச்சரவு, dukkha துக்கம் உடலைச் சார்ந்த தொடர்பான சுவேதசம், வெறுப்பு விளைக்கிற vedayitas உறுதலுணர்ச்சி அனுபவம்: இது, பிக்குளே, dukkha துக்கம் என்பது. |

|

Katamaṃ ca, bhikkhave, domanassaṃ? Yaṃ kho, bhikkhave, cetasikaṃ dukkhaṃ cetasikaṃ a·sātaṃ mano·samphassa·jaṃ dukkhaṃ a·sātaṃ vedayitaṃ, idaṃ vuccati, bhikkhave, domanassaṃ. |

And what, bhikkhus, is domanassa? Whatever, bhikkhus, mental dukkha, mental unpleasantness, dukkha engendered by mental contact, unpleasant vedayitas: this, bhikkhus, is called domanassa. மற்றும் என்ன, பிக்குளே, domanassa மனதிற்குரிய கவலை சச்சரவு நோய் மற்றும் இடுக்கண் என்பது? என்னவாயினும் பிக்குளே, உடலைச் சார்ந்த துக்கம், உடலைச் சார்ந்த சச்சரவு, dukkha துக்கம் உடலைச் சார்ந்த தொடர்பான சுவேதசம், வெறுப்பு விளைக்கிற vedayitas உறுதலுணர்ச்சி அனுபவம்: இது, பிக்குளே, domanassa மனதிற்குரிய கவலை சச்சரவு நோய் மற்றும் இடுக்கண் என்பது. |

|

Katamo ca, bhikkhave, upāyāso? Yo kho, bhikkhave, aññatar·aññatarena byasanena samannāgatassa aññatar·aññatarena dukkha·dhammena phuṭṭhassa āyāso upāyāso āyāsitattaṃ upāyāsitattaṃ, ayaṃ vuccati, bhikkhave, upāyāso. |

And what, bhikkhus, is despair? In one, bhikkhus, associated with various kinds of misfortune, touched by various kinds of dukkha dhammas, the trouble, the despair, the state of being in trouble, the state of being in despair: this, bhikkhus, is called despair. மற்றும் என்ன, பிக்குளே, நம்பிக்கையின்மை என்பது? ஒன்றில், பிக்குளே, பல்வேறு வகைப்பட்ட இணைக்கப்பட்ட இடர்ப்பாடு வகைகள், பல்வேறு வகைப்பட்ட dukkha dhammas துக்க தம்மா, இணைக்கப்பட்ட மனம் நெகிழவைத்தல்,இந்த நம்பிக்கையின்மை, இந்த துயருறுதல், இந்த ஆழ்ந்த மனத்துன்ப நிலை, இந்த உட்புறமான நம்பிக்கையின்மை, இந்த உட்புறமான அபார மனத்துயரம்:இது, பிக்குளே, நம்பிக்கையின்மை என்பது. |

|

Katamo ca, bhikkhave, a·p·piyehi sampayogo dukkho? Idha yassa te honti an·iṭṭhā a·kantā a·manāpā rūpā saddā gandhā rasā phoṭṭhabbā dhammā, ye vā pan·assa te honti an·attha·kāmā a·hita·kāmā a·phāsuka·kāmā a·yoga·k·khema·kāmā, yā tehi saddhiṃ saṅgati samāgamo samodhānaṃ missībhāvo, ayaṃ vuccati, bhikkhave, a·p·piyehi sampayogo dukkho. |

And what, bhikkhus, is the dukkha மற்றும் என்ன, பிக்குளே, dukkha துக்கத்துடன் இணைக்கப்பட்ட மனத்துக்கொவ்வாதது? இங்கு, படிவங்கள் படி, ஒலிகள், சுவைகள், வாசனைகள், உடலைச் சார்ந்த புலனுணர்வாதம் மற்றும் மன ஊன புலனுணர்வாதம், அங்கே எவை மகிழ்வில்லாதது இருக்கிரதோ, மகிழ்ச்சிகரமாக இல்லாத, வெறுப்பு உண்டாக்கு-கிற, இல்லாவிடில் யாரோ ஒருவரின் பாதகத்தால் ஆர்வ வேட்கை கொள்கிராரோ, ஒருவரின் நஷ்டத்தால் ஆர்வ வேட்கை கொள்கிராரோ, |

|

Katamo ca, bhikkhave, piyehi vippayogo dukkho? Idha yassa te honti iṭṭhā kantā manāpā rūpā saddā gandhā rasā phoṭṭhabbā dhammā, ye vā pan·assa te honti attha·kāmā hita·kāmā phāsuka·kāmā yoga·k·khema·kāmā mātā vā pitā vā bhātā vā bhaginī vā mittā vā amaccā vā ñāti·sālohitā vā, yā tehi saddhiṃ a·saṅgati a·samāgamo a·samodhānaṃ a·missībhāvo, ayaṃ vuccati, bhikkhave, piyehi vippayogo dukkho. |

And what, bhikkhus, is the dukkha மற்றும் என்ன, பிக்குளே, dukkha துக்கத்துடன் இணைக்கப்படாத மனத்துக்கொவ்வுவது? இங்கு, படிவங்கள் படி, ஒலிகள், சுவைகள், வாசனைகள், உடலைச் சார்ந்த புலனுணர்வாதம் மற்றும் மன ஊன புலனுணர்வாதம், அங்கே எவை மகிழ்வில்லாதது இருக்கிரதோ, மகிழ்ச்சிகரமாக இல்லாத, வெறுப்பு உண்டாக்கு-கிற, இல்லாவிடில் யாரோ ஒருவரின் பாதகத்தால் ஆர்வ வேட்கை கொள்கிராரோ, ஒருவரின் நஷ்டத்தால் ஆர்வ வேட்கை கொள்கிராரோ, ஒருவரின் உடல்நலமின்மையால் ஆர்வ வேட்கை கொள்கிராரோ, ஒருவரின் மனப்பற்றிலிருந்து விடுதலையாக ஆர்வ வேட்கை கொள்கிராரோ, பொழுதுபோக்கு-களியாட்டம் முதலியவற்றின் குழுமம், இணைக்கப்பட்டு இருத்தல், ஒன்று சேர்ந்து இருத்தல், அவைகளை எதிர்த்து நில்லுதல்: இது, பிக்குளே, இணைக்கப்படாத மனத்துக்கொவ்வும் dukkha துக்கம் என்பது. |

|

Katamaṃ ca, bhikkhave, yampicchaṃ na labhati tam·pi dukkhaṃ? Jāti·dhammānaṃ, bhikkhave, sattānaṃ evaṃ icchā uppajjati: ‘aho vata mayaṃ na jāti·dhammā assāma na ca vata no jāti āgaccheyyā’ ti. Na kho pan·etaṃ icchāya pattabbaṃ. Idaṃ pi yampicchaṃ na labhati tam·pi dukkhaṃ. |

And what, bhikkhus, is the dukkha மற்றும் எது, பிக்குளே, ஒருவருக்கு விருப்பப்பட்ட பொருள் பலன் தராததால் dukkha துக்கம்? இனங்களில், பிக்குளே, இந்த சென்மிப்பு என்ற சிறப்பியல்பு உடையவராயிருப்பதால், இது போன்ற ஒரு இச்சை எழும்புகிறது: “ஓ!! மெய்யாக, அங்கே எங்களுக்கு jāti பிறப்பு இன்றி இருக்கட்டும், மற்றும் மெய்யாக நாங்கள் jāti பிறக்க வராமல் இருக்கட்டும்.”ஆனால் இது விரும்புகிறதால் எய்தப் பெற முடியாது. ஒருவருக்கு விருப்பப்பட்ட பொருள் பலன் தராததால் ஏற்படும் dukkha துக்கம். |

|

Jarā·dhammānaṃ, bhikkhave, sattānaṃ evaṃ icchā uppajjati: ‘aho vata mayaṃ na jarā·dhammā assāma na ca vata no jarā āgaccheyyā’ ti. Na kho pan·etaṃ icchāya pattabbaṃ. Idaṃ pi yampicchaṃ na labhati tam·pi dukkhaṃ. |

In beings, bhikkhus, having the characteristic of getting old, such a wish arises: “oh really, may there not be jarā for us, and really, may we not come to jarā.” But this is not to be achieved by wishing. This is the dukkha of not getting what one wants. இனங்களில், பிக்குளே, இந்த முதுமை என்ற சிறப்பியல்பு உடையவராயிருப்பதால், இது போன்ற ஒரு இச்சை எழும்புகிறது: “ஓ!! மெய்யாக, அங்கே எங்களுக்கு jarā முதுமை இன்றி இருக்கட்டும், மற்றும் மெய்யாக எங்களுக்கு jarā முதுமை வராமல் இருக்கட்டும்.”ஆனால் இது விரும்புகிறதால் எய்தப் பெற முடியாது. ஒருவருக்கு விருப்பப்பட்ட பொருள் பலன் தராததால் ஏற்படும் dukkha துக்கம். |

|

Byādhi·dhammānaṃ, bhikkhave, sattānaṃ evaṃ icchā uppajjati: ‘aho vata mayaṃ na byādhi·dhammā assāma na ca vata no byādhi āgaccheyyā’ ti. Na kho pan·etaṃ icchāya pattabbaṃ. Idaṃ pi yampicchaṃ na labhati tam·pi dukkhaṃ. |

In beings, bhikkhus, having the characteristic of getting sick, such a இனங்களில், பிக்குளே, இந்த நோய் என்ற சிறப்பியல்பு உடையவராயிருப்பதால், இது போன்ற ஒரு இச்சை எழும்புகிறது: “ஓ!! மெய்யாக, அங்கே எங்களுக்கு நோய் இன்றி இருக்கட்டும், மற்றும் மெய்யாக எங்களுக்கு நோய் வராமல் இருக்கட்டும்.”ஆனால் இது விரும்புகிறதால் எய்தப் பெற முடியாது. ஒருவருக்கு விருப்பப்பட்ட பொருள் பலன் தராததால் ஏற்படும் dukkha துக்கம். |

|

Maraṇa·dhammānaṃ, bhikkhave, sattānaṃ evaṃ icchā uppajjati: ‘aho vata mayaṃ na maraṇa·dhammā assāma na ca vata no maraṇa āgaccheyyā’ ti. Na kho pan·etaṃ icchāya pattabbaṃ. Idaṃ pi yampicchaṃ na labhati tam·pi dukkhaṃ. |

In beings, bhikkhus, having the characteristic of getting old, such a wish arises: “oh really, may there not be maraṇa for us, and really, may we not come to maraṇa.” But this is not to be achieved by wishing. This is the dukkha of not getting what one wants. இனங்களில், பிக்குளே, இந்த முதுமை என்ற சிறப்பியல்பு உடையவராயிருப்பதால், இது போன்ற ஒரு இச்சை எழும்புகிறது: “ஓ!! மெய்யாக, அங்கே எங்களுக்கு maraṇa மரணம் இன்றி இருக்கட்டும், மற்றும் மெய்யாக எங்களுக்கு maraṇa மரணம் வராமல் இருக்கட்டும்.”ஆனால் இது விரும்புகிறதால் எய்தப் பெற முடியாது. ஒருவருக்கு விருப்பப்பட்ட பொருள் பலன் தராததால் ஏற்படும் dukkha துக்கம். |

|

Soka·parideva·dukkha·domanass·upāyāsa·dhammānaṃ, bhikkhave, sattānaṃ evaṃ icchā uppajjati: ‘aho vata mayaṃ na soka·parideva·dukkha·domanass·upāyāsa·dhammā assāma na ca vata no soka·parideva·dukkha·domanass·upāyāsa·dhammā āgaccheyyuṃ’ ti. Na kho pan·etaṃ icchāya pattabbaṃ. Idaṃ pi yampicchaṃ na labhati tam·pi dukkhaṃ. |

In beings, bhikkhus, having the characteristic of sorrow, lamentation, dukkha, domanassa and distress, such a wish arises: “oh really, may there not be sorrow, lamentation, dukkha, domanassa and distress for us, and really, may we not come to sorrow, lamentation, dukkha, domanassa and distress.” But this is not to be achieved by wishing. This is the dukkha of not getting what one wants. இனங்களில், பிக்குளே, இந்த அங்கலாய்ப்பு, புலம்பல், dukkha, domanassa துக்கம் மனதிற்குரிய கவலை சச்சரவு நோய் மற்றும் இடுக்கண் மற்றும் கடுந்துன்பம் என்ற சிறப்பியல்பு உடையவராயிருப்பதால், இது போன்ற ஒரு இச்சை எழும்புகிறது: “ஓ!! மெய்யாக, அங்கே எங்களுக்கு இந்த அங்கலாய்ப்பு,புலம்பல், dukkha, domanassa துக்கம் மனதிற்குரிய கவலை சச்சரவு நோய் மற்றும் இடுக்கண் மற்றும் கடுந்துன்பம் இன்றி இருக்கட்டும், மற்றும் மெய்யாக எங்களுக்கு இந்த அங்கலாய்ப்பு, புலம்பல், dukkha, domanassa துக்கம் மனதிற்குரிய கவலை சச்சரவு நோய் மற்றும் இடுக்கண் மற்றும் கடுந்துன்பம் வராமல் இருக்கட்டும்.”ஆனால் இது விரும்புகிறதால் எய்தப் பெற முடியாது. ஒருவருக்கு விருப்பப்பட்ட பொருள் பலன் தராததால் ஏற்படும் dukkha துக்கம். |

|

Katame ca, bhikkhave, saṅkhittena pañc‘upādāna·k·khandhā dukkhā? Seyyathidaṃ: rūp·upādānakkhandho vedan·upādānakkhandho saññ·upādānakkhandho saṅkhār·upādānakkhandho viññāṇ·upādānakkhandho. Ime vuccanti, bhikkhave, saṅkhittena pañc‘upādāna·k·khandhā dukkhā. |

And what, bhikkhus, are in short the five upādānakkhandhas? They are: the rūpa upādānakkhandha, the vedanā upādānakkhandha, the saññā upādānakkhandha, the saṅkhāra upādānakkhandha, the viññāṇa upādānakkhandha. These are called in short, bhikkhus, the five upādānakkhandhas. மற்றும் எது, பிக்குளே, சுருக்கமாக ஐம்புலன் என்ற இந்த ஐந்து upādānakkhandhas. அங்கே ஐந்து ஐக்கியப்படுத்தும் பற்றாசை எவை? அவை வருமாறு: இந்த rūpa upādānakkhandha சடப்பொருள் ஐக்கியப்படுத்தும் பற்றாசை, இந்த vedanā upādānakkhandha வேதனை உறுதலுணர்ச்சி புலன்றிவு அனுபவம் ஐக்கியப்படுத்தும் பற்றாசை, இந்த saññā upādānakkhandha விவேக வாயிற்காட்சி விழிப்புணர்வுநிலையை ஐக்கியப்படுத்தும் பற்றாசை, இந்த saṅkhāra upādānakkhandha, வரையறுக்கப்பட்ட புலனுணர்வாதம்/மனதிற்குரிய கட்டுமானங்கள்/மனதிற்குரிய கற்பனை/இச்சா சக்தி விருப்பம் உருவாக்குதல் ஐக்கியப்படுத்தும் பற்றாசை, இந்த viññāṇa upādānakkhandha. விழிப்புணர்வுநிலை/மனதை உணர்விற்கொள்ளும் பகுதி ஐக்கியப்படுத்தும் பற்றாசை. இவை சுருக்கமாக, பிக்குளே, ஐம்புலன் என்ற இந்த ஐந்து upādānakkhandhas என்பது. |

|

This is called, bhikkhus, the dukkha ariyasacca இது, பிக்குளே, இந்த dukkha ariyasacca துக்க மேதக்க மெய்ம்மை என அழைக்கபடுகிறது. |

Verse 291. When Anger Does Not Abate

Who so for self wants happiness

by causing others pain,

entangled in anger’s tangles

one’s from anger never free.

Explanation: The individual who achieves happiness by inflicting

pain on others is not freed from anger because he is entangled in

the web of anger due to the contact of the anger of other people.

Dhammapada Verse 291

Kukkutandakhadika Vatthu

Paradukkhupadhanena

athno sukhamicchati

verasamsaggasamsattho

vera so na parimuccati.

Verse 291: He who seeks his own happiness by inflicting pain on others, being

entangled by bonds of enmity, cannot be free from enmity.

The Story of the Woman Who Ate up the Eggs of a Hen

While residing at the Jetavana monastery, the Buddha uttered Verse (291) of

this book, with reference to a feud between a woman and a hen.

Once, there lived a woman in a village near Savatthi. She had a hen in her

house; every time the hen laid an egg she would eat it up. The hen was very much

hurt and angry and made a vow to have vengeance on the woman and made a wish

that it should be reborn as some being that would be in a position to kill the

offspring of that woman. The hen’s wish was fulfilled as it was reborn as a cat

and the woman was reborn as a hen in the same house. The cat ate up the eggs of

the hen. In their next existence the hen became a leopard and the cat became a

deer. The leopard ate up the deer as well as its offspring. Thus, the feud

continued for five hundred existences of the two beings. At the time of the

Buddha one of them was born as a woman and the other an ogress.

On one occasion, the woman was returning from the house of her parents to her

own house near Savatthi. Her husband and her young son were also with her. While

they were resting near a pond at the roadside, her husband went to have a bath

in the pond. At that moment the woman saw the ogress and recognized her as her

old enemy. Taking her child she fled from the ogress straight to the Jetavana

monastery where the Buddha was expounding the Dhamma and put her child at the

feet of the Buddha. The ogress who was in hot pursuit of the woman also came to

the door of the monastery, but the guardian spirit of the gate did not permit

her to enter. The Buddha, seeing her, sent the Venerable Ananda to bring the

ogress to his presence. When the ogress arrived, the Buddha reprimanded both the

woman and the ogress for the long chain of feud between them. He also added, “If

you two had not come to me today, your feud would have continued endlessly.

Enmity cannot be appeased by enmity; it can only be appeased by

loving-kindness.”

Then the Buddha spoke in verse as follows:

| Verse 291: He who seeks his own happiness by inflicting pain on others, being entangled by bonds of enmity, cannot be free from enmity. |

At the end of the discourse the ogress took refuge in the three Gems, viz.,

the Buddha, the Dhamma and the Samgha, and the woman attained Sotapatti

Fruition.

Bhutan

Bhutan Prime Minister has declared greed to be the cause of

the current global economic meltdown, and by extension, our great global

unhappiness. “We need to think Gross National Happiness,” insists the

Prime Minister.

Gross National Happiness is the Bhutanese government’s official alternative

to what it considers the “broken promise” of Gross National Product,

the traditional measure of a country’s economic output and worth.

Last year, Bhutan adopted a new Constitution centered on Gross National

Happiness, with agriculture, transportation, and foreign trade programs

now being judged not by their economic benefits, but by the happiness

they produce.

Jagatheesan Chandrasekharan · 69 years old

is within. Not out side. We are responsible for our own happiness and

Dukkha. Greed is the cause for Dukkha. Mind has to be trained to avoid

Dukkha including in USA.

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/07/world/asia/07bhutan.html?_r=2&scp=3&sq=%22Seth%20Mydans%22%20May%202009&st=Search

Recalculating Happiness in a Himalayan Kingdom

Under a new Constitution, government programs must be judged by the happiness they produce, not by the economic benefits.

|

Prayer flags above a monastery in the kingdom of 700,000. |

“Greed, insatiable human greed,” said Prime Minister Jigme Thinley of

Bhutan, describing what he sees as the cause of today’s economic

catastrophe in the world beyond the snow-topped mountains. “What we need

is change,” he said in the whitewashed fortress where he works. “We

need to think gross national happiness.”

The notion of gross national happiness

was the inspiration of the former king, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, in the

1970s as an alternative to the gross national product. Now, the

Bhutanese are refining the country’s guiding philosophy into what they

see as a new political science, and it has ripened into government

policy just when the world may need it, said Kinley Dorji, secretary of

information and communications.

“You see what a complete dedication to economic development ends up in,”

he said, referring to the global economic crisis. “Industrialized

societies have decided now that G.N.P. is a broken promise.”

Under a new Constitution adopted last year, government programs — from

agriculture to transportation to foreign trade — must be judged not by

the economic benefits they may offer but by the happiness they produce.

The goal is not happiness itself, the prime minister explained, a

concept that each person must define for himself. Rather, the government

aims to create the conditions for what he called, in an updated version

of the American Declaration of Independence, “the pursuit of gross

national happiness.”

The Bhutanese have started with an experiment within an experiment,

accepting the resignation of the popular king as an absolute monarch and

holding the country’s first democratic election a year ago.

The change is part of attaining gross national happiness, Mr. Dorji

said. “They resonate well, democracy and G.N.H. Both place

responsibility on the individual. Happiness is an individual pursuit and

democracy is the empowerment of the individual.”

It was a rare case of a monarch’s unilaterally stepping back from power,

and an even rarer case of his doing so against the wishes of his

subjects. He gave the throne to his son, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck,

who was crowned in November in the new role of constitutional monarch

without executive power.

Bhutan is, perhaps, an easy place to nimbly rewrite economic rules — a

country with one airport and two commercial planes, where the east can

only be reached from the west after four days’ travel on mountain roads.

No more than 700,000 people live in the kingdom, squeezed between the

world’s two most populous nations, India and China, and its task now is

to control and manage the inevitable changes to its way of life. It is a

country where cigarettes are banned and television was introduced just

10 years ago, where traditional clothing and architecture are enforced

by law and where the capital city has no stoplight and just one traffic

officer on duty.

If the world is to take gross national happiness seriously, the

Bhutanese concede, they must work out a scheme of definitions and

standards that can be quantified and measured by the big players of the

world’s economy.

“Once Bhutan said, ‘O.K., here we are with G.N.H.,’ the developed world

and the World Bank and the I.M.F. and so on asked, ‘How do you measure

it?’ ” Mr. Dorji said, characterizing the reactions of the world’s big

economic players. So the Bhutanese produced an intricate model of

well-being that features the four pillars, the nine domains and the 72

indicators of happiness.

Specifically, the government has determined that the four pillars of a

happy society involve the economy, culture, the environment and good

governance. It breaks these into nine domains: psychological well-being,

ecology, health, education, culture, living standards, time use,

community vitality and good governance, each with its own weighted and

unweighted G.N.H. index.

The New York Times

Thimphu, the capital, has one traffic officer and no stoplight.

All of this is to be analyzed using the 72 indicators. Under the domain

of psychological well-being, for example, indicators include the

frequencies of prayer and meditation and of feelings of selfishness,

jealousy, calm, compassion, generosity and frustration as well as

suicidal thoughts.

“We are even breaking down the time of day: how much time a person

spends with family, at work and so on,” Mr. Dorji said.

Mathematical formulas have even been devised to reduce happiness to its

tiniest component parts. The G.N.H. index for psychological well-being,

for example, includes the following: “One sum of squared distances from

cutoffs for four psychological well-being indicators. Here, instead of

average the sum of squared distances from cutoffs is calculated because

the weights add up to 1 in each dimension.”

This is followed by a set of equations:

= 1-(.25+.03125+.000625+0)

= 1-.281875

= .718

Every two years, these indicators are to be reassessed through a

nationwide questionnaire, said Karma Tshiteem, secretary of the Gross

National Happiness Commission, as he sat in his office at the end of a

hard day of work that he said made him happy.

Gross national happiness has a broader application for Bhutan as it

races to preserve its identity and culture from the encroachments of the

outside world.

“How does a small country like Bhutan handle globalization?” Mr. Dorji

asked. “We will survive by being distinct, by being different.”

Bhutan is pitting its four pillars, nine domains and 72 indicators

against the 48 channels of Hollywood and Bollywood that have invaded

since television was permitted a decade ago.

“Before June 1999 if you asked any young person who is your hero, the

inevitable response was, ‘The king,’ ” Mr. Dorji said. “Immediately

after that it was David Beckham, and now it’s 50 Cent, the rap artist.

Parents are helpless.”

So if G.N.H. may hold the secret of happiness for people suffering from

the collapse of financial institutions abroad, it offers something more

urgent here in this pristine culture.

“Bhutan’s story today is, in one word, survival,” Mr. Dorji said. “Gross

national happiness is survival; how to counter a threat to survival.”

THIMPHU, Bhutan

— If the rest of the world cannot get it right in these unhappy times,

this tiny Buddhist kingdom high in the Himalayan mountains says it is

working on an answer.

“Any form of violence is totally contradictory to the teachings of the

Buddha,” Tshiteem said, noting that Ahimsa (non-violence) “is a central

tenet in Buddhist philosophy.”

Mahayana Buddhism is the state religion of Bhutan, where a vast majority of the 700,000 citizens are Buddhist.

Gross National Happiness, which seeks to create an “awakened” society

in which government fosters the well-being of people as well as other

“sentient beings,” was first envisioned by Bhutan’s former King Jigme

Singye Wangchuck in 1972.

The landlocked Himalayan nation — about half the size of Indiana —

peacefully transitioned to democracy after the king abdicated power in

2006, but Buddhist principles continue to shape the country’s

government.

Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness index — as opposed to more

traditional measures like a nation’s economic activity — is based on

nine components of happiness: psychological well-being, ecology, health,

education, culture, living standards, time use, community vitality and good governance.

Because healthy family relationships are key to harmonious communities,

“attitudes accepting such behavior, in these relationships or even

outside, would be totally inconsistent” with Gross National Happiness,

Tshiteem said.

Bumthang

• Kurjey Lhakhang - one of Bhutan’s most sacred temples - image of Guru Rinopche enshrined in rock.

Paro

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kurjey_Lhakhang

| Kurjey Lhakhang Monastery | |

|---|---|

Kurjey Lhakhang Monastery |

|

|

|

|

| Coordinates: | 27°37′N 90°42′E |

| Monastery information | |

| Location | Bumthang valley, Bumthang district, Bhutan |

| Type | Tibetan Buddhist |

| Architecture | Dzong architecture |

Kurjey Lhakang, also known as Kurjey Monastery, is located in the Bumthang valley in the Bumthang district of Bhutan. This is the final resting place of the remains of the first three kings of Bhutan. Also, a large tree behind one of the temple buildings is believed to be a terma that was left there by Padmasambhava.

• Rinpung Dzong

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rinpung_Dzong

| Rinpung Dzong | |

|---|---|

Rinpung Dzong, Paro. photo by: Keith Mason |

|

|

|

|

| Coordinates: | 27°25′36″N 89°25′23.89″E |

| Monastery information | |

| Location | Paro, Paro District, Bhutan |

| Founded by | Drung Drung Gyal |

| Founded | 15th C. |

| Date renovated | 1644 by Shabdrung Ngawang Namgyal |

| Type | Himalayan Buddhist |

| Sect | Drukpa Kagyu |

| Lineage | Southern Drukpa |

| Architecture | Bhutanese Dzong |

| Festivals | Tsechu , in 2nd lunar month |

| Also known as Paro Dzong | |

Rinpung Dzong is a large Drukpa Kagyu Buddhist monastery and fortress in Paro District in Bhutan. It houses the district Monastic Body and government administrative offices of Paro Dzongkhag.

• Paro Taktsang (Tiger’s Nest) - perched on a 1,200 meter cliff, this is one of Bhutan’s most spectacular monasteries.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paro_Taktsang

| Taktsang Monastery | |

|---|---|

Taktsang |

|

|

|

|

| Coordinates: | 27°29′30.88″N 89°21′48.56″E |

| Monastery information | |

| Location | Paro Valley, Paro District, Bhutan |

| Founded | 8th century as a meditation cave (formally built as a monastery in 1692). |

| Date renovated | 1958 and 2005 |

| Type | Tibetan Buddhist |

| Sect | Drukpa Kagyu and Nyingma |

| Dedicated to | Guru Padmasambhava |

| Architecture | Bhutanese |

| Also known as the “Tiger’s Nest” | |

Paro Taktsang (spa phro stag tshang / spa gro stag tshang), is the popular name of Taktsang Palphug Monastery (also known as The Tiger’s Nest),[1] a prominent Himalayan Buddhist sacred site and temple complex, located in the cliffside of the upper Paro valley, Bhutan. A temple complex was first built in 1692, around the Taktsang Senge Samdup (stag tshang seng ge bsam grub) cave where Guru Padmasambhava is said to have meditated for three months in the 8th century. Padmasambhava is credited with introducing Buddhism to Bhutan and is the tutelary deity of the country. Today, Paro Taktsang is the best known of the thirteen taktsang or “tiger lair” caves in which he meditated.

The Guru mTshan-brgyad Lhakhang, the temple devoted to Padmasambhava

(also known as Gu-ru mTshan-brgyad Lhakhang, “The Temple of the Guru

with Eight Names”) is an elegant structure built around the cave in 1692

by Gyalse Tenzin Rabgye; and has become the cultural icon of Bhutan.[2][3][4] A popular festival, known as the Tsechu, held in honour of Padmasambhava, is celebrated in the Paro valley sometime during March or April.

Contents

Punakha

• Punakha Dzong - constructed by Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal in 1637-38 it is the head monastery of the Southern Drukpa Kagyu school.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Punakha_Dzong

| Punakha Dzong Pungtang Dechen Photrang Dzong |

|

|---|---|

| Punakha Dzong | |

Pungtang Dechen Photrang Dzong at Punakha and Jacaranda trees |

|

|

|

|

| Alternative names | Pungtang Dechen Photrang Dzong |

| General information | |

| Type | Religious and Civil Administration |

| Architectural style | Dzong |

| Location | Punakha, Bhutan |

| Coordinates | 27.6167°N 89.8667°E |

| Elevation | 1,200 |

| Construction started | 1637 |

| Completed | 1638 |

| Renovated | 2004 |

| Technical details | |

| Structural system | Fortress |

| Floor count | Six |

| Design and construction | |

| Owner | Government of Bhutan |

| Architect | Zowe Palep and Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal |

The Punakha Dzong, also known as Pungtang Dechen Photrang Dzong (meaning “the palace of great happiness or bliss”[1][2]) is the administrative centre of Punakha dzongkhag in Punakha, Bhutan. Constructed by Zhabdrung (Shabdrung) Ngawang Namgyal in 1637–38,[1][3] it is the second oldest and second largest dzong in Bhutan and one of its most majestic structures.[1][4] The Dzong houses the sacred relics of the southern Drukpa Kagyu school including the Rangjung Kasarpani, and the sacred remains of Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal and Terton Padma Lingpa. Punakha Dzong was the administrative centre and the seat of the Government of Bhutan until 1955, when the capital was moved to Thimphu.[2][4][5]

Contents

Phobjika

• Gangteng Monastery

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gangteng_Monastery

| Gangteng Monastery Gangteng Gönpa Gangteng Sangngak Chöling |

|

|---|---|

Entrance Gate to Gangteng Monastery after restoration |

|

|

|

|

| Coordinates: | 27°30′N 90°10′E |

| Monastery information | |

| Location | Wangdue Phodrang District, Bhutan |

| Founded by | Gyalsé Pema Thinley |

| Founded | In 1613 by Gyalsé Rinpoche Gangteng Tulku Rigdzin Pema Tinley (1564–1642) |

| Date renovated | October 2008 |

| Type | Tibetan Buddhist |

| Lineage | Nyingma |

| Head Lama | Rigdzin Kunzang Pema Namgyal |

| Architecture | Bhutanese Architecture |

| Festivals | Tsechu and Crane Festivals |

The Gangteng Monastery (Dzongkha: སྒང་སྟེང་དགོན་པ sometimes written “Gangtey Gonpa”, is an important monastery of Nyingmapa school of Buddhism, the main seat of the Pema Lingpa tradition.[1] located in the Wangdue Phodrang District in central Bhutan. The Monastery also known by the Gangten village that surrounds it, is in the Phobjika Valley where winter visitors – the Black-necked Cranes

– visit central Bhutan to roost and in the process circle the monastery

three times on arrival and repeat the process while returning to Tibet.[2]

The Monastery has a hoary history traced to early 17th century, backed

to prophecies made by the well known Terton (treasure finder) Pema

Lingpa in the late 15th century.[3][4]

The Monastery is one of the main seats of the religious tradition

based on Pema Lingpa’s revelations and one of the two main centres of

the Nyingmapa school of Buddhism in the country.[5]

A Nyingma monastic college or shedra, Do-ngag Tösam Rabgayling, has been established above the village.[5]

The descent of the first king of Bhutan, Ugyen Wangchuk

of the Wangchuk Dynasty of Bhutan, which continues to rule Bhutan is

traced to the clan of the Dungkhar Choje, a subsidiary of the clan of

Khouchung Choje whose founder was Kunga Wangpo, the fourth son of Pema

Lingpa.[6]

Contents

- 1 Geography

- 2 History

- 3 Structure

- 4 Gangtey trek

- 5 Festival

- 6 Throne Holders of Gangteng

- 7 Religious institutions

- 8 Gallery

- 9 References

- 10 External links

Thimphu

• Chagri Monastery

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chagri_Monastery

Chagri Monastery, Bhutan

Chagri Dorjeden Monastery also called “Cheri Monastery” is a Buddhist monastery in Bhutan established in 1620, by Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal.[1] the founder of the Butanese state.

The monastery, which is now a major teaching and retreat center of the Southern Drukpa Kagyu

order, is located at the northern end of Thimphu Valley about fifteen

kilometers from the capital. It sits on a hill above the end of the road

at Dodeyna and it takes about an hour to walk up the steep hill to

reach the monastery from there.

According to Bhutanese religious histories, the place was first visited by Padmasambhava in the 8th century. In the 13th century it was visited by Phajo Drugom Zhigpo the Tibetan Lama who first established the Drukpa Kagyu tradition in Bhutan.

Chagri Monastery, Bhutan

| [show]

Part of a series on Tibetan Buddhism |

|---|

Chagri Dorjeden was the first monastery established in Bhutan by

Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal in 1620 when he was 27 years old. Zhabdrung

spent three years in strict retreat at Chagri and resided there for many

periods throughout the rest of his life. It was at Chagri in 1623 that

he established the first Drukpa Kagyu monastic order in Bhutan.

| This article about a building or structure in Bhutan is a stub. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it. |

| This article about a Buddhist monastery, temple or nunnery is a stub. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it. |

THE BRAVE LITTLE BOWMAN

[55]

| O |

NCE upon a time there was a little man with a crooked back

who was called the wise little bowman because he used his bow

and arrow so very well. This crooked little man said to himself:

“If I go to the king and ask him to let me join his army,

he’s sure to ask what a little man like me is good for.

I must find some great big man who will take me as his page,

and ask the king to take us.” So the little bowman went about the city

looking for a big man.

One day he saw a big, strong man digging a ditch.

“What makes a fine big man like you do such work?” asked the little man.

“I do this work because I can earn a living in no other way,” said the big man.

“Dig no more,” said the bowman. “There is in this whole country

no such bowman as I am; but no king would let me join his army

because I am such a little man. I

[56] want you to ask the king to let you join the army.

He will take you because you are big and strong.

I will do the work that you are given to do,

and we will divide the pay. In this way we shall both of us

earn a good living. Will you come with me and do as I tell you?”

asked the little bowman.

“Yes, I will go with you,” said the big man.

So together they set out to go to the king.

By and by they came to the gates of the palace,

and sent word to the king that a wonderful bowman was there.

The king sent for the bowman to come before him.

Both the big man and the little man went in and,

bowing, stood before the king.

The king looked at the big man and asked, “What brings you here?”

“I want to be in your army,” said the big man.

“Who is the little man with you?” asked the king.

“He is my page,” said the big man.

“What pay do you want?” asked the king.

“A thousand pieces a month for me and my page, O King,” said the big man.

“I will take you and your page,” said the king.

So the big man and the little bowman joined the king’s army.

[57] Now in those days there was a tiger in the forest

who had carried off many people. The king sent for the big man

and told him to kill that tiger.

The big man told the little bowman what the king said.

They went into the forest together, and soon the little bowman shot the tiger.

The king was glad to be rid of the tiger,

and gave the big man rich gifts and praised him.

Another day word came that a buffalo was running up and down a certain road.

The king told the big man to go and kill that buffalo.

The big man and the little man went to the road,

and soon the little man shot the buffalo.

When they both went back to the king, he gave a bag of money to the big man.

The king and all the people praised the big man,

and so one day the big man said to the little man:

“I can get on without you. Do you think there’s no bowman but yourself?”

Many other harsh and unkind things did he say to the little man.

But a few days later a king from a far country

marched upon the city and sent a message to its king saying,

“Give up your country, or do battle.”

The king at once sent his army. The big man was armed

and mounted on a war-elephant. But the little bowman

[58] knew

that the big man could not shoot, so he took his bow

and seated himself behind the big man.

![[Illustration]](http://www.mainlesson.com/books/babbitt/morejataka/zpage058.gif)

Then the war-elephant, at the head of the army, went out of the city.

At the first beat of the drums, the big man shook with fear.

“Hold on tight,” said the little bowman.

“If you fall off now, you will be killed.

You need not be afraid; I am here.”

But the big man was so afraid that he slipped down

off

[59] the war-elephant’s back, and ran back into the city.

He did not stop until he reached his home.

“And now to win!” said the little bowman,

as he drove the war-elephant into the fight.

The army broke into the camp of the king that came from afar,

and drove him back to his own country.

Then the little bowman led the army back into the city.

The king and all the people called him “the brave little bowman.”

The king made him the chief of the army, giving him rich gifts.