through

http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org

sabbe satta bhavantu sukhi-tatta

TIPITAKA

TIPITAKA AND TWELVE DIVISIONS

Brief historical background

Sutta Pitaka

Vinaya Pitaka

Abhidhamma Pitaka

Twelve Divisions of Buddhist Canons

Nine Divisions of Buddhist Canons

Sutta Piṭaka

— The basket of discourses —Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Sutta (DN 22) {excerpt} - all infobubbles— Attendance on awareness —Kāyānupassanā

IV. சட்டத்துக்கு அடிப்படையான அற முறைகளின் கூர்ந்த கவனிப்பு

D.Bojjhaṅgas மீதான பிரிவு

Dhammapada Verses 292 and 293 Bhaddiyanam bhikkhunam Vatthu - Verse 292. How Blemishes IncreaseVerse 293. Mindfulness Of Physical Reality

ABOUT AWAKEN ONES WITH AWARENESS Cambodia

Prasat Angkor Wat

Angkor

• Angkor Wat

• Bayon

• Krol Ko

• Neak Pean

• Preah Khan

• Preah Palilay

• Ta Prohm

• Ta Som

Wat Preah Keo Morokot

Kampong Thom

• Prasat Kuh Nokor

Phnom Penh

• Wat Botum

• Wat Ounalom

• Wat Phnom

• Wat Preah Keo (Silver Pagoda)

Pursat

• Wat Bakan

|

Verse 292. How Blemishes Increase

Explanation: If people do what should not be done, and neglect |

|

Verse 293. Mindfulness Of Physical Reality

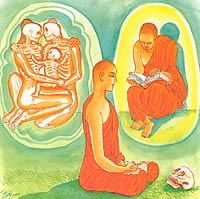

Explanation: If one were to practice constantly on the mindfulness |

Dhammapada Verses 292 and 293

Bhaddiyanam bhikkhunam VatthuYam hi kiccam apaviddham

akiccam pana kariyati

unnalanam pamattanam

tesam vaddhanti asava.Yesanca susamaraddha

niccam kayagata sati

akiccam te na sevanti

kicce sataccakarino

satanam Sampajananam

attham gacchanti asava.Verse 292: In those who leave undone what should indeed be done but do what

should not be done, who are conceited and unmindful, moral intoxicants increase.Verse 293: In those who always make a good effort in meditating on the body,

who do not do what should not be done but always do what should be done, who are

also mindful and endowed with clear comprehension, moral intoxicants come to an

end.

The Story of the Baddiya Bhikkhus

While residing near the town of Baddiya, the Buddha uttered Verses (292) and

(293) of this book, with reference to some bhikkhus.Once, some bhikkhus who were staying in Baddiya made some ornate slippers out

of some kinds of reeds and grasses. When the Buddha was told about this he said,

“Bhikkhus, you have entered the Buddhist Order for the sake of attaining

Arahatta Phala. Yet, you are now striving hard only in making slippers and

decorating them.”Then the Buddha spoke in verse as follows:

Verse 292: In those who leave undone what should

indeed be done but do what should not be done, who are conceited and

unmindful, moral intoxicants increase.Verse 293: In those who always make a good effort

in meditating on the body, who do not do what should not be done but

always do what should be done, who are also mindful and endowed with

clear comprehension, moral intoxicants come to an end.

At the end of the discourse, those bhikkhus attained arahatship.

Cambodia

Prasat Angkor Wat

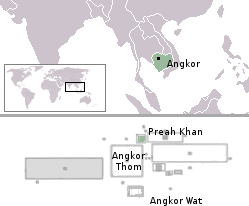

Angkor

• Angkor Wat

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angkor_Wat

| Angkor Wat | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Coordinates: | 13°24′45″N 103°52′0″ECoordinates: 13°24′45″N 103°52′0″E |

| Name | |

| Proper name: | Prasat Angkor Wat |

| Location | |

| Country: | Cambodia |

| Location: | Angkor, Siem Reap Province |

| Architecture and culture | |

| Primary deity: | Vishnu |

| Architectural styles: | Khmer, Dravidian |

| History | |

| Date built: (Current structure) |

12th century |

| Creator: | Suryavarman II |

Angkor Wat (Khmer: អង្គរវត្ត) is the largest Hindu temple complex in the world. The temple was built by King Suryavarman II in the early 12th century in Yasodharapura (Khmer: យសោធរបុរៈ, present-day Angkor), the capital of the Khmer Empire, as his state temple and eventual mausoleum. Breaking from the Shaivism tradition of previous kings, Angkor Wat was instead dedicated to Vishnu.

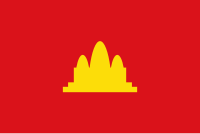

As the best-preserved temple at the site, it is the only one to have

remained a significant religious centre since its foundation – first

Hindu, dedicated to the god Vishnu, then Buddhist. The temple is at the top of the high classical style of Khmer architecture. It has become a symbol of Cambodia,[1] appearing on its national flag, and it is the country’s prime attraction for visitors.

Angkor Wat combines two basic plans of Khmer temple architecture: the temple mountain and the later galleried temple, based on early Dravidian Architecture, with key features such as the Jagati. It is designed to represent Mount Meru, home of the devas in Hindu mythology: within a moat

and an outer wall 3.6 kilometres (2.2 mi) long are three rectangular

galleries, each raised above the next. At the centre of the temple

stands a quincunx

of towers. Unlike most Angkorian temples, Angkor Wat is oriented to the

west; scholars are divided as to the significance of this. The temple

is admired for the grandeur and harmony of the architecture, its

extensive bas-reliefs, and for the numerous devatas adorning its walls.

The modern name, Angkor Wat, means “Temple City” or “City of Temples” in Khmer; Angkor, meaning “city” or “capital city”, is a vernacular form of the word nokor (នគរ), which comes from the Sanskrit word nagar (नगर).[2] Wat is the Khmer word for “temple grounds”, derived from the Pali word “vatta” (वत्त).[3] Prior to this time the temple was known as Preah Pisnulok (Vara Vishnuloka in Sanskrit), after the posthumous title of its founder.[4]

Contents

- 1 History

- 2 Architecture

- 3 Angkor Wat today

- 4 References

- 5 External links

-

History

King Suryavarman II, the builder of Angkor Wat

Angkor Wat lies 5.5 kilometres (3.4 mi) north of the modern town of Siem Reap, and a short distance south and slightly east of the previous capital, which was centred at Baphuon.

It is in an area of Cambodia where there is an important group of

ancient structures. It is the southernmost of Angkor’s main sites.The initial design and construction of the temple took place in the first half of the 12th century, during the reign of Suryavarman II (ruled 1113 – c. 1150). Dedicated to Vishnu, it was built as the king’s state temple and capital city. As neither the foundation stela

nor any contemporary inscriptions referring to the temple have been

found, its original name is unknown, but it may have been known as Vrah Vishnu-lok ( literally “Holy Vishnu’-Location’”, Old Khmer’ Cl. Sanskrit). after the presiding deity. Work seems to have ended shortly after the king’s death, leaving some of the bas-relief decoration unfinished.[5] In 1177, approximately 27 years after the death of Suryavarman II, Angkor was sacked by the Chams, the traditional enemies of the Khmer. Thereafter the empire was restored by a new king, Jayavarman VII, who established a new capital and state temple (Angkor Thom and the Bayon respectively) a few kilometres to the north.In the late 13th century, Angkor Wat gradually moved from Hindu to Theravada Buddhist

use, which continues to the present day. Angkor Wat is unusual among

the Angkor temples in that although it was somewhat neglected after the

16th century it was never completely abandoned, its preservation being

due in part to the fact that its moat also provided some protection from

encroachment by the jungle.[6]One of the first Western visitors to the temple was António da Madalena, a Portuguese

monk who visited in 1586 and said that it “is of such extraordinary

construction that it is not possible to describe it with a pen,

particularly since it is like no other building in the world. It has

towers and decoration and all the refinements which the human genius can

conceive of.”[7] In the mid 19th century the temple was visited by the French naturalist and explorer, Henri Mouhot, who popularised the site in the West through the publication of travel notes, in which he wrote:“One of these temples—a rival to that of Solomon, and erected by some ancient Michelangelo—might take an honourable place beside our most beautiful buildings. It is grander than anything left to us by Greece or Rome, and presents a sad contrast to the state of barbarism in which the nation is now plunged.”[8]

Mouhot, like other early Western visitors, found it difficult to

believe that the Khmers could have built the temple, and mistakenly

dated it to around the same era as Rome. The true history of Angkor Wat

was pieced together only from stylistic and epigraphic

evidence accumulated during the subsequent clearing and restoration

work carried out across the whole Angkor site. There were no ordinary

dwellings or houses or other signs of settlement including cooking

utensils, weapons, or items of clothing usually found at ancient sites.

Instead there is the evidence of the monuments themselves.[9]Facade of Angkor Wat, a drawing by Henri Mouhot Angkor Wat required considerable restoration in the 20th century, mainly the removal of accumulated earth and vegetation.[10] Work was interrupted by the civil war and Khmer Rouge

control of the country during the 1970s and 1980s, but relatively

little damage was done during this period other than the theft and

destruction of mostly post-Angkorian statues.[11]The temple is a powerful symbol of Cambodia, and is a source of great

national pride that has factored into Cambodia’s diplomatic relations

with France, the United States and its neighbour Thailand. A depiction

of Angkor Wat has been a part of Cambodian national flags since the introduction of the first version circa 1863.[12]

From a larger historical and even transcultural perspective, however,

the temple of Angkor Wat did not became a symbol of national pride sui

generis but had been inscribed into a larger politico-cultural process

of French-colonial heritage production in which the original temple site

was presented in French colonial and universal exhibitions in Paris and

Marseille between 1889 and 1937.[13]The splendid artistic legacy of Angkor Wat and other Khmer monuments in the Angkor region led directly to France adopting Cambodia as a protectorate

on 11 August 1863 and invading Siam to take control of the ruins. This

quickly led to Cambodia reclaiming lands in the northwestern corner of

the country that had been under Siamese (Thai) control since 1351 AD

(Manich Jumsai 2001), or by some accounts, 1431 AD.[14] Cambodia gained independence from France on 9 November 1953 and has controlled Angkor Wat since that time.During the midst of the Vietnam War, Chief of State Norodom Sihanouk hosted Jacqueline Kennedy in Cambodia to fulfill her “lifelong dream of seeing Angkor Wat.”[15]

In January 2003 riots erupted in Phnom Penh when a false rumour circulated that a Thai soap opera actress had claimed that Angkor Wat belonged to Thailand.[16]

Architecture

Site and plan

Angkor Wat, located at 13°24′45″N 103°52′0″E, is a unique combination of the temple mountain, the standard design for the empire’s state temples, the later plan of concentric galleries, and influences from Orissa and the Chola of Tamil Nadu, India. The temple is a representation of Mount Meru, the home of the gods: the central quincunx of towers symbolises the five peaks of the mountain, and the walls and moat the surrounding mountain ranges and ocean.[17]

Access to the upper areas of the temple was progressively more

exclusive, with the laity being admitted only to the lowest level.[18]Unlike most Khmer temples, Angkor Wat is oriented to the west rather than the east. This has led many (including Glaize and George Coedès) to conclude that Suryavarman intended it to serve as his funerary temple.[19] Further evidence for this view is provided by the bas-reliefs, which proceed in a counter-clockwise direction—prasavya

in Hindu terminology—as this is the reverse of the normal order.

Rituals take place in reverse order during Brahminic funeral services.[10] The archaeologist Charles Higham also describes a container which may have been a funerary jar which was recovered from the central tower.[20] It has been nominated by some as the greatest expenditure of energy on the disposal of a corpse.[21]

Freeman and Jacques, however, note that several other temples of Angkor

depart from the typical eastern orientation, and suggest that Angkor

Wat’s alignment was due to its dedication to Vishnu, who was associated

with the west.[17]A further interpretation of Angkor Wat has been proposed by Eleanor Mannikka.

Drawing on the temple’s alignment and dimensions, and on the content

and arrangement of the bas-reliefs, she argues that the structure

represents a claimed new era of peace under King Suryavarman II:

“as the measurements of solar and lunar time cycles were built into the

sacred space of Angkor Wat, this divine mandate to rule was anchored to

consecrated chambers and corridors meant to perpetuate the king’s power

and to honor and placate the deities manifest in the heavens above.”[22][23] Mannikka’s suggestions have been received with a mixture of interest and scepticism in academic circles.[20] She distances herself from the speculations of others, such as Graham Hancock, that Angkor Wat is part of a representation of the constellation Draco.[24]Style

Angkor Wat is the prime example of the classical style of Khmer architecture—the Angkor Wat style—to which it has given its name. By the 12th century Khmer architects had become skilled and confident in the use of sandstone (rather than brick or laterite)

as the main building material. Most of the visible areas are of

sandstone blocks, while laterite was used for the outer wall and for

hidden structural parts. The binding agent used to join the blocks is

yet to be identified, although natural resins or slaked lime have been suggested.[25]Angkor Wat has drawn praise above all for the harmony of its design, which has been compared to the architecture of ancient Greece and Rome. According to Maurice Glaize,

a mid-20th-century conservator of Angkor, the temple “attains a classic

perfection by the restrained monumentality of its finely balanced

elements and the precise arrangement of its proportions. It is a work of

power, unity and style.”[26]Architecturally, the elements characteristic of the style include: the ogival, redented towers shaped like lotus buds; half-galleries

to broaden passageways; axial galleries connecting enclosures; and the

cruciform terraces which appear along the main axis of the temple.

Typical decorative elements are devatas (or apsaras), bas-reliefs, and on pediments

extensive garlands and narrative scenes. The statuary of Angkor Wat is

considered conservative, being more static and less graceful than

earlier work.[27] Other elements of the design have been destroyed by looting and the passage of time, including gilded stucco on the towers, gilding on some figures on the bas-reliefs, and wooden ceiling panels and doors.[28]The Angkor Wat style was followed by that of the Bayon period, in which quality was often sacrificed to quantity.[29] Other temples in the style are Banteay Samré, Thommanon, Chao Say Tevoda and the early temples of Preah Pithu at Angkor; outside Angkor, Beng Mealea and parts of Phanom Rung and Phimai.

Features

Outer enclosure

The outer wall, 1024 by 802 m and 4.5 m high, is surrounded by a 30 m

apron of open ground and a moat 190 m wide. Access to the temple is by

an earth bank to the east and a sandstone causeway to the west; the

latter, the main entrance, is a later addition, possibly replacing a

wooden bridge.[30] There are gopuras at each of the cardinal points;

the western is by far the largest and has three ruined towers. Glaize

notes that this gopura both hides and echoes the form of the temple

proper.[31] Under the southern tower is a statue of Vishnu, known as Ta Reach, which may originally have occupied the temple’s central shrine.[30]

Galleries run between the towers and as far as two further entrances on

either side of the gopura often referred to as “elephant gates”, as

they are large enough to admit those animals. These galleries have

square pillars on the outer (west) side and a closed wall on the inner

(east) side. The ceiling between the pillars is decorated with lotus

rosettes; the west face of the wall with dancing figures; and the east

face of the wall with balustered windows, dancing male figures on

prancing animals, and devatas, including (south of the entrance) the only one in the temple to be showing her teeth.The outer wall encloses a space of 820,000 square metres (203 acres),

which besides the temple proper was originally occupied by the city

and, to the north of the temple, the royal palace. Like all secular

buildings of Angkor, these were built of perishable materials rather

than of stone, so nothing remains of them except the outlines of some of

the streets.[32] Most of the area is now covered by forest. A 350 m causeway connects the western gopura to the temple proper, with naga balustrades and six sets of steps leading down to the city on either side. Each side also features a library

with entrances at each cardinal point, in front of the third set of

stairs from the entrance, and a pond between the library and the temple

itself. The ponds are later additions to the design, as is the cruciform

terrace guarded by lions connecting the causeway to the central

structure.[32]Central structure

The temple stands on a terrace raised higher than the city. It is made of three rectangular galleries

rising to a central tower, each level higher than the last. Mannikka

interprets these galleries as being dedicated to the king, Brahma, the moon, and Vishnu.[5] Each gallery has a gopura at each of the points, and the two inner galleries each have towers at their corners, forming a quincunx

with the central tower. Because the temple faces west, the features are

all set back towards the east, leaving more space to be filled in each

enclosure and gallery on the west side; for the same reason the

west-facing steps are shallower than those on the other sides.The outer gallery measures 187 by 215 m, with pavilions rather than

towers at the corners. The gallery is open to the outside of the temple,

with columned half-galleries extending and buttressing the structure.

Connecting the outer gallery to the second enclosure on the west side is

a cruciform cloister called Preah Poan (the “Hall of a Thousand Gods”). Buddha

images were left in the cloister by pilgrims over the centuries,

although most have now been removed. This area has many inscriptions

relating the good deeds of pilgrims, most written in Khmer but others in Burmese and Japanese. The four small courtyards marked out by the cloister may originally have been filled with water.[33] North and south of the cloister are libraries.Beyond, the second and inner galleries are connected to each other

and to two flanking libraries by another cruciform terrace, again a

later addition. From the second level upwards, devatas

abound on the walls, singly or in groups of up to four. The

second-level enclosure is 100 by 115 m, and may originally have been

flooded to represent the ocean around Mount Meru.[34]

Three sets of steps on each side lead up to the corner towers and

gopuras of the inner gallery. The very steep stairways represent the

difficulty of ascending to the kingdom of the gods.[35] This inner gallery, called the Bakan,

is a 60 m square with axial galleries connecting each gopura with the

central shrine, and subsidiary shrines located below the corner towers.

The roofings of the galleries are decorated with the motif of the body

of a snake ending in the heads of lions or garudas. Carved lintels and pediments

decorate the entrances to the galleries and to the shrines. The tower

above the central shrine rises 43 m to a height of 65 m above the

ground; unlike those of previous temple mountains, the central tower is

raised above the surrounding four.[36]

The shrine itself, originally occupied by a statue of Vishnu and open

on each side, was walled in when the temple was converted to Theravada Buddhism,

the new walls featuring standing Buddhas. In 1934, the conservator

George Trouvé excavated the pit beneath the central shrine: filled with

sand and water it had already been robbed of its treasure, but he did

find a sacred foundation deposit of gold leaf two metres above ground level.[37]Decoration

Devatas are characteristic of the Angkor Wat style.

Integrated with the architecture of the building, and one of the

causes for its fame is Angkor Wat’s extensive decoration, which

predominantly takes the form of bas-relief

friezes. The inner walls of the outer gallery bear a series of

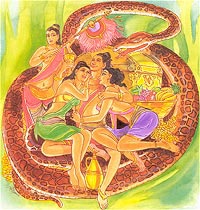

large-scale scenes mainly depicting episodes from the Hindu epics the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Higham has called these, “the greatest known linear arrangement of stone carving”.[38] From the north-west corner anti-clockwise, the western gallery shows the Battle of Lanka (from the Ramayana, in which Rama defeats Ravana) and the Battle of Kurukshetra (from the Mahabharata, showing the mutual annihilation of the Kaurava and Pandava clans). On the southern gallery follow the only historical scene, a procession of Suryavarman II, then the 32 hells and 37 heavens of Hindu mythology.On the eastern gallery is one of the most celebrated scenes, the Churning of the Sea of Milk, showing 92[39] asuras and 88 devas using the serpent Vasuki

to churn the sea under Vishnu’s direction (Mannikka counts only 91

asuras, and explains the asymmetrical numbers as representing the number

of days from the winter solstice to the spring equinox, and from the equinox to the summer solstice).[40] It is followed by Vishnu defeating asuras (a 16th-century addition). The northern gallery shows Krishna’s victory over Bana (where according to Glaize, “The workmanship is at its worst”[41])

and a battle between the Hindu gods and asuras. The north-west and

south-west corner pavilions both feature much smaller-scale scenes, some

unidentified but most from the Ramayana or the life of Krishna.Construction techniques

The stones, as smooth as polished marble, were laid without mortar

with very tight joints that were sometimes hard to find. The blocks were

held together by mortise and tenon

joints in some cases, while in others they used dovetails and gravity.

The blocks were presumably put in place by a combination of elephants, coir

ropes, pulleys and bamboo scaffolding. Henri Mouhot noted that most of

the blocks had holes 2.5 cm in diameter and 3 cm deep, with more holes

on the larger blocks. Some scholars have suggested that these were used

to join them together with iron rods, but others claim they were used to

hold temporary pegs to help manoeuvre them into place.The monument was made out of enormous amounts of sandstone, as much

as Khafre’s pyramid in Egypt (over 5 million tons). This sandstone had

to be transported from Mount Kulen, a quarry approximately 25 miles

(40 km) to the northeast. The stone was presumably transported by raft

along the Siem Reap river. This would have to have been done with care

to avoid overturning the rafts with such a large amount of weight. One

modern engineer estimated it would take 300 years to complete Angkor Wat

today.[42]

Yet the monument was begun soon after Suryavarman came to the throne

and was finished shortly after his death, no more than 40 years.Virtually all of its surfaces, columns, lintels even roofs are carved. There are miles of reliefs illustrating scenes from Indian literature

including unicorns, griffins, winged dragons pulling chariots as well

as warriors following an elephant-mounted leader and celestial dancing

girls with elaborate hair styles. The gallery wall alone is decorated

with almost 1,000 square metres of bas reliefs. Holes on some of the

Angkor walls indicate that they may have been decorated with bronze

sheets. These were highly prized in ancient times and were a prime

target for robbers. While excavating Khajuraho, Alex Evans, a stonemason

and sculptor, recreated a stone sculpture under 4 feet (1.2 m), this

took about 60 days to carve.[43]

Roger Hopkins and Mark Lehner also conducted experiments to quarry

limestone which took 12 quarrymen 22 days to quarry about 400 tons of

stone.[44]

The labour force to quarry, transport, carve and install so much

sandstone must have run into the thousands including many highly skilled

artisans. The skills required to carve these sculptures were developed

hundreds of years earlier, as demonstrated by some artifacts that have

been dated to the seventh century, before the Khmer came to power.[21][42]…Angkor Wat today

World Monuments Fund video on conservation of Angkor Wat

The Archaeological Survey of India carried out restoration work on the temple between 1986 and 1992.[45]

Since the 1990s, Angkor Wat has seen continued conservation efforts and

a massive increase in tourism. The temple is part of the Angkor World Heritage Site, established in 1992, which has provided some funding and has encouraged the Cambodian government to protect the site.[46] The German Apsara Conservation Project (GACP) is working to protect the devatas

and other bas-reliefs which decorate the temple from damage. The

organisation’s survey found that around 20% of the devatas were in very

poor condition, mainly because of natural erosion and deterioration of

the stone but in part also due to earlier restoration efforts.[47]

Other work involves the repair of collapsed sections of the structure,

and prevention of further collapse: the west facade of the upper level,

for example, has been buttressed by scaffolding since 2002,[48] while a Japanese team completed restoration of the north library of the outer enclosure in 2005.[49] World Monuments Fund began work on the Churning of the Sea of Milk Gallery in 2008.Angkor Wat has become a major tourist destination. In 2004 and 2005,

government figures suggest that, respectively, 561,000 and 677,000

foreign visitors arrived in Siem Reap province, approximately 50% of all

foreign tourists in Cambodia for both years.[50] The site has been managed by the private SOKIMEX

group since 1990, which rented it from the Cambodian government. The

influx of tourists has so far caused relatively little damage, other

than some graffiti;

ropes and wooden steps have been introduced to protect the bas-reliefs

and floors, respectively. Tourism has also provided some additional

funds for maintenance—as of 2000 approximately 28% of ticket revenues

across the whole Angkor

site was spent on the temples—although most work is carried out by

foreign government-sponsored teams rather than by the Cambodian

authorities.[51]At the ASEAN Tourism Forum 2012, both parties have agreed Borobudur

and Angkor Wat to become sister sites and the provinces will become

sister provinces. Two Indonesian airlines are considering the

opportunity to open a direct flight from Yogyakarta, Indonesia to Siem Reap.[52]

• Bayon

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bayon

| Bayon | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| Coordinates: | 13°26′28″N 103°51′31″ECoordinates: 13°26′28″N 103°51′31″E |

| Name | |

| Proper name: | Prasat Bayon |

| Location | |

| Country: | Cambodia |

| Location: | Angkor Thom |

| Architecture and culture | |

| Primary deity: | Buddha, Avalokiteshvara |

| Architectural styles: | Khmer |

| History | |

| Date built: (Current structure) |

end of 12th c. CE |

| Creator: | Jayavarman VII |

According to Angkor-scholar Maurice Glaize, the Bayon appears “as but a muddle of stones, a sort of moving chaos assaulting the sky.”[1]

From the vantage point of the temple’s upper terrace, one is struck by “the serenity of the stone faces” occupying many towers.[1]

The Bayon (Khmer: ប្រាសាទបាយ័ន, Prasat Bayon) is a well-known and richly decorated Khmer temple at Angkor in Cambodia. Built in the late 12th century or early 13th century as the official state temple of the Mahayana Buddhist King Jayavarman VII, the Bayon stands at the centre of Jayavarman’s capital, Angkor Thom. Following Jayavarman’s death, it was modified and augmented by later Hindu and Theravada Buddhist kings in accordance with their own religious preferences.

The Bayon’s most distinctive feature is the multitude of serene and

massive stone faces on the many towers which jut out from the upper

terrace and cluster around its central peak.[2] The temple is known also for two impressive sets of bas-reliefs, which present an unusual combination of mythological, historical, and mundane scenes. The current main conservatory body, the Japanese Government team for the Safeguarding of Angkor (the JSA) has described the temple as “the most striking expression of the baroque style” of Khmer architecture, as contrasted with the classical style of Angkor Wat.[3]

Contents |

History

Buddhist symbolism in the foundation of the temple by King Jayavarman VII

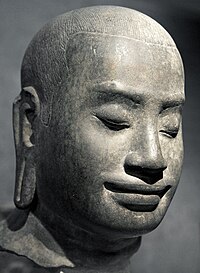

According to scholars, King Jayavarman VII bears a strong resemblance to the face towers of the Bayon.

The Bayon was the last state temple to be built at Angkor, and the only Angkorian state temple to be built primarily as a Mahayana Buddhist shrine dedicated to the Buddha,

though a great number of minor and local deities were also encompassed

as representatives of the various districts and cities of the realm. It

was the centrepiece of Jayavarman VII’s massive program of monumental construction and public works, which was also responsible for the walls and nāga-bridges of Angkor Thom and the temples of Preah Khan, Ta Prohm and Banteay Kdei.

The similarity of the 216 gigantic faces on the temple’s towers to

other statues of the king has led many scholars to the conclusion that

the faces are representations of Jayavarman VII himself. Others have said that the faces belong to the bodhisattva of compassion called Avalokitesvara or Lokesvara.[4] The two hypotheses need not be regarded as mutually exclusive. Angkor scholar George Coedès

has theorized that Jayavarman stood squarely in the tradition of the

Khmer monarchs in thinking of himself as a “devaraja” (god-king), the

salient difference being that while his predecessors were Hindus and

regarded themselves as consubstantial with Shiva and his symbol the lingam, Jayavarman as a Buddhist identified himself with the Buddha and the bodhisattva.[5]

Alterations following the death of Jayavarman VII

Since the time of Jayavarman VII, the Bayon has suffered numerous additions and alterations at the hands of subsequent monarchs.[1] During the reign of Jayavarman VIII in the mid-13th century, the Khmer empire reverted to Hinduism and its state temple was altered accordingly. In later centuries, Theravada Buddhism

became the dominant religion, leading to still further changes, before

the temple was eventually abandoned to the jungle. Current features

which were not part of the original plan include the terrace to the east

of the temple, the libraries, the square corners of the inner gallery, and parts of the upper terrace.

Modern restoration

In the first part of the 20th century, the École Française d’Extrême Orient took the lead in the conservation of the temple, restoring it in accordance with the technique of anastylosis.

Since 1995 the Japanese Government team for the Safeguarding of Angkor

(the JSA) has been the main conservatory body, and has held annual

symposia.

The site

The temple is oriented towards the east, and so its buildings are set

back to the west inside enclosures elongated along the east-west axis.

Because the temple sits at the exact centre of Angkor Thom, roads lead to it directly from the gates at each of the city’s cardinal points. The temple itself has no wall or moats,

these being replaced by those of the city itself: the city-temple

arrangement, with an area of 9 square kilometres, is much larger than

that of Angkor Wat

to the south (2 km²). Within the temple itself, there are two galleried

enclosures (the third and second enclosures) and an upper terrace (the

first enclosure). All of these elements are crowded against each other

with little space between. Unlike Angkor Wat,

which impresses with the grand scale of its architecture and open

spaces, the Bayon “gives the impression of being compressed within a

frame which is too tight for it.”[6]

The outer gallery: historical events and everyday life

The outer wall of the outer gallery features a series of bas-reliefs

depicting historical events and scenes from the everyday life of the

Angkorian Khmer. Though highly detailed and informative in themselves,

the bas-reliefs are not accompanied by any sort of epigraphic text, and

for that reason considerable uncertainty remains as to which historical

events are portrayed and how, if at all, the different reliefs are

related.[7] From the east gopura clockwise, the subjects are:

- in the southern part of the eastern gallery a marching Khmer army (including some Chinese soldiers),[8] with musicians, horsemen, and officers mounted on elephants, followed by wagons of provisions;

- still in the eastern gallery, on the other side of the doorway

leading into the courtyard, another procession followed by domestic

scenes depicting Angkorian houses, some of the occupants of which appear

to be Chinese merchants; - in the southeast corner pavilion, an unfinished temple scene with towers, apsaras, and a lingam;

- in the eastern part of the southern gallery, a naval battle on the Tonle Sap between Khmer and Cham forces,[9]

underneath which are more scenes from civilian life depicting a market,

open-air cooking, hunters, and women tending to children and an

invalid; - still in the southern gallery, past the doorway leading to the

courtyard, a scene with boats and fisherman, including a Chinese junk,

below which is a depiction of a cockfight;

then some palace scenes with princesses, servants, people engaged in

conversations and games, wrestlers, and a wild boar fight; then a battle

scene with Cham warriors disembarking from boats and engaging Khmer

warriors whose bodies are protected by coiled ropes, followed by a scene

in which the Khmer dominate the combat, followed by a scene in which

the Khmer king celebrates a victory feast with his subjects; - in the western part of the southern gallery, a military procession

including both Khmers and Chams, elephants, war machines such as a large

crossbow and a catapult; - in the southern part of the western gallery, unfinished reliefs show

an army marching through the forest, then arguments and fighting

between groups of Khmers;[10] - in the western gallery, past the doorway to the courtyard, a scene

depicting a melee between Khmer warriors, then a scene in which warriors

pursue others past a pool in which an enormous fish swallows a small

deer;[11] then a royal procession, with the king standing on an elephant, preceded by the ark of the sacred flame; - in the western part of the northern gallery, again unfinished, a

scene of royal entertainment including athletes, jugglers and acrobats, a

procession of animals, ascetics sitting in a forest, and more battles

between Khmer and Cham forces; - in the northern gallery, past the doorway to the courtyard, a scene

in which the Khmer flee from Cham soldiers advancing in tight ranks; - in the northeast corner pavilion, another marching Khmer army;

- in the eastern gallery, a land battle between Khmer and Cham forces,

both of which are supported by elephants: the Khmer appear to be

winning.

The outer gallery encloses a courtyard in which there are two

libraries (one on either side of the east entrance). Originally the

courtyard contained 16 chapels, but these were subsequently demolished

by the Hindu restorationist Jayavarman VIII.

The inner gallery: depictions of mythological events

The inner gallery is raised above ground level and has doubled

corners, with the original redented cross-shape later filled out to a

square. Its bas-reliefs, later additions of Jayavarman VIII, are in

stark contrast to those of the outer: rather than set-piece battles and

processions, the smaller canvases offered by the inner gallery are

decorated for the most part with scenes from Hindu mythology. Some of the figures depicted are Siva, Vishnu, and Brahma, the members of the trimurti or threefold godhead of Hinduism, Apsaras or celestial dancers, Ravana and Garuda.[12]

There is however no certainty as to what some of the panels depict, or

as to their relationship with one another. One gallery just north of the

eastern gopura,

for example, shows two linked scenes which have been explained as the

freeing of a goddess from inside a mountain, or as an act of iconoclasm

by Cham invaders.[13]

Another series of panels shows a king fighting a gigantic serpent with

his bare hands, then having his hands examined by women, and finally

lying ill in bed; these images have been connected with the legend of

the Leper King, who contracted leprosy from the venom of a serpent with

whom he had done battle.[14] Less obscure are depictions of the construction of a Vishnuite temple (south of the western gopura) and the Churning of the Sea of Milk (north of the western gopura).

The upper terrace: 200 faces of Lokesvara

The inner gallery is nearly filled by the upper terrace, raised one

level higher again. The lack of space between the inner gallery and the

upper terrace has led scholars to conclude that the upper terrace did

not figure in the original plan for the temple, but that it was added

shortly thereafter following a change in design. Originally, it is

believed, the Bayon had been designed as a single-level structure,

similar in that respect to the roughly contemporaneous foundations at Ta Prohm and Banteay Kdei.[15]

The upper terrace is home to the famous “face towers” of the Bayon,

each of which supports two, three or (most commonly) four gigantic

smiling faces. In addition to the mass of the central tower, smaller

towers are located along the inner gallery (at the corners and

entrances), and on chapels on the upper terrace. “Wherever one wanders,”

writes Maurice Glaize, the faces of Lokesvara follow and dominate with their multiple presence.”[16]

Efforts to read some significance into the numbers of towers and

faces have run up against the circumstance that these numbers have not

remained constant over time, as towers have been added through

construction and lost to attrition. At one point, the temple was host to

49 such towers; now only 37 remain.[2] The number of faces is approximately 200, but since some are only partially preserved there can be no definitive count.

The central tower and sanctuary

Like the inner gallery, the central tower was originally cruciform

but was later filled out and made circular. It rises 43 metres above the

ground. At the time of the temple’s foundation, the principal religious

image was a statue of the Buddha, 3.6 m tall, located in the sanctuary

at the heart of the central tower. The statue depicted the Buddha

seated in meditation, shielded from the elements by the flared hood of

the serpent king Mucalinda. During the reign of Hindu restorationist monarch Jayavarman VIII,

the figure was removed from the sanctuary and smashed to pieces. After

being recovered in 1933 from the bottom of a well, it was pieced back

together, and is now on display in a small pavilion at Angkor.[17]

Images of the Bayon

|

|

|

|

• Krol Ko

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Krol_Ko

Krol Ko at Angkor, Cambodia, is a Buddhist temple built at the end of the 12th century under the rule of Jayavarman VII. It is north of Neak Pean.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

Coordinates: 13°28′5″N 103°53′42″E

| This article about a building or structure in Cambodia is a stub. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it. |

| This article about a Buddhist monastery, temple or nunnery is a stub. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it. |

| Kingdom of Cambodia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: Nation, Religion, King |

||||||

| Anthem: Nokor Reach Majestic Kingdom |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) |

Phnom Penh 11°33′N 104°55′E |

|||||

| Official language(s) | Khmer | |||||

| Official script | Khmer script | |||||

| Ethnic groups | 90.0% Khmer 5.0% Vietnamese 1.0% Chinese 4.0% other |

|||||

| Demonym | Khmer or Cambodian | |||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy | |||||

| - | King | Norodom Sihamoni | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Hun Sen (CPP) | ||||

| - | Senate President | Chea Sim (CPP) | ||||

| - | President of National Assembly | Heng Samrin (CPP) | ||||

| Legislature | Parliament | |||||

| - | Upper house | Senate | ||||

| - | Lower house | National Assembly | ||||

| Formation | ||||||

| - | Funan Kingdom | 68 | ||||

| - | Chenla Kingdom | 550 | ||||

| - | Khmer Empire | 802 | ||||

| - | French Colonization | 1863 | ||||

| - | Independence from France | November 9, 1953 | ||||

| - | Monarchy Restored | September 24, 1993 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 181,035 km2 (88th) 69,898 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 2.5 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2010 estimate | 14,138,000[1] (65th) | ||||

| - | 2008 census | 13,388,910[2] | ||||

| - | Density | 81.8/km2 (118th) 211.8/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2012 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $36.010 billion[3] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $2,361[3] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2012 (est.) estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $14.204 billion[3] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $931[3] | ||||

| Gini (2007) | 43[4] (medium) | |||||

| HDI (2011) | ||||||

| Currency | Riel (KHR) |

|||||

| Time zone | (UTC+7) | |||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | KH | |||||

| Internet TLD | .kh | |||||

| Calling code | +855 | |||||

| 1 | The US Dollar is often used | |||||

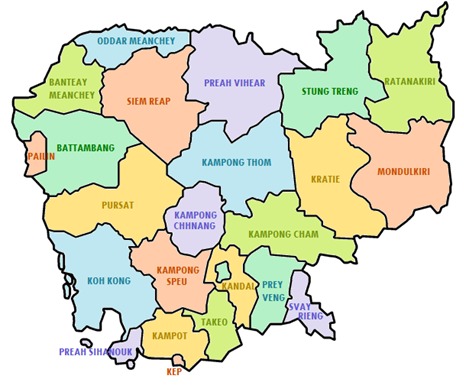

Cambodia (![]() i/kæmˈboʊdiə/;[6] Khmer: ព្រះរាជាណាចក្រកម្ពុជា, Kampuchea, IPA: [kɑmˈpuˈciə]), officially known as the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochina Peninsula in Southeast Asia. With a total landmass of 181,035 square kilometres (69,898 sq mi), it is bordered by Thailand to the northwest, Laos to the northeast, Vietnam to the east, and the Gulf of Thailand to the southwest.

i/kæmˈboʊdiə/;[6] Khmer: ព្រះរាជាណាចក្រកម្ពុជា, Kampuchea, IPA: [kɑmˈpuˈciə]), officially known as the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochina Peninsula in Southeast Asia. With a total landmass of 181,035 square kilometres (69,898 sq mi), it is bordered by Thailand to the northwest, Laos to the northeast, Vietnam to the east, and the Gulf of Thailand to the southwest.

With a population of over 14.8 million, Cambodia is the 68th most populous country in the world. The official religion is Theravada Buddhism, which is practiced by approximately 95% of the Cambodian population. The country’s minority groups include Vietnamese, Chinese, Chams and 30 various hill tribes.[7] The capital and largest city is Phnom Penh; the political, economic, and cultural center of Cambodia. The kingdom is a constitutional monarchy with Norodom Sihamoni, a monarch chosen by the Royal Throne Council, as head of state. The head of government is Hun Sen, who is currently the longest serving leader in South East Asia and has ruled Cambodia for over 25 years.

In 802 AD Jayavarman II declared himself king marking the beginning of the Khmer Empire

which flourished for over 600 years and allowing successive kings to

dominate much of Southeast Asia and accumulate immense power and wealth.

The Indianized kingdom built monumental temples such as Angkor Wat and facilitated the spread of first Hinduism, then Buddhism to much of Southeast Asia. After the fall of Angkor to Ayutthaya

in the 15th century, Cambodia was ruled as a vassal between its

neighbors until it was colonized by the French in the mid-19th century.

Cambodia gained independence in 1953.

The Vietnam War extended into Cambodia, giving rise to the Khmer Rouge, which took Phnom Penh in 1975. Cambodia reemerged several years later within a socialistic sphere of influence as the People’s Republic of Kampuchea

until 1993. After years of isolation, the war-ravaged nation was

reunited under the monarchy in 1993 and has seen rapid progress in the

economic and human resource areas while rebuilding from decades of civil war.

Cambodia has had one of the best economic records in Asia, with

economic growth averaging 6.0% for the last 10 years. Strong textiles,

agriculture, construction, garments, and tourism sectors led to foreign

investments and international trade.[8]

In 2005, oil and natural gas deposits were found beneath Cambodia’s

territorial waters, and once commercial extraction begins in 2013, the

oil revenues could profoundly affect Cambodia’s economy.[9]

Contents |

Name

The official name of the country in English is the “Kingdom of Cambodia”, translated from the Khmer “/preăh riəchiənaːchaʔ kampuciə/“, often shortened to just “Kampuchea” (Khmer: កម្ពុជា). Colloquially, Cambodians most often refer to their country as ស្រុកខ្មែរ (Khmer pronunciation: [srok kʰmae], Srok Khmer), meaning “The Land of the Khmers” or by using the slightly more formal form ប្រទេសកម្ពុជា (Khmer pronunciation: [prɑteːh kampuciə], Prateh Kampuchea),

literally “The Country of Cambodia”. The English form “Cambodia” is

derived from “Cambodge”, the French transcription of “Kampuchea”.

History

Pre-history

There is sparse evidence for a Pleistocene human occupation of present day Cambodia, which includes quartz and quartzite pebble tools found in terraces along the Mekong River, in Stung Treng and Kratié provinces, and in Kampot Province, although their dating is unreliable.[10]

Some slight archaeological evidence shows communities of hunter-gatherers inhabited Cambodia during Holocene: the most ancient Cambodian archeological site is considered to be the cave of L’aang Spean, in Battambang Province, which belongs to the Hoabinhian period. Excavations in its lower layers produced a series of radiocarbon dates as of 6000 BC.[10][11]

Upper layers in the same site gave evidence of transition to Neolithic, containing the earliest dated earthenware ceramics in Cambodia[12]

Archeological records for the period between Holocene and Iron Age remain equally limited. Other prehistoric sites of somewhat uncertain date are Samrong Sen (not far from the ancient capital of Udong), where the first investigations began in 1877,[13] and Phum Snay, in the northern province of Banteay Meanchey.[14] Prehistoric artifacts are often found during mining activities in Ratanakiri.[10]

The most curious prehistoric evidence in Cambodia however is the various “circular earthworks“, discovered in the red soils near Memot

and in the adjacent region of Vietnam in the latter 1950s. Their

function and age are still debated, but some of them possibly date from

2nd millennium BC at least.[15][16]

A pivotal event in Cambodian prehistory was the slow penetration of

the first rice farmers from the north, which began in the late 3rd

millennium BC.[17]

Iron was worked by about 500 BC, with supporting evidence coming from the Khorat Plateau, in modern day Thailand. In Cambodia, some Iron Age settlements were found beneath Baksei Chamkrong and other Angkorian temples while circular earthworks, were found beneath Lovea

a few kilometers north-west of Angkor. Burials, much richer than other

types of finds, testify to improvement of food availability and trade

(even on long distances: in the 4th century BC trade relations with

India were already opened) and the existence of a social structure and

labor organization.[17]

Pre-Angkorian era and Angkorian era

During the 3rd, 4th, and 5th centuries, the Indianized states of Funan and its successor, Chenla, coalesced in present-day Cambodia and southwestern Vietnam. For more than 2,000 years, Cambodia absorbed influences from India, passing them on to other Southeast Asian civilizations that are now Thailand and Laos.[18]

Little else is known for certain of these polities, however Chinese

chronicles and tribute records do make mention of them. The chronicles

suggest that after Jayavarman I of Chenla died around 690, turmoil

ensued which resulted in division of the kingdom into Land Chenla and

Water Chenla which was loosely ruled by weak princes under the dominion

of Java.

The Khmer Empire grew out of these remnants of Chenla becoming firmly established in 802 when Jayavarman II (reigned c790-850) declared independence from Java and proclaimed himself a Devaraja. He and his followers instituted the cult of the God-king and began a series of conquests that formed an empire which flourished in the area from the 9th to the 15th centuries.[19] Around the 13th century, monks from Sri Lanka introduced Theravada Buddhism to Southeast Asia.[20] The religion spread and eventually displaced Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism as the popular religion of Angkor.

The Khmer Empire was Southeast Asia’s largest empire during the 12th century. The empire’s center of power was Angkor,

where a series of capitals was constructed during the empire’s zenith.

In 2007 an international team of researchers using satellite photographs

and other modern techniques concluded that Angkor had been the largest

pre-industrial city in the world with an urban sprawl of 1,150 square

miles.[21] The city, which could have supported a population of up to one million people[22] and Angkor Wat,

the most well known and best-preserved religious temple at the site,

still serve as reminders of Cambodia’s past as a major regional power.

The empire, though in decline, remained a significant force in the

region until its fall in the 15th century.

Dark ages of Cambodia

The ancient city of Longvek

After a long series of wars with neighboring kingdoms, Angkor was sacked by the Ayutthaya Kingdom and abandoned in 1432 because of ecological failure and infrastructure breakdown.[23][24]

This led to a period of economic, social, and cultural stagnation when

the kingdom’s internal affairs came increasingly under the control of

its neighbors. By this time, the Khmer penchant for monument building

had ceased. Older faiths such as Mahayana Buddhism and the Hindu cult of the god-king had been supplanted by Theravada Buddhism for good.

The court moved the capital to Longvek where the kingdom sought to regain its glory through maritime trade. Portuguese and Spanish travelers described the city as a place of flourishing wealth and foreign trade.

The attempt was short-lived however, as continued wars with Ayutthaya

and the Vietnamese resulted in the loss of more territory and Longvek

being conquered and destroyed by King Naresuan the Great of Ayutthaya in 1594. A new Khmer capital was established at Udong south of Longvek in 1618, but its monarchs could survive only by entering into what amounted to alternating vassal

relationships with the Siamese and Vietnamese for the next three

centuries with only a few short-lived periods of relative independence.

In the nineteenth century a renewed struggle between Siam and Vietnam

for control of Cambodia resulted in a period when Vietnamese officials

attempted to force the Khmers to adopt Vietnamese customs. This led to several rebellions against the Vietnamese and appeals to Thailand for assistance. The Siamese–Vietnamese War (1841–1845) ended with an agreement to place the country under joint suzerainty. This later led to the signing of a treaty for French Protection of Cambodia by King Norodom I.

French colonization

In 1863, King Norodom, who had been installed by Thailand,[25]

sought the protection of France from the Thai and Vietnamese after

tensions grew between them. In 1867 the Thai king signed a treaty with

France, renouncing suzerainty over Cambodia in exchange for the control of Battambang and Siem Reap

provinces which officially became part of Thailand. The provinces were

ceded back to Cambodia by a border treaty between France and Thailand in

1906.

Cambodia continued as a protectorate of France from 1863 to 1953, administered as part of the colony of French Indochina, though occupied by the Japanese empire from 1941 to 1945.[26] Between 1874 and 1962, the total population increased from about 946,000 to 5.7 million.[27]

After King Norodom’s death in 1904, France manipulated the choice of

king, and Sisowath, Norodom’s brother, was placed on the throne. The

throne became vacant in 1941 with the death of Monivong, Sisowath’s son,

and France passed over Monivong’s son, Monireth, feeling he was too

independently minded. Instead, Norodom Sihanouk, a maternal grand-son of king Sisowath was enthroned. The French thought young Sihanouk would be easy to control.[26]

They were wrong, however, and under the reign of King Norodom Sihanouk,

Cambodia gained independence from France on November 9, 1953.[26]

Independence and Vietnam War

Cambodia became a constitutional monarchy under King Norodom Sihanouk. When French Indochina was given independence, Cambodia lost hope of regaining control over the Mekong Delta as it was awarded to Vietnam. Formerly part of the Khmer Empire, the area had been controlled by the Vietnamese since 1698 with King Chey Chettha II granting Vietnamese permission to settle in the area decades before.[28] This remains a diplomatic sticking point with over one million ethnic Khmers (the Khmer Krom)

still living in this region. The Khmer Rouge attempted invasions to

recover the territory which, in part, led to Vietnam’s invasion of

Cambodia and usurpation of the Khmer Rouge.

In 1955, Sihanouk abdicated in favor of his father in order to

participate in politics and was elected prime minister. Upon his

father’s death in 1960, Sihanouk again became head of state, taking the

title of prince. As the Vietnam War progressed, Sihanouk adopted an official policy of neutrality in the Cold War,

although he was widely considered to be sympathetic to the communist

cause. Sihanouk allowed the Vietnamese communists to use Cambodia as a

sanctuary and a supply route for their arms and other aid to their armed

forces fighting in South Vietnam. This policy was perceived as

humiliating by many Cambodians. In December 1967 Washington Post

journalist Stanley Karnow was told by Sihanouk that if the US wanted to

bomb the Vietnamese communist sanctuaries, he would not object, unless

Cambodians were killed.[29] The same message was conveyed to US President Johnson’s emissary Chester Bowles in January 1968.[30]

So the US had no real motivation to overthrow Sihanouk. However members

of the government and army, who resented Sihanouk’s ruling style as

well as his tilt away from the United States, did have such a

motivation. While visiting Beijing in 1970 Sihanouk was ousted by a military coup led by Prime Minister General Lon Nol and Prince Sisowath Sirik Matak.

There is no evidence of any US role in the coup. However once the coup

was completed the new regime, which immediately demanded that the

Vietnamese communists leave Cambodia, gained the political support of

the United States. The North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces, desperate

to retain their sanctuaries and supply lines from North Vietnam,

immediately launched armed attacks on the new government. The king urged

his followers to help in overthrowing this government, hastening the

onset of civil war,[31] Soon the Khmer Rouge

rebels began using him to gain support. However from 1970 until early

1972 the Cambodian conflict was largely one between the government and

army of Cambodia, and the armed forces of North Vietnam. As they gained

control of Cambodian territory the Vietnamese communists imposed a new

political infrastructure, which was eventually dominated by the

Cambodian communists we now refer to as the Khmer Rouge.[32] So the Vietnamese communists played a vital role in the rise of the Khmer Rouge.

Norodom Sihanouk and Mao Tse-Tung in 1956

Between 1969 and 1973, Republic of Vietnam forces and U.S. forces bombed and briefly invaded Cambodia in an effort to disrupt the Viet Cong and Khmer Rouge.[33] Some two million Cambodians were made refugees

by the war and by the terrorist policies of the Khmer Rouge, and fled

to Phnom Penh. Estimates of the number of Cambodians killed during the

bombing campaigns vary widely, as do views of the effects of the

bombing. The U.S. Seventh Air Force argued that the bombing prevented

the fall of Phnom Penh in 1973 by killing 16,000 of 25,500 Khmer Rouge

fighters besieging the city.[34] However, journalist William Shawcross and Cambodia specialists Milton Osborne, David P. Chandler and Ben Kiernan argued that the bombing drove peasants to join the Khmer Rouge.[35]

Cambodia specialist Craig Etcheson argued that the Khmer Rouge “would

have won anyway”, even without U.S. intervention driving recruitment.[36] American diplomat Timothy M. Carney argued that the five reasons why Pol Pot won the war were: support from Sihanouk,

massive supplies of military aid from North Vietnam, government

corruption, the U.S. cut-off in air support after Watergate, and the

determination of the Cambodian Communists. Not one of them in his

opinion was the U.S. bombing.[37]

Khmer Republic (1970-1975)

| This section requires expansion. (July 2012) |

Khmer Rouge regime

As the Vietnam War ended, a draft USAID

report observed that the country faced famine in 1975, with 75% of its

draft animals destroyed, and that rice planting for the next harvest

would have to be done “by the hard labour of seriously malnourished

people”. The report predicted that

“Without large-scale external food and equipment assistance there

will be widespread starvation between now and next February … Slave

labour and starvation rations for half the nation’s people (probably

heaviest among those who supported the republic) will be a cruel

necessity for this year, and general deprivation and suffering will

stretch over the next two or three years before Cambodia can get back to

rice self-sufficiency”.[38]

Flag of the Khmer Rouge and Democratic Kampuchea

The Khmer Rouge reached Phnom Penh and took power in 1975. The regime, led by Pol Pot, changed the official name of the country to Democratic Kampuchea.

The regime modelled itself on Maoist China during the Great Leap

Forward. The regime immediately evacuated the cities and sent the entire

population on forced marches to rural work projects. They attempted to

rebuild the country’s agriculture on the model of the 11th century,

discarded Western medicine, and destroyed temples, libraries, and

anything considered Western. At least a million Cambodians, out of a

total population of 8 million, died from executions, overwork,

starvation and disease.[39]

Estimates as to how many people were killed by the Khmer Rouge regime

range from approximately one to three million; the most commonly cited

figure is two million (about one-third of the population).[40][41] This era gave rise to the term Killing Fields, and the prison Tuol Sleng

became notorious for its history of mass killing. Hundreds of thousands

fled across the border into neighbouring Thailand. The regime

disproportionately targeted ethnic minority groups. The Cham Muslims suffered serious purges with as much as half of their population exterminated.[42]

In the late 1960s, an estimated 425,000 ethnic Chinese

lived in Cambodia, but by 1984, due to Khmer Rouge killings and to

emigration, only about 61,400 Chinese remained in the country.[43] Forced repatriation in 1970 and deaths during the Khmer Rouge era reduced the Vietnamese population in Cambodia from between 250,000 and 300,000 in 1969 to a reported 56,000 in 1984.[27]

However most of the victims of the Khmer Rouge regime were not ethnic

minorities but ethnic Khmer. Professionals, such as doctors, lawyers and

teachers, were also targeted. According to Robert D. Kaplan, “eyeglasses were as deadly as the yellow star” as they were seen as a sign of intellectualism.[39]

Vietnamese occupation and transition

In November 1978, Vietnamese troops invaded Cambodia in response to border raids by the Khmer Rouge.[44] The People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK), a Pro-Soviet

state led by the Kampuchean People’s Revolutionary Party, a party

created by the Vietnamese in 1951, and led by a group of Khmer Rouge who

had fled Cambodia to avoid being purged by Pol Pot and Ta Mok, was

established.[45]

It was fully beholden to the occupying Vietnamese army and under

direction of the Vietnamese ambassador to Phnom Penh. Its arms came from

Vietnam and the Soviet Union. In opposition to the newly-created state,

a government-in-exile referred to as the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea (CGDK) was formed in 1981 from three factions. This consisted of the Khmer Rouge, a royalist faction led by Sihanouk, and the Khmer People’s National Liberation Front.

Its credentials were recognized by the United Nations. The Khmer Rouge

representative to the UN, Thiounn Prasith, was retained, but he had to

work in consultation with representatives of the noncommunist Cambodian

parties.[46][47]

Throughout the 1980s the CGDK, supplied by China, Thailand, the United States[48] and the United Kingdom[49][50]

controlled parts of the country and attacked some of the territory not

under their dominance. The refusal of Vietnam to withdraw from Cambodia

led to economic sanctions[51] by the U.S. and its allies, made reconstruction virtually impossible and left the country deeply impoverished.

Peace efforts began in Paris in 1989 under the State of Cambodia,

culminating two years later in October 1991 in a comprehensive peace

settlement. The UN was given a mandate to enforce a ceasefire and deal

with refugees and disarmament known as the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC).[52]

In 1993, Norodom Sihanouk was restored as King of Cambodia,

but all power was in the hands of the government established after the

UNTAC sponsored elections. The stability established following the

conflict was shaken in 1997 by a coup d’état led by the co-Prime

Minister Hun Sen against the noncommunist parties in the government.[53]

Many of the noncommunist politicians were murdered by Hun Sen’s forces.

In recent years, reconstruction efforts have progressed and led to some

political stability through political repression of a multiparty democracy under a constitutional monarchy.[54] In July 2010 Kang Kek Iew was the first Khmer Rouge member found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity in his role as the former commandant of the S21 extermination camp. He was sentenced to life in prison.[55][56] However Hun Sen has opposed any extensive trials of former Khmer Rouge mass murderers.[57]

He says that this is because he wishes to avoid political instability.

However it is more likely because of the prevalence of former Khmer

Rouge at the highest levels of Cambodia’s national and local government

structures.[citation needed]

Politics

Government

King Norodom Sihamoni

National politics in Cambodia take place within the framework of the nation’s constitution of 1993. The government is a constitutional monarchy operated as a parliamentary representative democracy. The Prime Minister of Cambodia, an office held by Hun Sen since 1985, is the head of government, while the King of Cambodia (currently Norodom Sihamoni) is the head of state. The prime minister is appointed by the king, on the advice and with the approval of the National Assembly

The prime minister and the ministerial appointees exercise executive power while legislative powers are shared by the executive and the bicameral Parliament of Cambodia, which consists of a lower house, the National Assembly or Radhsphea and an upper house, the Senate or Sénat. Members of the 123-seat Assembly are elected through a system of proportional representation

and serve for a maximum term of five years. The Senate has 58 seats,

two of which are appointed by the king and two others by the National

Assembly, and the rest elected by the commune councillors from 24 provinces of Cambodia. Senators serve five year terms.

On October 14, 2004, King Norodom Sihamoni

was selected by a special nine-member throne council, part of a

selection process that was quickly put in place after the abdication of

King Norodom Sihanouk a week prior. Sihamoni’s selection was endorsed by Prime Minister Hun Sen and National Assembly Speaker Prince Norodom Ranariddh

(the king’s half brother and current chief advisor), both members of

the throne council. He was enthroned in Phnom Penh on October 29, 2004.

The Cambodian People’s Party

(CPP) is the major ruling party in Cambodia. The CPP controls the lower

and upper chambers of parliament, with 73 seats in the National

Assembly and 43 seats in the Senate. The opposition Sam Rainsy Party is the second largest party in Cambodia with 26 seats in the National Assembly and 2 in the Senate.

Prime Minister Hun Sen.

Hun Sen and his government have seen much controversy. Hun Sen was a

former Khmer Rouge commander who was originally installed by the

Vietnamese and, after the Vietnamese left the country, maintains his strong man position by violence and oppression when deemed necessary.[58] In 1997, fearing the growing power of his co-Prime Minister, Prince Norodom Ranariddh, Hun launched a coup,

using the army to purge Ranariddh and his supporters. Ranariddh was

ousted and fled to Paris while other opponents of Hun Sen were arrested,

tortured and some summarily executed.[59][58]

In addition to political oppression, the Cambodian government has

been accused of corruption in the sale of vast areas of land to foreign

investors resulting in the eviction of thousands of villagers[60] as well as taking bribes in exchange for grants to exploit Cambodia’s oil wealth and mineral resources.[61] Cambodia is consistently listed as one of the most corrupt governments in the world.[62][63][64]

Military

Royal Cambodian Navy officers observe flight quarters during the Cambodia-US Maritime Exercise 2011.

The Royal Cambodian Army, Royal Cambodian Navy, Royal Cambodian Air Force and Royal Gendarmerie collectively form the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces, under the command of the Ministry of National Defense, presided over by the Prime Minister of Cambodia.

His Majesty King Norodom Sihamoni is the Supreme Commander of the Royal

Cambodian Armed Forces (RCAF), and the country’s Prime Minister Hun Sen

effectively holds the position of commander-in-chief.

The introduction of a revised command structure early in 2000 was a

key prelude to the reorganization of the Cambodian military. This saw

the defence ministry form three subordinate general departments

responsible for logistics and finance, materials and technical services,

and defence services under the High Command Headquarters (HCHQ).

The minister of National Defense is General Tea Banh. Banh has served as defense minister since 1979. The Secretaries of State for Defense are Chay Saing Yun

and Por Bun Sreu. The new Commander-in-Chief of the RCAF and was

replaced by his deputy General Pol Saroeun, who is a long time loyalist

of Prime Minister Hun Sen. The Army Commander is General Meas Sophea and the Army Chief of Staff is Chea Saran.

In 2010, the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces comprised about 210,000

personnel. Total Cambodian military spending stands at 3% of national

GDP. The Royal Gendarmerie of Cambodia total more than 7,000 personnel.

Its civil duties include providing security and public peace, to

investigate and prevent organized crime, terrorism and other violent

groups; to protect state and private property; to help and assist

civilians and other emergency forces in a case of emergency, natural

disaster, civil unrest and armed conflicts.

Foreign relations

Ambassador Thay Vanna presents his credentials to Russian President Dmitry Medvedev on October 18, 2010.

Foreign Minister Hor Nam Hong meets with U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in New York City in 2009.

The foreign relations of Cambodia are handled by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs under H.E. Hor Namhong.

Cambodia is a member of the United Nations, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. It is a member of the Asian Development Bank (ADB), ASEAN, and joined the WTO on October 13, 2004. In 2005 Cambodia attended the inaugural East Asia Summit in Malaysia. On November 23, 2009, Cambodia reinstated its membership to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).[65] Cambodia first became a member of IAEA on February 6, 1958 but withdrew its membership on March 26, 2003.[66] Cambodia has established diplomatic relations with numerous countries; the government reports twenty embassies in the country[67]

including many of its Asian neighbours and those of important players

during the Paris peace negotiations, including the US, Australia,

Canada, China, the European Union (EU), Japan, and Russia.[68] As a result of its international relations, various charitable organizations have assisted with social, economic, and civil infrastructure needs.

In recent years, bilateral relations between the United States and

Cambodia have strengthened. The U.S. supports efforts in Cambodia to

combat terrorism, build democratic institutions, promote human rights,

foster economic development, eliminate corruption, achieve the fullest

possible accounting for Americans missing from the Vietnam War-era,

and to bring to justice those most responsible for serious violations

of international humanitarian law committed under the Khmer Rouge

regime. China’s geopolitical interest in Cambodia changed significantly

with the end of the Cold War. It retains considerable influence,

including close links with former King Norodom Sihanouk,

senior members of Cambodian Government, and the ethnic Chinese

community in Cambodia. There are regular high level exchanges between

the two countries. Japan has been a vital contributor to Cambodia’s

rehabilitation and reconstruction since the high-profile UN Transitional Authority (UNTAC)

mission and elections in 1993. Japan provided some US$1.2 billion in

total overseas development assistance (ODA) during the period since 1992

and remains Cambodia’s top donor country.

While the violent ruptures of the 1970s and 80s have passed, several border disputes

between Cambodia and its neighbors persist. There are disagreements

over some offshore islands and sections of the boundary with Vietnam and

undefined maritime boundaries and border areas with Thailand. Both Cambodian and Thai troops have clashed over land immediately adjacent to the Preah Vihear temple, leading to a deterioration in relations. The International Court of Justice

in 1962 awarded the temple to Cambodia but was unclear regarding some

of the surrounding land. Both countries blamed the other for firing

first and denied entering the other’s territory.

International rankings

| Organization | Survey | Ranking | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transparency International | Corruption Perceptions Index(2012) | 164 Out of 184 | 89.13% |

| United Nations Development Programme | Human Development Index(2012) | 139 Out of 184 | 75.5% |

| World Gold Council | Gold reserve(2010) | 65 Out of 110 | 60% |

| Reporters Without Borders | Worldwide Press Freedom Index(2012) | 117 out of 179 | 65.3% |

| Heritage Foundation | Indices of Economic Freedom(2012) | 102 Out of 179 | 57% |

| Global Competitiveness Report | World Economic Forum(2012) | 97 out of 142 | 68.3% |

| Global Peace Index | Institute for Economics and Peace(2012) | 108 out of 142 | 68.3% |

| United Nations | Education Index(2012) | 132 out of 179 | 73.7% |

Geography

Phnom Dângrêk in Northern Cambodia

Cambodia has an area of 181,035 square kilometers (69,898 sq mi) and lies entirely within the tropics, between latitudes 10° and 15°N, and longitudes 102° and 108°E. It borders Thailand to the north and west, Laos to the northeast, and Vietnam to the east and southeast. It has a 443-kilometer (275 mi) coastline along the Gulf of Thailand.

Cambodia’s landscape is characterized by a low-lying central plain

that is surrounded by uplands and low mountains and includes the Tonle Sap (Great Lake) and the upper reaches of the Mekong River

delta. Extending outward from this central region are transitional

plains, thinly forested and rising to elevations of about 650 feet (200

meters) above sea level. To the north the Cambodian plain abuts a

sandstone escarpment, which forms a southward-facing cliff stretching

more than 200 miles (320 km) from west to east and rising abruptly above

the plain to heights of 600 to 1,800 feet (180 to 550 meters). This

escarpment marks the southern limit of the Dângrêk Mountains.

Flowing south through the country’s eastern regions is the Mekong

River. East of the Mekong the transitional plains gradually merge with

the eastern highlands, a region of forested mountains and high plateaus

that extend into Laos and Vietnam. In southwestern Cambodia two distinct

upland blocks, the Krâvanh Mountains and the Dâmrei Mountains, form another highland region that covers much of the land area between the Tonle Sap and the Gulf of Thailand. In this remote and largely uninhabited area, Phnom Aural,

Cambodia’s highest peak, rises to an elevation of 5,949 feet (1,813

meters). The southern coastal region adjoining the Gulf of Thailand is a

narrow lowland strip, heavily wooded and sparsely populated, which is

isolated from the central plain by the southwestern highlands.

The most distinctive geographical feature is the inundations of the

Tonle Sap (Great Lake), measuring about 2,590 square kilometers

(1,000 sq mi) during the dry season and expanding to about 24,605 square

kilometers (9,500 sq mi) during the rainy season. This densely

populated plain, which is devoted to wet rice cultivation, is the

heartland of Cambodia. Much of this area has been designated as a biosphere reserve.

Climate

Cambodia’s climate, like that of the rest of Southeast Asia, is dominated by monsoons, which are known as tropical wet and dry because of the distinctly marked seasonal differences.

Cambodia has a temperature range from 21 to 35 °C (69.8 to 95 °F) and

experiences tropical monsoons. Southwest monsoons blow inland bringing

moisture-laden winds from the Gulf of Thailand

and Indian Ocean from May to October. The northeast monsoon ushers in

the dry season, which lasts from November to March. The country

experiences the heaviest precipitation from September to October with

the driest period occurring from January to February.

Cambodia has two distinct seasons. The rainy season, which runs from May to October, can see temperatures drop to 22 °C (71.6 °F) and is generally accompanied with high humidity. The dry season lasts from November to April when temperatures can rise up to 40 °C (104 °F) around April. Disastrous flooding occurred in 2001 and again in 2002, with some degree of flooding almost every year.

Wildlife

Cambodia has a wide variety of plants and animals. There are 212 mammal species, 536 bird species, 240 reptile

species, 850 freshwater fish species (Tonle Sap Lake area), and 435

marine fish species. Much of this biodiversity is contained around the