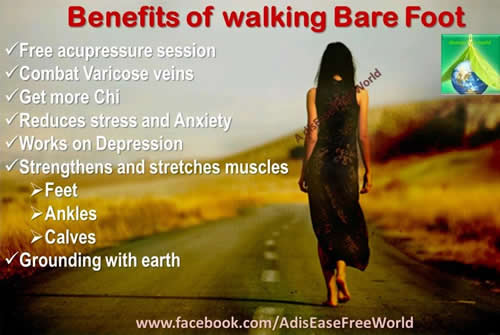

Your

tired feet take the weight of your entire body. What if we told you

that you could pamper them and lose weight in the process.

E2. சமுதயசத்தியத்தை(தோற்ற ஸத்தியத்தை) விளக்கிக்காட்டுதல்

மற்றும் எது, பிக்குளே,

E2. சமுதயசத்தியத்தை(தோற்ற ஸத்தியத்தை) விளக்கிக்காட்டுதல்

மற்றும் எது, பிக்குளே,

dukkha-samudaya ariyasacca துக்கத்தின் மூலக்காரணமான மேதக்க மெய்ம்மை ?

அது இந்த, மறுபிறப்பிற்கு வழிகாட்டும் அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, அத்துடன் இணைக்கப்பட்ட ஆர்வ வேட்கை மற்றும் இன்பம்

நுகர்தல், இங்கும் அங்குமாக களிப்பூட்டு காண்டல், அதை வாக்காட: kāma-taṇhā,

bhava-taṇhā and vibhava-taṇhā புலனுணர்வுக்கு ஆட்பட்ட சபல இச்சை, மறுமுறை

தொடர்ந்து உயிர் வாழ அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை மற்றும் மறுமுறை தொடர்ந்து உயிர்

வாழாதிருக்க அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை. ஆனால் இந்த taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத

ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, பிக்குளே, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில்,

அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

நிலைகொள்கிறது? அங்கே இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும்

ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிற , அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத

ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

மற்றும் எது இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே

எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறது? இந்த கண்கள்

உலகத்தினுள்ளே மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறது,

அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை ,

எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற

நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது,இந்த காது உலகத்தினுள்ளே

மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறது, அங்கே தான்

taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும்

நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது

எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது. இந்த மூக்கு உலகத்தினுள்ளே மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும்

ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறது, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத

ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

இந்த நாக்கு உலகத்தினுள்ளே மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறது, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது. இந்த Kāya காயம் உடல்

உலகத்தினுள்ளே மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறது,

அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை,

எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற

நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது. இந்த Mana மனம் உலகத்தினுள்ளே

மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறது, அங்கே தான்

taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும்

நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது

எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

கண்ணுக்கு

தெரிகிற படிவங்கள் இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும்

ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத

ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

ஒலிகள், இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது. வாசனைகள், இந்த

உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது. சுவைகள் இந்த

உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.உடலியல்பான

புலனுணர்வாதம் இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும்

ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத

ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

Dhammas

தம்மங்கள் யாவுங் கடந்த மெய்யாகக் காண்டல் கட்டம் இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை

மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான்

taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும்

நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது

எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

இந்த eye-viññāṇa கண்-விழிப்புணர்வுநிலை இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை

மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான்

taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும்

நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது

எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.இந்த ear-viññāṇa காது-விழிப்புணர்வுநிலை இந்த

உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.இந்த nose-viññāṇa

மூக்கு-விழிப்புணர்வுநிலை இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும்

ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத

ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

இந்த tongue-viññāṇa நாக்கு-விழிப்புணர்வுநிலை இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை

மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான்

taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும்

நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது

எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது. இந்த Kāyaகாயம் -viññāṇa உடம்பு-விழிப்புணர்வுநிலை

இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

இந்த Mana-viññāṇa

மனம்-விழிப்புணர்வுநிலை இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும்

ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத

ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

இந்த eye-samphassa கண்-தொடர்பு இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற

மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க

முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில்,

அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

நிலைகொள்கிறது.இந்த ear-samphassa காது-தொடர்பு இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை

மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான்

taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும்

நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது

எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.இந்த nose-samphassa மூக்கு-தொடர்பு இந்த

உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது. இந்த tongue-samphassa

நாக்கு-தொடர்பு இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும்

ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத

ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

இந்த Kāyaகாயம் -samphassa உடம்பு-தொடர்பு இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை

மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான்

taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும்

நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது

எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது. இந்த Mana-samphassa மனம்-தொடர்பு இந்த

உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

The vedanāவேதனையால் பிறந்த இந்த eye-samphassa கண்-தொடர்பு இந்த

உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.இந்த ear-samphassa

காது-தொடர்பு இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும்

ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத

ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.இந்த

nose-samphassa மூக்கு-தொடர்பு இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற

மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க

முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில்,

அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

நிலைகொள்கிறது. இந்த tongue-samphassa நாக்கு-தொடர்பு இந்த

உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

இந்த Kāyaகாயம்

-samphassa உடம்பு-தொடர்பு இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும்

ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத

ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

நிலைகொள்கிறது.

இந்த Mana-samphassa மனம்-தொடர்பு இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை

மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான்

taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும்

நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது

எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

இந்த saññā புலனுணர்வு கண்ணுக்கு தெரிகிற படிவங்கள் இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை

மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான்

taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும்

நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது

எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது. saññā புலனுணர்வு ஒலிகள், இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை

மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான்

taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும்

நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது

எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது. saññā புலனுணர்வு வாசனைகள், இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை

மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான்

taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும்

நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது

எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது. saññā புலனுணர்வு சுவைகள் இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை

மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான்

taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும்

நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது

எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

saññā புலனுணர்வு உடலியல்பான புலனுணர்வாதம் இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை

மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான்

taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும்

நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது

எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

saññā புலனுணர்வு Dhammas தம்மங்கள் யாவுங் கடந்த மெய்யாகக் காண்டல் கட்டம்

இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

இந்த புலனுணர்வு தொகுத்த பொதுக் கருத்துப்படிவம் தொடர்புடைய கண்ணுக்கு

தெரிகிற படிவங்கள் இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும்

ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத

ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

ஒலிகள், இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது. வாசனைகள், இந்த

உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது. சுவைகள் இந்த

உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது. உடலியல்பான

புலனுணர்வாதம் இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும்

ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத

ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது. Dhammas

தம்மங்கள் யாவுங் கடந்த மெய்யாகக் காண்டல் கட்டம் இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை

மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான்

taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும்

நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது

எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

இந்த taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை,

கண்ணுக்கு தெரிகிற படிவங்கள் இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும்

ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத

ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

ஒலிகள், இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது. வாசனைகள், இந்த

உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது. சுவைகள் இந்த

உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

உடலியல்பான

புலனுணர்வாதம் இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும்

ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத

ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

நிலைகொள்கிறது.

Dhammas தம்மங்கள் யாவுங் கடந்த மெய்யாகக் காண்டல் கட்டம்

இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

இந்த vitakka எண்ணம்/எதிரொளி கண்ணுக்கு தெரிகிற படிவங்கள் இந்த

உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது. ஒலிகள், இந்த

உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது. வாசனைகள், இந்த

உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது. சுவைகள் இந்த

உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

உடலியல்பான

புலனுணர்வாதம் இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும்

ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத

ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

நிலைகொள்கிறது.

Dhammas தம்மங்கள் யாவுங் கடந்த மெய்யாகக் காண்டல் கட்டம்

இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

இந்த vicāra ஒரு விஷயம் முடியும் முன்பே மற்றொரு விஷயத்திற்கு மாறுகி

எண்ணம் கண்ணுக்கு தெரிகிற படிவங்கள் இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற

மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க

முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில்,

அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

நிலைகொள்கிறது. ஒலிகள், இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும்

ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத

ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

வாசனைகள், இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும்

ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத

ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

சுவைகள் இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

உடலியல்பான

புலனுணர்வாதம் இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும்

ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக் காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத

ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச் சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

யெழும்புகிறது, தானே நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே

நிலைகொள்கிறது.

Dhammas தம்மங்கள் யாவுங் கடந்த மெய்யாகக் காண்டல் கட்டம்

இந்த உலகத்தினுள்ளே எவை மகிழ்வளிக்கிற மற்றும் ஒத்துக்கொள்கிறதாகக்

காணப்படுகிறதோ, அங்கே தான் taṇhā அடக்க முடியாத ஆசை/இச்சை/தாகம்/தகாச்

சிற்றின்பவேட்கை, எழும்பும் நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே யெழும்புகிறது, தானே

நிலைகொள்கிற நேரத்தில், அது எங்கே நிலைகொள்கிறது.

E2. சமுதாயஸச்ச நித்தேசஸ

Katamaṃ ca, bhikkhave, dukkha·samudayaṃ ariya·saccaṃ? Y·āyaṃ taṇhā ponobbhavikā nandi·rāga·sahagatā tatra·tatr·ābhinandinī, seyyathidaṃ: kāma-taṇhā, bhava-taṇhā, vibhava-taṇhā. Sā kho pan·esā, bhikkhave, taṇhā kattha uppajjamānā uppajjati, kattha nivisamānā nivisati? Yaṃ loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati.

.

Kiñca loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ? Cakkhu loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Sotaṃ loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Ghānaṃ loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Jivhā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Kayo loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Mano loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati.

Rūpā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Saddā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Gandhā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Rasā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Phoṭṭhabbā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Dhammā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati

Cakkhu·viññāṇaṃ loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Sota·viññāṇaṃ loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Ghāna·viññāṇaṃ loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Jivhā·viññāṇaṃ loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Kāya·viññāṇaṃ loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Mano·viññāṇaṃ loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati.

Cakkhu·samphasso loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Sota·samphasso loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Ghāna·samphasso loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Jivhā·samphasso loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Kāya·samphasso loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Mano·samphasso loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati.

Cakkhu·samphassa·jā vedanā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Sota·samphassa·jā vedanā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Ghāna·samphassa·jā vedanā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Jivhā·samphassa·jā vedanā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Kāya·samphassa·jā vedanā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Mano·samphassa·jā vedanā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati.

Rūpā·saññā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Sadda·saññā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Gandha·saññā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Rasa·saññā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Phoṭṭhabba·saññā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Dhamma·saññā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati.

Rūpā·sañcetanā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Sadda·sañcetanā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Gandha·sañcetanā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Rasa·sañcetanā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Phoṭṭhabba·sañcetanā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Dhamma·sañcetanā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati.

Rūpā·taṇhā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Sadda·taṇhā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Gandha·taṇhā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Rasa·taṇhā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Phoṭṭhabba·taṇhā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Dhamma·taṇhā loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati.

Rūpā·vitakko loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Sadda·vitakko loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Gandha·vitakko loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Rasa·vitakko loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Phoṭṭhabba·vitakko loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Dhamma·vitakko loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati.

Rūpā·vicāro loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Sadda·vicāro loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Gandha·vicāro loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Rasa·vicāro loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Phoṭṭhabba·vicāro loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Dhamma·vicāro loke piya·rūpaṃ sāta·rūpaṃ etthesā taṇhā uppajjamānā uppajjati, ettha nivisamānā nivisati. Idaṃ vuccati, bhikkhave, dukkha·samudayaṃ ariyasaccaṃ.

E2. Exposition of Samudayasacca

And what, bhikkhus, is the dukkha-samudaya ariyasacca( Cessation of suffering, nibbāṇa(Ultimate Goal of Eternal Bliss)Sublime truth, Noble truth)? It is this taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence) leading to rebirth, connected with desire and enjoyment, finding delight here or there, that is to say: kāma-taṇhā(Fond or desirous of sensual pleasure), bhava-taṇhā( Lord, Sir) and vibhava-taṇhā(Power, prosperity, majesty, splendour; property, wealth). But this taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence),

bhikkhus, when arising, where does it arise, and when settling

[itself], where does it settle? In that in the world which seems

pleasant and agreeable, that is where taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, where when settling, it settles.

And what in the world is pleasant and agreeable? The eye in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The ear in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The nose in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The tongue in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. Kāya(Referring to the body) in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. Mana(and (manaṃ)The mind, the intellect, the thoughts, the heart) in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles.

Visible forms in the world are pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. Sounds in the world are pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. Smells in the world are pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. Tastes in the world are pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. Bodily phenomena in the world are pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. Dhammas(Name of the first book of the Abhidhamma piṭaka and (dhammaṃ)Nature/ condition/ quality/ property/

characteristic; function/ practice/ duty; object/ thing/ idea/

phenomenon; doctrine; law; virtue/ piety; justice; the law or Truth of

the Buddha; the Buddhist scriptures; religion) in the world are pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles.

The eye-viññāṇa(Intelligence, knowledge; consciousness; thought, mind) in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The ear-viññāṇa in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The nose-viññāṇa(Intelligence, knowledge; consciousness; thought, mind) in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The tongue-viññāṇa(Intelligence, knowledge; consciousness; thought, mind) in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. Kāya-viññāṇa in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. Mana-viññāṇa(Intelligence, knowledge; consciousness; thought, mind) in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles.

The eye-samphassa(Contact) in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The ear-samphassa(Contact) in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The nose-samphassa(Contact) in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The tongue-samphassa(Contact) in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. Kāya-samphassa(Contact) in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. Mana-samphassa in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles.

The vedanā born of eye-samphassa(Contact) in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The vedanā born of ear-samphassa(Contact) in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The vedanā born of nose-samphassa(Contact) in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The vedanā born of tongue-samphassa(Contact) in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The vedanā born of kāya-samphassa(Contact) in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The vedanā born of mana-samphassa(Contact) in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles.

The saññā( Sense, consciousness, perception; intellect, thought; sign, gesture; name) of visible forms in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The saññā of sounds in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The saññā( Sense, consciousness, perception; intellect, thought; sign, gesture; name) of smells in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The saññā( Sense, consciousness, perception; intellect, thought; sign, gesture; name) of tastes in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The saññā( Sense, consciousness, perception; intellect, thought; sign, gesture; name) of bodily phenomena in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The saññā( Sense, consciousness, perception; intellect, thought; sign, gesture; name) of Dhammas(Name of the first book of the Abhidhamma piṭaka and (dhammaṃ)Nature/ condition/ quality/ property/

characteristic; function/ practice/ duty; object/ thing/ idea/

phenomenon; doctrine; law; virtue/ piety; justice; the law or Truth of

the Buddha; the Buddhist scriptures; religion) in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles.

The intention [related to] visible forms in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence),

when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The intention

[related to] sounds in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence),

when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The intention

[related to] smells in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence),

when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The intention

[related to] tastes in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence),

when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The intention

[related to] bodily phenomena in the world is pleasant and agreeable,

there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The intention [related to] dhammas in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles.

The taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence) for visible forms in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence) for sounds in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence) for smells in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence) for tastes in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence) for bodily phenomena in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence) for dhammas(Name of the first book of the Abhidhamma piṭaka and (dhammaṃ)Nature/ condition/ quality/ property/

characteristic; function/ practice/ duty; object/ thing/ idea/

phenomenon; doctrine; law; virtue/ piety; justice; the law or Truth of

the Buddha; the Buddhist scriptures; religion) in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles.

The vitakka(Reasoning) of visible forms in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The vitakka(Reasoning) of sounds in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The vitakka(Reasoning) of smells in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The vitakka(Reasoning) of tastes in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The vitakka(Reasoning) of bodily phenomena in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles. The vitakka(Reasoning) of dhammas(Name of the first book of the Abhidhamma piṭaka and (dhammaṃ)Nature/ condition/ quality/ property/

characteristic; function/ practice/ duty; object/ thing/ idea/

phenomenon; doctrine; law; virtue/ piety; justice; the law or Truth of

the Buddha; the Buddhist scriptures; religion) in the world is pleasant and agreeable, there taṇhā(Lust, desire, human passion. Taṇhā is a technical

termthat is found in Buddhist philosophy, and is one of the links of the

paṭiccasamuppāda. The three taṇhās are kāmataṇhā, rūpat., arūpat.,

desire for rebirth in the three forms of existence), when arising, arises, there when settling, it settles.

Please Watch:

http://io9.com/buddhism/

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EwuQRUuZ76w&feature=player_embedded -10:09 Mins

for

Monkey meets Buddha

One of the classic kids’ anime shows that made its way across the Pacific was Monkey Magic,

and it was full of fighting, jokes . . . and very deep lessons about

philosophy and ethics. I love this one in particular, where Monkey meets

Buddha, and learns that he is but a puny dot in the universe occupied

by Buddha, and that selfishness causes pain to others. Complete with

trippy animations as Monkey dives deep into Buddha’s mind and makes

terrifying discoveries about the nature of being. The best part is that

the whole thing is based on an actual Buddhist story.

Here’s the bouncy opening credit sequence to this seriously weird (and tragically forgotten) show.

Suttantapiñake

Dãghanikàyo

Sãlakkhandhavaggo

Namo tassa bhagavato arahato sammàsambuddhassa.

11. Kevaóóha suttaü

1. Evaü

me sutaü: ekaü samayaü bhagavà nàëandàya viharati pàvàrikambavane. Atha

kho kevaóóho gahapatiputto yena bhagavà tenupasaïkami. Upasaïkamitvà

bhagavantaü abhivàdetvà ekamantaü nisãdi. Ekamantaü nisinno kho kevaóóho

gahapatiputto bhagavantaü etadavoca: ‘ayaü bhante nàëandà iddhà ceva

thità ca, bahujanà àkiõõamanussà, bhagavati abhippasannà. Sàdhu bhante

bhagavà ekaü bhikkhuü samàdisatu yo uttarimanussadhammà

iddhipàñibhàriyaü karissati. Evàyaü nàëandà bhiyyosomattàya bhagavati

abhippasãdissatã’ti.

2. Evaü vutte

bhagavà kevaóóhaü gahapatiputtaü etadavoca: na kho ahaü kevaóóha

bhikkhånaü evaü dhammaü desemi ‘etha tumhe bhikkhave gihãnaü

odàtavasanànaü uttarimanussadhammà iddhipàñihàriyaü karothà’ti.

3. Dutiyampi

kho kevaóóho gahapatiputto bhagavantaü etadavoca: nàhaü bhante

bhagavantaü dhaüsemi. Api ca evaü vadàmi: “ayaü bhante nàëanda iddhà

ceva phãtà ca, bahujanà àkiõõamanussà, bhagavati abhippasannà. Sàdhu

bhante bhagavà ekaü bhikkhuü samàdisatu yo uttarimanussadhammà [PTS Page

212] [\q 212/] iddhipàñihàriyaü karissati. Evàyaü nàëandà

bhiyyosomattàya bhagavati abhippasãdissatã’ti. Dutiyampi kho bhagavà

kevaóóhaü gahapatiputtaü etadavoca: na kho ahaü kevaóóha bhikkhånaü evaü

dhammaü desemi ‘etha tumhe bhikkhave gihãnaü odàtavasanànaü

uttarimanussadhammà iddhipàñihàriyaü karothà’ti.

4. Tatiyampi

kho kevaóóho gahapatiputto bhagavantaü etadavoca: nàhaü bhante

bhagavantaü dhaüsemi. Api ca evaü vadàmi: ‘ayaü bhante nàëandà iddhà

ceva phãtà ca, bahujanà àkiõõamanussà, bhagavati abhippasannà. Sàdhu

bhante bhagavà ekaü bhikkhuü samàdisatu yo uttarimanussadhammà

iddhipàñihàriyaü karissati. Evàyaü nàëandà bhiyyosomattàya bhagavati

abhippasãdissatã’ti.

1. Kevañño sãmu.

[BJT Page 486] [\x 486/]

5. “Tãõi kho

imàni kevaóóha pàñihàriyàni mayà sayaü abhi¤¤à sacchikatvà paveditàni.

Katamàni tãõi? Iddhipàñihàriyaü àdesanàpàñihàriyaü.

Anusàsanãpàñihàriyanti. Katama¤ca kevaóóha iddhipàñihàriyaü? Idha

kevaóóha bhikkhu anekavihitaü iddhavidhaü paccanubhoti: eko’pi hutvà

bahudhà hoti. Bahudhà pi hutvà eko hoti. âvãbhàvaü tirobhàvaü,

tirokuóóaü tiropàkàraü tiropabbataü asajjamàno gacchati seyyathàpi

àkàse. Pañhaviyàpi ummujjanimujjaü karoti seyyathàpi udake. Udake’pi

abhijjamàne gacchati seyyathàpi pañhaviyaü. âkàse’pi pallaïkena kamati

seyyathàpi pakkhã sakuõo. Ime’pi candimasuriye evaümahiddhike

evaümahànubhàve pàõinà parimasati parimajjati. Yàva brahmalokàpi kàyena

vasaü vatteti.

6. Tamenaü

a¤¤ataro saddho pasanno passati taü bhikkhuü anekavihitaü iddhividhaü

paccanubhonteü: ekampi hutvà bahudhà bhontaü, bahudhàpi hutvà ekaü

bhontaü, àcãbhàvaü tirobhàvaü tirokuóóhaü tiropàkàraü tiropabbataü

asajjamànaü gacchantaü seyyathàpi àkàse, pañhaviyàpi ummujjanimujjaü

kàrontaü seyyathàpi [PTS Page 213] [\q 213/] udake, udake’pi abhijjamàne

gacchantaü seyyathàpi pañhaviyaü, àkàse’pi pallaïkena kamantaü

seyyathàpi pakkhã sakuõo, ime’pi candimasuriye evaümahiddhike

evaümahànubhàve pàõinà parimasantaü parimajjantaü, yàva brahmalokàpi

kàyena vasaü vattentaü.

7. Tamenaü so

saddho pasanno a¤¤atarassa assaddhassa appasannassa àroceti: acchariyaü

vata bho abbhutaü vata bho samaõassa mahiddhikatà mahànubhàvatà. Amàhaü

bhikkhuü addasaü anekavihitaü iddhimidhaü paccanubhontaü: ekampi hutvà

bahudhà bhontaü, bahudhàpi hutvà ekampi bhontaü, àcãbhàvaü tirobhàvaü

tirokuóóhaü tiropàkàraü tiropabbataü asajjamànaü gacchantaü seyyathàpi

àkàse, pañhaviyàpi ummujjanimujjaü kàrontaü seyyathàpi udake, udake’pi

abhijjamàne gacchantaü seyyathàpi pañhaviyaü, àkàse’pi pallaïkena

kamantaü seyyathàpi pakkhã sakuõo, ime’pi candimasuriye evaümahiddhike

evaümahànubhàve pàõinà parimasantaü parimajjantaü, yàva brahmalokàpi

kàyena vasaü vattentanti. Tamesaü so assaddho appasanno taü saddhaü

pasannaü evaü vadeyya: atthi kho bho gandhàrã nàma vijjà. Tàya so

bhikkhu anekavihitaü iddhividhaü paccanubhoti: eko’pi hutvà bahudhà

hoti. Bahudhà pi hutvà eko hoti. âvãbhàvaü tirobhàvaü, tirokuóóaü

tiropàkàraü tiropabbataü asajjamàno gacchati seyyathàpi àkàse.

Pañhaviyàpi ummujjanimujjaü karoti seyyathàpi udake. Udake’pi

abhijjamàne gacchati seyyathàpi pañhaviyaü. âkàse’pi pallaïkena kamati

seyyathàpi pakkhã sakuõo. Ime’pi candimasuriye evaümahiddhike

evaümahànubhàve pàõinà parimasati parimajjati. Yàva brahmalokàpi kàyena

vasaü vattetãti. Taü kiü ma¤¤asi kevaóóha? Api nu so assaddho appasanno

taü saddhaü pasannaü evaü vadeyya?”Ti. “Vadeyya bhante”ti. “Imaü kho

ahaü kevaóóha iddhipàñihàriye àdãnavaü sampassamàno iddhipàñihàriyena

aññiyàmi haràyàmi jigucchàmi.

1. Eko’pi. (Sãmu. [PTS] ]

[BJT Page 488] [\x 488/]

8. Katama¤ca

kevaóóha àdesanàpàñihàriyaü? Idha kevaóóha bhikkhu parasattànaü

parapuggalànaü cittampi àdisati cetasikampi àdisati vitakkitampi àdisati

vicàritampi àdisati: evampi te mano, itthampi te mano, itipi te

cittanti. Tamenaü a¤¤ataro saddho pasanno passati taü bhikkhuü

parasantànaü parapuggalànaü cittampi àdisantaü cetasikampi àdisantaü

vitakkitampi àdisantaü vicàritampi àdisantaü: evampi te mano, itthampi

te mano, iti’pi te cittanti. Tamenaü so saddho pasanno a¤¤atarassa

assaddhassa appasannassa àroceti: acchariyaü vata bho [PTS Page 214] [\q

214/] abbhutaü vata bho samaõassa mahiddhikatà mahànubhàvatà. Amàhaü

bhikkhuü addasaü parasattànaü parapuggalànaü cittampi àdisantaü

ceteyitampi àdisantaü vitakkitampi àdisantaü vicàritampi àdisantaü:

evampi te mano, itthampi te mano, iti’pi te cittanti. Tamenaü so

assaddho appasanno taü saddhaü pasannaü evaü vadeyya: atthi kho bho

maõikà nàma vijjà. Tàya so bhikkhu parasattànaü parapuggalànaü cittampi

àdisati, cetasikampi àdisati, vitakkitampi àdisati, vicàritampi àdisati:

evampi te mano, itthampi te mano, itipi te cittanti. Taü kiü ma¤¤asi

kevaóóha? Api nu so assaddho appasanto taü saddhaü pasannaü evaü

vadeyyà?”Ti. “Vadeyya bhante”ti. Imaü kho ahaü kevaóóa àdesanà

pàñihàriye àdãnavaü sampassamàno àdesanàpàñihàriyena aññiyàmi haràyàmi

jigucchàmi.

9. Katama¤ca

kevaóóha anusàsanãpàñihàriyaü? Idha kevaóóha bhikkhu evamanusàsati: evaü

vitakketha, mà evaü vitakkayittha, evaü manasikarotha, mà evaü

manasàkattha, idaü pajahatha, idaü upasampajja viharathàti. Idampi

vuccati kevaóóha anusàsanãpàñihàriyaü.

10. Puna ca

paraü kevaóóha idha tathàgato loko uppajjati arahaü sammàsambuddho

vijjàcaraõasampanno sugato lokavidå anuttaro purisadammasàrathã satthà

devamanussànaü buddho bhagavà. So imaü lokaü sadevakaü samàrakaü

sabrahmakaü sassamaõabràhmaõiü pajaü sadevamanussaü sayaü abhi¤¤à

sacchikatvà pavedeti. So dhammaü deseti àdikalyàõaü majjhekalyàõaü

pariyosànakalyàõaü sàtthaü sabya¤janaü kevalaparipuõõaü parisuddhaü.

Brahmacariyaü pakàseti.

[BJT Page 490] [\x 490/]

11(29). Taü

dhammaü suõàti gahapati và gahapatiputto và a¤¤atarasmiü và kule

paccàjàto. So taü dhammaü sutvà tathàgate saddhaü pañilabhati. So tena

saddhàpañilàbhena samannàgato iti pañisaücikkhati: ’sambàdho gharàvaso

rajàpatho1. Abbhokàso pabbajjà. Nayidaü sukaraü agàraü ajjhàvasatà

ekantaparipuõõaü ekantaparisuddhaü saükhalikhitaü brahmacariyaü carituü.

Yannånàhaü kesamassuü ohàretvà kàsàyàni vatthàni acchàdetvà agàrasmà

anagàriyaü pabbajeyya’nti.

1. Rajopatho, katthaci.

So aparena

samayena appaü và bhogakkhandhaü pahàya mahantaü và bhogakkhandhaü

pahàya appaü và ¤àtiparivaññaü pahàya mahantaü và ¤àtiparivaññaü pahàya

kesamassuü ohàretvà kàsàyàni vatthàni acchàdetvà agàrasmà anagàriyaü

pabbajati. So evaü pabbajito samàno pàtimokkhasaüvarasaüvuto viharati

àcàragocarasampanno aõumattesu vajjesu bhayadassàvã. Samàdàya sikkhati

sikkhàpadesu kàyakammavacãkammena samannàgato kusalena. Parisuddhàjãvo

sãlasampanno indriyesu guttadvàro bhojane matta¤¤å satisampaja¤¤esu

samannàgato santuññho.

12 (29)

Katha¤ca kevaóóha bhikkhu sãlasampanno hoti? Idha kevaóóha bhikkhu

pàõàtipàtaü pahàya pàõàtipàtà pañivirato hoti nihitadaõóo nihitasattho

lajjã dayàpanno. Sabbapàõabhåtahitànukampã viharati. Idampi’ssa hoti

sãlasmiü.

Adinnàdànaü

pahàya adinnàdànà pañivirato hoti dinnàdàyã dinnapàñikaïkhã. Athenena

sucibhåtena attanà viharati. Idampi’ssa hoti sãlasmiü.

Abrahmacariyaü pahàya brahmacàrã hoti àràcàrã1 virato methunà gàmadhammà. Idampi’ssa hoti sãlasmiü.

Musàvàdaü pahàya musàvàdà pañivirato hoti saccavàdã saccasandho theto2 paccayiko avisaüvàdako lokassa. Idampi’ssa hoti sãlasmiü.

Pisuõaü vàcaü3

pahàya pisuõàya vàcàya pañivirato hoti. Ito sutvà na amutra akkhàtà

imesaü bhedàya. Amutra và sutvà na imesaü akkhàtà amåsaü bhedàya. Iti

bhinnànaü và sandhàtà, sahitànaü và anuppadàtà4 samaggàràmo5 samaggarato

samagganandiü samaggakaraõiü vàcaü bhàsità hoti. Idampi’ssa hoti

sãlasmiü.

[BJT Page 492] [\x 492/]

Pharusaü

vàcaü6 pahàya pharusàya vàcàya pañivirato hoti. Yà sà vàcà neëà

kaõõasukhà pemanãyà7 hadayaïgamà porã bahujanakantà bahujanamanàpà,

tathàråpaü8 vàcaü bhàsità hoti. Idampi’ssa hoti sãlasmiü.

Samphappalàpaü

pahàya samphappalàpà pañivirato hoti kàlavàdã bhåtavàdã atthavàdã

dhammavàdã vinayavàdã. Nidhànavatiü vàcaü bhàsità hoti kàlena sàpadesaü

pariyantavatiü atthasa¤hitaü. Idampi’ssa hoti sãlasmiü.

1. Anàcàri, machasaü.

2. òheto, syà.

3. Pisuõàvàcaü, [PTS]

4. Anuppàdàtà, [PTS]

5. Samaggaràmo, machasaü.

6. Pharusàvàcaü, [PTS] Sitira

7. Pemaniyà, machasaü. 8. Evaråpiü. [PTS] Sitira.

13(30)

Bãjagàmabhåtagàmasamàrambhà1 pañivirato hoti. Ekabhattiko2 hoti

rattåparato3 pañivirato4 vikàlabhojanà. Naccagãtavàditavisåkadassanà5

pañivirato hoti. Màlàgandhavilepanadhàraõamaõóanavibhusanaññhànà

pañivirato hoti. Uccàsayanamahàsayanà pañivirato hoti.

Jàtaråparajatapañiggahaõà6 pañivirato hoti. âmakadha¤¤apañiggahaõà6

pañivirato hoti. âmakamaüsapañiggahaõà6 pañivirato hoti.

Itthikumàrikapañiggahaõà6 pañivirato hoti. Dàsidàsapañiggahaõà6

pañivirato hoti. Ajeëakapañiggahaõà6 pañivirato hoti.

Kukkuñasåkarapañiggahaõà6 pañivirato hoti. Hatthigavassavaëavà7

pañiggahaõà pañivirato hoti. Khettavatthupañiggahaõà pañivirato hoti.

Dåteyyapaheõa8 gamanànuyogà pañivirato hoti. Kayavikkayà pañivirato

hoti. Tulàkåñakaüsakåñamànakåñà9 pañivirato hoti.

Ukkoñanava¤cananikatisàci10 yogà pañivirato hoti.

Chedanavadhabandhanaviparàmosaàlopasahasàkàrà11 pañivirato hoti.

Idampi’ssa hoti sãlasmiü.

Cullasãlaü12 niññhitaü

14 (31) Yathà

và paneke bhonto samaõabràhmaõà saddhàdeyyàni bhojanàni bhu¤jitvà te

evaråpaü bãjagàmabhåtagàmasamàrambhaü13 anuyuttà viharanti, seyyathãdaü:

målabãjaü khandhabãjaü phalubãjaü14 aggabãjaü bijabãjameva15 pa¤camaü.

Iti và itievaråpà16 bãjagàmabhåtagàmasamàrambhà17 pañivirato hoti.

Idampi’ssa hoti sãlasmiü.

1. Pemaniyà,mamachasaü. 2. Evaråpã, [PTS]

[BJT Page 494] [\x 494/]

15(32) Yathà

và paneke bhonto samaõabràhmaõà saddhàdeyyàni bhojanàni bhu¤jitvà te

evaråpaü sannidhikàraparibhogaü anuyuttà viharanti, seyyathãdaü:

annasannidhiü pànasannidhiü vatthasannidhiü yànasannidhiü

sayanasannidhiü gandhasannidhiü àmisasannidhiü. Iti và iti evaråpà

sannidhikàraparibhogà pañivirato hoti. Idampi’ssa hoti sãlasmiü.

1. Samàrabbhà, machasaü.

2. Ekaü bhattiko, machasaü.

3. Rattuparato, machasaü.

4. Virato, the. Se.

5. Visåkaü, machasaü.

6. Pariggahaõà, (sabbattha)

7. Gavassaü, se. Vaëavaü, machasaü.

8. Pahiõa, sãmu. Machasa. Syà.

9. Kåñaü, machasaü.

10. Sàvi, machasaü.

11. Sahasaü, machasaü.

12. Cåëa sãlaü, machasaü.

13. Samàrabbhà, machasaü.

14. Phalaü, se. Phaluü, si. The.

15. Bija bãjaü eva. The.

16. Iti evarupà, kesuci.

17. Samàrabbhà, machasaü.

16(33). Yathà

và paneke bhonto samaõabràhmaõà saddhàdeyyàni bhojanàni bhu¤jitvà te

evaråpaü visåkadassanaü anuyuttà viharanti, seyyathãdaü: naccaü gãtaü

vàditaü pekkhaü akkhàtaü pàõissaraü vetàlaü kumbhathånaü sobhanakaü1

caõóàlaü vaüsaü dhopanakaü2 hatthiyuddhaü assayuddhaü mahisayuddhaü3

usabhayuddhaü ajayuddhaü meõóayuddhaü4 kukkuñayuddhaü vaññakayuddhaü

daõóayuddhaü muññhiyuddhaü5 nibbuddhaü uyyodhikaü balaggaü senàbyåhaü

aõãkadassanaü6. Iti và iti evaråpà visåkadassanà pañivirato hoti.

Idampi’ssa hoti sãlasmiü.

17(34). Yathà

và paneke bhonto samaõabràhmaõà saddhàdeyyàni bhojanàni bhu¤jitvà te

evaråpaü jåtappamàdaññhànànuyogaü anuyuttà viharanti, seyyathãdaü:

aññhapadaü dasapadaü àkàsaü parihàrapathaü santikaü khalikaü ghañikaü

salàkahatthaü akkhaü païgacãraü vaïkakaü mokkhacikaü ciïgulakaü

pattàëhakaü rathakaü dhanukaü akkharikaü manesikaü yathàvajjaü. Iti và

iti evaråpà jåtappamàdaññhànànuyogà pañivirato hoti. Idampi’ssa hoti

sãlasmiü.

18(35). Yathà

và paneke bhonto samaõabràhmaõà saddhàdeyyàni bhojanàni bhu¤jitvà te

evaråpaü uccàsayanamahàsayanaü anuyuttà viharanti, seyyathãdaü: àsandiü

pallaïkaü gonakaü cittakaü pañikaü pañalikaü tålikaü vikatikaü uddalomiü

ekantalomiü kaññhissaü koseyyaü kuttakaü hatthattharaü assattharaü

rathattharaü ajinappaveõiü kàdalimigapavarapaccattharaõaü

sauttaracchadaü ubhatolohitakåpadhànaü. Iti và iti evaråpà

uccàsayanamahàsayanà pañivirato hoti. Idampi’ssa hoti sãlasmiü.

1. Sobhanagarakaü, katthaci. Sobhanakarakaü, [PTS] Sobhanagharakaü, machasaü.

2. Dhovanaü, katthaci. Dhopanaü, sitira.

3. Mahiüsaü, machasaü.

4. Meõóakaü, machasaü.

5. Sãhala potthakesu na dissati.

6. Anãka - kesuci.

[BJT Page 496] [\x 496/]

19(36). Yathà

và paneke bhonto samaõabràhmaõà saddhàdeyyàni bhojanàni bhu¤jitvà te

evaråpaü maõóanavibhusanaññhànànuyogaü anuyuttà viharanti, seyyathãdaü:

ucchàdanaü parimaddanaü nahàpanaü sambàhanaü àdàsaü a¤janaü

màlàvilepanaü mukhacuõõakaü1 mukhalepanaü2 hatthabandhaü sikhàbandhaü

daõóakaü nàëikaü khaggaü chattaü citråpàhanaü uõhãsaü maõiü vàlavãjaniü

odàtàni vatthàni dãghadasàni. Iti và iti evaråpà

maõóanavibhusanaññhànànuyogà pañivirato hoti. Idampi’ssa hoti sãlasmiü.

20(37). Yathà

và paneke bhonto samaõabràhmaõà saddhàdeyyàni bhojanàni bhu¤jitvà te

evaråpaü tiracchànakathaü anuyuttà viharanti, seyyathãdaü: ràjakathaü

corakathaü mahàmattakathaü senàkathaü bhayakathaü yuddhakathaü

annakathaü pànakathaü vatthakathaü sayanakathaü màlàkathaü gandhakathaü

¤àtikathaü yànakathaü gàmakathaü nigamakathaü nagarakathaü

janapadakathaü itthikathaü purisakathaü (kumàrakathaü kumàrikathaü)3

sårakathaü visikhàkathaü kumbhaññhànakathaü pubbapetakathaü

nànattakathaü lokakkhàyikaü samuddakkhàyikaü itibhavàbhavakathaü. Iti và

itievaråpàya tiracchànakathàya pañivirato hoti. Idampi’ssa hoti

sãlasmiü.

21(38) Yathà

và paneke bhonto samaõabràhmaõà saddhàdeyyàni bhojanàni bhu¤jitvà te

evaråpà viggàhikakathaü anuyuttà viharanti, seyyathãdaü: “na tvaü imaü

dhammavinayaü àjànàsi. Ahaü imaü dhammavinayaü àjànàmi. Kiü tvaü imaü

dhammavinayaü àjànissasi? Micchàpañipanno tvamasi. Ahamasmi

sammàpañipanno. Sahitaü me, asahitaü te. Pure vacanãyaü pacchà avaca.

Pacchà vacanãyaü pure avaca. âciõõaü4 te viparàvattaü. âropito te vàdo.

Niggahãto tvamasi. Cara vàdappamokkhàya. Nibbeñhehi và sace pahosã”ti.

Iti và itievaråpàya viggàhikakathàya pañivirato hoti. Idampi’ssa hoti

sãlasmiü.

22(39). Yathà

và paneke bhonto samaõabràhmaõà saddhàdeyyàni bhojanàni bhu¤jitvà te

evaråpaü dåteyyapahiõagamanànuyogamanuyuttà viharanti, seyyathãdaü:

ra¤¤aü ràjamahàmattànaü khattiyànaü bràhmaõànaü gahapatikànaü kumàrànaü

“idha gaccha. Amutràgaccha. Idaü hara. Amutra idaü àharà”ti. Iti và

itievaråpà dåteyyapahiõagamanànuyogà pañivirato hoti. Idampi’ssa hoti

sãlasmiü.

1. Mukhacuõõaü, machasaü.

2. Mukhàlepanaü, sãmu.

3. Marammapotthakesuyeva dissate

4. Aviciõõaü, kesuci.

[BJT Page 498] [\x 498/]

23(40). Yathà

và paneke bhonto samaõabràhmaõà saddhàdeyyàni bhojanàni bhu¤jitvà te

kuhakà ca honti lapakà ca nemittikà ca nippesikà ca làbhena ca làbhaü

nijigiüsitàro. Iti và itievaråpà kuhanalapanà pañivirato hoti.

Idampi’ssa hoti sãlasmiü.

Majjhimasãlaü niññhitaü.

24(41). Yathà

và paneke bhonto samaõabràhmaõà saddhàdeyyàni bhojanàni bhu¤jitvà te

evaråpàya tiracchànavijjàya micchàjãvena jãvikaü1 kappenti, seyyathãdaü:

aïgaü nimittaü uppàtaü2 supiõaü3 lakkhaõaü måsikacchinnaü aggihomaü

dabbihomaü thusahomaü taõóulahomaü sappihomaü telahomaü mukhahomaü

lohitahomaü aïgavijjà vatthuvijjà khattavijjà4 sivavijjà bhåtavijjà

bhurivijjà ahivijjà visavijjà vicchikavijjà måsikavijjà sakuõavijjà

vàyasavijjà pakkajjhànaü5 saraparittànaü migacakkaü. Iti và itievaråpàya

tiracchànavijjàya micchàjãvà pañivirato hoti. Idampi’ssa hoti sãlasmiü.

25(42)2. Yathà

và paneke bhonto samaõabràhmaõà saddhàdeyyàni bhojanàni bhu¤jitvà te

evaråpàya tiracchànavijjàya micchàjãvena jãvikaü kappenti, seyyathãdaü:

maõilakkhaõaü vatthalakkhaõaü daõóalakkhaõaü6 asilakkhaõaü usulakkhaõaü

dhanulakkhaõaü àvudhalakkhaõaü7 itthilakkhaõaü purisalakkhaõaü

kumàralakkhaõaü kumàrilakkhaõaü dàsalakkhaõaü dàsilakkhaõaü

hatthilakkhaõaü assalakkhaõaü mahisalakkhaõaü8 usabhalakkhaõaü

golakkhaõaü9 ajalakkhaõaü meõóalakkhaõaü10 kukkuñalakkhaõaü

vaññakalakkhaõaü godhàlakkhaõaü kaõõikàlakkhaõaü kacchapalakkhaõaü

migalakkhaõaü. Iti và itievaråpàya tiracchànavijjàya micchàjãvà

pañivirato hoti. Idampi’ssa hoti sãlasmiü.

26(43). Yathà

và paneke bhonto samaõabràhmaõà saddhàdeyyàni bhojanàni bhu¤jitvà te

evaråpàya tiracchànavijjàya micchàjãvena jãvikaü kappenti seyyathãdaü:

ra¤¤aü niyyànaü bhavissati, ra¤¤aü aniyyànaü bhavissati, abbhantarànaü

ra¤¤aü upayànaü bhavissati, bàhirànaü ra¤¤aü apayànaü bhavissati,

bàhirànaü ra¤¤aü upayànaü bhavissati, abbhantarànaü ra¤¤aü apayànaü

bhavissati, abbhantarànaü ra¤¤aü jayo bhavissati, abbhantarànaü ra¤¤aü

paràjayo bhavissati. Iti imassa jayo bhavissati. Imassa paràjayo

bhavissati. Iti và itievaråpàya tiracchànavijjàya micchàjãvà pañivirato

hoti. Idampi’ssa hoti sãlasmiü.

1. Jãvitaü, machasaü.

2. Uppàdaü, sãmu.

3. Supinaü, machasaü. Supiõakaü, si.

4. Khettaü, kesuci.

5. Pakkha, kesuci.

6. Daõóalakkhaõaü satthalakkhaõaü, machasaü.

7. âyudha, kesuci.

8. Mahiüsa, machasaü.

9. Goõa, machasaü.

10. Meõóaka, kesuci.

[BJT Page 500] [\x 500/]

27(44). Yathà

và paneke bhonto samaõabràhmaõà saddhàdeyyàni bhojanàni bhu¤jitvà te

evaråpàya tiracchànavijjàya micchàjãvena jãvikaü kappenti. Seyyathãdaü:

candaggàho bhavissati. Suriyaggàho bhavissati. Nakkhattagàho bhavissati.

Candimasuriyànaü pathagamanaü bhavissati. Candimasuriyànaü

uppathagamanaü bhavissati. Nakkhattànaü pathagamanaü bhavissati.

Nakkhattànaü uppathagamanaü bhavissati. Ukkàpàto bhavissati. Dãsàóàho

bhavissati. Bhåmicàlo bhavissati. Devadundubhi bhavissati.

Candimasuriyanakkhattànaü uggamanaü ogamanaü1 saükilesaü vodànaü

bhavissati. Evaüvipàko candaggàho bhavissati. Evaüvipàko suriyaggàho

bhavissati. Evaüvipàko nakkhattaggàho bhavissati. Evaüvipàkaü

candimasuriyànaü pathagamanaü bhavissati. Evaüvipàkaü candimasuriyànaü

uppathagamanaü bhavissati. Evaüvipàkaü nakkhattànaü pathagamanaü

bhavissati. Evaüvipàkaü nakkhattànaü uppathagamanaü bhavissati.

Evaüvipàko ukkàpàto bhavissati. Evaüvipàko disàóàho bhavissati.

Evaüvipàko bhåmicàlo bhavissati. Evaüvipàko devadundåbhi bhavissati.

Evaüvipàko candimasuriyanakkhattànaü uggamanaü ogamanaü saïkilesaü

vodànaü bhavissati. Iti và itievaråpàya tiracchànavijjàya micchàjãvà

pañivirato hoti. Idampi’ssa hoti sãlasmiü.

28(45). Yathà

và paneke bhonto samaõabràhmaõà saddhàdeyyàni bhojanàni bhu¤jitvà te

evaråpàya tiracchànavijjàya micchàjãvena jãvikaü kappenti. Seyyathãdaü:

subbuññhikà bhavissati. Dubbuññhikà bhavissati. Subhikkhaü bhavissati.

Dubbhikkhaü bhavissati. Khemaü bhavissati. Bhayaü bhavissati. Rogo

bhavissati. ârogyaü bhavissati. Muddà gaõanà saükhànaü kàveyyaü

lokàyataü. Iti và itievaråpàya tiracchànavijjàya micchàjãvena pañivirato

hoti. Idampi’ssa hoti sãlasmiü.

29(46). Yathà

và paneke bhonto samaõabràhmaõà saddhàdeyyàni bhojanàni bhu¤jitvà te

evaråpàya tiracchànavijjàya micchàjãvena jãvikaü kappenti. Seyyathãdaü:

àvàhanaü vivàhanaü saüvadanaü vivadanaü saükiraõaü vikiraõaü

subhagakaraõaü dubbhagakaraõaü viruddhagabbhakaraõaü jivhànitthambhanaü2

hanusaühananaü hatthàbhijappanaü hanujappanaü kaõõajappanaü àdàsapa¤haü

kumàripa¤haü devapa¤haü àdiccupaññhànaü mahatupaññhànaü abbhujjalanaü

sirivhàyanaü. Iti và itievaråpàya tiracchànavijjàya micchàjãvà

pañivirato hoti. Idampi’ssa hoti sãlasmiü.

1. Oggamanaü, kesuci.

2. Jivhànitthaddhanaü. Bahusu.

[BJT Page 502] [\x 502/]

30(47). Yathà

và paneke bhonto samaõabràhmaõà saddhàdeyyàni bhojanàni bhu¤jitvà te

evaråpàya tiracchànavijjàya micchàjãvena jãvikaü kappenti. Seyyathãdaü:

santikammaü paõidhikammaü bhåtakammaü bhurikammaü vassakammaü

vossakammaü vatthukammaü vatthuparikiraõaü àcamanaü nahàpanaü juhanaü

vamanaü virecanaü uddhavirecanaü adhovirecanaü sãsavirecanaü kaõõatelaü

nettatappanaü natthukammaü a¤janaü pacca¤janaü sàlàkiyaü sallakattiyaü

dàrakatikicchà målabhesajjànaü anuppadànaü osadhãnaü pañimokkho. Iti và

itievaråpàya tiracchànavijjàya micchàjãvà pañivirato hoti. Idampi’ssa

hoti sãlasmiü.

31(48). Sa

kho1 so kevaóóha bhikkhu evaü sãlasampanno na kutoci bhayaü

samanupassati yadidaü sãlasaüvarato. Seyyathàpi màõava khattiyo

muddhàvasitto2 nihatapaccàmitto na kutoci bhayaü samanupassati yadidaü

paccatthikato, evameva kho kevaóóha bhikkhu evaü sãlasampanno na kutoci

bhayaü samanupassati yadidaü sãlasaüvarato. So iminà ariyena

sãlakkhandhena samannàgato ajjhattaü anavajjasukhaü pañisaüvedeti. Evaü

kho kevaóóha bhikkhu sãlasampanno hoti.

32(49).

Katha¤ca kevaóóha bhikkhu indriyesu guttadvàro hoti? Idha kevaóóha

bhikkhu cakkhunà råpaü disvà na nimittaggàhã hoti nànubya¤janaggàhã.

Yatvàdhikaraõamenaü cakkhundriyaü asaüvutaü viharantaü abhijjhà

domanassà pàpakà akusalà dhammà anvassaveyyuü3 tassa saüvaràya

pañipajjati. Rakkhati cakkhundriyaü. Cakkhundriye saüvaraü àpajjati.

Sotena saddaü sutvà na nimittaggàhã hoti nànubya¤janaggàhã.

Yatvàdhikaraõamenaü sotindriyaü asaüvutaü viharantaü abhijjhà domanassà

pàpakà akusalà dhammà anvassaveyyuü tassa saüvaràya pañipajjati.

Rakkhati sotindriyaü. Sotindriye saüvaraü àpajjati. Ghàõena gandhaü

ghàyitvà na nimittaggàhã hoti nànubya¤janaggàhã. Yatvàdhikaraõamenaü

ghàõindriyaü asaüvutaü viharantaü abhijjhà domanassà pàpakà akusalà

dhammà anvassaveyyuü tassa saüvaràya pañipajjati. Rakkhati ghàõindriyaü.

Ghàõindriye saüvaraü àpajjati. Jivhàya rasaü sàyitvà na nimittaggàhã

hoti nànubya¤janaggàhã. Yatvàdhikaraõamenaü jivhindriyaü asaüvutaü

viharantaü abhijjhà domanassà pàpakà akusalà dhammà anvassaveyyuü3 tassa

saüvaràya pañipajjati. Rakkhati jivhindriyaü. Jivhindriye saüvaraü

àpajjati. Kàyena phoññhabbaü phusitvà na nimittaggàhã hoti

nànubya¤janaggàhã. Yatvàdhikaraõamenaü kàyindriyaü asaüvutaü viharantaü

abhijjhà domanassà pàpakà akusalà dhammà anvassaveyyuü3 tassa saüvaràya

pañipajjati. Rakkhati kàyindriyaü. Kàyindriye saüvaraü àpajjati. Manasà

dhammaü vi¤¤àya na nimittaggàhã hoti nànubya¤janaggàhã.

Yatvàdhikaraõamenaü manindriyaü asaüvutaü viharantaü abhijjhà domanassà

pàpakà akusalà dhammà anvassaveyyuü3 tassa saüvaràya pañipajjati.

Rakkhati manindriyaü. Manindriye saüvaraü àpajjati. So iminà ariyena

indriyasaüvarena samannàgato ajjhattaü abyàsekasukhaü pañisaüvedeti.

Evaü kho kevaóóha bhikkhu indriyesu guttadvàro hoti.

1. Atha kho, kesuci.

2. Muddhàbhisinto, kesuci.

3. Anvàsaveyyuü, anvàssaveyyu, kesuci.

[BJT Page 504] [\x 504/]

33(50).

Katha¤ca kevaóóha bhikkhu satisampaja¤¤ena samannàgato hoti? Idha

kevaóóha bhikkhu abhikkante pañikkante sampajànakàrã hoti. âlokite

vilokite sampajànakàrã hoti. Sami¤jite1 pasàrite sampajànakàrã hoti.

Saïghàñipattacãvaradhàraõe sampajànakàrã hoti. Asite pãte khàyite sàyite

sampajànakàrã hoti. Uccàrapassàvakamme sampajànakàrã hoti. Gate ñhite

nisinne sutte jàgarite bhàsite tuõhãbhàve sampajànakàrã hoti. Evaü kho

kevaóóha bhikkhu satisampaja¤¤ena samannàgato hoti.

34(51).

Katha¤ca kevaóóha bhikkhu santuññho hoti? Idha kevaóóha bhikkhu

santuññho hoti kàyaparihàriyena cãvarena kucchiparihàriyena2

piõóapàtena. So yena yeneva pakkamati samàdàyeva pakkamati. Seyyathàpi

kevaóóha pakkhi sakuõo yena yeneva óeti sapattabhàro’va óeti, evameva

kho kevaóóha bhikkhu santuññho hoti kàyaparihàriyena cãvarena

kucchiparihàriyena piõóapàtena. So yena yeneva pakkamati samàdàyeva

pakkamati. Evaü kho kevaóóha bhikkhu santuññho hoti.

35(52). So