18 LESSON-Spiritual Community of The True Followers of The Path Shown by The Awakened One

I. The Reasons for Taking Refuge

When it is said that the practice of the Buddha’s teaching starts with taking refuge, this immediately raises an important question. The question is: “What need do we have for a refuge?” A refuge is a person, place, or thing giving protection from harm and danger. So when we begin a practice by going for refuge, this implies that the practice is intended to protect us from harm and danger. Our original question as to the need for a refuge can thus be translated into another question: “What is the harm and danger from which we need to be protected?” If we look at our lives in review we may not see ourselves exposed to any imminent personal danger. Our jobs may be steady, our health good, our families well-provided for, our resources adequate, and all this we may think gives us sufficient reason for considering ourselves secure. In such a case the going for refuge becomes entirely superfluous.

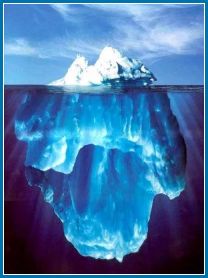

To understand the need for a refuge we must learn to see our position as it really is; that is, to see it accurately and against its total background. From the Buddhist perspective the human situation is similar to an iceberg:

a small fraction of its mass appears above the surface, the vast substratum remains below, hidden out of view. Owing to the limits of our mental vision our insight fails to penetrate beneath the surface crust, to see our situation in its underlying depths. But there is no need to speak of what we cannot see; even what is immediately visible to us we rarely perceive with accuracy. The Buddha teaches that cognition is subservient to wish. In subtle ways concealed from ourselves our desires condition our perceptions, twisting them to fit into the mould they themselves want to impose. Thus our minds work by way of selection and exclusion. We take note of those things agreeable to our pre-conceptions; we blot out or distort those that threaten to throw them into disarray.

From the standpoint of a deeper, more comprehensive understanding the sense of security we ordinarily enjoy comes to view as a false security sustained by unawareness and the mind’s capacity for subterfuge. Our position appears impregnable only because of the limitations and distortions of our outlook. The real way to safety, however, lies through correct insight, not through wishful thinking. To reach beyond fear and danger we must sharpen and widen our vision. We have to pierce through the deceptions that lull us into a comfortable complacency, to take a straight look down into the depths of our existence, without turning away uneasily or running after distractions. When we do so, it becomes increasingly clear that we move across a narrow footpath at the edge of a perilous abyss. In the words of the Buddha we are like a traveler passing through a thick forest bordered by a swamp and precipice; like a man swept away by a stream seeking safety by clutching at reeds; like a sailor crossing a turbulent ocean; or like a man pursued by venomous snakes and murderous enemies. The dangers to which we are exposed may not always be immediately evident to us. Very often they are subtle, camouflaged, difficult to detect. But though we may not see them straightaway the plain fact remains that they are there all the same. If we wish to get free from them we must first make the effort to recognize them for what they are. This, however, calls for courage and determination.

On the basis of the Buddha’s teaching the dangers that make the quest for a refuge necessary can be grouped into three general classes: (1) the dangers pertaining to the present life; (2) those pertaining to future lives; and (3) those pertaining to the general course of existence. Each of these in turn involves two aspects: (A) and objective aspect which is a particular feature of the world; and (B) a subjective aspect which is a corresponding feature of our mental constitution. We will now consider each of these in turn.