Question and Answers

MAHA BODHI SOCIETY-Questionnaire No 8 and Answers of First Year Diploma Course conducted by Mahabodhi

1. Write an essay on the dream of the Bodhisatta on the night prior to Awakenment.

The serene figure of Buddha in meditation-a still surface conceals the inner turmoil raging below. This is the point just prior to enlightenment, a moment of supreme tension when Shakyamuni, about to become a Buddha, must gather all his strength and knowledge to defeat Mara and the powerful forces of illusion. The knowledge and discoveries resulting from this great effort literally changed the world.

2. Write an essay on Sujaataa’s offering of payaasa to the Bodhisatta. Describe fully the procedure.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

Early on the full moon day of Kason (April) in the year 103 of the Great Era, i.e. 2551 years ago, counting back from the year 1324 of the Burmese Era, the now emaciated prince sat down under the Bo Tree (Bodhi Tree) near the big village of Senanigãma awaiting the hour of going for alms food. At that time, Sujãtã, the daughter of a rich man from the village, was making preparations to give an offering to the tree-spirit of the Bo tree. She sent her maid ahead to tidy up the area under the spread of the holy tree. At the sight of the starving man seated under the tree, the maid thought the deity had made himself visible to receive their offering in person. She ran back in great excitement to inform her mistress.

Sujãtã put the milk rice which she had cooked early in the morning in a golden bowl worth a hundred thousand pieces of money. She covered the same with another golden bowl. She then proceeded with the bowls to the foot of the banyan tree where the prince remained seated and put the bowls in the hand of the soon to be Great Bodhisattva, saying, “May your wishes prosper like mine have.” So saying, she departed.

Sujãtã, on becoming a maiden, had made a prayer at the banyan tree: “If I get a husband of equal rank and same caste with myself and my first born is a son, I will make an offering.” Her prayer had been fulfilled and her offering of milk rice that day was intended for the tree deity in fulfillment of her pledge. However, later when she learned that the Bodhisattva had overcome the powers of Mara and gained Awakenment after taking the milk rice offered by her, she was overjoyed with the thought that she had made a noble deed to the greatest merit.

Before the day she was to cook the rice, Sujata had some of her servants lead the herd of 1,000 cows to a forest of licorice grass so that the cows could eat their fill. Then she divided them into two herds of 500 head each, and milked the 500 cows of one herd and fed that milk to the 500 cows of the other herd. She then continued to divide that herd and feed half on the milk of the other half until there were only eight cows left. She then took the milk from those eight cows to make her milk rice.

When the rice was cooked, Sujata sent a servant girl to clean up the area around the banyan tree. The servant girl came back to Sujata with a report that the deity [deva] who was to receive the offerings had materialized, and was already sitting at the foot of the banyan tree. Excited, Sujata lifted the tray of milk rice to her head and carried it to the banyan tree, together with her servant girl. Seeing that it was as her servant had told her, she came forward and proffered the tray of milk rice. The Great Being received it and looked at Sujata. She understood from his look that he had no bowl or any other dish with which to eat the food, and so she made an offering of both the rice and the dish.

Having offered the rice, she walked back to her house, full of happiness, believing that she had made offerings to a deva.

3. What is the significance underlying the fourfold resolution he made before engaging in the battle with Maara.

4. Who is Maara?

5. What was Maara’s demand and why did Siddhattha refuse to yield to Maara’s demand?

MARA

Shakyamuni being tested by the Daughters and Children

of Mara under the Bodhi tree.

the Wanderling

Centuries ago the coming Buddha sat under the Bodhi-tree and vowed not to move until he learned to eradicate suffering, unfolding

Anuttara Samyak Sambodhi, the Consumation of Incomparable Awakenment. But Mara, the personification of evil, tried to usurp his plans by sending his three daughters Tanha (desire), Raga (lust), and Arati (aversion), to seduce him and break his concentration. However, the coming Buddha was too strong for Mara. (source)

In Buddhism Mara is the lord of misfortune, sin, destruction and Death. Mara is the ruler of desire and death, the two evils that chain man to the wheel of ceaseless rebirth. Mara reviles man, blinds him, guides him toward sensuous desires; once man is in his bondage, Mara is free to destroy him.

Buddhist tradition holds that Buddha encountered Mara on several occasions. When he abandoned the traditional ascetic practices of Hinduism, Mara reproached him for straying from the path of purity. Mara later reappeared as a Brahmin, criticising him for neglecting the techniques of the yogins. At another time, Mara persuades householders in a village to refuse to give alms to the Buddha. Mara also accuses Buddha of sleeping too much, and not keeping busy like the villagers.

In a famous incident similar to the temptation of Jesus in the Christian religion, Mara urges Buddha to become a universal king and establish a great empire in which men can live in peace. He reminds Buddha that he can turn the Himalayas into gold if he but wishes so that all men will become rich. Buddha replies that a single man’s wants are so insatiable that even two such golden mountains would fail to satisfy him.”

While Mara is unable to subjugate Buddha, he is more successful with Buddha’s followers, even approaching the Buddha’s own brother, Ananda. As the source of evil, he causes misunderstanding between teachers and pupils, casts doubt on the value of Buddha’s sayings by calling them nothing but poetry, or encourages monks to waste their time on abstruse speculations. Worse, he appears in the guise of a monk, nun, relative or prominent Brahmin, bringing false news that a disciple is destined to be a new Buddha. If the disciple succumbs to the temptation, he will be filled with sinful pride. Mara could even appear in the form of Gautama Buddha in order to confuse Buddhists or lead them astray.

Mara is lord of all men who are bound by sense desires. His origin, according to Theravada commentators, was as a rebellious prince who seized control of our world from the supreme god of the highest heaven. As prince of this world, Mara can boast of possessing great majesty and influence. Though he has only a spirit body, he is endowed with the five modes of sensual pleasure, has plenty to eat and drink, and lives to amuse himself.

Many Buddhist scholars imply that Buddha’s references to Mara are mere figures of of speech (1); but the Buddhist texts do not necessarily imply anything of the sort. In Theravada countries, veneration of good spirits, the placation of evil spirits, and Consulting Mediums are characteristic Buddhist practices. For example, the Burmese hang a coconut tied with a bit of red cloth near their home altars as an offering to the spirits. Special dances are also performed during the winter harvest season, during which a participant becomes “possessed” by spirits in order to bless the crops, while some participate in diviniation by Casting Bones Even so, the following should be remembered:

The Buddha said that neither the repetition of scriptures, nor self-torture, nor sleeping on the ground, nor the repetition of prayers, penances, hymns, charms, mantras, incantations and invocations can bring the real happiness of Nirvana. Instead the Buddha emphasized the importance of making individual effort in order to achieve spiritual goals.(source)

Buddhist texts, through inference, may suggest the possibility of a specific, living prince of evil; but Budhist writers take pains to point out it has no Adam and Eve story and no doctrine of original sin. Yet for Buddhists, the present state of human existence is “fallen” in that men are caught in a web of illusion, and long for liberation. Even though, according to Buddhist theory, men have not inherited the guilt flowing from an original sin, they are still trapped in a present state of suffering as result of evil committed in numerous past lives. Buddhism and Christianity agree that man is far from what he should be and his world is subject to the control of a malicious spirit, a powerful king of desire.

In India, prior to the advent of Buddhism, Mara was a God of Love in Vedic mythology. His name is in the language of Sanskrit and literally means death. He is a God of both Sex and Death. It is the act of love that brings a person into the world and death terminates a person. Thus, this god of death and love could be interpreted as a symbol for samsara, the cycle of birth, death and rebirth. By conquering Mara the Buddha is in effect conquering samsara. Occasionally, he is refered to as the Prince of Darkness in Buddhism. See also Kali Ma as well as the Shaman spiritual entity and sometime foe similar to Mara to the Buddha called the Ally.

One could interpret Mara as representing an ‘Anti-Buddha’ — as the opposite of everything the Buddha represents, “the enemy of the Good Law.” Buddhism advocates the Middle Path in between indulgence and asceticism, while Mara is a representative of the carnal pleasures. The Buddha stands for the end of death while Mara is death. Mara is violent. Sakyamuni Buddha is peaceful.

Early on the full moon day of Kason (April) in the year 103 of the Great Era, that is, some 2551 plus years ago, the now emaciated prince sat beneath the Bodhi Tree near the big village of Senanigãma. Around the same time, Sujãtã, the daughter of a rich man from the village, was making preparations to give an offering to the tree-spirit of the Bo tree. She had sent her maid ahead to tidy up the area around the spread of the holy tree, but at the sight of the starving man seated beneath the tree the maid thought the deity had made himself visible to receive their offering in person. She ran back in great excitement to inform her mistress. Sujãtã went to the tree and gave the prince nourishment in the form of a rice-milk gruel (Madhupayasa), inturn from which, the future Buddha regained his strength and health.

Prince Siddhartha began to eat the food beneath the shadow of the tree, sitting in a meditative mood underneath the tree from early morning to sunset, with a fiery determination and an iron resolve: “Let me die. Let my body perish. Let my flesh dry up. I will not get up from this seat till I get full illumination”. He plunged himself into deep meditation. At night he entered into Deep Samadhi.

The to-be Buddha’s encounter with Mara begins with that meditation. The possibility of Siddhartha becoming a Buddha and being liberated from the Earthly realm was not something that Mara desired. Mara decided to lure Shakyamuni away from his quest for Awakenment. He beseeched the Prince to follow his duties of father, ruler and husband and to abandon the quest for liberation from the material world. It is not proper for a king to renounce the world that he rules. The best life, Mara claimed, is to “subdue the world both with arrows and with sacrifices, and from the world obtain the world of Vsava.” Mara threatened the Prince with his bow and arrow stating that he spares those who indulge in carnal pleasures. Even when the arrow was shot, Sakyamuni stirred not. After failing to lead Gautama to the path of sensual gratification Mara utilized fear in his attempt to make Sakyamuni run away from the search for liberation. Mara gathered his fiendish minions from the deepest pits to wage war with Prince Siddhartha. The ten chief Sins, the Daughters of Mara first, then the remaining children of Mara, were sent into the fray:

- Sakkaya-ditthi is translated as “personality belief”. Conceit, arrogance, pride.

- Vicikiccha means “skeptical doubt’ about the Buddha, the Dhamma, the Sangha.

- Silabbataparamasa means “adherence to wrongful rites, rituals and ceremonies.” The Dark Sorceress.

- Kama-raga means temptation, “sensual desire,” Tanha, one of the three daughters of Mara. One of The Three Poisons.

- Patigha: ill will, including feelings of hatred, anger, resentment, revulsion, dissatisfaction, aversion, annoyance, disappointment. Arati, one of the three daughters of Mara. As hatred, another of The Three Poisons.

- Rupa-raga is “attachment to the form realms,” binding ourselves to Samsara; Raga, lust, one of the three daughters of Mara.

- Arupa-raga is “attachment to the formless realms.”

- Mana “conceit, arrogance, self-assertion or pride, feeling oneself to be superior to others.

- Uddhacca, self-righteousness, “restlessness,” agitation of the heart, turmoil of mind.

- Avijja is translated as ignorance and delusion, especially of the Four Noble Truths. As ignorance, the last of The Three Poisons.

After each Sin failed in subverting Shakyamuni, Mara sent forth the Lords of Hell from a thousand Limbos. The weather was turbulent, the power of Chaos, Hun-tun, mirroring the anarchic behaviour of the demons and the turmoil of the conflict. See also The Ten Fetters of Buddhism.

- For other uses see Mara.

In Buddhism, Mara is the demon who tempted Gautama Buddha by trying to seduce him with the vision of beautiful women who, in various legends, are often said to be his daughters. In Buddhist cosmology, Mara personifies unskillfulness, the “death” of the spiritual life. He is a tempter, distracting humans from practicing the spiritual life by making the mundane alluring or the negative seem positive.

The early Buddhists, however, rather than seeing Mara as a demonic, virtually all-powerful Lord of Evil, regarded him as more of a nuisance. Many episodes concerning his interactions with the Buddha have a decidedly humorous air to them.

In traditional Buddhism four senses of the word “mara” are given.

- Klesa-mara, or Mara as the embodiment of all unskilful emotions.

- Mrtyu-mara, or Mara as death, in the sense of the ceaseless round of birth and death.

- Skandha-mara, or Mara as metaphor for the entirety of conditioned existence.

- Devaputra-mara, or Mara the son of a deva (god), that is, Mara as an objectively existent being rather than as a metaphor.

Early Buddhism acknowledged both a literal and “psychological” interpretation of Mara. Mara is described both as an entity having a literal existence, just as the various deities of the Vedic pantheon are shown existing around the Buddha, and also is described as a primarily psychological force - a metaphor for various processes of doubt and temptation that obstruct religious practice.

“Buddha defying Mara” is a common pose of Buddha sculptures. The Buddha is shown with his left hand in his lap, palm facing upwards and his right hand on his right knee. The fingers of his right hand touch the earth, to call the earth as his witness for defying Mara and achieving enlightenment. This posture is also referred to as the ‘earth-touching’ mudra.

6. Describe the battle with all the weapons Maara used.

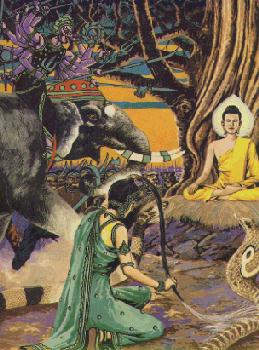

The Bodhisatta takes his seat upon the “bodhi seat” of grass; at night Mara brings his army to drive him from his quest

The event depicted in this picture is called “Mara’s challenge.” It occurred on the day of the full moon of the sixth lunar month, not many hours before the Buddha’s enlightenment. The sun was just setting behind the trees. The four-legged creature making as if to gore the Great Being is known as Naragirimekhala, the elephant of King Vassadi Mara, the commander of the army. The woman who is squeezing her hair is “Mother Earth,” Sundharivanida.

Mara had already confronted the Great Being once before, when he was just leaving the city gates on his great going forth, but this time the confrontation was the greatest of all Mara’s attempts to overthrow the Buddha. The army assembled by Mara on this occasion was of such size that the entire earth and sky were darkened by it. It came in from the sky, from across the earth and from beneath the earth, and was so fearsome that the devas that were guarding the Great Being all fled in terror to their palaces.

The Pathamasambodhi described the scene of Mara’s army thus: “… some of the beings had red faces and green bodies, some had green faces and red bodies; some of them manifested as white bodies with yellow faces … some of them had striped bodies and black faces … some of them had serpent lower bodies and human upper bodies …”

As for Mara, he appeared with a thousand arms on each side, each arm brandishing a different weapon-swords, spears, bows and arrows, javelins, wheel blades, hooks, maces, rocks, spikes, hatchets, axes, tridents, and more.

The reason that Mara confronted the Great Being on many occasions was that he hated to see anyone excelling him. Thus, since the Great Being was making efforts to be the “best” person in the world, he opposed him. But he always lost. On this occasion, he was defeated in the first round, so he tried some trickery, accusing the Great Being of usurping his seat, the “bodhi” seat, which he claimed to be his. Mara named as witnesses members of his own entourage. On his part, the Great Being could find no witnesses to support him, the devas having all fled, so he stretched out his right hand from under his robe and pointed his finger to the earth, upon which Mother Earth rose up to be his witness.

All of the above is an allegorical account. Its meaning will be given in the next chapter.

7. What is the spiritual significance of this battle?

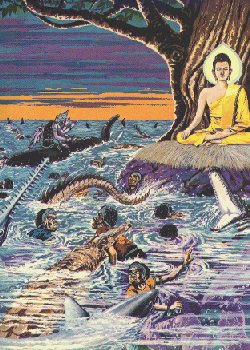

Mother Earth squeezes her hair, making a great ocean which sweeps away Mara’s armies

The place at which the Great Being sat in order to carry out his training of the mind and seek enlightenment, the foot of the bodhi tree, is called the “Throne of Awakenment.” Mara tried to claim that it was his own, but the Great Being countered that it had arisen as a result of the accumulated perfections of his previous lives, for which he called Mother Earth to witness.

The Pathamasambodhi states: “The great earth was incapable of remaining inactive … It sprang up from the earth in the form of a young maiden…” and served as witness for the Bodhisatta. Thereupon, [the maiden] squeezed water from her hair. That water is referred to as daksinodaka, which is all the water that the Great Being had used to consecrate the vows made in his previous lives, which Mother Earth had kept in her hair. When she squeezed her hair, all that water flowed out.

The Pathamasambodhi states: “It was a great flow that flooded all the land, like a great ocean…. The armies of Mara were powerless to stop it and were swept away and entirely carried off by the current. As for Girimekhala, Vassavadi Mara’s elephant, it was swept off its feet and, unable to maintain its balance, was carried off to the ocean. …Thus Mara was eventually defeated.”

Now I will explain the meaning of this allegory. Mara is the defilements within people; they are what opposes the mindfulness and understanding that lead to knowledge of good, evil, benefit and harm. Defilements take delight in misdeeds, so that when a person is going to do something good the defilements try to interfere. Before the Great Being was enlightened as the Buddha, he still had defilements, but they were in the process of falling from his mind. His defilements were the fondness and attachment for his royal treasures and the country he had left behind, but he was able to defeat them due to the great perfections [paramita] he had accumulated.

A perfection is goodness. The Great Being reflected that the lives, hearts and eyes he had sacrificed to others as wholesome deeds of charity, if gathered together, would be greater than the fruits in the forest and greater than the number of stars in the sky.

Good deeds do not disappear: even if no one sees them, the sky and the earth, Mother Earth, see them

8. What weapon did the Bodhisatta use with devastating effect against the infinitely superior forces of Maara?

9. Describe the scene of victory of the Bodhisatta, with the gods assembling from around and proclaiming his victory and defeat of Maara.

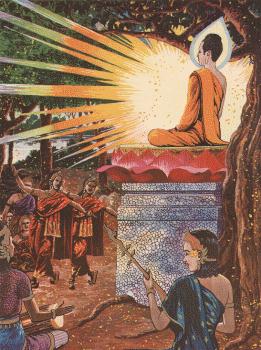

Devas from all the celestial realms convene to invite the Bodhisatta to take rebirth in order to become awakened as the Buddha

When the Bodhisatta Vessantara passed away he was reborn, just a little before the birth of the Buddha, in the Dusita deva realm. Devas of the many different realms convened to discuss who would become the awakened Buddha. They all agreed that the Bodhisatta residing in the Dusita heaven would be so awakened, and accordingly invited him to leave (cuti) the deva world and take birth [in the human realm] in keeping with his vow, in accordance with which all the perfections he had developed throughout countless lifetimes were for no other purpose than the attainment of Buddhahood.

The Buddha is awakened at dawn; the devas dance in his honor

By the time the Bodhisatta had conquered Mara, the sun was setting and night was falling. The Great Being sat motionless on his bodhi seat underneath the bodhi tree. He began to make his mind concentrated through the method known as jhana, absorption concentration, and attained nana.

Jhana is a method of concentrating the mind, making it one-pointed, not thinking restlessly of this and that as people ordinarily do. Nana is gnosis, clear realization. It may be simply illustrated thus: the still light of a candle in a windless room is like jhana, while the illumination from the candle is gnosis (nana).

The Great Being attained the first realization (nana) in the first watch of the night (about nine PM). The first nana is called “pubbenivasanusatinana,” meaning clear realization of the past lives of both oneself and others. During the middle watch of the night (about midnight) he attained the second nana, known as cutupapatanana, meaning, clear realization of the passing away and arising of beings in the world, and their differences due to kamma. In the last watch of the night (after midnight), he attained the third nana, known as asavakkhayanana, meaning clear realization of the extinction of defilements and the Four Noble Truths: suffering, the cause of suffering, the cessation of suffering and the way leading to the cessation of suffering.

The Great Being’s attainment of these three nana is known as his enlightenment as the Buddha, which occurred on the full moon night of the sixth lunar month. From this point on, the names “Siddhattha” and “Bodhisatta,” and the term “Great Being” newly coined before his enlightenment, all become things of the past, because from this point on he is known as arahantasammasambuddha, one who has on his own become enlightened and transcended all defilements.

This event is thus a great miracle. The poet has allegorized the episode in the Buddha’s honor by stating that at that time all animals, people, and devas throughout ten thousand world systems were relieved of their suffering, sorrow, despair and danger, and all beings were imbued with goodwill to each other, free of enmity and hatred.

All the devas played music, danced and sang the Buddha’s praises as an act of reverence and honor to the Buddha’s virtues.

Mara in the Buddhist tradition can be best understood as Satan, who always tried to dissuade the Buddha or any one from the righteous path. He is also called ‘Namuchi’ as none can escape him (Namuci iti Maro); and ‘Vasavatti’ as he rules all (Maro nama Vassavati sabbesam upari vasam vattati).< ?XML:NAMESPACE PREFIX = O />

When Gotama renounced the world and passed through the city gates on his horse Kanthaka, Mara appeared before him and tempted him by the offer to make him a universal monarch in seven days, if he was to change his mind. Siddhattha, however, did not pay any attention to him.

Mara and his army attacking the Buddha

Mara riding on his elephant Girimekhala to attack the Buddha with his army

The origin of the legend of Mara is first noticeable in the Padhana Sutta (See Samyutta Nikaya vs.425-49). His ten-fold army is Lust; Aversion; Hunger; Thirst; Craving; Stoth and Torpor; Cowardice; Doubt; Hypocrisy and Stupidity; False Glory; and Conceit. He has three daughters, Tanha, Arati and Raga representing the three out of the ten forces of Mara’s army. These daughters were employed to tempt the Buddha after his Enlightenment; and they could assume numerous forms of varying age and charm.

The Buddhavamsa Commentary and Nidanakatha of the Jataka commentary, particularly in the Singhalese versions, unfold a very lively and detailed account of the Mara’s visit to the Buddha just before his Enlghtenment, when he was sitting under the Bodhi tree. Seeing Gotama seated with a firm resolve to become a Buddha, he summoned all his forces to attack Sakyamuni. The forces extended twelve leagues in front and back; and nine leagues on right and left. Mara himself with thousand arms riding on his elephant Girimekhala, attacked Gotama. His followers armed with deadly weapons and assuming various frightening forms joined him in his attack. The Devas, Nagas, and others who had gathered round Gotama to pay him homage and sing his praises then fled at the sight of the frightening army of Mara. The Bodhisatta then called the ten paramis, which he had perfected in various births, for his defense. Each of the ten divisions of Mara’s army was then defeated and routed by one parami. Eventually, Mara’s army had to flee. Vanquished Mara then hurled his last weapon – the chakkavudha (disc), which stood over the Bodhisatta’s head like a canopy of flowers. Still Mara tried to dissuade Gotama from the path of the Buddhahood by falsely claiming the Gotama’s seat as his own; and by asking him to prove his right to the seat on which he was sitting. All the Mara’s followers then testified Mara’s claim by shouting that the seat actually belonged to Mara. As the Bodhisatta had no other witness to bear testimony on his behalf he asked the Earth to speak for him by touching the ground with his middle finger. The Earth then roared in response and bore the testimony for the Bodhisatta by thundering, “I stand his witness”. Thus, the Mara’s defeat was final; and he and his followers had to flee. The Devas and other celestial beings then besieged him and celebrated his victory.

The Buddha and the Mara’s army and his three daughters

The Buddha touches the ground with his fingers (bhumi-sparshan mudra) to ask the earth to bear

testimony for him to refute the Mara’s claim

10. Describe all the historic events, one after another, following the defeat of Maara, between a) the first watch between

Siddhattha - Life as a Prince and Renunciation - with meditation teachers - Practice of severe austerities - his meditation before Awakenment - the Three Knowledges - inspired verses after Awakenment- who to teach? The five ascetics - Añña Kondaññā, the first Arahant.

Prince Siddhattha, heir to the throne of the Sākiyan kingdom, saw, in spite of his father’s endeavours, old age, disease and death; and also a religious wanderer in yellow robes who was calm and peaceful. When he had seen these things, withheld from him until his early manhood, he was shocked by the sight of the first three realising that he also must suffer them, but he was inspired by the fourth and understood that this was the way to go beyond the troubles, and sufferings of existence. Though his beautiful wife, Yasodharā presented him with a son who was called Rāhula, he was no longer attracted to worldly life. His mind was set upon renunciation of the sense pleasures and uprooting the desires, which underlay them.

So at night he left behind his luxurious life and going off with a single retainer, reached the Sākiyan frontiers. There he dismounted from his horse, took off his princely ornaments and cut off his hair and beard with his sword. Then he changed into yellowish-brown patched robes and so transformed himself into a Bhikkhu or wandering monk. The horse and valuables he told his retainer to take back with the news that he had renounced pleasures and gone forth from home to homelessness.

At first he went to various meditation teachers but he was not satisfied with their teachings when he became aware that they could not show him the way out of all suffering. Their attainments, which he equalled, were like temporary halts on a long journey, they were not its end. They led only to birth in some heaven where life, however long, was nevertheless impermanent. So he decided to find his own way by bodily mortification. This he practised for six years in every conceivable way, going to extremes, which other ascetics would be fearful to try. Finally, on the edge of life and death, he perceived the futility of bodily torment and remembered from boyhood a meditation experience of great peace and joy. Thinking that this was the way, he gave up troubling his body, and took food again to restore his strength. So in his life he had known two extremes, one of luxury and pleasure when a prince, the second of fearful austerity, but both he advised his first Bhikkhu disciples, should be avoided.[1]

Having restored his strength, he sat down to meditate under a great pipal tree, later known as the Bodhi (Enlightenment) Tree. His mind passed quickly into four states of deep meditation called jhāna. In these, the mind is perfectly one-pointed and there is no disturbance or distraction. No words, no thoughts and no pictures, only steady and brilliant mindfulness. Some mental application and inspection is present at first along with physical rapture and mental bliss. But these factors disappear in the process of refinement until in the fourth jhāna only equanimity, mindfulness and great purity are left. On the bases of these profound meditation states certain knowledge arose in his mind.

These knowledge, which when they appear to a meditator are quite different from things which are learnt or thought about, were described by him in various ways. It is as though a person standing at various points on a track, which is roughly circular, should describe different views of the same landscape; in the same way the Buddha described his Bodhi or awakening experience. Some parts of this experience would be of little or no use to others in their training so these facts he did not teach. What he did teach was about dukkha or suffering, how it arises and how to get beyond it. One of the most frequent views into this ‘landscape of Awakenment’ is the Three Knowledges: of past lives, of kamma and its results, and of the destruction of the mental pollution.

The wisdom of knowing his own past lives, hundreds of thousands of them, an infinite number of them, having no beginning - all in detail with his names and occupations, the human, super-human and sub-human ones, showed him the futility of searching for sense-pleasures again and again. He saw as well that the wheel of birth and death kept in motion by desires for pleasure and existence would go on spinning for ever producing more and more of existence bound up with unsatisfactory conditions. Contemplating this stream of lives he passed the first watch of the night under the Bodhi Tree.

The wisdom pertaining to kamma[2] and its results means that he surveyed with the divine interior eye all sorts of beings, human and otherwise and saw how their past kammas gave rise to present results and how their present kammas will fruit in future results. Wholesome kammas, developing one’s mind and leading to the happiness of others, fruit for their doer as happiness of body and mind, while unwholesome kammas which lead to deterioration in one’s own mind and suffering for others, result for the doer of them in mental and physical suffering. The second watch of the night passed contemplating this wisdom.

In the last watch he saw how the pollution, the deepest layer of defilement and distortion, arise and pass away conditionally. With craving and ignorance present, the whole mass of sufferings, gross and subtle, physical and mental - all that is called dukkha, come into existence; but when they are abandoned then this burden of dukkha, which weighs down all beings and causes them to drag through myriad lives, is cut off and can never arise again. This is called the knowledge of the destruction of the pollutions: desires and pleasures, existence and ignorance, so that craving connected with these things is extinct.

When he penetrated to this profound truth, the arising and passing away conditionally of all experience and thus of all dukkha, he was the Buddha, Enlightened, Awakened. Dukkha he had known thoroughly in all its most subtle forms and he discerned the causes for it’s arising - principally - craving. Then he experienced its cessation when its roots of craving had been abandoned, this cessation of dukkha also called Nibbāna, the Bliss Supreme. And he investigated and developed the Way leading to the cessation of dukkha, which is called the Noble Eightfold Path. This Path is divided into three parts: of wisdom - Right View and Right Thought; of moral conduct - Right Speech, Right Action and Right Livelihood; of mind development - Right Effort, Right Mindfulness and Right Collectedness. It has been described many times in detail.[3]

We are told that to the Buddha experiencing the bliss supreme of Enlightenment the following two verses occurred:

-

„Through many births in the wandering-on

-

I ran seeking but finding not

-

the maker of this house -

-

dukkha is birth again, again.

-

-

O house maker, you are seen!

-

You shall not make a house again;

-

all your beams are broken up,

-

rafters of the ridge destroyed:

-

the mind gone to the Unconditioned,

-

to craving’s destruction it has come“.

-

(Dhammapada, verses 153-154)

Now that he had come to the end of craving and desire, a thing, so difficult to do, and after reviewing his freedom from the round of birth and death, he concluded that no one in the world would understand this teaching. Men are blinded by their desires, he thought and his mind inclined towards not teaching the Dhamma. Then with the divine eye he saw that there were a few beings „with little dust in their eyes“ and who would understand. First he thought of the two teachers he had gone to and then left dissatisfied but both had died and been reborn in the planes of the formless deities having immense life spans. They would not be able to understand about ‘arising and passing away’. Then he considered the whereabouts of the five ascetics who had served him while he practised severe bodily austerities. The knowledge came to him that they were near Benares, in the Deer-sanctuary at Isipatana; so he walked there by slow stages. So he began the life of a travelling Bhikkhu, the hard life that he was to lead out of compassion for suffering beings for the next forty-five years.

When the Buddha taught these five ascetics he addressed them as ‘Bhikkhus’. This is the word now used only for Buddhist monks but at that time applied to other religious wanderers. Literally, it means ‘one who begs’ (though Bhikkhus are not allowed to beg from people, they accept silently whatever is given. See Chapter VI). At the end of the Buddha’s first discourse[4], Kondaññā[5] the leader of those Bhikkhus, penetrated to the truth of the Dhamma. Knowing that he had experienced a moment of Enlightenment - Stream-winning as it is called, the Buddha was inspired to say, „Kondaññā truly knows indeed Kondaññā truly knows!“ Thus he came to be known as Añña-Kondaññā - Kondaññā who knows as it really is.