Insight Net - GRADI Online Tipiṭaka Riċerka u Prattika Università u

NEWS relatati permezz ta ‘http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org f’105 LINGWI

KLASSIĊI Paṭisambhidā

Jāla-Abaddha Paripanti Tipiṭaka Anvesanā ca Paricaya Nikhilavijjālaya

ca ñātibhūta Pavatti Nissāya http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org anto 105

Seṭṭhaganthāyatta Bhāsā huwa kanal tal-aħbarijiet onlajn

Ikel għal aktar minn 3000 Emails:

200 WhatsApp, Facebook u Twitter. https://dhammawiki.com/index.php/1-10_early_to_recent_Chronology_of_Pali_Canon https://dhammawiki.com/…/1-10_early_to_recent_Chronology_of …

1-10 kmieni għall-Kronoloġija reċenti ta ‘Pali Canon Thomas

William Rhys Davids fl-Indja Buddista tiegħu (p. 188) ta tabella

kronoloġika tal-letteratura Buddista mill-ħin tal-Buddha sal-ħin ta

‘Ashoka li huwa kif ġej: 1.

Id-dikjarazzjonijiet sempliċi tad-duttrina Buddista issa nstabu,

f’kelmi identiċi, f’paragrafi jew versi rikurrenti fil-kotba kollha. 2. Episodji misjuba, bi kliem identiċi, f’żewġ jew aktar mill-kotba eżistenti. 3. Il-Silas, il-Parayana, l-Octades, il-Patimokkha. 4. Il-Digha, Majjhima, Anguttara u Samyutta Nikayas. 5. Is-Sutta Nipata, it-Thera u Theri Gathas, il-Udanas, u l-Khuddaka Patha. 6. Is-Sutta Vibhanga, u Khandhkas. 7. Il-Jatakas u d-Dhammapadas. 8. Niddesa, Itivuttakas u Patisambbhida. 9. Il-Peta u Vimana-Vatthus, l-Apadana, il-Cariya-Pitaka, u l-Buddhavamsa. 10. Il-kotba Abhidhamma; l-aħħar waħda hija l-Katha-Vatthu, u l-aktar kmieni probbabilment il-Puggala-Pannatti. Dawk

elenkati fil-quċċata jew ħdejn il-quċċata, bħan-numri minn ħamsa sa

ħamsa, huma kkunsidrati bħala l-aktar testi qodma, eqdem u l-iktar

probabbli li jkunu awtentiċi u l-kliem eżatt tal-Buddha. It-testi

ta ‘wara u l-kummentarji u l-Visuddhimagga huma miżmuma bi stima għolja

ħafna mill-Theravada Klassika, filwaqt li t-Theravada Moderna tiffoka

fuq it-taghlim bikri tal-Buddha.

Theravada Moderna Artikolu prinċipali: Theravada Moderna Bhikkhu

Bodhi, Dhammavuddho Thera u oħrajn għandhom id-dubji tagħhom, kif

jagħmlu studjużi moderni dwar it-testi ta ‘wara u jekk huma Buddhavacana

(kliem eżatt ta’ Buddha) jew le. Theravadins Moderna probabilment għandhom varjetà żgħira ta ‘opinjonijiet iżda probabilment jieħdu waħda minn dawn li ġejjin: 1.

L-ewwel erba Nikayas fl-intier tagħhom huma Buddhavacana, flimkien

mal-kotba li ġejjin mill-Khuddaka Nikaya: Dhammapada, Udana, Itivuttaka,

Sutta Nipata, Theragatha u Therigatha; u l-Patimokkha mill-Vinaya. (Dan xorta jagħmel il-porzjon Buddhavacana tat-Tipitaka bejn wieħed u ieħor 30 minn 40 volum). 2.

Kollha ta ‘hawn fuq, flimkien mal-kotba l-oħra tal-Khuddaka Nikaya,

flimkien mal-kotba Vinaya oħra, flimkien mal-Abhidhamma, iżda jarawhom

kif miktub minn dixxipli posterjuri tal-Buddha, li setgħu kienu arahants

u għalhekk, xorta jistħoqqilhom inkluż fil-Canon, għalkemm mhux probabbli parti mill-Buddiżmu Oriġinali. Il-patrijiet

akkademiċi Ajahn Sujato u Ajahn Brahmali kitbu l-ktieb The Authenticity

of Early Buddhist Texts u huma jaqblu man-numru wieħed t’hawn fuq, li

jikkonsisti mill-ewwel 4 Nikayas u xi wħud mill-Nikka Khuddaka bħala

Buddhavacana. Ara wkoll: Buddiżmu Oriġinali

Referenzi Il-Ktieb sħiħ tal-Listi ta ‘Buddha - Spjegat. David N. Snyder, Ph.D., 2006.

http://www.thedhamma.com/

L-Awtentiċità tat-Testi Buddisti Bikrija Is-Soċjetà Buddista tal-2014.

https://suttacentral.net/

dhammawiki.com

1-10 kmieni għall-Kronoloġija reċenti ta ‘Pali Canon - Dhamma Wiki

Thomas

William Rhys Davids fl-Indja Buddista tiegħu (p. 188) ta tabella

kronoloġika tal-letteratura Buddista mill-ħin tal-Buddha sal-ħin ta

‘Ashoka li huwa kif ġej:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1K__1scyaiA

THE FIRST SERMON

Benoy Behl

Published on May 4, 2009

Category

Film & Animation

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=za0Df22bTL0

The Voice of the Buddha

Benoy Behl

Published on Jul 22, 2014

Film about the International Tripitaka Chanting and other activities of the Light of Buddhadharma Foundation.

Category

Film & Animation

Insight Net - Tipiṭaka Research Online me te Practice Wharerangi me nga

korero e pā ana mai i http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org i roto i te 105

WHAKANUI KAUPAPA Paṭisambhidā

Jāla-Abaddha Paripanti Tipiṭaka Anvesanā ca Paricaya Nikhilavijjālaya

ca ñātibhūta Pavatti Nissāya http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org anto 105

Seṭṭhaganthāyatta Bhāsā Ko te NEW NEW CHANNEL

Te mahi ki nga neke atu i te 3000 Miihini:

200 WhatsApp, Facebook me Twitter. https://dhammawiki.com/index.php/1-10_early_to_recent_Chronology_of_Pali_Canon https://dhammawiki.com/…/1-10_early_to_recent_Chronology_of…

1-10 i te tīmatanga o te Chronology o Pali Canon Ko

Thomas William Rhys Davids i roto i tana Buddhist India (p. 188) kua

hoatu he ripanga o nga pukapuka Buddhist mai i te wa o Buddha ki te wa o

Ashoka e penei: 1.

Ko nga korero o te whakaakoranga Buddhist kua kitea inaianei, i roto i

nga kupu rite, i roto i nga paraka, nga ira ranei e mau ana i roto i nga

pukapuka katoa. 2. I kitea nga pukapuka i roto i nga kupu rite, i roto i nga pukapuka e rua, neke atu ranei. 3. Ko Hira, ko Parayana, ko Octades, ko Patimokkha. 4. Ko Digha, Majjhima, Anguttara, me Samyutta Nikayas. 5. Ko te Sutta Nipata, ko Thera, ko Theri Gathas, ko Udanas, ko te Khuddaka Patha. 6. Ko te Sutta Vibhanga, ko Khandhkas. 7. Nga Jatakas me nga Dhammapadas. 8. Te Niddesa, te Itivuttakas me te Patisambbhida. 9. Ko te Peta me te Vimana-Vatthus, te Apadana, te Cariya-Pitaka, me te Buddhavamsa. 10. Ko nga pukapuka Abhidamama; ko te whakamutunga ko te Katha-Vatthu, ko te tuatahi ko Puggala-Pannatti. Ko

nga mea kua whakaruarangitia ki runga, e tata ana ranei ki runga, e

rite ana ki te tau kotahi ki te rima, ka whakaarohia ko nga timatanga,

ko nga tuhinga tawhito, me te mea pea he pono, me nga kupu tika a

Buddha. Ko

nga tuhinga o muri mai, me nga korero me nga Visuddhimagga, kei te tino

nui te ahua o te Classical Theravada, engari ko te Modern Theravada te

arotahi ki nga whakaakoranga tuatahi a Buddha.

Modern Theravada Tuhinga matua: Modern Theravada Ko

Bhikkhu Bodhi, ko Dhammavuddho Thera me etahi atu he ruarua, he rite

hoki nga tohunga hou mo nga tuhinga o muri mai, me te mea he

Buddhavacana (nga kupu tika o Buddha), ehara ranei. He maha nga whakaaro o te Theravadins Modern kaore pea e whai ake nei: 1.

Ko Nikayas tuatahi tuatahi ko Buddhavacana, me nga pukapuka e whai ake

nei mai i te Khuddaka Nikaya: Dhammapada, Udana, Itivuttaka, Sutta

Nipata, Theragatha, me Therigatha; me te Patimokkha i te Vinaya. (Ka waiho tonu te waa Buddhavacana o te Tipitaka i te 30 o nga 40 o nga pukapuka.) 2.

Ko nga mea katoa o runga ake, me era atu pukapuka o te Khuddaka Nikaya,

me era atu pukapuka Vinaya, me te Abhidhamma, engari ka kite ia ratou i

tuhia e nga akonga o muri mai o te Buddha, he tangata kua awhina, me te

mea he tika tonu kia waiho hei kei roto i te Canon, ahakoa kaore he waahanga o te Buddhism taketake. Kua

tuhia e te karauna moemoea Ajahn Sujato me Ajahn Brahmali te pukapuka

Ko te Pono o nga Pukapuka Buddhist Early, a he rite ki te tau kotahi i

runga ake, ko te Nikayas tuatahi me etahi o nga Khuddaka Nikaya ano ko

Buddhavacana. Titiro hoki: Ko te Buddhism taketake

Nga korero Ko te Puka Tuhituhi o nga Pukapuka a Buddha - Kua Whakamahia. David N. Snyder, Ph.D., 2006.

http://www.thedhamma.com/

Ko te Motuhake o nga Pukapuka Buddhist Early Buddhist Publication Society, 2014.

https://suttacentral.net/

dhammawiki.com

1-10 i te tīmatanga o te Chronology o Canon Canon - Dhamma Wiki

Ko

Thomas William Rhys Davids i roto i tana Buddhist India (p. 188) kua

hoatu he ripanga o nga pukapuka Buddhist mai i te wa o Buddha ki te wa o

Ashoka e penei:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OO8nE–a5yg

Traditional Tattoos: Fang Od and Kalinga Tattooing in the Philippines

Wade Shepard

Published on Jan 8, 2014

My gear:

Big camera: http://amzn.to/2hHXIVb

Small camera: http://amzn.to/2zpLFnA

Drone: http://amzn.to/2ieAGsW

Gimbal camera: http://amzn.to/2hIirIk

Action cam: http://amzn.to/2xIkoj3

Favorite lens: http://amzn.to/2yqRJhC

Sound recorder: http://amzn.to/2kO17X6

Fang Od is part of the last line of traditional Kalinga tattoo artists

in the Philippines. It was assumed for a while that the now 93 year old

Fang Od would be the last, but her granddaughter has taken up the art

and the traditional continues. This type of authentic tribal tattooing

was once done for head hunters and to beautify women, who would be able

to take their tattoos with them in the after life. Find out more about

traditional Kalinga Philippines tattooing at http://www.vagabondjourney.com/fang-o….

To purchase full resolution clips of this video contact Vagabondsong [at] gmail.com

“Vagabond Journey: A Global Nomad Since 1999″

Subscribe to channel: http://tinyurl.com/subscribe-vagabond…

Visit site: http://www.vagabondjourney.com

Follow Vagabond Journey:

Subscribe: http://www.vagabondjourney.com/feed/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/vagabondjour…

Twitter: https://twitter.com/vagabondjourney

Google Plus: https://plus.google.com/u/0/+WadeShepard

Pinterest: http://www.pinterest.com/vagabondjour…

LinkedIn: http://www.linkedin.com/in/wadeshepard

Category

Travel & Events

इनसाइट नेट - विनामूल्य ऑनलाइन टिपिका रिसर्च अँड प्रॅक्टिस युनिव्हर्सिटी

आणि संबंधित न्यूज: http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org वर 105 क्लासिक

भाषांमध्ये पिसिम्भदा

जाल-अबपा पिपंती टिपिका अवेसाणा सीए परिकया निखिलविजलया सी एन टीभुवत

पवत्ती निसाया http://svajan.ambedkar.org anto 105 संथागत्य भासा एक ऑनलाईन वृत्तपत्र आहे

3000 पेक्षा जास्त ईमेल्ससाठी कॅटरिंग:

200 व्हाट्सएप, फेसबुक आणि ट्विटर https://dhammawiki.com/index.php/1-10_early_to_recent_Chronology_of_Pali_Canon https://dhammawiki.com/…/1-10_early_to_recent_Chronology_of…

पाली कॅननच्या कालखंडातील आपल्या

बौद्ध भारत (थॉमस 188) मध्ये थॉमस विल्यम राईस डेव्हिड्स यांनी बुद्धकालीन

काळापासून अशोकच्या काळातील बौद्ध साहित्याचा कालानुक्रमिक टेबल दिला आहे: बौद्ध सिद्धांतातील साध्या विधाने आता सर्व पुस्तकात पुनरावृत्त परिच्छेद किंवा अध्याय मध्ये समान शब्दांत आढळतात. 2. एपिसोडचे दोन किंवा त्यापेक्षा जास्त पुस्तके एकसारखे शब्द आहेत. 3. सिलास, परिण, ऑक्टेट्स, पाटीमोक दिघा, माजजिमा, अंगुत्तारा आणि समुत निकय्या. 5. सुत्ता निपत, थेरा आणि थेरथ, आठवत, आणि खुडका पथ. 6. सुत्त विभंगा व खांडके. 7. जटाका आणि धम्मपदास. 8. निदेशास, इतिवत्तकास आणि पतिसंबभड्डा 9. पेटा आणि विमन-वत्थस, अपदाना, करिया-पितका आणि बौद्धवंसा. 10. अभिनव पुस्तके; जे शेवटचे आहे ते कथा-वाथू, आणि सर्वात आधी कदाचित पुगल-पन्नट्टी. शीर्षस्थानी

किंवा शीर्षस्थानी सूचीबद्ध केलेले, जसे की संख्या एक ते पाच, हे सर्वात

जुने, जुने ग्रंथ समजले जातात आणि ते प्रामाणिक असण्याची आणि बुद्धांच्या

अचूक शब्दांची जास्त शक्यता असते. नंतरचे

ग्रंथ आणि टीपा आणि विसचिहिमग्गा हे प्राचीन थिवाडाने अतिशय आदराने ठेवले

आहेत, तर आधुनिक थिवाडांनी बुद्धांच्या सुरुवातीच्या शिकवणींवर लक्ष

केंद्रित केले आहे.

आधुनिक थेरवडा मुख्य लेख: आधुनिक थेरवाद नंतरच्या

ग्रंथांविषयी आधुनिक विद्वान म्हणून भिक्खु बोधी, धम्मुंदु थ्रा आणि

इतरांच्या मनात शंका आहेत आणि जर ते बुद्धवचन आहेत (बुद्धांच्या अचूक शब्द)

किंवा नाहीत तर आधुनिक Theravadins कदाचित मते एक किंचित विविध धारण पण कदाचित खालील पैकी एक घेऊन: 1.

त्यांच्यातील पहिले चार नाकाय हे बुद्धवचन आहेत, तसेच खालील पुस्तके

खादुका निकियामा: धम्मपद, उदाना, इतिवत्तक, सुत्ता निपाता, थरगाथा, आणि

थेरिथा आहेत. आणि विन्याकडून पाथीमक्षी. (तरीही 40 खंडांतील 30 पैकी तिप्पटकाचा बौद्धकानाचा भाग तयार होईल.) 2.

वरील पैकी सर्व, तसेच खुद्दका निकयच्या इतर पुस्तके, तसेच इतर विनय

पुस्तके, अभिधमम्, परंतु त्यांना बुद्धांच्या नंतरच्या अनुयायांनी लिहिलेली

पहात आहेत, जे अरहाण ठरले आहेत आणि अशा प्रकारे ते अद्याप योग्य आहेत मूळ बौद्ध धर्माचा भाग नसला तरी तो कॅननमध्ये समाविष्ट झाला. विद्वान

महासत्ता अजहन सुजातो आणि अजहन ब्रह्माली यांनी ‘द प्रामाणिकिटी ऑफ अर्ली

बौव्हिस्ट ग्रंथ्स’ हे पुस्तक लिहिलं आहे आणि ते पहिल्या क्रमांकावर

असलेल्या 4 निकेय आणि काही खुद्दाक निकशा यांच्याकडे बौद्धकन म्हणून

समाविष्ट आहेत. हे देखील पहा: मूळ बौद्ध धर्म

संदर्भ बुद्धांच्या सूचीची पूर्ण पुस्तक - स्पष्ट डेव्हिड एन. स्नायडर, पीएच.डी., 2006.

http://www.thedhamma.com/

बौद्ध प्रकाशन सोसायटी, 2014 मधील प्रारंभिक बौद्ध ग्रंथांचे सत्यत्व.

https://suttacentral.net/

धम्मॉमी. com

1 9 1-10 च्या सुरुवातीस अलीकडील कालवाली पाली कॅनन - धम्म विकी

आपल्या

बौद्ध भारत (थॉमस 188) मध्ये थॉमस विल्यम राईस डेव्हिड्स यांनी बुद्धकालीन

काळापासून अशोकच्या काळातील बौद्ध साहित्याचा कालानुक्रमिक टेबल दिला आहे:

Buddha’s original words in Classical Marathi

Buddha life story in Marathi

Harshavardhan Devde

Published on Aug 16, 2015

Category

Nonprofits & Activism

https://www.thesun.co.uk/tech/3800248/what-is-gif-how-pronounced-animated-memes/

What is a GIF, who invented the image format, how is it pronounced and what’s an animated meme?

From

its humble beginnings on black and white computers to its now

ubiquitous usage in memes and how Facebook is celebrating the GIF’s

birthday

THE GIF turned 30 today, so, let’s wish the Graphical Interchange Format a very happy birthday.

From its humble beginnings on black and white computers to its now

ubiquitous usage in memes, we have the lowdown on one of the most

important file formats in history.

What is a GIF?

A GIF, or Graphical Interchange

Format, is a bitmap image format that was invented on June 15 1987 by a

US software writer called Steve Wilhite for CompuServe.

Gifs are highly compressed images that typically allow up to 8 bits

per pixel for each image, which in total allow up to 256 colours across

the image.

For comparison, a JPEG image can display up to 16 million colours and pretty much reaches the limits of the human eye.

Back when the internet was new, gifs were used extensively because they didn’t require much bandwidth.

Check out the original Space Jam website from 1996, pictured above - it still works!

How do you pronounce GIF?

This is probably one of the most important questions that you could ever have asked Jeeves.

Without any further adieu, the creators of the gif pronounced the word as “jif”, with a soft g like that in “gin”.

According to Steve Wilhite, he intended it to sound like the American brand of peanut butter, Jif.

If only it was that simple - the pronunciation with a hard G as in

“gift” is listed by the Cambridge Dictionary of American English as the

correct pronunciation, whilst the Oxford English Dictionary lists both

pronunciations as correct.

Saying gif with a hard g is also widely used across the English

speaking world and it would seem that people pronounce it based on

personal preference.

This eternal disagreement has lead to heated debates across the

Internet and it doesn’t seem like an argument that will ever go away.

What are animated GIFs?

A single gif file can feature multiple frames which are displayed in

succession in order to create an animated clip, these can either be

looped endlessly or just stop at the end of the sequence.

We tend to use animated gifs today as “Reaction Gifs”, they act as

fun replies for conversations on apps like Facebook Messenger.

Animated gifs are one of the most common image formats on the

Internet and now you can find the perfect gif for any topic using

websites like Giphy.

So instead of replying to your ex with a sad face emoji, or words

like a regular human being, you can just send them a gif of Zooey

Deschanel instead.

But they can also be used to create amazing pieces of art in the form of the Cinemagraph, coined and created by husband and wife duo Jamie Beck and Kevin Burg.

Across a static image they create individual instances of motion

which ultimately creates moments of eloquence and peacefulness, turning

the humble gif into something that could be profound or meaningful.

What about memes?

The main difference between an animated gif and a meme is that memes

tend to be static images that make a topical or pop culture reference

and animated gifs are, more simply, moving images.

You can find all the animated gif memes that your heart desires at website such as Giphy and Awesome Gifs.

As with most things, gifs and memes work better together. Grab an

animated gif and stick some topical words on it et voilà, you have an

animated meme.

How did Facebook celebrate the GIF’s birthday?

To mark the GIF turning 30, Facebook has added new GIF related services to the social media platform.

Users could already post GIFs in status updates, but from today they can also use them in comment threads.

Happy birthday GIF.

68) Classical Mongolian

68) Сонгодог монгол хэл

2650 Өнгөрсөн 13-р сар LESSON

Одоо

Аналитик

Insight Net - Онлайн Татварын Товчоо ба Практикийн Их Сургууль ба

холбогдох МЭДЭЭЛЭЛ http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org хаягаар 105 CLASSICAL

LANGUAGES

Паṭисамбхада

Жаяа-Абаддха Парипванти Тутсүхака Анушана Парикаяа Никилавъямалала ва

ѐнтуша Паватти Нисяяа http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org anto 105

Сүнтхарянятта Бхакса

Онлайн Мэдээ суваг

3000 гаруй И-мэйлээр үйлчлэх:

200 WhatsApp, Facebook болон Twitter.

https://dammammiki.com/index.php/1-10_early_to_recent_Chronology_of_Pali_Canon

https://dhammawiki.com/…/1-10_early_to_recent_Chronology_of…

Пали Канонын дараалал

Буддын

Энэтхэгийн Томас Уильям Рис Дэвид (188-р хуудас) нь Бурхан багшийн үеэс

Ашока хот хүртэлх буддын ном судруудын он цагийн дарааллыг өгчээ.

1. Одоогийн Буддын шашны сургаалын энгийн өгүүлбэрүүд нь ижил төстэй үгс, бүх номонд гарч буй догол мөр эсвэл шүлэгт байдаг.

2. Хичээлийн хоёр буюу түүнээс олон номнууд ижил төстэй үг олдсон.

3. Силас, Паранаа, аравдугаар сар, Патимокка.

4. Дилаа, Мажжима, Анутара, Самуата Никая нар.

5. Сатта Нипата, Тера, Тери Гатас, Уданас, Хаддака Пата нар.

6. Сатта Вибхана, мөн Хандарка.

7. Жатакас ба Дэммамбадууд.

8. Ниддеша, Йитттхакка ба Патисамббида нар.

9. Газрын зураг, Вимана-Ваттус, Ападана, Кэрия-Питака, Буддавама нар.

10. Абидраммын номууд; Хамгийн сүүлийн нь Ката-Ватту, хамгийн эртний нь Puggala-Pannatti юм.

Жишээ

нь, нэгээс тав хүртэлх тооны дээд талд буюу дээд талд байрласан тэдгээр

хүмүүс бол хамгийн эртний, хамгийн эртний эх бичвэрүүд бөгөөд Буддын

жинхэнэ үгс, хамгийн үнэн үг байж магадгүй юм. Сүүлд

бичсэн текстүүд, тайлбарууд болон Вишүддхрэнга нь сонгодог Теравадагаас

маш их үнэлэгддэг бол орчин үеийн Теравада нь Буддагийн эртний сургаал

дээр төвлөрдөг.

Орчин үеийн Теравада

Гол өгүүлэл: Орчин үеийн Теравада

Бхавхи

Бххи, Дмамамдддхо Тха болон бусад шавь нар нь эргэлзээтэй байдаг. Орчин

үеийн эрдэмтдийн адил хожмын бичгүүдийн тухай, Буддавакана (Буддагийн

яг тодорхой үгс) гэх мэтээр эргэлздэг. Орчин үеийн Теравадинууд бага зэрэг янз бүрийн санал бодолтой байж магадгүй ч дараах зүйлсийн аль нэгийг нь авч болно:

1.

Эхний дөрвөн Никая нь бүхэлдээ Буддавакана бөгөөд Хаддака Назаяагийн

дараахь номуудыг багтаасан: Dhammapada, Udana, Itivuttaka, Sutta Nipata,

Theragatha, Therigatha; мөн Ватаяаас Патимокка. (Энэ нь Типитака-гийн буддавакana хэсгийг 40 ширхэгээс 30 орчим болгоно)

2.

Дээр дурдсан бүхэн, Khuddaka Nikaya-ийн бусад ном, бусад Vinai номууд,

дээр нь Абхидхамма гэхээс гадна Буддагийн дагалдагчдын бичсэнээр

тэдгээрийг харж болно. Canon-д багтдаг боловч Буддизмын анхных нь биш байж болох юм.

Шинжлэх

ухааны эрдэмтэн Ахаха Судато, Ачах Брахмали нар Буддын эртний судруудын

бичсэн номыг бичсэн бөгөөд тэд эхний 4 Никая болон зарим Хаддака Никаяа

буддава гэж бичигдсэн байдаг.

Эх сурвалж: Бурханы шашин

Лавлагаа

Бурханы шашны номнуудын бүрэн жагсаалт - Тайлбарласан. Дэвид Н.Снайдер, Доктор, 2006.

http://www.thedhamma.com/

Бурханы шашны хэвлэн нийтлэлийн нийгэмлэг, Буддын ном хэвлэлийг 2014 онд баталсан.

https://suttacentral.net/

dhammawiki.com

Пали Канадын он дарааллын 1-10-р эрт эхээр - Dhamma Wiki

Буддын

Энэтхэгийн Томас Уильям Рис Дэвид (188-р хуудас) нь Бурхан багшийн үеэс

Ашока хот хүртэлх буддын ном судруудын он цагийн дарааллыг өгчээ.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=phjaV3pAcek

Filial piety of twenty-one Dari Ekh (bodhisattva) - (Mongolian Buddha Song)

Speed of Light

Published on Oct 27, 2015

Category

Music

68) Classical Mongolian

68) Сонгодог монгол хэл

Insight Net - Онлайн Татварын Товчоо ба Практикийн Их Сургууль ба

холбогдох МЭДЭЭЛЭЛ http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org хаягаар 105 CLASSICAL

LANGUAGES Паṭисамбхада

Жаяа-Абаддха Парипванти Тутсүхака Анушана Парикаяа Никилавъямалала ва

ѐнтуша Паватти Нисяяа http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org anto 105

Сүнтхарянятта Бхакса Онлайн Мэдээ суваг

3000 гаруй И-мэйлээр үйлчлэх:

200 WhatsApp, Facebook болон Twitter. https://dammammiki.com/index.php/1-10_early_to_recent_Chronology_of_Pali_Canon https://dhammawiki.com/…/1-10_early_to_recent_Chronology_of…

Пали Канонын дараалал Буддын

Энэтхэгийн Томас Уильям Рис Дэвид (188-р хуудас) нь Бурхан багшийн үеэс

Ашока хот хүртэлх буддын ном судруудын он цагийн дарааллыг өгчээ. 1. Одоогийн Буддын шашны сургаалын энгийн өгүүлбэрүүд нь ижил төстэй үгс, бүх номонд гарч буй догол мөр эсвэл шүлэгт байдаг. 2. Хичээлийн хоёр буюу түүнээс олон номнууд ижил төстэй үг олдсон. 3. Силас, Паранаа, аравдугаар сар, Патимокка. 4. Дилаа, Мажжима, Анутара, Самуата Никая нар. 5. Сатта Нипата, Тера, Тери Гатас, Уданас, Хаддака Пата нар. 6. Сатта Вибхана, мөн Хандарка. 7. Жатакас ба Дэммамбадууд. 8. Ниддеша, Йитттхакка ба Патисамббида нар. 9. Газрын зураг, Вимана-Ваттус, Ападана, Кэрия-Питака, Буддавама нар. 10. Абидраммын номууд; Хамгийн сүүлийн нь Ката-Ватту, хамгийн эртний нь Puggala-Pannatti юм. Жишээ

нь, нэгээс тав хүртэлх тооны дээд талд буюу дээд талд байрласан тэдгээр

хүмүүс бол хамгийн эртний, хамгийн эртний эх бичвэрүүд бөгөөд Буддын

жинхэнэ үгс, хамгийн үнэн үг байж магадгүй юм. Сүүлд

бичсэн текстүүд, тайлбарууд болон Вишүддхрэнга нь сонгодог Теравадагаас

маш их үнэлэгддэг бол орчин үеийн Теравада нь Буддагийн эртний сургаал

дээр төвлөрдөг.

Орчин үеийн Теравада Гол өгүүлэл: Орчин үеийн Теравада Бхавхи

Бххи, Дмамамдддхо Тха болон бусад шавь нар нь эргэлзээтэй байдаг. Орчин

үеийн эрдэмтдийн адил хожмын бичгүүдийн тухай, Буддавакана (Буддагийн

яг тодорхой үгс) гэх мэтээр эргэлздэг. Орчин үеийн Теравадинууд бага зэрэг янз бүрийн санал бодолтой байж магадгүй ч дараах зүйлсийн аль нэгийг нь авч болно: 1.

Эхний дөрвөн Никая нь бүхэлдээ Буддавакана бөгөөд Хаддака Назаяагийн

дараахь номуудыг багтаасан: Dhammapada, Udana, Itivuttaka, Sutta Nipata,

Theragatha, Therigatha; мөн Ватаяаас Патимокка. (Энэ нь Типитака-гийн буддавакana хэсгийг 40 ширхэгээс 30 орчим болгоно) 2.

Дээр дурдсан бүхэн, Khuddaka Nikaya-ийн бусад ном, бусад Vinai номууд,

дээр нь Абхидхамма гэхээс гадна Буддагийн дагалдагчдын бичсэнээр

тэдгээрийг харж болно. Canon-д багтдаг боловч Буддизмын анхных нь биш байж болох юм. Шинжлэх

ухааны эрдэмтэн Ахаха Судато, Ачах Брахмали нар Буддын эртний судруудын

бичсэн номыг бичсэн бөгөөд тэд эхний 4 Никая болон зарим Хаддака Никаяа

буддава гэж бичигдсэн байдаг. Эх сурвалж: Бурханы шашин

Лавлагаа Бурханы шашны номнуудын бүрэн жагсаалт - Тайлбарласан. Дэвид Н.Снайдер, Доктор, 2006.

http://www.thedhamma.com/

Бурханы шашны хэвлэн нийтлэлийн нийгэмлэг, Буддын ном хэвлэлийг 2014 онд баталсан.

https://suttacentral.net/

dhammawiki.com

Пали Канадын он дарааллын 1-10-р эрт эхээр - Dhamma Wiki

Буддын

Энэтхэгийн Томас Уильям Рис Дэвид (188-р хуудас) нь Бурхан багшийн үеэс

Ашока хот хүртэлх буддын ном судруудын он цагийн дарааллыг өгчээ.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=phjaV3pAcek

Filial piety of twenty-one Dari Ekh (bodhisattva) - (Mongolian Buddha Song)

Speed of Light

Published on Oct 27, 2015

Category

Music

Essays

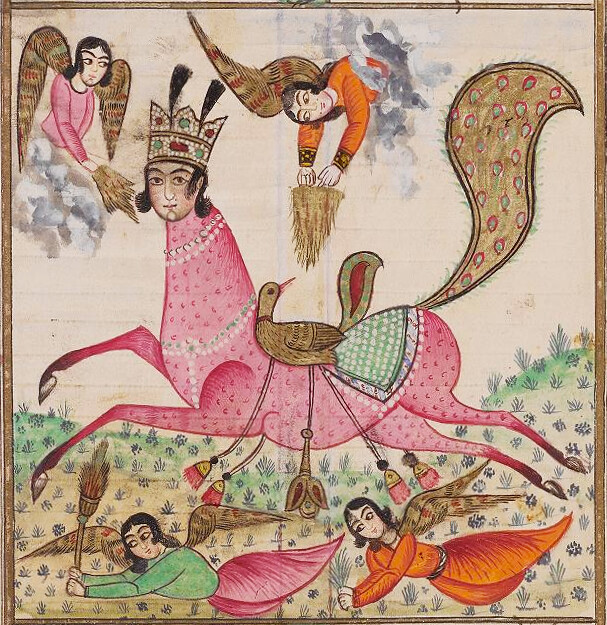

Out of Their Love They Made It: A Visual History of Buraq

Although mentioned only briefly in the Qur’an, the story of

the Prophet Muhammad’s night journey to heaven astride a winged horse

called Buraq has long caught the imagination of artists. Yasmine Seale

charts the many representations of this enigmatic steed, from early

Islamic scripture to contemporary Delhi, and explores what such a figure

can tell us about the nature of belief.

Oh this is the creature that never was.

They didn’t know it, still they dared

to love its stride, its bearing and its breast,

clean to the calm light of its eyes.

It was not. Out of their love they made it,

this pure creature . . .

Rainer Maria Rilke,

from Sonnets to Orpheus

You came here

because you were told to, and because here is where wonderful things are

known to happen at night. You comb the streets, the tangle of

unfamiliar smells — poultry, muskmelon, marigold — until you reach the

pockmarked, once-red wall of the Ship Palace. There’s a sad sort of

majesty to the place, but you’re not here for the beauty of ruins.

You’re here for the hauz, the tank, its fabled waters now

scummed over with algae and detritus. In your hand there is a pamphlet,

saffron yellow and Hindi scrawl, with a telephone number and an

instruction: to call between 6 and 8 p.m., to speak long and loud, to

say hello.

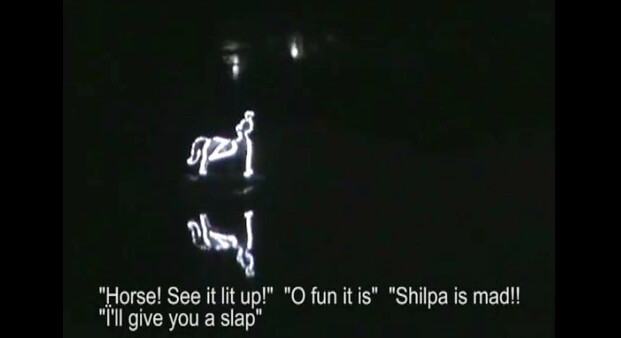

You say hello and for a moment the horse flickers into life, its

incandescent frame reflected in the water. A crowd has bloomed around

the tank. Children sing into receivers: “hello” becomes a ten-syllable

word. Soon the line is swamped as callers compete for the creature’s

fitful attention. Not quite the miracle you had in mind, this rickety

chimera — part neon piñata, part show pony, plus wings — assembled at

the local metalworks and lit up by Chinese-made LEDs. Still, it is a

thing of wonder: a winged horse rests on the surface of a lake and human

voices make it glow.

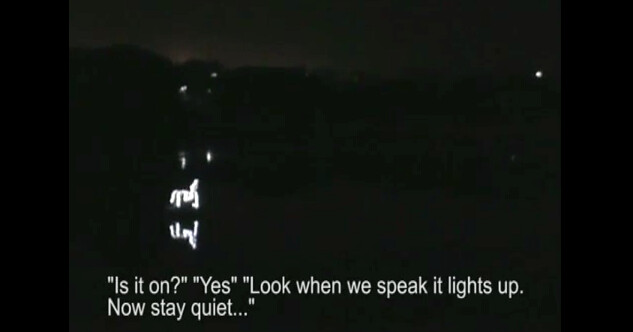

Say Hello to the Hauz

(2010), the brainchild of designer and filmmaker Vishal Rawlley, was an

attempt to revive the long-neglected water reservoir in Mehrauli, one

of the seven ancient cities that make up the state of Delhi. Drawing on

the story of the Prophet Muhammad’s ascent to heaven astride a winged

horse called Buraq, Rawlley designed a sculpture of the creature, fitted

it with a phone line and a constellation of fairy lights, and left it

to bob in the middle of the tank. People could dial in and speak; their

voices would trigger the phantasmagoria. In the night footage preserved

online, Buraq’s skeleton flashes on and off to the babble of unseen

voices. The gasps are subtitled, the curiosity palpable. What to an

outsider may have seemed an alien landing was really the portal to a

mythic past: the horse had a history here.

The hauz was built in the thirteenth century after an early

“slave sultan” of Delhi, Shamsuddin Iltutmish, dreamed he was visited by

the Prophet Muhammad astride his winged steed. In the dream, the

Prophet directed the king to a fountainhead that sprang where Buraq

struck the ground with her hoof. On waking, the story goes, Iltutmish

hurried to the site where he discovered the mark of a hoof imprinted on

the earth. Dreams were an important part of the apparatus of medieval

kingship; auspicious visions could steady a shaky crown. More, a widely

circulated hadith declared that seeing the Prophet in a dream was equal

to seeing him physically. To dream of the Prophet, then — in other

words, to be considered a direct witness to his words and deeds, which

together form the basis of Islamic law — was to be in a very privileged

position indeed, and Iltutmish acknowledged the honour with due piety:

he built a water tank, the Hauz-i-Shamsi, to mark the hallowed spot. For

centuries the tank remained a site of local devotion. Magical

properties were ascribed to its waters, and the great fourteenth-century

traveller Ibn Battuta described how small boats ferried pilgrims to the

red sandstone pavilion at its centre.

The story of the reservoir and its otherworldly aura echoes another

origin myth: that of the Hippocrene, or Horse Fountain, which sprang

from the hoof-scuff of Pegasus and is remembered in Greek mythology as a

fount of poetic inspiration. Unlike Pegasus, however, who emerged fully

formed from the blood of Medusa, Buraq’s conception was gradual, her

evolution more peculiar and circuitous. She crops up on Persian

miniatures and Pakistani trucks, Zanzibari ephemera and Libyan

airplanes, Senegalese glass paintings and Indian matchboxes. Yet despite

her many incarnations, or perhaps because of them, her essence remains

elusive. There is no original, no definitive Buraq, but rather an unruly

palimpsest of jumbled creeds, kitsch, and sheer artistic caprice.

The bare bones of Buraq look like this. From the Arabic root b-r-q,

which means to shine or sparkle, her name evokes the lightning speed

with which she carried the Prophet from Mecca to Jerusalem and thereon

to heaven, an episode known as the mi‘raj, or “ascension”. The

Qur’an alludes to this journey — in two cryptic verses that lend a whole

chapter (“The Night Journey”) its title — but makes no mention of the

vehicle. Because Buraq is absent from scripture, theologians give her

short shrift, confining her to fly-by-night cameo roles: she first

appears in the eighth century, in the earliest extant biography of the

Prophet, as a “winged beast, white in colour, smaller than a mule and

larger than an ass”. Buraq is a creature not of scripture but of lore,

and in these early writings she is still a vague, unfinished thing,

uncertain of shape, let alone sex. She will take centuries to evolve a

human face: some five hundred years passed before the historian

al-Tha‘labi wrote that Buraq “had a cheek like the cheek of a human

being”, a not-quite metaphor that launched her never quite completed

metamorphosis.

— Source.

The literature on Muhammad’s ascension to heaven grew to be enormous,

but only after it slipped its scriptural moorings and slid out into

poetry and folklore. Every life of the Prophet had a chapter on the

subject, and scholars and mystics endlessly pondered its meaning. The

story was deployed and reinterpreted among Islam’s subcultures, and also

among its foes: there are versions in Malay, Uzbek, and Old French, in

Buginese and Castilian, and a beautifully illuminated version in

Chaghatay, a form of Middle Turkish named after Genghis Khan’s second

son. Like Buraq herself, the story has never settled into a final form;

it alters every time it is told. In some accounts, the duo do not stop

at Jerusalem but venture through the seven heavens where, at the climax

of their journey, the Prophet comes face to face with God. There he

might meet a celestial rooster, or a polycephalous angel, and sometimes

he pays a visit to his mother and father in hell. In others, the Prophet

ascends to heaven by means of a glittering ladder, having fastened

Buraq to a wall at the foot of the Temple Mount. (To this day the spot

is known as the Buraq Wall to Muslims and the Western or Wailing Wall to

Jews.)

Buraq was not born a woman, she became one — but when this happened

is unclear. At some point an anonymous genius gave her a lustrous mane

and a jeweled throat, and artists have never looked back. In her many

guises classical and modern, Buraq is squarely female, adorned now with a

peacock tail, now with a leopard-print coat, almost always with a

gem-encrusted crown and brightly coloured wings. She grew into a staple

of Muslim visual art, seizing the collective imagination until writers

too followed suit. By the sixteenth century, the Persian historian

Khwandamir could write that Buraq had

a face like that of a human and ears like those of an

elephant; its mane was like the mane of a horse; its neck and tail like

those of a camel; its breast like the breast of a mule; its feet like

the feet of an ox. Its breast looked just like a ruby and its hair

resembled white armor, shining brightly by reason of its exceeding

purity.

The Persian language has no gender, obliging writers like Khwandamir

to continue to describe Buraq in neuter terms even as she gained in

feminine lustre and finery. It is perhaps no coincidence that Buraq is

most spectacularly beautified in works by Persian miniaturists, as if

these artists were giving excessively lavish expression to a femininity

their language would not allow them to convey in words — as if the

sexual restraint (the “greyness”) imposed by one medium made for an

aesthetic of sexual maximalism in another.

from present-day Uzbekistan and Afghanistan, probably Bukhara and Herat — Source.

If Buraq’s early, skeletal form most recalled Pegasus, the sexless

winged horse of classical antiquity, her new embellishments brought her

closer to those other feminized hybrids, Sphinx and Chimera. Gustave

Flaubert summed up the appeal of such composite, yet distinctly female

creatures: “Who has not found the Chimera charming; who has not loved

her lion’s snout, her rustling eagle’s wings, and her green-glinting

rump?” In taking on the allure of these figures, however, Buraq also

acquired a troubling ambiguity. After all, unlike those other mythical

beings, Buraq is a devotional object, theologically more akin to an

archangel than to a many-headed beast of prey. She is, existentially,

inseparable from Muhammad — she exists only to carry him on his journey —

making her feminized appearance all the more startling. Visually, they

evolve in opposite directions: the more Buraq gains in baroque

adornment, the more the figure of Muhammad seems to retreat into

allegory. As her body comes to the fore, his grows austere and

immaterial.

Bodies are everywhere in this story, and they are awkward. The

friction between the historical Prophet and his fantastical mount,

between the sacred and the physical, reflects a similar divide within

Buraq herself: she has been perceived both as a dream-horse — mythical,

sexless, emblematic — and as a creature of flesh. And Buraq as animal,

especially in her more sexualised incarnations, in turn raises thorny

questions about the body of the Prophet himself. Artists generally

elided this problem, or creatively eluded it; early images of the

Prophet tend to show him with a veil, and more recently his body has

been symbolized by a white cloud, a rose or a flame.

of Buraq, with the Prophet Muhammad represented by stylised flames,

from an 18th-century Ottoman manuscript, AD 1717 — Source.

Did the Prophet ascend to heaven in body or only in spirit? For all

those who grappled with the meaning of the night journey, this was a

central question. One solution was to skirt the problem of bodies

altogether. The Persian polymath Avicenna thought the mi‘raj a

purely internal, intellectual journey; less concerned with Muhammad’s

ascent than with the potential elevation of anyone engaged in abstract

thought, he used the story’s currency as a folk narrative to coax a

largely uninitiated community into the pursuit of philosophy. For

Avicenna, the ascension tale was a useful means of dispelling anxieties

about foreign intellectual traditions: by presenting these questions in

terms familiar to his Muslim audience — and by reframing the Prophet’s

ascension as a spiritual journey one should try to emulate — he showed

that the study of philosophy was not only compatible with traditional

Islamic teachings, but central to the task of the pious believer.

This sounds all very well and rational, but if bodies are erased from

the story — if the night journey was merely a voyage of the mind, a

static reverie — what is to be done with Buraq, who is pure colour and

pure form, who stands for nothing beyond her exuberant self? Avicenna

doesn’t say. The reality of the prophet’s flight is dismissed in a line

(“It is known that he did not go in the body, because the body cannot

traverse a long distance in one moment”), but winged horses are not so

easily idealised. Buraq is unavoidably, infectiously physical. Astride

her back, the Prophet is wrenched out of abstraction, trapped and

tangled up in the body of the beast as Leda by the swan in Yeats’ poem:

“and how can body, laid in that white rush / But feel the strange heart

beating where it lies?”

Others felt it too. The Ottoman poet Veysi was obsessed with the

physical character of the night journey, which he held to be the salient

event in Muhammad’s biography; his contribution to the genre was

accordingly titled The Life of the One Who Ascended. Veysi’s most famous work, the Habname

or Book of Dreams, takes the form of a dream conversation between

Sultan Ahmed I and Alexander the Great, and suggests a belief in the

essential fluidity between the world of dreams and real life. A similar

fluidity pervades Veysi’s account of the night journey, which stresses

the physical reality of the ascension and of the transcendental world to

which the Prophet traveled. Central to his argument are detailed

descriptions of Buraq and of the Lote Tree of the Limit, which marks the

edge of heaven and the boundary beyond which nothing can pass. The tree

has an infinite number of branches, each with an infinite number of

leaves, and on each leaf sits a huge angel carrying a staff of light. A

Sufi text calls it “a tree without description”, which grew from “an

unimaginable ocean of musk”. What sorts of things are these that are

rendered in exquisite detail yet remain “without description”, both

sensually evoked and still “unimaginable”? The clue to Buraq’s nature,

perhaps, lies in this paradox.

That Avicenna and Veysi represent seemingly irreconcilable views —

that Buraq can be considered both pure abstraction and pure physicality —

is hardly surprising; it is in her nature to divide. In its earliest

versions the ascension story functioned as a kind of shibboleth: those

who believed in Muhammad’s heavenly ascension were regarded as having

accepted his prophetic mission, whereas those who did not were deemed to

have rejected Islam itself. This problem of belief was recently revived

in a debate archived on YouTube under the title “Richard Dawkins versus

Muhammad’s Buraq horse”. The Oxford Union had invited Dawkins, the

evolutionary biologist, to share the stage with the journalist Mehdi

Hasan — Science v. Religion, firebrand against firebrand. At one point

in the video, Dawkins exclaims twice in disbelief: “You believe Muhammad

flew to heaven on a winged horse!” The crowd jeers, Hasan flounders,

and the debate grinds to a deadlock. The mere mention of Buraq — her

quaintness, her garish absurdity — was apparently enough to clinch the

argument, exposing Hasan the “believer” as irretrievably backward,

painfully naive, or a fraud.

The debate made for uncomfortable viewing. It seemed odd that among

all the mystery of religious lore, the night journey — and its

sensational metonym, the winged horse — should be singled out for

special treatment in this way. Buraq, true to her name, seems to have

become a lightning rod in the atheist crusade, a byword for the

irrationality of Islam and religion in general. Yet by posing the

question restrictively in terms of “belief”, both speakers ignored the

many ways in which believers and non-believers might engage with an

object like Buraq (in the literal sense of object, “a thing presented to

the mind”), not simply as an article of faith but as metaphor, myth,

paradox, emblem, or visual trope.

Buraq is a product of miscegenation. First found in the nineteenth

century BC, the motif of winged horses was picked up by the Assyrians,

made its way through Greece and Asia Minor, and eventually became

ubiquitous in Eurasia: Etruscans, Persians, Celts, Finns, Koreans,

Bengalis, and Tatars all boast some version of the myth. Often these

horses are able to travel at supernatural speed; they sometimes have a

human head; and they can also be linked to storms and lightning. So it

turns out that Buraq, far from being the risible cultural aberration

deplored by Dawkins, is actually a version of one of the oldest and most

widespread myths in our history, her shimmering body a receptacle for

the many myths, metaphors, and moral concerns that Islam inherited.

The world was a combination of real and mythological objects until

somewhat recently; a clear distinction could hardly be made before the

onset of modern comparative biology. And yet science has not abolished

the interstitial zone which a figure like Buraq inhabits: we need such

liminal objects to connect seemingly divergent realms of empirical and

spiritual experience. Her presence in contemporary culture acts as a

bridge between knowledge and belief, between rationalist taxonomies of

the world and the vestigial power of myth. This idea finds its most

forceful and literal expression in the Islamic transport industry, where

the figure of Buraq, usefully combining piety and speed, recurs as a

kind of patron saint. She gives her name to airlines from Libya to

Indonesia, to bus companies, freight ships and motorcycle-taxis, to a

space camp, to an engineering college, and to Pakistan’s first drone.

The fluidity of Buraq as an aesthetic and linguistic object perhaps

explain her pliability in being put to commercial use: she presides not

just over wings and wheels but is also used to sell plastic and PVC,

heavy metal and heavy-duty diesel (BURAQ LUBRICANTS), Indian food, and

surgical instruments.

The longer you study her, the deeper you dig, the more elusive

Buraq’s identity becomes. In a luminous essay, “The Chimera Herself”,

Ginevra Bompiani parses the symbolic implications of these composite

creatures. The many-headed Chimera exemplifies the arbitrary union of

countless experiences — she is the synthesis of disparate things. “She

who, in myths, was purely a fiery apparition, without a voice or a

history, was to become, in the early days of modern philosophy, the ens rationis,

the creature of language, the metaphor of metaphor”. As a hybrid, Buraq

does what metaphors do: she makes the impossible visible. “Achilles is a

lion” is literally false; you cannot figure it, yet there it is on the

page. In the basic metaphorical statement, “A is B”, Buraq plays the

same role as the copula (the “is”), brazenly flouting the law of

non-contradiction, mixing that which should not be mixed. “Since she

does not exist”, Bompiani writes, “the question arises as to what

Chimera is“. That depends, some might say, on what the meaning of the word is is.

Yasmine Seale is a writer and translator. She is reading for a PhD on Ottoman attitudes to antiquity at St John’s College, Oxford.

69) Classical Myanmar (Burmese)

69), Classical မြန်မာ (ဗမာ)

2650 Wed 13 Jun ကသင်ခန်းစာ

ယခု

105

Classic ဘာသာစကားများအတွက် http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org

မှတဆင့်အခမဲ့အွန်လိုင်းTipiṭakaသုတေသနနှင့်လေ့ကျင့်တက္ကသိုလ်နှင့်ဆက်စပ်သတင်းများ

- analytic ဝိပဿနာ Net က

Paṭisambhidāဂျာ-Abaddha

Paripanti TipiṭakaAnvesanā ca ကို Paricaya Nikhilavijjālaya CA

ñātibhūta Pavatti Nissāya http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org anto 105

SeṭṭhaganthāyattaBhāsā

တစ်ဦး Online News CHANNEL ဖြစ်ပါသည်

ကျော်ကို 3000 အီးမေးလ်များဖို့သူ့မှာအရမ်းကောင်းတဲ့:

200 WhatsApp ကို, Facebook နှင့် Twitter ။

https://dhammawiki.com/index.php/1-10_early_to_recent_Chronology_of_Pali_Canon

https://dhammawiki.com/…/1-10_early_to_recent_Chronology_of…

အစောပိုင်းပါဠိကို Canon ၏မကြာသေးခင်ကမှတ်တမ်းမှ 1-10

မိမိအဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာအိန္ဒိယနိုင်ငံတွင်သောမတ်စ်ဝီလျံ

Rhys Davids (။ p 188) မှာအောက်ပါအတိုင်းဖြစ်သည့် Ashoka

၏အချိန်မှဗုဒ္ဓ၏အချိန်ကနေဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာစာပေ၏အချိန်နဲ့တပြေးညီစားပွဲပေါ်မှာအားပေးတော်မူပြီ:

1.

ဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာအယူဝါဒ၏ရိုးရှင်းထုတ်ပြန်ချက်များယခုတူညီစကား,

အပိုဒ်တွင်သို့မဟုတ်အပေါငျးတို့သစာအုပ်တွေထဲမှာထပ်တလဲလဲကျမ်းပိုဒ်,

တွေ့ရှိခဲ့ပါတယ်။

2. ဇာတ်လမ်းတွဲများလက်ရှိစာအုပ်နှစ်ခုသို့မဟုတ်နှစ်ခုထက်ပိုသောအတွက်တူညီစကား, တွေ့ရှိခဲ့ပါတယ်။

3. သိလတို့သည် Parayana, အ Octades, အ Patimokkha ။

4. Digha, Majjhima, Anguttara နှင့် Samyutta Nikayas ။

5. အဆိုပါသုတ် Nipata, ထိုမထေရ်နှင့် Theri Gathas, အ Udanas, နှင့် Khuddaka-Patha ။

6. သုတ် Vibhanga နှင့် Khandhkas ။

7. အဆိုပါ Jatakas နှင့်တရား။

8. အဆိုပါ Niddesa, အ Itivuttakas နှင့် Patisambbhida ။

9 PETA နှင့် Vimana-Vatthus, အ Apadana, အ Cariya-Pitaka, နှင့် Buddhavamsa ။

10. ထိုအဘိဓမ္မာစာအုပ်တွေ; အရာ၏နောက်ဆုံးယင်းကတ်-Vatthu နှင့်အစောဆုံးဖြစ်နိုင် Puggala-Pannatti ဖြစ်ပါတယ်။

ထိုကဲ့သို့သောမှငါးဂဏန်းတစ်ဦးအဖြစ်ထိပ်မှာသို့မဟုတ်ထိပ်အနီးစာရင်းဝင်သောသူတို့ကို,

အစောဆုံး,

အသက်အကြီးဆုံးစာသားများနှင့်စစ်မှန်ဖြစ်အရှိဆုံးဖွယ်ရှိနှင့်ဗုဒ္ဓ၏အအတိအကျစကားလုံးများကိုထည့်သွင်းစဉ်းစားနေကြသည်။

ခေတ်သစ်ထေရဝါဒဗုဒ္ဓ၏အစောဆုံးသွန်သင်ချက်အပေါ်အလေးပေး,

သော်လည်းနောက်ပိုင်းစာသားများနှင့်မှတ်ချက်အများနှင့် Visuddhimagga,

Classical ထေရဝါဒနေဖြင့်အလွန်မြင့်မားတန်ဖိုးထားအတွက်ကျင်းပကြသည်။

ခေတ်သစ်ထေရဝါဒ

ပင်မဆောင်းပါး: ခေတ်သစ်ထေရဝါဒ

နောက်ပိုင်းစာသားများနှင့်

ပတ်သက်. သူတို့ Buddhavacana (ဗုဒ္ဓအတိအကျစကားလုံးများကို)

သို့မဟုတ်မဟုတ်ကြလျှင်ခေတ်သစ်ပညာရှင်များပြောသကဲ့သို့ရဟန်းသည်ဗောဓိ,

Dhammavuddho မထေရ်နှင့်အခြားသူများ, သူတို့ရဲ့သံသယရှိသည်။ ခေတ်သစ် Theravadins ဖြစ်ကောင်းထင်မြင်ယူဆ၏အနည်းငယ်အမျိုးမျိုးကိုင်ထားပေမယ့်ဖြစ်ကောင်းအောက်ပါများထဲမှယူ:

1.

သူတို့ရဲ့တခုလုံးကိုပထမဦးဆုံးအလေး Nikayas Buddhavacana ဖြစ်ကြသည်ပေါင်း

Khuddaka Nikaya မှအောက်ပါစာအုပ်များကို: တရား, Udana, Itivuttaka, သုတ်

Nipata, Theragatha နှင့် Therigatha; နှင့်ဝိနည်းထံမှ Patimokkha ။ (ဒါကဆဲ Tipitaka ၏ Buddhavacana သောအဘို့ကိုအကြမ်းအားဖြင့် 30 ကျော် 40 volumes ကိုထဲကလုပ်လိမ့်မယ်။ )

2.

အထက်ပါအားလုံး, ပေါင်း Khuddaka Nikaya ၏အခြားစာအုပ်များ,

ပေါင်းသည်အခြားဝိနည်းစာအုပ်များ,

ပေါင်းအဘိဓမ္မာပေမယ့်ဗုဒ္ဓအကြာတွင်တပည့်ကရေးသားအဖြစ်သူတို့ကိုမြင်,

ရဟန္တာဖြစ်နှင့်ဖြစ်ဤသို့ဆဲခံထိုက်ကြပေမည်သူကို မူရင်းဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာမဟုတ်ဖွယ်ရှိအစိတ်အပိုင်းတစ်ခုဖြစ်သော်လည်းကို Canon အတွက်ပါဝင်သည်။

အဆိုပါပညာရှင်

Ajahn Sujato နှင့် Ajahn Brahmali စာအုပ်အစောပိုင်းဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာစာသားရဲ့

Authenticity

ရေးထားပြီသူတို့အထက်အရေအတွက်ကတဦးတည်းနှင့်အတူသဘောတူညီချက်၌ရှိကြ၏,

ပထမဦးဆုံး 4 Nikayas နှင့် Buddhavacana အဖြစ် Khuddaka Nikaya

အချို့ပါဝင်သည်ဟုရဟန်းသံဃာ။

ကိုလည်းကြည့်ပါ: မူရင်းဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာ

ကိုးကား

ဗုဒ္ဓရဲ့စာရင်း၏အပြီးအစီးစာအုပ် - ရှင်းလင်းချက်။ ဒါဝိဒ်သည် N. Snyder, Ph.D ဘွဲ့ကို, 2006 ။

http://www.thedhamma.com/

အစောပိုင်းဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာကျမ်းစာသို့ဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာပြည်သူများလူ့အဖွဲ့အစည်းရဲ့စစ်မှန်မှုကို, 2014 ။

https://suttacentral.net/

dhammawiki.com

ဓမ္မဝီကီ - အစောပိုင်းပါဠိကို Canon ၏မကြာသေးခင်ကမှတ်တမ်းမှ 1-10

မိမိအဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာအိန္ဒိယနိုင်ငံတွင်သောမတ်စ်ဝီလျံ

Rhys Davids (။ p 188) မှာအောက်ပါအတိုင်းဖြစ်သည့် Ashoka

၏အချိန်မှဗုဒ္ဓ၏အချိန်ကနေဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာစာပေ၏အချိန်နဲ့တပြေးညီစားပွဲပေါ်မှာအားပေးတော်မူပြီ:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N8uRJWMaPnk

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N8uRJWMaPnk

Pathana Pali Chant ပ႒ာန္းပါဠိေတာ္

ဖိုး ေဂၚရခါး

Published on Mar 20, 2012

Payategyi,Pathan pali chant and Metta Bhawana,Buddha Ane kazar in Myanmar by Mahar Kan Pat

Lae Sayadaw U Nanda Mitzutar

Category

Nonprofits & Activism

https://www.pariyatti.org/P%C4%81li

Pāli

Twenty-five centuries ago Pāli was the main language spoken in

northern India, the dialect in which the Buddha taught, and the language

the teachings are written in the Tipiṭaka. Pariyatti’s aim is to

provide greater access to the words of the Buddha, which will enable a

deeper understanding of the Buddha’s teaching, the Dhamma. Find

residential workshops, an online learning center, the Tipiṭaka, Pāli

books, and Pāli Word a Day email service to help strengthen your

understanding of Pāli.

Your browser does not support inline frames

____________________________________________

Your browser does not support inline frames

____________________________________________

An RSS feed of Pāli Word a Day, to use with a news aggregator,

is available using this link:

![]() Pāli Word a Day RSS.

Pāli Word a Day RSS.

More feeds are available on the

RSS feeds page.

____________________________________________

Click AppStore or Google play to download Pāli Word a Day app

bundled with Daily Words of the Buddha app.

The teachings of the Buddha are preserved in the Pāli Canon, an

extensive, detailed, systematic and analytical record. Twenty-five

centuries ago Pāli was the lingua franca of northern India, the

dialect in which the Buddha taught. Just as Sanskrit is the canonical

language of Hinduism and Latin the canonical language of Catholicism,

Pāli is the classical language in which the teachings of the Buddha have

been preserved. The Pāli sources are the Tipiṭaka (the Pali Canon); the

sub-commentaries, called the Aṭṭhakathā, Tikā and others such as Anu-tikā, Madhu-tikā, etc.

Pāli Canon

The Pāli sources are the Tipiṭaka (the Pali Canon); the

sub-commentaries, called the Aṭṭhakathā, Tikā and others such as

Anu-tikā, Madhu-tikā, etc.

70) Classical Nepali

70) शास्त्रीय नेपाली 2650 बुध 13 जुन पाठ अहिले विश्लेषणात्मकइन्साइट नेट - नि: शुल्क अनलाइन टिपीटाक रिसर्च एण्ड प्रविधि

विश्वविद्यालय र 105 क्लासिकल भाषाहरूमा http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org

मार्फत सम्बन्धित समाचार Paṭisambhidā

Jāla-Abaddha Paripanti Tipiṭaka Anvesanā ca Paricaya Nikhilavijjālaya

ca ñātibhūta Pavatti Nissāya http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org anto 105

Seṭṭhaganthāyatta Bhāsa एक अनलाइन समाचार च्यानल हो

3000 देखि अधिक इमेल को लागि खानपान:

200 व्हाट्सएप, फेसबुक र ट्विटर। https://dhammawiki.com/index.php/1-10_early_to_recent_Chronology_of_Pali_Canon https://dhammawiki.com/…/1-10_early_to_recent_Chronology_of…

1-10 पहिले पाली क्यानन को क्रान्तिको शुरुवात उनको

बौद्ध भारत (पृष्ठ 188) मा थमस विलियम राइज डेविडले बुद्ध साहित्यको बौद्ध

साहित्यको तालिकालाई बुद्धको समयमा अशोकको रूपमा दिएका छन्: 1. बौद्ध शिक्षा को सरल बयान अब, सबै शब्दहरु मा पुनरावृत्ति अनुच्छेद या पदहरुमा समान शब्दहरु मा पाइन्छ। 2. एपिसोडहरू भेटिए, समान शब्दहरूमा, अवस्थित पुस्तकहरूको दुई वा बढीमा। 3. सिलास, पराना, अक्टोड्स, पटिमोकखा। 4. दघा, मझ्हामा, अंगुरा, र सम्योटा नाकाया। 5. सता निपता, थरा र थरी गठना, उदय, र खुड्का पथ। 6. सुता विभभाङ, र खांधका। 7. जटाकस र ढम्मापाडा। 8. निडिसा, इटवाट्टास र पितिसबबहिडा। 9। पिटा र भिमा-वाटथस, अपडेना, कार्या-पिटाका, र बौद्धामा। 10. अभिषेक पुस्तकहरू; जसको अन्तिम भाग कथ-वाटौू हो, र सबैभन्दा पहिले सम्भवतः पगगला-प्याननाटी। माथिल्लो

सूचीमा माथि वा माथिको माथिल्लो सूची, जस्तै अंकहरू एक देखि पाँच, ती सबै

भन्दा पुरानो, पुरानो ग्रंथहरू र ती सबै प्रमाणहरू र बुद्धका सही शब्दहरू

मानिन्छ। पछिका

ग्रंथहरू र टिप्पणीहरू र भद्देश्यगागाहरू शास्त्रीय थेरेराडाले धेरै उच्च

सम्मानमा राख्छन्, जबकि आधुनिक थेरैडाडा बुद्धका सबैभन्दा प्रारम्भिक

शिक्षाहरूमा ध्यान दिन्छन्।

आधुनिक थेरेवाडा मुख्य लेख: आधुनिक थेरेवडा Bhikkhu

Bodhi, धम्मवौधो थरा र अरूसँग उनीहरूको संदेह छ, पछिका ग्रंथहरू जस्तै

पछिल्ला ग्रन्थहरू र यदि तिनीहरू बौद्धाण्य हुन् (बुद्धको सही शब्द) वा

होइन। आधुनिक थियेडेनियन्सले विभिन्न प्रकारको प्रतिक्रियाहरू राखेका छन् तर शायद निम्न मध्ये एक लिन्छन्: 1.

पहिलो सम्पूर्ण नेकाहरू बौद्धका हुन्, साथै खाडाका निकयाका निम्न

पुस्तकहरू: ढम्मपाडा, उडाना, इटिभटक, सुत्ता निपाता, थेरेगाथा र थरिगुता; र विनाया देखि पतमोकखा। (त्यो अझै पनि Tipitaka को बौवाकाना भाग लगभग 40 मात्रा मध्ये लगभग 30 हुनेछ।) 2.

माथिको सबै, प्लस खड्का निक्याका अन्य पुस्तकहरू, साथै अन्य विनाया

पुस्तकहरू, साथै अभहिम्मा, तर उनीहरूलाई बुद्धका पछिल्ला चेलाहरू द्वारा

लिखित रूपमा हेर्नुहोस्, जसले आह्वान गरेका थिए र यसरी, अझै पनि योग्य हुन

सक्दछ। कैननमा समावेश, यद्यपि सम्भावना नभएको बौद्ध धर्मको अंश। विद्वान

भिक्षु अजहान सुजुतो र अजह ब्रह्मलीले प्रारम्भिक बौद्ध ग्रंथहरूको

प्रमाण पत्र लेखेका छन् र उनीहरूको संख्या एक माथिको सम्झौतामा रहेको छ,

पहिलो 4 नेक्य र केहि खाडाका नलिकालाई बौद्धाणा भनिन्छ। यो पनि हेर्नुहोस: मूल बौद्धता

सन्दर्भहरू बुद्धको सूचीहरूको पूर्ण पुस्तक - व्याख्या गरिएको। डेभीड एन। सिनेडर, पीएच.डी., 2006।

http://www.thedhamma.com/

प्रारम्भिक बौद्ध ग्रन्थहरूको बौद्धिकता बौद्ध प्रकाशन समाज, 2014।

https://suttacentral.net/

dhammawiki.com

1-10 को शुरुवात सम्म पली कैनन - धम्मा विकी को क्रान्ति

उनको

बौद्ध भारत (पृष्ठ 188) मा थमस विलियम राइज डेविडले बुद्ध साहित्यको बौद्ध

साहित्यको तालिकालाई बुद्धको समयमा अशोकको रूपमा दिएका छन्:

https://www.youtube.com/watch…

Jahan Chan Buddha Ka Ankhan (Nepali)

Ricky Shrestha

Published on Dec 6, 2007

Another favorite song..

Category

Entertainment

Insight Net - GRATIS Online Tipiṭaka Research and Practice University

og relaterte NYHETER gjennom http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org i 105

KLASSISKE SPRÅK Paṭisambhidā

Jāla-Abaddha Paripanti Tipiṭaka Anvesanā ca Parikaya Nikhilavijjālaya

ca ñātibhūta Pavatti Nissāya http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org anto 105

Seṭṭhaganthāyatta Bhāsā er en online nyhetskanal

Catering til mer enn 3000 e-poster:

200 WhatsApp, Facebook og Twitter. https://dhammawiki.com/index.php/1-10_early_to_recent_Chronology_of_Pali_Canon https://dhammawiki.com/…/1-10_early_to_recent_Chronology_of…

1-10 tidlig til siste kronologi av Pali Canon Thomas

William Rhys Davids i sitt buddhistiske India (s. 188) har gitt et

kronologisk bord av buddhistisk litteratur fra Buddha-tiden til Ashoka

som er som følger: 1. De enkle utsagnene om buddhistisk doktrin fant nå, i identiske ord, i avsnitt eller vers som er tilbake i alle bøkene. 2. Episoder funnet i identiske ord i to eller flere av de eksisterende bøkene. 3. Silas, Parayana, Octadene, Patimokkha. 4. Digha, Majjhima, Anguttara og Samyutta Nikayas. 5. Sutta Nipata, Thera og Theri Gathas, Udanas og Khuddaka Patha. 6. Sutta Vibhanga og Khandhkas. 7. Jatakas og Dhammapadas. 8. Niddesa, Itivuttakas og Patisambbhida. 9. Peta og Vimana-Vatthus, Apadana, Cariya-Pitaka og Buddhavamsa. 10. Abhidhamma bøkene; Den siste er Katha-Vatthu, og den tidligste sannsynligvis Puggala-Pannatti. De

som er oppført øverst eller nær toppen, for eksempel tallene 1-5,

regnes som de tidligste, eldste teksten og mest sannsynlig å være

autentiske og Buddhas eksakte ord. De

senere tekster og kommentarene og Visuddhimagga holdes i stor grad av

klassisk Theravada, mens den moderne Theravada fokuserer på Buddhas

tidligste lære.

Moderne Theravada Hovedartikkel: Modern Theravada Bhikkhu

Bodhi, Dhammavuddho Thera og andre har sine tvil, som moderne lærde om

senere tekster, og om de er Buddhavacana (eksakte Buddha-ord) eller

ikke. Moderne Theravadins inneholder sannsynligvis et lite utvalg meninger, men sannsynligvis ta ett av følgende: 1.

De første fire Nikayaene i sin helhet er Buddhavacana, pluss følgende

bøker fra Khuddaka Nikaya: Dhammapada, Udana, Itivuttaka, Sutta Nipata,

Theragatha og Therigatha; og Patimokkha fra Vinaya. (Det vil fortsatt gjøre Buddhavacana-delen av Tipitaka omtrent 30 av 40 volumer.) 2.

Alt ovenfor, pluss de andre bøkene til Khuddaka Nikaya, pluss de andre

Vinaya-bøkene, pluss Abhidhamma, men se dem som skrevet av senere

Buddhas disipler, som kanskje har vært arahanter og dermed fortsatt

verdige til å være inkludert i kanon, men ikke sannsynlig del av opprinnelig buddhisme. De

lærde munkene Ajahn Sujato og Ajahn Brahmali har skrevet boken

Authenticity of Early Buddhist Texts, og de er enige med nummer ett

over, bestående av de første 4 Nikayasene og noen av Khuddaka Nikaya som

Buddhavacana. Se også: Original Buddhism

referanser Den komplette boken av Buddhas lister - forklart. David N. Snyder, Ph.D., 2006.

http://www.thedhamma.com/

Autentisiteten til buddhistiske publikasjonssamfunnet for tidlig buddhistiske tekster, 2014.

https://suttacentral.net/

dhammawiki.com

1-10 tidlig til siste kronologi av Pali Canon - Dhamma Wiki

Thomas

William Rhys Davids i sitt buddhistiske India (s. 188) har gitt et

kronologisk bord av buddhistisk litteratur fra Buddha-tiden til Ashoka

som er som følger:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P4HnqxXKJvM

Pchum Ben Ceremony, Khmer Buddhist Center, NORWAY, 16-9-2017

Nokor K.

Published on Sep 29, 2017

Pchum Ben Ceremony, Khmer Buddhist Center, NORWAY, 16-9-2017

Category

News & Politics

https://dhammawiki.com/…/1-10_

1-10 early to recent Chronology of Pali Canon

Thomas William Rhys Davids in his Buddhist India (p. 188) has given a

chronological table of Buddhist literature from the time of the Buddha

to the time of Ashoka which is as follows:

1. The simple statements of Buddhist doctrine now found, in identical

words, in paragraphs or verses recurring in all the books.

2. Episodes found, in identical words, in two or more of the existing books.

3. The Silas, the Parayana, the Octades, the Patimokkha.

4. The Digha, Majjhima, Anguttara, and Samyutta Nikayas.

5. The Sutta Nipata, the Thera and Theri Gathas, the Udanas, and the Khuddaka Patha.

6. The Sutta Vibhanga, and Khandhkas.

7. The Jatakas and the Dhammapadas.

8. The Niddesa, the Itivuttakas and the Patisambbhida.

9. The Peta and Vimana-Vatthus, the Apadana, the Cariya-Pitaka, and the Buddhavamsa.

10. The Abhidhamma books; the last of which is the Katha-Vatthu, and the earliest probably the Puggala-Pannatti.

Those listed at the top or near the top, such as numbers one to five,

are considered the earliest, oldest texts and the most likely to be

authentic and the exact words of the Buddha. The later texts and the

commentaries and the Visuddhimagga, are held in very high esteem by

Classical Theravada, whereas, the Modern Theravada focuses on the

earliest teachings of the Buddha.

Modern Theravada

Main article: Modern Theravada

Bhikkhu Bodhi, Dhammavuddho Thera and others have their doubts, as do

modern scholars about the later texts and if they are Buddhavacana

(exact words of Buddha) or not. Modern Theravadins probably hold a

slight variety of opinions but probably take one of the following:

1. The first four Nikayas in their entirety are Buddhavacana, plus the

following books from the Khuddaka Nikaya: Dhammapada, Udana, Itivuttaka,

Sutta Nipata, Theragatha, and Therigatha; and the Patimokkha from the

Vinaya. (That would still make the Buddhavacana portion of the Tipitaka

roughly 30 out of 40 volumes.)

2. All of the above, plus the

other books of the Khuddaka Nikaya, plus the other Vinaya books, plus

the Abhidhamma, but see them as written by later disciples of the

Buddha, who may have been arahants and thus, still worthy to be included

in the Canon, although not likely part of Original Buddhism.

The

scholar monks Ajahn Sujato and Ajahn Brahmali have written the book The

Authenticity of Early Buddhist Texts and they are in agreement with

number one above, consisting of the first 4 Nikayas and some of the

Khuddaka Nikaya as Buddhavacana.

See also: Original Buddhism

References

http://www.thedhamma.com/

The Authenticity of Early Buddhist Texts Buddhist Publication Society, 2014.

https://suttacentral.net/

dhammawiki.com

1-10 early to recent Chronology of Pali Canon - Dhamma Wiki

Thomas

William Rhys Davids in his Buddhist India (p. 188) has given a

chronological table of Buddhist literature from the time of the Buddha

to the time of Ashoka which is as follows:

Now Analytic Insight Net - FREE Online Tipiṭaka Research and Practice

University and related NEWS through http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org in

105 CLASSICAL LANGUAGES

an Online GOOD NEWS CHANNEL FOR WELFARE, HAPPINESS AND PEACE FOR ALL

SOCIETIES Catering to more than 3000 Emails: 200 WhatsApp, Facebook and

Twitter.

Saheb Kanshi Ram @SahebKanshiRam