Finland is an easy country to visit.

Finnish customs and manners are clearly European, with only a few

national variations, and attitudes are liberal. There is very little

chance of a visitor committing fundamental social gaffes or breaches of

etiquette that would fatally damage relations between himself and his

hosts. Such breaches are viewed by Finns with equanimity if committed by

their own countrymen and with understanding or amusement if committed

by foreigners. Codes of behaviour are fairly relaxed, and reputations –

good or bad – are built up over time as the result of personal actions

rather than conforming to norms or standards. It is difficult in Finland

to make or break a reputation with a single social blunder.

Finland is a country where considerable weight is attached to the

spoken word – words are chosen carefully and for the purpose of

delivering a message. Indeed, there are very few other culture-specific

considerations that visitors need be aware of. Finns place great value

on words, which is reflected in the tendency to say little and avoid

‘unnecessary’ small talk. As the Chinese proverb puts it, “Your speech

should be better than silence, if it is not, be silent.”

Identity

Finns

have a strong sense of national identity. They would be happy if

visitors knew something about the achievements of well-known Finns in

sports and culture.

Finns have a very strong sense of national identity. This is rooted

in the country’s history – particularly its honourable wartime

achievements and significant sporting merits – and is today nurtured by

pride in Finland’s high-tech expertise. Being realists, Finns do not

expect foreigners to know a lot about their country and its prominent

people, past or present, so they will be pleased if a visitor is

familair with at least some of the milestones of Finnish history or the

sports careers of Paavo Nurmi and Lasse Viren. Finns would be happy if

visitors knew something about the achievements of Finnish rally drivers

and Formula 1 stars, or if they knew that footballers Jari Litmanen and

Sami Hyypiä are Finns. Culturally oriented Finns will take it for

granted that like-minded visitors are familiar not only with Sibelius

but with contemporary composers Kaija Saariaho and Magnus Lindberg, and

orchestral conductors Esa-Pekka Salonen, Jukka-Pekka Saraste, Sakari

Oramo and Osmo Vänskä. While Finns are aware that Nokia is often

mistakenly thought to be a Japanese company, this misconception is

viewed forgivingly but with pity. They are proud that Linus Torvalds,

the inventor of Linux, is a Finn.

Visitors should also be prepared to encounter the other side of the

Finnish national character: Finns are chronically insecure about whether

the wider world is aware of the achievements of this northern nation.

Finns love reading things written about them abroad, and visitors should

not feel uncomfortable being asked repeatedly what they think of

Finland. However, although Finns are ready enough to criticize their own

country, they do not necessarily wish to hear visitors doing so.

Religion

Most

Finns belong to the Evangelical-Lutheran Church while a fraction of

them belong to the Orthodox Church. The Evangelical-Lutheran Church

accepts the ordination of women as priests.

As far as religion is concerned, there are very few dangers for

visitors to Finland, even on subjects that in other cultures might be

particularly sensitive. Most Finns belong formally to the

Evangelical-Lutheran Church (about 83%), while 1.1% belong to the

Finnish Orthodox Church; but people in general are fairly secular in

their views. Despite this, the Church and its ministers are held in high

esteem, and personal religious views are respected. It is difficult to

observe differences between believers and everyone else in everyday

life, except perhaps that the former lead more abstemious lives.

The number of immigrants in Finland is growing, and increasing

contacts with other religions in recent years have increased the Finns’

knowledge of them, although there is still much to be desired in their

tolerance for people with different religions and cultures.

Gender

There is a high degree of equality between the sexes in Finland, as

can be seen in the relatively high number of women holding advanced

positions in politics and other areas of society.

There are numerous women in academic posts, and in recent years

visiting businessmen have also found increasing numbers of ‘the fairer

sex’ on the other side of the negotiating table. The

Evangelical-Lutheran Church of Finland accepts the ordination of women,

and there are women priests in numerous parishes. The first female

Finnish bishop in the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland is Irja

Askola. She is reigning Bishop of Helsinki since 2010.

Chauvinistic or patronizing attitudes towards women are generally

considered unacceptable, although such attitudes do persist in practice.

Women do appreciate traditional courtesy, although ultimately they

appraise men on the basis of their attitude towards equality. Women are

usually independent financially and may offer to pay their share of a

restaurant bill, for instance. A man may politely refuse such an offer,

but it is equally polite to accept it.

In international contexts, or when using foreign languages,

particularly English, Finns have become accustomed to politically

correct language in which traditional masculine terms are replaced with

gender-neutral ones (e.g. ‘chairperson’); or the third person singular

pronoun is offered in both forms (he/she) when they exist. In Finnish

the latter problem does not exist. Instead, the third person singular

pronoun hän covers both genders. There are also many titles ending with the suffix –mies

(man) that are not considered gender-specific. It is appropriate for

visitors to follow the established practice of whatever language they

are using.

Conversing

The conception that Finns are a reserved and taciturn lot is an

ancient one and does not retain the same validity as it used to,

certainly not with the younger generations. Nevertheless, it is fair to

say that Finns have a special attitude to words and speech: words are

taken seriously, and people are held to what they say. “Take a man by

his words and a bull by its horns,” says a Finnish proverb. A Finn will

carefully consider what he (or she) says and expect others to do so too.

He (or she) considers verbal agreements and promises binding, not only

upon himself but upon the other party too, and he (or she) considers

that the value of words remains essentially the same, regardless of when

and where they are uttered. Visitors should remember that invitations

or wishes expressed in a light conversational manner (such as: “We must

have lunch together sometime”) are often taken at face value, and

forgetting them can cause concern. Small talk, a skill at which Finns

are notoriously lacking, is considered suspect by definition, and is not

especially valued.

Finns rarely enter into conversation with strangers, unless a

particularly strong impulse prompts it. As foreigners often note, Finns

are curiously silent in the metro, the bus or the tram. In lifts, they

suffer from the same mute embarrassment as everyone else in the world.

However, a visitor clutching a map will have no trouble in getting

advice on a street corner or in any other public place, since the

hospitality of Finns easily overrides their customary reserve.

Finns are better at listening than at talking, and interrupting

another speaker is considered impolite. A Finn does not grow nervous if

there are breaks in the conversation; silence is regarded as a part of

communication. Finns usually speak unhurriedly, even in their mother

tongue (the pace of newsreading on Finnish TV is a source of amusement

for many foreigners), and although many Finns are competent in several

foreign languages, they may be wary of the speed at which these

languages are spoken. Nevertheless, Finns can become excited and

voluble, given the right situation.

Having once got to know a stranger moderately well, Finns are quite

willing to discuss any topic; generally not even religion or politics

are taboo. Finland is one of the world’s leaders in the reading of books

and newspapers and the use of libraries, and thus the average Finn is

fairly well informed on what is happening in Finland and in the world.

Finland’s membership of the EU has increased interest in other EU

countries, and the common currency, the status of agriculture and the

effects of Community legislation are viable topics of conversation

wherever two or three Union citizens come together. Though Finns enjoy

bitching about the niggling directives of ‘Brussels bureaucrats’ as much

as the next man, in general they seem to approve of EU membership and

recognise its benefits.

Shared hobbies are a natural topic for conversation and exchange of

opinions in Finland as elsewhere, and it can be easy to strike up a

lively conversation with a Finn about culture and the arts on the one

hand and about sports on the other. Sports is a particularly feasible

topic because in recent years Finns have enjoyed success in sports other

than the traditional long-distance running and winter sports: there are

now world-class Finnish footballers, racing drivers and alpine skiers,

and consequently amateurs and enthusiasts in these fields too. Golf has

established itself securely especially among urban Finns, even though

they are obliged to abandon this pastime for the winter months. This

deprivation is an eminently suitable topic for conversation on the part

of a visitor who is familiar with the world of drivers and putters.

Information technology

The now ubiquitous mobile phone is revolutionizing the image of

Finnish communication skills. The persistent, supposedly amusing ringing

tones of the phones demonstrate how eager people are to talk to each

other, especially when they are not face to face. One foreign journalist

described a scene that he considered typically Finnish: a lone man

sitting in a bar with a beer and speaking into a cell phone. A Finnish

version of small talk? Communication without intimacy?

The use of mobile phones is governed in Finland, as indeed in other

countries, by a loosely defined etiquette which forbids their use if

disruptive or dangerous, so using a mobile phone is completely forbidden

on aeroplanes and in hospitals. During meetings it is inappropriate. In

pubs and restaurants it may be regarded by many as irritating but it

goes on regardless. At concerts, at the theatre and in church it is

barbaric and considerate people switch their phones off in those places.

Mobile phones have no doubt changed visitors’ perceptions of Finland.

Whereas a few decades ago a visitor might report back home on an

uncommunicative, reserved and introvert Arctic tribe, the more common

view today is that of a hyper-communicative people who are already

experiencing the future that some fear and others hope for: a society

where anyone can reach anyone else, no matter where or when.

All over the world, the Internet and e-mail have radically changed

how people find information and keep in touch, and Finland is no

exception. For young people, using the ever-increasing range of IT

applications is commonplace, and it is also an important factor in

shaping youth culture. Increasingly, politicians and corporate managers

set up websites and maintain personal blogs to comment publicly on their

lives and views.

Languages

A Finn’s mother tongue is either Finnish, Swedish (5.6% of the

population are Swedish speakers) or Saami (some 8,000 native speakers).

Finnish belongs to the small Finno-Ugrian language group; outside

Finland it is understood (and to some extent spoken) in Estonia. And in

Sweden, too, Finnish is spoken among the large number of Finnish

immigrants. Finns take care of their linguistic communication by

maintaining a wide range of foreign languages in the school curriculum.

English is widely spoken in Finland and in the business community

some companies use it as their house language. German is no longer

widely taught but many Finns in their 50s or older learned it as their

first foreign language at school. French, Spanish and Russian have grown

in popularity both in schools and among adult learners. Membership of

the European Union and the related practical and social demands have

increased the need to study European languages, at least in the case of

Finns who travel in Europe on business or are studying abroad.

Educated Finnish speakers, particularly those working in the public

sector, speak Swedish to some degree whilst almost all Swedish-speaking

Finns speak Finnish too. Only in some coastal areas and in the

autonomous province of the Åland Islands is Swedish the dominant

language, indeed in Åland it is the only official language. The status

of Swedish as the joint official language of mainland Finland can be

seen in the bilingual names of public institutions and in street signs,

the latter case depending on the percentage of minority language

speakers resident in a given municipality, and in the Swedish-language

programmes on radio and TV. Swedish-speaking Finns have a distinctive

culture, and their social mores are influenced by Scandinavian

traditions moreso than amongst the Finnish-speaking majority.

Names and titles

When introducing themselves, Finns will say their forename followed

by their surname. Women who use both their maiden name and their

husband’s surname will state them in that order. Although Finns are

conscious and proud of any official titles they may have, they rarely

mention these when introducing themselves. In contrast, they do expect

to be addressed by their title in professional and official contexts:

Doctor Virtanen, Managing Director Savolainen, etc. Foreigners, however,

are not expected to follow this practice, with the exception of the

titles “doctor” and “professor” if these are known to the speaker.

Otherwise, foreigners can safely address Finns using the English

practice of calling them Mr, Mrs, Miss, Ms, Sir or Madam, as

appropriate.

The familiar form of address in Finnish (i.e. the second person singular pronoun sinä, as opposed to the formal second person plural pronoun te)

is commonly used, not just between friends and acquaintances but among

strangers too. It is usual nowadays for people in a workplace to address

each other as sinä, up to and including senior management, at

least in larger workplaces. Using sinä is common today in service

occupations, too, although older people may resent the implied

familiarity. However, young people still tend to address middle-aged or

elderly people by the formal second person plural if they do not know

the persons well.

Although the use of the familiar sinä is common, using first

names requires a closer relationship. It is relatively easy to get onto

first-name terms with a Finn, especially if it is evident that the

parties will continue to meet regularly for business or pleasure.

However, it is felt appropriate that the use of first names is

specifically and mutually agreed upon. The use of first names is always

proposed by the older or more senior person to the junior, or, in the

case of equals, by the woman to the man; the agreement is enacted by

shaking hands, making eye contact, with each party saying their first

name aloud, and nodding the head. Raising a toast with schnapps, wine or

champagne lends a festive air to the occasion.

Apart from this, Finns are not nearly as demanding in remembering

names as many other people are. It is not usual to address people by

name when greeting them (regardless of how familiar one is with them) or

in the course of a normal conversation. Addressing by name has trickled

into Finnish culture from the American practice, but as nice as it is

to hear one’s name spoken, Finns will not be offended if they are not

addressed by name.

Businessmen and persons in public office are expected to distribute

business cards as a means of ensuring their name and title are

remembered. There are no special rituals related to exchanging business

cards in Finland. For a visitor, receiving a business card provides a

convenient opportunity to ask how a name is pronounced or what a cryptic

title might mean.

Greeting

When meeting, Finns shake hands and make eye contact. Handshakes are brief and firm, and involve no supporting gestures.

When greeting, the parties shake hands and make eye contact. A deep

bow denotes special respect – in normal circumstances, a nod of the head

is enough. A Finnish handshake is brief and firm, and involves no

supporting gestures such as touching the shoulder or upper arm. When

greeting a married couple, the wife should be greeted first, except on a

formal occasion where the hosts should first be greeted by the spouse

to whom the invitation was addressed. Children are greeted by shaking

hands too. Embracing people when greeting them is rare in Finland. A man

greeting someone in the street should raise his hat; in the cold of

winter, a touch of the hand to the brim of the hat is enough.

Finns can kiss as well as the next nation, but they rarely do so when

greeting. Hand-kissing is rare. Friends and acquaintances may hug when

meeting, and kisses on the cheek are not entirely unknown, although this

habit is not generally found in rural areas. There is no special

etiquette regarding the number of kisses on the cheek; however, most

Finns feel that three kisses is going a bit far. Men very rarely kiss

each other in greeting, and never on the mouth in the manner of our

eastern neighbours.

Eating

Finnish cuisine has western European, Scandinavian and Russian

elements. Table manners are European. Breakfast can be quite

substantial. Lunch is usually eaten between 11.00 and 13.00, a typical

lunch break at work lasting less than an hour. The once common long

business lunches have shrunk to 90 minutes or two hours. Evening meals

at home are eaten around 17.00-18.00. In most restaurants, dinners are

served from 18.00 onwards. Many restaurants stop serving food about 45

minutes before they actually close, so it is worthwhile checking the

serving times when booking a table. Concerts and theatre performances

usually begin at 19.00, and audiences adjourn to restaurants at around

22.00.

Restaurant menus and home cooking rarely involve food that western

visitors would not be acquainted with. Increased nutritional awareness

has made the once heavy, fatty Finnish diet lighter, and the better

restaurants can cater for a variety of dietary requirements. Ethnic

restaurants, constantly increasing in number, have added to the

expanding choice. Beer and wine are drunk with restaurant food in the

evening, but at lunchtime these days they feature very little, if at

all.

At a dinner party, the host determines the seating order if

necessary. The guest of honour is seated to the right of the hostess (or

the host, if it is a men-only dinner). This is a seat dreaded by most

Finns, since the guest of honour is expected to say a few words of

thanks to the hosts after the meal. Guests should not begin to eat until

everyone has been served; usually, the host will propose a toast at the

beginning of the meal, wishing his guests hyvää ruokahalua, the Finnish for bon appétit! It is not appropriate for guests to drink before this, unless the beginning of the meal is badly delayed.

Finns seldom make speeches during a meal, but they do so on formal

occasions. In such cases, the speeches are made between courses. During

the meal, the host may toast individual guests, or guests may toast each

other, by raising their glasses and making eye contact. Once the toast

is drunk, eye contact should be made again when lowering the glass to

the table.

A meal normally concludes with coffee and postprandial drinks are

served with it or immediately after. If the hosts allow smoking, this is

the moment to bring out the cigars and cigarettes, unless of course the

host has already allowed or suggested this earlier. When leaving the

table, the guests should thank the hosts briefly for the fare when they

get the chance, regardless of whether the guest of honour has done so or

not.

Drinking

It’s

time for a cup of coffee. Finns drink coffee anywhere and everywhere.

More coffee per person is drunk in Finland than anywhere else in the

world.

Finns consume the equivalent of slightly over ten litres of pure

alcohol per person per year, which is close to the European average.

Drinking habits mainly follow Scandinavian and European practices. There

are fewer national characteristics than one might think, considering

that Finns do have a reputation for drinking; and indeed binge drinking

is fairly common, as it is throughout northern Europe and parts of the

UK.

However, consumption of wine and beer, as opposed to spirits, has

increased in recent years, and as a result more decorous drinking

behaviour has become more common. Consumption of alcohol at lunchtime is

less common in the business world than it used to be, and in the public

sector it is extremely rare.

Alcohol consumption varies somewhat, according to socio-economic

differences and, to some extent, by region. The influence of central

European or Mediterranean drinking habits is primarily visible among

urban middle class young adults and slightly older Finns with tertiary

education.

The import and sale of wines and other alcoholic beverages is largely

controlled by the state-owned Alko organisation, and private

individuals can only buy alcoholic beverages in Alko shops, with the

exception of medium strength beer and cider, which can be bought in food

stores. Alko is a major buyer of wines and stocks a wide and

geographically representative selection of all qualities, including top

labels. Many restaurants import their own wines directly from suppliers

abroad.

In households wine is normally reserved for weekend meals, but meals

prepared for guests or eaten in a restaurant usually involve wine. Often

– and in the case of Swedish-speaking Finns, almost always – a meal is

preceded by schnapps, a shot of vodka or aquavit in a tiny glass. This

is considered an integral part of cold fish courses, and absolutely

essential with crayfish. Swedish-speaking Finns have a custom of

enlivening the occasion with a line or two of a drinking song before

each shot of schnapps. Big dinner parties have an appointed toastmaster

who determines the interval between shots and leads the singing.

Finnish-speaking Finns have a less elaborate and less structured

drinking etiquette, although there are schnapps songs in Finnish too.

Schnapps is usually accompanied by mineral water, or sometimes beer,

which is also commonly served with meals. Beer is also used to slake the

thirst created by the sauna.

Visitors can approach Finnish drinking customs as they see fit. It is

not necessary to drink a shot of schnapps in one gulp even if your

neighbour does. So it is enough to raise the glass to one’s lips without

swallowing. It is also perfectly acceptable to request mineral water or

non-alcoholic wine with a meal. Lunch is usually accompanied by

non-alcoholic beverages in any case, and non-alcoholic drinks are

usually provided. Abstinence is also supported by legislation; in

Finland, the blood alcohol level for drunken driving is very low, and

the penalties are severe.

Tipping

Tipping has never fitted very comfortably into the Finnish way of

life. This may have originally been due to the traditions of a religion

which emphasized frugality; today, the rather blunt reason for not

tipping is that the price paid includes any unusual instances of service

or politeness i.e. the view taken is that “service is included”.

Tipping does nevertheless exist in Finland, and you can feel safe that

while nobody will object to being tipped, very few will mind not being

tipped.

As a rule, service is included in restaurant bills. However, an extra

service charge is often added to bills which are to be paid by a

customers’ employers. Those who pay for their own meals and in cash

often choose to round the bill up to the nearest convenient figure. This

does not require any complicated arithmetic from the customer, as no

one cares whether the tip really is 10-15% of the total bill.

Tipping at hotels is fairly rare. If you know that you have caused

extra inconvenience for the room cleaner, it would be regarded as an

appropriate to leave a tip. Receptionists should be tipped only by

long-term guests at the hotel. Like their colleagues across the world,

Finnish hotel porters will be glad to be tipped the price of a small

beer. It is also OK to leave a few coins on the bar for the bar staff.

Taxi drivers do not expect to get a tip, but customers often pay the

nearest rounded up figure to the actual fare. Major credit cards are

usually accepted in taxis, and in this case tipping in cash is

practical.

If you are the guest of Finnish hosts, you should leave any tipping to their discretion.

Smoking

Smoking has decreased in recent years, and attitudes towards it have

become more negative. The law prohibits smoking in public buildings and

workplaces and, being generally law-abiding, Finns have adapted to this

legislation. Nevertheless, smoking is still quite common, in all age

groups. International trends have increased the popularity of cigars

amongst a minority of tobacco smokers.

As have many other countries, Finland has banned smoking in most restaurants and other licensed premises completely.

Smokers are expected to be considerate. When invited to a private

home, a guest should ask the hosts if they object to smoking, even if

there are ashtrays visible. Smokers may be guided to the balcony, which

may have the effect of reducing the intake of nicotine considerably in

cold weather.

Visiting

The home is to a great extent the focus of social life in Finland –

to a greater extent at least than in countries where it is more common

to meet over a meal in a restaurant. There are cultural, and also

economic, reasons for this. A growing interest in cooking and wines has

led to an increase in entertaining in the home. A foreign visitor need

have no qualms about being invited into someone’s home; he can expect a

fairly relaxed and informal atmosphere, and sending or bringing a bunch

of flowers or a bottle of wine for the hosts will be appreciated.

A greater cultural challenge for the visitor is accepting an

invitation to one of the innumerable summer dwellings that dot the

seashores and lakeshores of Finland. One in four Finns owns a summer

cabin, and for many, it is regarded as a second home. Sociologists like

to explain that the summer dwelling is a tie that Finns maintain to

their rural past; and it is true that many Finns transform into

surprisingly competent fishermen, gardeners, farmers, carpenters or

foresters when they withdraw to their summer homes.

A guest is not expected to take part in this role-play, at least not

actively. On the other hand, he is expected to submit without complaint

to the sometimes primitive conditions at the summer residence, since not

all of them have electricity, running water, a flushing toilet or other

urban amenities Many families consider that even a TV set is

incompatible with genuine summer cabin life.

A guest is expected to dress casually but practically when going to a

summer cabin. The hosts will have rubber boots, raincoats and

windcheaters that are worn as the weather dictates or when going

fishing, picking mushrooms or walking in the forest. An experienced

guest understands that under these conditions the hosts, particularly

the hostess, have to go to a lot of trouble to give the guest an

enjoyable stay. Help with routine chores is greatly appreciated: peeling

the potatoes or the onions is a job the guest can safely offer to

undertake.

The best reward for the hosts is that guests enjoy themselves, rain

or shine. As for correctness, it would be polite for a guest to raise

the question of departure at breakfast time on the third day, and only

agree to stay longer if the hosts protest with particular conviction.

Time and the seasons

Although seasons occur everywhere, in Finland they mark the progress

of the year with striking conspicuousness. Extending far beyond the

Arctic Circle, Finland enjoys such extremes of temperature and daylight

that it would not be too far-fetched to say that there are two cultures

in Finland: one dominated by the almost perpetual daylight of the summer

sun and surprisingly high temperatures, and the other characterized by

mercilessly cold winters and Arctic gloom that only briefly gives way to

twilight during the day.

Even though summer comes every year, it is considered so important

that virtually the entire country ‘shuts down’ for the five or six weeks

that follow Midsummer, which falls in late June. After Midsummer, Finns

move en masse to their vacation homes in the countryside and those who

do not spend their time out of doors, in street cafés and bars, in parks

and on beaches, being social and feeling positive. Business and

personal correspondence may be temporarily shelved, e-mails cheerfully

return ‘out of the office’ notifications for a month or more, and

conversations between acquaintances revolve more around how the fish are

biting or how the garden is doing than around important issues of

international politics or the economy. It is easy for a visitor to

observe that in summer Finns are especially proud and happy to be Finns

and to live in Finland, and encouraging these feelings is welcome.

With the advent of winter, Finns close down their summer dwellings,

store their boats in dry dock, put snow tyres on their cars, stash their

golf gear in the basement and check their skis. Whereas the rural

ancestors of today’s Finns whiled away the long winter days in making

and repairing tools for summer, their descendants labour in offices to

make their country an increasingly efficient and modern high-tech

marvel.

Finns are punctual people and, in one sense, prisoners of time. As is

the case elsewhere in the world, those holding the most demanding jobs

have tight daily schedules; missing appointments can cause anguish.

Agreed meeting times are scrupulously observed, to the minute if at all

possible, and being over 15 minutes late is considered impolite and

requires a brief apology or an explanation. Concerts, theatre

performances and other public functions begin on time, and delays in

domestic rail and bus traffic are rare.

In general, busy lifestyles have come to stay and a diary full of

meetings and negotiations is a matter of pride and a status symbol in

Finland rather than a demonstration of poor scheduling. In such an

environment, the time allocated for the entertaining of guests is one of

the most important indicators of the value attached to the occasion.

When a Finn stops glancing at his watch and suggests something more to

eat or drink, or even a sauna, the visitor can rest assured that a

lasting business relationship, or friendship, is on the cards.

Festivals

Finns

move to their vacation homes after Midsummer. One in four Finns owns a

“mökki”, a holiday cabin. Finns take a dip in the lake after sauna, and

finish the bathing session with sausage and beer.

Finns like celebrations and Finland’s calendar of official festivals

is not very different from that of other European countries. One major

difference is that the Protestant Lutheran calendar does not accommodate

all the feast days of Catholic tradition. Visitors may find it strange

that Finns have calm and serious festivities on occasions that would be

boisterous and joyful in continental Europe.

Christmas, and Christmas Eve in particular, is very much a family

festival in Finland, usually spent at home or with relatives. Customs

include lighting candles by the graves of deceased family members. Finns

wish each other ‘Merry Christmas’, but equally often they say ‘Peaceful

Christmas’. Christmas Day is generally a quiet day and Christmastide

social life does not restart until Boxing Day.

December 6 is Independence Day, an occasion marked with solemn

ceremonial observances. It is a day for remembering those who fell in

the wars to protect Finland’s independence, which was achieved in1917.

In the evening, the President of the Republic hosts a reception for some

2,000 guests – including the diplomatic corps accredited to Finland –

and watching this reception on TV has evolved into a favourite pastime

for the entire nation.

In wintertime, Shrove Tuesday is just about the only festive occasion

where public merrymaking can be observed, though even this is not even a

pale reflection of the carnivals held in more southerly lands.

Logically enough, the most flamboyant annual parties in Finland occur at

a warmer time of year. May Day, internationally a festival day for

workers and students, can with justification be described as a northern

version of Mardi Gras, and Midsummer – the ‘night of no night’ – is an

occasion for uninhibited rejoicing, as for most Finns it marks the

beginning of summer holidays and a move to the summer dwelling in the

countryside.

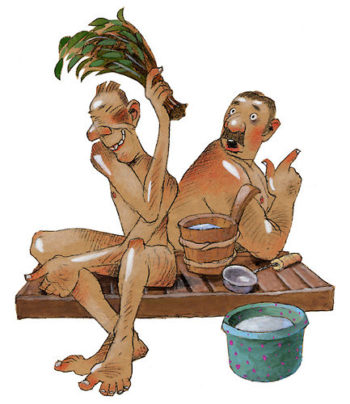

The sauna

Having

a sauna is something completely natural to Finns. A first timer should

perhaps have a first encounter with the sauna in the company of a

genuine Finn.

A nation of five million people with 1.5 million saunas has no need

to acquire a formal sauna education – learning to bathe in the sauna

comes as naturally as learning to speak. Visitors would do well to have

their first encounter with the sauna in the company of a Finnish friend

or acquaintance, rather than following a mechanical set of instructions

that reduces sauna bathing to a drill by numbers.

In Finland, both men and women bathe in the sauna, but never together

except within the family. There are no mixed public saunas in Finland. A

visitor hesitant about having a sauna should remember that if it has

been heated specially for him or her, it is a matter of pride for the

hosts, and only medical constraints are an acceptable reason for not

trying it.

Having a sauna is something natural to all Finns, yet people do have

their own ways of bathing in the sauna. But Finn would never say to

another that he is ‘doing it wrong’. It is a matter of preference. This

is a good principle to follow for the visitor too: listen to your own

body and follow your own rhythm in moving between the hot room, the

washing room and the open air, perhaps including the lake or the sea. It

is helpful to follow what others are doing, but avoid extremes: some

Finns feel the need to demonstrate their tenacity by sitting in a

scalding hot sauna for inordinately long periods. In such a situation, a

wise visitor will quietly slip out to consume some liquid and enjoy the

scenery. On the other hand, it can be equally rewarding to surrender to

unknown rituals with an open mind. The feeling of being slapped on the

skin with a bundle of soft birch leaves in the heat of the steam room

can be a pleasant therapeutic experience.

The sauna is no place for anyone in a hurry. When the bathing is

over, it is customary to continue the occasion with conversation, drinks

and perhaps a light meal. A guest’s comments on the sauna experience

will be listened to with interest, After all, this is a subject that

Finns never tire of talking about.

By professor Olli Alho, November 2002, updated March 2010

Illustrations by Mika Launis