Discovery of Metteyya Awakened One with Awareness Universe (FOAINDMAOAU)

Current Situation Ends between 04-8-2020 and 3-12-2020 which Paves way for Free Online Analytical Insight Net

For

The Welfare, Happiness, Peace of All Sentient and Non-Sentient Beings and for them to Attain Eternal Peace as Final Goal.

From

KUSHINARA NIBBANA BHUMI PAGODA

in 116 CLASSICAL LANGUAGES

Through

http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org

At

WHITE HOME

668, 5A main Road, 8th Cross, HAL III Stage,

Prabuddha Bharat Puniya Bhumi Bengaluru

Magadhi Karnataka State

PRABUDDHA BHARAT

DO GOOD PURIFY MIND AND ENVIRONMENTWords of the Metteyya Awakened One with Awareness

from

Free Online step by step creation of Virtual tour in 3D Circle-Vision 360° for Kushinara Nibbana Bhumi Pagoda

Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Sutta in Classical Devanagari,Classical Hindi-Devanagari- शास्त्रीय हिंदी

https://srv1.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

Last updated: June 30, 2020, 02:33 GMT

Coronavirus Cases:

10,408,433

Deaths:

508,078

7,794,770,907

Current World Population-40,382,525 Net population growth this year-

79,241 Net population growth today 69,603,91 Births this year-136,581

Births today-Recovered:5,664,407 from COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic

a whole new spin to the term ‘world music’ — A.R.Rahman spins his

magic on an absolute scorcher, featuring Jordanian singer –Farah Siraj

along with Nepalese Buddhist Nun Ani Choying. With the traditional

Nepalese Buddhist hymn forming the base of the song, layered with a

traditional Jordanian melody, and bridged seamlessly with composition

written by A.R.Rahman, this song truly brings together diverse cultures

and musical genres. Everything from the background vocals to Sivamani’s

percussion takes a big leap across musical styles and creates a storm of

inspired rhythms, to give this track that extra flavour. Completely

based around the theme of motherhood, compassion & ultimately

happiness, this is the very first track of what promises to be an

unforgettable Season 3 of CS@MTV!

Vocals: Abhilasha Chellum, Deblina Bose, Kanika Joshi, Prajakta Shukre,

Sasha Trupati , Varsha Tripathy, Aditi Pual, Suchi, Rayhanah, Issrath

Quadhri

always my great honor to play music with respected Ani Choying Drolma.

this video is recorded at a live concert in Taiwan in 2015 organized by

Tibetan culture society in Taiwan.M y deep Gratitude to Tibetan culture

society and the Cultural Department of Taiwan Government for great

Support to make this event possible and great success.

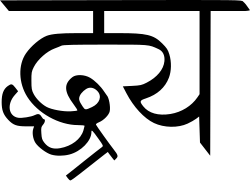

देवनागरी

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

| देवनागरी लिपि |

|

|---|---|

देवनागरी लिपि (ऊपर स्वर है, नीचे व्यंजन है) छन्दस फॉण्ट में |

|

| प्रकार | आबूगीदा |

| भाषाएँ | अपभ्रंश, अवधी, भीली, भोजपुरी, बोड़ो, ब्रजभाषा, छत्तीसगढ़ी, डोगरी, गुजराती, हरियाणवी, हिन्दी, हिन्दुस्तानी, कन्नड़, कश्मीरी, कोंकणी, कोशली ओड़िया, मगही, मैथिली, मराठी, मारवाड़ी, मुंडारी, नेवा, नेपाली, पालि, पहाड़ी (विविध), प्राकृत, पंजाबी, राजस्थानी, सादरी, संस्कृत, संताली, सराइकी, शेर्पा, सिन्धी, सूरजापुरी, उर्दू और बहुत सारे |

| समय अवधि | पूर्व संकेत: पहली शताब्दी ई.,[1] आधुनिक रूप: 10 वीं शताब्दी ई.[2][3] |

| जनक प्रणाली | |

| बाल प्रणालियाँ |

गुजराती मोड़ी |

| Sister systems | नन्दिनागरी |

| आईएसओ 15924 | Deva, 315 |

| दिशा | बाएँ-से-दाएँ |

| यूनिकोड एलियास | Devanagari |

| यूनिकोड रेंज |

U+0900–U+097F देवनागरी, U+A8E0–U+A8FF देवनागरी विस्तारित, U+1CD0–U+1CFF वैदिक विस्तार |

|

[क] ब्राह्मी लिपियों का सॅमॅटिक से मूल, सार्वभौमिक रूप से सहमत नहीं है।

नोट: इस पृष्ठ पर आइपीए ध्वन्यात्मक प्रतीक हो सकते हैं। |

|

| देवनागरी |

|---|

|

देवनागरी एक भारतीय लिपि है जिसमें अनेक भारतीय भाषाएँ तथा कई विदेशी भाषाएँ लिखी जाती हैं। यह बायें से दायें लिखी जाती है। इसकी पहचान एक क्षैतिज रेखा से है जिसे ‘शिरोरेखा’ कहते हैं। संस्कृत, पालि, हिन्दी, मराठी, कोंकणी, सिन्धी, कश्मीरी, हरियाणवी, डोगरी, खस, नेपाल भाषा (तथा अन्य नेपाली भाषाएँ), तमांग भाषा, गढ़वाली, बोडो, अंगिका, मगही, भोजपुरी, नागपुरी, मैथिली, संताली, राजस्थानी बघेली आदि भाषाएँ और स्थानीय बोलियाँ भी देवनागरी में लिखी जाती हैं। इसके अतिरिक्त कुछ स्थितियों में गुजराती, पंजाबी, बिष्णुपुरिया मणिपुरी, रोमानी और उर्दू भाषाएँ भी देवनागरी में लिखी जाती हैं। देवनागरी विश्व में सर्वाधिक प्रयुक्त लिपियों में से एक है। यह दक्षिण एशिया की १७० से अधिक भाषाओं को लिखने के लिए प्रयुक्त हो रही है। [4]

परिचय

अधिकतर भाषाओं की तरह देवनागरी भी बायें से दायें लिखी जाती है। प्रत्येक शब्द के ऊपर एक रेखा खिंची होती है (कुछ वर्णों के ऊपर रेखा नहीं होती है) इसे शिरोरेखा कहते हैं। देवनागरी का विकास ब्राह्मी लिपि से हुआ है। यह एक ध्वन्यात्मक लिपि है जो प्रचलित लिपियों (रोमन, अरबी, चीनी आदि) में सबसे अधिक वैज्ञानिक है। इससे वैज्ञानिक और व्यापक लिपि शायद केवल अध्वव लिपि है। भारत की कई लिपियाँ देवनागरी से बहुत अधिक मिलती-जुलती हैं, जैसे- बांग्ला, गुजराती, गुरुमुखी आदि। कम्प्यूटर प्रोग्रामों की सहायता से भारतीय लिपियों को परस्पर परिवर्तन बहुत आसान हो गया है।

भारतीय भाषाओं के किसी भी शब्द या ध्वनि को देवनागरी लिपि में ज्यों का त्यों लिखा जा सकता है और फिर लिखे पाठ को लगभग ‘हू-ब-हू’ उच्चारण किया जा सकता है, जो कि रोमन लिपि और अन्य कई लिपियों में सम्भव नहीं है, जब तक कि उनका विशेष मानकीकरण न किया जाये, जैसे आइट्रांस या IAST ।

इसमें कुल ५२ अक्षर हैं, जिसमें १४ स्वर और ३८ व्यंजन हैं। अक्षरों की क्रम व्यवस्था (विन्यास) भी बहुत ही वैज्ञानिक है। स्वर-व्यंजन, कोमल-कठोर, अल्पप्राण-महाप्राण, अनुनासिक्य-अन्तस्थ-उष्म इत्यादि वर्गीकरण भी वैज्ञानिक हैं। एक मत के अनुसार देवनगर (काशी) मे प्रचलन के कारण इसका नाम देवनागरी पड़ा।

भारत तथा एशिया की अनेक लिपियों के संकेत देवनागरी से अलग हैं पर उच्चारण व वर्ण-क्रम आदि देवनागरी के ही समान हैं, क्योंकि वे सभी ब्राह्मी लिपि से उत्पन्न हुई हैं (उर्दू को छोड़कर)। इसलिए इन लिपियों को परस्पर आसानी से लिप्यन्तरित किया जा सकता है। देवनागरी लेखन की दृष्टि से सरल, सौन्दर्य की दृष्टि से सुन्दर और वाचन की दृष्टि से सुपाठ्य है।

‘देवनागरी’ शब्द की व्युत्पत्ति

देवनागरी

या नागरी नाम का प्रयोग “क्यों” प्रारम्भ हुआ और इसका व्युत्पत्तिपरक

प्रवृत्तिनिमित्त क्या था- यह अब तक पूर्णतः निश्चित नहीं है।

(क) ‘नागर’ अपभ्रंश या गुजराती “नागर” ब्राह्मणों से उसका संबंध बताया गया है। पर दृढ़ प्रमाण के अभाव में यह मत संदिग्ध है।

(ख) दक्षिण में इसका प्राचीन नाम “नंदिनागरी” था। हो सकता है “नंदिनागर” कोई स्थानसूचक हो और इस लिपि का उससे कुछ संबंध रहा हो।

(ग) यह भी हो सकता है कि “नागर” जन इसमें लिखा करते थे, अत: “नागरी” अभिधान पड़ा और जब संस्कृत के ग्रंथ भी इसमें लिखे जाने लगे तब “देवनागरी” भी कहा गया।

(घ) सांकेतिक चिह्नों या देवताओं की उपासना में प्रयुक्त

त्रिकोण, चक्र आदि संकेतचिह्नों को “देवनागर” कहते थे। कालांतर में नाम के

प्रथमाक्षरों का उनसे बोध होने लगा और जिस लिपि में उनको स्थान मिला- वह

‘देवनागरी’ या ‘नागरी’ कही गई। इन सब पक्षों के मूल में कल्पना का

प्राधान्य है, निश्चयात्मक प्रमाण अनुपलब्ध हैं।

इतिहास

देवनागरी, भारत, नेपाल, तिब्बत और दक्षिण पूर्व एशिया की लिपियों के ब्राह्मी लिपि परिवार का हिस्सा है।[5][6] गुजरात से कुछ अभिलेख प्राप्त हुए हैं जिनकी भाषा संस्कृत है और लिपि नागरी लिपि। ये अभिलेख पहली ईसवी से लेकर चौथी ईसवी के कालखण्ड के हैं।[7]

ध्यातव्य है कि नागरी लिपि, देवनागरी से बहुत निकट है और देवनागरी का

पूर्वरूप है। अतः ये अभिलेख इस बात के साक्ष्य हैं कि प्रथम शताब्दी में भी

भारत में देवनागरी का उपयोग आरम्भ हो चुका था। नागरी, सिद्धम और शारदा तीनों ही ब्राह्मी की वंशज हैं।[8] रुद्रदमन

के शिलालेखों का समय प्रथम शताब्दी का समय है और इसकी लिपि की देवनागरी से

निकटता पहचानी जा सकती हैं। जबकि देवनागरी का जो वर्तमान मानक स्वरूप है,

वैसी देवनागरी का उपयोग १००० ई के पहले आरम्भ हो चुका था। [9][10]

मध्यकाल के शिलालेखों के अध्ययन से स्पष्ट होता है कि नागरी से

सम्बन्धित लिपियों का बड़े पैमाने पर प्रसार होने लगा था। कहीं-कहीं

स्थानीय लिपि और नागरी लिपि दोनों में सूचनाएँ अंकित मिलतीं हैं। उदाहरण

के लिए, ८वीं शताब्दी के पट्टदकल

(कर्नाटक) के स्तम्भ पर सिद्धमात्रिका और तेलुगु-कन्नड लिपि के आरम्भिक

रूप - दोनों में ही सूचना लिखी हुई है। कांगड़ा (हिमाचल प्रदेश) के

ज्वालामुखी अभिलेख में शारदा और देवनागरी दोनों में लिखा हुआ है। [11]

७वीं शताब्दी तक देवनागरी का नियमित रूप से उपयोग होना आरम्भ हो गया था और लगभग १००० ई तक देवनागरी का पूर्ण विकास हो गया था।[12][13]

डॉ॰ द्वारिका प्रसाद सक्सेना के अनुसार सर्वप्रथम देवनागरी लिपि का प्रयोग गुजरात के नरेश जयभट्ट (700-800 ई.) के शिलालेख में मिलता है। आठवीं शताब्दी में चित्रकूट, नवीं में बड़ौदा के ध्रुवराज भी अपने राज्यादेशों में इस लिपि का उपयोग किया हैं।

758 ई. का राष्ट्रकूट राजा दन्तिदुर्ग का सामगढ़ ताम्रपट मिलता है जिस पर देवनागरी अंकित है। शिलाहारवंश के गंडारादित्य प्रथम के उत्कीर्ण लेख की लिपि देवनागरी है। इसका समय बारहवीं शताब्दी हैं। ग्यारहवीं शताब्दी के चोलराजा राजेन्द्र के सिक्के मिले हैं जिन पर देवनागरी लिपि अंकित है। राष्ट्रकूट राजा इंद्रराज (दसवीं शताब्दी) के लेख में भी देवनागरी का व्यवहार किया है। प्रतिहार राजा महेंद्रपाल (891-907) का दानपत्र भी देवनागरी लिपि में है।

कनिंघम की पुस्तक में सबसे प्राचीन मुसलमानों सिक्के के रूप में महमूद गजनवी द्वारा चलाये गए चांदी के सिक्के का वर्णन है जिस पर देवनागरी लिपि में संस्कृत अंकित है। मुहम्मद विनसाम (1192-1205) के सिक्कों पर लक्ष्मी की मूर्ति के साथ देवनागरी लिपि का व्यवहार हुआ है। शम्सुद्दीन इल्तुतमिश (1210-1235) के सिक्कों पर भी देवनागरी अंकित है। सानुद्दीन फिरोजशाह प्रथम, जलालुद्दीन रज़िया, बहराम शाह, अलाऊद्दीन मसूदशाह, नासिरुद्दीन महमूद, मुईजुद्दीन, गयासुद्दीन बलवन, मुईजुद्दीन कैकूबाद, जलालुद्दीन हीरो सानी, अलाउद्दीन महमद शाह आदि ने अपने सिक्कों पर देवनागरी अक्षर अंकित किये हैं। अकबर के सिक्कों पर देवनागरी में ‘राम‘ सिया का नाम अंकित है। गयासुद्दीन तुग़लक़, शेरशाह सूरी, इस्लाम शाह, मुहम्मद आदिलशाह, गयासुद्दीन इब्ज, ग्यासुद्दीन सानी आदि ने भी इसी परम्परा का पालन किया।

भाषाविज्ञान की दृष्टि से देवनागरी

भाषावैज्ञानिक दृष्टि से देवनागरी लिपि अक्षरात्मक (सिलेबिक) लिपि मानी जाती है। लिपि के विकाससोपानों की दृष्टि से “चित्रात्मक“, “भावात्मक” और “भावचित्रात्मक” लिपियों के अनंतर “अक्षरात्मक”

स्तर की लिपियों का विकास माना जाता है। पाश्चात्य और अनेक भारतीय

भाषाविज्ञानविज्ञों के मत से लिपि की अक्षरात्मक अवस्था के बाद अल्फाबेटिक

(वर्णात्मक) अवस्था का विकास हुआ। सबसे विकसित अवस्था मानी गई है

ध्वन्यात्मक (फोनेटिक) लिपि की। “देवनागरी” को अक्षरात्मक इसलिए कहा जाता

है कि इसके वर्ण- अक्षर (सिलेबिल) हैं- स्वर भी और व्यंजन भी। “क”, “ख” आदि

व्यंजन सस्वर हैं- अकारयुक्त हैं। वे केवल ध्वनियाँ नहीं हैं अपितु सस्वर

अक्षर हैं। अत: ग्रीक, रोमन आदि वर्णमालाएँ हैं। परंतु यहाँ यह ध्यान रखने

की बात है कि भारत की “ब्राह्मी” या “भारती” वर्णमाला की ध्वनियों में

व्यंजनों का “पाणिनि” ने वर्णसमाम्नाय के 14 सूत्रों में जो स्वरूप परिचय दिया है- उसके विषय में “पतंजलि”

(द्वितीय शताब्दी ई.पू.) ने यह स्पष्ट बता दिया है कि व्यंजनों में

संनियोजित “अकार” स्वर का उपयोग केवल उच्चारण के उद्देश्य से है। वह तत्वत:

वर्ण का अंग नहीं है। इस दृष्टि से विचार करते हुए कहा जा सकता है कि इस लिपि की वर्णमाला तत्वत: ध्वन्यात्मक है, अक्षरात्मक नहीं।

देवनागरी वर्णमाला

देवनागरी की वर्णमाला में १२ स्वर और ३४ व्यंजन हैं। शून्य या एक या अधिक व्यंजनों और एक स्वर के मेल से एक अक्षर बनता है।

स्वर

निम्नलिखित स्वर आधुनिक हिन्दी (खड़ी बोली) के लिये दिये गये हैं। संस्कृत में इनके उच्चारण थोड़े अलग होते हैं।

| वर्णाक्षर | “प” के साथ मात्रा | IPA उच्चारण | “प्” के साथ उच्चारण | IAST समतुल्य | हिन्दी में वर्णन |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| अ | प | / ə / | / pə / | a | बीच का मध्य प्रसृत स्वर |

| आ | पा | / α: / | / pα: / | ā | दीर्घ विवृत पश्व प्रसृत स्वर |

| इ | पि | / i / | / pi / | i | ह्रस्व संवृत अग्र प्रसृत स्वर |

| ई | पी | / i: / | / pi: / | ī | दीर्घ संवृत अग्र प्रसृत स्वर |

| उ | पु | / u / | / pu / | u | ह्रस्व संवृत पश्व वर्तुल स्वर |

| ऊ | पू | / u: / | / pu: / | ū | दीर्घ संवृत पश्व वर्तुल स्वर |

| ए | पे | / e: / | / pe: / | e | दीर्घ अर्धसंवृत अग्र प्रसृत स्वर |

| ऐ | पै | / æ: / | / pæ: / | ai | दीर्घ लगभग-विवृत अग्र प्रसृत स्वर |

| ओ | पो | / ο: / | / pο: / | o | दीर्घ अर्धसंवृत पश्व वर्तुल स्वर |

| औ | पौ | / ɔ: / | / pɔ: / | au | दीर्घ अर्धविवृत पश्व वर्तुल स्वर |

| <कुछ भी नही> | <कुछ भी नही> | / ɛ / | / pɛ / | <कुछ भी नहीं> | ह्रस्व अर्धविवृत अग्र प्रसृत स्वर |

संस्कृत में ऐ दो स्वरों का युग्म होता है और “अ-इ” या “आ-इ” की तरह बोला जाता है। इसी तरह औ “अ-उ” या “आ-उ” की तरह बोला जाता है।

इसके अलावा हिन्दी और संस्कृत में य

- ऋ — आधुनिक हिन्दी में “रि” की तरह

- ॠ — केवल संस्कृत में

- ऌ — केवल संस्कृत में

- ॡ — केवल संस्कृत में

- अं — आधे न् , म् , ङ् , ञ् , ण् के लिये या स्वर का नासिकीकरण करने के लिये

- अँ — स्वर का नासिकीकरण करने के लिये

- अः — अघोष “ह्” (निःश्वास) के लिये

- ऍ और ऑ — इनका उपयोग मराठी और और कभी-कभी हिन्दी में अंग्रेजी शब्दों का निकटतम उच्चारण तथा लेखन करने के लिये किया जाता है।

व्यंजन

जब किसी स्वर प्रयोग नहीं हो, तो वहाँ पर ‘अ’ (अर्थात श्वा का स्वर) माना जाता है। स्वर के न होने को हलन्त् अथवा विराम से दर्शाया जाता है। जैसे कि क् ख् ग् घ्।

जिन वर्णो को बोलने के लिए स्वर की सहायता लेनी पड़ती है उन्हें व्यंजन कहते है।

दूसरे शब्दो में- व्यंजन उन वर्णों को कहते हैं, जिनके उच्चारण में स्वर वर्णों की सहायता ली जाती है।

जैसे- क, ख, ग, च, छ, त, थ, द, भ, म इत्यादि।

|

|

अल्पप्राण अघोष |

महाप्राण अघोष |

अल्पप्राण घोष |

महाप्राण घोष |

नासिक्य |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| कण्ठ्य | क / kə / |

ख / khə / |

ग / gə / |

घ / gɦə / |

ङ / ŋə / |

| तालव्य | च / cə / या / tʃə / |

छ / chə / या /tʃhə/ |

ज / ɟə / या / dʒə / |

झ / ɟɦə / या / dʒɦə / |

ञ / ɲə / |

| मूर्धन्य | ट / ʈə / |

ठ / ʈhə / |

ड / ɖə / |

ढ / ɖɦə / |

ण / ɳə / |

| दन्त्य | त / t̪ə / |

थ / t̪hə / |

द / d̪ə / |

ध / d̪ɦə / |

न / nə / |

| ओष्ठ्य | प / pə / |

फ / phə / |

ब / bə / |

भ / bɦə / |

म / mə / |

|

|

तालव्य | मूर्धन्य | दन्त्य/ वर्त्स्य |

कण्ठोष्ठ्य/ काकल्य |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| अन्तस्थ | य / jə / |

र / rə / |

ल / lə / |

व / ʋə / |

| ऊष्म/ संघर्षी |

श / ʃə / |

ष / ʂə / |

स / sə / |

ह / ɦə / या / hə / |

- नोट करें -

- इनमें से ळ (मूर्धन्य पार्विक अन्तस्थ) एक अतिरिक्त व्यंजन

है जिसका प्रयोग हिन्दी में नहीं होता है। मराठी, वैदिक संस्कृत, कोंकणी,

मेवाड़ी, इत्यादि में सभी का प्रयोग किया जाता है।

- संस्कृत में ष का उच्चारण ऐसे होता था : जीभ की नोक को मूर्धा (मुँह की छत) की ओर उठाकर श जैसी आवाज़ करना। शुक्ल यजुर्वेद की माध्यंदिनि शाखा में कुछ वाक़्यात में ष का उच्चारण ख की तरह करना मान्य था। आधुनिक हिन्दी में ष का उच्चारण पूरी तरह श की तरह होता है।

- हिन्दी में ण का उच्चारण

ज़्यादातर ड़ँ की तरह होता है, यानि कि जीभ मुँह की छत को एक ज़ोरदार ठोकर

मारती है। हिन्दी में क्षणिक और क्शड़िंक में कोई फ़र्क नहीं। पर संस्कृत

में ण का उच्चारण न की तरह बिना ठोकर मारे होता था, अन्तर केवल इतना कि जीभ

ण के समय मुँह की छत को छूती है।

नुक़्ता वाले व्यंजन

हिन्दी भाषा में मुख्यत: अरबी और फ़ारसी

भाषाओं से आये शब्दों को देवनागरी में लिखने के लिये कुछ वर्णों के नीचे

नुक्ता (बिन्दु) लगे वर्णों का प्रयोग किया जाता है (जैसे क़, ज़ आदि)।

किन्तु हिन्दी में भी अधिकांश लोग नुक्तों का प्रयोग नहीं करते। इसके अलावा

संस्कृत, मराठी, नेपाली एवं अन्य भाषाओं को देवनागरी में लिखने में भी

नुक्तों का प्रयोग नहीं किया जाता है।

| वर्णाक्षर (IPA उच्चारण) | उदाहरण | वर्णन | अंग्रेज़ी में वर्णन | ग़लत उच्चारण |

| क़ (/ q /) | क़त्ल | अघोष अलिजिह्वीय स्पर्श | Voiceless uvular stop | क (/ k /) |

| ख़ (/ x or χ /) | ख़ास | अघोष अलिजिह्वीय या कण्ठ्य संघर्षी | Voiceless uvular or velar fricative | ख (/ kh /) |

| ग़ (/ ɣ or ʁ /) | ग़ैर | घोष अलिजिह्वीय या कण्ठ्य संघर्षी | Voiced uvular or velar fricative | ग (/ g /) |

| फ़ (/ f /) | फ़र्क | अघोष दन्त्यौष्ठ्य संघर्षी | Voiceless labio-dental fricative | फ (/ ph /) |

| ज़ (/ z /) | ज़ालिम | घोष वर्त्स्य संघर्षी | Voiced alveolar fricative | ज (/ dʒ /) |

| झ़ (/ ʒ /) | टेलेवीझ़न | घोष तालव्य संघर्षी | Voiced palatal fricative | ज (/ dʒ /) |

| थ़ (/ θ /) | अथ़्रू | अघोष दन्त्य संघर्षी | Voiceless dental fricative | थ (/ t̪h /) |

| ड़ (/ ɽ /) | पेड़ | अल्पप्राण मूर्धन्य उत्क्षिप्त | Unaspirated retroflex flap | - |

| ढ़ (/ ɽh /) | पढ़ना | महाप्राण मूर्धन्य उत्क्षिप्त | Aspirated retroflex flap | - |

थ़ का प्रयोग मुख्यतः पहाड़ी भाषाओँ

में होता है जैसे की डोगरी (की उत्तरी उपभाषाओं) में “आंसू” के लिए शब्द है

“अथ़्रू”। हिन्दी में ड़ और ढ़ व्यंजन फ़ारसी या अरबी से नहीं लिये गये

हैं, न ही ये संस्कृत में पाये जाये हैं। असल में ये संस्कृत के साधारण ड

और ढ के बदले हुए रूप हैं।

विराम-चिह्न, वैदिक चिह्न आदि

| प्रतीक |

नाम |

कार्य |

|---|---|---|

| । | डण्डा / खड़ी पाई / पूर्ण विराम |

वाक्य का अन्त बताने के लिये |

| ॥ | दोहरा डण्डा |

|

| ॰ | संक्षिप्तीकरण के लिये, जैसे मो॰ क॰ गाँधी | |

| ॐ | प्रणव , ओम | हिन्दू धर्म का शुभ शब्द |

| प॑ | उदात्त | उच्चारण बताने के लिये वैदिक संस्कृत के कुछ ग्रन्थों में प्रयुक्त |

| प॒ | अनुदात्त | उच्चारण बताने के लिये वैदिक संस्कृत के कुछ ग्रन्थों में प्रयुक्त |

देवनागरी अंक

देवनागरी अंक निम्न रूप में लिखे जाते हैं :

| ० | १ | २ | ३ | ४ | ५ | ६ | ७ | ८ | ९ |

देवनागरी संयुक्ताक्षर

देवनागरी लिपि में दो व्यंजन का संयुक्ताक्षर निम्न रूप में लिखा जाता है :

| क | ख | ग | घ | ङ | च | छ | ज | झ | ञ | ट | ठ | ड | ढ | ण | त | थ | द | ध | न | प | फ | ब | भ | म | य | र | ल | व | श | ष | स | ह | ळ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| क | क्क | क्ख | क्ग | क्घ | क्ङ | क्च | क्छ | क्ज | क्झ | क्ञ | क्ट | क्ठ | क्ड | क्ढ | क्ण | क्त | क्थ | क्द | क्ध | क्न | क्प | क्फ | क्ब | क्भ | क्म | क्य | क्र | क्ल | क्व | क्श | क्ष | क्स | क्ह | क्ळ |

| ख | ख्क | ख्ख | ख्ग | ख्घ | ख्ङ | ख्च | ख्छ | ख्ज | ख्झ | ख्ञ | ख्ट | ख्ठ | ख्ड | ख्ढ | ख्ण | ख्त | ख्थ | ख्द | ख्ध | ख्न | ख्प | ख्फ | ख्ब | ख्भ | ख्म | ख्य | ख्र | ख्ल | ख्व | ख्श | ख्ष | ख्स | ख्ह | ख्ळ |

| ग | ग्क | ग्ख | ग्ग | ग्घ | ग्ङ | ग्च | ग्छ | ग्ज | ग्झ | ग्ञ | ग्ट | ग्ठ | ग्ड | ग्ढ | ग्ण | ग्त | ग्थ | ग्द | ग्ध | ग्न | ग्प | ग्फ | ग्ब | ग्भ | ग्म | ग्य | ग्र | ग्ल | ग्व | ग्श | ग्ष | ग्स | ग्ह | ग्ळ |

| घ | घ्क | घ्ख | घ्ग | घ्घ | घ्ङ | घ्च | घ्छ | घ्ज | घ्झ | घ्ञ | घ्ट | घ्ठ | घ्ड | घ्ढ | घ्ण | घ्त | घ्थ | घ्द | घ्ध | घ्न | घ्प | घ्फ | घ्ब | घ्भ | घ्म | घ्य | घ्र | घ्ल | घ्व | घ्श | घ्ष | घ्स | घ्ह | घ्ळ |

| ङ | ंक | ंख | ंग | ंघ | ंङ | ंच | ंछ | ंज | ंझ | ंञ | ंट | ंठ | ंड | ंढ | ंण | ंत | ंथ | ंद | ंध | ंन | ंप | ंफ | ंब | ंभ | ंम | ंय | ंर | ंल | ंव | ंश | ंष | ंस | ंह | ंळ |

| च | च्क | च्ख | च्ग | च्घ | च्ङ | च्च | च्छ | च्ज | च्झ | च्ञ | च्ट | च्ठ | च्ड | च्ढ | च्ण | च्त | च्थ | च्द | च्ध | च्न | च्प | च्फ | च्ब | च्भ | च्म | च्य | च्र | च्ल | च्व | च्श | च्ष | च्स | च्ह | च्ळ |

| छ | छ्क | छ्ख | छ्ग | छ्घ | छ्ङ | छ्च | छ्छ | छ्ज | छ्झ | छ्ञ | छ्ट | छ्ठ | छ्ड | छ्ढ | छ्ण | छ्त | छ्थ | छ्द | छ्ध | छ्न | छ्प | छ्फ | छ्ब | छ्भ | छ्म | छ्य | छ्र | छ्ल | छ्व | छ्श | छ्ष | छ्स | छ्ह | छ्ळ |

| ज | ज्क | ज्ख | ज्ग | ज्घ | ज्ङ | ज्च | ज्छ | ज्ज | ज्झ | ज्ञ | ज्ट | ज्ठ | ज्ड | ज्ढ | ज्ण | ज्त | ज्थ | ज्द | ज्ध | ज्न | ज्प | ज्फ | ज्ब | ज्भ | ज्म | ज्य | ज्र | ज्ल | ज्व | ज्श | ज्ष | ज्स | ज्ह | ज्ळ |

| झ | झ्क | झ्ख | झ्ग | झ्घ | झ्ङ | झ्च | झ्छ | झ्ज | झ्झ | झ्ञ | झ्ट | झ्ठ | झ्ड | झ्ढ | झ्ण | झ्त | झ्थ | झ्द | झ्ध | झ्न | झ्प | झ्फ | झ्ब | झ्भ | झ्म | झ्य | झ्र | झ्ल | झ्व | झ्श | झ्ष | झ्स | झ्ह | झ्ळ |

| ञ | ंक | ंख | ंग | ंघ | ंङ | ंच | ंछ | ंज | ंझ | ंञ | ंट | ंठ | ंड | ंढ | ंण | ंत | ंथ | ंद | ंध | ंन | ंप | ंफ | ंब | ंभ | ंम | ंय | ंर | ंल | ंव | ंश | ंष | ंस | ंह | ंळ |

| ट | ट्क | ट्ख | ट्ग | ट्घ | ट्ङ | ट्च | ट्छ | ट्ज | ट्झ | ट्ञ | ट्ट | ट्ठ | ट्ड | ट्ढ | ट्ण | ट्त | ट्थ | ट्द | ट्ध | ट्न | ट्प | ट्फ | ट्ब | ट्भ | ट्म | ट्य | ट्र | ट्ल | ट्व | ट्श | ट्ष | ट्स | ट्ह | ट्ळ |

| ठ | ठ्क | ठ्ख | ठ्ग | ठ्घ | ठ्ङ | ठ्च | ठ्छ | ठ्ज | ठ्झ | ठ्ञ | ठ्ट | ठ्ठ | ठ्ड | ठ्ढ | ठ्ण | ठ्त | ठ्थ | ठ्द | ठ्ध | ठ्न | ठ्प | ठ्फ | ठ्ब | ठ्भ | ठ्म | ठ्य | ठ्र | ठ्ल | ठ्व | ठ्श | ठ्ष | ठ्स | ठ्ह | ठ्ळ |

| ड | ड्क | ड्ख | ड्ग | ड्घ | ड्ङ | ड्च | ड्छ | ड्ज | ड्झ | ड्ञ | ड्ट | ड्ठ | ड्ड | ड्ढ | ड्ण | ड्त | ड्थ | ड्द | ड्ध | ड्न | ड्प | ड्फ | ड्ब | ड्भ | ड्म | ड्य | ड्र | ड्ल | ड्व | ड्श | ड्ष | ड्स | ड्ह | ड्ळ |

| ढ | ढ्क | ढ्ख | ढ्ग | ढ्घ | ढ्ङ | ढ्च | ढ्छ | ढ्ज | ढ्झ | ढ्ञ | ढ्ट | ढ्ठ | ढ्ड | ढ्ढ | ढ्ण | ढ्त | ढ्थ | ढ्द | ढ्ध | ढ्न | ढ्प | ढ्फ | ढ्ब | ढ्भ | ढ्म | ढ्य | ढ्र | ढ्ल | ढ्व | ढ्श | ढ्ष | ढ्स | ढ्ह | ढ्ळ |

| ण | ण्क | ण्ख | ण्ग | ण्घ | ण्ङ | ण्च | ण्छ | ण्ज | ण्झ | ण्ञ | ण्ट | ण्ठ | ण्ड | ण्ढ | ण्ण | ण्त | ण्थ | ण्द | ण्ध | ण्न | ण्प | ण्फ | ण्ब | ण्भ | ण्म | ण्य | ण्र | ण्ल | ण्व | ण्श | ण्ष | ण्स | ण्ह | ण्ळ |

| त | त्क | त्ख | त्ग | त्घ | त्ङ | त्च | त्छ | त्ज | त्झ | त्ञ | त्ट | त्ठ | त्ड | त्ढ | त्ण | त्त | त्थ | त्द | त्ध | त्न | त्प | त्फ | त्ब | त्भ | त्म | त्य | त्र | त्ल | त्व | त्श | त्ष | त्स | त्ह | त्ळ |

| थ | थ्क | थ्ख | थ्ग | थ्घ | थ्ङ | थ्च | थ्छ | थ्ज | थ्झ | थ्ञ | थ्ट | थ्ठ | थ्ड | थ्ढ | थ्ण | थ्त | थ्थ | थ्द | थ्ध | थ्न | थ्प | थ्फ | थ्ब | थ्भ | थ्म | थ्य | थ्र | थ्ल | थ्व | थ्श | थ्ष | थ्स | थ्ह | थ्ळ |

| द | द्क | द्ख | द्ग | द्घ | द्ङ | द्च | द्छ | द्ज | द्झ | द्ञ | द्ट | द्ठ | द्ड | द्ढ | द्ण | द्त | द्थ | द्द | द्ध | द्न | द्प | द्फ | द्ब | द्भ | द्म | द्य | द्र | द्ल | द्व | द्श | द्ष | द्स | द्ह | द्ळ |

| ध | ध्क | ध्ख | ध्ग | ध्घ | ध्ङ | ध्च | ध्छ | ध्ज | ध्झ | ध्ञ | ध्ट | ध्ठ | ध्ड | ध्ढ | ध्ण | ध्त | ध्थ | ध्द | ध्ध | ध्न | ध्प | ध्फ | ध्ब | ध्भ | ध्म | ध्य | ध्र | ध्ल | ध्व | ध्श | ध्ष | ध्स | ध्ह | ध्ळ |

| न | न्क | न्ख | न्ग | न्घ | न्ङ | न्च | न्छ | न्ज | न्झ | न्ञ | न्ट | न्ठ | न्ड | न्ढ | न्ण | न्त | न्थ | न्द | न्ध | न्न | न्प | न्फ | न्ब | न्भ | न्म | न्य | न्र | न्ल | न्व | न्श | न्ष | न्स | न्ह | न्ळ |

| प | प्क | प्ख | प्ग | प्घ | प्ङ | प्च | प्छ | प्ज | प्झ | प्ञ | प्ट | प्ठ | प्ड | प्ढ | प्ण | प्त | प्थ | प्द | प्ध | प्न | प्प | प्फ | प्ब | प्भ | प्म | प्य | प्र | प्ल | प्व | प्श | प्ष | प्स | प्ह | प्ळ |

| फ | फ्क | फ्ख | फ्ग | फ्घ | फ्ङ | फ्च | फ्छ | फ्ज | फ्झ | फ्ञ | फ्ट | फ्ठ | फ्ड | फ्ढ | फ्ण | फ्त | फ्थ | फ्द | फ्ध | फ्न | फ्प | फ्फ | फ्ब | फ्भ | फ्म | फ्य | फ्र | फ्ल | फ्व | फ्श | फ्ष | फ्स | फ्ह | फ्ळ |

| ब | ब्क | ब्ख | ब्ग | ब्घ | ब्ङ | ब्च | ब्छ | ब्ज | ब्झ | ब्ञ | ब्ट | ब्ठ | ब्ड | ब्ढ | ब्ण | ब्त | ब्थ | ब्द | ब्ध | ब्न | ब्प | ब्फ | ब्ब | ब्भ | ब्म | ब्य | ब्र | ब्ल | ब्व | ब्श | ब्ष | ब्स | ब्ह | ब्ळ |

| भ | भ्क | भ्ख | भ्ग | भ्घ | भ्ङ | भ्च | भ्छ | भ्ज | भ्झ | भ्ञ | भ्ट | भ्ठ | भ्ड | भ्ढ | भ्ण | भ्त | भ्थ | भ्द | भ्ध | भ्न | भ्प | भ्फ | भ्ब | भ्भ | भ्म | भ्य | भ्र | भ्ल | भ्व | भ्श | भ्ष | भ्स | भ्ह | भ्ळ |

| म | म्क | म्ख | म्ग | म्घ | म्ङ | म्च | म्छ | म्ज | म्झ | म्ञ | म्ट | म्ठ | म्ड | म्ढ | म्ण | म्त | म्थ | म्द | म्ध | म्न | म्प | म्फ | म्ब | म्भ | म्म | म्य | म्र | म्ल | म्व | म्श | म्ष | म्स | म्ह | म्ळ |

| य | य्क | य्ख | य्ग | य्घ | य्ङ | य्च | य्छ | य्ज | य्झ | य्ञ | य्ट | य्ठ | य्ड | य्ढ | य्ण | य्त | य्थ | य्द | य्ध | य्न | य्प | य्फ | य्ब | य्भ | य्म | य्य | य्र | य्ल | य्व | य्श | य्ष | य्स | य्ह | य्ळ |

| र | र्क | र्ख | र्ग | र्घ | र्ङ | र्च | र्छ | र्ज | र्झ | र्ञ | र्ट | र्ठ | र्ड | र्ढ | र्ण | र्त | र्थ | र्द | र्ध | र्न | र्प | र्फ | र्ब | र्भ | र्म | र्य | र्र | र्ल | र्व | र्श | र्ष | र्स | र्ह | र्ळ |

| ल | ल्क | ल्ख | ल्ग | ल्घ | ल्ङ | ल्च | ल्छ | ल्ज | ल्झ | ल्ञ | ल्ट | ल्ठ | ल्ड | ल्ढ | ल्ण | ल्त | ल्थ | ल्द | ल्ध | ल्न | ल्प | ल्फ | ल्ब | ल्भ | ल्म | ल्य | ल्र | ल्ल | ल्व | ल्श | ल्ष | ल्स | ल्ह | ल्ळ |

| व | व्क | व्ख | व्ग | व्घ | व्ङ | व्च | व्छ | व्ज | व्झ | व्ञ | व्ट | व्ठ | व्ड | व्ढ | व्ण | व्त | व्थ | व्द | व्ध | व्न | व्प | व्फ | व्ब | व्भ | व्म | व्य | व्र | व्ल | व्व | व्श | व्ष | व्स | व्ह | व्ळ |

| श | श्क | श्ख | श्ग | श्घ | श्ङ | श्च | श्छ | श्ज | श्झ | श्ञ | श्ट | श्ठ | श्ड | श्ढ | श्ण | श्त | श्थ | श्द | श्ध | श्न | श्प | श्फ | श्ब | श्भ | श्म | श्य | श्र | श्ल | श्व | श्श | श्ष | श्स | श्ह | श्ळ |

| ष | ष्क | ष्ख | ष्ग | ष्घ | ष्ङ | ष्च | ष्छ | ष्ज | ष्झ | ष्ञ | ष्ट | ष्ठ | ष्ड | ष्ढ | ष्ण | ष्त | ष्थ | ष्द | ष्ध | ष्न | ष्प | ष्फ | ष्ब | ष्भ | ष्म | ष्य | ष्र | ष्ल | ष्व | ष्श | ष्ष | ष्स | ष्ह | ष्ळ |

| स | स्क | स्ख | स्ग | स्घ | स्ङ | स्च | स्छ | स्ज | स्झ | स्ञ | स्ट | स्ठ | स्ड | स्ढ | स्ण | स्त | स्थ | स्द | स्ध | स्न | स्प | स्फ | स्ब | स्भ | स्म | स्य | स्र | स्ल | स्व | स्श | स्ष | स्स | स्ह | स्ळ |

| ह | ह्क | ह्ख | ह्ग | ह्घ | ह्ङ | ह्च | ह्छ | ह्ज | ह्झ | ह्ञ | ह्ट | ह्ठ | ह्ड | ह्ढ | ह्ण | ह्त | ह्थ | ह्द | ह्ध | ह्न | ह्प | ह्फ | ह्ब | ह्भ | ह्म | ह्य | ह्र | ह्ल | ह्व | ह्श | ह्ष | ह्स | ह्ह | ह्ळ |

| ळ | ळ्क | ळ्ख | ळ्ग | ळ्घ | ळ्ङ | ळ्च | ळ्छ | ळ्ज | ळ्झ | ळ्ञ | ळ्ट | ळ्ठ | ळ्ड | ळ्ढ | ळ्ण | ळ्त | ळ्थ | ळ्द | ळ्ध | ळ्न | ळ्प | ळ्फ | ळ्ब | ळ्भ | ळ्म | ळ्य | ळ्र | ळ्ल | ळ्व | ळ्श | ळ्ष | ळ्स | ळ्ह | ळ्ळ |

ब्राह्मी परिवार की लिपियों

में देवनागरी लिपि सबसे अधिक संयुक्ताक्षरों को समर्थन देती है। देवनागरी २

से अधिक व्यंजनों के संयुक्ताक्षर को भी समर्थन देती है। छन्दस फॉण्ट देवनागरी में बहुत संयुक्ताक्षरों को समर्थन देता है।

पुरानी देवनागरी

पुराने समय में प्रयुक्त हुई जाने वाली देवनागरी के कुछ वर्ण आधुनिक देवनागरी से भिन्न हैं।

| आधुनिक देवनागरी | पुरानी देवनागरी |

|---|---|

देवनागरी लिपि के गुण

- भारतीय भाषाओं के लिये वर्णों की पूर्णता एवं सम्पन्नता (५२ वर्ण, न बहुत अधिक न बहुत कम)।

- एक ध्वनि के लिये एक सांकेतिक चिह्न — जैसा बोलें वैसा लिखें।

- लेखन और उच्चारण और में एकरुपता — जैसा किखें, वैसे पढ़े (वाचें)।

- एक सांकेतिक चिह्न द्वारा केवल एक ध्वनि का निरूपण — जैसा लिखें वैसा पढ़ें।

- उपरोक्त दोनों गुणों के कारण ब्राह्मी लिपि का उपयोग करने वाली सभी भारतीय भाषाएँ ‘स्पेलिंग की समस्या’ से मुक्त हैं।

- स्वर और व्यंजन में तर्कसंगत एवं वैज्ञानिक क्रम-विन्यास -

देवनागरी के वर्णों का क्रमविन्यास उनके उच्चारण के स्थान (ओष्ठ्य, दन्त्य,

तालव्य, मूर्धन्य आदि) को ध्यान में रखते हुए बनाया गया है। इसके अतिरिक्त

वर्ण-क्रम के निर्धारण में भाषा-विज्ञान

के कई अन्य पहलुओ का भी ध्यान रखा गया है। देवनागरी की वर्णमाला (वास्तव

में, ब्राह्मी से उत्पन्न सभी लिपियों की वर्णमालाएँ) एक अत्यन्त तर्कपूर्ण

ध्वन्यात्मक क्रम (phonetic order) में व्यवस्थित है। यह क्रम इतना

तर्कपूर्ण है कि अन्तरराष्ट्रीय ध्वन्यात्मक संघ (IPA) ने अन्तर्राष्ट्रीय ध्वन्यात्मक वर्णमाला के निर्माण के लिये मामूली परिवर्तनों के साथ इसी क्रम को अंगीकार कर लिया।

- वर्णों का प्रत्याहार रूप में उपयोग : माहेश्वर सूत्र

में देवनागरी वर्णों को एक विशिष्ट क्रम में सजाया गया है। इसमें से किसी

वर्ण से आरम्भ करके किसी दूसरे वर्ण तक के वर्णसमूह को दो अक्षर का एक छोटा

नाम दे दिया जाता है जिसे ‘प्रत्याहार’ कहते हैं। प्रत्याहार का प्रयोग

करते हुए सन्धि आदि के नियम अत्यन्त सरल और संक्षिप्त ढंग से दिए गये हैं (जैसे, आद् गुणः)

- देवनागरी लिपि के वर्णों का उपयोग संख्याओं को निरूपित करने के लिये किया जाता रहा है। (देखिये कटपयादि, भूतसंख्या तथा आर्यभट्ट की संख्यापद्धति)

- मात्राओं की संख्या के आधार पर छन्दों का वर्गीकरण :

यह भारतीय लिपियों की अद्भुत विशेषता है कि किसी पद्य के लिखित रूप से

मात्राओं और उनके क्रम को गिनकर बताया जा सकता है कि कौन सा छन्द है। रोमन,

अरबी एवं अन्य में यह गुण अप्राप्य है।

- लिपि चिह्नों के नाम और ध्वनि मे कोई अन्तर नहीं (जैसे रोमन में अक्षर का नाम “बी” है और ध्वनि “ब” है)

- लेखन और मुद्रण मे एकरूपता (रोमन, अरबी और फ़ारसी मे हस्तलिखित और मुद्रित रूप अलग-अलग हैं)

- देवनागरी, ‘स्माल लेटर” और ‘कैपिटल लेटर’ की अवैज्ञानिक व्यवस्था से मुक्त है।

- मात्राओं का प्रयोग

- अर्ध-अक्षर के रूप की सुगमता : खड़ी पाई को हटाकर - दायें

से बायें क्रम में लिखकर तथा अर्द्ध अक्षर को ऊपर तथा उसके नीचे पूर्ण

अक्षर को लिखकर - ऊपर नीचे क्रम में संयुक्ताक्षर बनाने की दो प्रकार की

रीति प्रचलित है।

- अन्य - बायें से दायें, शिरोरेखा, संयुक्ताक्षरों का

प्रयोग, अधिकांश वर्णों में एक उर्ध्व-रेखा की प्रधानता, अनेक ध्वनियों को

निरूपित करने की क्षमता आदि।[14]

- भारतवर्ष के साहित्य में कुछ ऐसे रूप विकसित हुए हैं जो दायें-से-बायें अथवा बाये-से-दायें पढ़ने पर समान रहते हैं। उदाहरणस्वरूप केशवदास का एक सवैया लीजिये :

-

- मां सस मोह सजै बन बीन, नवीन बजै सह मोस समा।

- मार लतानि बनावति सारि, रिसाति वनाबनि ताल रमा ॥

- मां सस मोह सजै बन बीन, नवीन बजै सह मोस समा।

-

- मानव ही रहि मोरद मोद, दमोदर मोहि रही वनमा।

- माल बनी बल केसबदास, सदा बसकेल बनी बलमा ॥

- मानव ही रहि मोरद मोद, दमोदर मोहि रही वनमा।

- इस सवैया की किसी भी पंक्ति को किसी ओर से भी पढिये, कोई अंतर नही पड़ेगा।

-

- सदा सील तुम सरद के दरस हर तरह खास।

- सखा हर तरह सरद के सर सम तुलसीदास॥

देवनागरी लिपि के दोष

देवनागरी लिपि की 10 कमियाँ !

1.ग, ण,और श में आकार लगे होने का भ्रम होता है !

2.वर्ण के प्रकार –

क, र ध्वनि-राजा,क्रम,कर्म,ट्रक,ऋण,कृपा

ख.द - दम,विद्या,छद्म,गद्दी

ग. क-कर,वक्त ,क्वाथ

घ .श-शाम,श्रम,श्याम

ङ.म-मन,म्यान,छद्म,ब्रह्म

च.भ-भवन,अभ्युक्ति,उद्भव,

3.संयुक्ताक्षर में आधे अक्षर बाएँ,दाएँ और नीचे लगते हैं-वह, व्यय, द्वार,जिह्वा!

4.शुद्ध

में द पूरा अक्षर लिखा है,लेकिन उच्चारण आधा होता है!ध आधा लिखा होता

है,लेकिन उच्चारण पूरा होता है !इसी तरह वृद्ध,श्रद्धा आदि!

5.शक्ति में क पर भी इकार लगता है!ऐसे ही निश्चित,बल्कि आदि!

6.द्विज का उच्चारण दु+वि+ज होता है!लिखने और पढ़ने दोनों में दुविधा होती है!

7.जो लिखा दिखता है वह उच्चारित नहीं होता है!और जो कहते हैं वह नहीं लिखा जाता है!

क.शुरू

में एकार लगा नहीं है लेकिन उच्चारित होता है! जैसे-क्या का उच्चारण के+या

होता है!इसी तरह-व्यय, प्यास,प्याज,ब्याज,व्यापार,व्यवस्था,व्यवहार,आदि!

ख.शुरू में ओकार नहीं लगा है,लेकिन उच्चारित होता है! जैसे-द्वार दो+वा+ र,द्वंद्व,ज्वर,त्वरित आदि!

8.शब्दों के उच्चारण के हिसाब से वर्णों का क्रम अस्पष्ट होता है!असमंजस की स्थिति रहती है!जैसे-क.वृद्ध उच्चारण वृ+द्+ध होता है!

ख.निर्देश

लिखे वर्ण का क्रम देखें तो नि+दे+र्+श उच्चारण के अनुसार ‘ दे ‘ के पहले ‘

र ‘ ध्वनि संकेत लिखा होना चाहिए ! लेकिन ऐसा नहीं है-दे के बाद र का

संकेत लगता है!

9.अनुनासिक

अनेक ध्वनि संकेतों के बदले सिर्फ अनुस्वार का प्रयोग होने के कारण ध्वनि

का गलत संकेत लिखा जा रहा है ! जैसे-अंत उच्चारित करें तो अ+न्+त=अन्त होता

है!इसी तरह कंपनी/कम्पनी,खंड/खन्ड/खण्ड आदि!

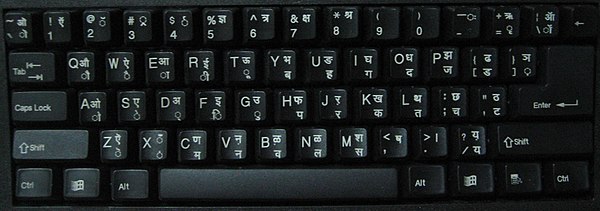

10.देवनागरी एक हजार साल पुरानी लिपि है!कम्प्यूटर से हिंदी टाइपिंग में लगभग140ध्वनि संकेतों की आवश्यकता होती है!

देवनागरी

लिपि से विकसित होडो़ सेंणा लिपि में उपर्युक्त सभी कमियों का समाधान

है!इस लिपि से मात्र 45 ध्वनि संकेत चिह्नों से शुद्ध वर्तनी लिखी जा सकती

है!सिर्फ हिंदी और मुंडा भाषाएँ ही नहीं,अनेक भारतीय भाषाएँ भी शुद्ध

वर्तनी के साथ लिखी जा सकती हैं !

रवीन्द्र नाथ सुलंकी

www.hindikinailipi.com

- (१) कुल मिलाकर 403 टाइप होने के कारण टंकण, मुद्रण में कठिनाई। किन्तु आधुनिक प्रिन्टर तकनीक के लिए यह कोई समस्या नहीं है।

- (२) कुछ लोग शिरोरेखा का प्रयोग अनावश्यक मानते हैं।

- (३) अनावश्यक वर्ण (ऋ, ॠ, लृ, ॡ, ष)— बहुत से लोग इनका शुद्ध उच्चारण नहीं कर पाते।

- (४) द्विरूप वर्ण (अ, ज्ञ, क्ष, त्र, छ, झ, ण, श) आदि को दो-दो प्रकार से लिखा जाता है।

- (५) समरूप वर्ण (ख में र+व का, घ में ध का, म में भ का भ्रम होना)।

- (६) वर्णों के संयुक्त करने की व्यवस्था एकसमान नहीं है।

- (८) त्वरापूर्ण लेखन नहीं क्योंकि लेखन में हाथ बार–बार उठाना पड़ता है।

- (९) वर्णों के संयुक्तीकरण में र के प्रयोग को लेकर अनेक लोगों को भ्रम की स्थिति।

- (११) इ की मात्रा (ि) का लेखन वर्ण के पहले, किन्तु उच्चारण वर्ण के बाद।

देवनागरी पर महापुरुषों के विचार

आचार्य विनोबा भावे

संसार की अनेक लिपियों के जानकार थे। उनकी स्पष्ट धारणा थी कि देवनागरी

लिपि भारत ही नहीं, संसार की सर्वाधिक वैज्ञानिक लिपि है। अगर भारत की सब

भाषाओं के लिए इसका व्यवहार चल पड़े तो सारे भारतीय एक दूसरे के बिल्कुल

नजदीक आ जाएंगे। हिंदुस्तान की एकता में देवनागरी लिपि हिंदी से ही अधिक

उपयोगी हो सकती है। अनन्त शयनम् अयंगार तो दक्षिण भारतीय भाषाओं के लिए भी देवनागरी की संभावना स्वीकार करते थे। सेठ गोविन्ददास इसे राष्ट्रीय लिपि घोषित करने के पक्ष में थे।

- (१) हिन्दुस्तान की एकता के लिये हिन्दी भाषा जितना काम देगी, उससे बहुत अधिक काम देवनागरी लिपि दे सकती है।

-

- — आचार्य विनोबा भावे

- (२) देवनागरी किसी भी लिपि की तुलना में अधिक वैज्ञानिक एवं व्यवस्थित लिपि है।

-

- — सर विलियम जोन्स

- (३) मानव मस्तिष्क से निकली हुई वर्णमालाओं में नागरी सबसे अधिक पूर्ण वर्णमाला है।

-

- — जान क्राइस्ट

- (४) उर्दू लिखने के लिये देवनागरी लिपि अपनाने से उर्दू उत्कर्ष को प्राप्त होगी।

-

- — खुशवन्त सिंह

- (५) The Devanagri alphabet is a splendid monument of phonological accuracy, in the sciences of language.

-

- — मोहन लाल विद्यार्थी - Indian Culture Through the Ages, p. 61

- (६) एक सर्वमान्य लिपि स्वीकार करने से भारत की विभिन्न भाषाओं में

जो ज्ञान का भंडार भरा है उसे प्राप्त करने का एक साधारण व्यक्ति को सहज

ही अवसर प्राप्त होगा। हमारे लिए यदि कोई सर्व-मान्य लिपि स्वीकार करना

संभव है तो वह देवनागरी है।

- (७) प्राचीन भारत के महत्तम उपलब्धियों में से एक उसकी विलक्षण

वर्णमाला है जिसमें प्रथम स्वर आते हैं और फिर व्यंजन जो सभी उत्पत्ति क्रम

के अनुसार अत्यंत वैज्ञानिक ढंग से वर्गीकृत किये गए हैं। इस वर्णमाला का

अविचारित रूप से वर्गीकृत तथा अपर्याप्त रोमन वर्णमाला से, जो तीन हजार वर्षों से क्रमशः विकसित हो रही थी, पर्याप्त अंतर है।

-

- — ए एल बाशम, “द वंडर दैट वाज इंडिया” के लेखक और इतिहासविद्

भारत के लिये देवनागरी का महत्व

|

|

इस लेख में सन्दर्भ या स्रोत नहीं दिया गया है। कृपया विश्वसनीय सन्दर्भ या स्रोत जोड़कर इस लेख में सुधार करें। स्रोतहीन सामग्री ज्ञानकोश के उपयुक्त नहीं है। इसे हटाया जा सकता है। |

बहुत से लोगों का विचार है कि भारत में अनेकों भाषाएँ होना कोई समस्या नहीं है जबकि उनकी लिपियाँ अलग-अलग होना बहुत बड़ी समस्या है। गांधीजी ने १९४० में गुजराती भाषा की एक पुस्तक को देवनागरी लिपि में छपवाया और इसका उद्देश्य बताया था कि मेरा सपना है कि संस्कृत से निकली हर भाषा की लिपि देवनागरी हो।[15]

- इस संस्करण को हिंदी में छापने के दो उद्देश्य हैं। मुख्य

उद्देश्य यह है कि मैं जानना चाहता हूँ कि, गुजराती पढ़ने वालों को

देवनागरी लिपि में पढ़ना कितना अच्छा लगता है। मैं जब दक्षिण अफ्रीका में

था तब से मेरा स्वप्न है कि संस्कृत से निकली हर भाषा की एक लिपि हो, और वह

देवनागरी हो। पर यह अभी भी स्वप्न ही है। एक-लिपि के बारे में बातचीत तो

खूब होती हैं, लेकिन वही ‘बिल्ली के गले में घंटी कौन बांधे’ वाली बात है।

कौन पहल करे ! गुजराती कहेगा ‘हमारी लिपि तो बड़ी सुन्दर सलोनी आसान है,

इसे कैसे छोडूंगा?’ बीच में अभी एक नया पक्ष और निकल के आया है, वह ये, कुछ

लोग कहते हैं कि देवनागरी खुद ही अभी अधूरी है, कठिन है; मैं भी यह मानता

हूँ कि इसमें सुधार होना चाहिए। लेकिन अगर हम हर चीज़ के बिलकुल ठीक हो

जाने का इंतज़ार करते रहेंगे तो सब हाथ से जायेगा, न जग के रहोगे न जोगी

बनोगे। अब हमें यह नहीं करना चाहिए। इसी आजमाइश के लिए हमने यह देवनागरी

संस्करण निकाला है। अगर लोग यह (देवनागरी में गुजराती) पसंद करेंगे तो

‘नवजीवन पुस्तक’ और भाषाओं को भी देवनागरी में प्रकाशित करने का प्रयत्न

करेगा।

- इस साहस के पीछे दूसरा उद्देश्य यह है कि हिंदी पढ़ने वाली जनता

गुजराती पुस्तक देवनागरी लिपि में पढ़ सके। मेरा अभिप्राय यह है कि अगर

देवनागरी लिपि में गुजराती किताब छपेगी तो भाषा को सीखने में आने वाली आधी

दिक्कतें तो ऐसे ही कम हो जाएँगी।

- इस संस्करण को लोकप्रिय बनाने के लिए इसकी कीमत बहुत कम राखी

गयी है, मुझे उम्मीद है कि इस साहस को गुजराती और हिंदी पढ़ने वाले सफल

करेंगे।

इसी प्रकार विनोबा भावे का विचार था कि-

- हिन्दुस्तान की एकता के लिये हिन्दी भाषा

जितना काम देगी, उससे बहुत अधिक काम देवनागरी लिपि देगी। इसलिए मैं चाहता

हूँ कि सभी भाषाएँ देवनागरी में भी लिखी जाएं। सभी लिपियां चलें लेकिन

साथ-साथ देवनागरी का भी प्रयोग किया जाये। विनोबा जी “नागरी ही” नहीं

“नागरी भी” चाहते थे। उन्हीं की सद्प्रेरणा से 1975 में नागरी लिपि परिषद की स्थापना हुई।

विश्वलिपि के रूप में देवनागरी

बौद्ध संस्कृति से प्रभावित क्षेत्र नागरी के लिए नया नहीं है। चीन और जापान चित्रलिपि

का व्यवहार करते हैं। इन चित्रों की संख्या बहुत अधिक होने के कारण भाषा

सीखने में बहुत कठिनाई होती है। देववाणी की वाहिका होने के नाते देवनागरी

भारत की सीमाओं से बाहर निकलकर चीन और जापान के लिए भी समुचित विकल्प दे

सकती है। भारतीय मूल के लोग संसार में जहां-जहां भी रहते हैं, वे देवनागरी

से परिचय रखते हैं, विशेषकर मारीशस, सूरीनाम, फिजी, गुयाना, त्रिनिदाद, टोबैगो

आदि के लोग। इस तरह देवनागरी लिपि न केवल भारत के अंदर सारे प्रांतवासियों

को प्रेम-बंधन में बांधकर सीमोल्लंघन कर दक्षिण-पूर्व एशिया के पुराने

वृहत्तर भारतीय परिवार को भी ‘बहुजन हिताय, बहुजन सुखाय‘ अनुप्राणित कर

सकती है तथा विभिन्न देशों को एक अधिक सुचारू और वैज्ञानिक विकल्प प्रदान

कर ‘विश्व नागरी‘ की पदवी का दावा इक्कीसवीं सदी में कर सकती है। उस पर

प्रसार लिपिगत साम्राज्यवाद और शोषण का माध्यम न होकर सत्य, अहिंसा, त्याग,

संयम जैसे उदात्त मानवमूल्यों का संवाहक होगा, असत् से सत्, तमस् से

ज्योति तथा मृत्यु से अमरता की दिशा में।

लिपि-विहीन भाषाओं के लिये देवनागरी

दुनिया की कई भाषाओं के लिये देवनागरी सबसे अच्छा विकल्प हो सकती है

क्योंकि यह यह बोलने की पूरी आजादी देता है। दुनिया की और किसी भी लिपि मे

यह नही हो सकता है। इन्डोनेशिया, विएतनाम, अफ्रीका आदि के लिये तो यही सबसे

सही रहेगा। अष्टाध्यायी को देखकर कोई भी समझ सकता है की दुनिया मे इससे

अच्छी कोई भी लिपि नहीं है। अगर दुनिया पक्षपातरहित हो तो देवनागरी ही

दुनिया की सर्वमान्य लिपि होगी क्योंकि यह पूर्णत: वैज्ञानिक है। अंग्रेजी भाषा में वर्तनी (स्पेलिंग) की विकराल समस्या के कारगर समाधान के लिये देवनागरी पर आधारित देवग्रीक लिपि प्रस्तावित की गयी है।

देवनागरी की वैज्ञानिकता

विस्तृत लेख देवनागरी की वैज्ञानिकता देखें।

जिस प्रकार भारतीय अंकों

को उनकी वैज्ञानिकता के कारण विश्व ने सहर्ष स्वीकार कर लिया वैसे ही

देवनागरी भी अपनी वैज्ञानिकता के कारण ही एक दिन विश्वनागरी बनेगी।

देवनागरी लिपि में सुधार

देवनागरी का विकास उस युग में हुआ था जब लेखन हाथ से किया जाता था और लेखन के लिए शिलाएँ, ताड़पत्र, चर्मपत्र, भोजपत्र, ताम्रपत्र आदि का ही प्रयोग होता था। किन्तु लेखन प्रौद्योगिकी ने बहुत अधिक विकास किया और प्रिन्टिंग प्रेस, टाइपराइटर

आदि से होते हुए वह कम्प्यूटर युग में पहुँच गयी है जहाँ बोलकर भी लिखना

सम्भव हो गया है।

जब प्रिंटिंग एवं टाइपिंग का युग आया तो देवनागरी के यंत्रीकरण में कुछ

अतिरिक्त समस्याएँ सामने आयीं जो रोमन में नहीं थीं। उदाहरण के लिए रोमन

टाइपराइटर में अपेक्षाकृत कम कुंजियों की आवश्यकता पड़ती थी। देवनागरी में

संयुक्ताक्षर की अवधारणा होने से भी बहुत अधिक कुंजियों की आवश्यकता पड़

रही थी। ध्यातव्य है कि ये समस्याएँ केवल देवनागरी में नहीं थी बल्कि रोमन

और

सिरिलिक को छोड़कर लगभग सभी लिपियों में थी। चीनी और उस परिवार की अन्य

लिपियों में तो यह समस्या अपने गम्भीरतम रूप में थी।

इन सामयिक समस्याओं को ध्यान में रखते हुए अनेक विद्वानों और

मनीषियों ने देवनागरी के सरलीकरण और मानकीकरण पर विचार किया और अपने सुझाव

दिए। इनमें से अनेक सुझावों को क्रियान्वित नहीं किया जा सका या उन्हें

अस्वीकार कर दिया गया। कहने की आवश्यकता नहीं है कि कम्प्यूटर युग आने से

(या प्रिंटिंग की नई तकनीकी आने से) देवनागरी से सम्बन्धित सारी समस्याएँ

स्वयं समाप्त हों गयीं।

भारत के स्वाधीनता आंदोलनों में हिंदी को राष्ट्रभाषा का दर्जा प्राप्त होने के बाद लिपि के विकास व मानकीकरण हेतु कई व्यक्तिगत एवं संस्थागत प्रयास हुए। सर्वप्रथम बम्बई के महादेव गोविन्द रानडे ने एक लिपि सुधार समिति का गठन किया। तदन्तर महाराष्ट्र साहित्य परिषद पुणे ने सुधार योजना तैयार की। सन १९०४ में बाल गंगाधर तिलक ने अपने केसरी

पत्र में देवनागरी लिपि के सुधार की चर्चा की। प्रिणामस्वरूप देवनागरी के

टाइपों की संख्या १९० निर्धारित की गयी और इन्हें ‘केसरी टाइप’ कहा गया।[16]

आगे चलकर सावरकर बंधुओं ने ‘अ’ की बारहखड़ी प्रयिग करने का सुझाव दिया ( अर्थात ‘ई’ न लिखकर अ पर बड़ी ई की मात्रा लगायी जाय)। डॉ गोरख प्रसाद ने सुझाव दिया कि मात्राओं को व्यंजन के बाद दाहिने तरफ अलग से रखा जाय। डॉ. श्यामसुन्दर दास ने अनुस्वार

के प्रयोग को व्यापक बनाकर देवनागरी के सरलीकरण के प्रयास किये (पंचमाक्षर

के बदले अनुस्वार के प्रयोग )। इसी प्रकार श्रीनिवास का सुझाव था कि

महाप्राण वर्ण के लिए अल्पप्राण के नीचे ऽ चिह्न लगाया जाय। १९४५ में काशी नागरी प्रचारिणी सभा द्वारा अ की बारहखड़ी और श्रीनिवास के सुझाव को अस्वीकार करने का निर्णय लिया गया।[17]

देवनागरी के विकास में अनेक संस्थागत प्रयासों की भूमिका भी अत्यन्त महत्त्वपूर्ण रही है। १९३५ में हिंदी साहित्य सम्मेलन ने नागरी लिपि सुधार समिति[18] के माध्यम से ‘अ’ की बारहखड़ी और शिरोरेखा से संबंधित सुधार सुझाए। इसी प्रकार, १९४७ में आचार्य नरेन्द्र देव

की अध्यक्षता में गठित एक समिति ने बारहखड़ी, मात्रा व्यवस्था, अनुस्वार व

अनुनासिक से संबंधित महत्त्वपूर्ण सुझाव दिये। देवनागरी लिपि के विकास

हेतु भारत सरकार

के शिक्षा मंत्रालय ने कई स्तरों पर प्रयास किये हैं। सन् १९६६ में मानक

देवनागरी वर्णमाला प्रकाशित की गई और १९६७ में ‘हिंदी वर्तनी का मानकीकरण’

प्रकाशित किया गया। १९८३ में ‘देवनागरी लिपि तथा हिन्दी की वर्तनी का

मानकीकरण’ प्रकाशित किया गया।

देवनागरी के सम्पादित्र व अन्य सॉफ्टवेयर

इंटरनेट पर हिन्दी के साधन देखिये।

देवनागरी से अन्य लिपियों में रूपान्तरण

- ITRANS (iTrans) निरूपण, देवनागरी को लैटिन (रोमन) में परिवर्तित करने का आधुनिकतम और अक्षत (lossless) तरीका है। (Online Interface to iTrans)

- आजकल अनेक कम्प्यूटर प्रोग्राम उपलब्ध हैं जिनकी सहायता से देवनागरी में लिखे पाठ को किसी भी भारतीय लिपि में बदला जा सकता है। [19]

- कुछ ऐसे भी कम्प्यूटर प्रोग्राम हैं जिनकी सहायता से देवनागरी में

लिखे पाठ को लैटिन, अरबी, चीनी, क्रिलिक, आईपीए (IPA) आदि में बदला जा सकता

है। (ICU Transform Demo)

- यूनिकोड

के पदार्पण के बाद देवनागरी का रोमनीकरण (romanization) अब अनावश्यक होता

जा रहा है, क्योंकि धीरे-धीरे कम्प्यूटर, स्मार्ट फोन तथा अन्य डिजिटल

युक्तियों पर देवनागरी को (और अन्य लिपियों को भी) पूर्ण समर्थन मिलने लगा

है।

देवनागरी यूनिकोड

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F |

|

| U+090x |

ऀ | ँ | ं | ः | ऄ | अ | आ | इ | ई | उ | ऊ | ऋ | ऌ | ऍ | ऎ | ए |

| U+091x |

ऐ | ऑ | ऒ | ओ | औ | क | ख | ग | घ | ङ | च | छ | ज | झ | ञ | ट |

| U+092x |

ठ | ड | ढ | ण | त | थ | द | ध | न | ऩ | प | फ | ब | भ | म | य |

| U+093x |

र | ऱ | ल | ळ | ऴ | व | श | ष | स | ह | ऺ | ऻ | ़ | ऽ | ा | ि |

| U+094x |

ी | ु | ू | ृ | ॄ | ॅ | ॆ | े | ै | ॉ | ॊ | ो | ौ | ् | ॎ | ॏ |

| U+095x |

ॐ | ॑ | ॒ | ॓ | ॔ | ॕ | ॖ | ॗ | क़ | ख़ | ग़ | ज़ | ड़ | ढ़ | फ़ | य़ |

| U+096x |

ॠ | ॡ | ॢ | ॣ | । | ॥ | ० | १ | २ | ३ | ४ | ५ | ६ | ७ | ८ | ९ |

| U+097x |

॰ | ॱ | ॲ | ॳ | ॴ | ॵ | ॶ | ॷ | ॸ | ॹ | ॺ | ॻ | ॼ | ॽ | ॾ | ॿ |

संगणक कुंजीपटल पर देवनागरी

सन्दर्भ

gazett नाम के संदर्भ में जानकारी नहीं है।… In

the Kutila this develops into a short horizontal bar, which, in the

Devanagari, becomes a continuous horizontal line … three cardinal

inscriptions of this epoch, namely, the Kutila or Bareli inscription of

992, the Chalukya

or Kistna inscription of 945, and a Kawi inscription of 919 … the

Kutila inscription is of great importance in Indian epigraphy, not only

from its precise date, but from its offering a definite early form of

the standard Indian alphabet, the Devanagari …

(p.

110) “… an early branch of this, as of the fourth century CE, was the

Gupta script, Brahmi’s first main daughter. […] The Gupta alphabet

became the ancestor of most Indic scripts (usually through later

Devanagari). […] Beginning around AD 600, Gupta inspired the important

Nagari, Sarada, Tibetan and Pāḷi scripts. Nagari, of India’s northwest,

first appeared around AD 633. Once fully developed in the eleventh

century, Nagari had become Devanagari, or “heavenly Nagari”, since it

was now the main vehicle, out of several, for Sanskrit literature.”

at Google Books, Rudradaman’s inscription from 1st through 4th century

CE found in Gujarat, India, Stanford University Archives, pages 30–45,

particularly Devanagari inscription on Jayadaman’s coins pages 33–34

“(p. 110) “… an early branch of this, as of the fourth century CE,

was the Gupta script, Brahmi’s first main daughter. […] The Gupta

alphabet became the ancestor of most Indic scripts (usually through

later Devanagari). […] Beginning around AD 600, Gupta inspired the

important Nagari, Sarada, Tibetan and Pāḷi scripts. Nagari, of India’s

northwest, first appeared around AD 633. Once fully developed in the

eleventh century, Nagari had become Devanagari, or “heavenly Nagari”,

since it was now the main vehicle, out of several, for Sanskrit

literature.”"

- Ram Narayan Ray

इन्हें भी देखें

|

बाहरी कड़ियाँ

- ब्राह्मी-लिपि परिवार का वृक्ष - इसमें ब्राह्मी से उत्पन्न लिपियों की समय-रेखा का चित्र दिया हुआ है।

- पहलवी-ब्राह्मी लिपि से उत्पन्न दक्षिण-पूर्व एशिया की लिपियों की समय-रेखा

- राष्ट्रीय एकता की धरोहर : देवनागरी लिपि[मृत कड़ियाँ]

- सबने स्वीकारा है देवनागरी की वैज्ञानिकता को (प्रभासाक्षी)

- देवनागरी का लंबा विकासात्मक इतिहास (प्रभासाक्षी)

- राष्ट्रीय एकता की धरोहर : देवनागरी लिपि[मृत कड़ियाँ] (मधुमती)

- हर ढांचे में आसानी से ढल जाती है नागरी (डॉ॰ जुबैदा हाशिम मुल्ला ; 02 मई 2012)

- Unicode Entity Codes for the Devanāgarī Script

- https://web.archive.org/web/20030801223449/http://www.ancientscripts.com/devanagari.html

- https://web.archive.org/web/20140901145421/http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U0900.pdf

- Language Independent Speech Compression using Devanagari Phonetics

- राजभाषा हिन्दी (गूगल पुस्तक ; लेखक - भोलानाथ तिवारी)

- अंग्रेजी भी देवनागरी में लिखें

- Devanagari character picker v11

- The Influence of Sanskrit on the Japanese Sound System (James H. Buck, University of Georgia)

- देवनागरी सॉफ्टवेयर (केविन कार्मोदी)

- Sanskrit Lesson 3 – Sanskrit Alphabet and Devanagari Script

- देवनागरी लिपि एवं संगणक (अम्बा कुलकर्णी, विभागाध्यक्ष ,संस्कृत अध्ययन विभाग, हैदराबाद विश्वविद्यालय)

जागृति यूनिवर्स के साथ मेटेक्या जागृत की खोज (FOAINDMAOAU)

वर्तमान

स्थिति 04-8-2020 और 3-12-2020 के बीच समाप्त होती है, जो नि: शुल्क

ऑनलाइन विश्लेषणात्मक अंतर्दृष्टि नेट के लिए मार्ग प्रशस्त करती है

के लिये

कल्याण, खुशी, सभी संवेदी और गैर-सजातीय लोगों की शांति और उनके लिए अंतिम लक्ष्य के रूप में शाश्वत शांति प्राप्त करना।

से

कुशीनार निबाण भामि पगोडा

116 भाषा विज्ञान में

के माध्यम से

http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org

पर

सफेद घर

668, 5 ए मुख्य सड़क, 8 वीं क्रॉस, एचएएल III स्टेज,

प्रबुद्ध भारत पुण्यभूमि बेंगलुरु

मगधी कर्नाटक राज्य

प्रबुद्ध भाव

जागरूकता के साथ जागृति एक के साथ अच्छे सर्वेक्षण के मिनट और पर्यावरणविज्ञान को देखें

से

कुशीनारा निबाना भूमि पैगोडा के लिए 3 डी सर्कल-विज़न 360 ° में आभासी दौरे के चरण निर्माण द्वारा मुफ्त ऑनलाइन कदम

शास्त्रीय देवनागरी में महासतीपाठ्य सूत्र, शास्त्रीय हिंदी-देवनागरी- प्राथमिक हिंदी

ttps: //srv1.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

अंतिम अद्यतन: 30 जून, 2020, 02:33 GMT

कोरोनावाइरस के केस:

10,408,433

मौतें:

508,078

7,794,770,907

वर्तमान विश्व जनसंख्या -40,382,525 नेट जनसंख्या वृद्धि इस वर्ष- 79,241

नेट जनसंख्या वृद्धि आज 69,603,91 बर्थ इस वर्ष-136,581 बर्थ

आज-पुनर्प्राप्त: COVID-19 कोरोनवायरस वायरस महामारी से 6,664,407

सभी

खुश, अच्छी तरह से और सुरक्षित हो सकते हैं! सभी लंबे समय तक रह सकते हैं!

सभी को शांत, शांत, सतर्क, चौकस और समभाव वाला होना चाहिए। एक स्पष्ट समझ

के साथ कि सब कुछ बदल रहा है। romanalipyAH devanAgarIlipyAm parivartanam

सजगता के साथ मेटेय्या जागृत एक के शब्द

से

कुशीनारा निबाना भूमि पैगोडा के लिए 3 डी सर्कल-विज़न 360 ° में आभासी दौरे के चरण निर्माण द्वारा मुफ्त ऑनलाइन कदम

यह

रूपरेखा चैपनिम्हा साग th याना (छठी परिषद) टिपीफाका के देवान line

गारी-लिपि संस्करण में पुस्तकों के प्रकाशन को प्रदर्शित करती है। वॉल्यूम

के नामों को इटैलिक्स में प्रत्यय “-p ⁄ 1i4i” के साथ प्रदर्शित किया गया

है, यह संकेत करते हुए कि टिप्पणी टिपेरियल साहित्य के बजाय वॉल्यूम

टिपिफाका का हिस्सा है। यह रूपरेखा केवल रूट वॉल्यूम को सूचीबद्ध करती है।

कृपया ध्यान दें: ये पुस्तकें केवल P ± li में, Devan and gari स्क्रिप्ट

में हैं, और बिक्री के लिए नहीं हैं।

अंग्रेजी अनुवाद का कोई सेट उपलब्ध नहीं है। अधिक जानकारी के लिए कृपया देखें: www.tipitaka.org

(तीन किताबें, 5 किताबों में छपीं)

Sutta Vibhaaga [दो किताबें जिनमें भिक्खु और भिक्खुनिस के लिए नियम हैं, अपराध की आठ कक्षाओं को रेखांकित करती हैं]

टिपियापका (तीन “बास्केट”)

सुत्त पिरपका

(पांच निक Five यास, या संग्रह)

सुत्त

पिआका में धम्म के बारे में बुद्ध के शिक्षण का सार है। इसमें दस हज़ार से

अधिक सत्त शामिल हैं। इसे पाँच संग्रह में विभाजित किया जाता है जिसे

निकयास (एक भीड़, संयोजन; एक संग्रह; एक वर्ग, आदेश, समूह; एक संघ,

बंधुत्व, मण्डली; एक घर, आवास) कहा जाता है।

दीघा निकया [दीघा: लंबी]

बुद्ध

द्वारा दिए गए सबसे लंबे प्रवचनों में से दीघा निकाह 34 को इकट्ठा करता

है। विभिन्न संकेत हैं कि उनमें से कई मूल कॉर्पस और संदिग्ध प्रामाणिकता

के लिए देर से जोड़ रहे हैं।

मज्झिमा निकैया

[मज्झिमा: मध्यम] मज्झिमा निकाह विभिन्न मामलों से निपटने के लिए, मध्यवर्ती लंबाई के बुद्ध के 152 प्रवचनों को इकट्ठा करता है।

सौयुतता निकया

[samyutta:

group] सौयत्त निकेता अपने विषय के अनुसार ५६ उप समूहों में सौयत्त को

इकट्ठा करता है। इसमें परिवर्तनशील लंबाई के तीन हजार से अधिक प्रवचन होते

हैं, लेकिन आम तौर पर अपेक्षाकृत कम होते हैं।

अगुत्तारा निकया

[ag:

कारक | उत्तारा: इसके अलावा] अगुत्तारा निकाह को ग्यारह उप-समूहों में

उपनिषद कहा जाता है, उनमें से प्रत्येक सभा में एक अतिरिक्त कारक बनाम

उनमें से एक की गणना से जुड़े प्रवचन मिलते हैं।

पूर्ववर्ती निपटा। इसमें हजारों सत्त शामिल हैं जो आमतौर पर कम होते हैं।

खुदाका निकया

[khuddha:

short, small] खड्ढाका निकेया लघु ग्रंथ और माना जाता है कि यह दो स्तरों

से बना है: धम्मपद, उधना, इतिवत्तक, सुत्त निपात, थेरगथ-थिराघ्त और जातक

प्राचीन ग्रंथ हैं, जबकि अन्य पुस्तकें देर से प्रमाणित होती हैं। अधिक

संदिग्ध है।

सुत्त पिरपका

(पांच निक as यास, या संग्रह)

1. D2gha-nik [ya [34 suttas; 3 योनि, या अध्याय (प्रत्येक पुस्तक)]

(1) S2lakkhandavagga-p ⁄ 1i4i (13 suttas)

(२) महा ga योनि-पी) १i४ आई (१० सूत्त)

(३) पी ik μikavagga-p ⁄ १i४i (११ सुत्त)

2. मज्झिमा-निक [य [१५२ सत्त; १५ योनि; 3 पुस्तकों में विभाजित,

5 योनि प्रत्येक, जिसे ± सा () पचास ’) के रूप में जाना जाता है]

(1) M3lapaoo) ssa-p ⁄ 1i4i (’रूट’ पचास)

1. M3lapariy av यावग्गा (10 सुत्त)

2. S2han ± दवग्गा (10 सुत्त)

3. टटियावग्गा (10 सूत्त)

4. मह utt यामाकवग्गा (10 सुत्त)

5. सी 31 s4 श्यामकवग्गा (10 सुत्त)

(२) मज्झिमपाओ) सा-पी ⁄ १i४ आई (’मध्य’ पचास)

6. गपपति-योनि (10 सूक्त)

7. भिक्खु-योनि (10 सुत्त)

8. परब ± जाका-योनि (10 सुत्त)

9. आर as जा-योनि (10 सुत्त)

10. ब्राह्मण-योनि (10 सूत्त)

(३) उपरिप्पू) सा-पी ⁄ १i४ आई (मतलब ’पचास से अधिक’)

11. देवदाह-योनि (10 सूत्त)

12. अनुपदा-योनि (10 सूत्त)

13. सुन्नत-योनि (10 सूत्त)

14. विभागा-योनि (12 सूत्त)

15. Sa1ga4 ± यतना-योनि (10 सूत्त)

from COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic

Words of the Metteyya Awakened One with Awareness

from

Free Online step by step creation of Virtual tour in 3D Circle-Vision 360° for Kushinara Nibbana Bhumi Pagoda

This

outline displays the publication of books in the Devan±gari-script

edition of the Chaμμha Saag±yana (Sixth Council) Tipiμaka. The names of

the volumes are displayed in italics with the suffix “-p±1⁄4i”

indicating the volume is part of the root Tipiμaka, rather than

commentarial literature. This outline lists the root volumes only.Please

note: These books are in P±li only, in Devan±gari script, and are not

for sale.

No set of English translations is available. For further information please see: www.tipitaka.org

(Three divisions, printed in 5 books)

Sutta Vibhaaga [two books containing rules for the bhikkhus and bhikkhunis, outlining eight classes of offences]

Tipiμaka (three “baskets”)

Sutta Piμaka

(Five nik±yas, or collections)

The Sutta Piṭaka contains the essence of the Buddha’s teaching

regarding the Dhamma. It contains more than ten thousand suttas. It is

divided in five collections called Nikāyas (A multitude, assemblage; a

collection; a class, order, group; an association, fraternity,

congregation; a house, dwelling).

Dīgha Nikāya[dīgha: long] The

Dīgha Nikāya gathers 34 of the longest discourses given by the Buddha.

There are various hints that many of them are late additions to the

original corpus and of questionable authenticity.

Majjhima Nikāya

[majjhima:

medium] The Majjhima Nikāya gathers 152 discourses of the Buddha of

intermediate length, dealing with diverse matters.

Saṃyutta Nikāya

[samyutta:

group] The Saṃyutta Nikāya gathers the suttas according to their

subject in 56 sub-groups called saṃyuttas. It contains more than three

thousand discourses of variable length, but generally relatively short.

Aṅguttara Nikāya

[aṅg:

factor | uttara: additionnal] The Aṅguttara Nikāya is subdivized in

eleven sub-groups called nipātas, each of them gathering discourses

consisting of enumerations of one additional factor versus those of the

precedent nipāta. It contains thousands of suttas which are generally short.

Khuddaka Nikāya

[khuddha:

short, small] The Khuddhaka Nikāya short texts and is considered as

been composed of two stratas: Dhammapada, Udāna, Itivuttaka, Sutta

Nipāta, Theragāthā-Therīgāthā and Jātaka form the ancient strata, while

other books are late additions and their authenticity is more

questionable.

Sutta Piμaka

(Five nik±yas, or collections)

1. D2gha-nik±ya [34 suttas; 3 vaggas, or chapters (each a book)]

(1) S2lakkhandavagga-p±1⁄4i (13 suttas)

(2) Mah±vagga-p±1⁄4i (10 suttas)

(3) P±μikavagga-p±1⁄4i (11 suttas)

2. Majjhima-nik±ya [152 suttas;15 vaggas; divided in 3 books,

5 vaggas each, known as paoo±sa (‘fifty’)]

(1) M3lapaoo±ssa-p±1⁄4i (the ‘root’ fifty)

1. M3lapariy±yavagga (10 suttas)

2. S2han±davagga (10 suttas)

3. Tatiyavagga (10 suttas)

4. Mah±yamakavagga (10 suttas)

5. C31⁄4ayamakavagga (10 suttas)

(2) Majjhimapaoo±sa-p±1⁄4i (the ‘middle’ fifty)

6. Gahapati-vagga (10 suttas)

7. Bhikkhu-vagga (10 suttas)

8. Paribb±jaka-vagga (10 suttas)

9. R±ja-vagga (10 suttas)

10. Br±hmana-vagga (10 suttas)

(3) Uparipaoo±sa-p±1⁄4i (means ‘more than fifty’)

11. Devadaha-vagga (10 suttas)

12. Anupada-vagga (10 suttas)

13. Suññata-vagga (10 suttas)

14. Vibhaaga-vagga (12 suttas)

15. Sa1⁄4±yatana-vagga (10 suttas)

3. Sa1⁄2yutta-nik±ya [2,904 (7,762) suttas; 56 sa1⁄2yuttas; 5 vaggas; divided

into 6 books]

(1) Sag±thavagga-sa1⁄2yutta-p±1⁄4i (11 sa1⁄2yuttas)

(2) Nid±navagga-sa1⁄2yutta-p±1⁄4i (10 sa1⁄2yuttas)

(3) Khandavagga-sa1⁄2yutta-p±1⁄4i (13 sa1⁄2yuttas)

(4) Sa1⁄4±yatanavagga-sa1⁄2yutta-p±1⁄4i (10 sa1⁄2yuttas)

(5) Mah±vagga-sa1⁄2yutta-p±1⁄4i Vol I ( 6 sa1⁄2yuttas)

(6) Mah±vagga-sa1⁄2yutta-p±1⁄4i Vol II ( 6 sa1⁄2yuttas)

4. Aaguttara-nik±ya [9,557 suttas; in11 nip±tas, or groups, arranged purely

numerically; each nip±ta has several vaggas; 10 or more suttas in

each vagga; 6 books]

(1) Eka-Duka-Tika-nipata-p±1⁄4i (ones, twos, threes)

(2) Catukka-nipata-p±1⁄4i (fours)

(3) Pañcaka-nipata-p±1⁄4i (fives)

(4) Chakka-Sattaka-nipata-p±1⁄4i (sixes, sevens)

(5) Aμμhaka-Navaka-nipata-p±1⁄4i (eights, nines)

(6) Dasaka-Ekadasaka-nipata-p±1⁄4i (tens, elevens)

5. Khuddaka-nik±ya [the collection of small books, a miscellaneous gather-

ing of works in 18 main sections; it includes suttas, compilations of

doctrinal notes, histories, verses, and commentarial literature that has

been incorporated into the Tipiμaka itself.; 12 books]

(1) Kuddhakap±tha,Dhammapada & Ud±na-p±1⁄4i

1. Kuddhakap±tha (nine short formulae and suttas, used as a training manual for

novice bhikkhus)

2. Dhammapada (most famous of all the books of the Tipiμaka; a collection of 423

verses in 26 vaggas)

3. Ud±na (in 8 vaggas, 80 joyful utterances of the Buddha, mostly in verses, with

some prose accounts of the circumstances that elicited the utterance)

(2) Itivuttaka, Suttanip±ta-p±1⁄4i

4. Itivuttaka (4 nip±tas, 112 suttas, each beginning, “iti vutta1⁄2 bhagavata” [thus was

said by the Buddha])

5. Suttanip±ta (5 vaggas; 71 suttas, mostly in verse; contains many of the best

known, most popular suttas of the Buddha

(3) Vim±navatthu, Petavatthu, Therag±th± & Therig±th±-p±1⁄4i

6. Vim±navatthu (Vim±na means mansion; 85 poems in 7 vaggas about acts of

merit and rebirth in heavenly realms)

7. Petavatthu (4 vaggas, 51 poems describing the miserable beings [petas] born in

unhappy states due to their demeritorious acts)

8. Therag±th± (verses of joy and delight after the attainment of arahatship from 264

elder bhikkhus; 107 poems, 1,279 g±thas)

9. Therig±th± (same as above, from 73 elder nuns; 73 poems, 522 g±thas)

(4) J±taka-p±1⁄4i, Vol. I

(5) J±taka-p±1⁄4i, Vol II

10. J±taka (birth stories of the Bodisatta prior to his birth as Gotama Buddha; 547

stories in verses, divided into nip±ta according to the number of verses required to

tell the story. The full J±taka stories are actually in the J±taka commentaries that

explain the story behind the verses.

(6) Mah±nidessa-p±1⁄4i

(7) C31⁄4anidessa-p±1⁄4i

11. Nidessa (commentary on two sections of Suttanip±ta)

Mah±nidessa: commentary on the 4th vagga

C31⁄4anidessa: commentary on the 5th vagga and

the Khaggavis±oa sutta of the 1st vagga

(8) Paμisambhid±magga-p±1⁄4i

12. Paμisambhid±magga (an abhidhamma-style detailed analysis of the Buddha’s

teaching, drawn from all portions of the Vin±ya and Sutta Piμakas; three vaggas,

each containing ten topics [kath±])

(9) Apad±na-p±1⁄4i, Vol. I

13. Apad±na (tales in verses of the former lives of 550 bhikkhus and 40 bhikkhunis)

(10) Apad±na, Buddhava1⁄2sa & Cariy±piμaka-p±1⁄4i

14. Buddhava1⁄2sa (the history of the Buddhas in which the Buddha, in answer to a

question from Ven. Sariputta, tells the story of the ascetic Sumedha and D2paakara

Buddha and the succeeding 24 Buddhas, including Gotama Buddha.)

15. Cariy±piμaka (35 stories from the J±taka arranged to illustrate the ten p±ram2)

(11) Nettippakarana, Peμakopadesa-p±1⁄4i

16. Nettippakarana (small treatise setting out methods for interpreting and explain-

ing canonical texts)

17. Peμakopadesa (treatise setting out methods for explaining and expanding the

teaching of the Buddha)

(12) Milindapañha-p±1⁄4i

18. Milinda-pañha (a record of the questions posed by King Milinda and the

answers by Ven. Nagasena; this debate took place ca. 500 years after the

mah±parinibb±na of the Buddha)

Abhidhamma Piμaka

[Seven sections of systematic, abstract exposition of all dhammas; printed in

12 books]

1. Dhammasaagao2

(enumeration of the dhammas)

(1) Dhammasaagao2-p±1⁄4i

2. Vibhaaga-p±1⁄42

(distinction or analysis of dhammas)

(2) Vibhaaga-p±1⁄42

3. Dh±tukath±

(discussion of elements; these 1st three sections form a trilogy that

must be digested as a basis for understanding Abhidhamma)

4. Puggalapaññatti

(designation of individuals; ten chapters: the 1st dealing with single

individuals, the 2nd with pairs, the 3rd with groups of three, etc.

(3) Dh±tukath±-Puggalapaññatti-p±1⁄42

5. Kath±vatthu-p±1⁄42

(points of controversy or wrong view; discusses the points raised and

settled at the 3rd council, held at the time of Aœoka’s reign, at Patna)

(4) Kath±vatthu-p±1⁄42

6. Yamaka-p±1⁄42

(book of pairs; a use of paired, opposing questions to resolve ambi-

guities and define precise usage of technical terms)

(5) Yamaka-p±1⁄42, Vol I

(6) Yamaka-p±1⁄42, Vol II

(7) Yamaka-p±1⁄42, Vol III

7. Paμμh±na

(book of relations; the elaboration of a scheme of 24 conditional

relations [paccaya] that forms a complete system for understanding

the mechanics of the entire universe of Dhamma)

(8) Paμμh±na-p±1⁄4i, Vol I

(9) Paμμh±na-p±1⁄4i, Vol II

(10) Paμμh±na-p±1⁄4i, Vol III

(11) Paμμh±na-p±1⁄4i, Vol IV

(12) Paμμh±na-p±1⁄4i, Vol V

(1) P±r±jika-p±1⁄4i Bhikku

p±r±jik± (expulsion) 4

saaghadises± (meetings of the Sangha) 13

aniyat± (indeterminate) 2

nissagiy± p±cittiy± (expiation with forfeiture) 30

(2) P±cittiya-p±1⁄4i

suddha p±cittiy± (ordinary expiation) 92

p±tidesaniy± (confession re: alms food) 4

sekhiya (concerning etiquette & decorum) 75

adhikaraoasamath± (legal process) 7

(concludes with bhikkuni vinaya rules) ______Bhikkhuni

2. Khandaka [two books of rules and procedures]

(3) Mah±vagga-p±1⁄4i (10 sections [khandhakas]; begins with historical accounts of the

Buddha’s enlightenment, the first discourses and the early growth of the Sangha;

outlines the following rules governing the actions of the Sangha:

1. rules for admission to the order (upasampad±)

2. the uposatha meeting and recital of the p±timokkha

3. residence during the rainy season (vassa)

4. ceremony concluding the vassa, called pav±rao±

5. rules for articles of dress and furniture

6. medicine and food

7. annual distribution of robes (kaμhina)

8. rules for sick bhikkhus, sleeping and robe material

9. mode of executing proceedings of the Sangha

10. proceedings in cases of schism

(4) C31⁄4avagga-p±1⁄4i (or Cullavagga) (12 khandakas dealing with further rules and proce-

dures for institutional acts or functions, known as saaghakamma:

1. rules for dealing with offences that come before the Sangha

(saagh±disesa)

2. procedures for putting a bhikkhu on probation

3. procedures for dealing with accumulation of offences by a bhikkhu

4. rules for settling legal procedures in the Sangha

5. misc. rules for bathing, dress, etc.

6. dwellings, furniture, lodging, etc.

7. schisms

8. classes of bhikkhus and duties of teachers & novices

9. exclusion from the p±timokkha

10. the ordination and instruction of bhikkhunis

11. account of the 1st council at R±jagaha

12. account of the 2nd council at Ves±li

3. Pariv±ra-p±1⁄4i [a summary of the vinaya, arranged as a

catechism for instruction and examination]

(5) Pariv±ra-p±1⁄4i The fifth book of vinaya serves as a kind of manual enabling the reader

to make an analytical survey of the whole of Vinaya Piμaka.

Sutta Piṭaka -Digha Nikāya DN 9 -

Poṭṭhapāda Sutta

{excerpt}

— The questions of Poṭṭhapāda — Poṭṭhapāda asks various questions reagrding the nature of Saññā. Note: plain texts

Now,

lord, does perception arise first, and knowledge after; or does

knowledge arise first, and perception after; or do perception &

knowledge arise simultaneously?

Potthapada, perception arises

first, and knowledge after. And the arising of knowledge comes from the

arising of perception. One discerns, ‘It’s in dependence on this that my

knowledgehas arisen.’ Through this line of reasoning one can realize

how perception arises first, and knowledge after, and how the arising of

knowledge comes from the arising of perception.DN 22 - (D ii 290)

Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Sutta

— Attendance on awareness —

[

mahā+satipaṭṭhāna ] This sutta is widely considered as a the main

reference for meditation practice. Note: infobubbles on all Pali words

English Introduction I. Observation of Kāya

A. Section on ānāpāna

B. Section on postures

C. Section on sampajañña

D. Section on repulsiveness

E. Section on the Elements

F. Section on the nine charnel grounds

II. Observation of Vedanā

Introduction

Thus have I heard:

On

one occasion, the Bhagavā was staying among the Kurus at

Kammāsadhamma,a market town of the Kurus. There, he addressed the

bhikkhus:

– Bhikkhus.

– Bhaddante answered the bhikkhus. The Bhagavā said:

–

This, bhikkhus, is the path that leads to nothing but the purification

of beings, the overcoming of sorrow and lamentation, the disappearance

of dukkha-domanassa, the attainment of the right way, the realization of

Nibbāna, that is to say the four satipaṭṭhānas.

Which four?

Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu dwells observing kāya in kāya, ātāpī

sampajāno, satimā, having given up abhijjhā-domanassa towards the world

He dwells observing vedanā in vedanā, ātāpī sampajāno, satimā, having

given up abhijjhā-domanassa towards the world. He dwells observing citta

in citta, ātāpī sampajāno, satimā, having given up abhijjhā-domanassa

towards the world. He dwells observing dhamma·s in dhamma·s, ātāpī

sampajāno, satimā, having given up abhijjhā-domanassa towards the world.

I. Kāyānupassanā

A. Section on ānāpāna

And

how, bhikkhus, does a bhikkhu dwell observing kāya in kāya? Here,

bhikkhus, a bhikkhu, having gone to the forest or having gone at the

root of a tree or having gone to an empty room, sits down folding the

legs crosswise, setting kāya upright, and setting sati parimukhaṃ. Being

thus sato he breathes in, being thus sato he breathes out. Breathing in

long he understands: ‘I am breathing in long’; breathing out long he

understands: ‘I am breathing out long’; breathing in short he

understands: ‘I am breathing in short’; breathing out short he

understands: ‘I am breathing out short’; he trains himself: ‘feeling the

whole kāya, I will breathe in’; he trains himself: ‘feeling the whole

kāya, I will breathe out’; he trains himself: ‘calming down the

kāya-saṅkhāras, I will breathe in’; he trains himself: ‘calming down the

kāya-saṅkhāras, I will breathe out’.

Just as, bhikkhus, a

skillful turner or a turner’s apprentice, making a long turn,

understands: ‘I am making a long turn’; making a short turn, he

understands: ‘I am making a short turn’; in the same way, bhikkhus, a

bhikkhu, breathing in long, understands: ‘I am breathing in long’;

breathing out long he understands: ‘I am breathing out long’; breathing

in short he understands: ‘I am breathing in short’; breathing out short

he understands: ‘I am breathing out short’; he trains himself: ‘feeling

the whole kāya, I will breathe in’; he trains himself: ‘feeling the

whole kāya, I will breathe out’; he trains himself: ‘calming down the

kāya-saṅkhāras, I will breathe in’; he trains himself: ‘calming down the

kāya-saṅkhāras, I will breathe out’.

Thus he dwells observing

kāya in kāya internally, or he dwells observing kāya in kāya externally,

or he dwells observing kāya in kāya internally and externally; he

dwells observing the samudaya of phenomena in kāya, or he dwells

observing the passing away of phenomena in kāya, or he dwells observing

the samudaya and passing away of phenomena in kāya; or else,

[realizing:] “this is kāya!” sati is present in him, just to the extent

of mere ñāṇa and mere paṭissati, he dwells detached, and does not cling

to anything in the world. Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu dwells observing

kāya in kāya.

B. Section on postures

Furthermore,

bhikkhus, a bhikkhu, while walking, understands: ‘I am walking’, or

while standing he understands: ‘I am standing’, or while sitting he

understands: ‘I am sitting’, or while lying down he understands: ‘I am

lying down’. Or else, in whichever position his kāya is disposed, he

understands it accordingly.

Thus he dwells observing kāya in

kāya internally, or he dwells observing kāya in kāya externally, or he

dwells observing kāya in kāya internally and externally; he dwells

observing the samudaya of phenomena in kāya, or he dwells observing the

passing away of phenomena in kāya, or he dwells observing the samudaya

and passing away of phenomena in kāya; or else, [realizing:] “this is

kāya!” sati is present in him, just to the extent of mere ñāṇa and mere

paṭissati, he dwells detached, and does not cling to anything in the

world. Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu dwells observing kāya in kāya.

Thus he

dwells observing kāya in kāya internally, or he dwells observing kāya

in kāya externally, or he dwells observing kāya in kāya internally and

externally; he dwells observing the samudaya of phenomena in kāya, or he

dwells observing the passing away of phenomena in kāya, or he dwells

observing the samudaya and passing away of phenomena in kāya; or else,

[realizing:] “this is kāya!” sati is present in him, just to the extent

of mere ñāṇa and mere paṭissati, he dwells detached, and does not cling

to anything in the world. Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu dwells observing

kāya in kāya.

C. Section on sampajañña

Furthermore,

bhikkhus, a bhikkhu, while approaching and while departing, acts with

sampajañña, while looking ahead and while looking around, he acts with

sampajañña, while bending and while stretching, he acts with sampajañña,

while wearing the robes and the upper robe and while carrying the bowl,

he acts with sampajañña, while eating, while drinking, while chewing,

while tasting, he acts with sampajañña, while attending to the business

of defecating and urinating, he acts with sampajañña, while walking,

while standing, while sitting, while sleeping, while being awake, while

talking and while being silent, he acts with sampajañña.

Thus

he dwells observing kāya in kāya internally, or he dwells observing

kāya in kāya externally, or he dwells observing kāya in kāya internally

and externally; he dwells observing the samudaya o phenomena in kāya, or

he dwells observing the passing away of phenomena\ in kāya, or he

dwells observing the samudaya and passing away of phenomena in kāya; or

else, [realizing:] “this is kāya!” sati is present in him, just to the

extent of mere ñāṇa and mere paṭissati, he dwells detached, and does not

cling to anything in the world. Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu dwells

observing kāya in kāya.

D. Section on Repulsiveness

Furthermore,bhikkhus,

a bhikkhu considers this very body, from the soles of the feet up and

from the hair on the head down, which is delimited by its skin and full

of various kinds of impurities: “In this kāya, there are the hairs of

the head, hairs of the body, nails, teeth, skin, flesh, tendons, bones,

bone marrow, kidneys, heart, liver, pleura, spleen, lungs, intestines,

mesentery, stomach with its contents, feces, bile, phlegm, pus, blood,

sweat, fat, tears, grease, saliva, nasal mucus, synovial fluid and

urine.”

Just as if, bhikkhus, there was a bag having two

openings and filled with various kinds of grain, such as hill-paddy,

paddy, mung beans, cow-peas, sesame seeds and husked rice. A man with

good eyesight, having unfastened it, would consider [its contents]:

“This is hill-paddy, this is paddy, those are mung beans, those are

cow-peas, those are sesame seeds and this is husked rice;” in the same

way, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu considers this very body, from the soles of the

feet up and from the hair on the head down, which is delimited by its

skin and full of various kinds of impurities: “In this kāya, there are

the hairs of the head, hairs of the body, nails, teeth, skin, flesh,

tendons, bones, bone marrow, kidneys, heart, liver, pleura, spleen,

lungs, intestines, mesentery, stomach with its contents, feces, bile,

phlegm, pus, blood, sweat, fat, tears, grease,

saliva, nasal mucus, synovial fluid and urine.”

Thus

he dwells observing kāya in kāya internally, or he dwells observing

kāya in kāya externally, or he dwells observing kāya in kāya internally

and externally; he dwells observing the samudaya of phenomena in kāya,

or he dwells observing the passing away of phenomena in kāya, or he

dwells observing the samudaya and passing away of phenomena in kāya; or

else, [realizing:] “this is kāya!” sati is present in him, just to the

extent of mere ñāṇa and mere paṭissati, he dwells detached, and does not

cling to anything in the world. Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu dwells

observing kāya in kāya.

E. Section on the Elements

Furthermore,

bhikkhus, a bhikkhu reflects on this very kāya, however it is placed,

however it is disposed: “In this kāya, there is the earth element, the

water element, the fire element and the air element.”

Just as,

bhikkhus, a skillful butcher or a butcher’s apprentice, having killed a

cow, would sit at a crossroads cutting it into pieces; in the same way,

bhikkhus, a bhikkhu reflects on this very kāya, however it is placed,

however it is disposed: “In this kāya, there is the earth element, the

water element, the fire element and the air element.”

Thus he

dwells observing kāya in kāya internally, or he dwells observing kāya in

kāya externally, or he dwells observing kāya in kāya internally and

externally; he dwells observing the samudaya of phenomena in kāya, or he

dwells observing the passing away of phenomena in kāya, or he dwells

observing the samudaya and passing away of phenomena in kāya; or else,

[realizing:] “this is kāya!” sati is present in him, just to the extent

of mere ñāṇa and mere paṭissati, he dwells detached, and does not cling

to anything in the world. Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu dwells observing

kāya in kāya.

F. Section on the nine charnel grounds

(1)

Furthermore,

bhikkhus, a bhikkhu, just as if he was seeing a dead body, cast away in

a charnel ground, one day dead, or two days dead or three days dead,

swollen, bluish and festering, he considers this very kāya: “This kāya

also is of such a nature, it is going to become like this, and is not

free from such a condition.”

Thus he dwells observing kāya in

kāya internally, or he dwells observing kāya in kāya externally, or he

dwells observing kāya in kāya internally and externally; he dwells

observing the samudaya of phenomena in kāya, or he dwells observing the

passing away of phenomena in kāya, or he dwells observing the samudaya

and passing away of phenomena in kāya; or else, [realizing:] “this is

kāya!”\ sati is present in him, just to the extent of mere ñāṇa and mere

paṭissati, he dwells detached, and does not cling to anything in the

world. Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu dwells observing kāya in kāya.

(2)

Furthermore,

bhikkhus, a bhikkhu, just as if he was seeing a dead body, cast away in

a charnel ground, being eaten by crows, being eaten by hawks, being

eaten by vultures, being eaten by herons, being eaten by dogs, being

eaten by tigers, being eaten by panthers, being eaten by various kinds

of beings, he considers this very kāya: “This kāya also is of such a

nature, it is going to become like this, and is not free from such a

condition.

Thus he dwells observing kāya in kāya internally, or

he dwells observing kāya in kāya externally, or he dwells observing kāya

in kāya internally and externally; he dwells observing the samudaya of

phenomena in kāya, or he dwells observing the passing away of phenomena

in kāya, or he dwells observing the samudaya and passing away of

phenomena in kāya; or else, [realizing:] “this is kāya!” sati is present

in him, just to the extent of mere ñāṇa and mere paṭissati, he dwells

detached, and does not cling to anything in the world. Thus, bhikkhus, a

bhikkhu dwells observing kāya in kāya.

(3)

Furthermore,

bhikkhus, a bhikkhu, just as if he was seeing a dead body, cast away in a

charnel ground, a squeleton with flesh and blood, held together by

tendons, he considers this very kāya: “This kāya also is of such a

nature, it is going to become like this, and is not free from such a

condition.”

Thus he dwells observing kāya in kāya

internally, or he dwells observing kāya in kāya externally, or he dwells

observing kāya in kāya internally and externally; he dwells observing

the samudaya of phenomena in kāya, or he dwells observing the passing

away of phenomena in kāya, or he dwells observing the samudaya and

passing away of phenomena in kāya; or else, [realizing:] “this is kāya!”

sati is present in him, just to the extent of mere ñāṇa and mere

paṭissati, he dwells detached, and does not cling to anything in the

world. Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu dwells observing kāya in kāya.

(4)

Furthermore,

bhikkhus, a bhikkhu, just as if he was seeing a dead body, cast away in

acharnel ground, a squeleton without flesh and smeared with blood,

heldtogether by tendons, he considers this very kāya: “This kāya also is

of such a nature, it is going to become like this, and is not free from

such a condition.”

Thus he dwells observing kāya in kāya

internally, or he dwells observing kāya in kāya externally, or he dwells

observing kāya in kāya internally and externally; he dwells observing

the samudaya of phenomena in kāya, or he dwells observing the passing

away of phenomena in kāya, or he dwells observing the samudaya and

passing away of phenomena in kāya; or else, [realizing:] “this is kāya!”

sati is present in him, just to the extent of mere ñāṇa and mere

paṭissati, he dwells detached, and does not cling to anything in the

world. Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu dwells observing kāya in kāya.

(5)

Furthermore,

bhikkhus, a bhikkhu, just as if he was seeing a dead body, cast away in

a charnel ground, a squeleton without flesh nor blood, held together by

tendons, he considers this very kāya: “This kāya also is of such a

nature, it is going to become like this, and is not free from such a

condition.”

Thus he dwells observing kāya in kāya internally,

or he dwells observing kāya in kāya externally, or he dwells observing

kāya in kāya internally and externally; he dwells observing the samudaya