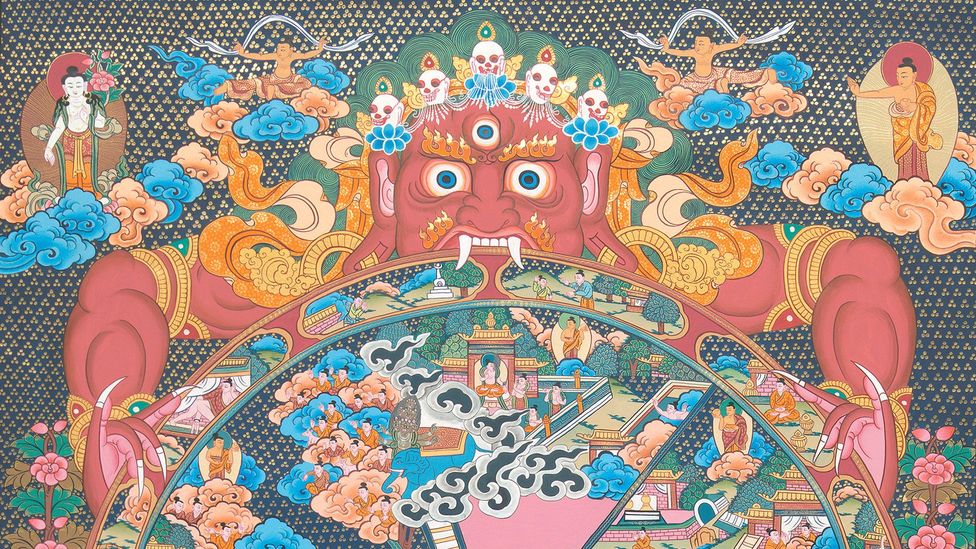

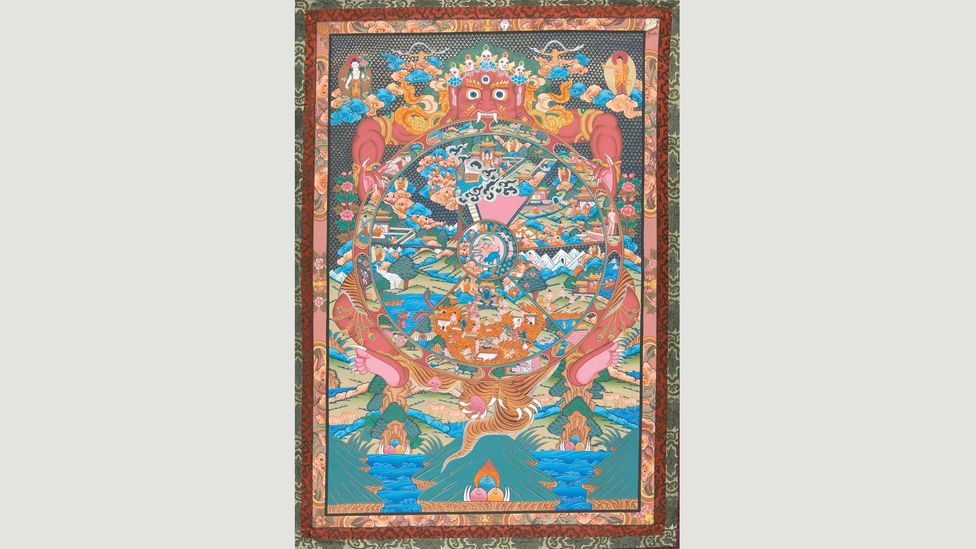

Do

you ever feel like you’re trapped in a hamster wheel, while the lord of

hell sinks his tusk-sized fangs into you? If so, you might feel a jolt

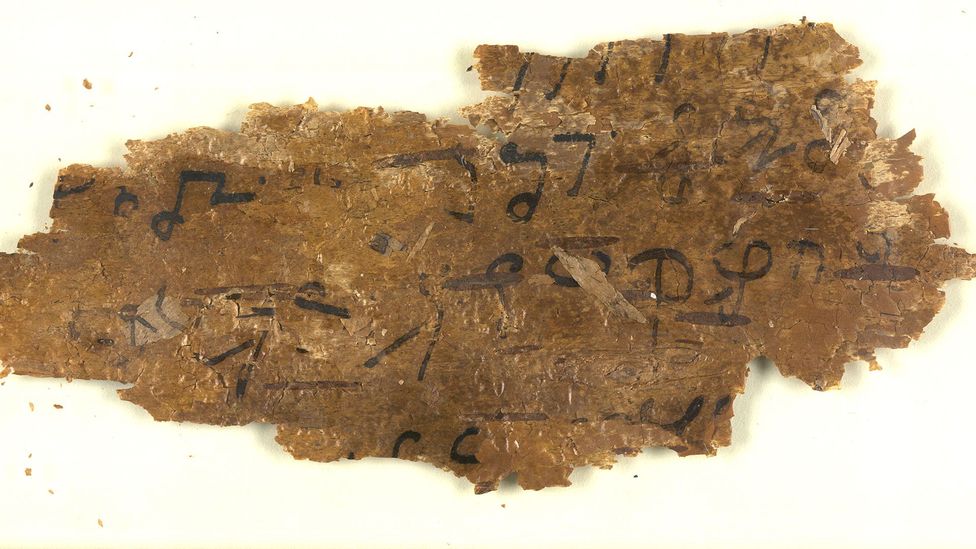

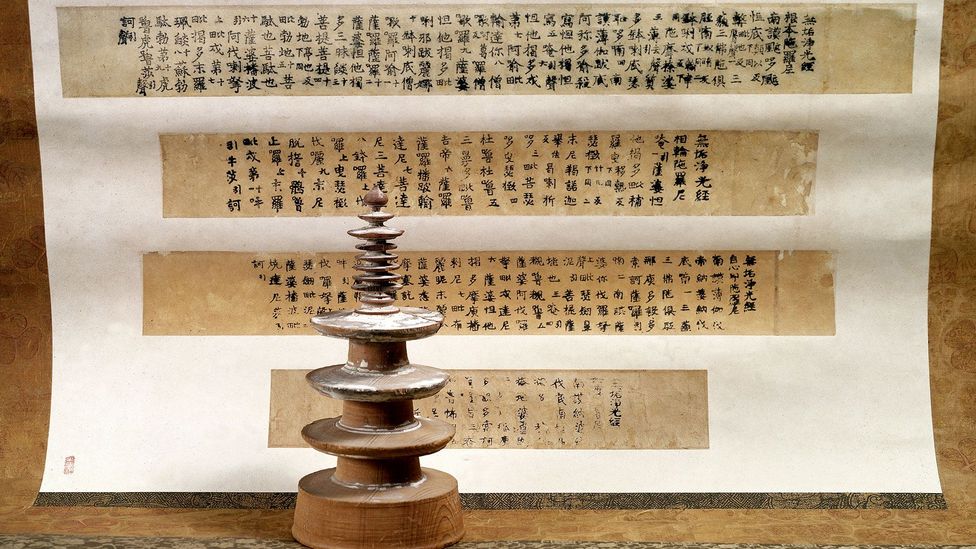

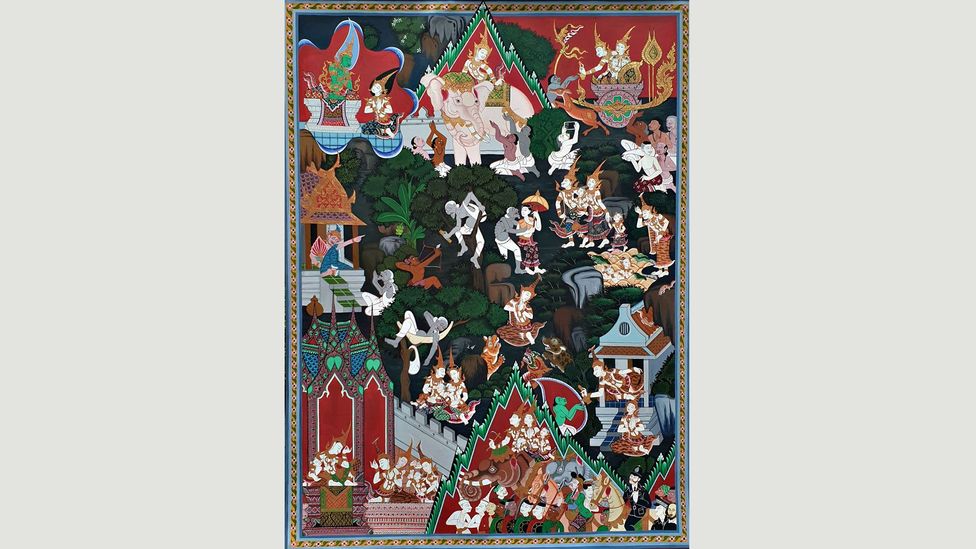

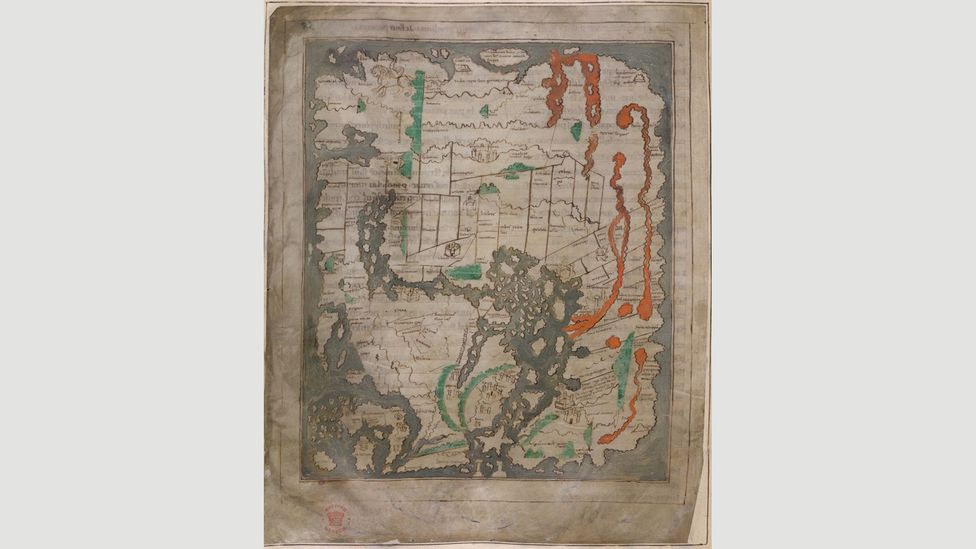

of recognition upon seeing a Buddhist thangka painting by the Nepalese Master Buddha Lama. It’s been created for an exhibition of Buddhist artworks and manuscripts now at the British Library in London, featuring scrolls, artefacts and illuminated books spanning 2,000 years and 20 countries.

More like this:

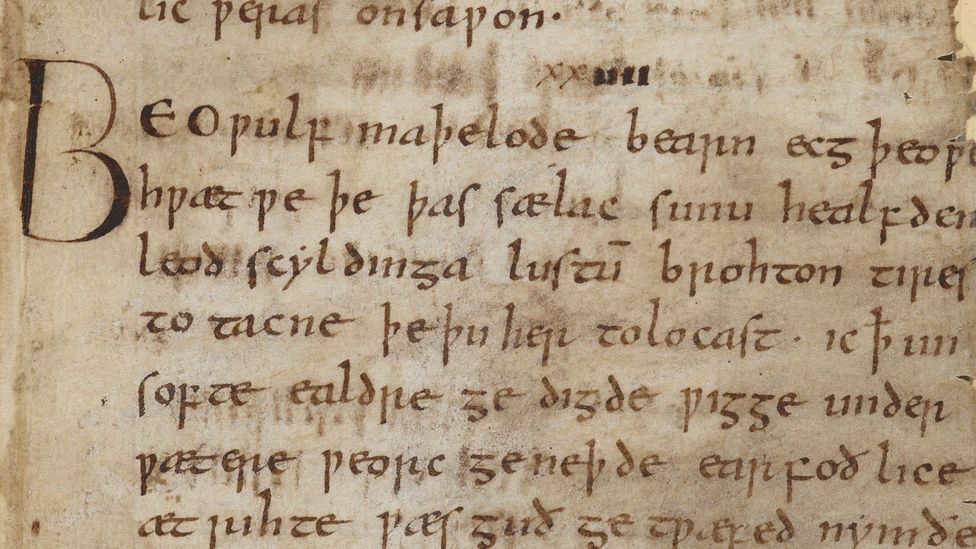

- The most powerful word in English

- The story of handwriting in 12 objects

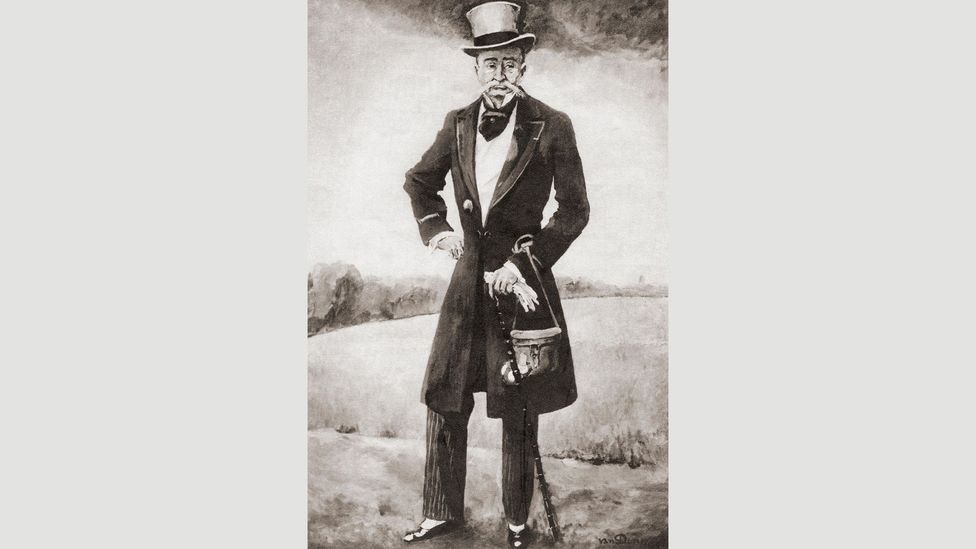

- The surprising history of the word ‘dude’

Although

Buddhist principles like mindfulness have filtered into mainstream

Western culture, other key tenets might not be as well-known. According

to Buddhist cosmology, life is suffering experienced within the cycle of

birth, death and rebirth. In Lama’s painting, we are in the big wheel

that Yama, the lord of hell, is holding. (His facial hair is on fire and

he wears a crown of skulls.) At the centre of the wheel are three

animals symbolising the root causes of suffering, the ‘three poisons’:

ignorance (pig), attachment (rooster), and anger (snake). The latter two

come out of the mouth of the pig: ignorance is the primary obstacle to

achieving anything, take note.