Free Online FOOD for MIND & HUNGER - DO GOOD 😊 PURIFY MIND.To live like free birds 🐦 🦢 🦅 grow fruits 🍍 🍊 🥑 🥭 🍇 🍌 🍎 🍉 🍒 🍑 🥝 vegetables 🥦 🥕 🥗 🥬 🥔 🍆 🥜 🎃 🫑 🍅🍜 🧅 🍄 🍝 🥗 🥒 🌽 🍏 🫑 🌳 🍓 🍊 🥥 🌵 🍈 🌰 🇧🇧 🫐 🍅 🍐 🫒Plants 🌱in pots 🪴 along with Meditative Mindful Swimming 🏊♂️ to Attain NIBBĀNA the Eternal Bliss.

Kushinara NIBBĀNA Bhumi Pagoda White Home, Puniya Bhumi Bengaluru, Prabuddha Bharat International.

08/30/22

Filed under: General, Theravada Tipitaka , Plant raw Vegan Broccoli, peppers, cucumbers, carrots

Posted by: site admin @ 9:32 pm

Posted by: site admin @ 9:32 pm

LESSON 4541 Wed 31 Aug 2022

MISSION BENEVOLENT UNIVERSE

WE WERE BENEVOLENT AWAKENED ONES

WE ARE BENEVOLENT AWAKENED ONES

WE CONTINUE TO BE BENEVOLENT AWAKENED ONES

Awakening and NIBBĀNA

Awakening and NIBBĀNA

Vinaya Pitaka

The Basket of the Discipline

54) Classical Benevolent Icelandic-Klassísk íslensku,

55) Classical Benevolent Igbo,Klassískt Igbo,

56) Classical Benevolent Ilocano,58) Klasiko nga Ilocano

57)Classical Benevolent Indonesian-Bahasa Indonesia Klasik,

58) Classical Benevolent Irish-Indinéisis Clasaiceach,

59) Classical Benevolent Italian-Italiano classico,

Vinaya Pitaka

The Basket of the Discipline

The Vinaya

Pitaka, the first division of the Tipitaka, is the textual framework

upon which the monastic community (Sangha) is built. It includes not

only the rules governing the life of every Theravada bhikkhu (monk) and

bhikkhuni (nun), but also a host of procedures and conventions of

etiquette that support harmonious relations, both among the monastics

themselves, and between the monastics and their lay supporters, upon

whom they depend for all their material needs.

Pitaka, the first division of the Tipitaka, is the textual framework

upon which the monastic community (Sangha) is built. It includes not

only the rules governing the life of every Theravada bhikkhu (monk) and

bhikkhuni (nun), but also a host of procedures and conventions of

etiquette that support harmonious relations, both among the monastics

themselves, and between the monastics and their lay supporters, upon

whom they depend for all their material needs.

When

the Buddha first established the Sangha, the community initially lived

in harmony without any codified rules of conduct. As the Sangha

gradually grew in number and evolved into a more complex society,

occasions inevitably arose when a member would act in an unskillful way.

Whenever one of these cases was brought to the Buddha’s attention, he

would lay down a rule establishing a suitable punishment for the

offense, as a deterrent to future misconduct. The Buddha’s standard

reprimand was itself a powerful corrective:

the Buddha first established the Sangha, the community initially lived

in harmony without any codified rules of conduct. As the Sangha

gradually grew in number and evolved into a more complex society,

occasions inevitably arose when a member would act in an unskillful way.

Whenever one of these cases was brought to the Buddha’s attention, he

would lay down a rule establishing a suitable punishment for the

offense, as a deterrent to future misconduct. The Buddha’s standard

reprimand was itself a powerful corrective:

It

is not fit, foolish man, it is not becoming, it is not proper, it is

unworthy of a recluse, it is not lawful, it ought not to be done. How

could you, foolish man, having gone forth under this Dhamma and

Discipline which are well-taught, [commit such and such offense]?… It

is not, foolish man, for the benefit of un-believers, nor for the

increase in the number of believers, but, foolish man, it is to the

detriment of both unbelievers and believers, and it causes wavering in

some.

is not fit, foolish man, it is not becoming, it is not proper, it is

unworthy of a recluse, it is not lawful, it ought not to be done. How

could you, foolish man, having gone forth under this Dhamma and

Discipline which are well-taught, [commit such and such offense]?… It

is not, foolish man, for the benefit of un-believers, nor for the

increase in the number of believers, but, foolish man, it is to the

detriment of both unbelievers and believers, and it causes wavering in

some.

— The Book of the Discipline, Part I, by I.B. Horner (London: Pali Text Society, 1982), pp. 36-37.

The

monastic tradition and the rules upon which it is built are sometimes

naïvely criticized — particularly here in the West — as irrelevant to

the “modern” practice of Buddhism. Some see the Vinaya as a throwback to

an archaic patriarchy, based on a hodge-podge of ancient rules and

customs — quaint cultural relics that only obscure the essence of “true”

Buddhist practice. This misguided view overlooks one crucial fact: it

is thanks to the unbroken lineage of monastics who have consistently

upheld and protected the rules of the Vinaya for almost 2,600 years that

we find ourselves today with the luxury of receiving the priceless

teachings of Dhamma. Were it not for the Vinaya, and for those who

continue to keep it alive to this day, there would be no Buddhism.

monastic tradition and the rules upon which it is built are sometimes

naïvely criticized — particularly here in the West — as irrelevant to

the “modern” practice of Buddhism. Some see the Vinaya as a throwback to

an archaic patriarchy, based on a hodge-podge of ancient rules and

customs — quaint cultural relics that only obscure the essence of “true”

Buddhist practice. This misguided view overlooks one crucial fact: it

is thanks to the unbroken lineage of monastics who have consistently

upheld and protected the rules of the Vinaya for almost 2,600 years that

we find ourselves today with the luxury of receiving the priceless

teachings of Dhamma. Were it not for the Vinaya, and for those who

continue to keep it alive to this day, there would be no Buddhism.

It

helps to keep in mind that the name the Buddha gave to the spiritual

path he taught was “Dhamma-vinaya” — the Doctrine (Dhamma) and

Discipline (Vinaya) — suggesting an integrated body of wisdom and

ethical training. The Vinaya is thus an indispensable facet and

foundation of all the Buddha’s teachings, inseparable from the Dhamma,

and worthy of study by all followers — lay and ordained, alike. Lay

practitioners will find in the Vinaya Pitaka many valuable lessons

concerning human nature, guidance on how to establish and maintain a

harmonious community or organization, and many profound teachings of the

Dhamma itself. But its greatest value, perhaps, lies in its power to

inspire the layperson to consider the extraordinary possibilities

presented by a life of true renunciation, a life lived fully in tune

with the Dhamma.

helps to keep in mind that the name the Buddha gave to the spiritual

path he taught was “Dhamma-vinaya” — the Doctrine (Dhamma) and

Discipline (Vinaya) — suggesting an integrated body of wisdom and

ethical training. The Vinaya is thus an indispensable facet and

foundation of all the Buddha’s teachings, inseparable from the Dhamma,

and worthy of study by all followers — lay and ordained, alike. Lay

practitioners will find in the Vinaya Pitaka many valuable lessons

concerning human nature, guidance on how to establish and maintain a

harmonious community or organization, and many profound teachings of the

Dhamma itself. But its greatest value, perhaps, lies in its power to

inspire the layperson to consider the extraordinary possibilities

presented by a life of true renunciation, a life lived fully in tune

with the Dhamma.

Contents

I. Suttavibhanga — the basic rules of conduct (Patimokkha) for

bhikkhus and bhikkhunis, along with the “origin story” for each one.

bhikkhus and bhikkhunis, along with the “origin story” for each one.

II. Khandhaka

A. Mahavagga — in addition to rules of conduct and etiquette for

the Sangha, this section contains several important sutta-like texts,

including an account of the period immediately following the Buddha’s

Awakening, his first sermons to the group of five monks, and stories of

how some of his great disciples joined the Sangha and themselves

attained Awakening.

the Sangha, this section contains several important sutta-like texts,

including an account of the period immediately following the Buddha’s

Awakening, his first sermons to the group of five monks, and stories of

how some of his great disciples joined the Sangha and themselves

attained Awakening.

B. Cullavagga — an elaboration of the bhikkhus’ etiquette and

duties, as well as the rules and procedures for addressing offences that

may be committed within the Sangha.

duties, as well as the rules and procedures for addressing offences that

may be committed within the Sangha.

III. Parivara — A recapitulation of the previous sections, with

summaries of the rules classified and re-classified in various ways for

instructional purposes.

summaries of the rules classified and re-classified in various ways for

instructional purposes.

Celibacy Quotes

The Early Vinaya Stand on Monastic Sexual Behaviour

Asanga Tilakaratne

(University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka)

< Islamic Perspective

John Paul II Chastity (1994) >

Souce: Buddhism.Org [broken link]

Introduction

Part 1 - Theravada Vinaya Stand on Celibacy

Part 2 - Celibacy as an essential aspect of the practice

Conclusion

References Cited

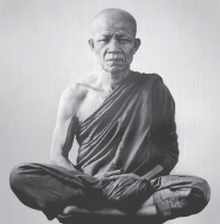

Buddhist Monk

This

article is presented as something of a curiosity. While it contains

good information, it consists basically of a scholarly survey of

legalism in effect in certain monasteries. Missing is any discussion of

the “why” of celibacy - i.e., the effects of celibacy on energies in the

mind and body, and the use of celibacy to hermetically seal the mind

against undesirable mental states and intrusive thoughts. (There is no

discussion of the harmful effects of unnatural sexual acts.) The brief

philosophy of celibacy in Part II is given in general Buddhistic terms

such as craving, pleasure-seeking, suffering, and renunciation.

article is presented as something of a curiosity. While it contains

good information, it consists basically of a scholarly survey of

legalism in effect in certain monasteries. Missing is any discussion of

the “why” of celibacy - i.e., the effects of celibacy on energies in the

mind and body, and the use of celibacy to hermetically seal the mind

against undesirable mental states and intrusive thoughts. (There is no

discussion of the harmful effects of unnatural sexual acts.) The brief

philosophy of celibacy in Part II is given in general Buddhistic terms

such as craving, pleasure-seeking, suffering, and renunciation.

top of page

Introduction

Celibacy

has been a key aspect of the Buddhist monastic life from the beginning.

In fact it has been prescribed for both householders and monks though

at two different levels. For the former, celibacy has been prescribed as

a part of their more intensive religious behaviour associated with the

observance of uposatha. [References Cited]

has been a key aspect of the Buddhist monastic life from the beginning.

In fact it has been prescribed for both householders and monks though

at two different levels. For the former, celibacy has been prescribed as

a part of their more intensive religious behaviour associated with the

observance of uposatha. [References Cited]

Uposatha

(Sanskrit: upavashatha) observance pre-dates Buddhism. It seems that

the practice was already there as a part of Indian religious life and

the Buddhists in fact adopted it partly on popular demand. [See Vinaya

II: Uposatha-khandhaka for details]

(Sanskrit: upavashatha) observance pre-dates Buddhism. It seems that

the practice was already there as a part of Indian religious life and

the Buddhists in fact adopted it partly on popular demand. [See Vinaya

II: Uposatha-khandhaka for details]

With

the gradual development of monasticism in Buddhism it seems that

specific modes of religious observance were evolved for the laity, an

important aspect of which was for them to spend a day in a monastery

undertaking to observe eight (attanga-sila) or ten precepts (dasa-sila),

a day during which householders are expected to undertake to observe

several more precepts than their regular five precepts.

the gradual development of monasticism in Buddhism it seems that

specific modes of religious observance were evolved for the laity, an

important aspect of which was for them to spend a day in a monastery

undertaking to observe eight (attanga-sila) or ten precepts (dasa-sila),

a day during which householders are expected to undertake to observe

several more precepts than their regular five precepts.

In

the regular five precepts what comes as refraining from sexual

misconduct [kaamesu micchaacaaraa veramani] becomes, under this special

observance, equal to what is observed by the monks and nuns, namely,

refraining from non-noble behaviour [abrahma-cariyaa veramani]. Whereas

total abstinence from sex is only optional for householders, for the

monks and nuns it has been mandatory from the beginning of the Sangha

organization.

the regular five precepts what comes as refraining from sexual

misconduct [kaamesu micchaacaaraa veramani] becomes, under this special

observance, equal to what is observed by the monks and nuns, namely,

refraining from non-noble behaviour [abrahma-cariyaa veramani]. Whereas

total abstinence from sex is only optional for householders, for the

monks and nuns it has been mandatory from the beginning of the Sangha

organization.

This

paper focuses basically on the practice of celibacy within the monastic

community, for it is in the context of monastic life that the full

import of the practice becomes clearly evident. In the monastic

discipline, Vinaya, rules and traditions related to sexual behaviour

become very important and hence one aspect of the paper will be to study

the mechanism of the Vianya rules associated with monastic sexual

behaviour. Since Vinaya receives its justification in the broader

context of the Buddhist religious practice aimed at attaining the

purification/liberation (visuddhi/vimutti) it is crucial for us to

understand the doctrinal justification of celibacy within the broader

context.

paper focuses basically on the practice of celibacy within the monastic

community, for it is in the context of monastic life that the full

import of the practice becomes clearly evident. In the monastic

discipline, Vinaya, rules and traditions related to sexual behaviour

become very important and hence one aspect of the paper will be to study

the mechanism of the Vianya rules associated with monastic sexual

behaviour. Since Vinaya receives its justification in the broader

context of the Buddhist religious practice aimed at attaining the

purification/liberation (visuddhi/vimutti) it is crucial for us to

understand the doctrinal justification of celibacy within the broader

context.

The

paper will be organized in the following manner: the first part will

discuss the Vianya or the disciplinary rules related to monastic

celibacy. The second part will discuss the doctrinal foundations of this

practice. For the first section my main sources will be the Theravada

Pali Vinaya literature, namely, the Vinaya-pitaka and its commentary by

Buddhaghosa. More recent secondary literature will be cited for further

clarification. For the second the main sources will be in addition to

the Vinaya-pitaka,the Sutta-pitaka or the discourses in the Pali canon.

Although the title of the paper highlights the first parajika relevant

to the bhikkhu (male) sangha, the similar rules relevant to the

bhikkhuni (female) sangha and the other subsidiary rules associated with

the sexual relations between bhikkhu and bhikkhuni sangha will also be

discussed.

paper will be organized in the following manner: the first part will

discuss the Vianya or the disciplinary rules related to monastic

celibacy. The second part will discuss the doctrinal foundations of this

practice. For the first section my main sources will be the Theravada

Pali Vinaya literature, namely, the Vinaya-pitaka and its commentary by

Buddhaghosa. More recent secondary literature will be cited for further

clarification. For the second the main sources will be in addition to

the Vinaya-pitaka,the Sutta-pitaka or the discourses in the Pali canon.

Although the title of the paper highlights the first parajika relevant

to the bhikkhu (male) sangha, the similar rules relevant to the

bhikkhuni (female) sangha and the other subsidiary rules associated with

the sexual relations between bhikkhu and bhikkhuni sangha will also be

discussed.

top of page

I. The Theravada Vinaya Stand on Celibacy

It

is important to note at the beginning that the Vinaya rule connected

with celibacy is the very first of the rules counting among the most

severe in the degree of violation, and it is common for both bhikkhu and

bhikkhuni sangha. The four rules included in the first category,

namely, parajika, are so called for the particular violations amount to

the “defeat” of the offending member [of the monastery]. What this term

exactly means is given in the Vianaya: Like a person, whose head is cut

off, is unable to live with that mutilated body, a bhikkhu having

associated with sex becomes a non-samana and non-sakyan-son (i.e. loses

his monkhood and the membership among the Buddha’s sangha).

is important to note at the beginning that the Vinaya rule connected

with celibacy is the very first of the rules counting among the most

severe in the degree of violation, and it is common for both bhikkhu and

bhikkhuni sangha. The four rules included in the first category,

namely, parajika, are so called for the particular violations amount to

the “defeat” of the offending member [of the monastery]. What this term

exactly means is given in the Vianaya: Like a person, whose head is cut

off, is unable to live with that mutilated body, a bhikkhu having

associated with sex becomes a non-samana and non-sakyan-son (i.e. loses

his monkhood and the membership among the Buddha’s sangha).

Paaraajiko hotiiti seyyathaapi naama puriso siisacchinno ababbho

tena sariirabandhanena jivitum,evam eva bhikkhu methunam dhammamam

patisevitvaa asamano hoti askyaputtiyo, tena vuccati paaraajiko hotiiti.

(Vinaya III p.28.)

This

shows that the sense of “defeat”, amounting to losing one’s monkhood,

has much stronger connotation than it would usually believed to contain.

By violating this rule one becomes “un-associable” (asamvaasa) by the

Sangha, which technically means that the Sangha cannot execute vinaya

acts having him/her as a member, cannot recite the Vinaya together and

does not share the same mode of training with the particular person any

more.

shows that the sense of “defeat”, amounting to losing one’s monkhood,

has much stronger connotation than it would usually believed to contain.

By violating this rule one becomes “un-associable” (asamvaasa) by the

Sangha, which technically means that the Sangha cannot execute vinaya

acts having him/her as a member, cannot recite the Vinaya together and

does not share the same mode of training with the particular person any

more.

Asamvaasoti samvaaso naama ekakammam ekuddeso samasikkhaa, eso

samvaaso naama, so tena saddhim natthi, tena vuccati asamvaasoti.

(Vinaya III p.28.)

The

first parajika rule has the main prohibition with two specifications.

The main rule goes as: whoever bhikkhu engages in sexual act becomes

defeated and un-associable [yo pana bhikkhu methunam dhammam patiseveyya

paarajiko hoti asamvaaso].

first parajika rule has the main prohibition with two specifications.

The main rule goes as: whoever bhikkhu engages in sexual act becomes

defeated and un-associable [yo pana bhikkhu methunam dhammam patiseveyya

paarajiko hoti asamvaaso].

This

original rule was enacted due to sexual intercourse by the monk named

Sudinna with his former wife. It is known that the Buddha did not enact

vinaya rules until the conditions tha necessitated doing were there and a

tradition going back to the early period has that during the first

twenty years of the Sangha there were not any regulated vinaya rules,

but, instead the disciples were guided by the Dhamma itself. The

Sudinna’s case is considered to be first serious matter that arose

within the Sangha.

original rule was enacted due to sexual intercourse by the monk named

Sudinna with his former wife. It is known that the Buddha did not enact

vinaya rules until the conditions tha necessitated doing were there and a

tradition going back to the early period has that during the first

twenty years of the Sangha there were not any regulated vinaya rules,

but, instead the disciples were guided by the Dhamma itself. The

Sudinna’s case is considered to be first serious matter that arose

within the Sangha.

The

conditions under which Sudinna had to have sex with his former wife are

quite clear; he was the only son of a rich family not wanting to lose

their son and also not wanting see their vast property perished in the

absence of heir, they first tried their best to avert him from his

decision to join the Sangha, once it failed and when he visited his

parents at their house for the first time again they tried to lure him

back and having failed in both efforts the mother made a plea that at

least he should produce a heir to their family to which Sudinna had to

agree. Consequently he had sex with his wife with the intention of

impregnating her [an act which actually caused pregnancy].

conditions under which Sudinna had to have sex with his former wife are

quite clear; he was the only son of a rich family not wanting to lose

their son and also not wanting see their vast property perished in the

absence of heir, they first tried their best to avert him from his

decision to join the Sangha, once it failed and when he visited his

parents at their house for the first time again they tried to lure him

back and having failed in both efforts the mother made a plea that at

least he should produce a heir to their family to which Sudinna had to

agree. Consequently he had sex with his wife with the intention of

impregnating her [an act which actually caused pregnancy].

By

this time there was no rule prohibiting the act of this nature. The

Vinaya says that he did so not seeing the disadvantages of the act

[apannatte vinaye anaadiinavadasso …] (Vinaya III. p.18). But his

subsequent behaviour characterized by remorse shows that he was not

“innocent” in his mind. I will come to this point later. When the Buddha

came to know the incident he enacted the rule prohibiting sexual

intercourse.

this time there was no rule prohibiting the act of this nature. The

Vinaya says that he did so not seeing the disadvantages of the act

[apannatte vinaye anaadiinavadasso …] (Vinaya III. p.18). But his

subsequent behaviour characterized by remorse shows that he was not

“innocent” in his mind. I will come to this point later. When the Buddha

came to know the incident he enacted the rule prohibiting sexual

intercourse.

Two

clauses, “at least with a female animal” [antamaso

tiracchaanagataayapi] and “having made commitment to the training of

bhikkhus, without giving up the training and without admitting the

weakness” [bhikkhuunam sikkhaasaajiiva-samaapanno sikkham apaccakkhaaya

dubbalyam anaavikatvaa] were added due to subsequent developments.

clauses, “at least with a female animal” [antamaso

tiracchaanagataayapi] and “having made commitment to the training of

bhikkhus, without giving up the training and without admitting the

weakness” [bhikkhuunam sikkhaasaajiiva-samaapanno sikkham apaccakkhaaya

dubbalyam anaavikatvaa] were added due to subsequent developments.

The

first had to be when a monk had sex with a female monkey thinking that

what is prohibited is only sex with humans, and the next was added when

some monks who got deprived by having sex wanted to return to the Sangha

confessing their subsequent admittance of wrong-doing. The second

specification allows that if a monk who had sex did so having distanced

himself from the training and having admitted his inability to conform

to the rule, he could return later to the Sangha.

first had to be when a monk had sex with a female monkey thinking that

what is prohibited is only sex with humans, and the next was added when

some monks who got deprived by having sex wanted to return to the Sangha

confessing their subsequent admittance of wrong-doing. The second

specification allows that if a monk who had sex did so having distanced

himself from the training and having admitted his inability to conform

to the rule, he could return later to the Sangha.

The

case is clear for in fact by doing as indicated in the specification a

monk gives back his monkhood to the Sangha and thereby becomes an

ordinary householder, who is beyond the jurisdiction of the Vinaya and

whose behaviour consequently would not amount to violating the rule.

Such a person may return to the Sangha provided that he or she were to

display the proper attitude toward the Vinaya.

case is clear for in fact by doing as indicated in the specification a

monk gives back his monkhood to the Sangha and thereby becomes an

ordinary householder, who is beyond the jurisdiction of the Vinaya and

whose behaviour consequently would not amount to violating the rule.

Such a person may return to the Sangha provided that he or she were to

display the proper attitude toward the Vinaya.

One

who did not fulfill this requirement should not be accepted if he or

she were to return. The Buddha clearly says that a person fulfilled the

requirement should be accepted and granted upasampadaa on return and one

who did not conform to it must not be given upasampadaa. (Vinaya III.

p.23)

who did not fulfill this requirement should not be accepted if he or

she were to return. The Buddha clearly says that a person fulfilled the

requirement should be accepted and granted upasampadaa on return and one

who did not conform to it must not be given upasampadaa. (Vinaya III.

p.23)

The

Pali word used here is “na upasampaadetabbo” meaning, “should not be

given upasampadaa” [full membership], and not “na pabbaajetabbo” meaning

“should not be given pabbajjaa” [initial leaving of household life],

which seems to imply that such a person still may be accepted as a

samanera [novice]. (Vinaya III. p.23). With the addition of two

specifications the complete rule on the first parajika reads as: whoever

monk, without giving up the training, and without revealing his

weakness, were to have sex even with a female animal becomes defeated

and unassociable.

Pali word used here is “na upasampaadetabbo” meaning, “should not be

given upasampadaa” [full membership], and not “na pabbaajetabbo” meaning

“should not be given pabbajjaa” [initial leaving of household life],

which seems to imply that such a person still may be accepted as a

samanera [novice]. (Vinaya III. p.23). With the addition of two

specifications the complete rule on the first parajika reads as: whoever

monk, without giving up the training, and without revealing his

weakness, were to have sex even with a female animal becomes defeated

and unassociable.

Yo pana bhikkhu bhikkhuunam sikkhaasaajiiva-samaapanno sikkham

apaccakkhaaya dubbalyam anaavikatvaa methunam dhammam patiseveyya

anatamaso tiracchaanagataayapi paaraajiko hoti aamvaso.

In

the specific context of the rule what is meant by the sexual activity

[methuna-dhamma] is sex between man and woman. However, the rule was

meant to be understood more broadly and more precisely. The phrase

“engages in sex” [methunam dhammam patisevati] has been described

defining what sex means and what engaging in sex means. Sex is defined

as “that which is improper phenomenon, uncultured phenomenon, lowly

phenomenon, lewd, requiring cleansing by water, covert, requiring the

engagement between two [people].

the specific context of the rule what is meant by the sexual activity

[methuna-dhamma] is sex between man and woman. However, the rule was

meant to be understood more broadly and more precisely. The phrase

“engages in sex” [methunam dhammam patisevati] has been described

defining what sex means and what engaging in sex means. Sex is defined

as “that which is improper phenomenon, uncultured phenomenon, lowly

phenomenon, lewd, requiring cleansing by water, covert, requiring the

engagement between two [people].

Methunadhammo naama: yo so asaddhammo gaamadhammo vasaladhammo

dutthullam odakantikam rahassam dvayamdvaya samaapatti, eso

methunadhammo naama (Vinaya III. p.28).

The

engagement in such act has been described as “inserting of the mark

with the mark or sex organ with the sex organ at least to the amount of

mustard seed.

engagement in such act has been described as “inserting of the mark

with the mark or sex organ with the sex organ at least to the amount of

mustard seed.

Patisevatinaama: yo nimittena nimittam angajaatena angajaatam

antamaso tilaphalamattampi paveseti, eso patisevati naama (Vinaya III.

p.28).

antamaso tilaphalamattampi paveseti, eso patisevati naama (Vinaya III.

p.28).

In

the definition of sex, the fact that association of two people has been

given as a requirement is important for us to understand the nature of

sex referred to here. In the subsequent description of engaging in sex,

although involvement of two sexual organs and penetration are mentioned,

giving thereby an impression of heterosexual sex, in its technical

analysis what the rule specifies is not mere vaginal sex but sex in any

one of the three modes, namely, vaginal, anal and oral, the three modes

being referred to as “three paths” [tayo maggaa].

the definition of sex, the fact that association of two people has been

given as a requirement is important for us to understand the nature of

sex referred to here. In the subsequent description of engaging in sex,

although involvement of two sexual organs and penetration are mentioned,

giving thereby an impression of heterosexual sex, in its technical

analysis what the rule specifies is not mere vaginal sex but sex in any

one of the three modes, namely, vaginal, anal and oral, the three modes

being referred to as “three paths” [tayo maggaa].

This

broadens the definition of the partner of sex, not confining to

heterosexual act but sexual act between any two partners, whether or not

belonging to the same sex. What really matters is whether or not sex

act involves any of the “three paths” and not sex of those who are

engaged in. In the technical analysis, following this convention, three

females are identified as human, non-human and animal females and three

males are identified as human, non-human and animal males.

broadens the definition of the partner of sex, not confining to

heterosexual act but sexual act between any two partners, whether or not

belonging to the same sex. What really matters is whether or not sex

act involves any of the “three paths” and not sex of those who are

engaged in. In the technical analysis, following this convention, three

females are identified as human, non-human and animal females and three

males are identified as human, non-human and animal males.

[Although

the category of non-human may be taken as including all non human

members including animals, in the Pali usage “a-manussa” is usually

taken to mean only non-human counterparts in sub-divine, demon or

hungry-ghost spheres, and not even those who belong to the divine

sphere.]

the category of non-human may be taken as including all non human

members including animals, in the Pali usage “a-manussa” is usually

taken to mean only non-human counterparts in sub-divine, demon or

hungry-ghost spheres, and not even those who belong to the divine

sphere.]

Although

the involvement of two people has been mentioned in the definition of

the sex act [as we above], an incident, mentioned in the “case studies”

[viniita-vatthu], of a monk who took his own member by his own mouth and

who inserted his own member in his own anus have been judged to have

violated the rule and guilty of parajika offence. Vinaya III. p.35.

Series of incidents involving dead bodies show that the rule applies

equally even if the “partner” is not alive.

the involvement of two people has been mentioned in the definition of

the sex act [as we above], an incident, mentioned in the “case studies”

[viniita-vatthu], of a monk who took his own member by his own mouth and

who inserted his own member in his own anus have been judged to have

violated the rule and guilty of parajika offence. Vinaya III. p.35.

Series of incidents involving dead bodies show that the rule applies

equally even if the “partner” is not alive.

The

next category of offences - which is called “sanghaadisesa”, for the

recovery process from the violation requires the participation of the

Sangha at the beginning and at the end [i.e., formal meeting of the

Sangha] - begins with sex that does not involve the “three paths”

mentioned above. It is important to note that this act is not described

as methuna-dhamma or sexual act, and consequently the violators are not

considered as “defeated”.

next category of offences - which is called “sanghaadisesa”, for the

recovery process from the violation requires the participation of the

Sangha at the beginning and at the end [i.e., formal meeting of the

Sangha] - begins with sex that does not involve the “three paths”

mentioned above. It is important to note that this act is not described

as methuna-dhamma or sexual act, and consequently the violators are not

considered as “defeated”.

The

relevant rule goes as: intentional emission of semen, unless in a

dream, involves the sanghaadisesa offence. [Sancetanika sukka-visatthi

annatra supinantaa sanghaadiseso (Vinaya III. p.112)]. This rule covers

any sexual act not involving any of the paths, executed within oneself

or between two people.

relevant rule goes as: intentional emission of semen, unless in a

dream, involves the sanghaadisesa offence. [Sancetanika sukka-visatthi

annatra supinantaa sanghaadiseso (Vinaya III. p.112)]. This rule covers

any sexual act not involving any of the paths, executed within oneself

or between two people.

The

origin of the rule is a group of monks who engaged in masturbation. The

case studies, however, refer to incidents between two monks but not

involving paths. The two conditions, having intention and emission of

semen both have to be fulfilled in order one to be considered guilty.

This means that if emission happens even in a sexually provocative act

or in an act motivated by sexual desire but emission is not intended or

in an act meant for emission but emission does not happen, the monk

concerned has been considered not guilty technically.

origin of the rule is a group of monks who engaged in masturbation. The

case studies, however, refer to incidents between two monks but not

involving paths. The two conditions, having intention and emission of

semen both have to be fulfilled in order one to be considered guilty.

This means that if emission happens even in a sexually provocative act

or in an act motivated by sexual desire but emission is not intended or

in an act meant for emission but emission does not happen, the monk

concerned has been considered not guilty technically.

In

addition to this rule involving “second degree” sex, there are four

other rules belonging to the same category, related to sexual desire,

namely:

addition to this rule involving “second degree” sex, there are four

other rules belonging to the same category, related to sexual desire,

namely:

touching a woman’s body with a perverted mind (sanghaadisesa rule #2);

speaking lewd words to a woman with a perverted mind (rule #3);

speaking with a perverted mind, in the presence of woman, in praise of administering to one’s sexual needs (rule #4);

and functioning as a go-between carrying man’s sexual intentions to a woman or vice versa (rule #5).

Although

these rules do not involve any direct sexual act in themselves, such

behaviour has been considered serious violations due to their obvious

unhealthy impact on celibate life.

these rules do not involve any direct sexual act in themselves, such

behaviour has been considered serious violations due to their obvious

unhealthy impact on celibate life.

It

is interesting to note that the parajika field for the bhikkhunis is

much broader that that of bhikkhus, in addition to their being bound by

the almost identical first rule related to having sex with a male

partner.

is interesting to note that the parajika field for the bhikkhunis is

much broader that that of bhikkhus, in addition to their being bound by

the almost identical first rule related to having sex with a male

partner.

Yaa pana bhikkhunii chandaso methunam dhammam patiseveyya antamaso tiracchaanagatenaapi paaraajikaa hoti asamvaasaa.

The

rule is not completely identical for it does not have the clause

concerning giving up the training and revealing weakness, which is a

concession for those former bhikkhus wished to come back. [human,

non-human or animal] They have two additional parajika offences not

involving direct sexual intercourse but physical touch with a man, which

are as follows:

rule is not completely identical for it does not have the clause

concerning giving up the training and revealing weakness, which is a

concession for those former bhikkhus wished to come back. [human,

non-human or animal] They have two additional parajika offences not

involving direct sexual intercourse but physical touch with a man, which

are as follows:

Whatever bhikkhuni overflowing with desire, should consent to the

rubbing or rubbing up against or taking hold of or touching or pressing

against, below the collarbone, above the circle of the knees, of a male

person who is overflowing with desire, she too becomes defeated, not in

communion. (rule #5)

rubbing or rubbing up against or taking hold of or touching or pressing

against, below the collarbone, above the circle of the knees, of a male

person who is overflowing with desire, she too becomes defeated, not in

communion. (rule #5)

Whatever bhikkhuni overflowing with desire for the sake of following

what is verily not the rule, should consent to the holding of the hand

by a male person who is overflowing with desire or should consent to

theholding of the edge of [her] outer cloak or should stand or should

talk or should go to a rendezvous or should consent to a man’s

approaching [her] or should enter into a covered place or should dispose

the body for such a purpose, she too becomes defeated, not in

communion. (rule #8 Translation from K.R. Norman in The Patimokkha, ed.

by William Pruitt, PTS, 2001.pp. 119 & 121.).

what is verily not the rule, should consent to the holding of the hand

by a male person who is overflowing with desire or should consent to

theholding of the edge of [her] outer cloak or should stand or should

talk or should go to a rendezvous or should consent to a man’s

approaching [her] or should enter into a covered place or should dispose

the body for such a purpose, she too becomes defeated, not in

communion. (rule #8 Translation from K.R. Norman in The Patimokkha, ed.

by William Pruitt, PTS, 2001.pp. 119 & 121.).

What

is covered by these additional two parajika rules [NB. bhikkhunis have

altogether eight parajika rules.] seems to have been included within the

category of the sanghaadisesa in the case of bhikkhus. What is

interesting to note is that there is no sanghaadisesa rule for the

bhikkhunis corresponding to the first of that category of rules for the

bhikkhus involving sex other than three paths.

is covered by these additional two parajika rules [NB. bhikkhunis have

altogether eight parajika rules.] seems to have been included within the

category of the sanghaadisesa in the case of bhikkhus. What is

interesting to note is that there is no sanghaadisesa rule for the

bhikkhunis corresponding to the first of that category of rules for the

bhikkhus involving sex other than three paths.

For

the bhikkhunis sexual intercourse has been conceived solely as

heterosexual act involving a male partner. Although there is no evidence

in the Vinaya to suggest that it was aware of lesbianism involving two

women, precaution has been taken against bhikkhunis engaging in

activities generating self-stimulation.

the bhikkhunis sexual intercourse has been conceived solely as

heterosexual act involving a male partner. Although there is no evidence

in the Vinaya to suggest that it was aware of lesbianism involving two

women, precaution has been taken against bhikkhunis engaging in

activities generating self-stimulation.

In

addition to the rules concerning sexual acts or sexually oriented

behaviour there are good number of rules for both bhikkhus and

bhikkhunis that make sense only in the context of sexual behaviour. For

instance, in the case of bhikkhus, in addition to the parajika and

sanghaadisesa offences discussed above, there are following rules of

varying degrees of gravity:

addition to the rules concerning sexual acts or sexually oriented

behaviour there are good number of rules for both bhikkhus and

bhikkhunis that make sense only in the context of sexual behaviour. For

instance, in the case of bhikkhus, in addition to the parajika and

sanghaadisesa offences discussed above, there are following rules of

varying degrees of gravity:

i. Indefinite [aniyata]: two offences, one involving sitting with a

woman privately in a screened seat convenient enough for sexual

intercourse, and the other sitting in a place convenient enough not for

having sex but for addressing her with lewd words. These two are called

indefinite because the wrong-doing has to be determined on the word of a

female follower [upaasikaa] who is trustworthy and who brings forth the

chargeand the admittance by the person involved; accordingly the person

may be charged either with parajika or with sanghaadisesa.

woman privately in a screened seat convenient enough for sexual

intercourse, and the other sitting in a place convenient enough not for

having sex but for addressing her with lewd words. These two are called

indefinite because the wrong-doing has to be determined on the word of a

female follower [upaasikaa] who is trustworthy and who brings forth the

chargeand the admittance by the person involved; accordingly the person

may be charged either with parajika or with sanghaadisesa.

ii. Offence entailing expiation with forfeiture [nissaggiya

paacittiya]: the fifth rule in this category prohibits a monk from

accepting a robe from bhikkhuni who is not related. He may do so only

when it is an exchange of robe.

paacittiya]: the fifth rule in this category prohibits a monk from

accepting a robe from bhikkhuni who is not related. He may do so only

when it is an exchange of robe.

Offences

involving expiation [paacittiya]: the following offences involving

expiation seem to be relevant for the present discussion:

involving expiation [paacittiya]: the following offences involving

expiation seem to be relevant for the present discussion:

sharing the same bed together with a woman [rule #6];

teaching Dhamma to a woman exceeding five or six sentences in the absence of a knowledgeable man [rule #7];

exhorting bhikkhunis without approval of the Sangha [rule #21];

even approved by the Sangha, exhorting after he Sun has set [rule #22];

exhorting a bhikkhuni having gone to her quarters except when a bhikkhuni is not well [rule #23];

giving robe material to a non-related bhikkhuni, except exchange [rule #25];

sewing a robe for or have a robe sewn by a bhikkhuni who is not related [rule #26];

setting out on the same journey, by arrangement, with a bhikkhuni

even to the next village except at the proper time [rule #27];

even to the next village except at the proper time [rule #27];

embark with a bhikkhuni, by arrangement, on a boat journey other than crossing over [rule #28];

eating knowingly food prepared by a bhikkhuni, other than by a prior arrangement with the householder [rule #29];

taking a seat with a bhikkhuni privately, one man with one woman [rule #30];

taking a seat with a woman on a screened seat [rule #44];

taking a seat with a woman privately , one man with one woman [rule # 45];

setting out on the same journey, by arrangement, with a woman, even to the next village [rule #67].

The

purpose of the rules seems to prevent any situation that could be

conducive for any mutual intimacy causing damage to one’s celibate life.

purpose of the rules seems to prevent any situation that could be

conducive for any mutual intimacy causing damage to one’s celibate life.

In

the case of bhikkhunis, in addition to the parajika rules, there are

subsidiary rules of varying degree of gravity hat can be made sense only

in the context of celibate life. They are as follows:

the case of bhikkhunis, in addition to the parajika rules, there are

subsidiary rules of varying degree of gravity hat can be made sense only

in the context of celibate life. They are as follows:

i. Offences entailing the formal meeting of the Sangha [sanghaadisesa]:

herself overflowing with desire, accepting with her own hand food

from the hands of a man overflowing with desire and partaking of it

[rule #5];

from the hands of a man overflowing with desire and partaking of it

[rule #5];

instructing a bhikkhuni to ignore whether or not the man offering food

is overflowing with desire, but accept with her own hands such food and

partake of it since she herself is not overflowing with desire [rule

#6];

is overflowing with desire, but accept with her own hands such food and

partake of it since she herself is not overflowing with desire [rule

#6];

acting as a go-between conveying man’s sexual desire to woman or vice versa [rule #7].

[NB.

There are no indefinite [aniyata] offences for bhikkhunis, and none of

the thirty offences of expiation involving forfeiture

[nisaggiya-pacittiya] seem to be relevant for the present discussion.]

There are no indefinite [aniyata] offences for bhikkhunis, and none of

the thirty offences of expiation involving forfeiture

[nisaggiya-pacittiya] seem to be relevant for the present discussion.]

ii. Offences entailing expiation [paacittiya]:

Slapping [genital] with the palms of the hand [rule #3];

using a wax-stick [for stimulation] (rule #4);

washing [genital] inserting the fingers more than two finger-joints (rule #5);

standing together or talking together, one woman with one man, in the dark of the night when there is no light [rule #11];

standing together or talking with a man, one woman with one man, in a screened place [rule #12];

standing together or talking with a man, one woman with one man, in an open place [rule #13];

standing together with or talking with a man, one woman with one

man, in a carriage or in a cul-de-sac or at crossroads or should whisper

in his ear or should dismiss the bhikkhuni who is her companion [rule

#14];

man, in a carriage or in a cul-de-sac or at crossroads or should whisper

in his ear or should dismiss the bhikkhuni who is her companion [rule

#14];

not giving up

keeping company with a householder or a householder son even when she is

advised against it by the other bhikkhunis [rue # 36];

keeping company with a householder or a householder son even when she is

advised against it by the other bhikkhunis [rue # 36];

entering into park with bhikkhus knowingly and without permission [rule # 51];

without having obtained permission from the Sangha or from the group

should sit together with a man, one woman with one man, make a boil or a

scab that has formed on the lower part of her body burst or break or

have it be washed or smeared or bound up or unbound [rule #60];

should sit together with a man, one woman with one man, make a boil or a

scab that has formed on the lower part of her body burst or break or

have it be washed or smeared or bound up or unbound [rule #60];

ordaining a trainee who keeps company with men, youths, who is a dwelling place for grief [rule #79];

making one’s bed with a man [rule #102];

teaching Dhamma to man more than five or six sentences [rule #103];

taking a seat with a man privately on a screened seat [rule #125];

and taking seat with a man privately, one woman with one man [rule #126].

This

study of the rules involving peripheral offences other than parajika or

sanghaadisesa directly involving sexual intercourse or behaviour show

how the tradition has strived to keep its monastic members right on its

focus. The discussion of this section may be summarized by highlighting

the emphasis put on limiting the heterosexual relations of bhikkhus and

bhikkhunis into non-sexual spheres.

study of the rules involving peripheral offences other than parajika or

sanghaadisesa directly involving sexual intercourse or behaviour show

how the tradition has strived to keep its monastic members right on its

focus. The discussion of this section may be summarized by highlighting

the emphasis put on limiting the heterosexual relations of bhikkhus and

bhikkhunis into non-sexual spheres.

top of page

II. Celibacy as an essential aspect of the practice - Soteriological significance of celibacy

Soteriology = salvation theory: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soteriology

We

need to understand the rationale behind the first parajikaa: why having

sex by bhikkhus and bhikkhunis has been considered to be so grave that

it was made the first of the most serious of offences.

need to understand the rationale behind the first parajikaa: why having

sex by bhikkhus and bhikkhunis has been considered to be so grave that

it was made the first of the most serious of offences.

In

a way, this is not hard to explain viewing the phenomenon from the

point of view of the crux of the Buddha’s realization, namely, the four

noble truths. The first two aspects of the teaching say that the people

in the world are suffering and that they undergo various forms of

suffering due to the “thirst” [tanhaa] they have for the pleasurable

Anguttara-nikaya, pp.1-2.objects [kaama-tanhaa], for becoming

[bhava-tanhaa]and for nonbecoming [vibhava-tanhaa]. The last two say

that cessation of this thirst is the end of suffering and the path to be

followed is the noble eightfold path.

a way, this is not hard to explain viewing the phenomenon from the

point of view of the crux of the Buddha’s realization, namely, the four

noble truths. The first two aspects of the teaching say that the people

in the world are suffering and that they undergo various forms of

suffering due to the “thirst” [tanhaa] they have for the pleasurable

Anguttara-nikaya, pp.1-2.objects [kaama-tanhaa], for becoming

[bhava-tanhaa]and for nonbecoming [vibhava-tanhaa]. The last two say

that cessation of this thirst is the end of suffering and the path to be

followed is the noble eightfold path.

The

root of the problem according to this diagnosis being the thirst for

pleasurable things, the other two aspects of thirst being dependent on

the first, the need to get rid of the thirst for pleasures is obvious.

root of the problem according to this diagnosis being the thirst for

pleasurable things, the other two aspects of thirst being dependent on

the first, the need to get rid of the thirst for pleasures is obvious.

The

pleasures in question are the ones associated with the five faculties,

forms, sounds, smells, tastes and contacts associated respectively with

eye, ear, nose, tongue and body. The mental phenomena associated with

mind too are included in this category. It is believed that all the

basic five forms of pleasures are obtained in sexual relations. This is

emphatically stated by the Buddha when he said that he cannot see any

other form, sound, smell, taste or touch more attractive to a man than

those belonging to a woman and vice versa. This, of course, assumes a

universe where homosexuality or lesbianism was not fully identified.

pleasures in question are the ones associated with the five faculties,

forms, sounds, smells, tastes and contacts associated respectively with

eye, ear, nose, tongue and body. The mental phenomena associated with

mind too are included in this category. It is believed that all the

basic five forms of pleasures are obtained in sexual relations. This is

emphatically stated by the Buddha when he said that he cannot see any

other form, sound, smell, taste or touch more attractive to a man than

those belonging to a woman and vice versa. This, of course, assumes a

universe where homosexuality or lesbianism was not fully identified.

The

gratification of senses, kaama-sukhallika-anuyoga as the very first

discourse of the Buddha puts it, has been described as “low, vulgar and

belonging to the ordinary”hiino, gammo, pothujjaniko.” Samyutta-nikaya

V. p.421.

gratification of senses, kaama-sukhallika-anuyoga as the very first

discourse of the Buddha puts it, has been described as “low, vulgar and

belonging to the ordinary”hiino, gammo, pothujjaniko.” Samyutta-nikaya

V. p.421.

The

discourses are plentiful with calamities and the multifarious

sufferings associated with search for pleasures. For example, the

Mahadukkhakkhandha-sutta of the Majjhima-nikaya details so many forms of

suffering people undergo due to pleasures. The Buddha says:

discourses are plentiful with calamities and the multifarious

sufferings associated with search for pleasures. For example, the

Mahadukkhakkhandha-sutta of the Majjhima-nikaya details so many forms of

suffering people undergo due to pleasures. The Buddha says:

With sensual pleasures as the cause, sensual pleasures as the

source, sensual pleasures as the basis, the cause being simply sensual

pleasures, kings quarrel with kings, nobles with nobles, Brahmins with

Brahmins, householders with householders, mother quarrels with the son,

son with mother, father with son, son with father, brother quarrels with

brother, brother with sister, sister with brother, friend with friend.

And here in their quarrels, brawls, and disputes they attack each other

with fists, clods, sticks, or knives, whereby they incur death or deadly

suffering. [Translation from Bhikkhu Nanamoli & Bhikkhu Bodhi,

1995/2001. p.181]

source, sensual pleasures as the basis, the cause being simply sensual

pleasures, kings quarrel with kings, nobles with nobles, Brahmins with

Brahmins, householders with householders, mother quarrels with the son,

son with mother, father with son, son with father, brother quarrels with

brother, brother with sister, sister with brother, friend with friend.

And here in their quarrels, brawls, and disputes they attack each other

with fists, clods, sticks, or knives, whereby they incur death or deadly

suffering. [Translation from Bhikkhu Nanamoli & Bhikkhu Bodhi,

1995/2001. p.181]

Ratthapala,

one among many young householders who left life full of pleasures for

monkhood, explains to King Koravya the reasons behind his renunciation

in the following words:

one among many young householders who left life full of pleasures for

monkhood, explains to King Koravya the reasons behind his renunciation

in the following words:

Sensual pleasures, varied, sweet, delightful

In many different ways disturb the mind

Seeing the danger in these sensual ties

I chose to lead the homeless life, O King.

Ratthapala-sutta, Majjhimanikaya 82. [translation from Bhikkhu Nanamoli and Bhikkhu Bodhi 1995/2001. p.691].

One

could go on and on quoting texts to support this position. But how the

early Buddhist tradition identifies the cause of the problem is beyond

doubt.

could go on and on quoting texts to support this position. But how the

early Buddhist tradition identifies the cause of the problem is beyond

doubt.

It

is only rational for those who perceived the problem in this manner to

adopt a life distanced from sensual pleasures, and naturally the

monastic life was considered ideal for the purpose. Putting it in the

words of very Ratthapala referred to above:

is only rational for those who perceived the problem in this manner to

adopt a life distanced from sensual pleasures, and naturally the

monastic life was considered ideal for the purpose. Putting it in the

words of very Ratthapala referred to above:

Venerable sir, as I understand the Dhamma taught by the Blessed One,

it is not easy while living in a home to lead the holy life, utterly

perfect and pure as a polished shell. Venerable sir, I wish to shave off

my hair and beard, put on the yellow robe, and go forth from the home

life into homelessness. I would receive the going forth under the

Blessed One, I would receive the full admission [Ibid. p.678.].

it is not easy while living in a home to lead the holy life, utterly

perfect and pure as a polished shell. Venerable sir, I wish to shave off

my hair and beard, put on the yellow robe, and go forth from the home

life into homelessness. I would receive the going forth under the

Blessed One, I would receive the full admission [Ibid. p.678.].

When

the monastic life is defined in this manner vis-a-vis the household

life characterized by gratification of senses it is natural to

understand the monkhood as defined by celibacy.

the monastic life is defined in this manner vis-a-vis the household

life characterized by gratification of senses it is natural to

understand the monkhood as defined by celibacy.

It

is in this context that the Vinaya remark about Sudinna that he did not

know the repercussions of his action when he did that becomes

unacceptable, as Dhirasekera, a distinguished scholar of Theravada

Vinaya, has pointed out:

is in this context that the Vinaya remark about Sudinna that he did not

know the repercussions of his action when he did that becomes

unacceptable, as Dhirasekera, a distinguished scholar of Theravada

Vinaya, has pointed out:

It is difficult to maintain here that anadinavadasso means that

Sudinna did not know that his act was an offence against the spirit of

Buddhist monasticism. Two things preclude us from accepting this

position. Some time after the commission of the act Sudinna is stricken

with remorse that he had not been able to live to perfection his

monastic life. … He knows and feels that he has erred and brought ruin

upon himself. For he says that he has committed a sinful deed. …

Perhaps it would also have occurred to him that his act was in violation

of the item of sila which refers to the practice of celibacy. …

Sudinna did not know that his act was an offence against the spirit of

Buddhist monasticism. Two things preclude us from accepting this

position. Some time after the commission of the act Sudinna is stricken

with remorse that he had not been able to live to perfection his

monastic life. … He knows and feels that he has erred and brought ruin

upon himself. For he says that he has committed a sinful deed. …

Perhaps it would also have occurred to him that his act was in violation

of the item of sila which refers to the practice of celibacy. …

Therefore we cannot take anadinavadasso to mean that Sudinna did not

know that methunadhamma was an offence against monastic life. Nor does

he claim such ignorance anywhere during the inquiries held by his fellow

celibates or the Buddha. Secondly, even in the absence of any

restrictive regulations it seems to have been very clear to all members

of the Buddhist Sangha that according to what the Buddha had declared in

his Dhamma, the offence of methunadhamma contradicts the spirit of true

renunciation … .”

know that methunadhamma was an offence against monastic life. Nor does

he claim such ignorance anywhere during the inquiries held by his fellow

celibates or the Buddha. Secondly, even in the absence of any

restrictive regulations it seems to have been very clear to all members

of the Buddhist Sangha that according to what the Buddha had declared in

his Dhamma, the offence of methunadhamma contradicts the spirit of true

renunciation … .”

[Dhirasekera. 1981 pp.46-7]

The

admission of Sudinna to the Sangha, as described in the Vinaya, is

quite similar to that of Ratthapala, both being young and wealthy

householders who had to strive to persuade their households to get

permission for admission. It is difficult to believe that Sudinna did

not know about this received view. This point becomes further clear when

we examine the remarks by his fellow celibates on hearing the act

committed by Sudinna:

admission of Sudinna to the Sangha, as described in the Vinaya, is

quite similar to that of Ratthapala, both being young and wealthy

householders who had to strive to persuade their households to get

permission for admission. It is difficult to believe that Sudinna did

not know about this received view. This point becomes further clear when

we examine the remarks by his fellow celibates on hearing the act

committed by Sudinna:

Isn’t it the case that the Buddha has taught the Dhamma in many ways

for detachment and not for attachment; for disengagement and not for

engagement; for non-grasp and not for grasp? … Isn’t it the case that

the Buddha has taught the Dhamma in many ways for detachment of

attachment, for non-intoxication of intoxication, for the control of

thirst, for the destruction of longing, for the cutting of circle, for

the extinction of craving, for detachment, for cessation, for Nibbana

[Vinaya III. pp. 19-20.]

for detachment and not for attachment; for disengagement and not for

engagement; for non-grasp and not for grasp? … Isn’t it the case that

the Buddha has taught the Dhamma in many ways for detachment of

attachment, for non-intoxication of intoxication, for the control of

thirst, for the destruction of longing, for the cutting of circle, for

the extinction of craving, for detachment, for cessation, for Nibbana

[Vinaya III. pp. 19-20.]

These

remarks testify to the fact that celibacy was understood in the

tradition as an essential aspect of monastic life which follows from the

very logic of renunciation, i.e., ending suffering by eradicating the

thirst for pleasures.

remarks testify to the fact that celibacy was understood in the

tradition as an essential aspect of monastic life which follows from the

very logic of renunciation, i.e., ending suffering by eradicating the

thirst for pleasures.

This

intimate connection between monastic life and practice of celibacy

makes clear why a person found guilty of violation of the rule had to be

removed forthwith from the Sangha.

intimate connection between monastic life and practice of celibacy

makes clear why a person found guilty of violation of the rule had to be

removed forthwith from the Sangha.

The

term used to indicate removal from the Sangha is “should be killed”

[naasetabba]. The origin of the metaphorical usage can be seen in the

Buddha’s discussion with the horse-trainer who classifies his methods of

training horses as mild and rough and failing in both, killing. The

Buddha responds to him by saying that he would followthe identical

methods in training his disciples. To the bewildered Horse-trainer as to

how the kind-hearted Buddha could kill any disciple the Buddha explains

that killing in his training his totally giving up and letting him/her

go from the Sangha. Thus “killing” in the context of training is a

metaphor for removing a person from the Sangha.

term used to indicate removal from the Sangha is “should be killed”

[naasetabba]. The origin of the metaphorical usage can be seen in the

Buddha’s discussion with the horse-trainer who classifies his methods of

training horses as mild and rough and failing in both, killing. The

Buddha responds to him by saying that he would followthe identical

methods in training his disciples. To the bewildered Horse-trainer as to

how the kind-hearted Buddha could kill any disciple the Buddha explains

that killing in his training his totally giving up and letting him/her

go from the Sangha. Thus “killing” in the context of training is a

metaphor for removing a person from the Sangha.

The

strong language, however, indicates how the tradition viewed the

situation. It also strongly suggests that the guilty person, who did not

conform to the condition stipulated by: sikkham apaccakkhaya, dubbalyam

anavikatva cannot be reinstated. Once removed from the Sangha how many

people wanted to reenter and how many succeeded are more historical

questions. Unless the particular group of the Sangha knew about the

person there does not seem to have had any other method of knowing the

situation of such a person as a new candidate. It is interesting to note

that among the questions that are asked from a prospective candidates

to judge his/her eligibility this particular question [whether he/she

was guilty of committing parajika offence as a former member of the

Sangha] is not included.

strong language, however, indicates how the tradition viewed the

situation. It also strongly suggests that the guilty person, who did not

conform to the condition stipulated by: sikkham apaccakkhaya, dubbalyam

anavikatva cannot be reinstated. Once removed from the Sangha how many

people wanted to reenter and how many succeeded are more historical

questions. Unless the particular group of the Sangha knew about the

person there does not seem to have had any other method of knowing the

situation of such a person as a new candidate. It is interesting to note

that among the questions that are asked from a prospective candidates

to judge his/her eligibility this particular question [whether he/she

was guilty of committing parajika offence as a former member of the

Sangha] is not included.

“As soon as the King had gone, the Lord said: The King is done for,

his fate is sealed, monks! But if the King had not deprived his father,

that good man and just king, of his life, then as he sat here the pure

and spotless Dhamma-eye would have arisen in him.”[Translation from

Maurice Walshe, 1987. p.109.]

his fate is sealed, monks! But if the King had not deprived his father,

that good man and just king, of his life, then as he sat here the pure

and spotless Dhamma-eye would have arisen in him.”[Translation from

Maurice Walshe, 1987. p.109.]

Looking

from a broader ethical point of view adopted in the Dhamma one could

argue that violation of parajika offence is not strictly a evil action

[papa-kamma], and hence what one loses is only themembership of the

Sangha, which does not mean that he cannot attain magga-phala. In that

sense it is quite different from aanantariya-paapa [an evil action

producing effect in the next birth itself without fail], which, for

example, is believed to have committed by King Ajatasatthu by killing

his father. In the Sammannaphala-sutta the Buddha refers to this action

and says that if it was not for this reason, the King would have

generated “the eye of Dhamma” then and there at his encounter with the

Buddha, but it did not happen for this grave action committed by him.

from a broader ethical point of view adopted in the Dhamma one could

argue that violation of parajika offence is not strictly a evil action

[papa-kamma], and hence what one loses is only themembership of the

Sangha, which does not mean that he cannot attain magga-phala. In that

sense it is quite different from aanantariya-paapa [an evil action

producing effect in the next birth itself without fail], which, for

example, is believed to have committed by King Ajatasatthu by killing

his father. In the Sammannaphala-sutta the Buddha refers to this action

and says that if it was not for this reason, the King would have

generated “the eye of Dhamma” then and there at his encounter with the

Buddha, but it did not happen for this grave action committed by him.

Furthermore,

nowhere has it been said that one will be born in an unpleasant birth

owing to this offence. It could happen if the offender pretends to be a

real bhikkhu/bhikkhuni and continues as one, which involves lying and

hypocrisy. But such a question would not arise for one who forthwith

leaves voluntarily or is removed by the Sangha.

nowhere has it been said that one will be born in an unpleasant birth

owing to this offence. It could happen if the offender pretends to be a

real bhikkhu/bhikkhuni and continues as one, which involves lying and

hypocrisy. But such a question would not arise for one who forthwith

leaves voluntarily or is removed by the Sangha.

Unlike

in the case of an aanantariya-kamma, with violation of parajika offence

one is technically not barred from attaining the goal as taught in the

Dhamma.The parajika offence has to be understood more in the

organizational sense and the punishment for the offence being loss of

the membership of the Sangha.

in the case of an aanantariya-kamma, with violation of parajika offence

one is technically not barred from attaining the goal as taught in the

Dhamma.The parajika offence has to be understood more in the

organizational sense and the punishment for the offence being loss of

the membership of the Sangha.

This,

however, leads to some other questions, for example, on the

significance of being a member [bhikkhu/bhikkhuni] among the sangha. If

it does not make any difference then one must easily be able to continue

as a samanera or householder and still pursue the path.

however, leads to some other questions, for example, on the

significance of being a member [bhikkhu/bhikkhuni] among the sangha. If

it does not make any difference then one must easily be able to continue

as a samanera or householder and still pursue the path.

Although

it is not technically impossible for a non-member of the Sangha to

attain the final goal, such a possibility is not borne by the evidence

we discussed above. While householder with his spouse and children is

bound by the worldly requirements, a samanera is not taken as a member

of the Sangha for it is only a preparatory stage for monkhood.

it is not technically impossible for a non-member of the Sangha to

attain the final goal, such a possibility is not borne by the evidence

we discussed above. While householder with his spouse and children is

bound by the worldly requirements, a samanera is not taken as a member

of the Sangha for it is only a preparatory stage for monkhood.

Since

being a member of the sangha is regarded as the form of life most

conducive for the path of liberation, looking from this point of view,

losing monkhood cannot be regarded as a simple matter of losing the

membership of organization, for having membership makes such a big

difference in the pursuit of the ultimate goal.

being a member of the sangha is regarded as the form of life most

conducive for the path of liberation, looking from this point of view,

losing monkhood cannot be regarded as a simple matter of losing the

membership of organization, for having membership makes such a big

difference in the pursuit of the ultimate goal.

Finally,

there is somewhat a general question to be addressed: does the account

of gratification of senses, articulated in the context of the monastic

vinaya and represented by the first parajika offence, represent the

overall Buddhist attitude to it? If it does then every time an ordinary

non-monastic person engages in sex, or gratification of senses, s/he

must be engaged in something “lowly, uncivilized and out-castely.”

[hiina-dhammo, gaamadhammo vasala-dhammo]

there is somewhat a general question to be addressed: does the account

of gratification of senses, articulated in the context of the monastic

vinaya and represented by the first parajika offence, represent the

overall Buddhist attitude to it? If it does then every time an ordinary

non-monastic person engages in sex, or gratification of senses, s/he

must be engaged in something “lowly, uncivilized and out-castely.”

[hiina-dhammo, gaamadhammo vasala-dhammo]

I

need not produce all the wealth of material contained in such

discourses of the Buddha as Sigalovaada, Vyagghapajja, Vasala, Mangala,

Paraabhava, and many other discourses in order to prove that the Buddha

accepted the validity of the life of householder with its

householder-happiness [gihi-sukha] derived by matrimony, children,

wealth, property; working, doing business, investing, earning and

spending.

need not produce all the wealth of material contained in such

discourses of the Buddha as Sigalovaada, Vyagghapajja, Vasala, Mangala,

Paraabhava, and many other discourses in order to prove that the Buddha

accepted the validity of the life of householder with its

householder-happiness [gihi-sukha] derived by matrimony, children,

wealth, property; working, doing business, investing, earning and

spending.

What

needs to be highlighted, however, is the often not clearly articulated

distinction between goals and purposes of monastic and householder modes

of living. As I mentioned at the very outset of this discussion one is

characterized by total abstinence of kaama [brahmacariya] whereas the

other is characterized by proper kaama [i.e. refraining from wrong

behaviour of kaama= kaamesu-micchaacaara].

needs to be highlighted, however, is the often not clearly articulated