The

Pali Canon is the complete scripture collection of the

Theravada school. As such, it is the only set of scriptures

preserved in the language of its composition. It is

called the Tipitaka

or “Three Baskets” because it includes the

Vinaya Pitaka or “Basket of Discipline,”

the Sutta Pitaka or “Basket of Discourses,”

and the Abhidhamma Pitaka or “Basket of

Higher Teachings”.

http://www.google.co.in/imgres?imgurl=http://www.aimwell.org/Books/a_Cakka.gif&imgrefurl=http://www.aimwell.org/Books/Pesala/Dhammacakka/dhammacakka.html&h=287&w=287&sz=5&tbnid=75xOXKHyGGIJ::&tbnh=115&tbnw=115&prev=/images%3Fq%3DAll%2Bthe%2BSuttas%2Bof%2BVinaya%2BPitaka%2Bwith%2Bpictures&hl=en&usg=__1B-bzV7zRhk3e3cGO6CyrOAntAo=&sa=X&oi=image_result&resnum=2&ct=image&cd=1

http://www.bodhgayanews.net/pali.htm Bhikkhu Pesala

An Exposition of the Dhammacakka Sutta

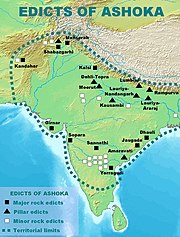

Fragment of the 6th Pillar Edicts of Ashoka (238 BC), in Brahmi, sandstones. British Museum.The Ashoka Chakra, featured on the flag of the Republic of India

Silver punch-mark coins of

the Mauryan empire, bear Buddhist symbols such as the Dharmacakra,

the elephant (previous form of the Buddha), the tree under which

enlightenment happened, and the burial mound where the Buddha died

(obverse). 3rd century BC.

Greek Late Archaic style capital from Patna (Pataliputra), thought to correspond to the reign of Ashoka, 3rd century BC, Patna Museum (click image for references).

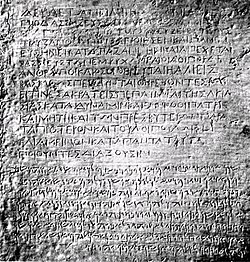

Bilingual edict (Greek and Aramaic) by king Ashoka, from Kandahar - Afghan National Museum. (Click image for translation).Ashoka’s Major Rock Edict inscription at Girnar

Dear All,The attack on the migrant workers from north India by raj

thackeray and his goons is misconceived as attack on north Indians

which it is not. All the people who have been attacked and targeted by

thackeray are Adi-Mulnivasi Bahujans - SCs/STs and OBCs(Original Inhabitants of Jambudvipa,that is, the Great Prabuddha Bharath). If thackeray

wanted to attack the north Indians for stealing the jobs of Marathi

people then he would have first attacked the large number of north

Indians who are working in big corporates, running their own

businesses, working in bollywood, working at higher posts in government

and semi government organizations. But he did nothing of that sort.

Instead the goons of sena and raj thackeray are attackeing the poor and

helpless north Indian SC/ST/OBCs who have come to Mumbai for doing

small time jobs. In fact most of the jobs these poor bahujans from

north India do are not really stolen from the marathi youth. The real

jobs that are stolen from the Marathi Bahujans are actually occupied by

north Indian bramhin(Invaders from Central Asia)-banias(Who have accepted to be the second rate souls after the Invaders from the Central Asia who claim to be the first rate souls).Therefore Raj thackeray is dishonest when he says he is fighting

for marathi youth. Thackeray wants Marathi youth to take up the small

time jobs like rikshawala, milkwala, bhelpuriwala, taxiwala, etc. done

by our bahujan brothers from north India instead of the high profile

jobs done by north Indian bramhin baniyas in Mumbai, this means that

raj thackeray is enemy of Marathi youth and especially Bahujan Marathi

youth. Raj thackeray will never be punished because he is acting in the

interest of bramhin bania parties like congress and bjp.It needs a strong Adi-Mulnivasi Bahujan(Original Inhabitants of Jambudvipa,that is, the Great Prabuddha Bharath) leader ( the Obama of India )

like BSP supremo and UP CM Behen Mayawati to show criminal thackeray

his place in jail.Jayant S. Ramteke

“JAYANT RAMTEKE”

Kannada Language

Kannada is

the state language of Karnataka, one of the four southern states in India. It is also one

of the official languages of theRepublic

ofIndia . It is written

using the Kannada script. Kannada is almost as old as Tamil, the truest of the

Dravidian family.Dravidian language, the

official language of the Indian state of Karnataka. It is spoken by more than

33 million people in Karnataka; an additional 11 million Indians may speak it

as a second language. The earliest inscriptional records in Kannada are from

the 6th century. Kannada script is closely akin to Telugu script in origin.

Like other major Dravidian languages, Kannada has a number of regional and

social dialects and marked distinctions between formal and informal usage.

kannada Channel

History of the Kannada language:

Kannada is a south Indian language spoken in Karnataka state of India.Kannada

is originated from the Dravidian Language. Telugu, Tamil, Malayalam are the

other South Indian Languages originated from Dravidian Language. Kannada and

Telugu have almost the same script. Kannada as a language has undergone

modifications since BCs. It can be classified into four types:

- Purva Halegannada (from the beginning till 10th

Century)- Halegannada (from 10th Century to 12th Century)

- Nadugannada (from 12th Century to 15th Century)

- Hosagannada (from 15th Century)

.

Kannada Channel:

Kannada Channel has links

to various informative websites for News, Magazines,

Kannada Radio, Kannada Portals, Bollywood Movies and Music.Phrases:

Kannada

I Nanu

He Avanu

She Avalu

You Neenu

Mother Thaayi/amma

Father Appa/thandhen

What is your name? Ninna hesarenu?/ Ninna hesaru yenu?

How are you? Hegiddhiya?/ Neenu heghiddhiya?

This Kannada Rajyothsava Day is Special because Classical

Language Status has been declared. Centre grants Classical Language Status to

Telugu, Kannada. All the Original Inhabitants of Jambudvipa, that is, the Great

Prabuddha Bharath all over the world are happy.

EXPLORE THE KANNADA WORLD

More than 2600 years ago, The Exalted, Blessed, Noble and the

Awakened Mighty Great Mind with Full Awareness spoke Prakrit, Brahmi, PaLi for

Peace Welfare and Happiness of all Sentient and Non-Sentient Beings.Sangam period

Amongst the

South Indian Languages, there is written data available for Tamil, Kannada and

Telugu languages.In Kannada, the first shaashana is

the 450 A.D. Halmidi shaashana. Ancient books like Vaddaaraadhane (800),

Kaviraja Marga (850) are also available.450 B.C.

paaNini’s “aShTaadhaayi” has a reference to a “karnaadhaka”

gOtra

250 B.C. King Ashoka’s shaashana

has a reference to name called “isila” which is said to be Kannada

origin.80 B.C. In the

Prakrit shaashana of Madhavpur-Vadagavi, the word “NaaTapati” is a

word of Kannada origin150 A.D. Ancient

Greek historian Ptolemy’s book “Pappyrus” Kannada towns

“kalligere”, “baadaami”, “mudugal” find mention.There is an

abundance of Kannada in many Prakrit shaashanas:a.

Words “nagipa”, “saMkapa” found in the 100 B.C.Prakrit

shaashana have a Kannada formb.

Usage of words like “manaaLi” originates in the union of two Kannada

words “mun” + “paLLi”c.

Kannada towns have been named in constructs like “saMbalIva oora

vaasinO”d.

“mooDaaNa” a word used in different languages to represent the

Eastern direction is of Kannada origin150 A.D. In the Prakrit book “gaathaa saptashati”

written by Haala Raja, Kannada words like “tIr”, “tuppa”,

“peTTu”, “poTTu” have been used.250 A.D. On the Pallava Prakrit

shaashana of Hire Hadagali’s Shivaskandavarman, Kannada word “kOTe”

transforms into “koTTa”250 A.D. In the Tamil mega tome

“shilappadikaaraM” written by Ilango Adi, there is reference to

Kannada in the form of the ! word “karunaaDagar”350 A.D. In the

Chandravalli Prakrit shaasana, words of Kannada origin like

“punaaTa”, “puNaDa” have been used.250 A.D. In one more Prakrit shaasana found in

Malavalli,Kannada towns like “vEgooraM” (bEgooru),

“kundamuchchaMDi” find reference.In the recent 2003 Harvard

publication “Early Tamil Epigraphy” authored by Iravatam Mahadev has

important substance in the current discussion. This publication provides a new

direction and paradigms to the question of Kannada’s antiquity. It extends the

antiquity of Kannada to older times than presently known. It also presents a

new thought that Tamil came under the Kannada influence in the years of B.C.

timeframe. Some Tamil shaasana’s beginning in the 3rd century B.C. shows a

marked Kannada influence.In the 1-3 B.C.

Tamil shaashanas, words of Kannada influence “nalliyooraa”,

kavuDi”, “posil” have been introduced. The use of the vowel

“a” as an adjective is not prevalent in Tamil, its usage is available

in Kannada. Kannada words like “gouDi-gavuDi” transform into Tamil’s

“kavuDi” for lack of the usage of “Ghosha

svana” in Tamil. That is the reason Kannada’s “gavuDi” becomes

“kavuDi” in Tamil. “posil” (Kannada “hosilu”) is

another Kannada word that got added into Tamil. Colloquial Tamil uses this word

as “vaayil“.In the 1 A.D.

Tamil shaasana, there is a personal reference to “ayjayya” which is

of Kannada origin. In another 3 A.D. Tamil shaasana, there is usage of the

words “oppanappa vIran”. The influence of Kannada’s usage of

“appa” to add respect to a person’s name is evident here.

“taayviru” is another word of Kannada influence in another 4 A.D.

Tamil shaasana. We can keep growing this list citing many such examples of

Kannada’s influence on Tamil during the B.C.-A.D. times.Kannada’s

influence on ancient Tamil as depicted by the language of these shaasana’s is

of historical importance. There are no written data available in Kannada from

the times when these Tamil records show a marked Kannada influence. Moreover,

there have been no findings/ discussions of this face of Tamil till now, that

of a deep Kannada influence on it.In the ambit of

the current discussion in the country about “Classical Languages”,

this influence of the influence of Kannada on ancient Tamil is of significance.

In the Central Government’s announcement of “Tamil Language literature is

of antiquity. It has grown independent of the influence of other languages’

literature. This is the reason that Tamil is being accorded the ‘Classical

language’ tag”, these findings have shown the weak foundation on which the

announcement was made. It has also shown the similar antiqueness of Kannada and

the influence it had on Tamil to make it what it is now. These Tamil shaasanas

have extended the horizons of understanding of ancient Karnataka’s language,

and socio-religious culture.The next natural

question is that of the delay of about 500 years between the difference in the

appearance of the Kannada v/s the Tamil written records. These originate in the

political and administrative spheres of those times: the regions of the current

Karnataka and Andhra were then still under the influence of the Mauryas and

Shaatavaahanas, whereas, Tamil regions enjoyed independence of usage in

administration and writing. The Cheras, Cholas, Pantiyas, Satiya Putra

Adiyamanas adopted Tamil. The Jainas,

Buddhist monks adopted the Brahmi font to the Tamil sound/ language.Karanataka and

Andhra were under the Sanskrit deference. Many Prakrit languages were in

circulation since 6 B.C. in the Northern parts ofIndia : The Jains, and Buddhist monks learnt these languages

and wrote and taught in these Prakrit/ Pali languages. In the south, they first adopted, used and taught

in Tamil since there was patronage for that language in the Tamil regions.

There was no opportunity for Kannada to gain such currency under the influence

of the Northern rulers. Such political reasons delayed the emergence of Kannada

into the literal mainstream for about 500 years. Kannada finally started its

independent emergence under the rule of the Kadambas and the Gangas. With such

political and administrative patronage, Kannada literature really blossomed

under the Badami Chalukyas.The summary of

this discussion is enunciated in the following points:1. Kannada came

into its independent existence from the proto-Dravidian language in the 6 B.C.

timeframe.2. In about 3-4

B.C. Kannada was already in use by the common people.3. In 3 B.C.

Kannada influenced the Indo-Aryan languages like Prakrit.4. In the 2-1

B.C. timeframe, Kannada also influenced the Dravidian language Tamil.5. There are

socio-political reasons for the 500 year delay of the emergence of Kannada in

shaasanas when compared to Tamil shaasanas. That does not mean Kannada at that

time did not have its own language, script and literature.6. The reasons

for and against the emergence of Kannada were political: The Banavasi Kadambas

were the first to use Kannada as the second administrative language. Badami

Chalukyas were the first to use Kannada as a primary administrative language

granting it patronage of being the official language and the language of the

state. After that, Kannada has not looked back!Storyof Kannadiga , kannada

and KarnatakaGlimpses of Kannada History and Greatness

Origin

of RastrakutaThe Rashtrakuta Dynasty was a royal Indian dynasty ruling large

parts of southern, central and northernIndia between the sixth and the

thirteenth centuries. During this period they ruled as several closely related,

but individual clans. The earliest known Rashtrakuta inscription is a seventh

century copper plate grant that mentions their rule from Manpur in the Malwa

region of modern Madhya Pradesh. Other ruling Rashtrakuta clans from the same

period mentioned in inscriptions were the kings of Achalapur which is modern

Elichpur inMaharashtra and the rulers of

Kannauj.The clan that ruled from Elichpur was a feudatory of the Badami Chalukyas and

during the rule of Dantidurga, it overthrew Chalukya Kirtivarman II and went on

to build an impressive empire with the Gulbarga region in modern Karnataka as

its base. This clan came to be known as the Rashtrakutas of Manyakheta, rising

to power inSouth India in 753. Period between

the eight and the tenth centuries, saw a tripartite struggle for the resources

of the rich Gangetic plains, each of these three empires annexing the seat of

power at Kannauj for short periods of time. At their peak the Rashtrakutas of

Manyakheta ruled a vast empire stretching from theGanga

River andYamuna

River doab in the north toCape Comorin in the south.During their rule, Jain mathematicians and scholars contributed important works

in Kannada and Sanskrit. Amoghavarsha I was the most famous king of this

dynasty and wrote Kavirajamarga, a landmark literary work in the Kannada

language. The finest examples of which are seen in the Kailasanath Temple at

Ellora and the sculptures of Elephanta Caves in modern Maharashtra as well as

in the Kashivishvanatha temple and the Jain Narayana temple at Pattadakal in

modern Karnataka, all of which are UNESCO World Heritage Sites.The origin of Rashtrakuta dynasty has been a controversial topic. These issues

pertain to the origins of the earliest ancestors of the Rashtrakutas during the

time of Emperor Ashoka in the second century BCE, and the connection between

the several Rashtrakuta dynasties that ruled small kingdoms in northern and

centralIndia and theDeccan between the sixth and seventh centuries. The

relationship of these medieval Rashtrakutas to the most famous later dynasty,

the Rashtrakutas of Manyakheta (present day Malkhed in the Gulbarga district,

Karnataka state), who ruled between the eighth and tenth centuries has also

been debated

Punjab origin

The appearance of the terms Rathika, Ristika (Rashtrika) or Lathika

in conjunction with the

terms Kambhoja and Gandhara in some Ashokan inscriptions of 2nd century BCE

from Mansera and Shahbazgarhi in North Western Frontier Province (present day

Pakisthan), Girnar (Saurashtra) and Dhavali (Kalinga) and the use of the

epithet “Ratta” in many later inscriptions has prompted a claim that

the earliest Rashtrakutas were descendants of the Arattas, natives of the

Punjab region from the time of Mahabharata who later migrated south and set up

kingdoms there, while another theory points more generally to north western

regions of India. Based on this theory, the Arattas may have become natives of

theDeccan having arrived there during the

early centuries of the first millennium. But this is a far fetched theory

having no proof.

Maharastra origin

Term Rishtika used together with Petenika in the Ashokan

inscriptions implied they were hereditary ruling clans from modern Maharashtra

region and the term “Ratta” implied Maharatta ruling families from

modernMaharashtra region. But this has been

rejected on the basis that from ancient books such as Dipavamsha and Mahavamsha

in Pali language it is known the term Maharatta and not Rashtrika has been used

to signify hereditary ruling clans from modern Maharashtra region and the terms

Rashtrika and Petenika appear to be two different displaced ruling tribes.

Marathi or Telugu origin

The argument that the Rashtrakutas were either Marathi speaking

Marathas or Telugu speaking Reddies in origin has been rejected. Reddy’s in

that time period had not come into martial prominence even in the Telugu

speaking regions of Andhra, being largely an agrarian soceity of cultivators

who only much later (in the 14th century - 15th century) came to control

regions in the Krishna - Rajamundry districts. The Rashtrakuta period did not

produce any Marathi inscriptions or literature (with the exception of a 981 CE

Shravanabelagola inscription which some historians argue was inscribed later).

Hence Marathi as the language of the Rashtrakutas, it is claimed, is not an

acceptable argumentRajputs

The Rashtrakutas emerged before the term “Rajput” came to

be used as a community. The emergence of Rajputs in Rajasthan andGujarat coincides with the arrival of the Rashtrakutas

and Chalukyas in the region. So it is just a coincidencekannadiga origin

- Ruling clans called Rathis and

Maharathis were in power in parts of present day Karnataka as well in the

early centuries of the Christian era, which is known inscriptions from the

region and further proven by the discovery of lead coins from the middle

of 3rd century bearing Sadakana Kalalaya Maharathi in the heart of modern

Karnataka region near Chitradurga. In the face of these facts it is

claimed it can no longer be maintained that the Rathi and Maharathi

families were confined only to present dayMaharashtra .

There is sufficient inscriptional evidence that several Maharathi families

were related to Kannadiga families by marriage and they were naga

worshippers, a form of worship very popular in theMysore region.- The epithet Ratta, it is a Kannada

word from which the word Rashtrakuta has been derived. The use of the word

Rattagudlu (meaning an office) has been found in inscriptions from present

day Andhra Pradesh dated prior to the 8th century indicating it was a

South Indian word. From the Deoli plates and Karhad records it is clear

prince called Ratta and his son was called Rashtrakuta. Thus Rashtrakutas

were of Kannada origin. It is also said the term Rashtra means

“kingdom” and Kuta means “lofty” or Rashtra means

state and Kuta means chieftain.- Another epithet used in

inscriptions of Amoghavarsha I was Lattalura Puravaradhiswara. It referes

to their original home Lattalur, modern day Latur inMaharashtra

state, bordering Karnataka. This area was predominantly Kannada speaking

based on surviving vestiges of place names, inscriptions and cultural

relics. So Latta is a Prakrit variation of Ratta and hence Rattana-ur

became Lattana-ur and finally Lattalur.- Connections between the medieval

Rashtrakuta families to the imperial family of Manyakheta, It is clear

that only the family members ruling from Elichpur (Berar or modernAmravati district, modernMaharashtra )

had names that were very similar to the names of Kings of the Manyakheta

dynasty. From the Tivarkhed and Multhai inscriptions it is clear that the

kings of this family were Durgaraja, Govindaraja, Svamikaraja and

Nannaraja. These names closely resemble the names of Manyakheta kings or

their extended family, the name Govindaraja appearing multiple times among

the Manyakheta line. These names also appear in theGujarat

line of Rashtrakutas whose family ties

with the Manyakheta family is well known.- Princes and princesses of the

Rashtrakuta family used pure Kannada names such as Kambarasa, Asagavve,

Revakka and Abbalabbe as their personal names indicating that they were

native Kannadigas. It has been pointed out that princesses of family

lineage belonging toGujarat signed their

royal edicts in Kannada even in their Sanskrit inscriptions. Some examples

of this are the Navsari andBaroda plates

of Karka I and theBaroda

plates of his son Dhruva II. It has been attested by a scholar that theGujarat Rashtrakuta princes signed their

inscriptions in the language of their native home and the race they

belonged to. It is well known that theGujarat

line of Rashtrakutas were from the same family as the Manyakheta line. It

is argued that if the Rashtrakutas were originally a Marathi speaking

family, then the Gujarat Rashtrakutas would not have

signed their inscriptions in Kannada language and that too in far awayGujarat .- While the linguistic leanings of

the early Rashtrakutas has caused considerable debate, the history and

language of the Rashtrakutas of Manyakheta has been free of such

confusion. It is clear from inscriptions, coinage and prolific literature

that the court of these

Rashtrakutas was multi-lingual, used Sanskrit and Kannada as their

administrative languages and encouraged literature in Sanskrit and

Kannada. As such, from the Kavirajamarga of 9th century, it is known that

Kannada was popular from Kaveri

river up to the Godavari river, an area covering large territory in modern

Maharashtra .- The Rashtrakuta inscriptions call

them the vanquishers of the Karnatabala, a sobriquet used to refer to the

near invincibility of the Chalukyas of Badami. This however it should not

be construed to mean that the Rashtrakutas themselves were not Kannadigas.

Their patronage and love of the Kannada language is apparent in that most

of their inscriptions

within modern Karnataka are in Kannada, while their inscriptions outside

of modern Karnataka tended to be in Sanskrit. An inscription in classical

Kannada of King Krishna III has also been found as far away as Jabalpur in

modern Madhya Pradesh which further supports the view of their affinity to

the language kannada.So Rastrakutas are kannadiga origin

NOW is all that You Have

LANGUAGE

The medium of instruction will be English. However if students having read the

material in English would like to answer in Kannada can opt for this also.Mahabodhi

Buddhist Open University! This is an opportunity to study and practice the

noble teachings of the The Exalted, Blessed, Noble

and the Awakened Mighty Great Mind with Full Awareness

to bring happiness and peace in your life apart from development of your

knowledge.

Venerable Acharya Buddharakkhita who

founded the Maha Bodhi Society and its sister organizations and who has been

rendering yeomen services to humanity since 50 years is the founder of this

University. It was his cherished dream to provide a systematic Buddhist

education as widely as possible. MBOU is the result of his efforts and research

in this field. He was a member of the Editorial Board of the Sixth Buddhist

synod (Chattha Sangayana) inRangoon ,

which brought out a complete edition of the Pali Tipitaka. Since then, he has

conducted many Dhamma and Pali courses, meditation courses and written numerous

books and translations of Buddhist texts. They have been published all over the

world, including some German, Portuguese, Korean and Chinese translations. He

has been editing and publishing English monthly magazine DHAMMA for the last

three decades.THE AIMS

1. To conduct Buddhist Study programs through correspondence

courses in a non-formal and cost-effective ways.

2. To prepare candidates for three types of courses and award

diplomas and degrees in Buddhist Studies in an official convocation ceremony on

the Buddha Jayanti day.

3. To present Buddhist teachings in a comprehensive and

practical way. Practice of Buddhist meditation and moral precepts called Panca

sila will be taught as an integral part of these courses

The courses are knowledge and practice oriented and not specifically for

employment. Interested people after completing the course can take up

Dhammacari programs or organize Dhamma study circles.The university is located at the Maha Bodhi Society premises in

Bangalore . A team of

dedicated workers is managing the administration and other departments.THE COURSES

1. DBS – Diploma in Buddhist Studies – Part I, II – 2 years

2. BBS – Bachelor in Buddhist Studies – Part I, II, III – 3

yearsThe academic year will be from June to April the following year. For the year

2006-2007 DBS Part I and BBS Part I will be offered. Then these courses will be

further upgraded year by year.

SELF-INSTRUCTIONAL

MATERIAL

Candidates are supplied with printed materials. Each text book is in

interactive self instructional style and under different heads to facilitate

easy reading and learning.CONTINUOUS EVALUATION THROUGH ASSIGNMENTS

Assignments form an integral part of the university’s system of appraising

candidate’s performance. The students are required to submit the assignments as

per the questionnaire sent to them. The assignments are returned after

evaluation and giving adequate feedback to students. Hence it acts as a

powerful learning device.PRACTICAL SESSIONS

Since practice of meditation is part and parcel of the course candidates should

try to practice at their places. InBangalore

every Sunday mornings meditation and talks are conducted where the candidates

can freely participate.PROJECT WORK

The university insists on candidates to prepare a project report based on their

study and practice in real-life situations as well as experiences based on

research.EXAMINATIONS

At the end of the course annual examination will be conducted over

correspondencePROGRAMME

DELIVERY

The university has adopted a multimedia style of education that comprises

self-learning print material, lessons through internet, personal contact

sessions in a place where there are adequate number of candidates (comprising

lectures, seminars and counseling, audio, visual components etc), practical

sessions, assignments and real life-related /research oriented project work.EVALUATION

Students’ performance is evaluated on a continuous basis - 25% through

assignments and at the term-end 75% through examinations. The minimum

passing marks will be 45 in each paper.

LANGUAGE

The

medium of instruction will be English. However if students having read the

material in English would like to answer in Kannada can opt for this also.

COURSE SYLLABUS

1st year Diploma

Paper 1 -

1. The Buddhahood Ideal

2. The Bodhisatta Ideal and Paramis – Spiritual

Perfections (Jatakas)Paper 2

1. The historical Buddha Gotama – Birth to

EnlightenmentPaper 3

1. The Buddha’s Core Teachings

Paper 1

1. Historical details of the spread of Buddhism till the

final decease of the Buddha – MahaparinibbanaPaper 2

Expansion on the Core Teachings

1. Four noble Truths

2. Noble Eightfold Path

Paper 3

1. Law of Moral Causation

2. Kamma and Rebirth

3. Nature of Nibbana, Enlightenment

2nd Year BA

Paper 1

1. The ideals of the Buddhist Monasticism – Vinaya

2. Monastic Rules of Conduct both for monks and nuns

3. Background stories of rules

4. Rules of conduct for the lay communityPaper 2

1. The relation between Buddhist laity and holy order

2. The six Buddhist Synods and the role of the Holy orderPaper 3

An outline of the Tipitaka

3rd Year BA

Paper 1

1. Analysis of the Dhamma by way of Navanga Buddhasasana,

Navanga Anupubbikatha

2. The Dhamma viewed variously such as Middle Path,

visuddhimaggo, Ekayanamaggo etcPaper 2.

Basic Teachings of the Abhidhamma

1. Two truths

2. Buddhism viewed from the stand points of these truths

3. Paramattha Dhamma

i. Citta

ii. Cetasika

iii. Rupa

iv. Nibbana

4. Buddhist psychology

5. Psychological Ethics and PhilosophyPaper 3

1. Buddhist Social Dimension – Applied Buddhism

2. Buddhist science and human development

3. Buddhist meditation as a psycho therapy and health care

measure

4. Buddhist civilization and culture and their impacts

on human historyApart from the text books provided candidates are advised to read more books.

For information on books please contact Buddha Vacana Trust, 14,Kalidasa Road ,

Gandhinagar, Bangalore-9. Many books are available for sale as well as for free

distribution.

We also advice to subscribe English monthly DHAMMA which carries interesting

articles, published by the Maha Bodhi Society,Bangalore .For more texts on Buddhism please visit:

www.mahabodhi.infoFEES

Admission and Registration fees

DBS courses - Rs.120 per year

BBS courses - Rs.150 per yearThe Course Fees

DBS courses - Rs.500 per year ( US $ 20 for overseas candidates)

BBS courses – Rs.750 per year (US $ 25 for overseas candidates)

The payment should be made by cheque or DD or MO in the name of MAHABODHI

BUDDHIST OPEN UNIVERSITY, Bangalore, payable at Bangalore. or with information

to our office transfer money to our account at

Mahabodhi Buddhist Open University

A/c No.353102010008915

Union Bank ofindia ,

Gandhinagar, Bangalore-560009The last date for the receipt of filled up application form is 30th June 2006.

Address for Correspondence

Mahabodhi Buddhist Open University (MBOU)

14/1, 6th Cross, Gandhinagar, Bangalore-560009

Tel: 080-22250684

Fax: 080-22264438

Email: mbou@mahabodhi.info

Web: www.mahabodhi.info