LESSON 48 BODHISATTVA- 04 -10 -2010 -ONLINE eNālandā Research and Practice UNIVERSITY

You yourself, as much as anybody in the entire universe, deserve your love and affection. - Buddha

WISDOM IS POWER

Awakened One Shows the Path to Attain Ultimate Bliss

Anyone Can Attain Ultimate Bliss Just Visit:http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org

COMPUTER IS AN ENTERTAINMENT INSTRUMENT!

INTERNET!

IS

ENTERTAINMENT NET!

TO BE MOST APPROPRIATE!

Using such an instrument

The Free e-Nālandā Research and Practice University has been re-organized to function through the following Schools of Learning :

Buddha’s Sangha Practiced His Dhamma Free of cost, hence the Free

e-Nālandā Research and Practice University follows suit

As the Original�Nālandā University did not offer any Degree, so also the Free� e-Nālandā Research and Practice University.

The teachings of Buddha are eternal, but even then Buddha did not proclaim them to be infallible. The religion of Buddha has the capacity to change according to times, a quality which no other religion can claim to have…Now what is the basis of Buddhism? If you study carefully, you will see that Buddhism is based on reason. There is an element of flexibility inherent in it, which is not found in any other religion.

§ Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar , Indian scholar, philosopher and architect of Constitution of India, in his writing and speeches

I. KAMMA

REBIRTH

AWAKEN-NESS�

BUDDHA

THUS COME ONE

DHAMMA

II. ARHAT

FOUR HOLY TRUTHS

EIGHTFOLD PATH

TWELVEFOLD CONDITIONED ARISING

BODHISATTVA

PARAMITA

SIX PARAMITAS

III.

SIX SPIRITUAL POWERS

SIX PATHS OF REBIRTH

TEN DHARMA REALMS

FIVE SKANDHAS

EIGHTEEN REALMS

FIVE MORAL PRECEPTS

IV.

MEDITATION

MINDFULNESS

FOUR APPLICATIONS OF MINDFULNESS

LOTUS POSTURE

SAMADHI

CHAN SCHOOL

FOUR JHANAS

FOUR FORMLESS REALMS

V.

FIVE TYPES OF BUDDHIST STUDY AND PRACTICE

MAHAYANA AND HINAYANA COMPARED

PURE LAND

BUDDHA RECITATION

EIGHT CONSCIOUSNESSES

ONE HUNDRED DHARMAS

EMPTINESS

VI.

DEMON

LINEAGE

with

Level I: Introduction to Buddhism

Level II: Buddhist Studies

TO ATTAIN

Level III: Stream-Enterer

Level IV: Once - Returner

Level V: Non-Returner Level VI: Arhat

Jambudvipa, i.e, PraBuddha Bharath scientific thought in

mathematics,

astronomy,

alchemy,

and

anatomy

Philosophy and Comparative Religions;

Historical Studies;

International Relations and Peace Studies;

Business Management in relation to Public Policy and Development Studies;

Languages and Literature;

and Ecology and Environmental Studies

come to the Free Online e-Nālandā Research and Practice University

Course Programs: BODHISATTVA

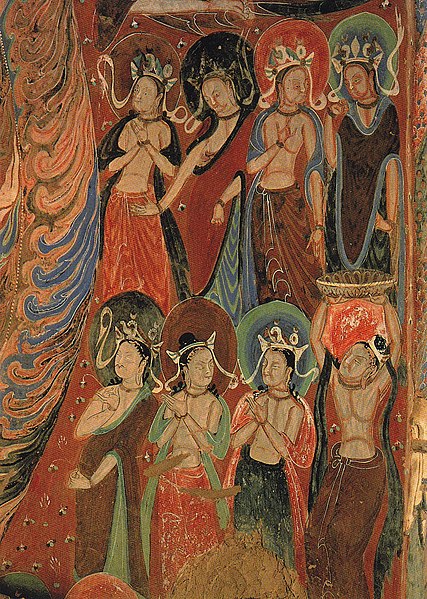

Twenty-five Bodhisattvas Descending from Heaven. Japanese painting, c. 1300.

This article is about Buddhism. For the Steely Dan song, see Countdown to Ecstasy. For the Pradhan poem, see Boddhisattva (poem).

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva (Sanskrit: बोधिसत्त्व bodhisattva; Pali: बोधिसत्त bodhisatta) is either an enlightened (bodhi) existence (sattva) or an enlightenment-being or, given the variant Sanskrit spelling satva rather than sattva, “heroic-minded one (satva) for enlightenment (bodhi).” Another term is “wisdom-being.”[1] It is anyone who, motivated by great compassion, has generated bodhicitta, which is a spontaneous wish to attain Buddhahood for the benefit of all sentient beings.[2]

The bodhisattva is a popular subject in Buddhist art.

In Theravāda Buddhism

The term “bodhisatta” (Pāli language) was used by the Buddha in the Pāli canon to refer to himself both in his previous lives and as a young man in his current life, prior to his enlightenment, in the period during which he was working towards his own liberation. When, during his discourses, he recounts his experiences as a young aspirant, he regularly uses the phrase “When I was an unenlightened bodhisatta…” The term therefore connotes a being who is “bound for enlightenment”, in other words, a person whose aim is to become fully enlightened. In the Pāli canon, the bodhisatta is also described as someone who is still subject to birth, illness, death, sorrow, defilement and delusion. Some of the previous lives of the Buddha as a bodhisattva are featured in the Jātaka tales.

In the Pāli canon, the bodhisatta Siddhartha Gotama is described thus:[3]

before my Awakening, when I was an unawakened bodhisatta, being subject myself to birth, sought what was likewise subject to birth. Being subject myself to aging… illness… death… sorrow… defilement, I sought [happiness in] what was likewise subject to illness… death… sorrow… defilement.

—Ariyapariyesana Sutta

While Maitreya (Pāli: Metteya) is mentioned in the Pāli canon, he is not referred to as a bodhisattva, but simply the next fully awakened Buddha to come into existence long after the current teachings of the Buddha are lost.

In later Theravāda literature, the term “bodhisatta” is used fairly frequently in the sense of someone on the path to liberation. The later tradition of commentary also recognizes the existence of two additional types of bodhisattas: the paccekabodhisatta who will attain Paccekabuddhahood, and the savakabodhisatta who will attain enlightenment as a disciple of a Buddha. According to the Theravāda teacher Bhikkhu Bodhi the bodhisattva path was not taught by Buddha

Theravadin bhikku and scholar Walpola Rahula (Sri Rahula Maha Thera) has stated that the bodhisattva ideal has traditionally been held to be higher than the state of aśrāvaka not only in Mahāyāna, but also in Theravāda Buddhism. He also quotes an inscription from the 10th Century king of Sri Lanka, Mahinda IV (956-972 CE) who had the words inscribed “none but the bodhisattvas would become kings of Sri Lanka”, among other examples.[4]

There is a wide-spread belief, particularly in the West, that the ideal of the Theravada, which they conveniently identify with Hinayana, is to become an Arahant while that of the Mahayana is to become a Bodhisattva and finally to attain the state of a Buddha. It must be categorically stated that this is incorrect. This idea was spread by some early Orientalists at a time when Buddhist studies were beginning in the West, and the others who followed them accepted it without taking the trouble to go into the problem by examining the texts and living traditions in Buddhist countries. But the fact is that both the Theravada and the Mahayana unanimously accept the Bodhisattva ideal as the highest.

—Walpola Rahula, Bodhisattva Ideal in Buddhism

In Mahāyāna Buddhism

Bodhisattva ideal

Mahāyāna Buddhism is based principally upon the path of a bodhisattva. According to Jan Nattier, the term Mahāyāna (”Great Vehicle”) was originally even an honorary synonym forBodhisattvayāna, or the “Bodhisattva Vehicle.”[5] The Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra contains an simple and brief definition for the term bodhisattva, which is also the earliest known Mahāyāna definition.[6][7] This definition is given as the following.[8]

“Because he has enlightenment as his aim, a bodhisattva-mahāsattva is so called.”

Mahāyāna Buddhism encourages everyone to become bodhisattvas and to take the bodhisattva vows. With these vows, one makes the promise to work for the complete enlightenment of all sentient beings by practicing the six perfections.[9] Indelibly entwined with the bodhisattva vow is merit transference (pariṇāmanā).

In Mahāyāna Buddhism life in this world is compared to people living in a house that is on fire. People take this world as reality pursuing worldly projects and pleasures without realising that the house is on fire and will soon burn down (due to the inevitability of death). A bodhisattva is one who has a determination to free sentient beings from samsara and its cycle of death, rebirth and suffering. This type of mind is known as the mind of awakening (bodhicitta). Bodhisattvas take bodhisattva vows in order to progress on the spiritual path towardsbuddhahood.

There are a variety of different conceptions of the nature of a bodhisattva in Mahāyāna. According to some Mahāyāna sources a bodhisattva is someone on the path to full Buddhahood. Others speak of bodhisattvas renouncing Buddhahood. According to the Kun-bzang bla-ma’i zhal-lung, a bodhisattva can choose any of three paths to help sentient beings in the process of achieving buddhahood. They are:

- king-like bodhisattva - one who aspires to become buddha as soon as possible and then help sentient beings in full fledge;

- boatman-like bodhisattva - one who aspires to achieve buddhahood along with other sentient beings and

- shepherd-like bodhisattva - one who aspires to delay buddhahood until all other sentient beings achieve buddhahood. Bodhisattvas like Avalokiteśvara and Śāntideva are believed to fall in this category.

According to the doctrine of some Tibetan schools (like Theravāda but for different reasons), only the first of these is recognized. It is held that Buddhas remain in the world, able to help others, so there is no point in delay. Geshe Kelsang Gyatso notes:[10]

In reality, the second two types of bodhicitta are wishes that are impossible to fulfill because it is only possible to lead others to enlightenment once we have attained enlightenment ourself. Therefore, only king-like bodhicitta is actual bodhicitta. Je Tsongkhapa says that although the other Bodhisattvas wish for that which is impossible, their attitude is sublime and unmistaken.

The Nyingma school, however, holds that the lowest level is the way of the king, who primarily seeks his own benefit but who recognizes that his benefit depends crucially on that of his kingdom and his subjects. The middle level is the path of the boatman, who ferries his passengers across the river and simultaneously, of course, ferries himself as well. The highest level is that of the shepherd, who makes sure that all his sheep arrive safely ahead of him and places their welfare above his own.[11]

Ten grounds

According to many traditions within Mahāyāna Buddhism, on the way to becoming a Buddha, a bodhisattva proceeds through ten, or sometimes fourteen, grounds or bhūmis. Below is the list of the ten bhūmis and their descriptions according to the Avataṃsaka Sūtra and The Jewel Ornament of Liberation, a treatise by Gampopa, an influential teacher of the Tibetan Kagyuschool. (Other schools give slightly variant descriptions.)

Before a bodhisattva arrives at the first ground, he or she first must travel the first two of the five paths:

- the path of accumulation

- the path of preparation

The ten grounds of the bodhisattva then can be grouped into the next three paths

- bhūmi 1 the path of insight

- bhūmis 2-7 the path of meditation

- bhūmis 8-10 the path of no more learning

The chapter of ten grounds in the Avataṃsaka Sūtra refers to 52 stages. The 10 grounds are:

- Great Joy: It is said that being close to enlightenment and seeing the benefit for all sentient beings, one achieves great joy, hence the name. In this bhūmi the bodhisattvas practice all perfections (pāramitās), but especially emphasizing generosity (dāna).

- Stainless: In accomplishing the second bhūmi, the bodhisattva is free from the stains of immorality, therefore, this bhūmi is named “stainless”. The emphasized perfection is moral discipline (śīla).

- Luminous: The third bhūmi is named “luminous”, because, for a bodhisattva who accomplishes this bhūmi, the light of Dharma is said to radiate for others from the bodhisattva. The emphasized perfection is patience (kṣānti).

- Radiant: This bhūmi is called “radiant”, because it is said to be like a radiating light that fully burns that which opposes enlightenment. The emphasized perfection is vigor(vīrya).

- Very difficult to train: Bodhisattvas who attain this bhūmi strive to help sentient beings attain maturity, and do not become emotionally involved when such beings respond negatively, both of which are difficult to do. The emphasized perfection is meditative concentration (dhyāna).

- Obviously Transcendent: By depending on the perfection of wisdom, [the bodhisattva] does not abide in either saṃsāra or nirvāṇa, so this state is “obviously transcendent”. The emphasized perfection is wisdom (prajñā).

- Gone afar: Particular emphasis is on the perfection of skilful means (upāya), to help others.

- Immovable: The emphasized virtue is aspiration. This, the “immovable” bhūmi, is the bhūmi at which one becomes able to choose his place of rebirth.

- Good Discriminating Wisdom: The emphasized virtue is power.

- Cloud of Dharma: The emphasized virtue is the practice of primordial wisdom.

After the ten bhūmis, according to Mahāyāna Buddhism, one attains complete enlightenment and becomes a Buddha.

With the 52 stages, the Śūraṅgama Sūtra in East Asia recognizes 57 stages. With the 10 grounds, various Vajrayāna schools recognize 3–10 additional grounds,[12] mostly 6 more grounds with variant descriptions.[13]

A bodhisattva above the 7th ground is called a mahāsattva. Some bodhisattvas such as Samantabhadra are also said to have already attained buddhahood.[14]

School doctrines

Some sutras said a beginner would take 3–22 countless eons (mahāsaṃkhyeya kalpas) to become a buddha.[15][16][17] Pure Land Buddhism suggests buddhists go to the pure lands to practice. Tiantai, Huayan, Zen and Vajrayāna schools say they teach ways to attain buddhahood within one karmic cycle.[18][19]

Various traditions within Buddhism believe in specific bodhisattvas. Some bodhisattvas appear across traditions, but due to language barriers may be seen as separate entities. For example, Tibetan Buddhists believe in various forms of Chenrezig, who is Avalokiteśvara in Sanskrit, Guanyin (Kwan-yin or Kuan-yin) in China and Korea, Quan Am in Vietnam, and Kannon (formerly spelled and pronounced: Kwannon) in Japan. Followers of Tibetan Buddhism consider the Dalai Lamas and the Karmapas to be an emanation of Chenrezig, the Bodhisattva of Compassion.

Kṣitigarbha is another popular bodhisattva in Japan and China. He is known for aiding those who are lost. His greatest compassionate vow is:

If I do not go to the hell to help the suffering beings there, who else will go? … if the hells are not empty I will not become a Buddha. Only when all living beings have been saved, will I attain Bodhi.

The place of a bodhisattva’s earthly deeds, such as the achievement of enlightenment or the acts of dharma, is known as a bodhimanda, and may be a site of pilgrimage. Many temples and monasteries are famous as bodhimandas; for instance, the island of Putuoshan, located off the coast of Ningbo, is venerated by Chinese Buddhists as thebodhimanda of Avalokiteśvara. Perhaps the most famous bodhimanda of all is the bodhi tree under which Śākyamuṇi achieved buddhahood.]

Siddhartha Gautama as a bodhisattva. Gandhāra, 2nd-3rd century

In reality, the second two types of bodhicitta are wishes that are impossible to fulfill because it is only possible to lead others to enlightenment once we have attained enlightenment ourself. Therefore, only king-like bodhicitta is actual bodhicitta. Je Tsongkhapa says that although the other Bodhisattvas wish for that which is impossible, their attitude is sublime and unmistaken.

If I do not go to the hell to help the suffering beings there, who else will go? … if the hells are not empty I will not become a Buddha. Only when all living beings have been saved, will I attain Bodhi.

Standing bodhisattva. Gandhāra, 2nd-3rd century

Gathering of bodhisattvas. China, 6th century.

Mural of bodhisattvas. China, Tang Dynasty.

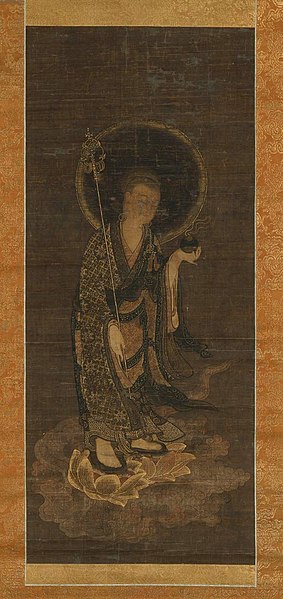

Ākāśagarbha Bodhisattva. Japan, 9th century.

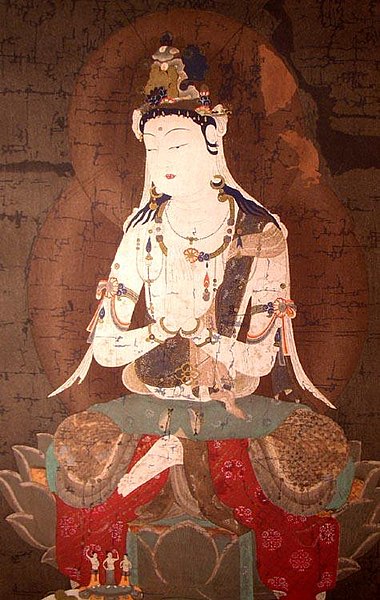

Mural of a bodhisattva. China, 10th century.

AvalokiteśvaraBodhisattva. India, 11th-12th century.

MahāsthāmaprāptaBodhisattva. China, 13th century.

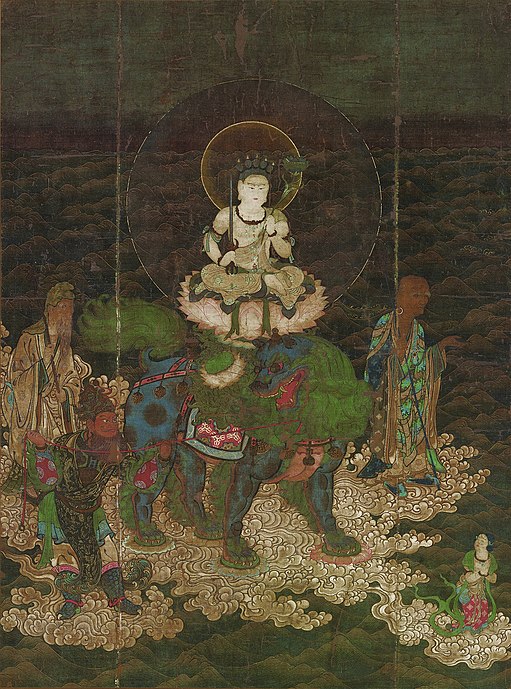

Mañjuśrī Bodhisattva crossing the sea. Japan, 14th century.

Kṣitigarbha Bodhisattva. Japan, 15th century.

SamantabhadraBodhisattva. Japan

Maitreya Bodhisattva. Tibet.