20 04 2012 FRDAY LESSON

587 FREE ONLINE eNālāndā Research And Practice UNIVERSITY And THE BUDDHIST ONLINE GOOD NEWS LETTER by AWAKEN ONE WITH AWARENESS ABHIDHAMMA RAKKHITA through http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org

Sarvajan.ambedkar.org - Vote BSP Elephant for

Change

million domains). This site is relatively popular among users in the India. It gets 87.6% from India.

This site is estimated worth $3,336USD.

This site has a good Pagerank(4/10). It has 473 backlinks. It’s good for seo

website. Sarvajan.ambedkar.org has 17%

seo score. Sarvajan.ambedkar.org is safe and can be available by children,

contains no malicious software and is not used for phishing.

sarvajan.ambedkar.org

domain report about sarvajan.ambedkar.org. According to our report this website

is hosted on IP 66.113.136.199. At this present time sarvajan.ambedkar.org has

a Google Pagerank of 6. sarvajan.ambedkar.org is a website with traffic ranking

of 380,141

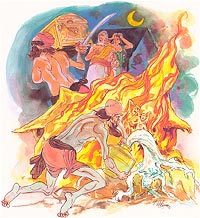

The Holy Is Disastrous

Dhammapada Verse 140 Woeful States In

The Wake Of Evil Doing

Verse

140. Woeful States In The Wake Of Evil Doing

Or one’s houses burn

on raging conflagration,

at the body’s end, in hell

arises that unwise one.

Explanation: Or else, his houses will be burnt by fire and, upon

death, that person will be reborn in hell.

IV.

MEDITATION

MINDFULNESS

FOUR APPLICATIONS OF MINDFULNESS

LOTUS POSTURE

SAMADHI

CHAN SCHOOL

FOUR

DHYANAS

FOUR FORMLESS REALMS

LOTUS POSTURE

Mayawati

or Hatshepsut: Her place has to be shown

Posted: 19 April

2012 By: anu

A handbag. A false beard.

Two seemingly innocuous objects which transform into

fearsome symbols, when they adorn the statues of Mayawati and Hatshepsut

respectively. These women statues have unleashed unprecedented amounts of

societal outrage. Is the cause for outrage the engravings themselves, or the

depicted demeanor, or is it the act of consecrating one’s own statue? The

answer would be all three reasons and more. The intensity of the backlash

alludes to the kind of transgressive power that Mayawati and Hatshepsut have

come to signify.

Several centuries separate these two women. One has an

oppressed heritage, the other was a royal. Both aspired for, obtained and

commanded power in the political arena. And both stood in opposition to known

ways of handling political power. Compelling parallels can be traced in the

stories of their power management, the most obvious one is that they went on to

mark their uniqueness in stone, for posterity. To focus on any one aspect of their

lives would be a dishonor to these two remarkable women. Here, I am contexting

the reaction to their statues for a precise purpose, that is, to illustrate two

forms of oppression: patriarchy and caste, and how they function in relation to

woman power.

Hatshepsut is among other things, a historical marker for

rupturing patriarchal supremacy, and likewise Mayawati is a contemporary marker

for cracking open the mantle of caste supremacy.

Caste is a tightly woven mesh of many oppressions,

including that of gender. Caste as a complex system of oppressive powers has

its origin and practice located exclusively in South Asia, and it can rarely be

illuminated effectively with idioms and metaphors from elsewhere. To understand

how oppression operates and to contest it, the anti-caste discourse draws

widely from the articulation of marginalized communities from all over the

world. But it aims to look for meanings, definitions and examples from within

the caste universe. Though separated by time, space and cultures, I still

chose Hatshepsut because the sub-context here is iconography as a memory-making

device for women’s history, and in this regard the parallel between these

two women is obvious. As John Berger, the art critic said;

“It’s as though across time, images, I mean it sounds

strange to say it, but images recognize each other. Or pay tribute to each

other” .

I am a science researcher and my profession shelters my

introverted nature. It suits the majority of scientists to not be visible as

persons and allow only their work to speak. Does this mean I am limited in my

appreciation of career choices that place women squarely in the public sphere

and the demands thereof? Unlike science, low visibility is not part of the

reward system for politicians. I am impressed that they work and deliver under

high visibility; I am also curiously fascinated that they are also the chief

arbiters of long term memory-making expenditure. In other words, the power to

execute secular iconography (including that of science) is part of their

profession’s power perks; they may ignore this aspect or dedicate energy to it.

(Ambedkar memorial park, Lucknow)

The architectural palettes of Hatshepsut and Mayawati were

vast, in the latter’s case they include hospitals, memorials, highways, sports

complexes, rural infrastructure and city enhancements but the elites direct

their ire mainly towards the personal statues. This in turn points towards

other structures; caste and patriarchy. That power should never have been in

the possession of these two women can be grasped from the huge amounts of

anxiety their statues produced, documented as furious words and destructive actions.

The idea here is not to simply connect these two women leader’s personalities,

or study the way they governed, but to examine what they both famously inspired

–revulsion, mammoth anger, the collective fear and outrage of the powers they

had displaced briefly, in their respective societies.

This takes us squarely to our understanding of iconography

as a means of perpetuating old orders. Representation of women as markers of

power, as agents of change or as knowledge producers is rarely encountered in

the iconography of patriarchal societies. Do we wonder about this? How many

women have challenged this primary means of long term memory-making in human

history? Or should we say memory-making processes in patriarchal history!

Did other queens rule as kings before Hatshepsut? Her

reign is not just a historical aberration- a sudden interruption in the

succession of male Pharaohs, but it is a record of what that change could imply

at the political level for the history of patriarchy. Because her rule did not

simply follow the blueprint laid out by her male predecessors but sharply

deviated from it. Her vision was not war and occupation, but trade and

prosperity, and her legacy, societal peace and architectural magnificence.

Legend goes that she effortlessly defanged patriarchy’s chief political

machinery, the military. Restlessness of the elites automatically followed.

Hatshepsut thus was an agent of change who deserved hatred from them, potent

enough to warrant her disappearance from the evidential records of history.

(Deir el Bahri, Egypt)

Long after her reign, her story was pieced together from

statues, images and inscriptions. All of them disfigured to some extent by her

male successors.

Egyptian female king, Hatshepsut, died, images and

inscriptions which recognized her as a king were defaced or destroyed. This

began the long process of forgetting that Egypt had had a woman who ruled as a

king. Female images of Hatsheput were also destroyed especially if they were

connected with her power or title as king.

Yet she lives on, her memory tantalizes us with alternate

possibilities of how societies may be governed under female leadership, under

truly radical women leaders.

A note in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

describes Hatshepsut’s statues thus:

“In her temple at Deir el-Bahri there were at least

ten over-life-sized kneeling statues of Hatshepsut.”

Does one imagine that someone else built it for her, after

her death? They were built during her reign. This ought to gently wake

up the critics of Mayawati’s statues, and there are many learned ones

-historians, feminists, opinion makers of all hues who go to town about her

megalomaniac acts in stone. They have very public and frantic spiritual

convulsions exclaiming ‘how can you build your own statues during your own

lifetime?’ They all seem to be in a deep slumber about radical women’s

histories elsewhere.

Criticism of Mayawati’s ‘blasphemous’ act of consecrating

her own statues as a part of the pantheon of Dalit icons, always attempts to

separate it from the singular power she alone wielded to halt one of the

world’s biggest invisibilising projects- erasure of the evidence of anti-caste

struggles. I must emphasize again, she alone commanded the power to give the

world the iconography of the centuries old anti-caste movements. Can one

imagine America without the positive iconography of the civil rights movement

and its leaders? The anti-caste movement has been fighting a much older battle

for human and civil rights of adivasis and dalitbhaujan for so many centuries

now. It is imperative for the dominant caste elites to keep this completely

hidden; the force of their need to retain the caste order far outweighs all the

oppressive power of white America’s racism. Now, Mayawati’s architectural

investments have blown the cover for good. A simple logic visually unfolds

itself to the world; to acknowledge the anti-caste movements and its leaders is

to acknowledge caste. To vilify the person who took up this massive corrective

to historical misrepresentation is but natural. Those monuments, those statues

are not just the heritage of the anti-caste movements, but they are in fact an

exposition of India’s moral, political and spiritual pretensions of being a

democratic, secular nation with a glorious past. It sculpts for the world–

caste. It delineates in tangible form the caste history of India. When the

struggle against caste is cast in stone, caste can no longer be a vaguely

explained abstraction to be restricted to little academic books and exclusive

conferences. Caste is now on the physical landscape, forcing national and

international conversations about how India functions as a society. It informs

one and all that the basic element of human interaction of people in the

subcontinent is the complete and abiding faith in the inequality of humans.

Racism is a term that is extremely inadequate to describe this form of human

behavior.

The budget for the monuments in Uttar Pradesh went through

the usual procedures of obtaining approval from the cabinet. If people in U.P

thought it was an outrageous, unwarranted expense it could have triggered mass

protests on the streets, it was not a project that happened in a clandestine

manner, it was out there for public scrutiny at all stages. Dalit intellectuals

and writers have ripped apart the false concern about misuse of public money–

they simply want to know who foots the bill for all the iconography of the

political leaders and movements of the dominant castes? The basic fact is that

the BSP’s monument building projects could have been stopped at any time, if it

had violated any known law.

So who is outraged? The brahmanical elites with access to

TV studios and mainstream media. The same ones who are gleeful about public

money being squandered on ephemeral mega shows like the commonwealth games.

Then what is their outrage about? Is it directed against

gender or is it against caste?

How much of this overlaps with the outrage meted out to

Hatshepsut’s reign and statues and how much of it overlaps with the need to

continue the invisiblizing of the anti-caste struggles? What does it tell us

about how caste, patriarchy and class operate?

The outcry from the elites is to hanker after Mayawati’s

statues like it is a single mutation that needs quick elimination to restore us

back to a world of infinitely powerless dalit men and women.

They seem to say: She is a dalit woman, she ought to

reveal and bear the burden of the material deprivation of the most disempowered

person, at all times, even if the ‘miracle of democracy’ elected her as the

chief minister of a state as big as a country like Brazil. Her place has to

be shown.

The ‘war of words’ of the elite in the media is typical of

the method by which brahmanism or caste is kept alive and functional from the

very top of the caste order. They will not wield the sledgehammers themselves.

Vandalism will surely happen in the not too distant future. This will be followed

by theorization from the same elite’s brethren in the academia about lower

castes vs. dalits which results in the destruction of anti-caste monuments in

U.P.

This outrage is not only the moral high-ground occupied by

the elites but is in fact the fearful acknowledgment that not so often in human

history do we come across a woman with the power to command the engraving of

her own image in stone, which has the approval of an elected government. Here

is a dalit woman who did just that. Unlike most of the female statues scattered

around the world, from past to present times, neither are her statues tailored

to the male gaze nor are they signposts of male benevolence, these represent

her sense of history and were built to her own specifications. So there! Go on,

bring in the sledge hammers.

But just pause to think about what it is that one would

like to deface and destroy, the woman or her caste?

To be

continued.

Sources: 1) Women Rulers Throughout the Ages, Guida Myrl jackson-Laufer

2) Twice born riot against democracy, Gail Omvedt.

3) Inscription at Rashtriya Dalit Prerna Sthal

Images courtesy of Bhanu

Pratap Singh and the Internet.

Anu Ramdas is a computational biologist and

a volunteer at

Roundtable India and Savari.