29 04 2012 SUNDAY LESSON 595 FREE ONLINE eNālāndā

Research And Practice UNIVERSITY And

THE BUDDHISTONLINE GOOD NEWS LETTER by ABHIDHAMMA RAKKHITA through http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org

Dhammapada: Verses and Stories

Dhammapada

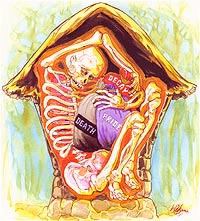

Verse 150 The Body Is A City Of

Bones

Verse

150. The Body Is A City Of Bones

This city’s made of bones

plastered with flesh and blood,

within are stored decay and death,

besmearing and conceit.

Explanation: This body is made of bones which form its

structure. This bare structure is plastered and filled with flesh and blood.

Inside this citadel are deposited decay, death, pride and ingratitude.

V.

FIVE TYPES OF BUDDHIST STUDY AND PRACTICE

MAHAYANA AND HINAYANA COMPARED

PURE LAND

BUDDHA RECITATION

EIGHT CONSCIOUSNESSES

ONE HUNDRED DHARMAS

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eight_Consciousnesses

Eight

Consciousnesses

The

Eight Consciousnesses is a

classification developed in the tradition of the Yogacara school of Buddhism. They enumerate the five senses, supplemented by the mind , the “obscuration” of the mind (manas), and finally

the fundamental store-house

consciousness, which is the basis of the other seven.

|

Contents Consciousness Transformations of consciousness Understanding in Buddhist Tradition Korea also References External links |

Etymology

The Sanskrit term for the Eight

Consciousnesses is Aṣṭavijñāna, from aṣṭa “eight”

and vijñāna “consciousness”. The Tibetan term is rnam-shes

tshogs-brgyad)[1]

The Sanskrit term for store-house consciousness is ālayavijñāna,

from ālaya “abode, dwelling”; Tibetan: kun gzhi rnam shes; Chinese: 阿賴耶識, Japanese: arayashiki (阿頼耶識?)

The Eight

Consciousnesses (Aṣṭa

Vijñāna)

All

Eight Consciousness are “aggregates” or skandha.

The

first six are the sensate “consciousnesses” plus the mind. The Yogacara School that espoused the Cittamatra

Doctrine

proffer two more consciousnesses:

- Eye-consciousnes (Tibetan: mig-gi

rnam-shes), seeing apprehended by the visual sense organs; - Ear-consciousness (Tibetan: rna’i

rnam-shes), hearing apprehended by the auditory sense organs; - Nose-consciousness (Tibetan: sna’i

rnam-shes), smelling apprehended through the olfactory organs; - Tongue-consciousness (Tibetan: lce’i

rnam-shes), tasting perceived through the gustatory organs; - Body-consciousness (Tibetan: lus-kyi

rnam-shes), tactile feeling apprehended through skin contact,

touch. - Ideation-consciousnes (Tibetan: yid-kyi

rnam-shes), the aspect of mind known in Sanskrit as citta or manovijñāna,

the “mind

monkey“;

the consciousness of ideation. - Manas

consciousness

(Sanskrit: klistamanas = klesha; Tibetan: nyon-yid

rnam-shes), obscuration-consciousness (”obscuration”,

“poison”, “enemy”; manas “ideation”,

“moving mind”, “mind monkey”), the consciousness which

through apprehension, gathers the hindrances, the poisons, the karmic

formations; - “Store-house

consciousness” (Sanskrit: ālāyavijñāna; Tibetan: kun-gzhi

rnam-shes), The seed consciousness (bi^ja-vijn~a^na), “the

consciousness which is the basis of the other seven”.[2] It is the

aggregate which administers and yields rebirth.[a]

Origins

and development

Pali Canon

The first five sense-consciousnesses along with the sixth

consciousness are identified in the Sutta Pitaka, especially the Salayatana Vagga subsection of the Samyutta Nikaya:

“Monks, I

will teach you the All. Listen & pay close attention. I will speak.”

“As you say, lord,” the monks responded.

The Blessed One

said, “What is the All? Simply the eye & forms, ear & sounds, nose

& aromas, tongue & flavors, body & tactile sensations, intellect

& ideas. This, monks, is called the All. [1] Anyone who would say,

‘Repudiating this All, I will describe another,’ if questioned on what exactly

might be the grounds for his statement, would be unable to explain, and

furthermore, would be put to grief. Why? Because it lies beyond range.”[3]

Yogacara

Main article: Yogacara

The Yogacara-school gives a detailed explanation of the

workings of the mind and the way it constructs the reality we experience. It is

“meant to be an explanation of experience, rather than a system of

ontology”.[4] Vasubandhu is considered to be

the sytematizer of Yogacara-thought.[5] Vasubandhu used the

concept of the six consciousnesses, on which he elaborated in the Triṃśikaikā-kārikā (Treatise in Thirty

Stanzas).[6]

Consciousness

According

to the traditional interpretation, Vasubandhu states that there are eight

consciousnesses:

- Five

sense-consciousnesses, - Mind

(perception), - Manas

(self-consciousness)[7], - Storehouse-consciousness.[8]

According

to Kalupahana, this classification of eight consciousnesses is based on a

misunderstanding of Vasubandhu’s Triṃśikaikā-kārikā by later

adherents.[9][b]

Aālayavijñāna

The ālaya-vijñāna forms the “base-consciousness”

(mūla-vijñāna) or “causal consciousness”. According to the

traditional interpretation, the other seven consciousnesses are

“evolving” or “transforming” consciousnesses originating in

this base-consciousness.

The store-house consciousness accumulates all potential

energy for the mental (nama) and physical (rupa) manifestation of

one’s existence (namarupa).

It is the storehouse-consciousness which induces transmigration or rebirth,

causing the origination of a new existence

Rebirth and purification

The store-house consciousness receives impressions from

all functions of the other consciousnesses, and retains them as potential

energy, bija or

“seeds”, for their further manifestations and activities. Since it

serves as the container for all experiential impressions it is also called the

“seed consciousness” (種子識) or container consciousness.

According to Yogacara teachings, the

seeds stored in the store consciousness of sentient beings are not pure.[c]

The store consciousness, while being originally immaculate

in itself, contains a “mysterious mixture of purity and defilement, good

and evil”. Because of this mixture the transformation of consciousness

from defilement to purity can take place and awakening is possible.[10]

Through the process of purification the dharma

practitioner can became a Arahat, when the four defilements of the mental

functions [d] of the

manas-consciousness are purified.[e] [f]

Tathagata-garbha thought

According to the Lankavatara Sutra and the schools of Chan/Zen Buddhism, the alaya-vjnana is

identical with the tathagata-garbha[g], and is

fundamentally pure.[11]

The equation of alaya-vjnana and tathagatagarbha was

contested. It was seen as “something akin to the Hindu notions of ātman

(permanent, invariant self) and prakṛti (primordial

substrative nature from which all mental, emotional and physical things

evolve).[12] The critique led by

the end of the eighth centuryto the rise of …

[T]he

logico-epistemic tradition [of Yogācāra] and […] a hybrid school that

combined basic Yogācāra doctrines with Tathāgatagarbha thought.

The logico-epistemological wing in part side-stepped the

critique by using the term citta-santāna, “mind-stream”,

instead of ālaya-vijñāna, for what amounted to roughly the same idea. It

was easier to deny that a “stream” represented a reified self.

On the other

hand, the Tathāgatagarbha hybrid school was no stranger to the charge of

smuggling notions of selfhood into its doctrines, since, for example, it

explicitly defined the tathāgatagarbha as “permanent, pleasurable, self,

and pure (nitya, sukha, ātman, śuddha). Many

Tathāgatagarbha texts, in fact, argue for the acceptance of selfhood (ātman)

as a sign of higher accomplishment. The hybrid school attempted to conflate tathāgatagarbha

with the ālaya-vijñāna.[12]

Transformations of consciousness

The traditional interpretation of the eight

consciousnesses may be discarded on the ground of a reinterpretation of

Vasubandhu’s works.

According to scholar Roger R. Jackson, a

“‘fundamental unconstructed awareness’ (mūla-nirvikalpa-jñāna)”

is “described […] frequently in Yogacara literature.”[13] , Vasubandhu’s work

According to Kalupahana, instead of positing additional

consciousnesses, the Triṃśikaikā-kārikā describes the transformations

of this consciousness:

Taking vipaka,

manana and vijnapti as three different kinds of functions, rather

than caharacteristics, and understanding vijnana itself as a function (vijnanatiti

vijnanam), Vasubandhu seems to be avoiding any form of substantialist

thinking in relation to consciousness.[14]

These transformations are threefold:[14]

Whatever, indeed,

is the variety of ideas of self and elements that prevails, it occurs in the

transformation of consciousness. Such transformation is threefold, [namely,][15]

The first transformation results in the alaya:

the resultant,

what is called mentation, as well as the concept of the object. Herein, the

consciousness called alaya, with all its seeds, is the resultant.[16]

The alaya-vijnana therefore is not an eight consciousness,

but the resultant of the transformation of consciousness:

Instead of being

a completely distinct category, alaya-vijnana merely represents the

normal flow of the stream of consciousness uninterrupted by the appearance of

reflective self-awareness. It is no more than the unbroken stream of

consciousness called the life-proces by the Buddha. It is the cognitive

process, containing both emotive and conative aspects of human experience, but

without the enlarged egoistic ermotions and dognatic graspings characteristic

of the next two transformations.[9]

The second transformation is manana,

self-consciousness or “Self-view, self-confusion, self-esteem and

self-love”.[17] According to the

Lankavatara and later interpreters it is the seventh consciousness.[18] It is

“thinking” about the various perceptions occurring in the stream of

consciousness”.[18] The alaya is

defiled by this self-interest;

[I]t can be

purified by adopting a non-substantialist (anatman) perspective and

thereby allowing the alaya-part (i.e. attachment) to dissipate, leaving

consciousness or the function of being intact.[17]

The third transformation is visaya-vijnapti, the

“concept of the object”.[19] In this

transformation the concept of objects is created. By creating these

concepts human beings become “susceptible to grasping after the

object”:[19]

Vasubandhu is

critical of the third transformation, not because it relates to the conception

of an object, but because it generates grasping after a “real object”

(sad artha), even when it is no more than a conception (vijnapti)

that combines experinece and reflection.[20]

A similar perspective is give by Walpola Rahula. According to Walpola Rahula, all the elements of the Yogācāra

storehouse-consciousness are already found in the Pāli Canon.[21] He writes that the

three layers of the mind (citta, manas, and vijñana) as

presented by Asaṅga are also mentioned in the Pāli

Canon:

Thus we can see

that ‘Vijñāna’ represents the simple reaction or response of the sense organs

when they come in contact with external objects. This is the uppermost or superficial

aspect or layer of the ‘Vijñāna-skandha‘. ‘Manas’ represents the aspect of its mental

functioning, thinking, reasoning, conceiving ideas, etc. ‘Citta’ which is here

called ‘Ālayavijñāna’, represents the deepest, finest and subtlest aspect or

layer of the Aggregate of consciousness. It contains all the traces or

impressions of the past actions and all good and bad future possibilities.[22]

Understanding

in Buddhist Tradition

China

Fa Hsiang and Hua Yen

Although Vasubandhu had postulated

numerous ālaya-vijñāna-s, a separate one for each individual person in the

para-kalpita, this multiplicity was later eliminated in the Fa

Hsiang and Hua Yen metaphysics. These

schools inculcated instead the doctrine of a single universal and eternal

ālaya-vijñāna. This exalted enstatement of the ālaya-vijñāna is described in

the Fa Hsiang as “primordial unity”[23].

The presentation of the three natures by Vasubandhu is

consistent with the Neo-platonist views of Plotinus and his universal

‘One’, ‘Mind’, and ‘Soul’.[24]

Chán

A core teaching of Chan/Zen Buddhism describes the

transformation of the Eight Consciousnesses into the Four Wisdoms.[h] In this teaching,

Buddhist practice is to turn the light of awareness around, from misconceptions

regarding the nature of reality as being external, to directly see one’s own nature. Thus the Eighth Consciousness is transformed into the Great Perfect

Mirror Wisdom, the Seventh Consciousness into the Equality (Universal Nature)

Wisdom, the Sixth Consciousness into the Profound Observing Wisdom, and First

to Fifth Consciousnesses into the All Performing (Perfection of Action) Wisdom.

See also

- Brahmavihara

- Doctrine

of Consciousness-Only - Mindstream

- Thirty Verses on Consciousness-only

- Three

kinds of objects - Anatta

in the Tathagatagarbha Sutras

Notes

1.

^ This idea may in some

respects be compared to the usage of the word “citta” in the agamas. In the early texts the sankhara-khandha plays some of the roles

ascribed to the store-house consciousness by later Yogacara thinkers.

2.

^ Kalupahana: “The above

explanation of alaya-vijnana makes it very different from that found in

the Lankavatara. The latter assumes alaya to be the eight

consciousness, giving the impression that it represents a totally distinct

category. Vasubandhu does not refer to it as the eight, even though his later

disciples like Sthiramati and Hsuan Tsang constantly refer to it as such”.[9]

3.

^ Each being has his own one

and only, formless and no-place-to-abide store-house consciousness. Our

“being” is created by our own store-consciousness, according to the

karma seeds stored in it. In “coming and going” we definitely do not

own the “no-coming and no-going” store-house consciousness, rather we

are owned by it. Just as a human image shown in a monitor can never be

described as lasting for any instant, since “he” is just the

production of electron currents of data stored and flow from the hard disk of

the computer, so do seed-currents drain from the store-consciousness, never

last from one moment to the next.

4.

^ 心所法), self-delusion (我癡), self-view (我見),

egotism (我慢), and self-love (我愛)

5.

^ By then the polluted mental

functions of the first six consciousnesses would have been cleansed. The

seventh or the manas-consciousness determines whether or not the seeds and the

contentdrain from the alaya-vijnana breaks through, becoming a

“function” to be perceived by us in the mental or physical world.

6.

^ In contrast to an Arahat, a

Buddha is one with all his seeds stored in the eighth Seed consciousness.

Cleansed and substituted, bad for good, one for one, his

polluted-seeds-containing eighth consciousness (Alaya Consciousness) becomes an

all-seeds-purified eighth consciousness (Pure consciousness 無垢識 ), and he becomes a Buddha.

7.

^ The womb or matrix of the

Thus-come-one, the Buddha

8.

^ It is found in Chapter 7 of

the Platform

Sutra

of the Sixth Ancestor Zen Master Huineng

and other Zen masters, such as Hakuin Ekaku, in his work titled Keiso

Dokuqui[25],

and Xuyun, in his work titled Daily

Lectures at Two Ch’an Weeks, Week 1, Fourth Day.[26]

Korea

The Interpenetration (通達) and Essence-Function

(體用) of Wonhyo (元曉) is described in the Treatise on Awakening Mahāyāna Faith (AMF):

The author of the

AMF was deeply concerned with the question of the respective origins of

ignorance and enlightenment. If enlightenment is originally existent, how do we

become submerged in ignorance? If ignorance is originally existent, how is it

possible to overcome it? And finally, at the most basic level of mind, the alaya

consciousness (藏識), is there originally purity or taint? The AMF

dealt with these questions in a systematic and thorough fashion, working

through the Yogacāra concept of the alaya consciousness. The technical

term used in the AMF which functions as a metaphorical synonym for

interpenetration is “permeation” or “perfumation (薫),”

referring to the fact that defilement (煩惱)

“perfumates” suchness (眞如), and suchness

perfumates defilement, depending on the current condition of the mind.[27]