340 and 339 LESSON 09 and 08 08 2011

Madhupindika Sutta The Ball of Honey

Udayi Sutta About Udayin FREE ONLINE eNālandā Research and Practice

UNIVERSITY and BUDDHIST GOOD NEWS letter to VOTE for BSP ELEPHANT to attain

Ultimate Bliss-Through http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org- Free Buddhist Studies for Young Students- Lesson 4: Life Story of the Buddha –In

Search of Truth and Lesson 5: Life Story of the Buddha –The First Discourse

AN 5.159

PTS: A iii 184

Udayi Sutta: About

Udayin

translated from the Pali

by

Thanissaro Bhikkhu

I have heard that on one occasion the Blessed One was staying at

Kosambi, in Ghosita’s Park. Now at that time Ven. Udayin

was sitting surrounded by a large assembly of householders, teaching the

Dhamma. Ven. Ananda saw Ven. Udayin sitting surrounded by a

large assembly of householders, teaching the Dhamma, and on seeing him went to

the Blessed One. On arrival, he bowed down to the Blessed One and sat to one

side. As he was sitting there he said to the Blessed One: “Ven. Udayin,

lord, is sitting surrounded by a large assembly of householders, teaching the

Dhamma.”

“It’s not easy to teach the Dhamma to others, Ananda. The

Dhamma should be taught to others only when five qualities are established

within the person teaching. Which five?

“[1] The Dhamma should be taught with the thought, ‘I will

speak step-by-step.’

“[2] The Dhamma should be taught with the thought, ‘I will

speak explaining the sequence [of cause & effect].’

“[3] The Dhamma should be taught with the thought, ‘I will

speak out of compassion.’

“[4] The Dhamma should be taught with the thought, ‘I will

speak not for the purpose of material reward.’

“[5] The Dhamma should be taught with the thought, ‘I will

speak without hurting myself or others.’[1]

“It’s not easy to teach the Dhamma to others, Ananda. The

Dhamma should be taught to others only when these five qualities are

established within the person teaching.”

Lesson 4: Life Story of the Buddha –

In Search of Truth

1. Where did Siddhattha go

after he left the palace?

2. Discuss the story of the

wounded lamb and fire ceremony. What did

Siddhattha tell the king

Bimbisara and why?

3. Who were Siddhattha’s

meditation teachers, what did they teach

him, and why did he leave

them?

4. What is asceticism and why

did people practice it?

5. Describe Siddhattha’s life

as an ascetic. What happened to him at

the end?

6. What very important qualities

did Siddhattha show before he

became Buddha?

18

1. What did Siddhattha

discover while sitting under the Bodhi tree,

and how did he discover it?

2. What is the law of Kamma?

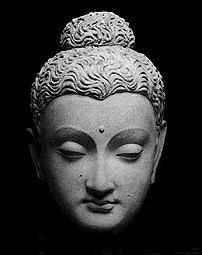

3. Why is the Buddha pictured

with a circle around his head?

1.

a) Have you ever saved an

animal from dying? If so, write a short

story or tell others about

it.

b) Do you know of some

people, now living or from the past, who

saved other people from

suffering and death? If so, describe what they

did and why they did it.

2.

a) Do you sometimes overeat,

eat unhealthy food, or skip meals? Do

you sometimes get very tired

from your schoolwork?

b) Do you think it is good to

go to extremes, and overdo things? If not,

why not?

19

3. Do you like natural

science at school? What are your favorite topics

and why?

4. What is meditation? Try a

short meditation on breathing (ask your

teacher, or use the Appendix

of this book for instructions).

?

1. Why did the prehistoric

people begin using fire, and how did they

make it?

2. Use your library or

Internet resources to find out about lives of

several famous scientists

(e.g. Galileo, Newton, Darwin and others).

What did all those scientists

have in common? How do we benefit

from their discoveries?

3. How can we benefit from

the Buddha’s discoveries?

Madhupindika Sutta: The

Ball of Honey

translated from the Pali

by

Thanissaro Bhikkhu

Translator’s

Introduction

This discourse plays a central role in the early Buddhist

analysis of conflict. As might be expected, the blame for conflict lies within,

in the unskillful habits of the mind, rather than without. The culprit in this

case is a habit called papañca. Unfortunately, none of the early texts

give a clear definition of what the word papañca means, so it’s hard to find a

precise English equivalent for the term. However, they do give a clear analysis

of how papañca arises, how it leads to conflict, and how it can be ended. In

the final analysis, these are the questions that matter — more than the precise

definition of terms — so we will deal with them first before proposing a few

possible translation equivalents for the word.

Three passages in the discourses — DN 21, MN 18, and Sn 4.11 — map the causal processes that give

rise to papañca and lead from papañca to conflict. Because the Buddhist

analysis of causality is generally non-linear, with plenty of room for feedback

loops, the maps vary in some of their details. In DN 21, the map reads like this:

the perceptions &

categories of papañca > thinking > desire > dear-&-not-dear >

envy & stinginess > rivalry & hostility

In Sn 4.11, the map is less linear and can be

diagrammed like this:

perception > the categories of papañca

perception > name & form > contact > appealing

& unappealing > desire > dear-&-not-dear >

stinginess/divisiveness/quarrels/disputes

In MN 18, the map is this:

contact > feeling

> perception > thinking > the perceptions & categories of papañca

In this last case, however, the bare outline misses some of the

important implications of the way this process is phrased. In the full passage,

the analysis starts out in an impersonal tone:

Dependent on eye &

forms, eye-consciousness arises [similarly with the rest of the six senses].

The meeting of the three is contact. With contact as a requisite condition,

there is feeling.

Starting with feeling, the notion of an “agent” — in

this case, the feeler — acting on “objects,” is introduced:

What one feels, one

perceives (labels in the mind). What one perceives, one thinks about. What one

thinks about, one “papañcizes.”

Through the process of papañca, the agent then becomes a victim

of his/her own patterns of thinking:

Based on what a person

papañcizes, the perceptions & categories of papañca assail him/her with

regard to past, present, & future forms cognizable via the eye [as with the

remaining senses].

What are these perceptions & categories that assail the

person who papañcizes? Sn 4.14 states that the root of the categories

of papañca is the perception, “I am the thinker.” From this self-reflexive

thought — in which one conceives a “self,” a thing corresponding to

the concept of “I” — a number of categories can be derived:

being/not-being, me/not-me, mine/not-mine, doer/done-to, signifier/signified.

Once one’s self becomes a thing under the rubric of these categories, it’s

impossible not to be assailed by the perceptions & categories derived from

these basic distinctions. When there’s the sense of identification with

something that experiences, then based on the feelings arising from sensory contact,

some feelings will seem appealing — worth getting for the self — and others

will seem unappealing — worth pushing away. From this there grows desire, which

comes into conflict with the desires of others who are also engaging in

papañca. This is how inner objectifications breed external contention.

How can this process be ended? Through a shift in perception,

caused by the way one attends to feelings, using the categories of appropriate

attention [see MN 2]. As the Buddha states in DN 21, rather than viewing a feeling as an

appealing or unappealing thing, one should look at it as part of a causal process:

when a particular feeling is pursued, do skillful or unskillful qualities

increase in the mind? If skillful qualities increase, the feeling may be

pursued. If unskillful qualities increase, it shouldn’t. When comparing

feelings that lead to skillful qualities, notice which are more refined: those

accompanied with thinking (directed thought) and evaluation, or those free of

thinking and evaluation, as in the higher stages of mental absorption, or

jhana. When seeing this, there is a tendency to opt for the more refined

feelings, and this cuts through the act of thinking that, according to MN 18,

provides the basis for papañca.

In following this program, the notion of agent and victim is

avoided, as is self-reflexive thinking in general. There is simply the analysis

of cause-effect processes. One is still making use of dualities —

distinguishing between unskillful and skillful (and affliction/lack of

affliction, the results of unskillful and skillful qualities) — but the

distinction is between processes, not things. Thus one’s analysis avoids the

type of thinking that, according to DN 21, depends on the perceptions and

categories of papañca, and in this way the vicious cycle by which thinking and

papañca keep feeding each other is cut.

Ultimately, by following this program to greater and greater

levels of refinement through the higher levels of mental absorption, one finds

less and less to relish and enjoy in the six senses and the mental processes

based on them. With this sense of disenchantment, the processes of feeling and

thought are stilled, and there is a breakthrough to the cessation of the six

sense spheres. When these spheres cease, is there anything else left? Ven. Sariputta,

in AN 4.174, warns us not to ask, for to ask if

there is, isn’t, both-is-and-isn’t, neither-is-nor-isn’t anything left in that

dimension is to papañcize what is free from papañca. However, this dimension is

not a total annihilation of experience. It’s a type of experience that DN 11 calls consciousness without feature,

luminous all around, where water, earth, fire, & wind have no footing,

where long/short, coarse/fine, fair/foul, name/form are all brought to an end.

This is the fruit of the path of arahantship — a path that makes use of

dualities but leads to a fruit beyond them.

It may come as cold comfort to realize that conflict can be

totally overcome only with the realization of arahantship, but it’s important

to note that by following the path recommended in DN 21 — learning to avoid references to any

notion of “self” and learning to view feelings not as things but as

parts of a causal process affecting the qualities in the mind — the basis for

papañca is gradually undercut, and there are fewer and fewer occasions for

conflict. In following this path, one reaps its increasing benefits all along

the way.

Translating

papañca: As one writer has noted, the word papañca

has had a wide variety of meanings in Indian thought, with only one constant:

in Buddhist philosophical discourse it carries negative connotations, usually

of falsification and distortion. The word itself is derived from a root that

means diffuseness, spreading, proliferating. The Pali Commentaries define

papañca as covering three types of thought: craving, conceit, and views. They

also note that it functions to slow the mind down in its escape from samsara.

Because its categories begin with the objectifying thought, “I am the

thinker,” I have chosen to render the word as “objectification,”

although some of the following alternatives might be acceptable as well:

self-reflexive thinking, reification, proliferation, complication, elaboration,

distortion. The word offers some interesting parallels to the postmodern notion

of logocentric thinking, but it’s important to note that the Buddha’s program

of deconstructing this process differs sharply from that of postmodern thought.

I have heard that on one occasion the Blessed One was living

among the Sakyans near Kapilavatthu in the Banyan Park. Then in the early morning,

having put on his robes and carrying his bowl & outer robe, he went into

Kapilavatthu for alms. Having gone for alms in Kapilavatthu, after the meal,

returning from his alms round, he went to the Great Wood for the day’s abiding.

Plunging into the Great Wood, he sat down at the root of a bilva sapling for

the day’s abiding.

Dandapani

(”Stick-in-hand”) the Sakyan, out roaming & rambling for

exercise, also went to the Great Wood. Plunging into the Great Wood, he went to

where the Blessed One was under the bilva sapling. On arrival, he exchanged

courteous greetings with him. After an exchange of friendly greetings &

courtesies, he stood to one side. As he was standing there, he said to the

Blessed One, “What is the contemplative’s doctrine? What does he proclaim?”

“The sort of doctrine, friend, where one does not keep

quarreling with anyone in the cosmos with its devas, Maras, & Brahmas, with

its contemplatives & priests, its royalty & commonfolk; the sort [of

doctrine] where perceptions no longer obsess the brahman who remains

dissociated from sensuality, free from perplexity, his uncertainty cut away,

devoid of craving for becoming & non-. Such is my doctrine, such is what I

proclaim.”

When this was said, Dandapani the Sakyan — shaking his head,

wagging his tongue, raising his eyebrows so that his forehead was wrinkled in

three furrows — left, leaning on his stick.

Then, when it was evening, the Blessed One rose from his

seclusion and went to the Banyan Park. On arrival, he sat down on a seat made

ready. As he was sitting there, he [told the monks what had happened]. When

this was said, a certain monk said to the Blessed One, “Lord, what sort of

doctrine is it where one does not keep quarreling with anyone in the cosmos

with its deities, Maras, & Brahmas, with its contemplatives & priests,

its royalty & commonfolk; where perceptions no longer obsess the brahman

who remains dissociated from sensuality, free from perplexity, his uncertainty

cut away, devoid of craving for becoming & non-?”

“If, monk, with regard to the cause whereby the perceptions

& categories of objectification assail a person, there is nothing there to

relish, welcome, or remain fastened to, then that is the end of the obsessions

of passion, the obsessions of resistance, the obsessions of views, the

obsessions of uncertainty, the obsessions of conceit, the obsessions of passion

for becoming, & the obsessions of ignorance. That is the end of taking up

rods & bladed weapons, of arguments, quarrels, disputes, accusations, divisive

tale-bearing, & false speech. That is where these evil, unskillful things

cease without remainder.” That is what the Blessed One said. Having said

it, the One Well-gone got up from his seat and went into his dwelling.

Then, not long after the Blessed One had left, this thought

occurred to the monks: “This brief statement the Blessed One made, after

which he went into his dwelling without analyzing the detailed meaning — i.e.,

‘If, with regard to the cause whereby the perceptions & categories of

objectification assail a person, there is nothing to relish… that is where

these evil, unskillful things cease without remainder’: now who might analyze

the unanalyzed detailed meaning of this brief statement?” Then the thought

occurred to them, “Ven. Maha Kaccana is

praised by the Teacher and esteemed by his knowledgeable companions in the holy

life. He is capable of analyzing the unanalyzed detailed meaning of this brief

statement. Suppose we were to go to him and, on arrival, question him about

this matter.”

So the monks went to Ven. Maha Kaccana and, on arrival exchanged

courteous greetings with him. After an exchange of friendly greetings &

courtesies, they sat to one side. As they were sitting there, they [told him

what had happened, and added,] “Analyze the meaning, Ven. Maha

Kaccana!”

[He replied:] “Friends, it’s

as if a man needing heartwood, looking for heartwood, wandering in search

of heartwood — passing over the root & trunk of a standing tree possessing

heartwood — were to imagine that heartwood should be sought among its branches

& leaves. So it is with you, who — having bypassed the Blessed One when you

were face to face with him, the Teacher — imagine that I should be asked about

this matter. For knowing, the Blessed One knows; seeing, he sees. He is the Eye, he is Knowledge, he is Dhamma, he is

Brahma. He is the speaker, the proclaimer, the elucidator of meaning, the giver

of the Deathless, the lord of the Dhamma, the Tathagata. That was the time when

you should have questioned him about this matter. However he answered, that was

how you should have remembered it.”

“Yes, friend Kaccana: knowing, the Blessed One knows;

seeing, he sees. He is the Eye, he is Knowledge, he is Dhamma, he is Brahma. He

is the speaker, the proclaimer, the elucidator of meaning, the giver of the

Deathless, the lord of the Dhamma, the Tathagata. That was the time when we

should have questioned him about this matter. However he answered, that was how

we should have remembered it. But you are praised by the Teacher and esteemed

by your knowledgeable companions in the holy life. You are capable of analyzing

the unanalyzed detailed meaning of this brief statement. Analyze the meaning,

Ven. Maha Kaccana!”

“In that case, my friends, listen & pay close

attention. I will speak.”

“As you say, friend,” the monks responded.

Ven. Maha Kaccana said this: “Concerning the brief

statement the Blessed One made, after which he went into his dwelling without

analyzing the detailed meaning — i.e., ‘If, with regard to the cause whereby

the perceptions & categories of objectification assail a person, there is

nothing there to relish, welcome, or remain fastened to, then that is the end

of the obsessions of passion, the obsessions of resistance, the obsessions of

views, the obsessions of uncertainty, the obsessions of conceit, the obsessions

of passion for becoming, & the obsessions of ignorance. That is the end of

taking up rods & bladed weapons, of arguments, quarrels, disputes,

accusations, divisive tale-bearing, & false speech. That is where these

evil, unskillful things cease without remainder’

“Dependent on eye & forms, eye-consciousness arises.

The meeting of the three is contact. With contact as a requisite condition,

there is feeling. What one feels, one perceives (labels in the mind). What one

perceives, one thinks about. What one thinks about, one objectifies. Based on

what a person objectifies, the perceptions & categories of objectification

assail him/her with regard to past, present, & future forms cognizable via

the eye.

“Dependent on ear & sounds, ear-consciousness arises…

“Dependent on nose & aromas, nose-consciousness

arises…

“Dependent on tongue & flavors, tongue-consciousness

arises…

“Dependent on body & tactile sensations,

body-consciousness arises…

“Dependent on intellect & ideas,

intellect-consciousness arises. The meeting of the three is contact. With

contact as a requisite condition, there is feeling. What one feels, one

perceives (labels in the mind). What one perceives, one thinks about. What one

thinks about, one objectifies. Based on what a person objectifies, the

perceptions & categories of objectification assail him/her with regard to

past, present, & future ideas cognizable via the intellect.

“Now, when there is the eye, when there are forms, when

there is eye-consciousness, it is possible that one will delineate a

delineation of contact.[1]

When there is a delineation of contact, it is possible that one will delineate

a delineation of feeling. When there is a delineation of feeling, it is

possible that one will delineate a delineation of perception. When there is a

delineation of perception, it is possible that one will delineate a delineation

of thinking. When there is a delineation of thinking, it is possible that one

will delineate a delineation of being assailed by the perceptions &

categories of objectification.

“When there is the ear…

“When there is the nose…

“When there is the tongue…

“When there is the body…

“When there is the intellect, when there are ideas, when

there is intellect-consciousness, it is possible that one will delineate a

delineation of contact. When there is a delineation of contact, it is possible

that one will delineate a delineation of feeling. When there is a delineation

of feeling, it is possible that one will delineate a delineation of perception.

When there is a delineation of perception, it is possible that one will

delineate a delineation of thinking. When there is a delineation of thinking, it

is possible that one will delineate a delineation of being assailed by the

perceptions & categories of objectification.

“Now, when there is no eye, when there are no forms, when

there is no eye-consciousness, it is impossible that one will delineate a delineation

of contact. When there is no delineation of contact, it is impossible that one

will delineate a delineation of feeling. When there is no delineation of

feeling, it is impossible that one will delineate a delineation of perception.

When there is no delineation of perception, it is impossible that one will

delineate a delineation of thinking. When there is no delineation of thinking,

it is impossible that one will delineate a delineation of being assailed by the

perceptions & categories of objectification.

“When there is no ear…

“When there is no nose…

“When there is no tongue…

“When there is no body…

“When there is no intellect, when there are no ideas, when

there is no intellect-consciousness, it is impossible that one will delineate a

delineation of contact. When there is no delineation of contact, it is

impossible that one will delineate a delineation of feeling. When there is no

delineation of feeling, it is impossible that one will delineate a delineation

of perception. When there is no delineation of perception, it is impossible

that one will delineate a delineation of thinking. When there is no delineation

of thinking, it is impossible that one will delineate a delineation of being

assailed by the perceptions & categories of objectification.

“So, concerning the brief statement the Blessed One made,

after which he entered his dwelling without analyzing the detailed meaning —

i.e., ‘If, with regard to the cause whereby the perceptions & categories of

objectification assail a person, there is nothing there to relish, welcome, or

remain fastened to, then that is the end of the obsessions of passion, the

obsessions of resistance, the obsessions of views, the obsessions of

uncertainty, the obsessions of conceit, the obsessions of passion for becoming,

& the obsessions of ignorance. That is the end of taking up rods &

bladed weapons, of arguments, quarrels, disputes, accusations, divisive

tale-bearing, & false speech. That is where these evil, unskillful things

cease without remainder’ — this is how I understand the detailed meaning. Now,

if you wish, having gone to the Blessed One, question him about this matter.

However he answers is how you should remember it.”

Then the monks, delighting & approving of Ven. Maha

Kaccana’s words, rose from their seats and went to the Blessed One. On arrival,

having bowed down to him, they sat to one side. As they were sitting there,

they [told him what had happened after he had gone into his dwelling, and ended

by saying,] “Then Ven. Maha Kaccana analyzed the meaning using these

words, statements, & phrases.”

“Maha Kaccana is wise, monks. He is a person of great

discernment. If you had asked me about this matter, I too would have answered

in the same way he did. That is the meaning of this statement. That is how you

should remember it.”

When this was said, Ven. Ananda

said to the Blessed One, “Lord, it’s as if a

man — overcome with hunger, weakness, & thirst — were to come across a ball

of honey. Wherever he were to taste it, he would experience a sweet, delectable

flavor. In the same way, wherever a monk of capable awareness might investigate

the meaning of this Dhamma discourse with his discernment, he would experience

gratification, he would experience confidence. What is the name of this Dhamma

discourse?”

“Then, Ananda, you can remember this Dhamma discourse as

the ‘Ball of Honey Discourse.’”

That is what the Blessed One said. Gratified, Ven. Ananda

delighted in the Blessed One’s words.

Lesson 5: Life Story of the Buddha –

The First Discourse

1. What did the Buddha do

after he attained the Supreme

Enlightenment?

2. Why did he decide to teach

others? Who did he decide to teach first

and why?

3. Describe what happened

when he met his old ascetic friends.

4. What was the Buddha’s

first discourse called and why?

The Buddha taught people the 4 Noble Truths:

The Noble Truth of Suffering

The Buddha taught that birth,

sickness, old age, death, not getting

what we desire or getting

what we do not desire is suffering.

The Noble Truth of the Origin of Suffering

The Buddha taught that the

origin (cause) of suffering is craving

(selfish desire). He also

said that this selfish desire is a result of

ignorance.

The Noble Truth of the End of Suffering

The Buddha taught that the

end of suffering is the end of the craving

(selfishness). This also

means the end of greed, hate and delusion.

This end is called Nibbana.

It is the highest happiness and peace.

The Noble Truth of the Way Leading to the

End of Suffering

The Buddha taught that the

way leading to the end of suffering is a

middle way between the two

extremes of self-indulgence and selfinjury.

It is the Noble Eightfold

Path, and it consists of right

understanding, right thought,

right speech, right action, right

livelihood, right effort,

right mindfulness and right concentration.

The Buddha was like a scientist

or a medical doctor, who not only

recognised the suffering in

the world, but discovered the deep causes

of it, freed or cured

himself, and taught others the way to free

themselves. His teaching is

like a medicine, that when used properly

can bring peace and freedom.

The Buddha’s teaching is

symbolised by the Wheel of the Dhamma:

1.

Do you think it is important

to think about the 4 Noble Truths? Why?

2.

What are some things in your

life that made you suffer or unhappy?

Name and discuss some.

3.

a) List some words that have

similar meaning as ‘craving’.

b) Why do some people kill or

hurt other people or animals?

c) Discuss why some people

create violent stories, games and movies.

4.

a) Name a few things that

make you feel happy.

b) Draw a picture of a happy

person or of a happy place.

c) What is peace? What does

peace mean to you?

d) Write a poem about peace

or draw a picture of a peaceful place.

5.

a) Why is the way out of

suffering called the Noble Eightfold Path?

b) What does right and wrong mean

to you? Give examples.

c) How do we get started on

the Noble Eightfold Path?

d) A gardener cultivates

(grows) flowers, fruits and vegetables. How

does (s)he do it?

e) How do we cultivate

understanding? Give some ideas.

6. What do you have to do, if

you want to:

play a musical instrument?

paint pictures?

play a sport well?

use a computer?

build a house?

understand how plants and

animals live?

heal people?

live in a peaceful world?

7. Draw the Wheel of the

Dhamma. Why does it have 8 spokes?

8. Read the Buddha’s First

Discourse, in the Buddhist scriptures or in

The Book of Protection (see

References). Discuss it first at home with

your parents or friends, and

then in the class with other students.

QUIZ on the

best way

What is the best way to keep

your room and house tidy?

What is the best way to keep

healthy until you are very old?

What

is the best way to improve in your schoolwork and

exams?

What is the best way to keep

your neighborhood and country

free from litter?

What is the best way to keep

the oceans free from pollution?

What is the best way to stop

and prevent the global warming?

338 LESSON Udayi Sutta About Udayin

08 08 2011 FREE

ONLINE eNālandā Research and Practice UNIVERSITY and BUDDHIST GOOD NEWS letter

to VOTE for BSP ELEPHANT to attain Ultimate Bliss-Through http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org- Free Buddhist Studies for

Young Students- Lesson 4: Life Story

of the Buddha –In Search of Truth