Sotthi Hotu, Namo Buddhaya

Bagaimana kabar Anda hari ini?

Semoga senantiasa selalu berbahagia

Sadhu…

Tulisan kali ini berisikan tentang sebuah kisah nyata dari seorang yang berhasil mengubah hidupnya ke arah yang lebih baik. 1,334 more words

Tipiṭaka Studies for University Students

Day Programme : 2 hrs.

Organised annually since 2003 for 1st Year Students of Sport Science Faculty, Chulalongkorn University

at the International Tipiṭaka Hall, Chulalongkorn University

B.E. 2546 (2003)

Image printed from the Dhamma Society Electronic Archives

500-hour/6500-gigabyte documentary of the World Tipiṭaka Project

Recorded between 1999-2007

for more image information of the World Tipiṭaka Project

https://www.flickr.com/photos/

World Tipiṭaka Foundation by Dhamma Society

Pāḷi Tipiṭaka in Roman-script to the International Phonetic Alphabet for Pāḷi Transcription

The International Phonetic Alphabet for Pāḷi (IPA Pāḷi) 2008 as

proposed by Emeritus Professor Vichin Phanupong, Ph.D., to be used in

the printing of the World Tipiṭaka Edition 2009 and the newly revised

2010 Chulachomklao Tipiṭaka of Siam Anthology.

“…To

explain the special phonological features of the Pāḷi used in the sacred

Buddhist texts, the Dhamma Society, invited Professor Emeritus Dr.

Vichin Panupong to prepare a handbook on the pronunciation of Pāḷi words

used in the Tipiṭaka and their transcription in Roman script entitled

“Pāḷi and the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA).”

Her

work is a milestone in the academic study of the Tipiṭaka recitation,

integrating current knowledge from various fields and setting an example

for internationalizing the study of the Theravāda Buddhist scriptures,

i.e., Tipiṭaka Studies, a new academic discipline to study the Pāḷi

Tipiṭaka for laity, envisioned by Her Royal Highness Princess Galyani

Vadhana, who in 2004, expressed her gracious support for disseminating

knowledge of the Tipiṭaka to people all around the world.” (from the

preface of King of Siam Digital Preservation Edition 2009)

Prof. Emeritus Vichin is the founder of Linguistics Department at

Chulalongkorn University, the first linguistics studies in the country,

the first President of the International Tipiṭaka Hall at Chulalongkorn

University between 2002-2005, and is now an Associate Fellow of the Arts

Academy, the Royal Institute in Bangkok.

The article “Pāḷi

and the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA)” is, therefore, a research

in response to the wishes of the late Princess and is humbly dedicated

to Her Royal Highness in respectful gratitude for her patronage of this

project. The article appears at the end of each volume of the new

40-volume publication, “Chulachomklao of Siam Pāḷi Tipiṭaka 1893 : A

Digital Preservation Edition 2009”.

Digital Archives from Dhamma Society’s World Tipiṭaka Projects in Roman Script, 1999-2010. www.tipitakahall.net

การศึกษาการออกเสียงตามสัททอั

ช่วยให้สามารถอ่านพระไตรปิ

ซึ่งจะเป็นประโยชน์ในการจั

อันเป็นกิจกรรมที่เป็นทั้งกุ

สัททอักษรสากลปาฬิ (International Phonetic Alphabet Pāḷi, IPA Pāḷi)

จัดทำโดยศาสตราจารย์กิตติคุณ ดร. วิจินตน์ ภาณุพงศ์

ผู้เชี่ยวชาญด้านภาษาศาสตร์

เอกสารนี้เป็นส่วนหนึ่

การอ่านสังวัธยายพระไตรปิฎกสากล นำโดย ดร. วิจินตน์ ภาณุพงษ์ ณ รร.จปร. 25

มิถุนายน 2552

ในเดือน พศจิกายน พ.ศ. 2552 อาจารย์วิจินตน์

ได้รับเชิญเป็นผู้ฝึกการอ่านสั

แก่อนุศาสนาจารย์

เนื่องในโอกานที่

ตามรอยพระไตรปิฎก จปร. อัษรสยาม ถวายแด่สมเด็จพระสังฆราช ณ

วัดพระศรีรัตนศาดาราม ซึ่งในพิธีดังกล่าวได้มีการอ่

เป็นภาษาปาฬิ และภาคแปลเป็็นภาษาไทย

เป็นพระราชกุศลแด่สถาบั

Please see the updated version at :

International Phonetic Alphabet for Pāḷi

https://buddhavasse.blogspot.

Buddhavasse 2500

หนังสือสวดมนต์ จปร.ฉบับสากล อักษรสยาม 2554

17 October 2011 5:18 PM

Open publication - Free publishing - More alphabet

ผลงานที่ได้จากการจาริกไปพม่า..

เล่ม โดยกองทุนสนทนาธัมม์นำสุขฯ ชื่อ “พระไตรปิฎกเบ่มประมวลเนื้อหา

(Anthology)” เทียบระหว่าง ฉบับ ปาฬิภาสา-อักษรสยาม พ.ศ. 2436 กับ

ปาฬิภาสา-อักษรพม่า พ.ศ. 2500 และ ปาฬิภาสา-อักษรโรมัน พ.ศ. 2548.

The World Tipiṭaka Edition in various scripts will be printed by Dhamma

Society, for the first time — in parallel corpus for all to study and

understand…

As you see, the parallel corpus brings a great deal

more profound perspective of these sacred scripts — an ingenious

attempt to preserve the original sounds of Dhamma in various scripts to

ensure the correctness.

ข้อมูลนี้จะทำให้ประชาชนทั่

และการจัดพิมพ์พระไตรปิฎก ฉบับสังคายนาสากล ฉบับอักษรต่างๆ

รวมฉบับสากล-อักษรโรมันชุดที่

ภาพบรรยากาศการถวายพระไตรปิฎก จปร. อักษรสยาม ณ วัดป่าบ้านตาด

3 April 2011 5:57 PM

ภาพ เตรียมการอัญเชิญ พระไตรปิฎก จปร. ปาฬิภาสา-อักษรสยาม พ.ศ. 2436

ฉบับอนุรักษ์ดิจิทัล พ.ศ. 2554 ในวันมาฆบูชา 18 กุมภาพันธ์ พ.ศ. 2554 ณ

วัดป่าบ้านตาด อุดรธานี

…เนื่องด้วยในปลายปี พ.ศ. 2553

คณะสงฆ์ผู้ที่คณะกรรมการ “มูลนิธิเสียงธรรมเพื่

ได้ปรารถถึงความสำคัญของอั

โดยใช้พิมพ์กำกับเสียงสวดมนต์ผ่

และทางวิทยุของสถานีวิทยุเสี

โครงการพระไตรปิฎกสากลและกองทุ

ผู้ดำเนินงานเผยแผ่ข้อมู

จึงได้มอบข้อมูลพระไตรปิฎกอิเล็

ต่อ มาในปี พ.ศ. 2554

เมื่อได้มีการประชุมร่วมระหว่

และกองทุนสนทนาธัมม์นำสุขฯ ในพระสังฆราชูปถัมภ์ฯ มากขึ้น

มูลนิธิเสียงธรรมเพื่อประชาชนจึ

ไตรปิฎก จปร. อักษรสยาม พ.ศ. 2436 ซึ่งเป็น “ต้นฉบับ”

ที่สำคัญในการจัดทำฐานข้อมูล “ปาฬิภาสา-อักษรโรมัน” พ.ศ. 2548

ดัง

นั้นเมื่อพระอาจารย์พระมหาบั

โครงการพระไตรปิฎกสากล และกองทุนสนทนาธัมม์นำสุขฯ ในพระสังฆราชูปถัมภ์ฯ

จึงได้มีจิตศรัทธาอย่างแรงกล้

ฉบับอนุรักษ์ดิจิทัล พ.ศ. 2554 ซึ่งได้จัดพิมพ์ขึ้นใหม่ เป็นชุดพิเศษ ชุด

40 เล่ม ชุดเดียวในประเทศไทยในปีนี้ และเมื่อได้รับความเห็

ก็ได้ทำการอัญเชิญพระไตรปิฎก จปร. อักษรสยาม ไปประดิษฐาน ณ วัดป่าบ้านตาด

ทั้งนี้เพื่อทางคณะสงฆ์

จะได้พิจารณานำข้อมูล และเนื้อหาไปเผยแผ่ต่อไป

ตามเจตนารมย์ของพระอาจารย์

ผู้ซึ่งปฏิบัติตามธั

และเนื่องด้วย

พระไตรปิฎก จปร. อักษรสยาม มีระบบอักขรวิธีการเขียนปาฬิ

คือมีเครื่องหมายสัญลักษณ์ “ไม้ยามักการ” กำกับเสียงควบกล้ำที่ชัดเจน

พระไตรปิฎก จปร. อักษรสยามชุดนี้

จึงเป็นเอกสารที่สำคัญยิ่งที่

ซึ่งเป็นเสียง “ปาฬิภาสา”

ที่ทางวัดป่าอรัญญวาสีได้สื

และการออกเสียงที่ได้

นอกจากนั้นที่สำคัญ

ยิ่งยวดอีกประการก็คือ พระไตรปิฎก จปร. อักษรสยาม เมื่อ พ.ศ. 2436

เป็นการจัดพิมพ์พระไตรปิฎกปาฬิ

โดยพระบาทสมเด็จพระจุลจอมเกล้

ทรงโปรดให้เปลี่ยนวิธีการอนุรั

มาเป็นกระดาษที่ทันสมัย และยังได้ตีพิมพ์เป็น “อักษรสยาม” แทน “อักษรขอม”

ซึ่งอักษรสยามก็คือ

อักษรที่ใช้เขียนภาษาไทยที่

การ

ดำเนินงานและจัดพิมพ์พระไตรปิฎก จปร.

เป็นช่วงที่สยามต้องเผชญกับวิ

ประเทศมหาอำนาจตะวันตก โดยเฉพาะฝรั่งเศส ซึ่งในปีรัตนโกสินทรศก ร.ศ. 112

หรือ พ.ศ. 2436 ฝรั่งเศสได้ส่งเรือรบมาปิดอ่

หมายจะยึดครองไทยเป็นเมืองขึ้น แต่แม้กระนั้น ไทยก็มีขันติธัมม์

และสามารถอดกลั้นต่ออกุสลทั้

และด้วยความชาญฉลาดของผู้นำกรุ

และพระไตรปิฎก ฉบับ จปร. ก็จัดพิมพ์สำเร็จในปีนี้ด้วย

อันเป็นมงคลของประเทศ ที่แม้มีปัญหารอบด้าน แต่สยามก็เป็นพระธัมมนคร

สามารถจัดสร้างพระไตรปิฎกเป็นชุ

เป็นพระธัมมทานไปทั่วสยาม และยังได้พระราชทานไปเป็นพระธั

แก่สถาบันสำคัญมในนานาประเทศทั่

ด้วยเหตุสำคัญทางประวัติศาสตร์

จึงเป็นสัญลักษณ์ –ภาพรวม– ของสถาบันสำคัญสูงสุดของไทย คือ

สถาบันพระพุทธศาสนา สถาบันชาติเอกราช และสถาบันพระมหากษัตริย์พุ

ซึ่งล้วนเป็นสิ่งที่พระอาจารย์

ได้เมตตาปลูกฝังให้ชาวไทยตระหนั

ไพบูลย์ของลูกหลานไทยในภายหน้า จนเกิดมีโครงการผ้าป่าช่วยชาติ

ที่ชาวไทยทั้งหลายจะไม่มีวันลื

ขอหวังว่า

การจัดพิมพ์พระไตรปิฎก จปร. อักษรสยาม ฉบับอนุรักษ์ดิจิทัล 2554

และการที่ได้อัญเชิญมาน้

เนื่องในงานบำเพ็ญกุ

จะเป็นการบำเพ็ญบุญกิริ

ผู้อนุรักษ์พระไตรปิฎก และปฏิบัติตามพระไตรปิฎก

ตั้งแต่อดีตจนถึงปัจจุบัน…

ข้อมูลเพื่มเติม

http://www.facebook.com/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?

How I learned Pali (Theravada Buddhism) and my Positive Experiences in the Field

à-bas-le-ciel

Published on Jun 26, 2015

I taught myself Pali and lived for years in Theravada Countries in

Asia. Learning the language is hard work, and this video may motivate

you by discussing some of the positive outcomes of learning the

language; I had a lot of positive experiences in both monastic and

academic settings (and archives, museums, etc.)

and most of my writing (on the internet) about learning Pali instead

provides pretty “dry” advice (and, sometimes, some grave warnings). So,

this is a relatively upbeat video, for people interested in the human

reality of what it means to be a Pali scholar in the 21st century –an

era when every Pali scholar is an autodidact.

As is mentioned in the video, you can find the resources I created to

help people learn Pali in various places, including Google Books (for

free, of course):

https://www.google.ca/search?

For some much more depressing, practical advice (on learning the Pali

language), you can take a look at some of my written work, e.g.,

http://a-bas-le-ciel.blogspot.

A useful essay for any beginner (both providing useful information, and

warnings about misinformation in the field) can be found in both

English and Chinese translation through the following links: http://a-bas-le-ciel.blogspot.

You might also be interested in my more recent video (over 20 minutes

long), on the question of, “What is the future of Buddhism?”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?

Category

Education

http://tipitaka.sutta.org/

Welcome to Online Pāḷi Tipiṭaka Website!

This website (website source code, data) allows instant lookup of words

when mouse cursor hovers over words, and contrast (parallel) reading of

Pāḷi texts and translations (if available). The dictionaries include

Pāḷi-English, Pāḷi-Japanese, Pāḷi-Chinese, Pāli-Vietnamese,

Pāli-Burmese. The data of Pāḷi Tipiṭaka in this website comes from Pāḷi

Tipiṭaka. Before using this website, please read Howto on Pāḷi Tipiṭaka

first. If you only need to look up Pāḷi words, please visit Pāḷi

Dictionary (website source code, data). The data of dictionaries comes

from Pali Canon E-Dictionary Version 1.94 (PCED). This website is still

under development, if any questions, problems, or suggestions, please

contact me.

Firefox and Chrome are preferred browsers for this website. IE8 or older are not supported.

Notice:

The data of Pāḷi Tipiṭaka in this website comes from V.R.I. (Vipassana

Research Institute, India) & the VRI editions are based on the

Burmese texts (Chaṭṭhasaṅgāyana edition).

During compiling Pāḷi

text, we have perceived some misplacements and these points have been

confirmed by VRI. According to VRI, the misplacements had been occurring

from the Chaṭṭhasaṅgāyana edition.

The misplacements are being on these paths:

1. Tipiṭaka (Mūla) (Pāḷi Canon) >> Suttapiṭaka (The Basket of

Discourses) >> Aṅguttaranikāya (Further-factored Discourses)

>> Ekakanipātapāḷi (Book of the Ones) >> 9. Pamādādivaggo,

the paragraph #81 should belong to the previous chapter (8.

Kalyāṇamittādivaggo) instead of current state.

2. Tipiṭaka (Mūla)

(Pāḷi Canon) >> Suttapiṭaka (The Basket of Discourses) >>

Aṅguttaranikāya (Further-factored Discourses) >> Ekakanipātapāḷi

(Book of the Ones) >> 10. Dutiyapamādādivaggo, the paragraphs 130

to 139 should belong to the next chapter (11. Adhammavaggo) instead of

current state.

Analytic

Tipiṭaka Studies for University Students

Insight Net - GRATIS online Tipiṭaka Onderzoek en praktijk Universiteit

en aanverwant NIEUWS via http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org in 105 KLASSIEKE

TALEN

https://www.youtube.com/watch…

24 Classical Esperanto

24 Klasika Esperanto

Analytic Insight Net - Senpaga Enreta Tipiṭaka Esplorado kaj Praktiko de Universitato kaj rilataj NOVAĴOJ per http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org en 105 CLASSICAL LANGUAGES

https://en.wordpress.com/tag/agama-buddha/

25 Classical Estonian25 klassikaline eesti keel

Analüütika Insight Net - TASUTA Online Tipiťaka Uurimis- ja praktikaülikool ja sellega seotud UUDISED läbi http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org 105 KLASSI KEELADES

Sotthi Hotu, Namo Buddhaya

Bagaimana kabar Anda hari ini?

Semoga senantiasa selalu berbahagia

Sadhu…

Tulisan kali ini berisikan tentang sebuah kisah nyata dari seorang yang berhasil mengubah hidupnya ke arah yang lebih baik. 1,334 more words

Sotthi Hotu, Namo Buddhaya

Bagaimana kabar Anda hari ini?

Semoga kita semua senantiasa berbahagia

Sadhu…

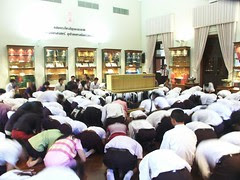

Tulisan kali ini berisikan materi lanjutan mengenai Kitab Suci Agama Buddha, yaitu… 705 more words

Sotthi Hotu, Namo Buddhaya

Bagaimana kabar Anda hari ini?

Semoga kebahagiaan selalu menyertai Anda sekalian

Sadhu..

Tulisan kali ini akan melanjutkan tulisan terdahulu mengenai Kitab Suci Agama Buddha, yaitu 1,368 more words

Sotthi Hotu, Namo Buddhaya

Semoga Kita senantiasa selalu berbahagia.

Sadhu..Sadhu..Sadhu..

Tulisan ini merupakan lanjutan dari post sebelumnya. Awalnya, penulis

berniat menggabung keduanya. Akan tetapi, Penulis mengurungkan kehendak

tersebut karena perbedaan topik. 1,679 more words

Sotthi Hotu, Namo Buddhaya

Semoga Kita Senantiasa Berbahagia

Hari Minggu, 29 Oktober 2017 merupakan hari yang begitu menyenangkan.

Kalian ingin tahu alasannya?

Silahkan baca tulisan ini dengan penuh perhatian ![]() … 2,030 more words

… 2,030 more words

Sotthi Hotu, Namo Buddhaya

Semoga Kita Senantiasa Berbahagia

Sadhu…

Tulisan kali ini akan berisikan sebuah pedoman hidup untuk semua

makhluk. Mengapa? Karena yang tertulis disini adalah Dhamma (Kebenaran).

803 more words

Sotthi Hotu, Namo Buddhaya

Semoga Kita Senantiasa Selalu Berbahagia

Sadhu…

Berbeda dari biasanya, Penulis tidak membahas mengenai Chord Lagu

Buddhis, Teori Dhamma atau pun pengalaman mengenai perjalanan kehidupan.

1,300 more words

Sotthi Hotu, Namo Buddhaya

Semoga kita sekalian senantiasa sehat dan berbahagia

Sadhu…

Dewasa ini, banyak orang yang belum mengetahui bahwa mereka telah membawa-bawa beban yang begitu banyak dalam hidupnya. 1,938 more words

Sotthi Hotu, Namo Buddhaya

Semoga Kita Senantiasa Berbahagia

Dewasa ini, sering kali ditemukan banyak orang yang berusaha keras

mengejar kebahagiaan dalam hidupnya. Pernahkah kita meresapi kalimat

perenungan bahwa… 1,175 more words

2506 Fri 19 Jan 2018 LESSON Tipiṭaka Studies for University Students

27 Classical Finnish-klassista suomalaista,

Sotthi Hotu, Namo Buddhaya

Semoga Anda senantiasa berbahagia ![]()

Dewasa ini, perkembangan dunia IPTEK sangat cepat. Akan tetapi, tidak

diimbangi dengan moral manusia. Sehingga sering kali ditemui

kejadian-kejadian yang diluar nalar manusia. 1,103 more words

Sotthi Hotu, Namo Buddhaya

Tulisan ini akan membahas mengenai sila dalam Agama Buddha, khususnya

Pancasila Buddhis yang wajib dijalankan oleh upasaka dan upasika.

Sebelum membahas lebih jauh mengenai sila, marilah kita sama-sama

membaca penggalan Dhammapada, yaitu sebagai berikut. 1,023 more words

Sotthi Hotu, Namo Buddhaya

Semoga Anda senantiasa berbahagia ![]()

Sadhu..

Sesuai dengan yang telah dijanjikan pada post sebelumnya, penulis

akan membahas singkat mengenai apa dan bagaimana berdoa menurut Agama

Buddha? 1,048 more words

Sotthi Hotu, Namo Buddhaya

Bagaimana kabar Anda hari ini?

Semoga Anda senantiasa berbahagia. Sadhu :)

Dewasa ini, banyak ditemui beberapa pandangan yang keliru mengenai Agama Buddha. 1,157 more words

Sotthi Hotu, Namo Buddhaya

Peluang menulis kali ini digunakan untuk menceritakan Perayaan Asadha

Puja 2561 BE/2017 di Vihara Dhamma Sabha. Perayaan Asadha Puja Vihara

Dhamma Sabha dilaksanakan di Hari Minggu, 30 Juli 2017 mulai pukul 08.00

WIB. 781 more words

Sotthi Hotu,

Bagaimana kabarnya hari ini?

Semoga hari Anda sekalian senantiasa berbahagia. ![]()

Topik yang akan dibahas kali ini adalah hidup bersama pasangan yang ideal menurut pandangan Agama Buddha. 1,440 more words

Sotthi Hottu, Namo Buddhaya

Saya akan membahas mengenai Kitab Suci Agama Buddha, yaitu

Tipiṭaka (literatur berbahasa Pāli).

Selamat membaca ![]()

Tipiṭaka berarti 3 keranjang, yang bermakna Tiga Wadah yang berisi ajaran Buddha. 486 more words

Sotthi Hotu, Namo Buddhaya ![]()

Tulisan kali ini akan membahas mengenai kelembagaan umat Buddha, khususnya lembaga keagamaan umat Buddha mazhab Therāvada.

Apa itu kelembagaan? Kelembagaan mempunyai kata dasar lembaga, berarti

organisasi yang bertujuan melakukan suatu penyelidikan keilmuan. 590 more words

Sotthi Hotu, Namo Buddhaya

Tulisan saya kali ini membahas tentang “Cara menjadi bahagia”.

Banyak manusia mendambakan kebahagiaan. Apakah kita salah satu diantara

mereka? Tahukah kita bagaimana untuk mendapatkan kebahagiaan sejati? 604 more words

Sotthi Hotu, Namo Buddhaya

Saya akan membahas mengenai umat buddha sejati. Apa yang dimaksud

dengan umat buddha yang sejati? Umat Buddha yang sejati adalah umat

Budhha yang menjalankan ajaran Buddha dalam kehidupan sehari-hari. 300 more words

Sotthi Hotu, Namo Buddhaya

Tulisan saya kali ini diambil dari buku berjudul “Don’t worry be hopey” karya Ajahn Brahm.

Selamat membaca ![]()

Kebanyakan penindas memiliki rasa percaya diri yang rendah. 317 more words

Sotthi Hotu, Namo Buddhaya

Banyak orang yang takut akan kematian. Mereka ingin hidup selamanya.

Bahkan, mereka berdalih jika mereka akan meninggal ketika urusan mereka

telah selesai di dunia. 366 more words

Sotthi Hotu, Namo Buddhaya.

Tulisan saya kali ini akan membahas mengenai salah satu hari raya

bagi umat buddha, yaitu Hari Raya Magha Puja. Secara umum, ada 4 Hari

Raya dalam Agama Buddha, yaitu Waisak, Asadha, Kathina, dan Magha Puja. 530 more words

Sotthi Hotu, Namo Buddhaya…

Saya akan menulis ulang mengenai topik yang sama seperti di post pertama, yaitu Tilakhana atau biasa dikenal dengan Tiga Corak Umum. 547 more words

SUTRA AVALOKITESVARA RAJA GAO.

佛說高王觀世音經

Fo shuō gāo wáng guānshìyīn jīng

Taisho Tripitaka 2898

Diterjemahkan dari bahasa Mandarin ke bahasa Indonesia oleh Ivan Taniputera. 2,635 more words

SUTRA AVALOKITESVARA RAJA GAO.

佛說高王觀世音經

Fo shuō gāo wáng guānshìyīn jīng

Taisho Tripitaka 2898

Diterjemahkan dari bahasa Mandarin ke bahasa Indonesia oleh Ivan Taniputera. 2,635 more words

http://quantumleapalchemy.com/…/bigstock-Molecular-Thoughts…

26 Classical Filipino

Analytic Insight Net - LIBRE Online Tipiṭaka Research and Practice University at mga kaugnay na BALITA sa pamamagitan ng http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org sa 105 Classical LANGUAGES

https://www.revolvy.com/main/index.php…

27 Classical Finnish

27 klassista suomalaista

Analytic Insight Net - ILMAINEN Online Tipiṭaka Research and Practice University ja siihen liittyvät uutiset osoitteessa http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org 105 CLASSICAL LANGUAGES

|

The Western canon is the body of books, music, and art that scholars generally accept as the most important and influential in shaping Western culture. It includes works of fiction, non-fiction, poetry, drama, music, art, sculpture, and architecture generally perceived as being of major artistic merit and representing the high culture of Europe and North America. University of California philosopher John Searle suggests that the Western canon can be roughly defined as “a certain Western intellectual tradition that goes from, say, Socrates to Wittgenstein in philosophy, and from Homer to James Joyce in literature”.[1] The Bible, a product of Middle Eastern culture, has been a major force in shaping Western culture, and “has inspired some of the great monuments of human thought, literature, and art”.[2]

The canon of books, including Western literature and Western philosophy, has been fairly stable, although it has expanded to include more women and racial minorities, while the canons of music and the visual arts have greatly expanded to cover the Middle Ages

and subsequent centuries once largely overlooked. Also during the

twentieth century there has been a growing interest in the cultures of

Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and South America. In particular the

former colonies of European countries began in the twentieth century to

produce major works, both in literature and in the other arts. This is

especially reflected in the Nobel prizes awarded in literature. But some

examples of newer media such as cinema have attained a precarious position in the canon.

There

has been an ongoing debate over the nature and status of the canon,

especially in America, since at least the 1960s, much of which is rooted

in critical theory, feminism, critical race theory, and Marxism.[3] In particular, postmodern studies have argued that the body of scholarship is biased because the traditional main focus of academic studies of Western culture and history has only been on works produced by Western men.

A classic is a book, or any other work of art, accepted as being exemplary or noteworthy, for example through an imprimatur such as being listed in a list of great books,

or through a reader’s personal opinion. Although the term is often

associated with the Western canon, it can be applied to works of

literature, music and art, etc. from all traditions, such as the Chinese classics or the Vedas. A related word is masterpiece

or chef d’œuvre, which in modern use refers to a creation that has been

given much critical praise, especially one that is considered the

greatest work of a person’s career or to a work of outstanding

creativity, skill, or workmanship. Historically, the word refers to a

work of a very high standard produced in order to obtain membership of a

Guild or Academy.

The first writer to use the term “classic” was Aulus Gellius, a 2nd-century Roman writer who, in the miscellany

Noctes Atticae (19, 8, 15), refers to a writer as a classicus scriptor,

non proletarius (”A distinguished, not a commonplace writer”). Such

classification began with the Greeks’ ranking their cultural works, with

the word canon (”carpenter’s rule”). Moreover, early Christian Church Fathers used canon to rank the authoritative texts of the New Testament, preserving them, given the expense of vellum and papyrus

and mechanical book reproduction, thus, being comprehended in a canon

ensured a book’s preservation as the best way to retain information

about a civilization. Contemporarily, the Western canon defines the best

of Western culture. In the ancient world, at the Alexandrian Library, scholars coined the Greek term Hoi enkrithentes (”the admitted”, “the included”) to identify the writers in the canon.

With regard to books, what makes a book “classic” is a concern that has occurred to various authors ranging from Italo Calvino to Mark Twain

and the related questions of “Why Read the Classics?” and “What Is a

Classic?” have been essayed by authors from different genres and eras,

including Calvino, T. S. Eliot, Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve, Michael Dirda, and Ezra Pound.

The

terms “classic book” and Western canon are closely related concepts,

but they are not necessarily synonymous. A “canon” refers to a list of

books considered to be “essential” and is presented in a variety of

ways. It can be published as a collection (such as Great Books of the Western World, Modern Library, Everyman’s Library, or Penguin Classics), presented as a list with an academic’s imprimatur (such as Harold Bloom’s[4] ) or be the official reading list of an institution of higher learning.

Some of the writers who are generally considered the most important in Western literature are Homer, Aeschylus, Euripides, Virgil, Horace, Geoffrey Chaucer, Dante Alighieri, William Shakespeare, François Rabelais, Jean Racine, Molière, Camões, Miguel de Cervantes, Michel de Montaigne, John Milton, Samuel Johnson, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, William Wordsworth, Jane Austen, Stendhal, Walt Whitman, Gustave Flaubert, Emily Dickinson, Honoré de Balzac, Charles Dickens, Herman Melville, George Eliot, Leo Tolstoy, Henrik Ibsen, Sigmund Freud, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Eça de Queirós, Marcel Proust, Thomas Mann, Robert Musil, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, Franz Kafka, William Faulkner, Jorge Luis Borges, Pablo Neruda, Fernando Pessoa, Albert Camus and Samuel Beckett.[5] [6]

Harold Bloom has divided the body of Western Literature into four ages[7] :

A university or college Great Books Program is a program inspired by the Great Books movement begun in the United States in the 1920s by Prof. John Erskine of Columbia University,[9] which proposed to improve the higher education system by returning it to the western liberal arts tradition of broad cross-disciplinary learning. These academics and educators included Robert Hutchins, Mortimer Adler, Stringfellow Barr, Scott Buchanan, Jacques Barzun, and Alexander Meiklejohn. The view among them was that the emphasis on narrow specialization in American colleges had harmed the quality of higher education by failing to expose students to the important products of Western civilization and thought.

The

essential component of such programs is a high degree of engagement

with primary texts, called the Great Books. The curricula of Great Books

programs often follow a canon of texts considered more or less

essential to a student’s education, such as Plato’s Republic, or Dante’s

Divine Comedy. Such programs often focus exclusively on Western

culture. Their employment of primary texts dictates an interdisciplinary

approach, as most of the Great Books do not fall neatly under the

prerogative of a single contemporary academic discipline. Great Books

programs often include designated discussion groups as well as lectures,

and have small class sizes. In general students in such programs

receive an abnormally high degree of attention from their professors, as

part of the overall aim of fostering a community of learning.

Over

100 institutions of higher learning, mostly in the United States, offer

some version of a Great Books Program as an option for students.[10]

There has been an ongoing debate, especially in the US, over the nature

and status of the canon since at least the 1960s, much of which is

rooted in critical theory, feminism, critical race theory, and Marxism.[3] In particular postmodern

studies has argued that the body of scholarship is biased, because the

main focus traditionally of the academic studies of history and Western culture, has only been on Europe and men. American philosopher Jay Stevenson argues:

Classicist Bernard Knox made direct reference to this topic when he delivered his 1992 Jefferson Lecture (the U.S. federal government’s highest honor for achievement in the humanities).[12] Knox used the intentionally “provocative” title “The Oldest Dead White European Males”,[13]

as the title of his lecture and his subsequent book of the same name,

in both of which Knox defended the continuing relevance of classical culture to modern society.[14] [15]

Some

intellectuals have championed a “high conservative modernism” that

insists that universal truths exist, and have opposed approaches that

deny the existence of universal truths.[16] Many argued that “natural law” was the repository of timeless truths.[17] Allan Bloom,

in his highly influential Closing of the American Mind: How Higher

Education Has Failed Democracy and Impoverished the Souls of Today’s

Students (1987) argues that moral degradation results from ignorance of

the great classics

that shaped Western culture. Bloom further comments: “But one thing is

certain: wherever the Great Books make up a central part of the

curriculum, the students are excited and satisfied.”[18]

His book was widely cited by some intellectuals for its argument that

the classics contained universal truths and timeless values which were

being ignored by cultural relativists.[19] [20] Yale University Professor of Humanities and famous literary critic Harold Bloom (no relation) has also argued strongly in favor of the canon, in his 1995 book The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages, and in general the canon remains as a represented idea in many institutions,[1] though its implications continue to be debated.

Defenders

maintain that those who undermine the canon do so out of primarily

political interests, and that such criticisms are misguided and/or

disingenuous. As John Searle, Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley, has written:

There

is a certain irony in this [i.e., politicized objections to the canon]

in that earlier student generations, my own for example, found the

critical tradition that runs from Socrates through the Federalist Papers, through the writings of Mill and Marx,

down to the twentieth century, to be liberating from the stuffy

conventions of traditional American politics and pieties. Precisely by

inculcating a critical attitude, the “canon” served to demythologize the

conventional pieties of the American bourgeoisie and provided the

student with a perspective from which to critically analyze American

culture and institutions. Ironically, the same tradition is now regarded

as oppressive. The texts once served an unmasking function; now we are

told that it is the texts which must be unmasked.[1]

One

of the main objections to a canon of literature is the question of

authority; who should have the power to determine what works are worth

reading? Searle’s rebuttal suggests that “one obvious difficulty with it

[i.e., arguments against hierarchical ranking of books] is that if it

were valid, it would argue against any set of required readings

whatever; indeed, any list you care to make about anything automatically

creates two categories, those that are on the list and those that are

not.”[1]

Charles Altieri, of the University of California, Berkeley,

states that canons are “an institutional form for exposing people to a

range of idealized attitudes.” It is according to this notion that work

may be removed from the canon over time to reflect the contextual

relevance and thoughts of society.[21] American historian Todd M. Compton

argues that canons are always communal in nature; that there are

limited canons for, say a literature survey class, or an English

department reading list, but there is no such thing as one absolute

canon of literature. Instead, there are many conflicting canons. He

regards Bloom’s “Western Canon” as a personal canon only.[22]

The process of defining the boundaries of the canon is endless. The philosopher John Searle

has said, “In my experience there never was, in fact, a fixed ‘canon’;

there was rather a certain set of tentative judgments about what had

importance and quality. Such judgments are always subject to revision,

and in fact they were constantly being revised.”[1] One of the notable attempts at compiling an authoritative canon for literature in the English-speaking world was the Great Books of the Western World program. This program, developed in the middle third of the 20th century, grew out of the curriculum at the University of Chicago. University president Robert Maynard Hutchins and his collaborator Mortimer Adler

developed a program that offered reading lists, books, and

organizational strategies for reading clubs to the general public. An

earlier attempt had been made in 1909 by Harvard University president Charles W. Eliot, with the Harvard Classics,

a 51-volume anthology of classic works from world literature. Eliot’s

view was the same as that of Scottish philosopher and historian Thomas Carlyle: “The true University of these days is a Collection of Books”. (”The Hero as Man of Letters”, 1840)

The

canon of Renaissance English poetry of the 16th and early 17th century

has always been in some form of flux and towards the end of the 20th

century the established canon was criticized, especially by those who

wished to expand it to include, for example, more women writers.[23] However, the central figures of the British renaissance canon remain, Edmund Spenser, Sir Philip Sidney, Christopher Marlowe, William Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, and John Donne.[24] Spenser, Donne, and Jonson were major influences on 17th-century poetry. However, poet John Dryden condemned aspects of the metaphysical poets in his criticism. In the 18th century Metaphysical poetry fell into further disrepute,[25] while the interest in Elizabethan poetry was rekindled through the scholarship of Thomas Warton and others. However, the canon of Renaissance poetry was formed in the Victorian period with anthologies like Palgrave’s Golden Treasury.[26]

In the twentieth century T. S. Eliot and Yvor Winters were two literary critics who were especially concerned with revising the canon of renaissance English literature. T. S. Eliot, for example, championed poet Sir John Davies in an article in The Times Literary Supplement in 1926. During the course of the 1920s, T.S. Eliot

did much to establish the importance of the metaphysical school, both

through his critical writing and by applying their method in his own

work. However, by 1961 A. Alvarez

was commenting that “it may perhaps be a little late in the day to be

writing about the Metaphysicals. The great vogue for Donne passed with

the passing of the Anglo-American experimental movement in modern

poetry.”[27] Two decades

later, a hostile view was expressed that emphasis on their importance

had been an attempt by Eliot and his followers to impose a ‘high

Anglican and royalist literary history’ on 17th-century English poetry.[28]

The American critic Yvor Winters suggested in 1939 an alternative canon of Elizabethan poetry,[29] which would exclude the famous representatives of the Petrarchan school of poetry, represented by Sir Philip Sidney and Edmund Spenser. Winters claimed that the Native or Plain Style anti-Petrarchan movement had been undervalued and argued that George Gascoigne (1525–1577) “deserves to be ranked […] among the six or seven greatest lyric poets of the century, and perhaps higher”.[30]

Towards the end of the 20th century the established canon was increasingly under fire.[31]

In the twentieth century there was a general reassessment of the literary canon, including women’s writing, post-colonial literatures, gay and lesbian literature,

writing by people of colour, working people’s writing, and the cultural

productions of historically marginalized groups. This reassessment has

resulted in a whole scale expansion of what is considered “literature”,

and genres hitherto not regarded as “literary”, such as children’s

writing, journals, letters, travel writing, and many others are now the

subjects of scholarly interest.[32] [33] [34]

The Western literary canon has also expanded to include the literature of Asia, Africa, the Middle East,

and South America. Writers from countries like Turkey, China, Egypt,

Peru, and Colombia, Japan, etc., have received Nobel prizes since the

late 1960s. Writers from Asia and Africa have also been nominated for,

and also won, the Booker prize in recent years.

The

feminist movement produced both feminist fiction and non-fiction and

created new interest in women’s writing. It also prompted a general

reevaluation of women’s historical

and academic contributions in response to the belief that women’s lives

and contributions have been underrepresented as areas of scholarly

interest.[32]

However,

in Britain and America at least women achieved major literary success

from the late eighteenth century, and many major nineteenth century

British novelists were women, including Jane Austen, the Brontë family, Mrs Gaskell, and George Eliot. There were also two major female poets, Elizabeth Barrett Browning[35] and Emily Dickinson.[36] [37] In the twentieth century there were also many major female writers, including Katherine Mansfield, Dorothy Richardson, Virginia Woolf, Eudora Welty, and Marianne Moore. Notable female writers in France include Colette and Simone de Beauvoir; and in Russia, Anna Akhmatova.

Much

of the early period of feminist literary scholarship was given over to

the rediscovery and reclamation of texts written by women. Virago Press

began to publish its large list of 19th and early 20th century novels

in 1975 and became one of the first commercial presses to join in the

project of reclamation.

In the twentieth century, the Western literary canon started to include black writers not only from black American writers, but also from the wider black diaspora

of writers in Britain, France, Latin America, and Africa. This is

largely due to the shift in social and political views during the civil rights movement in the United States. The first global recognition came in 1950 when Gwendolyn Brooks was the first black American to win a Pulitzer Prize for Literature. Chinua Achebe’s novel Things Fall Apart helped draw attention to African literature. Nigerian Wole Soyinka was the first African to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1986, and American Toni Morrison was the first black woman to win in 1993.

Throughout American history, African Americans have been discriminated against, and this experience inspired some Black writers,

at least during the early years, to prove they were the equals of white

American authors. As Henry Louis Gates, Jr., has said, “it is fair to

describe the subtext of the history of black letters as this urge to

refute the claim that because blacks had no written traditions they were

bearers of an inferior culture.”[38]

African-American

writers were also attempting to subvert the literary and power

traditions of the United States. Some scholars assert that writing has

traditionally been seen as “something defined by the dominant culture as

a white male activity.”[38]

This means that, in American society, literary acceptance has

traditionally been intimately tied in with the very power dynamics which

perpetrated such evils as racial discrimination. By borrowing from and

incorporating the non-written oral traditions and folk life of the African diaspora, African-American literature broke “the mystique of connection between literary authority and patriarchal power.”[39]

In producing their own literature, African Americans were able to

establish their own literary traditions devoid of the white intellectual

filter. This view of African-American literature as a tool in the

struggle for Black political and cultural liberation has been stated for

decades, most famously by W. E. B. Du Bois.[40]

Since

the 1960s the Western literary canon has been expanded to include

writers from Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and South America. This is

reflected in the Nobel prizes awarded in literature.

Yasunari Kawabata (1899 – 1972)[41] was a Japanese novelist and short story writer whose spare, lyrical, subtly-shaded prose works won him the Nobel Prize for Literature

in 1968, the first Japanese author to receive the award. His works have

enjoyed broad international appeal and are still widely read.

Naguib Mahfouz (1911 – 2006) was an Egyptian writer who won the 1988 Nobel Prize for Literature. He is regarded as one of the first contemporary writers of Arabic literature, along with Tawfiq el-Hakim, to explore themes of existentialism.[42]

He published 34 novels, over 350 short stories, dozens of movie

scripts, and five plays over a 70-year career. Many of his works have

been made into Egyptian and foreign films.

Kenzaburō Ōe (b. 1935) is a Japanese writer and a major figure in contemporary Japanese literature. His novels, short stories, and essays, strongly influenced by French and American literature and literary theory, deal with political, social, and philosophical issues, including nuclear weapons, nuclear power, social non-conformism, and existentialism. Ōe was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1994 for creating “an imagined world, where life and myth condense to form a disconcerting picture of the human predicament today”.[43]

Guan Moye

(b. 1955), better known by the pen name “Mo Yan”, is a Chinese novelist

and short story writer. Donald Morrison of the U.S. news magazine TIME referred to him as “one of the most famous, oft-banned and widely pirated of all Chinese writers“,[44] and Jim Leach called him the Chinese answer to Franz Kafka or Joseph Heller.[45] He is best known to Western readers for his 1987 novel Red Sorghum Clan, of which the Red Sorghum and Sorghum Wine volumes were later adapted for the film Red Sorghum. In 2012, Mo was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for his work as a writer “who with hallucinatory realism merges folk tales, history and the contemporary”.[46] [47]

Octavio Paz Lozano (1914 – 1998) was a Mexican poet and diplomat. For his body of work, he was awarded the 1981 Miguel de Cervantes Prize, the 1982 Neustadt International Prize for Literature, and the 1990 Nobel Prize in Literature.

Orhan Pamuk (b. 1952) is a Turkish novelist, screenwriter, academic, and recipient of the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature. One of Turkey’s most prominent novelists,[48] his work has sold over thirteen million books in sixty-three languages,[49] making him the country’s best-selling writer.[50] Pamuk is the author of novels including The White Castle, The Black Book, The New Life, My Name Is Red, Snow, The Museum of Innocence, and A Strangeness in My Mind. He is the Robert Yik-Fong Tam Professor in the Humanities at Columbia University, where he teaches writing and comparative literature. Born in Istanbul,[51]

Pamuk is the first Turkish Nobel laureate. He is also the recipient of

numerous other literary awards. My Name Is Red won the 2002 Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger, 2002 Premio Grinzane Cavour, and 2003 International Dublin Literary Award.

Gabriel García Márquez[52] (1927 – 2014) was a Colombian

novelist, short-story writer, screenwriter, and journalist. Considered

one of the most significant authors of the 20th century and one of the

best in the Spanish language, he was awarded the 1972 Neustadt International Prize for Literature and the 1982 Nobel Prize in Literature.[53]

García

Márquez started as a journalist, and wrote many acclaimed non-fiction

works and short stories, but is best known for his novels, such as One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967), The Autumn of the Patriarch (1975), and Love in the Time of Cholera

(1985). His works have achieved significant critical acclaim and

widespread commercial success, most notably for popularizing a literary

style labeled as magic realism,

which uses magical elements and events in otherwise ordinary and

realistic situations. Some of his works are set in a fictional village

called Macondo (the town mainly inspired by his birthplace Aracataca), and most of them explore the theme of solitude. On his death in April 2014, Juan Manuel Santos, the President of Colombia, described him as “the greatest Colombian who ever lived.”[54]

Mario Vargas Llosa, (b. 1936)[55] is a Peruvian writer, politician, journalist, essayist, college professor, and recipient of the 2010 Nobel Prize in Literature.[56]

Vargas Llosa is one of Latin America’s most significant novelists and

essayists, and one of the leading writers of his generation. Some

critics consider him to have had a larger international impact and

worldwide audience than any other writer of the Latin American Boom.[57] Upon announcing the 2010 Nobel Prize in Literature, the Swedish Academy

said it had been given to Vargas Llosa “for his cartography of

structures of power and his trenchant images of the individual’s

resistance, revolt, and defeat”.[58]

The

discussion of the literary canon above, especially with regard to

“Great Book” and the “debate” over the canon, is also relevant.

Ancient Greek philosophy

has consistently held a prominent place in the canon. Only a relatively

small number of works of Greek philosophy have survived, essentially

those thought most worth copying in the Middle Ages. Plato, Aristotle and, indirectly, Socrates are the primary figures. Roman philosophy is included, but regarded as less significant (as it tended to be even by the Romans themselves). The ancient philosophy of other cultures now receives more attention than before the 20th century. The vast body of Christian philosophy is typically represented on reading lists mainly by Saints Augustine of Hippo and Thomas Aquinas, and the 12th-century Jewish scholar Maimonides is now usually represented, mostly by The Guide for the Perplexed. The academic canon of early modern philosophy generally includes Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Locke, Berkeley, Hume, and Kant, though influential contributions to philosophy were made by many thinkers in this period.[59]

Women have engaged in philosophy throughout the field’s history. There were female philosophers since ancient times, notably Hipparchia of Maroneia (active c. 325 BC) and Arete of Cyrene (active 5th–4th century BC), and some were accepted as philosophers during the ancient, medieval, modern and contemporary eras, but almost no female philosophers have entered the philosophical Western canon.[60] [61] In the early 1990s, the Canadian Philosophical Association claimed that there is gender imbalance and gender bias in the academic field of philosophy.[62]

In June 2013, a US sociology professor stated that “out of all recent

citations in four prestigious philosophy journals, female authors

comprise just 3.6 percent of the total. While other areas of the

humanities are at or near gender parity, philosophy is actually more

overwhelmingly male than even mathematics.”[63]

Many philosophers today agree that Greek philosophy has influenced much of Western culture since its inception. Alfred North Whitehead once noted: “The safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.”[64] Clear, unbroken lines of influence lead from ancient Greek and Hellenistic philosophers to Early Islamic philosophy, the European Renaissance, and the Age of Enlightenment.[65] Some claim that Greek philosophy, in turn, was influenced by the older wisdom literature and mythological cosmogonies of the ancient Near East, but philosophy as we understand it is a Greek creation.”[66]

Plato was a philosopher in Classical Greece and the founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. He is widely considered the most pivotal figure in the development of philosophy, especially the Western tradition, unlike nearly all of his philosophical contemporaries.[67] [68]

Aristotle was an ancient Greek philosopher and scientist. His writings cover many subjects – including physics, biology, zoology, metaphysics, logic, ethics, aesthetics, poetry, theater, music, rhetoric, linguistics, politics and government—and constitute the first comprehensive system of Western philosophy.[69]

Aristotle’s views on physical science had a profound influence on medieval scholarship. Their influence extended from Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages into the Renaissance, and his views were not replaced systematically until the Enlightenment and theories such as classical mechanics. In metaphysics, Aristotelianism profoundly influenced Judeo-Islamic philosophical and theological thought during the Middle Ages and continues to influence Christian theology, especially the Neoplatonism of the Early Church and the scholastic tradition of the Roman Catholic Church. Aristotle was well known among medieval Muslim intellectuals and revered as “The First Teacher” (Arabic: المعلم الأول). His ethics, though always influential, gained renewed interest with the modern advent of virtue ethics. All aspects of Aristotle’s philosophy continue to be the object of active academic study today.[70]

Major Western writers and philosophers have been influenced by Eastern philosophy. American modernist poet T S Eliot wrote that the great philosophers of India “make most of the great European philosophers look like schoolboys”.[71] [72] Arthur Schopenhauer, in the preface to his book The World As Will And Representation,

writes that one who “has also received and assimilated the sacred

primitive Indian wisdom, then he is the best of all prepared to hear

what I have to say to him”[73] The 19th century American philosophical movement Transcendentalism was also influenced by Indian thought.[74] [75]

The seventeenth century was important for philosophy, and the major figures were Francis Bacon (1561–1626), Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), René Descartes (1596–1650), Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677), John Locke (1632–1704), Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716), and Isaac Newton (1642– c.1726).[76]

Major philosophers of the eighteenth century include George Berkeley (1685–1753), David Hume (1711–1776), Adam Smith (1723–1790), Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832), Voltaire (1694–1778), Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), and Edmund Burke (1729–1797).[77]

Important nineteenth century philosophers include Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831), Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855), Karl Marx (1818–1883) and Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900).

Major twentieth century figures are Henri Bergson (1859–1941), Edmund Husserl (1859-1938), Bertrand Russell (1872-1970), Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) and Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951). A porous distinction between analytic and continental approaches emerged during this period. The term “continental” is misleading, as many prominent British philosophers such as R. G. Collingwood and Michael Oakeshott were non-analytic, and many non-British European philosophers like Wittgenstein

were analytic. Moreover, analytic approaches are dominant in the

Netherlands, Scandinavia, Germany, and parts of east-central Europe

today. Some argue in English-speaking countries, it is better to

distinguish between the dominant approaches of university departments,

where Modern Language departments tend to favor continental methods and

philosophy department tends to favor analytic ones. However, the

humanities/social sciences departments in general such as history,

sociology, anthropology, and political science departments in

English-speaking countries tend to favor continental methods such as

those by Michel Foucault (1926-1984), Pierre Bourdieu (1930-2002) and Jürgen Habermas (1929- ).[78] [79]

Female

philosophers have begun to gain prominence in the last hundred years.

Notable female philosophers from the contemporary period include Susanne Langer (1895–1985), Simone de Beauvoir (1908–1986), and Martha Nussbaum (1947– ).

The term “classical music” did not appear until the early 19th century, in an attempt to distinctly canonize the period from Johann Sebastian Bach to Ludwig van Beethoven as a golden age. In addition to Bach and Beethoven, the other major figures from this period were Joseph Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.[80] The earliest reference to “classical music” recorded by the Oxford English Dictionary is from about 1836.[81]

In classical music,

during the nineteenth century a “canon” developed which focused on what

was felt to be the most important works written since 1600, with a

great concentration on the later part of this period, termed the Classical period, which is generally taken to begin around 1730. After Beethoven, the major nineteenth century composers include Robert Schumann, Frédéric Chopin, Hector Berlioz, Franz Liszt, Richard Wagner, Johannes Brahms, Anton Bruckner, Giuseppe Verdi, Giacomo Puccini, and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.[82]

In

the 2000s, the standard concert repertoire of professional orchestras,

chamber music groups, and choirs tends to focus on works by a relatively

small number of mainly 18th and 19th century male composers. Many of

the works deemed to be part of the musical canon are from genres

regarded as the most serious, such as the symphony, concerto, string quartet, and opera. Folk music was already giving art music melodies, and from the late 19th century, in an atmosphere of increasing nationalism,

folk music began to influence composers in formal and other ways,

before being admitted to some sort of status in the canon itself.

Since the early twentieth century non-Western music has begun to influence Western composers. In particular, direct homages to Javanese gamelan music are found in works for western instruments by Claude Debussy, Béla Bartók, Francis Poulenc, Olivier Messiaen, Pierre Boulez, Benjamin Britten, John Cage, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass.[83]

Debussy was immensely interested in non-Western music and its

approaches to composition. Specifically, he was drawn to the Javanese Gamelan,[84]

which he first heard at the 1889 Paris Exposition. He was not

interested in directly quoting his non-Western influences, but instead

allowed this non-Western aesthetic to generally influence his own

musical work, for example, by frequently using quiet, unresolved

dissonances, coupled with the damper pedal, to emulate the “shimmering”

effect created by a gamelan ensemble. American composer Philip Glass was not only influenced by the eminent French composition teacher Nadia Boulanger,[85] but also by the Indian musicians Ravi Shankar and Alla Rakha,

His distinctive style arose from his work with Shankar and Rakha and

their perception of rhythm in Indian music as being entirely additive.[86]

In the latter half of the 20th century the canon expanded to cover the so-called Early music of the pre-classical period, and Baroque music by composers other than Bach and George Frideric Handel. including Antonio Vivaldi, Claudio Monteverdi, Domenico Scarlatti, Alessandro Scarlatti, Henry Purcell, Georg Philipp Telemann, Jean-Baptiste Lully, Jean-Philippe Rameau, Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Arcangelo Corelli, François Couperin, Heinrich Schütz, and Dieterich Buxtehude. Earlier composers, such as Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, Orlande de Lassus and William Byrd, have also received more attention in the last hundred years.

The absence of female composers from the canon has been debated in the twentieth century, even though there have been female composers

throughout the classical music period. Marcia J Citron, for example,

has examined “the practices and attitudes that have led to the exclusion

of women [sic] composers from the received ‘canon’ of performed musical

works.”[87] More recently the music of Hildegard von Bingen (1098–1179), a German Benedictine abbess, has been rediscovered, and both the Russian Sofia Gubaidulina (1931– ) and Finnish Kaija Saariaho (1952– ) have achieved international reputations. Saariaho’s opera L’amour de loin has been staged in some of the world’s major opera houses, including The English National Opera (2009)[88] and in 2016 the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

The backbone of traditional Western art history is a celebratory chronology of artworks,

mostly of a luxury nature, commissioned by elite groups in western

Europe for private or public enjoyment, as well as works in drawing and printmaking. Much of this was religious, mostly Roman Catholic, art. The classical art

of Greece and Rome has been regarded since the Renaissance as the fount

of the Western tradition, and has been long regarded as superior to

modern creations in the equivalent fields, in particular sculpture.

Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574) is the great originator of the artistic canon and the originator of many of the concepts it embodies. His Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects covers only artists working in Italy,[89]

with a strong pro-Florentine prejudice, and has cast a long shadow over

succeeding centuries. Northern European art has arguably never quite

caught up to Italy in terms of prestige, and Vasari’s placing of Giotto as the founding father of “modern” painting has largely been retained. In painting, the rather vague term of Old master covers painters up to about the time of Goya.

Such

a “canon” remains prominent, as indicated by the selection of objects

present in art history textbooks, as well as the prices obtained in the art trade. But there have been considerable swings of fortune in what is valued. In the 19th century the Baroque fell into great disfavour, to be revived from about the 1920s, by which time the Academic art of the 18th and 19th century was largely disregarded, and Victorian painting generally, with its equivalents in other countries. The High Renaissance Vasari regarded as the greatest period has always retained its prestige, including works by Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael, but the succeeding period of Mannerism has fallen in and out of favour.

In

the 19th century the beginnings of academic art history, led by German

universities, led to much better understanding and appreciation of medieval art,

and a more nuanced understanding of classical art, including the

realization that many if not most treasured masterpieces of sculpture

were late Roman copies rather than Greek originals. The European

tradition of art was expanded to include Byzantine art and the new discoveries of archaeology, notably Etruscan art, Celtic art and Upper Paleolithic art.

Since

the 20th century there has been an effort to re-define the discipline

to be more inclusive of art made by women; vernacular creativity,

especially in printed media; and an expansion to include works in the

Western tradition produced outside Europe. At the same time there has

been a much greater appreciation of non-Western traditions, including

their place with Western art in wider global or Eurasian traditions. The decorative arts have traditionally had a much lower critical status than fine art,

although often highly valued by collectors, and still tend to be given

little prominence in undergraduate studies or popular coverage on

television and in print.

Women

were discriminated against in terms of obtaining the training necessary

to be an artist in the mainstream Western traditions. In addition,

since the Renaissance the nude, more often than not female, has had a special position as subject matter. In her 1971 essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?“, Linda Nochlin

analyzes what she sees as the embedded privilege in the predominantly

male Western art world and argues that women’s outsider status allowed

them a unique viewpoint to not only critique women’s position in art,

but to additionally examine the discipline’s underlying assumptions

about gender and ability.[90]

Nochlin’s essay develops the argument that both formal and social

education restricted artistic development to men, preventing women (with

rare exception) from honing their talents and gaining entry into the

art world.[90]

In

the 1970s, feminist art criticism continued this critique of the

institutionalized sexism of art history, art museums, and galleries, and

questioned which genres of art were deemed museum-worthy.[91] This position is articulated by artist Judy Chicago:

“[I]t is crucial to understand that one of the ways in which the

importance of male experience is conveyed is through the art objects

that are exhibited and preserved in our museums. Whereas men experience

presence in our art institutions, women experience primarily absence,

except in images that do not necessarily reflect women’s own sense of

themselves.”[92]

English artist and sculptor Barbara Hepworth DBE (1903 – 1975), whose work exemplifies Modernism, and in particular modern sculpture, is one of the few female artists to achieve international prominence.[93] In 2016 the art of American modernist Georgia O’Keefe has been staged at the Tate Modern, in London, and is then moving in December 2016 to Vienna, Austria, before visiting the Art Gallery of Ontario, Canada in 2017.[94]

The preface to the Blackwell

anthology of Renaissance Literature from 2003 acknowledges the

importance of online access to literary texts on the selection of what

to include, meaning that the selection can be made on basis of

functionality rather than representativity”.[99]

This anthology has made its selection based on three principles. One is

“unabashedly canonical”, meaning that Sidney, Spenser, Marlowe,

Shakespeare, and Jonson have been given the space prospective users

would expect. A second principle is “non-canonical”, giving female

writers such as Anne Askew, Elizabeth Cary, Emilia Lanier, Martha Moulsworth, and Lady Mary Wroth

a representative selection. It also includes texts that may not be

representative of the qualitatively best efforts of Renaissance

literature, but of the quantitatively most numerous texts, such as

homilies and erotica. A third principle has been thematic, so that the

anthology aims to include texts that shed light on issues of special

interest to contemporary scholars.

The Blackwell anthology is

still firmly organised around authors, however. A different strategy has

been observed by The Penguin Book of Renaissance Verse from 1992.[100]

Here the texts are organised according to topic, under the headings The

Public World, Images of Love, Topographies, Friends, Patrons and the

Good Life, Church, State and Belief, Elegy and Epitaph, Translation,

Writer, Language and Public. It is arguable that such an approach is

more suitable for the interested reader than for the student. While the

two anthologies are not directly comparable, since the Blackwell

anthology also includes prose and the Penguin anthology goes up to 1659,

it is telling that while the larger Blackwell anthology contains work

by 48 poets, seven of which are women, the Penguin anthology contains

374 poems by 109 poets, including 13 women and one poet each in Welsh, Siôn Phylip, and Irish, Eochaidh Ó Heóghusa.

The Best German Novels of the Twentieth Century is a list of books compiled in 1999 by Literaturhaus München and Bertelsmann, in which 99 prominent German authors, literary critics, and scholars of German ranked the most significant German-language novels of the twentieth century.[101] The group brought together 33 experts from each of the three categories.[102]

Each was allowed to name three books as having been the most important

of the century. Cited by the group were five titles by both Franz Kafka and Arno Schmidt, four by Robert Walser, and three by Thomas Mann, Hermann Broch, Anna Seghers, and Joseph Roth.[101]

Der Kanon or more precisely “Marcel-Reich-Ranickis Kanon” is a large anthology of exemplary works of German literature.[103]

See Key texts of French literature

The Canon of Dutch Literature comprises a list of 1000 works of Dutch Literature important to the cultural heritage of the Low Countries, and is published on the DBNL.

Several of these works are lists themselves; such as early

dictionaries, lists of songs, recipes, biographies, or encyclopedic

compilations of information such as mathematical, scientific, medical,

or plant reference books. Other items include early translations of

literature from other countries, history books, first-hand diaries, and

published correspondence. Notable original works can be found by author

name.

The Danish Culture Canon consists of 108 works of cultural excellence in eight categories: architecture, visual arts, design and crafts, film, literature, music, performing arts, and children’s culture. An initiative of Brian Mikkelsen in 2004, it was developed by a series of committees under the auspices of the Danish Ministry of Culture

in 2006–2007 as “a collection and presentation of the greatest, most

important works of Denmark’s cultural heritage.” Each category contains

12 works, although music contains 12 works of score music and 12 of

popular music, and the literature section’s 12th item is an anthology of

24 works.[104] [105]

Världsbiblioteket (The World Library) was a Swedish list of the 100 best books in the world, created in 1991 by the Swedish literary magazine Tidningen Boken. The list was compiled through votes from members of the Svenska Akademien, Swedish Crime Writers’ Academy, librarians, authors, and others. Approximately 30 of the books were Swedish.

|

Julie Nurchi Litterature |

FAVE

|

|

|

||

|

|

||