For The Welfare, Happiness, Peace of All Sentient and Non-Sentient Beings and for them to Attain Eternal Peace as Final Goal.

KUSHINARA NIBBANA BHUMI PAGODA-It

At

WHITE HOME

668, 5A main Road, 8th Cross, HAL III Stage, Prabuddha Bharat Puniya Bhumi Bengaluru

Magadhi Karnataka State PRABUDDHA BHARAT

Please Visit and post to: https://www.buddha-vacana.org/ in 29) Classical English,Roman,101) Classical Tamil-பாரம்பரிய இசைத்தமிழ் செம்மொழி,54) Classical Kannada- ಶಾಸ್ತ್ರೀಯ ಕನ್ನಡ,06) Classical Devanagari,Classical Hindi-Devanagari- शास्त्रीय हिंदी,72) Classical Marathi-क्लासिकल माओरी,69) Classical Malayalam-ക്ലാസിക്കൽ മലയാളം,77) Classical Odia (Oriya),82) Classical Punjabi-ਕਲਾਸੀਕਲ ਪੰਜਾਬੀ,

is a 18 feet Dia All White Pagoda with a table or, but be sure

to having above head level based on the usual use of the room. in

116 CLASSICAL LANGUAGES and planning to project Therevada Tipitaka in Buddha’s own words and Important Places like

Lumbini, Bodh gaya, Saranath, Kushinara, Etc., in 3D 360 degree circle vision akin

to Circarama

a just born baby is kept isolated without anyone communicating with the

baby, after a few days it will speak and human natural (Prakrit)

language known as Classical Magahi Magadhi/Classical Chandaso language/

which are the same. Buddha spoke in Magadhi. All the 7111 languages and

dialects are off shoot of Classical Magahi Magadhi. Hence all of them

are Classical in nature (Prakrit) of Human Beings, just like all other

living speices have their own naturallanguages for communication. 116

languages are translated by

https://translate.google.com

https://www.buddha-vacana.org/

bhikkhus, you should train thus: ‘We will listen to the utterance of

such discourses which are words of the Tathāgata, profound, profound in

meaning, leading beyond the world, (consistently) connected with

emptiness, we will lend ear, we will apply our mind on knowledge, we

will consider those teachings as to be taken up and mastered.’ This is

how, bhikkhus, you should train yourselves said the Buddha

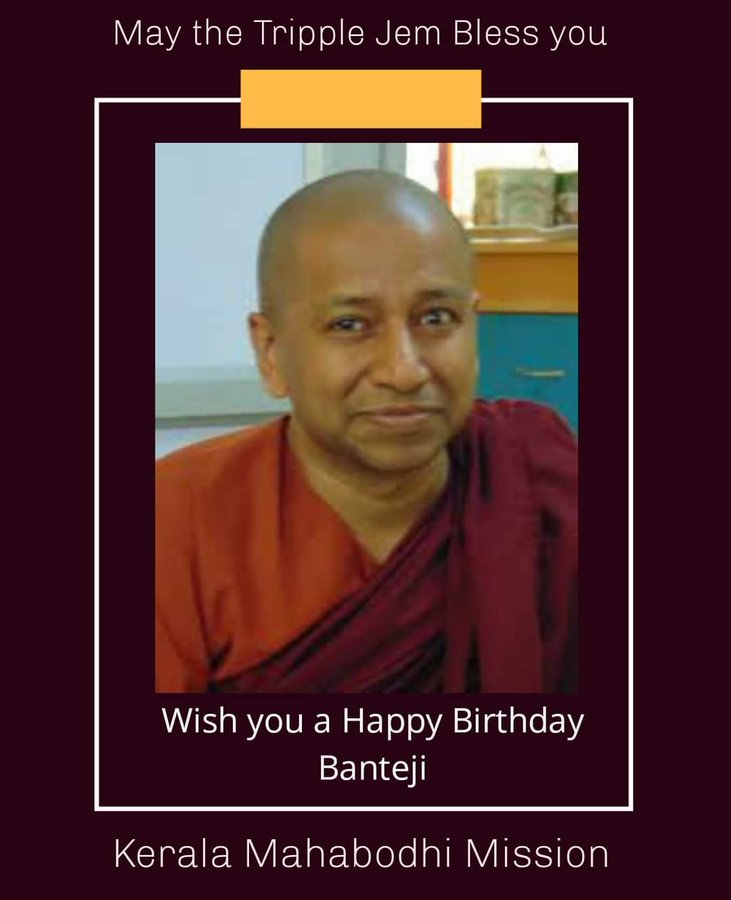

many happy returns of the day Venerable AnandaBhante Ji. From J

Chandrasekharan, Mrs. Navaneetham, Banu Rekha Pradeep Kumar, Sashi

Kanth, Shifu, Harshith, Pranay,Vinay. We are practising Theravada

Tipitaka as directed by your honourable self.

https://www.buddha-vacana.org/

54) Classical Kannada- ಶಾಸ್ತ್ರೀಯ ಕನ್ನಡ,

ಆದ್ದರಿಂದ,

ಭಿಕ್ಷುಸ್, ನೀವು ಹೀಗೆ ತರಬೇತಿ ನೀಡಬೇಕು: ‘ನಾವು ತಥಾಗತದ ಪದಗಳು, ಆಳವಾದ,

ಅರ್ಥದಲ್ಲಿ ಆಳವಾದ, ಜಗತ್ತನ್ನು ಮೀರಿ ಮುನ್ನಡೆಸುವ, (ಸತತವಾಗಿ) ಖಾಲಿತನದೊಂದಿಗೆ

ಸಂಪರ್ಕ ಹೊಂದಿದ ಇಂತಹ ಪ್ರವಚನಗಳನ್ನು ನಾವು ಕೇಳುತ್ತೇವೆ, ನಾವು ಕಿವಿ ಸಾಲ

ನೀಡುತ್ತೇವೆ, ನಾವು ಜ್ಞಾನದ ಮೇಲೆ ನಮ್ಮ ಮನಸ್ಸನ್ನು ಅನ್ವಯಿಸುತ್ತದೆ, ನಾವು ಆ ಬೋಧನೆಗಳನ್ನು ಕೈಗೆತ್ತಿಕೊಂಡು ಮಾಸ್ಟರಿಂಗ್ ಎಂದು ಪರಿಗಣಿಸುತ್ತೇವೆ. ‘ ಈ ರೀತಿ, ಭಿಕ್ಷುಸ್, ನೀವೇ ತರಬೇತಿ ನೀಡಬೇಕು.

101) Classical Tamil-பாரம்பரிய இசைத்தமிழ் செம்மொழி,

ஆகையால்,

பிக்குகளே, நீங்கள் இவ்வாறு பயிற்சியளிக்க வேண்டும்: ‘இதுபோன்ற

சொற்பொழிவுகளின் சொற்களை நாங்கள் கேட்போம், அவை ததகதாவின் சொற்கள்,

ஆழமானவை, அர்த்தத்தில் ஆழமானவை, உலகத்தைத் தாண்டி வழிநடத்துகின்றன,

(தொடர்ந்து) வெறுமையுடன் இணைக்கப்பட்டுள்ளன, நாங்கள் காது கொடுப்போம், அறிவின் மீது நம் மனதைப் பயன்படுத்துவோம், அந்த போதனைகளை எடுத்துக்கொள்வதற்கும் தேர்ச்சி பெறுவதற்கும் நாங்கள் கருதுவோம். ‘ இப்படித்தான், பிக்குகளே, நீங்களே பயிற்சி பெற வேண்டும்.

06) Classical Devanagari,Classical Hindi-Devanagari- शास्त्रीय हिंदी,

https://www.buddha-vacana.org/

इसलिए, भिक्खु, आपको इस प्रकार प्रशिक्षित करना चाहिए: ‘हम ऐसे प्रवचनों के उच्चारण के बारे में सुनेंगे जो ताथागट्टा शब्द हैं, गहरा, अर्थ में गहरा, दुनिया से परे, (लगातार) शून्यता से जुड़ा हुआ, हम कान उधार देंगे, हम हमारे दिमाग को ज्ञान पर लागू करेंगे, हम उन शिक्षाओं को अपनाएंगे और महारत हासिल करेंगे। ‘ यह है, कैसे, आप अपने आप को प्रशिक्षित करना चाहिए।

72) Classical Marathi-क्लासिकल माओरी,

https://www.buddha-vacana.org/

म्हणून, भिख्खूस, तुम्ही असे प्रशिक्षण घ्यावे: ‘आम्ही अशा प्रवचनांचे ऐकून घेऊया जे तागतगताचे शब्द आहेत, सखोल, प्रगल्भ, जगाच्या पलीकडे अग्रगण्य आहेत, (सतत) शून्यतेने जोडलेले आहेत, आपण कान देऊ, आपले ज्ञान ज्ञानावर लागू करेल, त्या शिकवण्या आपण स्वीकारल्या पाहिजेत आणि त्या मानल्या पाहिजेत. ‘ अशा प्रकारे, भिख्खूस, तुम्ही स्वतःला प्रशिक्षित केले पाहिजे.

69) Classical Malayalam-ക്ലാസിക്കൽ മലയാളം,

https://www.buddha-vacana.org/

അതിനാൽ, ഭിക്ഷുമാരേ, നിങ്ങൾ ഇങ്ങനെ പരിശീലിപ്പിക്കണം: ‘തത്തഗതയുടെ വാക്കുകൾ, അഗാധമായ, അർത്ഥത്തിൽ അഗാധമായ, ലോകത്തിനപ്പുറത്തേക്ക് നയിക്കുന്ന, (സ്ഥിരമായി) ശൂന്യതയുമായി ബന്ധപ്പെട്ടിരിക്കുന്ന അത്തരം പ്രഭാഷണങ്ങളുടെ ഉച്ചാരണം ഞങ്ങൾ കേൾക്കും, ഞങ്ങൾ ചെവി നൽകും, ഞങ്ങൾ അറിവിൽ നമ്മുടെ മനസ്സ് പ്രയോഗിക്കും, ആ പഠിപ്പിക്കലുകൾ ഏറ്റെടുക്കാനും പ്രാവീണ്യം നേടാനും ഞങ്ങൾ പരിഗണിക്കും. ‘ ഇങ്ങനെയാണ്, ഭിക്ഷുക്കളേ, നിങ്ങൾ സ്വയം പരിശീലിപ്പിക്കണം.

77) Classical Odia (Oriya),

https://www.buddha-vacana.org/

ତେଣୁ, ଭିକ୍କସ୍, ତୁମେ ଏହିପରି ତାଲିମ ଦେବା ଉଚିତ୍: ‘ଆମେ ଏପରି ବକ୍ତବ୍ୟର ଉଚ୍ଚାରଣକୁ ଶୁଣିବା, ଯାହା ଟାଥଗାଟାର ଶବ୍ଦ, ଗଭୀର, ଅର୍ଥର ଗଭୀର, ବିଶ୍ beyond ର ବାହାରେ, (କ୍ରମାଗତ ଭାବରେ) ଶୂନ୍ୟତା ସହିତ ଜଡିତ, ଆମେ କାନ end ଣ ଦେବୁ, ଆମେ ଜ୍ଞାନ ଉପରେ ଆମର ମନ ପ୍ରୟୋଗ କରିବ, ଆମେ ସେହି ଶିକ୍ଷାଗୁଡ଼ିକୁ ଗ୍ରହଣ କରାଯିବ ଏବଂ ବିଚାର କରିବୁ ବୋଲି ବିଚାର କରିବୁ। ଏହିପରି, ଭିକ୍କସ୍, ତୁମେ ନିଜକୁ ତାଲିମ ଦେବା ଉଚିତ୍ |

82) Classical Punjabi-ਕਲਾਸੀਕਲ ਪੰਜਾਬੀ,

https://www.buddha-vacana.org/

ਇਸ ਲਈ, ਭਿੱਖੁਸ, ਤੁਹਾਨੂੰ ਇਸ ਤਰ੍ਹਾਂ ਸਿਖਲਾਈ ਦੇਣੀ ਚਾਹੀਦੀ ਹੈ: ‘ਅਸੀਂ ਇਸ ਤਰ੍ਹਾਂ ਦੇ ਭਾਸ਼ਣ ਸੁਣਾਂਗੇ ਜੋ ਤੱਤਗੱਤੇ ਦੇ ਸ਼ਬਦ ਹਨ, ਅਰਥਾਂ ਵਿਚ ਡੂੰਘੇ, ਡੂੰਘੇ, ਸੰਸਾਰ ਤੋਂ ਪਰ੍ਹੇ, (ਨਿਰੰਤਰ) ਖਾਲੀਪਨ ਨਾਲ ਜੁੜੇ ਹੋਏ, ਅਸੀਂ ਕੰਨ ਉਤਾਰਾਂਗੇ, ਅਸੀਂ ਗਿਆਨ ‘ਤੇ ਆਪਣਾ ਮਨ ਲਾਗੂ ਕਰਾਂਗੇ, ਅਸੀਂ ਉਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਉਪਦੇਸ਼ਾਂ’ ਤੇ ਵਿਚਾਰ ਕਰਾਂਗੇ ਜਿਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਅਪਣਾਇਆ ਅਤੇ ਮਾਹਰ ਬਣਾਇਆ ਗਿਆ ਹੈ. ‘ ਇਸ ਤਰ੍ਹਾਂ, ਭਿੱਖੁਸ, ਤੁਹਾਨੂੰ ਆਪਣੇ ਆਪ ਨੂੰ ਸਿਖਲਾਈ ਦੇਣੀ ਚਾਹੀਦੀ ਹੈ.

86) Classical Sanskrit छ्लस्सिचल् षन्स्क्रित्,

86) छ्लस्सिचल् षन्स्क्रित् छ्लस्सिचल् षन्स्क्रित्

ह्त्त्प्सः//www.बुद्ध-वचन.ओर्ग्/

— Āṇइ षुत्त —

ठेरेfओरे, भिक्खुस्, योउ स्होउल्द् त्रैन् थुसः ‘Wए wइल्ल् लिस्तेन् तो थे उत्तेरन्चे ओf सुच्ह् दिस्चोउर्सेस् wहिच्ह् अरे wओर्द्स् ओf थे टथ्āगत, प्रोfओउन्द्, प्रोfओउन्द् इन् मेअनिन्ग्, लेअदिन्ग् बेयोन्द् थे wओर्ल्द्, (चोन्सिस्तेन्त्ल्य्) चोन्नेच्तेद् wइथ् एम्प्तिनेस्स्, wए wइल्ल् लेन्द् एअर्, wए wइल्ल् अप्प्ल्य् ओउर् मिन्द् ओन् क्नोwलेद्गे, wए wइल्ल् चोन्सिदेर् थोसे तेअच्हिन्ग्स् अस् तो बे तकेन् उप् अन्द् मस्तेरेद्.’ ठिस् इस् होw, भिक्खुस्, योउ स्होउल्द् त्रैन् योउर्सेल्वेस् सैद् थे Bउद्ध

- Āṇ سٽا -

تنهن ڪري ، ڀاخس ، توهان کي اهڙيءَ طرح تربيت ڪرڻ گهرجي: ‘اسان اهڙن خيالن جو ويچار ٻڌندا سين ، جيڪي تاتهاگ جا لفظ آهن ، معنى ۾ گہرے ، گہرے معنيٰ ۾ ، دنيا کان اڳتي هلي رهيا آهن ، (مسلسل) خالي سان ڳن connectedيل آهن ، اسان ڪن قرض ڏينداسين ، اسان جي دماغ علم تي لاڳو ڪنداسين ، اسان انهن تعليمات تي غور ڪيو ويندو جيئن انهن کي وٺڻ ۽ بهتر هئڻ گهرجي. شيخ ، توهان کي پاڻ کي تربيت ڏيڻ گهرجي.

- Āṇi సుత్తా -

అందువల్ల, భిక్షువులారా, మీరు ఈ విధంగా శిక్షణ ఇవ్వాలి: ‘తథాగట యొక్క పదాలు, లోతైనవి, అర్థంలో లోతైనవి, ప్రపంచానికి మించినవి, (స్థిరంగా) శూన్యతతో అనుసంధానించబడినవి, మేము చెవికి అప్పు ఇస్తాము, జ్ఞానంపై మన మనస్సును వర్తింపజేస్తుంది, మేము ఆ బోధలను స్వాధీనం చేసుకుని, ప్రావీణ్యం పొందినట్లుగా భావిస్తాము. ‘ ఈ విధంగా, భిక్షూస్, మీరు మీరే శిక్షణ పొందాలి.

- Si سوٹا -

لہذا ، بھکھوس ، آپ کو اس طرح کی تربیت دی جانی چاہئے: ‘ہم اس طرح کے تقاریر کی بات کو سنیں گے جو تتگاتا کے الفاظ ہیں ، گہرا ، گہرا معنی میں ، دنیا سے آگے کی طرف جانے والے ، (مستقل طور پر) خالی پن کے ساتھ جڑے ہوئے ہیں ، ہم کان دھاریں گے ، ہم علم پر اپنا ذہن استعمال کریں گے ، ہم ان تعلیمات پر عمل پیرا ہوں گے اور اس میں مہارت حاصل کریں گے۔ ‘ اس طرح ، بھکھوس ، آپ کو اپنی تربیت کرنی چاہئے۔

- আই সুতা -

অতএব, ভখখুস, আপনার এই প্রশিক্ষণ দেওয়া উচিত: ‘আমরা এই জাতীয় বক্তৃতাগুলি শুনব যা তত্ত্বগঠনের শব্দ, গভীর, অর্থপূর্ণভাবে গভীর, বিশ্বকে ছাড়িয়ে এগিয়ে চলেছে, (ধারাবাহিকভাবে) শূন্যতার সাথে সংযুক্ত, আমরা কান ধার দেব, আমরা জ্ঞানের উপর আমাদের মন প্রয়োগ করবে, আমরা সেই শিক্ষাগুলি গ্রহণ ও দক্ষ হিসাবে বিবেচনা করব ‘’ এইভাবে, ভিখখুস, আপনার নিজের প্রশিক্ষণ দেওয়া উচিত।

- Si સુત્તા -

તેથી, ભિખ્ખુસ, તમારે આ રીતે તાલીમ લેવી જોઈએ: ‘અમે આવા પ્રવચનોની વાતો સાંભળીશું, જે તાગગતનાં શબ્દો છે, ગહન, અર્થમાં ગહન, વિશ્વની બહાર દોરી જાય છે, (સતત) ખાલીપણું સાથે જોડાયેલા છે, આપણે કાન ઉધારીશું, આપણે જ્ knowledgeાન પર આપણા મનનો ઉપયોગ કરીશું, અમે તે ઉપદેશોને ધ્યાનમાં લેવામાં અને માસ્ટર કરવામાં આવશે. ‘ આ રીતે, ભિખુસ, તમારે પોતાને તાલીમ આપવી જોઈએ.

to YouTube by The state51 Conspiracy Tripitaka Song · Soothing Music

Ensamble Buddha Zen Music Masters Collection: Soothing Music for Sleep

Academy …

![]()

Chanting has helped many people to become peace, calm and tranquil,

build mindfulness while listening and/or chant attentively, re-gain

confidence from fear and uncertainty, bring happiness and positive

energy for those who are in sick and those in their last moment in this

very life (as hearing is thought to be the last sense to go in the dying

process). May you get the benefits of this chanting too.

compilation consists of Recollection of Buddha (Buddhanusati or

Itipiso), Recollection of Dhamma (Dhammanusati), Recollection of Sangaha

(Sanghanusati), Mangala Sutta, Ratana Sutta, Karaniya Metta Sutta,

Khandha Sutta, Bhaddekaratta Gatha, Metta Chant, Accaya Vivarana,

Vandana, Pattanumodana, Devanumodana, Punnanumodana and Patthana.

compilation is made possible by Venerable Samanera Dhammasiri getting

the permission from Venerable Vajiradhamma Thera to compile and

distribute, and co-edit and proofing. The background image is photo

taken by Venerable Dhammasubho. First compilation completed in 2007 and

further edit was done in 2015. Thanks and Sadhu to all who have assisted

and given me the opportunity to do this compilation especially my

family. May the merits accrue from this compilation share with all. With

Metta, Tissa Ng.

| Buddhism and Music An introduction to the musical practices of Buddhism in Sri Lanka, Myanmar (Burma), Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Indonesia, Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan, China, Mongolia, Korea, and Japan* N.B. If you hear several music clips playing simultaneously, try opening this website in Firefox. |

What is Buddhism? What is Buddhism? The term “Buddhism” describes a set of religious traditions that have developed across Asia and parts of the rest of the world over the past 2,500 years, originating with Siddhartha Gautama (ca. 563 to 483 BC), who was revered as the Buddha–the enlightened or awakened one–by his disciples. Buddhism has spread through many Asian cultures and has been altered and adapted according to local custom; as a result, its diversity is one of its hallmarks. This diversity makes it difficult sometimes to recognize similarities from one extreme of Buddhist practice to another, but all practices and practitioners share some points in common. Who was the Buddha? The Buddha’s teachings (Dharma). The Four Noble Truths.

1. The truth of suffering or dukkha [that all life is filled with

suffering]. 2. The truth of the origin of suffering [that desire, or tanha, causes suffering]. 3· The truth of the cessation of suffering [that it is necessity to let go of desire]. 4· The truth of the Path [that there is a way to achieve enlightenment or nirvana].

The Noble Eightfold Path.

Enlightenment, Nirvana, and Karma: Impermanence, Suffering, and Non-Identity.

The importance of impermanence in Buddhism makes the performance of The followers of Buddha. Three early schools of Buddhism. Theravada Buddhism vs. Mahayana Buddhism. The Three Jewels of Buddhism: Buddha, Dhamma, and Sangha. ) |

| Early negative attitudes toward music. Theravada Buddhists regard music as a type of sensual luxury, and their tradition notes that music should be approached only with great caution. Among the Ten Precepts accepted upon entering monastic life, the seventh requires the monk to avoid dancing, singing, music, and entertainments, and to abstain from wearing garlands, perfume, or cosmetics. The risk regarding music and singing is that one might focus on the musical quality of the voice rather than on the teachings enunciated in the song or chant. The Buddha himself is said to have avoided attending musical performances, and cautions his disciples about musical chant: “0 monks, there are five disadvantages for one singing the teaching in an extended sung intonation. (1) He is attached to himself regarding that sound;

(2) and others are attached to that sound; (3) and even householders are irritated. (4) There is dissolution of concentration on the part of one straining to lock in on the sound; and (5) people who follow after [this procedure] undergo an adherence to opinions.”

The musical reality of Buddhist practice.

To

the Buddha for refuge I go To the Dharma for refuge I go To the Sangha for refuge I go For the second time to the Buddha for refuge I go For the second time to the Dharma for refuge I go For the second time to the Sangha for refuge I go For the third time to the Buddha for refuge I go For the third time to the Dharma for refuge I go For the third time to the Sangha for refuge I go.

I

undertake to abstain from taking life I undertake to abstain from taking the not-given I undertake to abstain from sexual misconduct I undertake to abstain from false speech I undertake to abstain from taking intoxicants

Buddhist chant.

This

craving, which should be eliminated, is the Noble Truth of the origin of suffering, which monks should know. Concerning things unheard of before, there arose in me vision, knowledge, understanding; there arose in me wisdom; there arose in me penetrative insight and light.

May

all blessings be yours; May all gods protect you. By the power of all Buddhas May all happiness be yours. May all blessings be yours; May all gods protect you. By the power of all Dharmas May all happiness be yours. May all blessings be yours; May all gods protect you. By the power of all the Sangha May all happiness be yours. The Role of chant in monasteries. Different musical approaches to Buddhist chant. Chant in the vernacular.

Music and movement. The chanting of sacred sound-formulas (mantras). Mahayana Buddhism is

The musical world of Buddhism.

Each

stupa and temple is adorned with a thousand curtains and banners circling around and wrought with gems, and jeweled bells which harmoniously chime. All the gods, dragons, and spirits, humans and non-humans, with incense, flowers, and instrumental music, constantly make offerings.

At

that time, Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva said to Sakyamuni Buddha, “Honored of the World, let me now declare how human beings in the future will acquire great benefit and happiness, during their lifetime and at the moment of their death. I anticipate you to be congenial enough to listen to me.” Sakyamuni Buddha then disclosed to Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva, “It is because of your compassionate Infinite Loving Kindness that you long to assert about a possible tendency of relieving all the erring beings from the six States of reincarnation. Of course, it is the proper time now. Please speak promptly as I am about to enter Nibbana. I wish to bless you with success in discharging the strong vow so that I shall have no worry about human beings in the future.” Ksitigarbha . . . . . . . . . .

Honored of the If others can chant

|

The spread of Buddhism across Asia. From its birthplace in Northern India, Buddhism began to spread through South Asia, Southeast Asia, Indonesia, the Far East, and, eventually, the rest of the world. During the time of the Mauryan emperor Ashoka, who was a public supporter of the religion, and his descendants, stupas (Buddhist religious memorials) were built and efforts made to spread Buddhism throughout the enlarged Maurya empire and even into neighboring lands—particularly to the Iranian-speaking regions of Afghanistan and Central Asia, beyond the Mauryas’ northwest border, and to the island of Sri Lanka south of India. These two missions, in opposite directions, would ultimately lead, in the first case to the spread of Buddhism into China, and in the second case, to the emergence of Theravada Buddhism and its spread from Sri Lanka to the coastal lands of Southeast Asia. This period marks the first known spread The gradual spread of Buddhism into adjacent areas meant that it came The Theravada school spread The Silk Road transmission of

|

|

Regional musical practices. To find out more about musical practices of Buddhism in Sri Lanka, Myanmar (Burma), Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Indonesia, Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan, China, Mongolia, Korea, and Japan: you can either (1) click on the above links, or, which is infinitely more cool, (2) click on the below thumbnail map of South Asia, Southeast Asia, and East Asia. This will bring up a bitmap with “hot spots,” in which you may

(click on thumbnail map)

|

| *This introduction to Buddhism is taken from Sean Williams, “Buddhism and Music” in Sacred Sound: Experiencing Music in World Religions, Guy Beck, ed. Wilfred Laurier University Press (2006), pp.169-189. Much of the information on the following webpages is taken from The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: Volume 4: Southeast Asia - ed. Terry E. Miller (Professor Emeritus of Ethnomusicology. Kent State University) and Sean Williams (Evergreen State College) 1998; Volume 5: South Asia: The Indian Subcontinent - ed. Alison Arnold (North Carolina State University) 1999; Volume 7: East Asia: China, Japan, and Korea - ed. Robert Provine, (Professor of Ethnomusicology, University of Maryland) 2001. A more extensive bibliography is Paul D. Greene, Keith Howard, Terry E. Miller, Phong T. Nguyen and Hwee-San Tan, “Buddhism and the Musical Cultures of Asia: A Critical Literature Survey,” in The World of Music,Vol. 44, No. 2, Body and Ritual in Buddhist Musical Cultures (2002), 135-175 (VWB - Verlag für Wissenschaft und Bildung, 2002; available on JSTOR). |

https://www.buddha-vacana.org/

05) Classical Pāḷi

|

Bhavissanti 29) Classical English,Roman time, there will be bhikkhus who will not listen to the utterance of such discourses which are words of the Tathāgata, profound, profound in meaning, leading beyond the world, (consistently) connected with emptiness, they will not lend ear, they will not apply their mind on knowledge, they will not consider those teachings as to be taken up and mastered. |

Ye pana te suttantā kavi·katā kāveyyā citta·kkharā citta·byañjanā bāhirakā sāvaka·bhāsitā,

tesu bhaññamānesu sussūsissanti, sotaṃ odahissanti, aññā cittaṃ

upaṭṭhāpessanti, te ca dhamme uggahetabbaṃ pariyāpuṇitabbaṃ maññissanti.

On the contrary, they will listen to the utterance of

such discourses which are literary compositions made by poets, witty

words, witty letters, by people from outside, or the words of disciples,

they will lend ear, they will apply their mind on knowledge, they will

consider those teachings as to be taken up and mastered.

Evam·etesaṃ, bhikkhave,

suttantānaṃ tathāgata·bhāsitānaṃ gambhīrānaṃ gambhīr·atthānaṃ

lok·uttarānaṃ suññata·p·paṭisaṃyuttānaṃ antaradhānaṃ bhavissati.

Thus, bhikkhus, the discourses which are words of the

Tathāgata, profound, profound in meaning, leading beyond the world,

(consistently) connected with emptiness, will disappear.

Tasmātiha,

bhikkhave, evaṃ sikkhitabbaṃ: ‘ye te suttantā tathāgata·bhāsitā gambhīrā

gambhīr·atthā lok·uttarā suññata·p·paṭisaṃyuttā, tesu bhaññamānesu

sussūsissāma, sotaṃ odahissāma, aññā cittaṃ upaṭṭhāpessāma, te ca dhamme

uggahetabbaṃ pariyāpuṇitabbaṃ maññissāmā’ti. Evañhi vo, bhikkhave,

sikkhitabbanti.

Therefore, bhikkhus, you should

train thus: ‘We will listen to the utterance of such discourses which

are words of the Tathāgata, profound, profound in meaning, leading

beyond the world, (consistently) connected with emptiness, we will lend

ear, we will apply our mind on knowledge, we will consider those

teachings as to be taken up and mastered.’ This is how, bhikkhus, you

should train yourselves.

Listening to (and Learning) the Dhamma

Listening to (and Learning) the Dhamma

– Dhamma Teaching by the Buddha

with commentaries by Ven. K. Sri Dhammananda and Thanissaro Bhikkhu

The Buddha said …

‘Staying at Savatthi. “Monks, there once was a time when the Dasarahas

had a large drum called ‘Summoner.’ Whenever Summoner was split, the

Dasarahas inserted another peg in it, until the time came when

Summoner’s original wooden body had disappeared and only a

conglomeration of pegs remained.

“In the same way, in the course of the future there will be monks who

won’t listen when discourses that are words of the Tathagata — deep,

deep in their meaning, transcendent, connected with emptiness — are

being recited. They won’t lend ear, won’t set their hearts on knowing

them, won’t regard these teachings as worth grasping or mastering. But

they will listen when discourses that are literary works — the works of

poets, elegant in sound, elegant in rhetoric, the work of outsiders,

words of disciples — are recited. They will lend ear and set their

hearts on knowing them. They will regard these teachings as worth

grasping & mastering.

“In this way the disappearance of the discourses that are words of

the Tathagata — deep, deep in their meaning, transcendent, connected

with emptiness — will come about.

“Thus you should train yourselves: ‘We will listen when discourses

that are words of the Tathagata — deep, deep in their meaning,

transcendent, connected with emptiness — are being recited. We will lend

ear, will set our hearts on knowing them, will regard these teachings

as worth grasping & mastering.’ That’s how you should train

yourselves.” ‘

– Āṇi Sutta : The Peg SN 20.7

– Source : www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/sn/sn20/sn20.007.than.html

Āṇi Sutta : The Peg SN 20.7

—

‘Message for All’

by Ven. K. Sri Dhammananda

‘.. The Buddha taught man that the greatest of conquests was not the

subjugation of others but of the self. He taught in the Dhammapada, ..’

‘Though one may conquer a thousand times

a thousand men in battle,

yet he indeed is the noblest victor

who conquers himself.’

– Dhammapada Verse 103

Read ‘Message for All’

in full here … www.budsas.org/ebud/whatbudbeliev/28.htm

—

Tipitaka is the collection of the teachings of the Buddha over 45

years in the Pāli language, and it consists of Sutta – conventional

teaching, Vinaya – disciplinary code, and Abhidhamma – moral psychology.

Read ‘Tri-Pitaka (or Tipitaka)’

by Ven. K. Sri Dhammananda

in full here … www.budsas.org/ebud/whatbudbeliev/62.htm

—

Dhamma Sharing (Video)

‘Dhamma Study – Recognizing the Dhamma’

by Thanissaro Bhikkhu

p1- https://youtu.be/DcEQjBsjzMM

p2- https://youtu.be/W8yuYxc9vIs

p3- https://youtu.be/VjUel0exuZ8

p4- https://youtu.be/xkP0A1_byeA

p5- https://youtu.be/ujs_RGttV0s

p6- https://youtu.be/EkVGm9FKSq0

Read ‘Recognizing the Dhamma : A Study Guide’

by Thanissaro Bhikkhu, here …

www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/study/recognizing.html

—

The eight principles for recognizing what qualifies

as Dhamma and Vinaya,

as taught in the Gotami Sutta AN 8.53.

‘I have heard that at one time the Blessed One was staying at Vesali, in the Peaked Roof Hall in the Great Forest.

Then Mahapajapati Gotami went to the Blessed One and, on arrival,

having bowed down to him, stood to one side. As she was standing there

she said to him: “It would be good, lord, if the Blessed One would teach

me the Dhamma in brief such that, having heard the Dhamma from the

Blessed One, I might dwell alone, secluded, heedful, ardent, &

resolute.”

“Gotami, the qualities of which you may know, ‘These qualities lead

to passion, not to dispassion; to being fettered, not to being

unfettered; to accumulating, not to shedding; to self-aggrandizement,

not to modesty; to discontent, not to contentment; to entanglement, not

to seclusion; to laziness, not to aroused persistence; to being

burdensome, not to being unburdensome’: You may categorically hold,

‘This is not the Dhamma, this is not the Vinaya, this is not the

Teacher’s instruction.’

“As for the qualities of which you may know, ‘These qualities lead to

dispassion, not to passion; to being unfettered, not to being fettered;

to shedding, not to accumulating; to modesty, not to

self-aggrandizement; to contentment, not to discontent; to seclusion,

not to entanglement; to aroused persistence, not to laziness; to being

unburdensome, not to being burdensome’: You may categorically hold,

‘This is the Dhamma, this is the Vinaya, this is the Teacher’s

instruction.’”

That is what the Blessed One said. Gratified, Mahapajapati Gotami delighted at his words.’

– Gotami Sutta : To Gotami AN 8.53

– Source : www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/an/an08/an08.053.than.html

– Posted by CFFong

chief Mayawati makes ugly personal attack at PM Modi, says ‘wives of

BJP leaders are wary he’ll make their husbands leave them’

Friends

https://indianexpress.com/…/farm-bills-anti-farmer…/

Farm bills anti-farmer, will help rich: Mayawati and Akhilesh

The

Lok Sabha on Thursday passed The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce

(Promotion and Facilitation) Bill, 2020 and The Farmers (Empowerment and

Protection) Agreement of Price Assurance and Farm Services Bill, 2020

Bahujan

Samaj Party (BSP) chief Mayawati and Samajwadi Party chief Akhilesh

Yadav on Friday slammed the BJP government at the Centre for the farm

Bills, calling them “anti-farmer” and “pro-rich”.

The Lok Sabha on

Thursday passed The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and

Facilitation) Bill, 2020 and The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection)

Agreement of Price Assurance and Farm Services Bill, 2020.

Questioning

the manner in which the Bills were passed in the Lok Sabha, Mayawati

said, “Sansad mein kisanon se jure do Bill, unki sabhi shankaon ko door

kiye bina hi, kal paas kar diye gaye hain. Ush se BSP katai sehmat nahi

hai. (Two Bills related to farmers were passed in Parliament yesterday

without clearing doubts related to them. The BSP does not approve of it

at all.” She further said, “What does farmer of the entire country want?

It would be better if the Central government pays attention in this

direction.”

Samajwadi Party chief Akhilesh Yadav termed the two farm

Bills “pro-rich and anti-farming”, and said that once they come into

effect, they would reduce the farmers as mere labourers on their own

fields and would take away their right of getting appropriate price for

their crop.

“BJP sarkar kheti ko ameeron ke hathon girwi rakhne ke

liye shoshankari vidheyak layi hai.” (The BJP government has brought

these Bills, which would mortgage the farms in the hands of rich and

will exploit them).”

Akhilesh further said that these Bills were

being passed “to end the protection given to the farmers and slowly

finish the mandis where farmers sell their crop at minimum support price

(MSP). He said that in the future, the minimum support price to farmers

would be done away with and farmers will just work as labourers in

their own fields (“Woh apni hi jameen par majdoor ban jayenge”).

In Parliament too, members of the Samajwadi Party and Bahujan Samaj Party have joined the Opposition ranks to oppose the Bills.

Farm bills anti-farmer, will help rich: Mayawati and Akhilesh

indianexpress.com

Farm bills anti-farmer, will help rich: Mayawati and Akhilesh

https://www.indiatoday.in/…/war-of-words-between-pm…

War of words between PM Modi and Mayawati

indiatoday.in

War of words between PM Modi and Mayawati

Mayawati claimed that women legislators in the Bharatiya Janata Pa

Instrumental music.

Instrumental music. In Pure Land

In Pure Land