Right Action

http://sophanse.blogspot.com/2006_03_24_sophanse_archive.html

Right Action (samma kammanta)

Right action means refraining from unwholesome deeds that occur with the body as their natural means of expression. The pivotal element in this path factor is the mental factor of abstinence, but because this abstinence applies to actions performed through the body, it is called “right action.” The Buddha mentions three components of right action: abstaining from taking life, abstaining from taking what is not given, and abstaining from sexual misconduct. These we will briefly discuss in order.

(1) Abstaining from the taking of life (panatipata veramani)

Herein someone avoids the taking of life and abstains from it. Without stick or sword, conscientious, full of sympathy, he is desirous of the welfare of all sentient beings.28

“Abstaining from taking life” has a wider application than simply refraining from killing other human beings. The precept enjoins abstaining from killing any sentient being. A “sentient being” (pani, satta) is a living being endowed with mind or consciousness; for practical purposes, this means human beings, animals, and insects. Plants are not considered to be sentient beings; though they exhibit some degree of sensitivity, they lack full-fledged consciousness, the defining attribute of a sentient being.

The “taking of life” that is to be avoided is intentional killing, the deliberate destruction of life of a being endowed with consciousness. The principle is grounded in the consideration that all beings love life and fear death, that all seek happiness and are averse to pain. The essential determinant of transgression is the volition to kill, issuing in an action that deprives a being of life. Suicide is also generally regarded as a violation, but not accidental killing as the intention to destroy life is absent. The abstinence may be taken to apply to two kinds of action, the primary and the secondary. The primary is the actual destruction of life; the secondary is deliberately harming or torturing another being without killing it.

While the Buddha’s statement on non-injury is quite simple and straightforward, later commentaries give a detailed analysis of the principle. A treatise from Thailand, written by an erudite Thai patriarch, collates a mass of earlier material into an especially thorough treatment, which we shall briefly summarize here.29 The treatise points out that the taking of life may have varying degrees of moral weight entailing different consequences. The three primary variables governing moral weight are the object, the motive, and the effort. With regard to the object there is a difference in seriousness between killing a human being and killing an animal, the former being kammically heavier since man has a more highly developed moral sense and greater spiritual potential than animals. Among human beings, the degree of kammic weight depends on the qualities of the person killed and his relation to the killer; thus killing a person of superior spiritual qualities or a personal benefactor, such as a parent or a teacher, is an especially grave act.

The motive for killing also influences moral weight. Acts of killing can be driven by greed, hatred, or delusion. Of the three, killing motivated by hatred is the most serious, and the weight increases to the degree that the killing is premeditated. The force of effort involved also contributes, the unwholesome kamma being proportional to the force and the strength of the defilements.

The positive counterpart to abstaining from taking life, as the Buddha indicates, is the development of kindness and compassion for other beings. The disciple not only avoids destroying life; he dwells with a heart full of sympathy, desiring the welfare of all beings. The commitment to non-injury and concern for the welfare of others represent the practical application of the second path factor, right intention, in the form of good will and harmlessness.

(2) Abstaining from taking what is not given (adinnadana veramani)

He avoids taking what is not given and abstains from it; what another person possesses of goods and chattel in the village or in the wood, that he does not take away with thievish intent.30

“Taking what is not given” means appropriating the rightful belongings of others with thievish intent. If one takes something that has no owner, such as unclaimed stones, wood, or even gems extracted from the earth, the act does not count as a violation even though these objects have not been given. But also implied as a transgression, though not expressly stated, is withholding from others what should rightfully be given to them.

Commentaries mention a number of ways in which “taking what is not given” can be committed. Some of the most common may be enumerated:

(1) stealing: taking the belongings of others secretly, as in housebreaking, pickpocketing, etc.;

(2) robbery: taking what belongs to others openly by force or threats;

(3) snatching: suddenly pulling away another’s possession before he has time to resist;

(4) fraudulence: gaining possession of another’s belongings by falsely claiming them as one’s own;

(5) deceitfulness: using false weights and measures to cheat customers.31

The degree of moral weight that attaches to the action is determined by three factors: the value of the object taken; the qualities of the victim of the theft; and the subjective state of the thief. Regarding the first, moral weight is directly proportional to the value of the object. Regarding the second, the weight varies according to the moral qualities of the deprived individual. Regarding the third, acts of theft may be motivated either by greed or hatred. While greed is the most common cause, hatred may also be responsible as when one person deprives another of his belongings not so much because he wants them for himself as because he wants to harm the latter. Between the two, acts motivated by hatred are kammically heavier than acts motivated by sheer greed.

The positive counterpart to abstaining from stealing is honesty, which implies respect for the belongings of others and for their right to use their belongings as they wish. Another related virtue is contentment, being satisfied with what one has without being inclined to increase one’s wealth by unscrupulous means. The most eminent opposite virtue is generosity, giving away one’s own wealth and possessions in order to benefit others.

(3) Abstaining from sexual misconduct (kamesu miccha-cara veramani)

He avoids sexual misconduct and abstains from it. He has no intercourse with such persons as are still under the protection of father, mother, brother, sister or relatives, nor with married women, nor with female convicts, nor lastly, with betrothed girls.32

The guiding purposes of this precept, from the ethical standpoint, are to protect marital relations from outside disruption and to promote trust and fidelity within the marital union. From the spiritual standpoint it helps curb the expansive tendency of sexual desire and thus is a step in the direction of renunciation, which reaches its consummation in the observance of celibacy (brahmacariya) binding on monks and nuns. But for laypeople the precept enjoins abstaining from sexual relations with an illicit partner. The primary transgression is entering into full sexual union, but all other sexual involvements of a less complete kind may be considered secondary infringements.

The main question raised by the precept concerns who is to count as an illicit partner. The Buddha’s statement defines the illicit partner from the perspective of the man, but later treatises elaborate the matter for both sexes.33

For a man, three kinds of women are considered illicit partners:

(1) A woman who is married to another man. This includes, besides a woman already married to a man, a woman who is not his legal wife but is generally recognized as his consort, who lives with him or is kept by him or is in some way acknowledged as his partner. All these women are illicit partners for men other than their own husbands. This class would also include a woman engaged to another man. But a widow or divorced woman is not out of bounds, provided she is not excluded for other reasons.

(2) A woman still under protection. This is a girl or woman who is under the protection of her mother, father, relatives, or others rightfully entitled to be her guardians. This provision rules out elopements or secret marriages contrary to the wishes of the protecting party.

(3) A woman prohibited by convention. This includes close female relatives forbidden as partners by social tradition, nuns and other women under a vow of celibacy, and those prohibited as partners by the law of the land.

From the standpoint of a woman, two kinds of men are considered illicit partners:

(1) For a married woman any man other than her husband is out of bounds. Thus a married woman violates the precept if she breaks her vow of fidelity to her husband. But a widow or divorcee is free to remarry.

(2) For any woman any man forbidden by convention, such as close relatives and those under a vow of celibacy, is an illicit partner.

Besides these, any case of forced, violent, or coercive sexual union constitutes a transgression. But in such a case the violation falls only on the offender, not on the one compelled to submit.

The positive virtue corresponding to the abstinence is, for laypeople, marital fidelity. Husband and wife should each be faithful and devoted to the other, content with the relationship, and should not risk a breakup to the union by seeking outside partners. The principle does not, however, confine sexual relations to the marital union. It is flexible enough to allow for variations depending on social convention. The essential purpose, as was said, is to prevent sexual relations which are hurtful to others. When mature independent people, though unmarried, enter into a sexual relationship through free consent, so long as no other person is intentionally harmed, no breach of the training factor is involved.

Ordained monks and nuns, including men and women who have undertaken the eight or ten precepts, are obliged to observe celibacy. They must abstain not only from sexual misconduct, but from all sexual involvements, at least during the period of their vows. The holy life at its highest aims at complete purity in thought, word, and deed, and this requires turning back the tide of sexual desire.

Stream-enterer

I spoke of stream entry yesterday. Basically it’s the first seeming hurdle (seeming as I, as many do, get stuck in terms of thinking of cause-and-effect linear stepwise) on the seeming path to Awakenment. In other words, there is no path to what you already are.

Buddha: “What do you think, Subhuti? Does a Stream-Enterer think, ‘I have attained the fruit of stream-entry.’?”

Subhuti replied, “No, World-Honored One. Why? Stream-Enterer means to enter the stream, but in fact there is no stream to enter. One does not enter a stream that is form, nor a stream that is sound, smell, taste, touch, or object of mind. That is what we mean when we say entering a stream.” - The Diamond Sutra

Yep, and now there’s no turning back either…

According to Buddhism, a stream-enterer “gains its name from the fact that a person who has attained this level has entered the “stream” flowing inevitably to nibbana. He/she is guaranteed to achieve full awakening within seven lifetimes at most, and in the interim will not be reborn in any of the lower realms.”

David Hawkins’ new book also mentions that a level of consciousness of “unconditional love”, or 540 on (the, again, seemingly linear) scale 1 to 1000 as achievable by anyone and everyone that commits to it. He’s a bit more skeptical of full enlightenment in one lifetime…but what if you’ve lost track of how many lifetimes you’ve been at this? ![]()

In accounts of the life of the Buddha, there are many examples of people immediately understanding his teaching and breaking the first three ‘fetters’ that hinder people from seeing Reality. These fetters are: having a fixed view of oneself; doubt; and being attached to rites and rituals as ends in themselves. Such people become ‘stream entrants’ — because they have entered the stream that draws them irresistibly towards Enlightenment.

Over the centuries there has been a tendency to emphasise the difficulty of making such a breakthrough [this blog will emphasize the ease!], and some Buddhist schools teach that it may take many lifetimes, or even that it’s no longer possible. Sangharakshita has a different understanding. He suggests that all sincere, committed and effective Dharma practitioners, who have supportive conditions and enough time, could reasonably expect to make substantial progress and even gain Stream Entry in this lifetime. - Friends of the Western Buddhist Order

Once-returner

The Magnification off a pre-Streamwinner being incalculable and immeasurable, what can be said of that off a Once-Returner?

abbreviation Ariya, Sanskrit Arya-pudgala, in Theravada Buddhism, a person who has attained one of the four levels of holiness. A first type of holy person, called a sotapanna-puggala (“stream-winner”), is one who will attain Nirvana (the supreme goal of Buddhist thought and practice) after no more than seven rebirths. Another type of holy person is termed a sakadagamin (“once-returner”), or one who is destined to be reborn

Non-returner

-

-

The third of the four stages of Hinayana awakenment. The fourth and highest stage is the stage of arhat. The stage of the non-returner is the stage in which one has eliminated the desires and delusions of the world of desire. At this stage, one will not be reborn in the world of desire; hence the term “non-returner.” Instead one will be reborn in the world of form or the world of formlessness. The anagamin means not coming, not arriving, or not subject to returning.

Arahant

State of an Arahant after passing away

| What is the state of the Arahant after death? Is it a state of annihilation, of non existence, or a state of eternal existence in some other form. The Buddha rejects both these alternatives, declaring that this question is inapplicable.

The question, “What is the state of the Arahant after death?” arises because of the subtle clinging to the idea that an Arahant has a self. But since the Arahant has no self, he does not enter into any state of eternal existence in some heavenly world or as a universal self in some impersonalized form. Also final Nibbana is not a state of annihilation, since there is no self to be annihilated or extinguished. What we call the Arahant is a dependently arisen process of becoming, and the attainment of final Nibbana is cessation of this process of becoming. To try to speak about what lies beyond the ending of this process is to venture outside the boundaries of conceptualization, outside the boundaries of language. The Buddha says;

So from this we see that concepts cannot conceive the ‘inconceivable’ and the mind cannot measure the ‘immeasurable’. The Buddha illustrates this with the example of a fire. Suppose there is a fire, burning in dependence on fuel, the sticks and logs. Now if the fire does not get any further fuel, when it uses up the old fuel, then it goes out. Suppose we ask, when the fire goes out; where did it go? Did it go to the North? To the South? To the East? To the West? The answer to this is that none of these questions apply. All of these are inapplicable. The fire has simply gone out. |

Question and Answers

Answer to Question No 10 of Questionnaire 8

10. Describe all the historic events, one after another, following the defeat of Maara, between a) the first watch between

Siddhattha - Life as a Prince and Renunciation - with meditation teachers - Practice of severe austerities - his meditation before Awakenment - the Three Knowledges - inspired verses after Awakenment- who to teach? The five ascetics - Añña Kondaññā, the first Arahant.

Prince Siddhattha, heir to the throne of the Sākiyan kingdom, saw, in spite of his father’s endeavours, old age, disease and death; and also a religious wanderer in yellow robes who was calm and peaceful. When he had seen these things, withheld from him until his early manhood, he was shocked by the sight of the first three realising that he also must suffer them, but he was inspired by the fourth and understood that this was the way to go beyond the troubles, and sufferings of existence. Though his beautiful wife, Yasodharā presented him with a son who was called Rāhula, he was no longer attracted to worldly life. His mind was set upon renunciation of the sense pleasures and uprooting the desires, which underlay them.

So at night he left behind his luxurious life and going off with a single retainer, reached the Sākiyan frontiers. There he dismounted from his horse, took off his princely ornaments and cut off his hair and beard with his sword. Then he changed into yellowish-brown patched robes and so transformed himself into a Bhikkhu or wandering monk. The horse and valuables he told his retainer to take back with the news that he had renounced pleasures and gone forth from home to homelessness.

At first he went to various meditation teachers but he was not satisfied with their teachings when he became aware that they could not show him the way out of all suffering. Their attainments, which he equalled, were like temporary halts on a long journey, they were not its end. They led only to birth in some heaven where life, however long, was nevertheless impermanent. So he decided to find his own way by bodily mortification. This he practised for six years in every conceivable way, going to extremes, which other ascetics would be fearful to try. Finally, on the edge of life and death, he perceived the futility of bodily torment and remembered from boyhood a meditation experience of great peace and joy. Thinking that this was the way, he gave up troubling his body, and took food again to restore his strength. So in his life he had known two extremes, one of luxury and pleasure when a prince, the second of fearful austerity, but both he advised his first Bhikkhu disciples, should be avoided.[1]

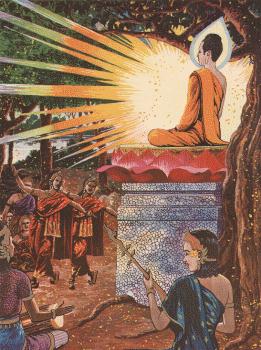

Having restored his strength, he sat down to meditate under a great pipal tree, later known as the Bodhi (Enlightenment) Tree. His mind passed quickly into four states of deep meditation called jhāna. In these, the mind is perfectly one-pointed and there is no disturbance or distraction. No words, no thoughts and no pictures, only steady and brilliant mindfulness. Some mental application and inspection is present at first along with physical rapture and mental bliss. But these factors disappear in the process of refinement until in the fourth jhāna only equanimity, mindfulness and great purity are left. On the bases of these profound meditation states certain knowledge arose in his mind.

These knowledge, which when they appear to a meditator are quite different from things which are learnt or thought about, were described by him in various ways. It is as though a person standing at various points on a track, which is roughly circular, should describe different views of the same landscape; in the same way the Buddha described his Bodhi or awakening experience. Some parts of this experience would be of little or no use to others in their training so these facts he did not teach. What he did teach was about dukkha or suffering, how it arises and how to get beyond it. One of the most frequent views into this ‘landscape of Awakenment’ is the Three Knowledges: of past lives, of kamma and its results, and of the destruction of the mental pollution.

The wisdom of knowing his own past lives, hundreds of thousands of them, an infinite number of them, having no beginning - all in detail with his names and occupations, the human, super-human and sub-human ones, showed him the futility of searching for sense-pleasures again and again. He saw as well that the wheel of birth and death kept in motion by desires for pleasure and existence would go on spinning for ever producing more and more of existence bound up with unsatisfactory conditions. Contemplating this stream of lives he passed the first watch of the night under the Bodhi Tree.

The wisdom pertaining to kamma[2] and its results means that he surveyed with the divine interior eye all sorts of beings, human and otherwise and saw how their past kammas gave rise to present results and how their present kammas will fruit in future results. Wholesome kammas, developing one’s mind and leading to the happiness of others, fruit for their doer as happiness of body and mind, while unwholesome kammas which lead to deterioration in one’s own mind and suffering for others, result for the doer of them in mental and physical suffering. The second watch of the night passed contemplating this wisdom.

In the last watch he saw how the pollution, the deepest layer of defilement and distortion, arise and pass away conditionally. With craving and ignorance present, the whole mass of sufferings, gross and subtle, physical and mental - all that is called dukkha, come into existence; but when they are abandoned then this burden of dukkha, which weighs down all beings and causes them to drag through myriad lives, is cut off and can never arise again. This is called the knowledge of the destruction of the pollutions: desires and pleasures, existence and ignorance, so that craving connected with these things is extinct.

When he penetrated to this profound truth, the arising and passing away conditionally of all experience and thus of all dukkha, he was the Buddha, Enlightened, Awakened. Dukkha he had known thoroughly in all its most subtle forms and he discerned the causes for it’s arising - principally - craving. Then he experienced its cessation when its roots of craving had been abandoned, this cessation of dukkha also called Nibbāna, the Bliss Supreme. And he investigated and developed the Way leading to the cessation of dukkha, which is called the Noble Eightfold Path. This Path is divided into three parts: of wisdom - Right View and Right Thought; of moral conduct - Right Speech, Right Action and Right Livelihood; of mind development - Right Effort, Right Mindfulness and Right Collectedness. It has been described many times in detail.[3]

We are told that to the Buddha experiencing the bliss supreme of Enlightenment the following two verses occurred:

-

„Through many births in the wandering-on

-

I ran seeking but finding not

-

the maker of this house -

-

dukkha is birth again, again.

-

-

O house maker, you are seen!

-

You shall not make a house again;

-

all your beams are broken up,

-

rafters of the ridge destroyed:

-

the mind gone to the Unconditioned,

-

to craving’s destruction it has come“.

-

(Dhammapada, verses 153-154)

Now that he had come to the end of craving and desire, a thing, so difficult to do, and after reviewing his freedom from the round of birth and death, he concluded that no one in the world would understand this teaching. Men are blinded by their desires, he thought and his mind inclined towards not teaching the Dhamma. Then with the divine eye he saw that there were a few beings „with little dust in their eyes“ and who would understand. First he thought of the two teachers he had gone to and then left dissatisfied but both had died and been reborn in the planes of the formless deities having immense life spans. They would not be able to understand about ‘arising and passing away’. Then he considered the whereabouts of the five ascetics who had served him while he practised severe bodily austerities. The knowledge came to him that they were near Benares, in the Deer-sanctuary at Isipatana; so he walked there by slow stages. So he began the life of a travelling Bhikkhu, the hard life that he was to lead out of compassion for suffering beings for the next forty-five years.

When the Buddha taught these five ascetics he addressed them as ‘Bhikkhus’. This is the word now used only for Buddhist monks but at that time applied to other religious wanderers. Literally, it means ‘one who begs’ (though Bhikkhus are not allowed to beg from people, they accept silently whatever is given. See Chapter VI). At the end of the Buddha’s first discourse[4], Kondaññā[5] the leader of those Bhikkhus, penetrated to the truth of the Dhamma. Knowing that he had experienced a moment of Enlightenment - Stream-winning as it is called, the Buddha was inspired to say, „Kondaññā truly knows indeed Kondaññā truly knows!“ Thus he came to be known as Añña-Kondaññā - Kondaññā who knows as it really is.

MAHA BODHI SOCIETY-Questionnaire No 9 and Answers of First Year Diploma Course conducted by Mahabodhi Academy for Pali and Buddhist Studies

1.

What did Buddha do after his Supreme Awakenment?He uttered a Paean of Joy (Udana)

- Thro’many a birth in Samsara wandered I,

- Seeking, but not finding, the builderr of this house.

- Sorrowful is repeated birth.

- O house-builder ! Thou art seen.

- All thy rafters are broken thy ridgeppole is shattered.

- The mind attains the unconditioned.< ?XML:NAMESPACE PREFIX = OO />

- Achieved is the end of craving.*

*Udana in Pali :

Anekajàti samsàram sandhavissam anibbisam Gahàkarakam bavesanto dukkhà jàti punapunam Gahakàraka dittho’ si puna geham na kàhasi Sabbà te phàsuka bhagga gahakùtam visamkhitam Vesamkhàragatam cittam tanhanam khayamajjhagà.

The Buddha fasted for seven weeks.

The Awakened One was then faced with a choice. He could enter nibbana: literally, the cessation, of mental turnings, vritti; the undisturbed condition of supreme consciousness. Or, renouncing personal deliverance for the moment, he could preach the law. Mara urged one course, Brahma the other, and it was to the great god’s entreaties on behalf of all created things the Buddha yielded. He began to travel and teach, founding a monastic order as well as preparing the framework for the Buddhist era of Indian civilization. One day a little child wanted to make him an offering, but had no worldly possessions. Innocently the boy presented for blessing a pile of dust, which the Buddha accepted with a smile. This child is reputed to have been reborn as King Asoka, who reigned from 272 to 232 BC. Not only did this monarch establish throughout his realm countless monasteries and have constructed 80,000 stupas, or reliquary shrines, but his Buddhist missionaries were dispatched even to Syria and Egypt.

Tibetan carving of the Buddha

2. What happened during the first week?

Throughout the first week He sat under the Bodhi Tree enjoying the Bliss of Freedom.

He meditated on the “Wheel of Life”.

3. What happened during the second week?

He stood at a certain distance gazing at the Bodhi Tree with motionless eyes.

*On the spot where the Buddha stood a Cetiya has been erected by King Dharmasoka. This was named Animisalocana Cetiya and is still to be seen.

Why did He do so ?

He did so as a mark of gratitude to the tree.

In what way was the Bodhi Tree helpful to the Buddha ?

The Tree only gave Him shelter during His struggle for Buddhahood.

What was the first lesson the Buddha taught to the world ?

The great lesson of Gratitude.

4. What happened during the third week?

He walked up and down a jewelled promenade (Ratana Camkamana).

5. What happened during the fourth week?

Sitting in a chamber, He meditated on the Higher Dhamma (Abhidhamma).

6. What happened during the fifth week?

He sat under the Ajapala Banyan tree.

Who came to tempt him at this time ?

Thee daughters of Mara came to tempt Him.

Mention their names.

Tanha, Arati and Raga.

Could they be passioned ?

They cannot be passioned because this happened after the Awakenment.

7. What happened during the sixth week?

Under the Mucalinda tree.

What happened during this week ?

It rained heavily and a serpent king sheltered Him.

8. What happened during the seventh week?

What happened on the 50th day ?

Two merchants named Tapassu and Bhallika offered Him dried flour and honey.

What did they do after the Dana ?

They sought refuge in the Buddha and The Dhamma.

How did they seek refuge ?

By reciting Buddham saranam gacchami, Dhammam saranam gacchami.

Why didn’t they seek refuge in the Sangha ?

Because there was no Sangha then.

Did they want anything from the Buddha ?

Yes, they wanted something to worship.

What did the Buddha give them ?

The Buddha touched His head and gave them some hair relic.

Where are they enshrined now ?

They are enshrined in the Shve Dagon Pagoda in Rangoon.

Who were the first Upasakas of the Buddha ?

Tapassu and Bhallika were the first Upasakas.

Who is an Upasaka ?

An Upasaka is a lay follower of the Buddha

9. Write down the text of Paticca Samppada both in Pali and English in forward and forward orders.

Kindly visit:

http://www.buddhanet.net/audio-chant.htm for Paticca Samppada both in Pali and English

10. Write an essay of twelve factors of dependent origination. What does the dependent origination portray?

Paticca-Samuppada: Dependent Origination

It is rather with some hesitation that I dare to speak to you on that profoundest of all Buddhist doctrines, paticca-samuppada, “dependent origination,” that is to say, the conditional arising of all those mental and physical phenomena generally summed up by the conventional names “living being,” or “individual,” or “person.” Thus, being well aware of the great difficulty of speaking on this most intricate subject before an audience perhaps only little acquainted with Buddhist philosophy, I shall try my utmost to avoid, as far as possible, all the highly technical or confusing details. I shall use very plain and simple language, so that any one of you may be able to follow my explanations. At the same time I shall not lose sight of the real goal and purpose for which the Buddha taught this doctrine to the world. Thus I would beg you to listen carefully and give my words full and undivided attention. And I further beg you to try to retain in mind those very few technical terms in Pali and English which in the course of my talk I shall be repeatedly using.

You may not be aware that, up to this day, the real significance and purpose of paticca-samuppada are practically unknown to Western scholars. By this, however, I do not mean to say that nobody in the West has ever written or spoken on this doctrine. No, quite the contrary is the case. For there is no other Buddhist doctrine about which Western scholars, and would-be scholars, have written and discussed so much — but understood so little — as just this doctrine of paticca-samuppada. If you wish to get a fair idea of those mostly absurd and immature speculations and fanciful interpretations, often based on mere imagination, you may read the Appendix to my Guide through the Abhidhamma Pitaka.1 It seems that scarcely one of those Western authors and lecturers has ever put to himself the question, for what earthly reason the Buddha ever should have thought it necessary to teach such a doctrine. It was surely not for the sake of mental gymnastics and dialectics. No, quite to the contrary! For paticca-samuppada shows the causes and conditions of all the suffering in the world; and how, through the removal of these conditions, suffering may rise no more in the future. P.S. in fact shows that our present existence, with all its woe and suffering, is conditioned, or more exactly said caused, by the life-affirming volitions or kamma in a former life, and that again our future life depends on the present life-affirming volitions or kamma; and that without these life-affirming volitions, no more future rebirth will take place; and that thereby deliverance will have been found from the round of rebirths, from the restless cycle of Samsara. And this is the final goal and purpose of the Buddha’s message, namely, deliverance from rebirth and suffering.

I think that after what you have heard just now, it will not be necessary to tell you that P.S. is not intended, as various scholars in the West have imagined, as an explanation of the primary beginning of all things; and that its first link, avijja or ignorance, is not to be considered the causeless first principle out of which, in the course of time, all physical and conscious life has evolved. P.S. simply teaches the conditionality, or dependent nature, of all the manifold mental and physical phenomena of existence; of everything that happens, be it in the realm of the physical or the mental. P.S. shows that the sum of mental and physical phenomena known by the conventional name “person” or “individual” is not at all the mere play of blind chance; but that each phenomenon in this process of existence is entirely dependent upon other phenomena as conditions; and that therefore with the removal of those phenomena that form the conditions for rebirth and suffering, rebirth and therewith all suffering will necessarily cease and come to an end. And this, as already stated, is the vital point and goal of the Buddha’s teaching: deliverance from the cycle of rebirth with all its woe and suffering. Thus P.S. serves in the elucidation of the second and third noble truths about the origin and extinction of suffering, by explaining these two truths from their very foundations upwards, and giving them a fixed philosophical form.2

In the discourses of the Buddha, P.S. is usually expounded by way of twelve links arranged in eleven propositions. They are as follows:

- Avijjapaccaya sankhara: “Through ignorance the rebirth-producing volitions, or kamma-formations, are conditioned.”

- Sankhara-paccaya viññanam:“Through the kamma-formations (in the past life, the present) consciousness is conditioned.”

- Viññana-paccaya nama-rupam:“Through consciousness the mental and physical phenomena (which make up our so-called individual existence) are conditioned.”

- Nama-rupa-paccaya salayatanam:“Through the mental and physical phenomena the six bases (of mental life, i.e. the five physical sense-organs and consciousness as the sixth) are conditioned.”

- Salayatana-paccaya phasso:“Through the six bases the (sensory and mental) impression is conditioned.”

- Phassa-paccaya vedana: “Through (the sensory or mental) impression feeling is conditioned.”

- Vedana-paccaya tanha: “Through feeling craving is conditioned.”

- Tanha-paccaya upadanam:“Through craving clinging is conditioned.”

- Upadana-paccaya bhavo:“Through clinging the process of becoming (consisting of the active and the passive life-process, that is to say, the rebirth-producing kammic process, and as its result, the rebirth-process) is conditioned.”

- Bhava-paccaya jati:“Through the (rebirth-producing kammic) process of becoming rebirth is conditioned.”

- Jati-paccaya jaramaranam, etc.: “Through rebirth, decay and death, sorrow, lamentation, pain, grief and despair are conditioned. Thus arises this whole mass of suffering (in the future).”

This is in brief the whole P.S. or dependent origination. Now let us carefully examine the eleven propositions one by one.

1

Our first proposition was: Avijja-paccaya sankhara: “Through ignorance the kamma-formations are conditioned.”

Avijja,3 also called moha, is delusion, infatuation: regarding fleeting things as permanent, miserable things as enjoyment, and egoless things as a self or ego. Avijja is ignorance, not understanding that all our existence is merely an ever-changing process of mental and physical phenomena; it is not understanding that these phenomena, in the ultimate sense, do not form any real permanent entity, or person, or ego; and that there does not exist any permanent entity in, or behind, these fleeting physical and mental phenomena; that therefore what we call “I,” or “you,” or “he,” or “person,” or “Buddha,” etc., does not, in the ultimate sense (paramattha), possess any reality apart from these ever-changing physical and mental phenomena of existence. Avijja, or moha, is the primary root-condition underlying all moral defilement and depravity. In avijja are rooted all the greed, hatred, conceit, envy and misery in the world. And the overcoming and extinction of avijja, and therewith of all evil and misery, is the final aim of the Buddha’s teaching, the ideal for any true Buddhist. And it is for these reasons that avijja is mentioned first in the formula of P.S.

By sankhara, lit. “formations,” are here meant the rebirth-producing, kammically unwholesome or wholesome volitions (cetana), or volitional activities. Let us therefore remember sankhara as kamma-formations, or simply as kamma.4

Now, all such evil volitions manifested by body, speech or mind, as above alluded to, are called akusala or unwholesome kamma-formations, as they bring unhappy results, here and in the after-life. Kusala or wholesome kamma-formations, however, are such volitions, or cetana, as will bring happy and pleasant results, here and in the after-life. But even these wholesome kamma-formations are still conditioned and influenced by avijja, as otherwise they would not produce future rebirth. And there is only one individual who no longer performs any wholesome or unwholesome kamma-formation, any life-affirming kamma. It is the Arahant, the holy and fully enlightened disciple of the Buddha. For through deep insight into the true nature of this empty and evanescent process of existence, he has become utterly detached from life; and he is forever freed from ignorance together with all its evil consequences, freed from any further rebirth.

Avijja is to all unwholesome kamma-formations, or volitional activities, an indispensable condition by way of its presence and simultaneous arising. For example, whenever an evil manifestation of will, an evil kamma-formation, arises, at that very same moment its arising is conditioned through the simultaneous arising and presence of avijja. Without the co-arising of avijja, there is no evil kamma-formation. When, for example, an infatuated man, filled with greed or anger, commits various evil deeds by body, speech or mind, at that time these evil kamma-formations are all entirely conditioned through the co-arising and presence of avijja, or ignorance. Thus if there is no avijja, there are no evil kamma-formations. Therefore it is said that avijja is to its associated kamma-formations a condition by way of co-nascence, or simultaneous arising (sahajata). Further, as there is no evil kamma-formation without the presence of avijja, and no avijja without the presence of evil kamma-formations, therefore both are at any time, and under all circumstances, also mutual conditions to each other (aññam-añña-paccaya); and thus avijja and the evil kamma-formations are inseparable. In so far as avijja is an ever-present root of all evil kamma-formations, we say that avijja is to the unwholesome kamma-formations an indispensable condition by way of root (hetu).

But there is still another and entirely different way in which avijja may be a condition to unwholesome kamma-formations, that is, as inducement. For example, if a man, being filled with greed or anger, is induced by his infatuation and delusive thoughts to commit various crimes, such as murder, theft, adultery, etc., in that case avijja is the direct inducement and driving power for the subsequent arising of all those bad manifestations of will, i.e. of all those unwholesome kamma-formations. In other words, those bad unwholesome kamma-formations are conditioned by a preceding state of avijja as a direct inducement (pakat’ upanissaya-paccaya).

There is still another way in which avijja may become an inducement to unwholesome kamma-formations, namely, as object of thinking. Suppose somebody remembers some evil and foolish pleasure once enjoyed by him; and while he is pondering over that former foolish state, he finds delight in it and becomes again filled with infatuation and greed for it; or he becomes sad and despondent that he cannot enjoy it any more. In consequence of wrongly brooding over such a foolish object, over such a state of ignorance, many evil, unwholesome states arise in his mind. In such a way, avijja may be to unwholesome kamma-formations a condition by way of inducement as object (aramman’upanissaya-paccaya).

Here I have to point out that for a detailed understanding of P.S., we should have to know at least something about those twenty-four different modes in which mental or physical phenomena may be the condition to other mental and physical phenomena. The entire Patthana, the last book of the Abhidhamma Pitaka, which fills six bulky volumes, treats exclusively of these twenty-four conditions, or paccaya, which it first describes and then applies to all the innumerable mental and physical phenomena of existence.5 Here we shall consider only those most prominent ones, which we have already alluded to and applied to avijja, namely: hetu-paccaya, root condition; sahajata-paccaya, condition by way of co-nascence, i.e. co-arising; aññam-añña-paccaya, condition by way of mutuality; upanissaya-paccaya, condition by way of either direct inducement (pakat’ upanissaya), or inducement through object (aramman’ upanissaya). Here, it may be mentioned that all these translations of technical Pali terms are only very inadequate makeshifts, and should be taken as such. I am therefore giving those technical terms repeatedly in both languages, in English as well as in Pali.

The Patthana Commentary compares the hetu-paccaya, or root condition, to the root of a tree. The tree rests on its roots; and it has life only as long as these roots are not destroyed. In the same way, all kammically wholesome and unwholesome kamma-formations are at any time conditioned through the presence and co-nascence, or simultaneity, of their respective wholesome or unwholesome roots. The three unwholesome roots are lobha, dosa, moha, i.e. greed, hate and delusion. The three wholesome roots are alobha, adosa, amoha, i.e. non-greed, or unselfishness; non-hate, or kindness; non-delusion, or knowledge.

Let us now consider sahajata-paccaya, the condition by way of co-nascence. Sahajata, literally means: “arisen together” or “arising together,” hence our term “co-nascence,” or simultaneous arising. This condition of co-nascence applies, above all, to consciousness and its concomitant mental phenomena, such as feeling, perception, volition, sense-impression, attention, etc. For consciousness and all these mental phenomena are mutually conditioned through their simultaneous arising. One cannot arise or exist without the other. All are inseparably associated. Thus if we say that feeling is to consciousness a condition by way of co-nascence, we mean to say that without the simultaneous arising of feeling, consciousness will never be able to arise. In exactly the same way it is with all the other mental phenomena.

Once a well-known Buddhist author, in a discussion with me, to my greatest surprise positively declared that there may be painful feeling without consciousness, for example during a painful operation whilst being under chloroform. This indeed is a most extraordinary blunder. How will it ever be possible to feel pain without being conscious of it? Painful feeling is a mental phenomenon and as such inseparable from consciousness and the other mental phenomena. If we do not perceive pain, and are not conscious of pain, how can we feel pain? Thus consciousness, feeling, perception and all the other mental phenomena are mutually conditioned by way of co-nascence.

Now let us consider upanissaya-paccaya, the condition by way of inducement. This condition is of various kinds, and it forms combinations with certain other conditions.6 It applies to a very wide field, in fact to anything whatsoever. We shall treat this condition here only in a very general way, without making any distinctions. Anything past or future, physical or mental, real or imaginary, may become an inducement to the arising of mental phenomena, or of actions, or occurrences.

So, for example, the Buddha and his Dhamma had been a condition for my coming to the East. So were the Pali scholars whose translations I had read. So was the first Buddhist lecture I had heard in Germany in 1899. Or Nibbana, as object of our thinking, may become an inducement to our joining the Order, or living a pure life, etc. Also all those past thinkers, scientists and artists were by their works and activities an inducement to the developed culture of later generations. Money, as object of our desire, may become an inducement to our making the necessary exertions to get it; or it also may become an inducement to theft and robbery. Faith, knowledge, mental concentration, etc., may be a direct inducement to various noble and unselfish actions. Good or bad friends may be a direct inducement to good or bad conduct. Suitable or unsuitable climate, food, dwelling, etc., may be an inducement to physical health or ill-health; physical health or ill-health to mental health or ill-health. Thus all these things are conditioned through other things by way of inducement.

Now we shall consider arammana-paccaya, the condition by way of object. The object may be either one of the five sense-objects, as visible object, sound, smell, taste, or bodily impression; or it may be any object of the mind. Anything whatever may become the object of mind, be it physical or mental, past, present or future, real or imaginary. Thus the visible object, consisting in differences of color, light and dark, is called the object-condition to eye-consciousness, or the visual sense. Similar it is with the four other senses. Without a physical sense-object no sense-consciousness ever will arise. Further, past evil deeds, through being the object of our thinking, may, as we already have seen, become an inducement, or upanissaya, to repeat the same evil deeds; or they may arouse our disgust or repentance. Thus past evil deeds, by wrong thinking about them, may become an inducement to an immoral life by way of object; and by right thinking about them, the same past evil deeds may become an inducement to a moral life. In a similar way, good deeds, by right thinking about them, may become an inducement to further noble deeds; but by wrong thinking about one’s own good deeds, they may become an inducement to self-conceit and vanity, and many other unwholesome states.7

Hence, also such an immoral thing as avijja may become a condition to noble and wholesome kamma-formations. To show this, let us return to our first proposition: “Through avijja are conditioned the kamma-formations.” How may such an evil state as avijja become a condition to noble and wholesome kamma-formations? It may become so in two ways, either by way of direct inducement, or inducement as mental object. I shall illustrate this statement by an example. At the Buddha’s time many a heretic, induced by mere vanity and delusion, went to the Buddha and tried by dialectics to defeat the Master. However, after a short controversy he was converted: he became a virtuous follower and life-long supporter of the Blessed One, or even attained Arahantship. Here, all these virtuous actions, even the attainment of Arahantship of the new convert, were conditioned by his former avijja as an inducement; had this delusive idea of defeating the Buddha not arisen in his mind, he perhaps might have never in his life even visited the Blessed One. Thus avijja was to his noble and wholesome kamma-formations a condition by way of direct inducement (pakat’-upanissaya). Further, suppose we take avijja as object of our contemplation, considering it as something evil and rejectable, as the root-cause of all misery in the world, then we thereby may produce many noble and wholesome kamma-formations. In this case, avijja is to these wholesome kamma-formations a condition by way of inducement as object (aramman’ upanissaya).8

Before proceeding to the second proposition, I wish to call your attention to the fact that avijja, or ignorance, though the main condition for kamma-formations, is in no way the only condition for them; and so are the kamma-formations to consciousness, etc. Each of the conditionally arising phenomena of P.S. is dependent on various conditions besides those given in the formula, and all may be interrelated and interdependent in manifold ways.

You may have noticed that nearly always I speak only of conditions, and rarely have I used the word “cause.” This word “cause” is often used in a very vague or wrong sense. “Cause” refers really to that thing which — if all the necessary conditions are present — by inner necessity is in time followed by another thing as its “result,” so that already in the cause the future result is lying latent, as it were, just as in the mango seed the future mango tree lies latent.

And just as from the mango seed only a mango tree may result, never an apple tree nor any other tree, just so may a cause result only in just one single thing of a similar character, never in various things nor in things of a different character. If, for example, a man grows furious on being scolded, people generally would say that the scolding man was the cause of the fury. But this is a very vague statement. The cause of the man’s fury really lies in himself, in his own character, not in the person scolding him. The scolder’s words were merely an inducement to the manifestation of his latent fury. The word “cause” signifies only one of the many kinds of conditions, and it should, in Buddhist philosophy, be reserved for kamma, i.e. the rebirth-producing volitional activities bound up with wholesome or unwholesome roots (hetu), constituting the cause of rebirth, and resulting in rebirth as their effect, or vipaka.

2

Herewith we come to the second proposition: Sankhara-paccaya viññanam: “Through the kamma-formations consciousness is conditioned.” In other words: through kamma, or the volitional activities, in the past birth, the conscious life in this present birth is conditioned.

Here the following has to be stated: The five links — consciousness, mental and physical phenomena, the six bases of mental life, impression, and feeling (viññana, nama-rupa, salayatana, phassa, vedana) — refer here only to kamma-resultant (vipaka), neutral phenomena, thus representing the “passive” side of life. However, the five links — ignorance, kamma-formations, craving, clinging, and kammical life-process (avijja, sankhara, tanha, upadana, kamma-bhava) — constitute kamma, thus representing the “active” side of life.9 Hence the five passive links, as consciousness, etc., are to be considered the five results (vipaka), and the five active links, as avijja, etc., the five causes. Thus the life-affirming will, or volition (cetana), manifested in these five kammic causes, is the seed from which all life has sprung, and from which it will spring again in the future. Our second proposition therefore shows that our present conscious life is the result of our kamma-formations produced in the past life, and that without these prenatal kamma-formations as the necessary cause, no conscious life would ever have sprung up in our mother’s womb.

Hence, the kamma-formations are to the rebirth-consciousness of the embryonic being, at its conception in the mother’s womb, a condition by way of kamma, or cause. And so are the kamma-formations to all the morally neutral elements of consciousness. Hence, also the five kinds of sense-consciousness with desirable and agreeable objects are the result, or vipaka, of the prenatal wholesome kamma-formations; and those with undesirable and disagreeable objects are the result of unwholesome kamma-formations.10

3

Now we come to the third proposition, namely: Viññana-paccaya nama-rupam: “Through consciousness the mental and physical phenomena are conditioned.” The meaning of this proposition can be inferred from the Mahanidana Sutta (DN 15), where it is said: “If consciousness (viññana) were not to appear in the mother’s womb, would the mental and physical phenomena (nama-rupa) arise?”11

The mental phenomena (nama) refer here to those seven universal mental phenomena inseparably bound up with all kamma-resultant consciousness, even with the five kinds of sense-consciousness. These seven inseparable universal mental phenomena are: feeling, perception, impression, volition, vitality, attention, concentration; in kamma-resultant mind-consciousness they are increased by three or four further phenomena. The physical phenomena (rupa) refer to this body and its various organs, faculties and functions.12

Now, how are the mental phenomena, or nama, conditioned through consciousness? And how the physical phenomena, or rupa?

Any state of consciousness, as already explained, is to its concomitant mental phenomena, such as feeling, etc., a condition by way of co-nascence, or simultaneous arising (sahajata-paccaya). Consciousness cannot arise and exist without feeling, nor feeling without consciousness; and also all the other mental phenomena which belong to the same state of consciousness are inseparably bound up with it into a single unit, and have no independent existence. These mental phenomena are, as it were, only the different aspects of those units of consciousness which, like lightning, every moment flash up and immediately thereafter disappear forever.

But how may consciousness (viññana) be a condition for the various physical (rupa) phenomena?

In planes of existence where both matter and mind exist, e.g. in the human realm, at the moment of conception consciousness is an absolutely necessary condition for the arising of organic physical phenomena; it is a condition by way of co-nascence. If there is no consciousness, no conception takes place, and no organic material phenomena appear. During life-continuity, however, consciousness (viññana) is to the already arisen physical phenomena (rupa) a condition by way of post-nascence, or later-arising (pacchajata-paccaya), and also by way of nutriment (ahara), because consciousness forms a prop and support for the upkeep of the body. Just as the feeling of hunger is a condition for the feeding and upkeep of this already arisen body, just so is consciousness to this already arisen body a condition and support by its post-nascence, or later arising. If consciousness would rise no more, the physical organs would gradually cease their functioning, lose their faculties, and the body would die. In this way we have to understand the proposition: viññana-paccaya nama-rupam: “Through consciousness the mental and physical phenomena are conditioned.”

4

Now, we come to the fourth proposition: Nama-rupa-paccaya salayatanam: “Through the mental and physical phenomena the six bases of mental life are conditioned.” The first five of these bases are the five physical sense-organs, eye, ear, nose, tongue, body; the sixth base, the mind base (manayatana), is a collective term for the many different classes of consciousness, i.e. for the five kinds of sense-consciousness and the many kinds of mind-consciousness. Hence five bases are physical phenomena, namely, eye, ear, etc., and the sixth base is identical with consciousness.

In which way, now, are the mental and physical phenomena a condition for the five physical bases, or sense-organs, and how for the sixth base, or consciousness? Here we really get four chief questions:

The first question is: How are the mental phenomena (nama) a condition for the five physical bases (ayatana), or sense-organs? The seven inseparable mental phenomena associated with sense-consciousness, such as feeling, perception, etc., are to the five physical bases, or sense-organs, a condition by way of post-nascence, and in other ways. The mental activity during life, namely, is a necessary support to the five physical bases, or sense organs, already produced at birth, as explained before.

The second question is: How are mental phenomena a condition to the mind-base (manayatana) or consciousness? The mental phenomena, as feeling, perception, volition, etc., are at any time to the mind-base, or consciousness, a condition by way of simultaneous arising, or co-nascence (sahajata-paccaya).

You will remember that I repeatedly said that consciousness cannot arise without the co-arising of feeling and the other phenomena, because consciousness and all its mental concomitants are inseparably bound up together, and mutually dependent upon one another. Thus I have shown how the mental phenomena are a condition to the five physical bases or sense-organs, as well as to the mind-base or consciousness (manayatana).

Now we come to the third question: How are the physical (rupa) phenomena a condition for the five physical bases (ayatana), or sense-organs? The four primary physical elements, i.e. the solid, fluid, heat, and motion, are to any of the five physical bases, or sense-organs, at the very moment of their first coming into existence, a condition by way of simultaneous arising (sahajata-paccaya); but during life these four physical elements are to the five bases, or sense-organs, a condition by way of foundation (nissaya) on which the sense-organs are entirely dependent. Further, the physical phenomenon “vitality” (rupa-jivit’ indriya) is to the five bases, or sense-organs, a condition by way of presence (atthi-paccaya), etc.; in other words, the five bases, or sense-organs, depend on the presence of physical life, without which the five sense organs could not exist.

The physical phenomenon “nutrition” (ahara) is to the five physical bases a condition by way of presence, because the five sense-organs can only exist as long as they get their necessary nutriment. Thus I have shown how the physical phenomena, or rupa, are a condition for the five physical bases, or ayatana.

There remains only the fourth question: How are the physical phenomena (rupa) a condition for the mind-base (manayatana), or consciousness? The five physical phenomena, as eye, ear, nose, etc., are to the five kinds of sense-consciousness, i.e. to seeing, hearing, etc., a condition by way of foundation (nissaya) and by way of pre-nascence, presence, etc. These five kinds of sense-consciousness, during life, cannot arise without the pre-arising (purejata) of the five physical sense-organs as their foundation (nissaya); therefore without the pre-arising and presence of the eye, no seeing; without the pre-arising and presence of the ear, no hearing, etc.; so that, if these five sense-organs are destroyed, no corresponding sense-consciousness can arise any longer.

In a similar way is the physical organ of mind the condition for the various stages of mind-consciousness.13 In the canonical books no special physical organ is mentioned by name as the physical foundation of the mind-consciousness, neither the brain nor the heart, though the heart is taught as such by all the commentaries, as well as by the general Buddhist tradition. I think it is my Burmese friend Shwe Zan Aung who first made this fact known in his Compendium of Philosophy.14 For the Buddhist it matters little whether it is the heart or the brain or any other organ that constitutes the physical base of mind.

Thus we have seen how the physical (rupa) phenomena are a condition to the mind-base (manayatana), or consciousness. And herewith we have settled the meaning of the proposition: “Through the mental and physical phenomena the six bases of mental life are conditioned.”

5

Now we come to the fifth propostion: Salayatana-paccaya phasso: “Through the six bases sense-impression is conditioned.”15 In other words: Conditioned through the physical eye is visual impression, conditioned through the ear sound impression, conditioned through the nose smell impression, conditioned through the tongue taste impression, conditioned through the body bodily impression, conditioned through the mind-base or consciousness (manayatana) mental impression.

The five physical bases (ayatana) are to their corresponding sense-impressions (phassa) a condition by way of foundation (nissaya) and by way of pre-nascence (purejata) and in other ways besides. The five sense-organs are not only the foundation for consciousness, as we have seen, but also for all its mental concomitants, hence also for sense-impression. And as these five bases, or sense-organs, have already come into existence at birth, they are called a pre-nascent condition (purejata-paccaya) to the later arising five sense-impressions.

The mind-base or consciousness is at any time to its concomitant sensory or mental impression a condition by way of simultaneous arising or co-nascence, etc. In other words, eye-consciousness arises simultaneously with visual impression, ear-consciousness with sound impression, etc., and mind-consciousness with mental impression.

Also the external physical bases — the five sense-objects, as the visual object, sound, smell, etc. — these too are an indispensable condition to the arising of sense-impression. So visual impression could never arise without the pre-arising of the visible object, sound impression never without the pre-arising of the sound-object, etc. Hence the arising of the five sense-impressions (phassa) depends on the pre-arising of the visual object, the sound-object, etc. Therefore the arising of the five sense-impressions depends just as much on the pre-arising and presence of the five physical sense-objects as on the pre-arising of the five sense-organs, as already stated. Thus sense-impression is also conditioned through the five external physical bases, i.e. through the five sense-objects.

Further, as all the physical sense-objects may also become objects of mind-consciousness, therefore they are also a condition for mind-consciousness as well as for its concomitant phenomena, such as mental impression (phassa), etc. Thus without physical sense-organ and physical sense-object there is no sense-impression; and without mind and mind-object no mental impression. Therefore it is said: “Through the six sense bases sense-impression is conditioned.”

6

Thereafter follows the sixth proposition: Phassa-paccaya vedana: “Through impression feeling is conditioned.” There are six kinds of feeling: feeling associated with visual impression, feeling associated with sound impression, feeling associated with smell impression, feeling associated with taste impression, feeling associated with bodily impression, and feeling associated with mental impression. Bodily feeling may be either agreeable or disagreeable, according to whether it is the result of wholesome or unwholesome kamma. Mental feeling may be either agreeable, i.e. joy, or disagreeable, i.e. sadness; or it may be indifferent. The feelings associated with visual, sound, smell and taste impression, are, as such, always indifferent, but they may have either desirable or undesirable objects, according to the kamma in a previous life. Whatever the feeling may be — pleasant or painful, happy or unhappy or indifferent, whether feeling of body or of mind — any feeling is conditioned either through one of the five sense-impressions or through mental impression. And these impressions (phassa) are a condition to their associated feeling (vedana) by way of co-nascence or simultaneous arising, and in many other ways.

Here you will again remember that all the mental phenomena in one and the same state of consciousness, hence also impression (phassa) and feeling (vedana), are necessarily dependent one upon another by their simultaneous arising, their presence, their association, etc. But to any feeling associated with the different stages of mind-consciousness following upon a sense-impression, the preceding visual or other sense-impression is an inducement by way of proximity (anantar’ upanissaya-paccaya). In other words, the preceding sense-impression is a decisive support, or inducement, to any feeling bound up with the succeeding mind-consciousness.

Thus we have seen how through sensory and mental impression, or phassa, feeling, or vedana, is conditioned.

7

Now comes the seventh proposition: Vedana-paccaya tanha: “Through feeling craving is conditioned.”

Corresponding to the six senses, there are six kinds of craving (tanha), namely: craving for visible objects, craving for sounds, craving for odors, craving for tastes, craving for bodily impressions, craving for mind-objects. If the craving for any of these objects is connected with the desire for sensual enjoyment, it is called “sensuous craving” (kama-tanha). If connected with the belief in eternal personal existence (sassata-ditthi), it is called “craving for existence” (bhava-tanha). If connected with the belief in self-annihilation (uccheda-ditthi) at death, it is called “craving for self-annihilation” (vibhava-tanha).

Any (kamma-resultant and morally) neutral feeling (vedana), whether agreeable, disagreeable or indifferent, whether happy or unhappy feeling, may be to the subsequent craving (tanha) a condition either by way of simple inducement, or of inducement as object. For example, conditioned through pleasurable feeling due to the beautiful appearance of persons or things, there may arise craving for such visible objects. Or conditioned through pleasurable feeling due to pleasant food, craving for tastes may arise. Or thinking of those feelings of pleasure and enjoyment procurable by money, people may become filled with craving for money and pleasure. Or pondering over past pleasures and feelings of happiness, people may again become filled with craving and longing for such pleasures. Or thinking of heavenly bliss and joy, people may become filled with craving for rebirth in such heavenly worlds. In all these cases pleasant feeling (vedana) is to craving (tanha) either a condition by way of simple inducement, or inducement as object of thinking.

But not only agreeable and happy feeling, but even disagreeable and unhappy feeling may become a condition for craving. For example, to a man being tormented with bodily pain or oppressed in mind, the craving may arise to be released from such misery. Thus, through feeling unhappy and dissatisfied with his miserable lot, a poor man, or a beggar, or an outcast, or a sick man, or a prisoner, may become filled with longing and craving for release from such a condition. In all these cases unpleasant and miserable feeling (vedana) of body and mind forms for craving (tanha) a condition by way of inducement, without which such craving might never have arisen. Even expected future feeling of happiness may, by thinking about it, become a mighty incentive, or inducement, to craving. Thus, whatever craving arises depends in some way or other on feeling, be it past, present, or even future feeling. Therefore it is said: Vedana-paccaya tanha: “Through feeling craving is conditioned.”

8

Now we have reached the eighth proposition: Tanha-paccaya upadanam: “Through craving clinging is conditioned.” Upadana, or clinging, is said to be a name for developed or intensified craving. In the texts we find four kinds of clinging: sensuous clinging, clinging to wrong views, clinging to faith in the moral efficacy of mere outward rules and rituals, and clinging to the belief in either an eternal or a temporary ego-entity.16 The first one, sensuous clinging, refers to objects of sensuous enjoyment, while the three other kinds of clinging are connected with wrong views.

Whenever clinging to views or rituals arises, at that very moment also craving must arise; without the simultaneous arising of craving, there would be no such attachments to these views and rituals. Hence craving, or tanha, is for these kinds of clinging, or upadana, a condition by way of co-nascence (sahajata-paccaya). But besides this, craving may be to such kind of clinging also a condition by way of inducement (upanissaya-paccaya). Suppose a fool, who is craving for rebirth in heaven, thinks that by following certain outward moral rules, or by mere belief in a creator, he will attain the object of his desire. So he firmly attaches himself to the practice of mere outward rules and rituals, or to the belief in a creator. In this case, craving is for such kind of clinging a condition by way of inducement, or upanissaya-paccaya.

To sensuous clinging, or kamupadana, however, craving may only be a condition by way of direct inducement. The craving for sense-objects itself gradually develops and turns into strong sensuous clinging and attachment, or kamupadana. For example, craving and desire for objects of sensual enjoyment, for money, food, gambling, drinking, etc. may gradually grow into a strong habit, into a firm attachment and clinging.

Thus I have shown how craving is the condition for clinging. As it is said: Tanha-paccaya upadanam: “Through craving clinging is conditioned.”

9

Next we come to the ninth proposition: Upadana-paccaya bhavo:“Through clinging the process of becoming is conditioned.” Now this process of becoming or existence really consists of two processes: (1) the kamma-process (kamma-bhava), i.e. the kammically active side of life; and (2) the kamma-resultant rebirth-process (upapatti-bhava), i.e. the kammically passive and morally neutral side of life. The kammically active side of this life-process is, as we have seen, represented by five links, namely: ignorance, kamma-formations, craving, clinging, kamma-process (avijja, sankhara, tanha, upadana, kamma-bhava). The passive side of life is represented by five links, namely: consciousness, mental and physical phenomena, the six bases, impression, feeling (viññana, nama-rupa, salayatana, phassa, vedana). Thus the five passive links, as consciousness, etc., refer here only to kamma-resultant phenomena, and not to such as are associated with active kamma. The five active links, as ignorance, etc., are the causes of the five passive links of the future, as kamma-resultant consciousness, etc.; and thus these five passive links are the results of the five active links. In that way, the P.S. may be represented by twenty links: five causes in the past life, and five results in the present one; five causes in the present life, and five results in the future one.17

As it is said in the Visuddhimagga (Chap. XVII):

Five fruits are found in present life;

Five causes which are now produced,

Five fruits are reaped in future life.

Let me here recall to you my definition of the term “cause” as “that which by inner necessity is followed in time by its result.” There are twenty-four modes of conditioning, but only one of them should be called cause, namely, kamma.

Though this kammic cause is in time followed by its result, it nevertheless may depend on (but not be produced by) a preceding kamma-result as its inducement condition. Thus for example, feeling, within the P.S., is a kamma-result; but still, at the same time, it is an inducement-condition to the subsequent arising of craving, which latter is a kamma cause.

Now, let us return to our proposition: upadana-paccaya bhavo:“Through clinging the process of becoming is conditioned,” that is, (1) the kamma-process (kamma-bhava), and thereafter, in the next life, (2) the kamma-resultant rebirth-process (upapatti-bhava). The kamma-process (kamma-bhava) in this ninth proposition is, correctly speaking, a collective name for rebirth-producing volition (cetana) together with all the mental phenomena associated therewith; while the second link, “kamma-formations” (sankhara), designates as such merely rebirth-producing volition. But in reality both links amount to one and the same thing, namely kamma.

Clinging, or upadana, may be an inducement to all kinds of evil and unwholesome kamma. Sensuous clinging, or attachment to sense-objects and sensual enjoyment, may be a direct inducement to murder, robbery, theft, adultery, to envy, hatred, revenge; to many evil actions of body, speech and mind. Clinging to the blind belief in mere outward rules and rituals may lead to self-complacency, mental torpor and stagnation, to contempt of others, presumption, intolerance, fanaticism and cruelty. In all these cases, clinging (upadana) is to the kamma-process (kamma-bhava) a condition by way of inducement, and is a direct inducement to evil volitional activities of body, speech or mind. Moreover, clinging is to any evil kamma-process also a condition by way of simultaneous arising.

Thus I have shown how clinging (upadana) is the condition of the kamma-process (kamma-bhava). Now I shall show how the kamma-process (kamma-bhava) is the condition for the kamma-resultant rebirth-process (upapatti-bhava). Here we come to the tenth proposition.

10

Bhava-paccaya jati:“Through the process of becoming (here kamma-process) rebirth is conditioned.” That means: the kamma-process dominated by the life-affirming volitions (cetana) is the cause of rebirth. Rebirth includes here the entire embryonic process which in the human world begins with conception in the mother’s womb and ends with parturition. Thus kamma volition is the seed from which all life germinates, just as from the mango seed germinates the little mango plant, which in the course of time turns into a mighty mango tree. But how does one know that the kamma-process, or kamma volition, is really the cause of rebirth? The Visuddhimagga (XVII) gives the following answer:

Though the outward conditions at the birth of beings may be absolutely the same, there still can be seen a difference in beings with regard to their character, as wretched or noble, etc. Even though the outward conditions, such as sperm, or blood of father and mother, may be the same, there still can be seen that difference between beings, even if they be twins. This difference cannot be without reason, as it can be noticed at any time, and in any being. It can have no other cause than the pre-natal kamma-process. As also for the life of those beings which have been reborn, no other reason can be found, therefore that difference must be due to the pre-natal kamma-process. Kamma, or volition, indeed, is the cause for the difference among beings with regard to their character, as high, low, etc. Therefore the Buddha has said: “kamma divides beings into high and low.” In this way we should understand that the kammic process is the cause of rebirth.

Thus, according to Buddhism, the present rebirth is the result of the craving, clinging and kamma volitions in the past birth. And the craving, clinging and kamma volitions in this present birth are the cause of future rebirth. But just as in this ever-changing mental and physical process of existence nothing can be found that passes even from one moment to the next, just so no abiding element can be found, no entity, no ego, that would pass from one birth to the next. In this ever repeated process of rebirth, in the absolute sense, no ego-entity is to be found besides these conditionally arising and passing phenomena. Thus, correctly speaking, it is not myself and not my person that is reborn; nor is it another person that is reborn. All such terms as “person” or “individual” or “man” or “I” or “you” or “mine,” etc., do not refer to any real entity; they are merely terms used for convenience sake, in Pali vohara-vacana, “conventional terms”; and there is really nothing to be found beside these conditionally arising and passing mental and physical phenomena. Therefore the Buddha has said:

To believe that the doer of the deed will be the same, as the one who experiences its result (in the next life): this is the one extreme. To believe that the doer of the deed, and the one who experiences its result, are two different persons: this is the other extreme. Both these extremes the Perfect One has avoided and taught the truth that lies in the middle of both, that is: Through ignorance the kamma-formations are conditioned; through the kamma-formations, consciousness (in the subsequent birth); through consciousness, the mental and physical phenomena; through the mental and physical phenomena, the six bases; through the six bases, impression; through impression, feeling; through feeling, craving; through craving, clinging; through clinging, the life-process; through the (kammic) life-process, rebirth; through rebirth, decay and death, sorrow, lamentation, pain, grief and despair. Thus arises this whole mass of suffering.

This phenomenality and egolessness of existence has been beautifully expressed in two verses of the Visuddhimagga:

No one who ever reaps their fruits.

Empty phenomena roll on.

This only is the correct view.

No god nor Brahma can be called

The maker of this wheel of life:

Empty phenomena roll on,

Dependent on conditions all.

In hearing that Buddhism teaches that everything is determined by conditions, someone might come to the conclusion that Buddhism teaches some sort of fatalism, or that man has no free will, or that will is not free. Now, with regard to the two questions: (1) “Has man a free will?” and (2) “Is will free?” the Buddhist will say that both these questions are to be rejected for being wrongly put, and therefore unanswerable.

The first question “Has man a free will?” is to be rejected for the reason that, beside these ever-changing mental and physical phenomena, in the absolute sense no such thing or entity can be found that we could call “man,” so that “man” as such is merely a name without any reality.

The second question “Is will free?” is to be rejected for the reason that “will” is only a momentary mental phenomenon, just like feeling, consciousness, etc., and thus does not yet exist before it arises, and that therefore of a non-existent thing — of a thing which is not — one could, properly speaking, not ask whether it is free or unfree. The only admissible question would be: “Is the arising of will independent of conditions, or is it conditioned?” But the same question would equally apply also to all the other mental phenomena, as well as to all the physical phenomena, in other words, to everything and every occurrence whatever. And the answer would be: Be it “will,” or “feeling,” or any other mental or physical phenomenon, the arising of anything whatsoever depends on conditions; and without these conditions, nothing can ever arise or enter into existence.

According to Buddhism, everything mental and physical happens in accordance with laws and conditions; and if it were otherwise, chaos and blind chance would reign. But such a thing is impossible and contradicts all laws of thinking.

11