21 04 2012 SATURDAY LESSON

588 FREE ONLINE eNālāndā

Research And Practice

UNIVERSITY And THE

BUDDHIST ONLINE GOOD NEWS

LETTER by AWAKEN

ONE WITH AWARENESS

ABHIDHAMMA RAKKHITA through http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org

Dhammapada: Verses and Stories

Dhammapada Verse 141 Practices That Will Not Lead To Purity

Verse

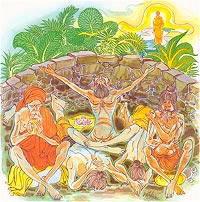

141. Practices That Will Not Lead To Purity

Not going naked, nor matted hair, nor filth,

nor fasting, not sleeping on bare earth,

no penance on heels, nor sweat nor grime

can purify a mortal still overcome by doubt.

Explanation: A person seeking the purification of his soul may

practice the ritual of wandering about naked; or else he may wear turbans; he

may even smear his body with mud; he may even refrain from partaking of food as

an austerity to obtain purity; he may lie on bare earth; or else he may throw

dust all over his body. And again, some may practice a squatting posture. All

of these will not wash a person into spiritual purity if his wavering of mind

is not overcome.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samadhi

Buddhism

Main article: Samādhi (Buddhism)

Samādhi, or concentration of the mind, is the 3rd division of the eightfold path

of the Buddha’s threefold training: wisdom (pañña),

conduct (sīla),

Samādhi (Buddhism) (samādhi) - within which it is developed by samatha

meditation. Some Buddhist schools teach of 40 different object

meditations, according to the Visuddhimagga,

an ancient commentarial text. These objects include meditations on the breath

(anapanasati), loving kindness (metta) and various

colours, earth, fire, etc. (kasiṇa).

Important components of Buddhist

meditation, frequently discussed by the Buddha, are the successively higher

meditative states known as the four jhānas which in the language of the eight-fold path,

are “right concentration”. Right concentration has also been

characterised in the Maha-cattarisaka Sutta as concentration arising due

to the previous seven steps of the noble eightfold path.[20]

Four developments of samādhi

are mentioned in the Pāli Canon:

- Jhāna

- Increased alertness

- Insight into the true nature of phenomena (knowledge

and vision) - Final liberation

Post-canonical Pāli

literature identifies three different types of

samādhi:

- momentary samādhi (khaṇikasamādhi)[21]

- access concentration (upacārasamādhi)

- fixed concentration (appaṇāsamādhi)

Not all types of samādhi are

recommended either. Those which focus and multiply the five hindrances

are not suitable for development.[22]

The Buddhist suttas also mention

that samādhi practitioners may develop supernormal powers (abhijñā, also see siddhis)

and list several that the Buddha developed, but warn that these should not be

allowed to distract the practitioner from the larger goal of complete freedom

from suffering.

The bliss of samādhi is not

the goal of Buddhism; but it remains an important tool in reaching the goal of

enlightenment. Samatha/samādhi meditation and vipassana/insight

meditation are the two wheels of the chariot of the noble eightfold path and

the Buddha strongly recommended developing them both.[23]

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samadhi_%28Buddhism%29

Samadhi (Buddhism)

In Buddhism, samādhi

(Pali / Sanskrit: समाधि)

is mental concentration or composing the mind.

|

Contents [hide] commentarial tradition traditions |

In

the early Suttas

In the Pāli canon

of the Theravada

tradition and the related Āgamas of other early Buddhist schools, samādhi is found in the following contexts:

- In the noble

eightfold path, “right

concentration” (samma-samādhi, S. samyak-samādhi) is

the eighth path factor. - Similarly, samādhi is the second part of the Buddha’s

threefold training: sīla

(morality or virtue), samādhi, and pañña

(wisdom; S. prajña). - In the development of the four jhānas,

the second jhāna (S. dhyāna) is “born” from samādhi

(samādhija).

In Buddhism, samādhi is

traditionally developed by contemplating one of 40 different objects

(mentioned in the Pali canon, explicitly enumerated in the Visuddhimagga),

such as mindfulness of breathing

(anapanasati) and loving kindness (metta).

Upon development of samādhi,

one’s mind becomes purified of defilements, calm, tranquil, and luminous. Once the meditator achieves

a strong and powerful concentration, his mind is ready to penetrate and see

into the ultimate nature of reality, eventually obtaining release from all suffering.

In AN IV.41,[1]

the Buddha identifies four types of concentration development, each with a

different goal:

- a pleasant abiding in this current life - achieved

through concentrative development of the four jhānas - knowledge

and the divine eye - achieved by concentration on light - mindfulness and clear comprehension

- achieved through concentrative mindfulness of the rise and fall of feelings,

perceptions

and thoughts.[2] - the destruction of the taints - achieved through

concentrative mindfulness of the rise and fall of the five aggregates.[3]

The Buddhist suttas mention

that samādhi practitioners may develop supernormal powers (abhijna,

cf. siddhis),

and list several that the Buddha developed, but warn that these should not be

allowed to distract the practitioner from the larger goal of complete freedom

from suffering.

Right concentration

In the Buddhist noble eightfold path, the Buddha explains that

right concentration (Pāli: sammā-samādhi; Skt.: samyak-samādhi)

involves attainment of the successively higher meditative states known as the

four jhānas.[4]

In the Theravada commentarial tradition

According to the Visuddhimagga, samādhi is the “proximate

cause” to the obtainment of wisdom.[5]

Indian Mahāyāna

In the Indian Mahāyāna traditions samādhi is used in the earlier sense, but

“there also appear in Mahayana literature references to a number of

specific samadhi, each with a name and associated benefits, and a number of

which are associated with specific sutras. . . one notes the appearance of

lengthy lists of samadhi names, which one suspects have acquired their own aura

of magical potency. Thus we can find samadhi-name lists, some of considerable

length, in the Aksṣayavamatinirdeśa,

Bodhisattvapiṭaka,

Daśabhhūmīśvara, Gaṇḍavyūha,

Kāraṇḍavyūha,

Mahāvyutpatti, and various Prajñāpāramitā texts. Section 21 of the Mahāvyutpatti

records some 118 samādhi.[6]

This is reflected in the Heart Sutra, a famous Mahāyāna discourse, in

which Avalokiteśvara gives a teaching in the presence of the

Buddha after the Buddha enters “the samādhi which expresses the dharma

called Profound Illumination,” which provides the context for the

teaching.

Likewise, the Samādhirāja Sūtra “declares its main theme

to be a particular samādhi that is supposed to be the key to all elements in

the path and to all the virtues and merits of buddhas and bodhisattvas. This

state of mind, or spiritual practice, is called ‘the samādhi that is manifested

as the sameness of the essential nature of all dharmas’ (sarva-dharma-svabhavā-samatā-vipañcita-samādhi).

One may be tempted to assume that this refers to one particular form or state

of contemplation; however, here the term ’samādhi’ is understood in its

broadest signification. This samādhi is at the same time the cognitive

experience of emptiness, the attainment of the attributes of buddhahood, and the

performance of a variety of practices or daily activities of a

bodhisattva—including service and adoration at the feet of all buddhas. The

word samādhi is also used to mean the sūtra itself. Consequently, we can speak

of an equation, sūtra = samādhi = śūnyatā, underlying the text. In this sense

the title Samādhirāja expresses accurately the content of the

sūtra.”[7]

Zen

|

Part of a series on |

The Five Houses |

|

Caodong / Sōtō |

Doctrine and practice |

|

Buddha-nature |

Principal texts |

|

Diamond |

|

In Zen, the three

trainings (or threefold learning) are presented in the Parable of the Lamp

using the ancient form of a lamp made up of a dish of oil with a lighted wick.

The table (or floor) is the body, the dish is the conscious mind, the oil is

moral conduct (sīla), the wick is unperturbed contemplation (samādhi),

and the flame is intuitive wisdom (prajñā). That which is a

“lamp” does not exist without all of the parts present and

functioning. If there is no oil then the wick is dry and the flame won’t stay

lit. If there is no wick then there is nothing for the flame to be centered

upon and anchored to. If there is no flame then it is not actually a lamp but

just a bowl of oil with a piece of string in it. The wick does not become a

true wick until it is lit, and the flame has no place to light until it has a

wick.[citation needed]

Because of this mutual identity of wick and flame, Huineng, the

renowned Sixth Ancestor of Chinese Chan (Zen), taught in Chapter 4 of the Platform

Sutra that samādhi and prajñā are not different:

Learned Audience, in my system Samadhi and Prajna are fundamental. But do

not be under the wrong impression that these two are independent of each other,

for they are inseparably united and are not two entities. Samadhi is the

quintessence of Prajna, while Prajna is the activity of Samadhi. At the very

moment that we attain Prajna, Samadhi is therewith; and vice versa. If you

understand this principle, you understand the equilibrium of Samadhi and

Prajna. A disciple should not think that there is a distinction between

‘Samadhi begets Prajna’ and ‘Prajna begets Samadhi’. To hold such an opinion

would imply that there are two characteristics in the Dharma.[8]

In Zen, samādhi is the unified state of steady or unperturbed awareness. In

Chapter 5 of the Platform Sutra, Huineng described the role of

samādhi in meditation practice as follows:

When we are free from attachment to all outer objects, the mind will be in

peace. Our Essence of Mind is intrinsically pure, and the reason why we are

perturbed is because we allow ourselves to be carried away by the circumstances

we are in. He who is able to keep his mind unperturbed, irrespective of

circumstances, has attained Samadhi. To be free from attachment to all outer

objects is Dhyana, and to attain inner peace is Samadhi. When we are in a

position to deal with Dhyana and to keep our inner mind in Samadhi, then we are

said to have attained Dhyana and Samadhi.[9]

Intelligence

According to B. Alan Wallace, samādhi is also viewed as

serving as the basis for increasing intelligence.[10]

Wallace also maintains that Buddhist psychology suggests that concentration may

be a factor in the emergence of extraordinary intelligence.[11]

See

also

http://www.lifepositive.com/spirit/meditation/how-to-meditate.asp

INTRODUCTION

MAPPING THE MIND

MIND AND BODY

There`s more to meditation than just closing ones eyes and an

understanding of this technique demands an understanding of our mental realm.

The subtle state of mind, which is the ultimate stage of meditation, requires a

tremendous amount of energy to reach. An absolute harmony between our gross

physical realm, sensual realm and our life energy is the prerequisite of a

meditative state of mind.

Traditional perceptions of our mental make-up are uncommonly useful in

understanding the workings of the mind. According to ayurveda and yoga, both the mind and the body

are made up of the `Five Great Elements` (Panchabhutas) of earth (prithvi),

water (jal), fire (agni or tej), air (vayu) and ether or space (akash).

But in spite of such composition, they have absolutely opposite elemental

structures. While the body is made up of the heavier elements of earth and

water (the ayurvedic kapha or phlegmatic humoral type), it functions through

the lighter elements of fire (pitta or heat humoral type) and air (vata or

vital energy humor). The pitta, fire or heat of the body controls all digestive

processes and the vata, air or vital energy lends its spark to the nervous

system.

The mind, meanwhile, is composed of air and ether (vata humor)—the lighter

elements, which lend mobility and pervasiveness to the mind. And our mental

functions proceed through the heavier elements of fire, water and earth

(pitta—heat and kapha—phlegm). The element of fire lends reason and perception

to the mind, while water and earth lends it emotion and physical

identification. But our mental functions proceed through the heavier elements

of fire, water and earth. While fire lends reason and perception to the mind,

water and earth lends it emotion and physical identification respectively.

Unlike the phlegmatic body, in substance our minds resemble ether—formless and

all pervading. And in motion it resembles air—penetrating, constantly in flux,

effervescent and unpredictable!

MIND AND SPIRIT

The mind (mana) and the energy spirit (prana, chi or life force) have always had an affinity for

each other, being merely the two sides of the same coin. Whatever the mind

engages upon is soon infused with life energy, and conversely, whatever the soul

hungers for instantly engages our attention. As a result, certain aspects of

each are present in the other.

Out of the two, the mind is the finer and more sophisticated version of the

cruder life force or prana—it has a storehouse of its

own energy and vitality. Some aspects of it naturally spills over, flooding the

spirit with thought and intelligence (buddhi). But it is the vital force, which

is inherently a conscious power, finding its expression in the mind, which is

inherently the active force.

Both prana and mana (mind) are vata (vital force) humoral types, composed of

air and ether. But being composed more of the air element rather than the

ether, the prana is more active and energetic—like the wind! On the other hand,

since the degree of ether is more in the composition of the mind, its nature is receptive and passive—like the wide

open spaces.

PREPARING THE MIND

Meditation, especially passive meditation, brings us face to face with our

subconscious. Not unlike opening up a Pandora`s box full of mischief, if we are

not ready to encounter our inner selves, it could end up being a disastrous

experience instead of an enlightening one! And the most vulnerable seem to

be-people with overwhelming anxiety, who are emotionally or psychologically

disturbed, those who have problems accepting reality, people who suffer from

acute paranoia and even those who develop delusions of grandeur from the

altered states of consciousness that meditation tends to produce.

To avoid such psychosis or simply getting lost in our thoughts and ending up

confused and disturbed, it is necessary to begin meditation sessions with formal practice.

Different schools of thought prescribe different methods of such preparation,

but they all agree on the absolute necessity of concentration exercises preceding

meditation. These preparation techniques are as varied as praying, chanting

mantras, performing pranayama or even visualizing. Once the mind becomes

trained for concentration, actual formless or mindfulness meditation can proceed, such as sitting in

silence, practicing self-inquiry or performing devotional meditation.

While Hinduism-based schools of thought insist on a proper sattvic (pure or

ascetic) lifestyle as a primary condition to true meditation, Buddhist

mindfulness meditation prescribes contemplation on the

`Four Protections` and the `Nine Attributes` of the Buddha.

A helpful tip to keep in mind would be that ultimately meditation is all about being at peace with oneself. It cannot perform miracles

out of thin air. It does not solve problems magically. It`s simply a technique,

which acquaints you with the person you really are. And having gained that

timeless knowledge, it is you who will take that first step towards

self-transformation. Remember always that the technique of meditation is nothing more than a tool in your

hands!

HARNESSING THE MIND

Ways of harnessing the ever-changing, ever-shifting mind are as varied as the

different techniques of meditation. But by and large, they all practice mental

exercises, which aim at capturing the very nature of our minds. While the Buddhist

Satipatthana Sutra advices the meditator to be mindful of: the body, feelings,

the mind and mental objects—Patanjali`s Yoga

Sutra talks about the three techniques of: dharana (concentration), dhyana (meditation)

and samadhi (absorption or enlightenment).

Dharana

Dharana, the sixth limb of the Yoga

philosopher Patanjali`s Ashtanga Yoga, literally means `immovable concentration

of the mind`. The essential idea is to hold the concentration or focus of

attention in one direction. This is not the forced concentration of, for

example, solving a difficult mathematics problem; rather dharana is a form of

closer to the state of mind, which could be called receptive concentration.

In practicing dharana, conditions are created for the mind to focus its

attention in one direction instead of radiating out in a million different

directions. Deep contemplation and reflection usually creates the right conditions,

and the focus on a single chosen point becomes more intense. Concentrative

meditative techniques encourage one particular activity of the mind, and the

more intense it becomes the more the other preoccupation of the mind cease to

exist.

The objective in dharana is to steady the mind by focusing its attention upon

some stable entity. Before retracting his senses, on may practice focusing

attention on a single inanimate object. After the mind becomes prepared for

meditation, it is better able to focus efficiently on one subject or point of

experience. Now if the yogi chooses to focus on the center (chakra) of inner

energy flow, he/she can directly experience the physical and mental blocks and

imbalances that remain in his or her system. This ability to concentrate

depends on excellent psychological health and integration and is not an escape

from reality, but rather a movement towards the perception of the true nature of the Self.

Dhyana

Dhyana, the seventh limb of Ashtanga Yoga, means worship, or profound and

abstract religious meditation. It is perfect contemplation. It involves

concentration upon a point of focus with the intention of knowing the truth

about it.

During dhyana, combining clear insights into distinctions between objects and

the subtle layers surrounding intuition further unifies the consciousness. We

learn to differentiate between the mind of the perceiver, the means of

perception, and the objects perceived—between words, their meanings and ideas,

and even between all the levels of natural evolution. We realize that these are

all fused in an undifferentiated continuum. One must apprehend both subject and

object clearly in order to perceive their similarities. Thus dhyana is

apprehension of real identity among apparent differences.

During dharana, the mind becomes unidirectional, while during dhyana, it

becomes ostensibly identified and engaged with the object of focus or

attention. That is why, dharana must precede dhyana, since the mind needs

focusing on a particular object before a connection can be made. If dharana is

the contact, then dhyana is the connection.

Obviously, to focus the attention to one point will not result in insight or

realization. One must identify and become “one with” the object of

contemplation, in order to know for certain the truth about it. In dharana the

consciousness of the practitioner is fixed on one subject, but in dhyana it is

in one flow.

Samadhi

The final step in Ashtanga Yoga

is the attainment of samadhi. When we succeed in becoming so absorbed in

something that our mind becomes completely one with it, we are in a state of

samadhi. Samadhi means “to bring together, to merge”. In samadhi our

personal identities completely disappear. At the moment of samadhi none of that

exists anymore. We become one with the Divine Entity.

During samadhi, we realize what it is to be an identity without differences,

and how a liberated soul enjoys a pure awareness of this pure identity. The

conscious mind drops back into that unconscious oblivion from which it first

emerged. The final stage terminates at the instant the soul is freed. The

absolute and eternal freedom of an isolated soul is beyond all stages and

beyond all time and place. Once freed, it does not return to bondage.

The perfection of samadhi embraces and glorifies all aspects of the self by

subjecting them to the light of understanding. The person capable of samadhi

retains his/her individuality and person, but is free of the emotional

attachment to it.

ASPECTS AND APPROACHES

MEDITATION AS A THERAPY

Meditation has not only been used as an important therapy for psychological and

nervous disorders, from simple insomnia to severe emotional disturbances, but

lately physicians have also prescribed it for curing various physical ailments

as well. It is useful in chronic and debilitating diseases like allergies or

arthritis, in which stress or hypersensitivity of the nervous

system are involved. Regular meditation practices have also been known to

help in dealing with pain and a number of painful diseases, whether

chronic or acute. The act of meditation comes in useful because it helps

the mind to detach itself from all material and physical attachments—and that

is the ultimate cure for all diseases or at least the way to transcend them

when we cannot avoid them.

Research has found meditation, especially Transcendental Meditation, to be

extremely successful in treating physiological problems. Research on

Transcendental Meditation has been conducted at more than 200

universities, hospitals, and research institutions in 27 countries. As a

result, more than 500 research and review papers have been written covering a

wide variety of physiological, psychological, and sociological effects.

Transcendental Meditation allows mental activity to settle

down in a natural way while alertness is maintained and enhanced. Following Transcendental

Meditation, individuals have reported feeling refreshed physically as well as

mentally. The mind has become calmer and more alert, thinking clearer, and

energy levels have increased. Those with busy schedules have noted that

Transcendental Meditation brings increased efficiency in

activity; time is used more effectively. When mental and physical well being

are enhanced, personal relationships also improve, a commonly reported and

valued benefit of Transcendental Meditation.

Physiological research has shown that Transcendental Meditation gives rise to a state of deep rest

characterized by marked reductions in metabolic activity, increased orderliness

and integration of brain functioning, increased cerebral blood flow and

features directly opposite to the physiological and biochemical effects of

stress. Taken together, these studies clearly distinguish the physiology of

Transcendental Meditation from sleep or simple relaxation.

A review of research on behavioral therapy for hypertension concluded that

Transcendental Meditation provides an optimal non-clinical

treatment and preventive program for high blood pressure because the technique:

• produces rapid, clinically significant blood pressure reductions;

• is distinctly more effective than other meditation and relaxation procedures;

• is continued by a high proportion of subjects (in contrast to lower

continuation rates for relaxation techniques and the frequent problem of poor

compliance with anti-hypertensive drugs);

• has documented acceptability and effectiveness in a wide range of

populations;

• is effective in reducing high blood pressure both when used as sole treatment

and when used in concert with medication;

• reduces high blood pressure in `real life` environments outside the clinic;

• is free from harmful side-effects or adverse reactions;

• reduces other cardiovascular risk factors and improves health in a general way.

However, all forms of meditation are not good for everyone, any more

than all foods or herbs are. For this reason both yoga

and ayurveda recommends a proper lifestyle and an

integral approach to meditation that considers both our different

faculties as well as our individual nature.

MEDITATION AND PRAYER

People in the West are more familiar with prayer than meditation. Prayer is a

general term and many types of it exist, but the term usually refers to an

active form of meditation in which we project an

intention—calling on God to help us or our loved ones in some way.

Both ayurveda and yoga

use prayer (prarthana) along with mantra and meditation. Generally mantra is

energized prayer, a prayer or yogic wish directed by special sound patterns or

vibrations of the cosmic Word. Meditation is a silent or contemplative form

of prayer in which there may not be any movement of thought or intention.

Devotional meditation is an intensely personal matter and

is usually conditioned by one`s religious background. Other than worshipping

personal gods and deities who appeal to a particular person`s consciousness,

another important form of devotional worship is-the worship of planetary

deities and cosmic powers behind the forces of time and karma.

AFFIRMATION, AND VISUALIZATION

The use of affirmations goes along with prayer and meditation. Affirmations can

be employed to emphasize our relationship with the divine or our own inner healing powers. People suffering from negative

thoughts about themselves, are often trapped in self-doubt. Affirmations can be

very strengthening in such conditions.

Yet affirmations should lead to action and not substitute for it. To do

anything in life requires a belief that one can do it and

a positive intention to make the effort. In such cases one cannot use the

affirmation as an excuse for inaction.

Visualization goes along with prayer and meditation. One may visualize healed

and improved conditions that one wishes to achieve. One can also direct healing energy to those who are sicker or to

the parts of ones own body that need improvement. Such visualizations usually

employ certain colors and mantras to be directed along with the breath.

Visualizations can also be of deities or beautiful natural scenes to clear the

mental field.

MEDITATION IN TRANSFORMATION

“As a man wishes in his heart, so is he.” We create our karma and

ourselves through our intentions at a deep level. Motivation or will is the

main mental action behind the creation of our beings, the deep-seated

conditionings behind the mind and heart.

While yoga cultivates the will for self-realization,

ayurveda cultivates the will of healing. A

statement of intentions should precede whatever action one decides to

undertake: “I intend to do the following action (in the following manner

for a specific period of time) in order to produce the following result.”

The path to self-transformation is like a plan or a strategy. No action is done

without the seeking of some sort of result. This result

depends upon the intention behind the action, not simply the superficiality of

what we do. Higher or spiritual actions seek a result that is not ego-bound,

like the development of consciousness and the alleviation of suffering for all

beings. Lower actions reflect ego desires—to get what we want; to accomplish,

achieve or gain for ourselves in some way or another. Spiritual motivations

direct us within and help liberate the soul. Ego-based motivations direct us

without and bind us further to the external world.

Self transformational motivation or will implies not only developing our own

will but also allying our will with the forces that can help it achieve its

aim. Therefore it involves a seeking of help, blessings or guidance. Such

motivations are generally projected as various affirmations and vows during

meditational practices.

VARIOUS TECHNIQUES OF MEDITATION

There are many meditation techniques. Some of the techniques

are quite simple and can be picked up with a little practice. Others require

training by an experienced instructor. It is important to note that because of

the effects of meditation on repressed memories and the

resulting psychological impact, a first time meditator may go through some

discomfort initially; hence it is always a good idea to be under the care of a

qualified practitioner as one starts to meditate.

In Christian spiritual training, meditation means thinking with concentration

about some topic. In the Eastern sense, meditation may be viewed as the opposite of

thinking about a topic. Here the objective is to become detached from thoughts

and images and opening up silent gaps between them. The result is a quietening

of our mind and is sometimes called relaxation response. In Christian mystical

practice, this practice is called `contemplation`.

But whatever the technique of meditation, the following aspects are generally

common to all of them:

ATMOSPHERE

The best environment for the practice of meditation is a quiet place with minimum

distractions. It sometimes helps to set up a meditating room with special

pictures, icons, holy books or even burning incense sticks and soothing music in order to infuse the atmosphere with

spiritual energy. It is best to sit in a well ventilated room, which receives

natural light.

ATTITUDE

The best attitude to follow while practicing meditation is that of a receptive observer.

Try to observe either the mind or the immediate physical environment, without

thinking anything in particular. Watch the mind slowly empty itself out.

POSTURE

Assuming a certain posture has been central to many meditation techniques. Classic postures,

integral to Hatha Yoga, are given in the Yoga

Sutras of Patanjali, which codify ancient yogic healing practices. Other postures appear in

the Kum Nye holistic healing system of Tibet, in Islamic prayer,

and in Gurdjieff movements. Posture is considered very important in Zen

Buddhist practice as well.

A major characteristic of prescribed meditation postures in many traditions is that

the spine is kept straight. This is true in Hindu and Buddhist yogas, in the

Christian attitude of kneeling prayer, in the Egyptian sitting position, and in

the Taoist standing meditation of “embracing the

pillar.” People with misalignments may feel uncomfortable in the beginning

when assuming these postures. The spine is put back into a structurally sound

line, and the weight of the body distributed around it in a balanced pattern in

which gravity, not muscular tension, is the primary influence. It is possible,

although it has not been conclusively proven that this postural realignment

affects the state of mind.

In the East, the cross-legged postures, with head and back in vertical line,

are considered ideal for meditation. In the classic the Lotus posture, when the

legs are crossed with the feet on the thighs, right feeling of poised sitting

for meditation is imparted. These postures are

difficult and even painful at first for those who are not familiar with them.

For such inexperienced individuals, two other traditional Eastern postures—half

lotus posture and the Burmese posture—are usually much easier to follow. For

those who prefer to meditate while sitting on a chair, there is the Egyptian

posture.

ELEMENTS OF CONCENTRATION

In Hindu meditative techniques, the object the attention dwells on is often a

mantra, usually a Sanskrit word or syllable. Usually the meditator repeats an

affirmation to increase positive spiritual energies. Alternately prayers or are

often said for calming the mind. Various short rituals are also prescribed before meditation,

such as making offerings of fragrant oils (for earth elements), holy water

(element of water), lamps (fire), incense (air) and flowers or garlands

(ether). These rituals help in cleansing the psychic energy

and preparing the mind for meditation.

In Buddhism, the focus of attention is often the meditator`s own breathing, a

luminous sphere or a translucent Buddha Statue. Some traditional Buddhist

meditations follow forty concentration devices or meditation subjects for tranquilizing the mind

as prescribed by the Buddha These are the ten recollections (anussati), ten

meditations on impurities (asubha) , ten complete objects (kasina), four

immaterial absorption (arupajhana), four divine abiding (brahmavihara), one

perception (ahare patikulasanna) or contemplation of the impurity of material

food, and one defining contemplation (vavatthana) on the Four Elements (earth,

water, fire, and air).

Whether one performs mantra meditation or Buddhist breath meditations, they both fulfill all the

elements required for meditating for relaxation.

TIME

It is always recommended that meditation be practiced daily, twice a day for

best results. Beginners are recommended to meditate for about half an hour

daily. Later when one gets used to the practice, one hour is ideal.

Hindu methods of meditation prescribes about a quarter of an

hour for performing pranayama, the same for mantras and the same for silent or

devotional meditation. What is emphasized is the regularity of practice at all

costs.

http://www.lifepositive.com/spirit/Meditation/meditation.asp

INTRODUCTION

Meditation is an intensely

personal and spiritual experience. The desired purpose of each meditation technique is to channel normal

waking consciousness into a more positive direction by totally transforming

one`s state of mind. To meditate is to turn inwards, to concentrate on the

inner self.

The entire process of meditation usually entails the three stages of

concentration, meditation and enlightenment or absorption. The meditator

starts off by concentrating on a certain point. Once attention gets engaged,

concentration turns into meditation. And through continuous meditation, the

meditator merges with the object of concentration, which might either be the

present moment or the Divine Entity.

In some branches of Indian philosopohy, direct perception from the inner self

(mana) together with perception that is filtered through the five senses

(pancha indriya) form a part of their valid epistemology (pratyaksha jnana).

And this self-realization or self-awareness (as popularized by Paramahansa Yogananda), is nothing but the

knowledge of the “pure being”—the Self.

Humanity is increasingly turning towards various meditative techniques in order

to cope with the increasing stress of modern-day lifestyles. Unable to

locate stability in the outside world, people have directed their gaze inwards

in a bid to attain peace of mind. Modern psychotherapists have

begun to discover various therapeutic benefits of meditation practices. The state of relaxation

and the altered state of consciousness—both induced by meditation—are

especially effective in psychotherapy.

But more than anything else, meditation is being used as a personal growth device these days—for inculcating

a more positive attitude towards life at large.

Meditation is not necessarily a religious practice, but because of its

spiritual element it forms an integral part of most religions. And even though

the basic objective of most meditation styles remain the same and are

performed in a state of inner and outer stillness, they all vary according to

the specific religious framework within which they are placed. Preparation,

posture, length of period of meditation, particular verbal or visual

elements—all contribute to the various forms of meditation. Some of the more

popular methods are, Transcendental Meditation, yoga

nidra, vipassana and mindfulness meditation.

Sikhism

In Sikhism

the word is used to refer to an action that one uses to remember and fix one’s

mind and soul on Waheguru.

The Sri Guru Granth Sahib informs “Remember in

meditation the Almighty Lord, every moment and every instant; meditate on God

in the celestial peace of Samadhi.” (p 508). So to meditate and remember

the Almighty at all times in one’s mind takes the person into a state of Samadhi.

Also “I am attached to God in celestial Samadhi.” (p 865) tells us that by

carrying out the correct practices, the mind reaches a higher plane of

awareness or Samadhi. The Sikh Scriptures advises the Sikh to keep the mind

aware and the consciousness focused on the Lord at all times thus: “The most

worthy Samadhi is to keep the consciousness stable and focused on Him.” (p 932)

The term Samadhi refers to a state of mind rather than a

physical position of the body. Although, it has to said that you can sit in

mediation and also be in a state of Samadhi. The Scriptures explain: “I am

absorbed in celestial Samadhi, lovingly attached to the Lord forever. I live by

singing the Glorious Praises of the Lord” (p 1232) and also “Night and day,

they ravish and enjoy the Lord within their hearts; they are intuitively

absorbed in Samadhi. ||2||” (p 1259). Further, the Sikh Gurus

inform their followers: “Some remain absorbed in Samadhi, their minds fixed

lovingly on the One Lord; they reflect only on the Word of the Shabad.” (p503)

Samadhi

Samadhi (Sanskrit: समाधि) in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism and yogic schools is a higher level of concentrated meditation, or dhyāna.

In the yoga tradition, it is the eighth and final limb identified in the Yoga Sūtras

of Patañjali.

Prabhupada

samadhi

It has been described as a

non-dualistic state of consciousness in which the consciousness of the

experiencing subject becomes one with the experienced object,[1]

and in which the mind becomes still, one-pointed or concentrated[2]

while the person remains conscious. In Buddhism, it can also refer to an

abiding in which mind becomes very still but does not merge with the object of

attention, and is thus able to observe and gain insight into the changing flow

of experience.[3]

In Hinduism, samādhi can also

refer to videha mukti or the complete absorption of the individual consciousness

in the self at the time of death - usually referred to as mahasamādhi.

|

Contents [hide] |

Nomenclature, orthography and etymology

Samadhi (समाधि samādhi,

Hindi pronunciation: [səˈmaːd̪ʱi])

is the state of consciousness induced by complete meditation. The term’s etymology

involves “sam” (together or integrated), “ā”

(towards), and “dhā” (to get, to hold). Thus the result might

be seen to be “to acquire integration or wholeness, or truth” (samāpatti).

Another possible etymological analysis of “samādhi” is “samā”

(even) and “dhi” (intellect), a state of total equilibrium

(”samā“) of a detached intellect (”dhi“).

Rhys Davis[4]

holds that the first attested usage of the term samādhi in Sanskrit

literature was in the Maitri Upanishad.[5]

Hinduism

Samādhi is the main subject of the first part of the Yoga Sūtras

called Samādhi-pada. Vyāsa, a major figure in Hinduism and one of the traditional

authors of the Mahābharata, says in his commentary on verse 1.1 of the Yoga Sūtras

that “yoga is samādhi.”[6]

This is generally interpreted to mean that samādhi is a state of

complete control (samadhana) over the functions and distractions of

consciousness.

Samādhi is described in different

ways within Hinduism such as the state of being aware of one’s existence

without thinking, in a state of undifferentiated “beingness” or as an

altered state of consciousness that is characterized by bliss (ānanda) and joy (sukha). Nisargadatta Maharaj describes the state in the following manner:

When you say you sit for meditation,

the first thing to be done is understand that it is not this body

identification that is sitting for meditation, but this knowledge ‘I am’, this

consciousness, which is sitting in meditation and is meditating on itself. When

this is finally understood, then it becomes easy. When this consciousness, this

conscious presence, merges in itself, the state of ‘Samadhi’ ensues. It is the

conceptual feeling that I exist that disappears and merges into the beingness

itself. So this conscious presence also gets merged into that knowledge, that

beingness – that is ‘Samadhi’.

—[7]

The initial experience of it is

enlightenment and it is the beginning of the process of meditating to attain

self-realization (tapas). “There is a difference between the

enlightenment of samādhi and self-realization. When a person achieves

enlightenment, that person starts doing tapas to realize the self.”[8]

According to Patañjali[9]

samādhi has three different categories:

- Savikalpa

- This is an interface of trans meditation[clarification

needed] and higher awareness state, asamprajñata. The

state is so named because mind retains its consciousness, which is why in savikalpa

samādhi one can experience guessing (vitarka), thought (vicāra),

bliss (ānanda) and self-awareness (asmita).[9]

In Sanskrit,

“kalpa” means “imagination”. Vikalpa (an

etymological derivation of which could be ‘विशेषः कल्पः विकल्पः।‘) connotes imagination. Patañjali in the Yoga Sūtras

defines “vikalpa” saying: ‘शब्द-ज्ञानानुपाति वस्तु-शून्यो-विकल्पः।‘. “Sa” is a prefix which means

“with”. So “savikalpa” means “with vikalpa”

or “with imagination”. Ramana Maharshi

defines “savikalpa samādhi” as, “holding on to

reality with effort”.[10] - Asamprajñata

is a step forward from savikalpa. According to Patañjali,[9]

asamprajñata is a higher awareness state with absence of gross

awareness.[11] - Nirvikalpa

or sanjeevan - This is the highest transcendent state of

consciousness. In this state there is no longer mind, duality, a

subject-object relationship or experience.[12]

Upon entering nirvikalpa samādhi, the differences we saw before have faded and we can

see everything as one. In this condition nothing but pure awareness

remains and nothing detracts from wholeness and perfection.

Entering samādhi initially

takes great willpower and maintaining it takes even more will. The beginning

stages of samādhi (laya and savikalpa samādhi) are only

temporary. By “effort” it is not meant that the mind has to work

more. Instead, it means work to control the mind and release the self. Note

that normal levels of meditation (mostly the lower levels) can be held

automatically, as in “being in the state of meditation” rather than

overtly “meditating.”[clarification

needed] The ability to obtain positive results from meditation is

much more difficult than simply meditating.[clarification

needed] It is recommended to find a qualified spiritual master (guru or yogi) who can teach a meditator about the workings of the mind.

As one self-realized yogi explained, “You can meditate but after some time

you will get stuck at some point. That is the time you need a guru. Otherwise,

without a Guru, there is no chance.”[13]

Samādhi is the only stable unchanging reality; all else is

ever-changing and does not bring everlasting peace or happiness.

Staying in nirvikalpa samādhi

is effortless but even from this condition one must eventually return to

ego-consciousness. Otherwise this highest level of samādhi leads to nirvāṇa, which means total unity, the logical end of individual

identity and also death of the body. However, it is entirely possible to stay

in nirvikalpa samādhi and yet be fully functional in this world. This

condition is known as sahājā nirvikalpa samādhi or sahājā samādhi.

According to Ramana Maharshi, “Remaining in the primal, pure natural state without

effort is sahaja nirvikalpa samadhi“.[10]

Bhakti

The Vaishnava

Bhakti Schools

of Yoga define samādhi

as “complete absorption into the object of one’s love (Krishna).”

Rather than thinking of “nothing,” true samādhi is said to be

achieved only when one has pure, unmotivated love of God. Thus samādhi

can be entered into through meditation on the personal form of God. Even while

performing daily activities a practitioner can strive for full samādhi.

“Anyone who is thinking of

Krishna always within himself, he is first-class yogi.” If you want

perfection in yoga system, don’t be satisfied only by practicing a course of

asana. You have to go further. Actually, the perfection of yoga system means

when you are in samadhi, always thinking of the Visnu form of the Lord within

your heart, without being disturbed… Controlling all the senses and the mind.

You have to control the mind, control the senses, and concentrate everything on

the form of Vishnu.

That is called perfection of yoga” - A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami

Prabhupada[14]

“Meditation means to absorb

your mind in the Supreme Personality of Godhead. That is meditation, real

meditation. In all the standard scriptures and in yoga practice formula, the

whole aim is to concentrate one’s mind in the Supreme Personality of Godhead.

That is called samadhi, samadhi, ecstasy. So that ecstasy is immediately

brought by this chanting process. You begin chanting and hear

for the few seconds or few minutes: you immediately become on the platform of

ecstasy.” - A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada[15]

Bhava Samadhi is a state of

ecstatic consciousness that can sometimes be a seemingly spontaneous

experience, but is recognized generally to be the culmination of long periods

of devotional practices.[16]

Shivabalayogi explained that bhava samādhi awakens spiritual awareness,

brings about healing, and deepens meditation.[17]bhava

samadhi” denotes an advanced spiritual state in which the emotions of

the mind are channelled into one-pointed concentration and the practitioner

experiences devotional ecstasy. Bhava

samadhi has been experienced by notable figures in Indian spiritual

history, including Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa and some of his

disciples, Chaitanya

Mahaprabhu and his chief disciple Nityananda, Mirabai and

numerous saints in the bhakti tradition.[18]

Leaving the body

See also: Sallekhana

Yogis are said to attain the final liberation or videha

mukti after leaving their bodies at the time of death. It is at this

time that the soul knows a complete and unbroken union with the divine, and,

being free from the limitations of the body, merges effortlessly into the

transcendent Self. Mahāsamādhi (literally great samādhi) is a

term often used for this final absorption into the Self at death.

Mausoleum

Anandamayi Ma Samadhi Mandir, Kankhal, Haridwar

Samādhi mandir is also the Hindi name for a

temple commemorating the dead (similar to a mausoleum),

which may or may not contain the body of the deceased. Samādhi sites are

often built in this way to honour people regarded as saints or gurus in Hindu religious

traditions, wherein such souls are said to have passed into mahā-samādhi,

(or were already in) samādhi at the time of death.

I.K. Taimni

I. K. Taimni, in The Science of

Yoga,[19]

Taimni’s commentary on Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, provides a lucid and precise

understanding of samadhi. In simple terms, Taimni defines samadhi as

“knowing by becoming”. Samadhi, as pointed out above, is the eighth

arm of Patanjali’s Ashtanga (eight limbed) yoga. The last three of the eight

limbs are called Antaranga, or Internal yoga, meaning they occur solely in the

mind of the yogin. The three limbs are: dharana, dhyana and samadhi. Together,

the three are collectively called samyama. Dharana, dhyana and samadhi are sometimes

translated as concentration, contemplation, and meditation, respectively. These

translations do not shed any light on the nature of dharana, dhyana and

samadhi. Dharana, dhyana and samadhi are altered states of consciousness and

have no direct counter-part in normal waking experience, according to Taimni’s

explanation of them.

According to Taimni, dharana, dhyana and samadhi form a graded series.

Dharana. In dharana, the mind

learns to focus on a single object of thought. The object of focus is called a

pratyaya. In dharana, the yogi learns to prevent other thoughts from intruding

on focusing awareness on the pratyaya.

Dhyana. Over time and with

practice, the yogin learns to sustain awareness of only the pratyaya, thereby

dharana transforms into dhyana. In dhyana, the yogin comes to realize the

triplicity of perceiver (the yogin), perceived (the pratyaya) and the act of

perceiving. The new element added to the practice of dhyana, that distinguish

it from dharana is the yogin learns to minimize the perceiver element of this

triplicity. In this fashion, dhyana is the gradual minimization of the

perceiver, or the fusion of the observer with the observed (the pratyaya).

Samadhi. When the yogin can: (1)

sustain focus on the pratyaya for an extended period of time, and (2) minimize

his or her self-consciousness during the practice, then dhyana transforms into

samadhi. In this fashion then, the yogin becomes fused with the pratyaya.

Patnajali compares this to placing a transparent jewel on a colored surface: the

jewel takes on the color of the surface. Similarly, in samadhi, the

consciousness of the yogin fuses with the object of thought, the pratyaya. The

pratyaya is like the colored surface, and the yogin’s consciousness is like the

transparent jewel.

Samadhi can be compared to normal thought as a laser beam can be compared to

normal light. Normal light is diffuse. A laser beam is highly concentrated

light. The laser beam contains power that normal light does not. Similarly,

samadhi is the mind in its most concentrated state. The mind in samadhi possess

power than a normal mind does not. This power is used by the yogin to reveal

the essence of the pratyaya. This essence is called the artha of the pratyaya.

The release of the artha of the pratyaya is similar to cracking open the shell

of a seed to discover the essential elements of the seed, the genetic material,

protected by the shell.

Once perfected, samadhi is the main tool used by a yogin to penetrate into

the deeper layers of consciousness and seek the center of the yogin’s

consciousness. Upon finding this center, the final act is using a variant form

of samadhi, called dharma mega samadhi, to penetrate the center of

consciousness and emerge through this center into Kaivalya. Kaivalya is the

term used by Patanjali to designate the state of Absolute consciousness free

from all fetters and limitations.

Thus it can be seen that, according to Taimni’s interpretation of the Yoga

Sutras, samadhi is the main tool the yogin uses to achieve the end goal of

yoga, the joining of the individual self with the Universal Absolute.

Analogous concepts

According to the book “God Speaks” by Meher Baba,

the Sufi words fana-fillah

and baqa-billah are analogous to nirvikalpa samādhi and sahajā samādhi

respectively.[24]

See

also

- Baqaa

- Bhakti Yoga

- Egolessness

- Fanaa

- Jangama dhyana

- Jnana Yoga

- Kriya Yoga

- Mantra

- Meditation

- Raja Yoga

- Sahaja Yoga

- Turiya