What is demand-driven innovation?

“As the populations moves toward the 9 billion mark and the Earth’s

climate becomes increasingly variable, we face growing social and

environmental problems,” is the opening text for Demand-Driven.org,

a new site for the international development community. ”Solving these

problems entails understanding what low-income communities need and

want. Developing solutions to tackle these global problems requires

thinking early about how the product or service will get to market, how

the private sector might get involved, and how to leverage diferent

sources of finance.”

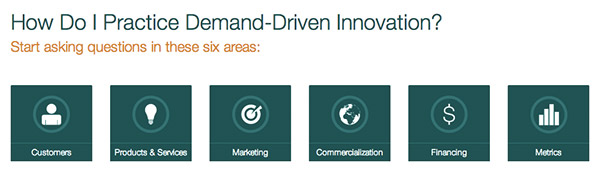

With support from the World Bank, GATD, Catapult Design and Alana Conner Communications kicked

off development of Demand-Driven.org as a resource for innovators

tackling challenges in low-income communities. Intended for funders,

policymakers and practitioners, the new site serves as a prompt for

discussion around six areas affecting these innovators: customers,

products & services, marketing, commercialization, financing and

metrics.

Using stories from on-the-ground innovators interviewed in Rwanda,

Kenya, India, Uganda, Ghana, Nigeria, the UK and beyond, the site

illustrates how organizations and individuals successfully (and

sometimes not so successfully) overcame the roadblocks in the design and

delivery of new products and new services.

We welcome your input, your stories, and ideas for

additional prompts. Tell us what resources the industry needs to be

successful at instigating change. We’d love to hear from you!

Catapult Labs 2013 in less than two minutes

If you missed Catapult Labs this year, here’s a quick rundown of the day in 99 photos. See you next year in San Francisco and on the Navajo Nation!

Catapult Labs 2013 from Catapult Design on Vimeo.

Photos by Justin Halgren Photography

Catapult receives grant to support entrepreneurial design event on the Navajo Nation

National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) Acting Chairman Joan Shigekawa

announced today that Catapult Design, a product and service design firm

based in San Francisco, is one of 817 nonprofit organizations nationwide

to receive an NEA Art Works grant. Catapult Design’s grant will support

the expansion of its design and innovation education program to the

Navajo Nation in Arizona.

In 2012 Catapult Design hosted its first design event, Catapult Labs,

in San Francisco with the goal of exposing attendees to new design

tools and methods that spark and support positive social change. With

NEA funds, Catapult will host this event on the Navajo Nation in 2014.

The event will bring together designers and entrepreneurs from Silicon

Valley and the Navajo Nation to build networks, activate communities,

and spark entrepreneurial social innovation.

In 2010, the unemployment rate on the Navajo Nation – which crosses

Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah – spanned 40-70%, compared to 9.6% across

the U.S. Despite resource-rich land, the largest tribal landmass in the

country, and a viable workforce of 180,500 people, the growth of Navajo

small businesses is less than half the growth rate for the U.S.

By engaging local partners, such as the Rural Entrepreneurship

Institute in New Mexico, Catapult will assemble Native American youth

and budding entrepreneurs who want to turn their ideas into realized

solutions for community and economic development on tribal lands.

“It’s an opportunity to cross-pollinate methods and ideas in one of

the most entrepreneurially thriving places in the world – Silicon Valley

– with one of the most entrepreneurially challenged places in the world

– the Navajo Nation. Innovation exists in both places through a

completely different lens,” says Heather Fleming, CEO of Catapult Design

who is also originally from the Navajo Nation. “We’re eager to help

connect and support folks with big ideas for their community.”

Acting Chairman Shigekawa said, “The National Endowment for the Arts

is proud to support these exciting and diverse arts projects that will

take place throughout the United States. Whether it is through a focus

on education, engagement, or innovation, these projects all contribute

to vibrant communities and memorable opportunities for the public to

engage with the arts.”

For a complete listing of projects recommended for Art Works grant support, please visit the NEA website at arts.gov.

Five Skills Designers Have That Global Development Needs

“Development is being disrupted,” says Raj Kumar, President of DevEx,

a site devoted to helping the international development community

deliver foreign aid more efficiently and effectively. Beyond the buzz

generated by the “social entrepreneurship” and “impact investing”

communities, I’ve seen a significant shift coming from traditional aid

agencies in the past two years.

In 2010, USAID, the agency responsible for administering US foreign aid, launched the first-of-its-kind Development Innovation Ventures

quarterly grant program. Its funding model is inspired by traditional

venture capital and the focus is on scalable and entrepreneurial

solutions to poverty alleviation. Similarly, in 2012 the World Bank

hired a former Silicon Valley Google.org director to lead their new

“Innovation Labs.” UNICEF and the Inter-American Development Bank have

also launched their own “Innovation Labs” with similar goals of promoting open-dialogue, new methods, and cross-pollination of models that enable innovative activity.

So with all this talk about “innovation,” where are the designers,

the technologists, and the entrepreneurs? The folks behind these

initiatives are still folks with international and economic development

backgrounds, economics and finance. If they’re serious about innovative

approaches, it’s time creative problem solvers are added to the

equation. Specifically, here are five strengths designers have that the

development industry direly needs:

1. We are systems thinkers.

The problems that plague our world are complex, interwoven, and

multifaceted. As designers, we solve problems through a combination of

analytic and creative thinking. Many of the best designers I know are

themselves multi-faceted and multi-disciplinary. In addition to a design

degree, they’re also engineers or MBAs or economists. It takes both

sides of the brain to generate solutions to social challenges.

2. Fresh eyes.

Einstein’s “We can’t solve the world’s problems by using the same

type of thinking we used when we created them,” couldn’t ring more true.

Many of the social issues we’re fighting today have existed for decades

and consistently been addressing using old mechanisms—policy, aid, and

philanthropy. We are long overdue for fresh thinking to old problems.

3. We have a prototyping culture.

We make a lot of mistakes in development—mistakes that sometimes

negatively impact people with everything to lose; mistakes that could

potentially be avoided if the development sector fostered a culture of

iteration and refining ideas before rushing to scale. Instead, I see a

lot of money going towards untested ideas or worse yet, “solutions in

search of a problem.”

4. We focus on people.

Many decisions made today that affect the poor are made by people

completely removed from their issues. A designer’s viewpoint, driven by

an understanding of the needs of people or end-users, is completely

unique and lacking within the development sector. The key to better

policy, better products, and better public services is rooted in

understanding of the key players and what motivates them.

5. We create capacity.

We build things. We build products, services, websites—and by doing

so we are intrinsically building the capacity of those who make,

distribute, sell, or use what we create. On a fundamental level, giving

people access to tools that enhance their capacity is what drives

economic development. We play a central role in creating those tools

that are useful, relevant, and meaningful.

$22.8 billion of our projected fiscal budget is earmarked for

poverty-reduction activity in 2013. Traditionally, international

development agencies use the amount of the money put towards poverty

alleviation as a metric for efficacy. I’m hoping the next few years

shift that metric towards understanding underlying problems and funding

new solutions that address those problems. In order to do that, we need a

new breed of development thinkers. The next generation of designers is

inspired by careers that provide meaning and impact. Now is the perfect

time for the development sector to start connecting the dots.

“Reaching the doorsteps of the poor” with Living Goods

Photo by Living Goods

To appreciate companies like Living Goods, you have to transport

yourself to a world without Walmart, UPS, or a local Walgreens pharmacy.

Imagine if in order to purchase an item as simple as soap, you had to

spend more money on transport than the cost of the product alone, not to

mention the time spent away from productive work. As Chuck Slaughter

points out in a recent article in The Economist, “Distribution is often the missing link between design and impact.”

We couldn’t agree more. One of the most common hurdles social

entrepreneurs with exciting product ideas face is the lack of formal

distribution channels in rural markets. The prospect of creating your

own channels, especially without a proven market, is daunting if not

impossible.

Since starting in 2007, Living Goods has tackled this challenge in

Uganda by training local sales agents to deliver life-changing products

such as anti-malaria treatments, fortified foods, solar lamps, clean

burning cook stoves, and sanitary pads. The analogy they use is “Avon

ladies”, where CEO Chuck Slaughter worked for a few years in order to

understand the franchise model.

“Nothing about what we do is a handout,” says Chuck in a recent interview. “It’s really about empowerment. It’s about giving people the tools they need to improve on their own.”

With more than 1,000 profitable agents in Uganda, Living Goods will

expand its service to Kenya this year. The opportunity is huge. And

with a growing customer base, Living Goods is now in a position to build

on their brand through their own product line. In 2012 they began

discussions with a few major packaged goods companies about

manufacturing fortified foods for infants to combat malnutrition. But

big business moves slowly. And Living Goods is eager to address this

critical human need and fill this gap in the market. Enter Catapult

Design.

Catapult and Living Goods have teamed up to develop a new nutritional

product for distribution in Uganda and Kenya. Leveraging expertise from

entities such as GAIN and Technoserve, Catapult will work with the

Ugandan sales agents, Living Goods customers, and East African

manufacturers to prototype a packaged food at a price point appropriate

for rural households.

The end goal? Living Goods’ ultimate goal: to show that companies

can deliver profits and positive human impact. “A sustainable

distribution platform that can meet the needs of the poor — that’s the

holy grail,” say Chuck to The New York Times.

Stay tuned for progress on the partnership with Living Goods.

What Do You Have in Common with a Low-Income Indian Mother? More Than You Think

Photo Courtesy of the Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves

Imagine this: You wake up early, as always, to prepare breakfast for

your family. Wiping the sleep from your eyes you shuffle to the kitchen

and light the stove—out comes billowing black smoke that immediately

fills the room. Business as usual. You put on a pot of water to boil

porridge. Your 3-year-old is now awake and comes over to watch you cook.

They lean against soot-blackened walls and cough chronically as you

continue cooking, learning how it’s done. You try to keep low, below the

acrid smoke, as you feed the stove and stir the porridge, eyes

watering. Breakfast should be ready soon, which is good because the rest

of the family is waking up. As the porridge simmers, your mind turns to

the day ahead—fetching wood, carrying water, going to market, preparing

dinner… Overhead the coal-black thatch roof crouches over you,

suspended on a pillow of smoke, but you pay it no mind. After all, it’s

been that way since before you were born.

Smoke is known to be toxic. It kills young children around the world

at a rate exceeded only by the drama and trauma of childbirth. The

negative impact on adult heart disease and life expectancy from cooking

in kitchens such as this is well documented.

To those who understand the ramifications of breathing smoke and who,

importantly, have exposure to other cooking methods, the harm is

literally written on the soot-covered wall.

But that’s just the point. You, and the billions of other people who

routinely cook their meals in this fashion, don’t know any other way.

Your mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother all cooked like this.

And even when you and your peers are informed as to the harm of your

approach, you persist. It seems far-fetched to think that a pervasive

and ancient cultural practice could be such a vicious killer. Besides,

it’s what you know and are comfortable with—it’s what everyone does. So

you continue, and the lungs of your family continue to fill with smoke.

Unfortunately, people are not rational actors; we are trained

creatures of habit, molded and formed by our culture and personal

experiences. Whether you’re a recent heart attack survivor who continues

to live on a diet of Big Macs, or an overweight office-worker who

watches hour after hour of television, you, and the rest of humanity,

persist with habitual behaviors that are illogical and clearly damaging.

It’s obvious to an outside observer, and maybe even to yourself, but

that doesn’t stop you. Despite infinite public service announcements and

articles about the harms of a poor diet or inactivity (to name only a

couple of common issues) people resist changes to their accustomed

behaviors almost as if their lives depended on it. Which, in a fashion,

they do. Their way of life depends on their habitual patterns. And it is

this habituated behavior that we, as designers and engineers striving

to address social issues, must overcome.

But how do we do this? How do we attempt to tackle millennia of

culturally instructed behavior? Contemporary psychological theories of

behavior change, such as the Theory of Planned Behavior,

tell us that people’s behaviors are based on attitudes, beliefs, and

values and that changes in behavior rely on changes in these underlying

attributes. Interestingly, the field of human-centered design also

emphasizes understanding human values as an integral part of the design

process. As David Kelley, founder of IDEO, tells us,

“The way to do it is to go out and figure out what humans actually

value.” In the field of design for social impact the theories of

behavior change and human-centered design converge and they both clearly

indicate that an understanding of values is key: successful designs

appeal to people’s values and so do successful behavioral change

campaigns.

So how do we understand peoples’ values? Again, David Kelley clues us in:

“At some point by observing these people and building

empathy for them you start to have insights about them. “Oh, they really

do value this.” It’s not obvious at first that that’s what they really

value. They say they really don’t do something but it turns out they

actually do when you observe them.”

If the way to understand values is through empathy, how do we build empathy? I touched on this subject in my last blog post, Design Skills and Life,

but I haven’t been able to stop thinking about these questions because

they are central to all of our work at Catapult. So I’m taking you with

me as I chip away at understanding the process of empathizing.

Daniel Goleman, author of Emotional Intelligence tells us that,

“Self-awareness is the first component of emotional

intelligence – which makes sense when one considers that the Delphic

oracle gave the advice to “know thyself” thousands of years ago.

Self-awareness means having a deep understanding of one’s emotions,

strengths, weaknesses, needs, and drives.”

Self-awareness, being the first component of emotional intelligence,

forms the foundation for the other components (self-regulation,

motivation, empathy, and social skill). Without self-awareness we

struggle to empathize, if we can’t empathize we will find it difficult

to understand people’s values, and if we can’t understand peoples values

we won’t know how to design meaningful products for them in such a way

that their behaviors change.

Photo Courtesy of Confessions of a Shopaholic

Do you, like the Indian mother in our example, understand why you

persist in behaviors or beliefs that are unhelpful? Do you understand

why you keep smoking, struggle with direct communication, judge people

who are uneducated, and all of the other myriad things that you do that

you would love to change in your life but don’t? If you understood why

you can’t stop eating, might it help you relate to people who can’t stop

shopping? If you understood why tradition keeps you cooking the same

gross holiday dish even though no one likes it, might it help you

understand why a mother might continue cooking over a smoky fire?

Let me take an example from my own life. I live in San Francisco, one

of the best cities in the US for public transportation. I also own a

car despite being an ardent believer in global warming, that the world

is headed toward serious environmental catastrophe, and that by

regularly driving my car I am directly contributing to the problem,

threatening the lives of millions. But I can’t bring myself to ditch the

car. Why? What am I valuing that is holding me back? It has something

to do with comfort (it’s convenient and easy) and familiarity (my family

has always had automobiles). If I was to get rid of my car I would have

to plan much more (requiring significant extra effort to plan bus

routes or rent cars for both routine errands and long trips) and it

would require a non-trivial reworking of my lifestyle (how would I get

my weekly groceries or go for weekend hikes?). I would also have to

explain to my friends and family why I am making the change and that

would require confrontation, something with which I perpetually struggle

(another family trait).

So, how can I relate to the Indian mother in our example? Can I

understand that it might be easier to just keep doing what she has

always done? Can I relate to the fact that change takes effort

(modifying cooking habits) and involves confrontation (explaining to her

family why she needs to get a different stove)? Can I take that

relating and integrate it into the products on which I work? Maybe we

can design a stove that can fit into her life in such a way that her

cooking habits don’t have to change. Or perhaps we can design a program

that reduces the family confrontation by making it more affordable. This

is where things can get creative as we explore ways of building our

products around the values of our end user.

By attempting to look inward at my own experience in order to see

what I have in common with a low-income Indian mother, I hope this post

has opened a door to you finding your own personal way to connect with

her. This is how we uncover the values that will give rise to solutions.

To paraphrase Daniel Goleman, it is by understanding yourself that

you begin to understand others. By feeling how your own hindrances are

active in your life you can start to empathize with other people who

struggle to make changes. Through understanding and empathy you can see

what might be holding others back (their needs, wants, values,

capabilities, beliefs, fears, etc.) and what they might require in order

to change their behavior. Cultivating these capacities of understanding

and empathy will allow you to work with others in an appropriate,

considerate, and effective fashion. And that’s what design is: working

with people to create tools that serve them in a meaningful way.

So I ask, all of you would-be designers and change makers, how well do you know yourself?

Think Like MacGuyver: Creative Resilience in the Developing World

Raise your hand if you’re familiar with the TV show MacGyver.

The main character is truly a phenomenal human being. The plot of the

60-minute show is pretty consistent: He’s a secret agent whose specialty

is finagling himself out of the most impossible situations. He had an

uncanny ability of taking everyday objects from his immediate

surroundings and transforming them to solve problems. He could turn a

coffin into a get-away jet ski. He could disarm a nuclear warhead using

only a safety pin. In one of my favorite episodes he builds a

long-distance bomb using a rubber glove, a gas pipe, a light bulb, and

shards from a toilet bowl. He’s a universal symbol for resourcefulness,

ingenuity, and creativity.

If you deconstruct his actions in every episode, there are four

factors that enable his success. I’ve called them the four enablers of

creativity:

1. He is a do-er. It’s easy for teams to sidestep creativity when

taking on a new endeavor by quibbling over objectives. Ambiguity is

uncomfortable. MacGyver uses action to work through the ambiguity. He

could sit and have a discussion about his options, or create a tradeoff

matrix, but he chooses to learn by doing.

2. His resources are defined. One of the first things we do at the

start of a design project is figure out what we know and what we don’t

know. We make constraints. It’s a contrast to what we associate with

creativity—which is blue-sky, free-thinking, no rules. But the lack of

constraints, or lack of a creative process, is in fact a deterrent to

producing innovative results.

3. His goal is clear and a deadline is imminent. For MacGyver, the

bomb is always ticking down. He has a defined amount of time. Failure is

not an option. It’s similar to that feeling you get the night before a

deadline, when the creative adrenaline rushes in at 2 a.m. The pressure

is necessary to drive action.

4. He doesn’t have to ask for permission. Imagine if MacGyver had to

stop with 15 seconds left on the bomb ticker to get clearance to use a

set of pliers. Creating an enabling environment—tools on hand, creative

‘places,’ ‘time’ for creativity, diversity in thought—is what helps him

get the job done.

There are a number of websites dedicated to debunking this TV

character’s ingenuity, but he’s not entirely fiction. There are

real-life MacGyvers throughout the developing world exhibiting the same

resourcefulness and creativity, as well as entrepreneurship. This past

November I bought a Rwandan-made LED lamp (pictured above) for 800 RWF

(about $1.25 USD). It’s simple—some re-purposed wood, spent batteries

from a radio, an LED, and some wire. There’s not even an on/ off switch,

just exposed wires to complete the circuit.

This isn’t a solution that will produce IP, and yet it’s a prominent

source of lighting in rural Rwanda, which makes up nearly 95 percent of

the country’s population. It’s a great example of how creative

individuals within the local context have ‘MacGyvered’ solutions to

their needs.

Between 70-95 percent of the creative economy’s economic output in

Africa comes from SMEs, the informal sector. They are local craftsman,

operating under the radar, using their creative wits to survive. They

are among the most resilient people on the planet.

In my previous career I was a product design consultant in Silicon

Valley—the land of abundance. I worked on new technologies for American

households, all for companies who wanted to build reputations for

innovation. The irony is that I see more innovation, and less

volatility, coming from what we call “the developing world” or the

informal sector, where innovation is born every day from extreme

constraints and necessity. (Just like in MacGyver).

In these places, the landscape is littered with broad meaty

challenges like the lack of energy access, cross-cultural barriers, and

the digital divide. They’re addressing these challenges in new ways and

new models that are poised to leapfrog anything we can imagine in

Silicon Valley. And I’m not alone in my thinking. This week at the World

Economic Forum 2013 Annual Meeting in Davos, Muhtar Kent, the CEO of

Coca-Cola, shared that Coke’s innovation, which he referred to as

“frugal innovation” is coming from emerging markets.

With that in mind, how might business leaders leverage the global

creative economy to enable the MacGyvers working within their company

and perhaps to support economic development in new economies? If you

can’t answer the question, you might find yourself struggling to catch

up sooner than you think.

Our top ten must-reads of 2012

We culled our twitter feed and

picked out the best of the best from 2012. Read on for links to new

tools, resources, and thought pieces on design and social

entrepreneurship.

DESIGN + SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP PIECES

1. Fast Company asks: “Do Designers Exploit the Poor While Trying to Do Good?” http://bit.ly/zKuQzT

2. Niti Bahn identifies what is missing in designing for the next billion: http://bit.ly/KAAAh0 (tools, methods, frameworks)

3. D-Rev’s Krista Donaldson discusses how to create products for people living on less than $4 per day: http://bit.ly/OoWlSY

BONUS READ! Harvard Business Review post on “The Smart Way to Make Profits While Serving the Poor” http://blogs.hbr.org/cs/2012/06/the_smart_way_to_make_profits.html

TOOLS

4. For empathy, check out “Life Without Lights,” a documentary photography project on energy poverty - http://lifewithoutlights.com/

5. For teaching, check out “Wicked Problems: problems worth

solving,” a handbook for teaching, learning, & doing disruptive

design work - http://bit.ly/zP1NpB

6. For doing, check out this new site providing free recs for

proven, low-cost household water treatment tech based on community need

- http://communitychoicestool.org/

7. For researching, check out this list of 46 smartphone apps for conducting ethnographic research - http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/apps.html

BONUS READ! For empathy, check out GSMA’s new report that gives a

glimpse into the lives of women living on less than $750/year - http://bit.ly/PMbil9

DEVELOPMENT THOUGHT PIECES

8. Esther Duflo & Co reveal their (controversial) research on

cookstoves: “Clean Cookstoves Must Be Rethought so They Actually Get

Used in Developing World” http://on.natgeo.com/OFQVIw

9. Stanford Social Innovation Review takes a cue from Esther Duflo

and posts a piece on the tricky claims social enterprise and non-profits

make when advocating for their work: http://bit.ly/PyNQsj

10. One of our most retweeted posts comes from The Guardian. Hugo

Slim posts his thoughts on: “The trouble with aid? Why helping people

is always complicated” http://gu.com/p/3cef2

Catapult, Davos bound!

We’re heading to the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2013 in

Davos, Switzerland this January 2013. Not only that, we’re joining:

Jeanne Bourgault, President, Internews

Theaster Gates, Director, Arts and Public Life Initiative, The University of Chicago

Caroline Watson, Director and Founder, Hua Dan

Paola Antonelli, Senior Curator, Department of Architecture and Design, Museum of Modern Art New York

for a session on Friday, January 25th exploring societal adversity

and creativity. We will also participate in a private session on the

“Creative Economy” where we’ll talk about building social-benefit design

programs.

Do we really need to say how psyched we are? Expect a blog on a

designers perspective of World Economic Forum and “improving the state

of the world.”

Creating Iconic Design Tools with the Noun Project

Ever needed an obscure icon for your

infographic? Need to make a universally understandable sign? Only have

20minutes to contextualize your product visualisation with a simple

picture? Do you dig Pictionary? Or are you sick of battling with

watermarks or creating amorphous stick figure monster icons?

Check out The Noun Project,

an iconic phenomenon that is a platform for creating and sharing a

global symbolic language. Catapult Design has used their resources on

several occasions within our design work and we will go through two

clear examples in a sec’, but first a bit of background…

The Noun Project hosts a library of

ever growing and iterated icons on their site that anybody can access,

use, and contribute to. You still need to acknowledge their creators

through an easy process of attribution (check their ‘usage‘

page for details) but their ethos is ‘open’ and they are all about

capturing and continuing a symbolic conversation (pictorially of

course). They also host Iconathons all over the place (mostly in the USA

so far), group lock-in brainstorm icon hacking mash ups that are run by

The Noun Project members to output a new set of icons around a pressing

theme (they did some cool stuff after Sandy…check the iconathon.org

site for details & upcoming events). I am itching to get to one, as

much to meet the crowd as make some symbolic magic happen. The site

(and the events) are meant for an audience well beyond designers.

Ultimately The Noun Project is opening up icon creation, access, and use

to a much greater audience and encouraging a flexible pictorial

literacy.

![]()

![]()

Catapult Design first tapped The Noun

Project resources when making a research tool for a project

investigating water access and use in rural India. I needed to get an

understanding of symbolic literacy in Rajasthan villages. I etched a

series of icons onto interlocking wooden tiles (some of them gleaned

from The Noun Project) and intentionally left a lot of tiles blank. In

each village we visited in Rajasthan, I asked people to experiment with

the tiles in 3 ways: first, I asked people to identify what the icons

referred to; then I asked people to explain a story using the tiles;

finally, I asked them to draw some tiles of their own. The intention was

to experiment with ways of discovering symbolic literacy, as well as

use those findings to inform any instructions or guides we would have to

make relevant to our water project.

![]()

![]()

The next time around was much more topical. Literacy Bridge,

an organization empowering children and adults with tools for knowledge

sharing and literacy learning, contacted us to help them solve an issue

with their Talking Book

interface. The Talking Book is an audio computer that shares

locally-relevant knowledge and improves literacy in areas with limited

access to literature. Literacy Bridge interacts with communities in

Northern Ghana where there is no word for ‘arrow’ in their lexicon. They

needed to be able to instruct the user to press a button relative to a

spoken instruction. We experimented with a bunch of different icons and

shapes, some of them from The Noun Project site, some of them created by

us, and a few lifted from other sources. Thanks to the timezone

difference between California and Ghana, the feedback loop was quick.

While we slept Literacy Bridge would report back the responses they got

from the field, we would adapt the icons according to their suggestions,

and the next day they would be tested again. We worked our way through

icons that had issues working with the spoken instructions of the

device, icons that implied too much of a specific task (‘fish’ = food),

that had too much potential religious connotation (‘plus’ = cross), or

that even had too much local political association (‘umbrella’ &

‘rooster’ are local Ghanaian political party symbols). We are continuing

to help Literacy Bridge achieve an appropriate interface through their

piloting stage (they are testing Talking Books in the thousands!).

image courtesy of Literacy Bridge

We plan to continue developing new

research games and other design resources, and to continue using The

Noun Project to help us when we need the right icon. It’s an excellent

resource even if I still cant find an icon for ‘design’ up there (nor an

icon for ‘icon’) but I’m hitting my sketchpad to work on it. I’m also

gonna get in touch with The Noun Project and suggest an iconathon themed

around rural life (on all continents)….oh and maybe I can put in a

festive wish for a ‘silhouette bank’ as well….?

Thanks Noun Project! Keep up the good work! We will see you at the next Iconathon!

——————–

And here is thanks and attribution to all of The Noun Project icon creators that unknowingly helped us out!

Pavel Pavlov: Thumbs Up/Approve

Stephen James Kennedy: Auto Rickshaw

Roger Cook & Don Shanosky: Baby, Train, Person , Ground Transport

Nick Levesque: Cooking Pan

Connor Cesa: Water Drop

Mike Endale: Hut, Community

Udaya Kumar: Rupee

Adrijan Karavdic: Elephant

Gibran Bisio: Paint Can

Edward Boatman, Saul Tannenbaum, Stephen Kennedy, Nikki Snow & Brooke Hamilton: Childrens Library

Valentina Piccione: Tree

Tak Imoto: Leaves

Michal Stassel: Axe

Jeremy Linden: Knifes

Kyle Scott, Roman J. Sokolov: Glasses

Listed as Unknown on NP: Maize, Apples, Camel, Bird, Pencil,

Umbrella, Flip-Flops, Bell, Speakers, Fuel Pump, Fish, Campfire, Tap,

Battery, Bicycle, Drinking Water, Hammer, Spanner/Wrench, Flame.

WE

WE

Tyler, Heather and Matt McLean featured on

Tyler, Heather and Matt McLean featured on

Nyange

Nyange

The focus of

The focus of

San

San We’re honored to have our CEO and Co-Founder, Heather Fleming, featured in PBS and Aol’s

We’re honored to have our CEO and Co-Founder, Heather Fleming, featured in PBS and Aol’s  Check

Check The Navajo Times, the premier newspaper on the Navajo Nation, covers Catapult Design in a story titled, “

The Navajo Times, the premier newspaper on the Navajo Nation, covers Catapult Design in a story titled, “

In “

In “ Read Catapult’s contribution to the Singapore Sessions’s “

Read Catapult’s contribution to the Singapore Sessions’s “ ELLE Magazine’s May 2010 issue features 2010

ELLE Magazine’s May 2010 issue features 2010  Catapult’s Heather Fleming, Mark Summer of

Catapult’s Heather Fleming, Mark Summer of  Teju Ravilochan of the

Teju Ravilochan of the  GOOD

GOOD PRI’s The World interviews Catapult CEO Heather Fleming for their feature on

PRI’s The World interviews Catapult CEO Heather Fleming for their feature on