https://youtu.be/0S73AJiFJZI Digha Nikaya The Tipitaka (Pali ti, “three,” + pitaka, “baskets”), or Pali canon, The Pali canon is a vast body of literature: in English translation The three divisions of the Tipitaka are: Vinaya Pitaka Where can I find a copy of the complete Pali canon (Tipitaka)? (Frequently Asked Question) https://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/dn/index.html Silakkhandha-vagga — The Division Concerning Morality (13 suttas) A selected anthology of 12 suttas from the Digha Nikaya, Handful of The translator appears in the square brackets []. The braces {} DN 1: Brahmajāla Sutta — The All-embracing Net of Views {D i 1} Jai Bheem Sukhihothu, visited What Boonyawad Forest Monastery, Thailand, Namo Buddhaya. Who is Buddha?

The Long Discourses

© 2005

is the collection of primary Pali language texts which form the

doctrinal foundation of Theravada Buddhism. The Tipitaka and the

paracanonical Pali texts (commentaries, chronicles, etc.) together

constitute the complete body of classical Theravada texts.

the texts add up to thousands of printed pages. Most (but not all) of

the Canon has already been published in English over the years. Although

only a small fraction of these texts are available on this website,

this collection can be a good place to start.

The collection of texts concerning the rules of conduct governing the

daily affairs within the Sangha — the community of bhikkhus (ordained

monks) and bhikkhunis (ordained nuns). Far more than merely a list of

rules, the Vinaya Pitaka also includes the stories behind the origin of

each rule, providing a detailed account of the Buddha’s solution to the

question of how to maintain communal harmony within a large and diverse

spiritual community.

Sutta Pitaka

The collection of suttas, or discourses, attributed to the Buddha and a

few of his closest disciples, containing all the central teachings of

Theravada Buddhism. (More than one thousand sutta translations are

available on this website.) The suttas are divided among five nikayas

(collections):

Digha Nikaya — the “long collection”

Majjhima Nikaya — the “middle-length collection”

Samyutta Nikaya — the “grouped collection”

Anguttara Nikaya — the “further-factored collection”

Khuddaka Nikaya — the “collection of little texts”:

Khuddakapatha

Dhammapada

Udana

Itivuttaka

Sutta Nipata

Vimanavatthu

Petavatthu

Theragatha

Therigatha

Jātaka

Niddesa

Patisambhidamagga

Apadana

Buddhavamsa

Cariyapitaka

Nettippakarana (included only in the Burmese edition of the Tipitaka)

Petakopadesa ( ” ” )

Milindapañha ( ” ” )

Abhidhamma Pitaka

The collection of texts in which the underlying doctrinal principles

presented in the Sutta Pitaka are reworked and reorganized into a

systematic framework that can be applied to an investigation into the

nature of mind and matter.

For further reading

Beyond the Tipitaka: A Field Guide to Post-canonical Pali Literature

Pali Language Study Aids offers links that may be useful to Pali students of every level.

Handbook of Pali Literature, by Somapala Jayawardhana (Colombo:

Karunaratne & Sons, Ltd., 1994). A guide, in dictionary form,

through the Pali canon, with detailed descriptions of the major

landmarks in the Canon.

An Analysis of the Pali Canon, Russell Webb, ed. (Kandy: Buddhist

Publication Society, 1975). An indispensable “roadmap” and outline of

the Pali canon. Contains an excellent index listing suttas by name.

Guide to Tipitaka, U Ko Lay, ed. (Delhi: Sri Satguru Publications,

1990). Another excellent outline of the Tipitaka, containing summaries

of many important suttas.

Buddhist Dictionary, by Nyanatiloka Mahathera (Kandy: Buddhist

Publication Society, 1980). A classic handbook of important terms and

concepts in Theravada Buddhism.

Digha Nikaya

The Long Discourses

© 2005

The Digha Nikaya, or “Collection of Long Discourses” (Pali digha =

“long”) is the first division of the Sutta Pitaka, and consists of

thirty-four suttas, grouped into three vaggas, or divisions:

Maha-vagga — The Large Division (10 suttas)

Patika-vagga — The Patika Division (11 suttas)

For a complete translation, see Maurice Walshe’s The Long Discourses of

the Buddha: A Translation of the Digha Nikaya (formerly titled: Thus

Have I Heard) (Boston: Wisdom Publications, 1987).

Leaves, Volume One, by Thanissaro Bhikkhu, is distributed free of charge

by Metta Forest Monastery. It is also available to read online and in

various ebook formats at dhammatalks.org

contain the volume and starting page number in the PTS romanized Pali

edition.

[Bodhi | Thanissaro]. In this important sutta, the first in the

Tipitaka, the Buddha describes sixty-two philosophical and speculative

views concerning the self and the world that were prevalent among

spiritual seekers of his day. In rejecting these teachings — many of

which thrive to this day — he decisively establishes the parameters of

his own.

DN 2: Samaññaphala Sutta — The Fruits of the Contemplative Life {D i 47}

[Thanissaro]. King Ajatasattu asks the Buddha, “What are the fruits of

the contemplative life, visible in the here and now?” The Buddha replies

by painting a comprehensive portrait of the Buddhist path of training,

illustrating each stage of the training with vivid similes.

DN 9: Potthapada Sutta — About Potthapada {D i 178} [Thanissaro]. The

wandering ascetic Potthapada brings to the Buddha a tangle of questions

concerning the nature of perception. The Buddha clears up the matter by

reviewing the fundamentals of concentration meditation and showing how

it can lead to the ultimate cessation of perception.

DN 11: Kevatta (Kevaddha) Sutta — To Kevatta {D i 211} [Thanissaro].

This discourse explores the role of miracles and conversations with

heavenly beings as a possible basis for faith and belief. The Buddha

does not deny the reality of such experiences, but he points out that —

of all possible miracles — the only reliable one is the miracle of

instruction in the proper training of the mind. As for heavenly beings,

they are subject to greed, anger, and delusion, and so the information

they give — especially with regard to the miracle of instruction — is

not necessarily trustworthy. Thus the only valid basis for faith is the

instruction that, when followed, brings about the end of one’s own

mental defilements. The tale that concludes the discourse is one of the

finest examples of the early Buddhist sense of humor. [TB]

DN 12: Lohicca Sutta — To Lohicca {D i 224} [Thanissaro]. A non-Buddhist

poses some good questions: If Dhamma is something that one must realize

for oneself, then what is the role of a teacher? Are there any teachers

who don’t deserve some sort of criticism? The Buddha’s reply includes a

sweeping summary of the entire path of practice.

DN 15: Maha-nidana Sutta — The Great Causes Discourse {D ii 55}

[Thanissaro]. One of the most profound discourses in the Pali canon,

which gives an extended treatment of the teachings of dependent

co-arising (paticca samuppada) and not-self (anatta) in an outlined

context of how these teachings function in practice. An explanatory

preface is included.

DN 16: Maha-parinibbana Sutta — Last Days of the Buddha/The Great

Discourse on the Total Unbinding {D ii 137; chapters 5-6} [Vajira/Story |

Thanissaro]. This wide-ranging sutta, the longest one in the Pali

canon, describes the events leading up to, during, and immediately

following the death and final release (parinibbana) of the Buddha. This

colorful narrative contains a wealth of Dhamma teachings, including the

Buddha’s final instructions that defined how Buddhism would be lived and

practiced long after the Buddha’s death — even to this day. But this

sutta also depicts, in simple language, the poignant human drama that

unfolds among the Buddha’s many devoted followers around the time of the

death of their beloved teacher.

DN 20: Maha-samaya Sutta — The Great Assembly/The Great Meeting {D ii

253} [Piyadassi | Thanissaro]. A large group of devas pays a visit to

the Buddha. This sutta is the closest thing in the Pali canon to a

“Who’s Who” of the deva worlds, providing useful material for anyone

interested in the cosmology of early Buddhism.

DN 21: Sakka-pañha Sutta — Sakka’s Questions {D ii 276; chapter 2}

[Thanissaro (excerpt)]. Sakka, the deva-king, asks the Buddha about the

sources of conflict, and about the path of practice that can bring it to

an end. This discourse ends with a humorous account about Sakka’s

frustration in trying to learn the Dhamma from other contemplatives.

It’s hard to find a teacher when you’re a king.

DN 22: Maha-satipatthana Sutta — The Great Establishing of Mindfulness

Discourse {D ii 290} [Burma Piṭaka Assn. | Thanissaro]. This sutta sets

out the full formula for the practice of establishing mindfulness, and

then gives an extensive account of one phrase in the formula: what it

means to remain focused on any of the four frames of reference—body,

feelings, mind, and mental qualities—in and of itself. [The text of this

sutta is identical to that of the Satipatthana Sutta (MN 10), except

that the Majjhima version omits the exposition of the Four Noble Truths

(sections 5a,b,c and d in part D of this version).] [TB]

DN 26: Cakkavatti Sutta — The Wheel-turning Emperor {D iii 58}

[Thanissaro (excerpt)]. In this excerpt the Buddha explains how skillful

action can result in the best kind of long life, the best kind of

beauty, the best kind of happiness, and the best kind of strength.

DN 29: Pāsādika Sutta — The Inspiring Discourse {D iii 117}

[Thanissaro]. Toward the end of his life, the Buddha describes his

accomplishment in establishing, through the Dhamma and Vinaya, a

complete holy life that will endure after his passing. Listing some of

the criticisms that might be leveled against him and his Dhamma-Vinaya,

he shows how those criticisms should be refuted. [TB]

DN 31: Sigalovada Sutta — The Buddha’s Advice to Sigalaka/The Discourse

to Sigala {D iii 180} [Kelly/Sawyer/Yareham | Narada]. The householder’s

code of discipline, as described by the Buddha to the layman Sigala.

This sutta offers valuable practical advice for householders on how to

conduct themselves skillfully in their relationships with parents,

spouses, children, pupils, teachers, employers, employees, friends, and

spiritual mentors so as to bring happiness to all concerned.

DN 32: Atanatiya Sutta — Discourse on Atanatiya {D iii 194} [Piyadassi].

One of the “protective verses” (paritta) that are chanted to this day

for ceremonial purposes by Theravada monks and nuns around the world.

See Piyadassi Thera’s The Book of Protection.

The Buddha grew up a prince in India. Until he was a young man, h e had

never encountered aging or death. When he happened to hear astory of a

servant’s death, he became very disillusioned about his posh life.

Leaving the palace and his princely lifestyle, he beganhis historic

journey towards enlighten…

Buddha means the Fully Enlightened One. He became the Buddha through the

realisation of the intrinsic / true nature of all things in the

universe, including existence / mind & body / life.

is the teaching of Siddhartha Gautama (Buddha) about the truth of life

and universe that reveals the concepts such as the Four Noble Truths,

Kamma. It is a whole school of teaching called dhamma which is much

older than the word “religion”.Buddhism is still a popular “religion”

nowadays, with millions of people all over the world who practice it.

The first step to becoming a Buddhist is understanding basic Buddhist

beliefs; this will help you decide if Buddhism is the religion for you.

Then, you can practice Buddhism and take part in centuries-old

traditions.

basic Buddhist terminology. This will make it much easier to understand

everything you will read, since many Buddhist terms can be very

unfamiliar, especially to Westerners. The basic terms of Buddhism

include but are not limited to:

Familiarize yourself with different Buddhist schools. The two most

popular Buddhist schools today are Theravada and Mahayana. Though these

two schools have the same basic beliefs, there are differences in the

teachings they focus on: Mahayana focuses heavily on becoming a

bodhisattva, Theravada focuses on practicing the dhamma, and so on.

Schools of Buddhism are far from being the same. There are

similarities to a degree but many schools of Buddhism have gone off on

tangents over time.

Because Buddhism is such an ancient religion, there are many

intricate differences between all the schools that cannot be covered in

detail here; spend time researching Buddhism to find out more.

about the life of Siddhartha Gautama. There are many books talking

about the founder of Buddhism, and a simple online search will reveal

many articles about his life as well. Siddhartha Gautama was a prince

who left his palace and lavish lifestyle to seek enlightenment. Though

he is not the only Buddha in existence, he is the historical founder of

Buddhism.

about the Four Noble Truths. One of the most foundational concepts of

Buddhism is summarized a teaching called the Four Noble Truths: the

truth of suffering, the truth of the cause of suffering, the truth of

the end of suffering, and the truth of the path that leads to the end of

suffering. In other words, suffering exists, it has a cause and an end,

and there is a way to bring about the end of suffering.

about Nibbana. Buddhists believe beings live multiple lives. Once a

being dies, they are born into a new life, and this cycle of living and

dying continues eternally. A being can be reborn in in a variety of

forms and conditions of life.

because karma determines where and when a being will be reborn. Kamma

consists of the good or bad actions of previous lifetimes and this

lifetime. Bad or good kamma may affect a being right away, thousands of

years from now, or in five lifetimes, depending on when the effects are

meant to occur.

Find a temple you feel comfortable joining. Many major cities have a

Buddhist temple, but each temple will stem from a different school (such

as Theravada or Zen), and each will certainly offer different services,

classes, and activities. The best way to learn about temples near you

is to visit them and talk to a Venerable or lay devotee.

a part of the community. Like most religions, Buddhism has a strong

sense of community, and the devotees and monks are welcoming and

informative. Begin attending classes and making friends at your temple.

Many Buddhist communities will travel together to different Buddhist

temples across the world. This is a fun way to get involved.

about taking refuge in the Triple Gem. The Triple Gem consists of the

Buddha, the Dhamma, and the Sangha. When you take refuge in the Triple

Gem, you will likely undergo a ceremony in which you vow to uphold the

Five Precepts, which are to not kill, not steal, not commit sexual

misconduct, refrain from false speech, and not consume intoxicants.

Do not feel obligated to take the Three Refuges, since upholding

Buddhist morality is the most important part of this religion.

If you cannot take the Three Refuges because of cultural reasons, or

if you cannot find a temple near you, you can still uphold the Five

Precepts.

connected to the Buddhist community. Attending classes at the temple

where you took refuge is a great way to stay connected to the Buddhist

community. A quick note upon visiting temples, don’t sit with the

bottoms of your feet towards altars, Buddha statues, or monks. Women may

not touch monks in any way, even to shake hands, and men cannot do the

same with nuns. A simple bow will do. Most temples offer lessons in

yoga, meditation, or various sutra lessons. Spend time with friends and

family members who are Buddhist, too.

Buddhism regularly. Many translated suttas are available online, your

temple might have a library, or you can buy suttas. There are also many

different Venerable monks and lay Buddhists who have written

explanations of Buddhist sutras. Some of the most popular Buddhist

sutras are: The Diamond Sutra, The Heart Sutra, and The Great Perfection

of Wisdom Sutra.

There are hundreds of Buddhist concepts and teachings to study, but

try not to feel overwhelmed or pressured to “get it” right away.

the Five Precepts. When you took refuge in the Triple Gem, you vowed to

uphold the Five Precepts, but this can be difficult at times. Do your

best to not kill any living creature, be honest, not consume

intoxicants, do not steal, and do not commit sexual misconduct. If you

break the precepts, simply repent, and do your best to keep upholding

them.

Practice the Middle Way. This is an important part of Buddhism which requires Buddhists to lead a

balanced life that is not too lavish or too stringent. The Middle Way

is also known as the “Noble Eightfold Path,” which teaches Buddhists to

abide by eight elements. Spend time studying all eight:

- Right view

- Right intention

- Right speech

- Right action

- Right livelihood

- Right effort

- Right mindfulness

- Right concentration

Theravāda Buddhism, the Bodhisatta concept (Pāli: Bodhisatta,

Sanskrit:Bodhisattva) is considered to be seeking awakenment so that,

once awakened,one can efficiently aid other beings to develop an insight

to know things as truly asthey are.

Buddha’s previous life experiences as a Bodhisatta before Buddhahood

are recorded in the texts of the Jataka. Lay Buddhists of Theravāda

tradition often seek inspiration in his skills as a good layman from

these texts, which not only account his historical life, but also many

other previous lives.

is a being who aspires for Bodhi or Awakenment. The concept of

Bodhisatta (meaning Buddha-to-be) is one of the most important concepts

in Buddhism. Etymologically the term can be separated into two parts,

be’, means ‘a being’ or ‘one who is’ or ‘a sentient being.’ Hence, the

term is taken to mean ‘one whose essence is Awakenment’ or ‘awakened

knowledge’. By implication it means a seeker of the awakenment and a

Buddha-to-be. There is also a suggestion that the Pāli term may be

derived from

who is attached to or desires to gain awakenment.’ In original Pāli

texts of early Buddhism, the term Bodhisatta was used more exclusivelyto

designate Gotama Buddha prior to his enlightenment.

The concept of Bodhisatta, along with that of Buddha and of the

cakravartin (world-ruler), was in vogue in India even before the

appearance of Gotama Buddha. When Prince Siddhattha (who later became

Gotama Buddha) took conception in the womb of Queen Maya, a seer

predicted that this son would become either a world-ruler( cakravartin)

or a Buddha. While answering a question by a Brahmin, Gotama Buddha

himself once admitted that he was not a god, but a Buddha. This

impliesthat he indirectly meant that he was one in the lineage of

buddhas.

This proves that it contains the teachings of not just asingle Buddha,

but of all the Buddhas. The Amagandha Sutta is similarly recorded asa

discourse not of Gotama Buddha but of a past Buddha named Kassapa.

Perfect Awaktenment is an impersonal universal phenomenon occurring at a

particular context both in time and space. So, the Buddha is a person

who re-discovers the Dhamma, which had become lost to the world. Gotama

Buddha himself, as well as others, used the term Bodhisatta to indicate

his careerfrom the time of his renunciation up to the time of his

awakenment. During thelater period, use of this term “Bodhisatta” was

extended to denote the period from

Bodhisatta referring to the state before the attainment of Awakenment

in the life of Gotama Buddha. Here, the Bodhisatta is depicted as the

One seeking higher knowledge.

Bodhisatta as a generic term referring to the previous existence of any

Buddha in the past. This theory is based on the acceptance on plurality

of the buddhas.In the Khuddaka Nikāya, the word “Bodhisatta” does not

occur as often as in the other four Nikāyas, but there is further

development of this concept found here. Theold stratum of Khuddaka

Nikāya includes the last two chapers of Suttanipāta while the new

stratum includes texts like Buddhavaṃsa, Cariyāpiṭaka and Apadāna.

Suttanipāta refers to Gotama Bodhisatta as a being who was born in

thisworld for happiness and wheal of the people (hitasukhatāya). This

idea of acompassionate Bodhisatta is also expressed in the Canon.

In the Buddhavaṃsa, the Bodhisatta ideal is developed to the

greatestextent. The Buddhavaṃsa is entirely based on the history of

Gotama Buddha’s career as the Bodhisatta from the time of making his

abhinīhāra(resolve) before Dīpańkara Buddha to become a Buddha in the

future. Undereach and every past Buddha, Gotama Bodhisatta receives a

declaration(vyākaraṇa) that he would be the Buddha named Gotama in

distant future.Here, the term “Bodhisatta” refers to an ideal person,

who makes a vow tobecome a fully and completely enlightened Buddha

(sammāsambuddha) outof compassion for all sentient beings. He performs

various acts of merit and finally receives a prophecy of his future

Buddhahood. In addition, he had also made a vow to become a Bodhisatta

only after the attainment of arahantship. This is portrayed in the

chronicle of Sumedha, where he waslying in the mud and offering his body

to the Dīpańkara Buddha to walk on.

to the Buddhavaṃsa and Cariyāpiṭaka, there are eight

conditions(aṭṭhadhammā) which are mentioned as the preconditions for

anyone to become aBodhisatta and ten preconditions (pāramī) are to be

practiced and fulfilled tobecome a Buddha. In this aspect, the Jātaka

stories might be a later fabrication inan attempt to connect the mode of

fulfillment of pāramīs with the varied forms of existences of the

Gotama Bodhisatta. The generalization of preliminaries leading to

Buddhahood was thus introduced for the first time in Pāli tradition and

it furtherdeveloped in the Aṭṭhakathā literature.

expanded use of the term “Bodhisatta” is explicitly expressed in the

Khuddakapātha. In the eighth chapter of this canonical text

(theNidhikandasutta), the goal of Buddhahood is presented as a goal that

shouldbe pursued by certain exceptional beings. The sutta mentions a

type of treasure that is more permanent and which follows beings from

birth to birth. This treasure results from giving (dāna), morality

(sīla), abstinence (samyama),and observing restraint (dama). This

treasure fulfills all desires, leads to arebirth in a beautiful body and

leads to rebirth in the human realm from whichliberation is possible.

Moreover, the qualities of charity, virtue, abstinence andrestraint

would lead to the wisdom which produces the “bliss of Extinguishment” of

Arahants or pratyekabuddhas or completely awakened buddhas.

The Udāna also mentions the word “Bodhisatta” at one place, but it is

withreference to the mothers of Bodhisattas. It predicts that mothers of

all Bodhisattas would die within seven days after their birth. It is

the Dhammatā (general nature)that certain things are predetermined for a

Bodhisatta these are his parents, Bodhitree, chief disciples

(aggasāvakā), son and attendant (upaṭṭhāka).

was a commentator who showed greater interest in the disseminationof

the Bodhisatta doctrine and introduce new concepts in the Theravāda

tradition. Through the Buddhavaṃsa and Cariyāpiṭaka contain certain

ingredients that can beregarded as the precursors of later developments

in the commentaries, but theBodhisatta concept gained acceleration and

diversification in the Theravādatradition in the form of Aṭṭhakathā

literature.

The word “bodhi” is a nominative derivative of the root “budh” (meaning

to be awake, awakened etc.) and it means awakenment or supreme

knowledge. Thecanonical texts give its meanings as the realization of

the Four Noble truths (arya-saccāni) and the Seven Factors of Awakenment

(bojjhaṅga). In the Aṭṭhakathātexts, a classic definition of the verbal

form “bujjhati”, meaning awake orenlightened or the one who knows, is

given in Atthasālini and Sammohavinodanī.

might be argued that these Bodhisatta kings were influenced by the

Mahāyāna doctrines when they adopted certain qualities of the Bodhisatta

or took the Bodhisatta vow. But this does not dismiss the fact that the

Bodhisatta ideal wastaken seriously by Theravādin kings. The Bodhisatta

ideal obtained a prominentplace in Theravāda Buddhist theory and

practice. A king might be influenced by Mahāyāna ideas at a given point

of time. But this does not mean that certain Theravāda doctrines,

including the ideas of a Bodhisatta as found in theBuddhavaṃsa and

Cariyāpiṭaka, were not equally influential.

The presence of a Bodhisatta ideal in Theravāda Buddhism is

alsorepresented by the numerous examples of other Theravādins who have

either referred to themselves or have been referred by others as

Bodhisattas. Thecelebrated commentator Buddhaghosa was viewed by the

monks of the Anuraadhapura monastery as being an incarnation of Metteya.

There are also someinstances of Theravādin monks who expressed their

desire to become fully awakened buddhas. After being deemed worthy of

receiving certain secretteachings by his meditation teacher, bhikkhu

Doratiyaaveye of Sri Lanka (ca. 1900),refused to practice such

techniques. He felt that it would pose hindrance in his pathto attain

the level of arahant in this lifetime or within seven lives. He saw

himself asa Bodhisatta who had already made a vow to attain Buddhahood

in the future.

The vow to become a Buddha was also taken by certain Theravādin textual

copyistsand authors. The author of the commentary on the Jātaka (the

Jātakāṭṭhakathā)concludes his work with the vow to complete the ten

Bodhisatta perfections inthe future so that he will become a Buddha and

liberate the whole world with its gods from the bondage of repeated

births and guide them to the most excellentand tranquil Nibbāna.

Another example of a Theravādin author who wished tobecome a Buddha by

following the Bodhisatta-yāna is the `Sri Lankan monkMahā-Tipitaka

Cūlābhaya. In his subcommentary on the “Questions of King Milinda”during

the twelfth-century, he wrote that he wished to become a Buddha at the

endof his work.

Prince Siddhattha attained Awakenment and transformed himself into a

Buddha from Bodhisatta, he did so as a human being and lived and passed

away as such. He himself admitted that he was a Buddha and not a

supernatural being. He was only the discoverer of a lost teaching. His

greatness was that he found out whath is contemporaries could not

discover at all or only discovered partially. Both intellectually and

morally he was a great man (mahapurisa) and a historical personality.

However, when we analyze the term “Bodhisatta” in Theravāda Buddhism, it

not only refers to Gotama and all previous buddhas before their

aakenment, but it also applies to any being who wishes to pursue the

path to perfect Buddhahood.

Though the Theravādins believe that anyone can become a Bodhisatta,

they do not stipulate or insist that everyone must become a Bodhisatta

as this is not considered to be reasonable. It is up to the individual

to decide which path to take, that of the Srāvaka, that of the

Pratyekabuddha, or that of the Samyaksambuddha [i.e., sammāsambuddha].

This concept resulted in a moregeneral adherence to the ideal by

numerous Theravādin kings, monks, scholars andeven common people.

The introduction of three kinds of Bodhisatta namely Mahā-Bodhisatta,

Pacceka-Bodhisatta and Sāvaka-Bodhisatta by Dhammapāla is a new

departure in the Theravāda doctrine and the Bodhisatta ideal became

reserved for only certainexceptional people. Thus, when the path of

Buddhahood was made more difficultduring the process of exalting the

buddhas, the Thravādins had to emphasize theimportance of the following

sāvaka-bodhi more than before as the alternative andeasier way to

emancipation. Though the glorification of buddhas bears the

The Bodhisatta-yāna and the goal of Buddhahood were already accepted

as one of three possible goals by followers of Theravāda Buddhism.

However, this same goalwas viewed as the only acceptable goal by the

followers of Mahāyāna Buddhism.Hence, it should be stressed that the

change introduced by the Mahāyāna traditionswas not an invention of a

new ideology or any innovative thinking, but it was ratherthe adoption

of an already accepted exceptional ideal and bringing it into

prominence.

Bodhisattva ideals

The bodhisattva ideal

The teachings of Buddhism are about your life, about being the person

you are. The practices of Buddhism are about being willing to be

intimate with yourself, with your idiosyncrasies. So when we talk about

compassion and the ideal of the bodhisattva, we are talking about how we

as ordinary people—with this body, this mind, this life, these

problems—can find generosity, effort, and wisdom right here and now. We

realize that they are always available.

Bodhisattvas are beings who are dedicated to the universal

awakening, or enlightenment, of everyone. They exist as guides and

providers of relief to suffering beings. We will be learning about the

lives of some bodhisattvas who are well known in the Buddhist tradition.

They are models who exemplify lives dedicated to eradicating suffering

in the world. But as we go along, it is important to remember that as

soon as you are struck with the urge or intention to take on such a

bodhisattva practice, you are included in the ranks of the bodhisattvas.

Bodhisattvas can be awesome in their power, radiance, and wisdom, and

they can be as ordinary as your next-door neighbor. Bodhisattvas appear

wherever they can be most helpful.

A buddha, or awakened one, is a being who has fully realized

liberation from the suffering of delusions and conditioning. This

awakening is realized through deep experiential awareness of the

undefiled nature of all beings and all phenomena, which are seen to be

essentially pristine and clear. Buddhas see that everything is all

right, just as it is. This insight in some sense liberates all beings,

who may not yet realize this truth of openness and freedom themselves

because of their own confusion.

A bodhisattva is a being who carries out the work of the buddhas,

vowing not to personally settle into the salvation of final buddhahood

until she or he can assist all beings throughout the vast reaches of

time and space to fully be free. A bodhisattva is a buddha with her

sleeves rolled up.

On the bodhisattva path, we follow teachings about generosity,

patience, ethical conduct, meditative balance, and insight into what is

essential, so we can come to live in a way that benefits others. At the

same time, we learn compassion for ourselves and see that we are not

separate from the people we have imagined are estranged from us. Self

and other heal together.

The bodhisattva is the ideal of Mahayana (Great Vehicle) Buddhism,

the dominant branch of Buddhism in North Asia: Tibet, China, Mongolia,

Taiwan, Korea, and Japan, as well as Vietnam in Southeast Asia. This

tradition is now spreading and being adapted to Western cultures. The

word bodhisattva comes from the Sanskrit roots bodhi, meaning

“awakening” or “enlightenment,” and sattva, meaning “sentient being.”

Bodhisattvas are radiant beings who exist in innumerable forms,

functioning in helpful ways right in the middle of the busyness of the

world.

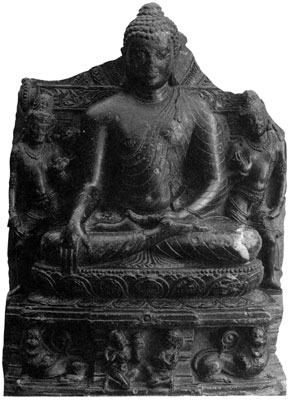

and attendant bodhisattvas, Bodh-gaya, tenth century. Courtesy of The

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1920 (20.58.16).

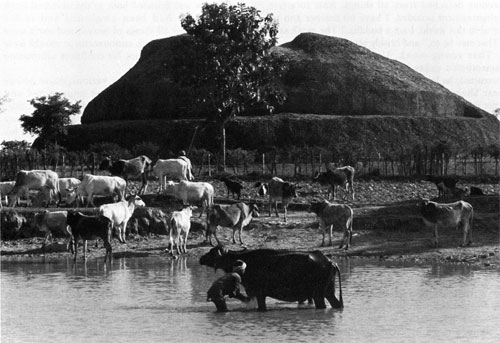

This episode of the life of Shakyamuni Buddha, as retold by Nikkyo Niwano, starts in Bodh-gaya

following the Buddha’s awakenment under the Bodhi tree. The decision

to turn the dhamma wheel initiates a teaching mission that lasted over

forty years and took the Great Sage back and forth across the breadth of

northern India.

Concerning his meditation after awakenment and his decision to teach, in “Tactfulness” the Buddha himself says,

[I] again reflected thus:

‘Having come forth into the disturbed and evil world,

I, according to the buddhas’ behest,

Will also obediently proceed.’

Having finished pondering this matter,

I instantly went to Varanasi.

Here the Buddha is saying, “I came forth into this disturbed and evil

world charged with the mission of saving it.” Buddhists always remember

the Buddha’s resoluteness and great compassion for all living beings,

which must be regarded not merely as expressions of the Buddha’s

personal concern for us but as the real concerns of all humankind. Even

if we feel that we are as yet very far from achieving the spiritual

development of the Buddha, we must strive to accomplish the mission

entrusted to us as ordinary people.

Undoubtedly, during the several weeks that he remained at Bodh-gaya

in meditation and thought following his awakenment, the Buddha

devoted much time to organizing the teachings he would present in

explaining the profound truth to which he had been awakened. When he

at last felt fully prepared, the Buddha departed on the teaching mission

that would bring his message to others.

On beginning his mission Shakyamuni thought, “To whom should I first

preach this Law? Who will be able to understand it?” His former

teachers, Arada-Kalama and Udraka-Ramaputra, came to mind; but he

learned that the two hermit-sages were already dead. He then remembered

the five ascetics who had practiced austerities with him and later,

becoming disillusioned, had left him. He was told that they were staying

at Deer Park, near Varanasi, where many hermits gathered for ascetic

practices. Alone, Shakyamuni made his way on foot to Varanasi, over two

hundred kilometers to the west of Bodh-gaya.

Shortly after leaving Bodh-gaya, Shakyamuni encountered a young monk

who addressed him, saying, “You look purified. Under whom have you

studied in becoming a monk? To what kind of teaching have you devoted

yourself?” Shakyamuni replied with quiet dignity, “I am all-wise, a

victor over all things. I have extinguished all desires and become

detached from all things. Able to attain awakenment unaided, I have

no teacher and no equal in this world. I am a buddha.” The monk said,

“That may be so,” and briskly resumed his course.

That young monk, Upaka by name, is still remembered today because, by

not asking to be instructed, he lost the opportunity to be the first to

hear Shakyamuni’s message. Anyone who seeks after the Way must regard

all people with whom he comes into contact as teachers and all places as

proper places in which to learn the truth. For example, the Flower

Garland Sutta contains the story of a monk called

Sudhana-shreshthidaraka, who was able to learn a valuable lesson from a

prostitute. Thus Upaka, who was immediately moved by the serene dignity

of the Buddha, ought to have respectfully asked Shakyamuni to explain

his awakenment. Upaka was later to regret sorely that he had not done

so, and he did eventually accept the teachings of the Buddha.

After walking many days across the hot plains of

India, Shakyamuni finally reached Varanasi. He soon went to Deer Park,

where the five ascetics who had accompanied him for six years were then

staying.

Seeing a monk approaching, the five recognized him as the Gautama

whom they had followed in his practice of austerities (Gautama was

Shakyamuni’s family name). “That is Gautama, isn’t it? He is the fallen

monk who failed in his ascetic practices. Let us refrain from paying our

respects to him when he comes to us. However, we may give him some

food…”

Though they spoke thus to one another, when they met Shakyamuni they

were so effected by his dignity that they were incapable of remaining

indifferent. Each rose unconsciously and received him reverently, making

obeisance to him. They took his begging bowl, washed his feet and dried

them, and prepared a seat of honor for him. They greeted him: “Our

friend, Gautama!”

Shakyamuni then solemnly declared: “You must no longer address me as

Gautama, nor yet as friend. I have already become a buddha. I will

preach to you the eternal truth I have perceived. If you practice this

according to my teaching, you will surely attain enlightenment and

achieve your purpose in becoming monks.”

Anyone other than Shakyamuni making such a seemingly haughty

statement, so similar to his declaration to Upaka, would have inevitably

invited accusations of arrogance. It is not possible for the ordinary

human mind to encompass Shakyamuni’s own comprehension of his

buddhahood. His awareness was founded both in the universal truth to

which he had been awakened and in his realization that all things of

heaven and earth were his responsibility. His announcement would have

been astounding without his confident affirmation “I am a buddha.”

Those who linger at the various stages before attaining buddhahood

are yet unperfected and imprudent and therefore should always be modest.

However, since Shakyamuni was a buddha, any reticence on his part would

have denigrated his buddhahood. We must understand this point in order

to appreciate that Shakyamuni was speaking forthrightly, not exhibiting

overweening pride.

The five monks were inspired by Shakyamuni’s virtuous mien and paid

him homage despite their initial reaction, but they did not consent

immediately to listen to Shakyamuni’s teaching. In fact, at first they

did not want to hear it. However, Shakyamuni, ardently desiring to

enlighten them, addressed them three times, saying, “I will now preach

the Law to you. Come and listen to me.” Three times they refused to heed

him. Finally he said to them sternly, “Monks! Have I ever spoken

untruthfully to you? Have I?” They recalled that he had always taught

them with honesty, and they were moved by his compassionate wish to save

all sentient beings from their sufferings. As they reflected on these

things, a desire to hear Shakyamuni’s message gradually arose in them.

Shakyamuni had reached Deer Park in the afternoon, and he spent the

hours from early evening onward alone in silent meditation. At midnight,

when the sounds of the day had died away, a serene air stole upon the

surroundings and Shakyamuni at last began to preach his epochal sermon.

“Monks! In this world there are two extremes—that of

self-mortification and that of self-indulgence—that must be avoided. By

avoiding these two extremes and following the Middle Path, I have

attained the highest enlightenment.” Thus Shakyamuni began his first

sermon.

He then preached the Four Noble Truths, teaching that man must

recognize that life is filled with suffering (the Truth of Suffering),

grasp the real cause of suffering (the Truth of Cause), and by daily

religious practice (the Truth of the Path) extinguish all kinds of

suffering (the Truth of Extinction). Shakyamuni went on to expound the

Eightfold Path—right view, right thinking, right speech, right action,

right living, right endeavor, right memory, and right meditation—as the

Truth of the Path leading to the extinction of all suffering. First

Ajnata-Kaundinya and then each of the other bhikshus, or monks,

reached the first stage of enlightenment, becoming free of all

illusions. Speaking of this first sermon Shakyamuni says, in Chapter Two

of the Lotus Sutra,

The nirvana-nature of all existence,

Which is inexpressible,

I by [my] tactful ability

Preached to the five bhikshus.

This is called [the first] rolling of the Law-wheel,

Whereupon there was the news of nirvana

And also the separate names of Arhat,

Of Law, and of Sangha.

The expression “rolling of the Law-wheel” requires some explanation.

In Indian mythology the ideal ruler, known as a wheel-rolling king, was

supposed to govern by rolling a wheel and to rule not by armed might but

by virtue. In Buddhist terms there are four such kings, each with a

precious wheel of gold, silver, copper, or iron, in accordance with how

large a portion of the world he rules. The king of the gold wheel unites

and rules the entire world.

The Buddha’s Law is like the wheel of gold. When a great sage

preaches this Law it is as if he had rolled the gold wheel: all come to

respect and honor him and his rule, or teaching. Thus “to roll the

Law-wheel,” or the “wheel of the Law,” means to teach the Buddha’s Law.

During the forty-five years between his first sermon and his death,

Shakyamuni ceaselessly rolled the Law-wheel in the villages and

countries of northern and central India, and that Law-wheel continued to

roll even after his death. In one direction, it rolled through Central

Asia into China and Korea and on to Japan; in another direction, it

rolled throughout Southeast Asia.

Reprinted with permission from Shakyamuni Buddha: A Narrative Biography, by Nikkyo Niwano (Kosei: Tokyo, 1981), 46-59. (c) 1980 by Kosei Publishing Company.

what has been said so far about Budhahood in Buddha’s own words. Is it

possible to describe the Buddha as a god, an incarnation (avatara) or a

prophet, Messaiah of a god? If so why? If not why not ? Explain.

https://www.buddhanet.net/e-learning/snapshot01.htm

Buddhism - Major Differences From Other Religions

1. There is no almighty God in Buddhism. There is no one to hand out rewards or punishments on a supposedly Judgement Day.

2. Buddhism is strictly not a religion in the context of being a faith and worship owing allegiance to a supernatural being.

3. No saviour concept in Buddhism. A Buddha is not a saviour who saves

others by his personal salvation. Although a Buddhist seeks refuge in

the Buddha as his incomparable guide who indicates the path of purity,

he makes no servile surrender. A Buddhist does not think that he can

gain purity merely by seeking refuge in the Buddha or by mere faith in

Him. It is not within the power of a Buddha to wash away the impurities

of others

4. A Buddha is not an incarnation of a god/God (as

claimed by some Hindu followers). The relationship between a Buddha and

his disciples and followers is that of a teacher and student.

5.

The liberation of self is the responsibility of one’s own self. Buddhism

does not call for an unquestionable blind faith by all Buddhist

followers. It places heavy emphasis on self-reliance, self discipline

and individual striving.

6. Taking refuge in The Triple Gems i.e.

the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha; does not mean self-surrender or

total reliance on an external force or third party for help or

salvation.

7. Dharma (the teachings in Buddhism) exists

regardless whether there is a Buddha. Sakyamuni Buddha (as the

historical Buddha) discovered and shared the teachings/ universal truths

with all sentient beings. He is neither the creator of such teachings

nor the prophet of an almighty God to transmit such teachings to others.

8. Especially emphasized in Mahayana Buddhism, all sentient beings have

Buddha Nature/ Essence. One can become a Buddha (a supreme enlightened

being) in due course if one practises diligently and attains purity of

mind (ie absolutely no delusions or afflictions).

9. In Buddhism,

the ultimate objective of followers/practitioners is enlightenment

and/or liberation from Samsara; rather than to go to a Heaven (or a deva

realm in the context of Buddhist cosmology).

10. Karma and Karma

Force are cornerstones in Buddhist doctrines. They are expounded very

thoroughly in Buddhism. Karma refers to an important metaphysical

concept concerned with action and its consequences. This law of karma

explains the problem of sufferings, the mystery of the so-called fate

and predestination of some religions, and above all the apparent

inequality of mankind.

11. Rebirth is another key doctrine in

Buddhism and it goes hand in hand with karma. There is a subtle

difference between rebirth and reincarnation as expounded in Hinduism.

Buddhism rejects the theory of a transmigrating permanent soul, whether

created by a god or emanating from a divine essence.

12. Maitri

or Metta in Pali (Loving Kindness) and Karuna (Compassion) to all living

beings including animals. Buddhism strictly forbids animal sacrifice

for whatever reason. Vegetarianism is recommended but not compulsory.

13. The importance of Non-attachment. Buddhism goes beyond doing good

and being good. One must not be attached to good deeds or the idea of

doing good; otherwise it is just another form of craving.

14. In

Buddhism, there is consideration for all sentient beings (versus human

beings, as in other religions). Buddhists acknowledge/accept the

existence of animals and beings in other realms in Samsara.

15.

No holy war concept in Buddhism. Killing is breaking a key moral precept

in Buddhism. One is strictly forbidden to kill another person in the

name of religion, a religious leader or whatsoever religious pretext or

worldly excuse.

16. Suffering is another cornerstone in Buddhism.

It is the first of the Four Noble Truths. Sufferings are very well

analysed and explained in Buddhism.

17. The idea of sin or original sin has no place in Buddhism. Also, sin should not be equated to suffering.

18. Buddhist teachings expound no beginning and no end to one’s

existence or life. There is virtually no recognition of a first cause —

e.g. how does human existence first come about?

19. The Dharma

provides a very detailed explanation of the doctrine of anatman {anatta

in Pali} or soullessness , i.e. there is no soul entity (whether in one

life of many lives).

20. The Buddha is omniscient but he is not

omnipotent. He is capable of innumerable feats but there are three

things he cannot do. Also, a Buddha does not claim to be a creator of

lives or the Universe.

21. Prajna [Panna in Pali] or Transcendent

Wisdom occupies a paramount position in Buddhist teachings. Sakyamuni

Buddha expounded Prajna concepts for some 20 years of his ministry. One

is taught to balance compassion with prajna i.e.emotion (faith) with

rationale (right understanding / truth / logic).

22. The

tradition and practice of meditation in Buddhism are relatively

important and strong. While all religions teach some forms or variations

of stabilising/single-pointedness meditation, only Buddhism emphazises

Vipassana (Insight) meditation as a powerful tool to assist one in

seeking liberation/enlightenment.

23. The doctrine of Sunyata or

Emptiness is unique to Buddhism and its many aspects are well expounded

in advanced Buddhist teachings. Briefly, this doctrine asserts the

transcendental nature of Ultimate Reality. It declares the phenomenal

world to be void of all limitations of particularization and that all

concepts of dualism are abolished.

24. Conditioned Arising

[Paticcasamuppada in Pali] or Dependent Origination is another key

doctrine in Buddhism. This doctrine explains that all psychological and

physical phenomena constituting individual existence are interdependent

and mutually condition each other; this at the same time describes what

entangles sentient beings in samsara.

25. The concept of Hell(s)

in Buddhism is very different from that of other religions. It is not a

place for eternal damnation as viewed by ‘almighty creator’ religions.

In Buddhism, it is just one of the six realms in Samsara [i.e. the worst

of three undesirable realms]. Also, there are virtually unlimited

number of hells in the Buddhist cosmology as there are infinite number

of Buddha worlds.

26. The Buddhist cosmology (or universe) is

distinctly different from that of other religions which usually

recognise only this solar system (Earth) as the centre of the Universe

and the only planet with living beings. The Buddhist viewpoint of a

Buddha world (also known as Three Thousand-Fold World System) is that of

one billion solar systems. Besides, the Mahayana Buddhist doctrines

expound that there are other contemporary Buddha worlds like Amitabha’s

Pure Land and Bhaisajyaguru’s world system.

27. Samsara is a

fundamental concept in Buddhism and it is simply the ‘perpetual cycles

of existence’ or endless rounds of rebirth among the six realms of

existence. This cyclical rebirth pattern will only end when a sentient

being attains Nibbana, i.e. virtual exhaustion of kamma, habitual

traces, defilements and delusions. All other religions preach one

heaven, one earth and one hell, but this perspective is very limited

compared with Buddhist samsara where heaven is just one of the six

realms of existence and it has 28 levels/planes.