09/04/10

Filed under:

General

Posted by:

site admin @ 10:01 pm

| Loving kindness, peace and universal compassion |

| The Middle Path - avoiding extremes, emptiness |

| Blessings of practice - achievement, wisdom, virtue, fortune and dignity |

| Purity of Dharma - it leads to liberation, outside of time or space |

| The Buddha’s Teaching - wisdom |

05 09 2010 FREE ONLINE eNālandā Research and Practice UNIVERSITY JATAKA TALES

LESSON – 21

The secret of health for both mind and body is not to mourn for the past, worry about the future, or anticipate troubles, but to live in the present moment wisely and earnestly.

– Buddha

EDUCATE (BUDDHA)!MEDITATE (DHAMMA)!ORGANISE (SANGHA)!

WISDOM IS POWER

Awakened One Shows the Path to Attain Ultimate Bliss

Anyone Can Attain Ultimate Bliss Just Visit:

http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org

COMPUTER IS AN ENTERTAINMENT INSTRUMENT!

INTERNET!

IS

ENTERTAINMENT NET!

TO BE MOST APPROPRIATE!

Using such an instrument

The Free e-Nālandā Research and Practice University has been re-organized to function through the following Schools of Learning :

Buddha’s Sangha Practiced His Dhamma Free of cost, hence the Free- e-Nālandā Research and Practice University follows suit

As the Original Nālandā University did not offer any Degree, so also the Free e-Nālandā Research and Practice University.

AWAKEN-NESS

III.

IV.

V.

VI.

with

Level I: Introduction to Buddhism

Level II: Buddhist Studies

TO ATTAIN

Level III: Stream-Enterer

Level IV: Once - Returner

Level V: Non-Returner

Level VI: Arhat

Jambudvipa, i.e, PraBuddha Bharath scientific thought in

mathematics,

astronomy,

alchemy,

and

anatomy

Philosophy and Comparative Religions;

Historical Studies;

International Relations and Peace Studies;

Business Management in relation to Public Policy and Development Studies;

Languages and Literature;

and Ecology and Environmental Studies

Welcome to the Free Online e-Nālandā University-

Course Programs:

JATAKA TALES-PART II

Jataka Tales and Storytelling

|

“Jataka Tales and Storytelling” is a presentation at the Student Life Building, Northern Illinois University on 27 April 2001, sponsored by Center for Southeast Asian Studies, by Dr. Wajuppa Tossa, Prasong Saihong, and Phanida Phunkrathok.

THE PIOUS SON-IN-LAW1

Nai Dee was a rich farmer. His rice fields stretched in all directions. But Nai Dee did not approve of his new son-in-law, Thid Kham. Thid Kham was a very pious man. He had spent many years in the monkshood and still retained his pious nature. One day as the father-in-law and his new son-in-law were walking Nai Dee began to brag.

“Look at all of these fields! All of this is mine! The rice is just being planted now, but when the harvest comes, I will be a very rich man.”

Thid Kham looked over the rice field and spoke cautiously.

“Father-in-law this is not certain. The rice grows well now, but a flood might come and spoil the crop. Remember what the Lord Buddha has said,

“Dai dai nai lok luan anijang. Nothing is certain.”

The father-in-law did not like to hear this. He was angry but kept silent. Some weeks later the two walked again in the fields.

“See Thid Kham. There was no flood. The rice is blooming now. There is sure to be a good harvest!”

But Thid Kham still was cautious.

“This is not certain, father-in-law. Yes, the rice is blooming. But insects might come and eat the rice before it can be harvested. Remember what the Lord Buddha has said,

“Dai dai nai lok luan anijang. Nothing is certain.”

His father-in-law was furious to hear these words from his son-in-law. He waited until the rice was hanging heavy and ripe on its stalks. Then he walked with Thid Kham to the fields again.

“Now will you stop your foolish sayings. See, the rice is ripe. Floods did not come. Insects did not come. This is certain. I am a rich man.”

“I do not believe this is certain, father-in-law. I can see that the grain is ripe. But it is not harvested yet. Fire might sweep through the fields and burn it all. No, you must remember the words of the Lord Buddha,

“Dai dai nai lok luan anijang. Nothing is certain.”

The father-in-law could hardly keep his temper. As soon as the rice was harvested and stored in the granaries, he brought Thid Kham to see.

“Now LOOK. There was no flood, no insects, no fire. This is now a certain thing. You can see for yourself!”

But still Thid Kham hesitated.

“Yes, I can see the rice. But still mice may come and eat it. I must repeat the words of the Lord Buddha,

“Dai dai nai lok luan anijang. Nothing is certain!”

The father-in-law was furious. He ordered some of the rice cooked and brought Thid Kham to his house.

“Here Thid Kham. The rice grew, it bloomed, it ripened, it was harvested, and it was put in the storehouse, nothing bad has happened to it. Now at least you must admit that this is a sure thing. Eat a mouthful and you will see!”

Thid Kham lifted the rice to his mouth. He was just about to taste it, but he paused.

“Father-in-law, I can see that the rice grew, it ripened, it was harvested and stored. All this is true. Still I must repeat the words of the Lord Buddha to you,

Dai dai nai lok luan anijang. Nothing is certain.”

The father-in-law could not control his anger any longer. He reached out his hand and slapped the bowl of rice from Thid Kham’s hand.

“Then leave my house! You will never stop with this foolish saying!”

Thid Kham slowly picked up the rice bowl from the floor and looked at his father-in-law.

“But you can see for yourself the wisdom of our Lord Buddha’s words, ” said Thid Kham.

“The rice was planted, it bloomed, it ripened, it was harvested, it was stored, it was cooked, and it was almost in my mouth. And yet it was lost to me. Surely no one here can doubt the truth of this saying,

Dai dai nai lok luan anijang. Nothing is certain.”

And at last his father-in-law was silent.

“Yes, it is true. Dai dai nai lok luan anijang. Nothing is certain.”

Even though the above story is not a Jataka tales, it is a good beginning as it puts us in the Buddhist mood. The aim of this presentation entitled “JatakaTales and Storytelling” is to share general cultural information on the Jatakatales and to relate relationships between the tales and storytelling.

Before I discuss this topic in detail, I would like to explain why I am interested in the Buddhist Jataka tales and storytelling. My major responsibility at Mahasarakham University in northeastern Thailand has been teaching English and American literature to graduate and undergraduate students. My passion is doing storytelling performances. Both my work and my passion came together and mingled after my Fulbright term in 1991-1992. I was translating Phya Khankhaak, the Toad King, during that year. The book was eventually published by Bucknell University Press in 1996.2

|

Not long after I returned to Mahasarakham to continue my teaching career, I discovered that children of Isan or northeast Thailand did not like to speak in their own local dialects. I was alarmed because if they do not speak now, it will be too late. The language may disappear or die out altogether. Besides the language, other rituals and customs associated with language may disappear as well. Thus, I began my storytelling project aiming to engender pride in local language and culture among people of all walks of life, particularly the young children. It became a three-year project beginning in 1995 and ending in 1998. At the onset of the project we had no grant to support us, but a Fulbright visiting scholar. We were lucky to get Dr. Margaret Read MacDonald, a folklorist, a specialist in children’s literature, a librarian, and an internationally known storyteller. We trained 20 students to collect and adapt folktales for performance and to tell stories in the local dialects that they are familiar with. Later, we received some financial support from the James W. H. Thompson Foundation to help with students’ per diem during the visits to all provincial schools in Isan (northeast Thailand). We took the university students to each school and gave storytelling-theater performances in local dialects. Then we gave workshops to teachers so that they could teach and train their elementary school students to tell stories or to collect stories. We gave them a year interval. On our second visit, we asked the teachers to select one student from each class to tell stories to us. Students who could not speak local dialects became interested. We gave partial financial support to the best storyteller and the best story collector in each school to attend our storytelling camp in the summer of 1997. We received partial support from the James W. H. Thompson Foundation for this camp. As part of my job of teaching English, I also offered a course on storytelling in English for English majors and in other dialects for students of other majors. Each year we have had at least ten trained storytellers to help us in giving storytelling performances, workshops, and camps. As a result of the course and with the help of Dr. Margaret Read MacDonald, we brought some students to the United States to tell stories in English during university breaks. We received funding from the John F. Kennedy Foundation of Thailand for the first group of students. For the second group, the students’ parents paid for their trips.

After the project was over, I continued storytelling activities that had been part of the original project such as storytelling tours to schools, an annual storytelling festival and contest, annual workshops for teachers and other interested people, and storytelling camps for children and parents. In doing all these activities, we continued calling attention to the preservation of local dialects and literature. Some participants have been quite helpful to us. They would locate traditional storytellers in their communities for us. Then, we would go out to collect stories. After awhile we would sort out some of these stories and adapt some for further storytelling performances. Among these stories, we found many types such as fairy tales, legends, tricksters tales, fables, elaborate tales, tales of magic, cumulative tales, Jataka tales, and so on. One of the storytellers that we interviewed was Phra Inta Kaweewong from Wat Sa-ahdsombun in Roi-Et. At first, we thought most of his stories were folktales in general, but later we realized that many of them were Buddhist Jataka tales. Thus, I became interested in more of these tales as they are appropriate to adapt for general audiences.

The word Jataka is a Pali word (in Thai and Lao, it is called chadok) referring to the “life stories of the Buddha.” These stories were believed to be told by the Buddha to illustrate certain moral points in his sermons. Later, when his disciples recorded them in the collection called the Dhamma or Buddhist teachings, the lives of some of Buddha’s followers were included. In Thailand and Laos, the Jataka tales are divided into five categories—nibat chadok,atthakatha chadok, dika chadok, panyaat chadok, and chadok mala.3

Nibat Chadok refers to stories in the Tripitaka (the Three Baskets of Dhamma- the Buddhist Scriptures, Book 27 and 28). Nibat means Pali verse in theTripitaka. Each nibat consists of sections and each section consists of Jataka tales. There are a total of 547 tales in the Nibat Chado.4

Atthakatha Chadok refers to stories recorded one thousand years after the Buddha’s attainment of nirvana. The stories were written in prose to explain certain Pali verses from the 547 tales in the Nibat Chadok. Some of these stories were completely new and some were explanations or elaboration of short and unclear stories from the Nibat Chadok. There are 547 stories in this collection as well.

Dika Chadok refers to a collection of explanatory notes in simple Pali, comparing and contrasting the stories from the first two types and explaining Pali grammatical notes.

Panyaat Chadok refers to prose stories in 50 sets of palm leaf manuscripts composed in Khmer by monks from Chiang Mai in northern Thailand . These stories are not the Jataka tales in the Buddhist Scriptures. Stories in this collection are mostly local folktales as well as folktales from Egypt and Persia. The monks that related the stories made them sound like the Jataka tales for teaching purposes.

Chadok Mala are the Mahayana Buddhist Jataka tales translated from Sanskrit texts. Most of the stories have little details on the association of characters to the persons in the Buddha’s lifetime. These stories were composed to be parts of sermons for teaching. Stories in this collection are about various classes of people (high, middle, and low class), describing their ways of life, their clothing, beliefs, and customs. Some of these stories are used to help solve daily problems in people’s lives as well. There are altogether 34 stories; 27 of which are the same as those in the 547 stories in the Buddhist Scripture and 7 are new stories with no sources.

The Jataka tales, no matter which types they are, were told, retold, and composed for one common purpose, to teach. The Buddha, one of the world’s greatest teachers, once described his Dhamma teaching methodology as the four stages of lotus flower. Each stage is compared to the level of human intelligence. The approach to teaching whatever subject matter depends on the level of intelligence of each person. The first group is lotus flowers above the water; they are compared to the most intelligent group of people. In the teaching of the Dhamma, there is no need for any further explanation or illustration. The Buddha could only give a few lines in Pali and they would be understood thoroughly. The second group is the lotus flowers about to emerge from the water; they are compared to relatively intelligent people. There is need for further explanation. In his teaching to this group of people, the Buddha might give the Pali text with some explanation. The third group is the lotus flowers submerged in the water; they are compared to average people. There is need for further explanation plus illustrations. And finally those flowers under the mud are compared to the people with little intelligence; there is no need to teach them. They will become the prey of fish and turtles.

From the Buddha’s analysis of human intelligence, I assume that “the illustrations” refer to stories he told to make his teaching points clear. Thus, we are grateful that there were quite a few average people in his time; otherwise, we might not have these great stories to tell. Indeed, the Jataka book is one of the world’s oldest and largest collection of folk tales. However, when the Buddha gave illustrations, he would state that these were stories from his past lives. Thus, they are his life stories which have been called Jataka or chadok. The Buddha’s disciples later retold these stories in their sermons and teachings. More stories may have been added to the original collections to convince people to follow the teachings. Thus, we have the many types of Jataka tales as mentioned earlier. In the five hundred some stories, the Buddha was born a man, a good spirit, or one of the higher animals, and he is usually the hero of the story. In each of his past life stories, the Buddha was called “the future Buddha or the Bodisat.” In the last ten lives before he was born as the historical Buddha, the Buddha was born a noble prince or king, accumulating the highest virtues befitting the Buddhahood. In these ten lives (Phra Te-mii, Phra Chanok, Suwannasarm, Nemiiraj, Phra Mahosot, Phuritat, Chandra Kumarn, Narort, Witoon, and Phra Wetsandorn), there are many more sub-stories within the ten tales.5

An example is the story called Jitjun, the Clever Turtle of Yamuna which is an episode in the story of Phurithat Jataka. King Brahmadatta of Banares appointed his only son the second king. After awhile he became suspicious that his son would overthrow him. Thus, he sent his son in exile in the forest where he became an ascetic. A naga maid named Manwika fell in love with the prince and they became husband and wife bearing two children, Prince Sakhon Brahmadatta and Princess Samutcha. After King Brahmadatta died, the noblemen and ministers of Banares came to invite the Prince to king of Banares. Manwika Naga decided to return to her Naga city and the Prince and his two children returned to Banares. One day when Prince Sakhon Brahmadatta and Princess Samutcha were playing near the lotus pond, a turtle emerged from the water and frightened the two royal children. The king was so infuriated that he ordered his ministers to punish the turtle. Each minister would suggest a way to punish the turtle, but the turtle would speak bravely that none of the punishment would hurt him. When one of the minister who could not swim suggested that they throw the turtle and drown him, the turtle jumped up and pretended to be so scared. So, they threw the turtle in the Yamuna River. So the turtle was safe, but he swam down deep in the Naga city and created another mischief that caused Princess Samutcha to be married to a naga king, Thatarot who bore four sons and one of them was the Bodisat called Prince Phurithat. And the main plot of the the story of Phurithat Jataka continues.

As the Buddha retold the Jataka tales, he was actually telling stories. Thus, storytelling and the Jataka tales have been closely related since the stories were first retold.

Besides retelling the Jataka tales to teach certain moral points to average people to make his teachings clear as mentioned above, the Buddha also retold stories to teach high rank people without embarrasing them.

Once King Brahmadatta of Banares was very talkative. He was so talkative that none of his ministers could give any advice or suggestions. Thus the story of “The Talkative Turtle” or “Kacchapa Jataka” was told to him

An example is the story called Jitjun, the Clever Turtle of Yamuna which is an episode in the story of Phurithat Jataka. King Brahmadatta of Benares appointed his only son the second king. After awhile, the king suspected that his son would overthrow him. Thus, he exiled his son to the forest where he became an ascetic. A naga maid named Manwika fell in love with the prince and they became husband and wife bearing two children, Prince Sakhon Brahmadatta and Princess Samutcha. After King Brahmadatta died, the noblemen and ministers of Benares came to invite the Prince to become king of Benares. Manwika Naga decided to return to her Naga city and the Prince and his two children returned to Benares.

One day when Prince Sakhon Brahmadatta and Princess Samutcha were playing near the lotus pond, a turtle emerged from the water and frightened the two royal children. The king was so infuriated that he ordered his ministers to punish the turtle. Each minister suggested a way to punish the turtle, but the turtle would speak bravely that none of the punishments would hurt him. When one of the ministers who could not swim suggested that they throw the turtle and drown him, the turtle jumped up and pretended to be very scared. So, they threw the turtle into the Yamuna River. So the turtle was safe, but he swam down to the Naga city and created another mischief that caused Princess Samutcha to be married to a naga king, Thatarot with whom she bore four sons. One of the sons became the Bodisat called Prince Phurithat. And the main plot of the story of the Phurithat Jataka continues.

As the Buddha retold the Jataka tales, he was actually telling stories. Thus, storytelling and the Jataka tales have been closely related since the stories were first retold.

Besides retelling the Jataka tales to teach certain moral points to average people to clarify his teachings, the Buddha also retold stories to teach high rank people without embarrassing them.

Once King Brahmadatta of Benares was very talkative. He was so talkative that none of his ministers could give any advice or suggestions. Thus the story of “The Talkative Turtle” or “Kacchapa Jataka” was told to him.6 In this story, a turtle and the two swans were friends. One day, the two swans invited the turtle to visit their home in a far away land. The turtle wondered how he could go there without wings. The two swans told him, “We can take you, if you will only hold your tongue and say nothing to anybody.” The two swans had the turtle bite the middle of a stick. Then, they took the two ends of the stick and flew up into the air. Then, some villagers called out, “Look, two swans are carrying a turtle!” The turtle did not like this so he called out to them, “If my friends choose to carry me, what is it to you, you wretched slaves!” Then, the turtle fell and split in two! Once, the king heard the story, he refrained from talking too much, and “became a man of few words.”7

The Buddha also told stories from his past life to relate relevant events in his lifetime. For example, once the Buddha’s cousin, Devatta, wanting to harm the Buddha by feeding alcohol to a bull elephant, and then releasing it to charge at the Buddha. Ananda, the Buddha’s most faithful disciple, threw himself between the Buddha and the elephant. But the Buddha was able to subdue the elephant and save Ananda’s life. After the incident, the Buddha related a similar story that had happened in his past life about the Great Golden Geese.8

Once King Samyama and Queen Khema reigned in Benares. Queen Khema had a dream that she saw two gold-colored geese. She wanted to see them in real life so she told the king about this. The king at once ordered his hunter to catch the geese. After he patiently observed the golden geese, the hunter was able to trap the Goose King with a snare. The other geese including the Goose King’s captain flew away. When the captain realized that the Goose King was trapped, he returned to stand near his king. The hunter was surprised to see that only one goose was trapped, but there were two geese awaiting their fate. Then, the captain told him that the trapped goose was his king and he would not leave. He said to the hunter, “You must not take him. I too am gold-colored. If you desire his feathers, take mine; if you want to tame him, tame me instead; if you wish to make money, make it by selling me. He is my king and I serve him. I cannot leave him to face an evil fate alone while I fly to safety.” The hunter was in awe and raising “his joined hands to his forehead in respect, he stood joyously proclaiming the virtues of the two birds.” He decided to free the Goose King. Then, the captain asked why the hunter caught the Goose King. The hunter told them that he received an order from the king. So, the captain suggested that the hunter take them to the king so that the hunter could receive honor and fortune in return. Once there, the hunter told the king about what had happened. Then king welcomed the two geese and gave treasures to the hunter. Then the king asked the goose captain to give a sermon to the assembly, but the goose captain said he was only a servant and could not give a sermon “when to my left sits my king, wise and virtuous of character and beautiful to behold, while on my right sits the mighty King of Benares.” The king understood that the captain was “an example of loyalty and service” to his lord. Then, the king of Benares “begged the bird to preach his wisdom to the gathering.” After the sermon, the king let the birds go.

After telling the story, the Buddha related that the hunter was Channa, his companion, that the king of Benares was his disciple, Sariputta, and that Queen Khema was the nun with the same name. His chief companion, the goose captain, was Ananda. “Both . . . had shown his loyalty and his willingness to sacrifice himself for the Buddha.”

After the time of the Buddha, his disciples have told Jataka tales of all types to explain moral points as well. Later these stories are told to convince listeners to follow proper conduct or behavior appropriate to each community. Of course, these stories are entertaining as well as didactic and that is why they work. In the family, parents tell these stories to teach their children to behave properly. In schools, teachers tell these stories for disciplinary reasons.

Some of these stories have been embedded in rituals. One example is the story of the previous life of the Buddha as the Vessantara prince. 9 As the Prince was a selfless giver, the recitation of the story is implicitly persuading the participants to be selfless givers as well. In Thailand, Laos, Burma and Cambodia, the recitation of Prince Vessantara is the main Buddhist festival of the year. Festivities center on its recitation by monks. In Thai, the story is known as Mahachad, ‘the Great Jataka’, and the main religious festival is calledBun Phra Wet (Phra Wet = Vessantara). The recitation of the story starts early in the morning and ends at about eight in the evening and must be completed within one day. First, there is a sermon on the battle with Mara, the god of death and desire, followed by a recitation of a thousand verses of Pali text. Pali verse is chanted by a monk (or monks). Then the audience throws puffed rice at the Buddha image installed in the public prayer hall. Then the monks ‘translate’ the sacred Pali text into comprehensible Thai. As the monks are reading the story, people donate some money to the temple. The money is used to repair the temple or to get necessary supplies for the temple. The festival usually takes place in March during the dry season which is also the hottest time of the year. The symbolism of the water-giving powers of Vessantara’s magic albino elephant has a special potency at this time of year when farmers wait in anticipation for the life-giving rains and their return to planting rice in rain-soaked fields. The back- ground information for this explanation is taken fromBun Phra Wet in Laos.10

As mentioned earlier, the Jataka tales have been a great resource for storytellers all over the world. In storytelling, it is our duty to be responsible for what stories we tell as these stories are so effective and long-lasting in listeners’ minds and ways of life. Thus, stories that we tell must be appropriate to tell to a general audience, both young and old. Most of the time, Jataka tales are our most convenient choices. However, if we choose any story from the Scripture to tell, we must tell it with respect. Other stories, that have been adapted or localized, we can tell in fun and more lively manners.

Some Jataka stories have been changed depending on the places and people who tell them. For example the Jataka tale of the Talkative Turtle told by people in northeast Thailand and Laos is quite different from the one from the original story.

The Swans and the Turtle11

Once a couple of swans, a husband and a wife, sighted a pond full of fish. So, they flew down to have some fish, not knowing that a turtle was guarding the pond.

“Why are you eating fish in my pond without asking for my permission?” asked the turtle.

“Oh, does this pond belong to you?” asked the swans.

“Yes, I have been guarding this pond for along time,” said the turtle.

“We are so sorry. We thought nobody owned this pond,” apologized the swans.

“Since, this pond belongs to you, may we have some fish in your pond?” politely asked the swans.

“Now that you asked, you may have some fish in this pond.” said Turtle.

After that, the swans visited the turtle everyday. Soon they became fast friends. One day the swans thought they would do something nice for the turtle in return for sharing fish with them.

“Friend Turtle, we appreciate your sharing the fish with us. We would like to do something nice for you in return. Is there anything we can do for you?”

The turtle always had a dream that he could travel in the air and enjoy looking at the scenery from a different angle. So he said, “Are you sure?”

“Yes,” said the swans.

“I dream that I could fly high in the air and enjoy the scenery below,” the turtle told his friends.

“Oh, that is not a problem for us. We can help you fly,” said the swans.

“How? I don’t have wings like you. I have this heavy shell on my back with these four short legs,” said the turtle.

So, the swans explained, “Well, we can get a good size stick and hold on to the two ends with our beaks. You could bite hard on the middle. Then, you can fly with us.”

The turtle could hardly wait to fly with the swans.

“Yes, let’s go, let do that now,” he said.

The swans held on tight to the two ends of the stick and the turtle bit hard in the middle.

Before the swans took off, they said to their friend.

“Friend Turtle, be sure to keep biting on the stick. Don’t ever open your mouth no matter what happens. Or, you may fall onto the ground. And we won’t be able to help you.”

“Yes, I promise not to open my mouth,” said the turtle.

So, the swans flapped their wings and slowly lifted the turtle in the air.

The turtle looked down and saw the pond getting smaller and smaller.

He was so happy, but he kept his mouth shut.

He saw the top of the trees for the first time in his life.

He was so happy, but he kept his mouth shut.

“Oh, this is so much fun. I can’t wait to tell my other turtle friends that I CAN FLY.”

He was so happy, but he kept his mouth shut.

As they flew past a ricefield, they saw a boy and a girl walking their buffaloes to graze on grass in the ricefield. The boy looked up and saw . . .

he pointed up and alerted his friend to look up.

“Look two swans are carrying a turtle,” he said.

The girl looked up and said, “No, a turtle is carrying two swans.”

“No, two swans are carrying a turtle,” the boy insisted.

“Can’t you see a turtle is carrying two swans!” she said.

When the turtle heard what the argument was about, he thought,

“Yes, the girl is right. TURTLE IS CARRYING TWO SWANS.”

He was so proud of himself, but he kept his mouth shut.

But then the boy’s voice came loud and clear.

“No, two swans are carrying a turtle,” said the boy, pointing up.

The turtle’s pride was hurt so he opened his mouth to argue with the boy.

“Turtle is carrying two swans . . .”

Turtle’s body smashed onto the ground. Turtle’s blood and guts went all over and it splashed on the boy’s armpit as he was pointing.

“Oh, this smells bad.” The boy tried to wash and scrub his armpit, but no matter how hard he scrubbed and washed, the smell was still there.

The girl did not get it as badly as the boy.

Since then boy’s or men’s armpits smell and the smell is called 0uhg8jk (khi tao)which means . . . “turtle’s excrement.”

Girl’s or women’s armpits do not smell as bad, at least this is true in northeast Thailand and Laos.

The last set of the Jataka tales are those that are not in any Buddhist Scriptures or in the five types mentioned above, yet the tellers claim that they are the Buddha’s birth stories. One example of this type of Jataka tale is found inPhya Khankhaak, or the Toad King 13

which is a Thai/Lao fertility myth, celebrating “the battle victory of a human king, Phya Khankhaak” over the highest god, Phya Thaen, to bring peace and prosperity to all creatures in the universe.

At the beginning the teller makes a claim that Phya Khankhaak, the Toad Kingis a Buddhist Jataka tale by saying:

| I will tell the story of a past life of the Buddha |

| While he was revolving in the Cycle of Life on Earth 14 |

Then at the middle of the story, after the victory of the Toad King’s army, Phya Khankhaak gave a sermon to teach the rain god, Phya Thaen. The teaching is clearly in the style of the historical Buddhist teachings.

Like the Buddha in his last meditation before attaining enlightenment.

As the Lord was approaching his most enlightening phase in his meditation,

Phya Mara, the great tempter,

The conqueror of great magical knowledge and power

Appeared to lure the Buddha in his mediation,

As he had done to every Enlightened One before.

Mara was obsessed with great jealousy for the Enlightened One,

Fearing that the Buddha Lord

Might become most distinguished of all in his enlightenment.

Thus, Mara mounted his great elephant named Mekkhala Luang

And led his army to bait the meditating Buddha 15

|

At the end, the teller reconfirms the authenticity of the tale as a true Jataka tale by relating a list of characters in the story to persons in the Buddha’s lifetime.

| Now let me summarize this final chapter of this great Buddhistic legend |

| In a Jataka collection of didactic verse tales. |

| Those who are wise should memorize this ancient story |

| Related to chronicles for teaching Dhamma, the right principles. |

| The original king Phya Ek-karaj the great |

| Was later reincarnated as the Buddha’s father. |

| As for the original queen of Phya Ek-karaj, |

| She was reborn as Nang Yasotharaphimpha, the Buddha’s wife. |

| The Naga and the Garuda Kings blessed with great magical powers |

| Were reincarnated as the greatly renowned disciples, |

| Mokkhanla and Saribut. |

| Those countless numbers of soldiers, |

| Subjects, and citizens were reborn |

| As Buddhists who practice and observe the Buddha’s Teachings. |

| Finally, His Majesty Phya Khankhaak, |

| The meritorious ruler at that time, |

| Was reincarnated as the great world renowned Buddha, truly. |

| This is a true account of Phya Khankhaak |

| Which has been recited in the fifty lives |

| Of the Buddha-to-be, dear readers.16 |

With that, I would like to end this presentation with a short version of PhyaKhankhaak, the Toad King, focusing on the episode entitled, “The Gathering of the Toad King’s Army.” 17 Normally, by telling this episode of the story, it is symbolic of the rain request ceremony and it rains. So, here it is:

The king and queen of Inthapatthanakhon gave birth to a meritorious son who was as ugly as a toad. The prince was named Khankhaak, which means toad. When Khankhaak was twenty years old, Indra came to make him handsome, give him the most beautiful wife, and built him the most splendid castle. Realizing the prince’s merit, the king resigned from the throne to allow his son to become king. Phya Khankhaak became a powerful king, with all the kings from all human, demon, animal, and angel lands as his protectorates. Every creature in the universe came to pay tribute and homage to Phya Khankhaak, but neglected to pay tribute and respect to Phya Thaen, the rain god. This behavior so humiliated Phya Thaen that he became infuriated with Phya Khankhaak. Phya Thaen then refused to let the naga play in his lake in heaven. As a result, the whole universe was faced with the catastrophe of drought. After asking the Naga King for the cause of the drought, Phya Khankhaak organized a great army of humans, animals, demons, and angels and marched up to heaven to fight Phya Thaen.

At this point, a particular type of song called soeng is used to recruit all kinds of creatures to march to fight Phya Thaen, the Rain God.

Oh, oh, what a woe! Thaen has been our foe,

For he refused to bestow rain to earth.

Come all of us. Let us go to fight Thaen.

From that crowd come wasps, hornets, and bees.

Those beautiful creatures are deer with bright eyes.

Those with golden bodies are beautiful angels or devata.

This crowd of beings are frogs and toads of all kinds.

Those dignified animals are garuda, naga, and lions.

Oh, oh, what a woe! Thaen has been our foe,

For he refused to bestow rain to earth.

Come all of us. Let us go to fight Thaen.

Those approaching are woodmites, termites, dogs and bears.

And these are eagles, porcupines, civet cats, and tigers.

Those splendid creatures are pheasants and swans.

Those cheerful creatures are apes, monkeys, elephants and horses.

Those in the front row are flying lemurs and cuckoo birds.

Oh, oh, what a woe! Thaen has been our foe,

For he refused to bestow rain to earth.

Come all of us. Let us go to fight Thaen.18

When the army was ready, Phya Khankhaak marched up to heaven to fight Thaen. After a long, perilous, and miraculous battle, Phya Khankhaak won. He then taught Phya Thaen to be just and to bestow rain to the universe seasonally. After enjoying Phya Thaen’s heaven for a few months, Phya Khankhaak came back to rule the fertile earth happily. Every once in a while, Phya Khankhaak would recount the story of how he led a great army to fight with Phya Thaen and how he enjoyed spending some time in heaven after his victory. Later, many people retraced Phya Khankhaak’s way to heaven and went to learn all kinds of magical knowledge and power. They came back to earth and began to test their powers. They fought until everyone on earth was completely destroyed. Corpses piled up and became a mountain. At the foot of the mountain grew a lake called Nongkasae. The story ends with the narrator relating each character to a person in the historical Buddha’s lifetime.

|

Notes

1. The Pious-Son-In-Law was retold by Dr. Margaret Read MacDonald, Adapted from THAI TALES: FOLKTALES OF THAILAND by Supaporn Vathanaprida. (Libraries Unlimited, 1994).

2. Phya Khankhaak, the Toad King: An Isan Fertility Myth in Verse, translated by Wajuppa Tossa; original transcription by Phra Ariyanuwat, Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 1996.

3. Sap Prakobsuk, Wannakhadichadok (Buddhist Literature, the Jataka Tales), Bangkok: Odean Store, 1984, pp.14.

4. Loc. cit.

5. Ibid, p. to be recheck. p.?

6. V. Fausboll, edited in the original Pali, translated by T. W. Rhys Davids, Buddhist Birth Stories or Jataka Tales, N.Y.: Arno Press, 1977, pp. 8-11.

More of the Buddhist Jataka Tales could be found in the following sources:

The Golden Deer, is the same story as Golden Foot, inspired by Nazli Gellek, adapted by Karen Stone, illustrated by Rosalyn White, [Emeryville, Calif.] : Dharma Pub.,

c1993. Golden Foot is one of the series of the Jataka Tales Series published by the same press. Among these are Heart of Gold, The Spade Sage, A Precious Life, Three Wise Birds, Courageous Captain, The Best of Friends, The King and the Goat, The Hunter and the Quail, The Parrot and the Fig Tree, The Proud Peacock and the Mallard, Great Gift and the Wish-Fulfilling Gem, A King, a Hunter, and a Golden Goose, The Rabbit Who Overcame Fear, The King and the Mangoes, The Value of Friends, The Rabbit in the Moon, The Power of a Promise, The Magic of Patience, The Fish King’s Power of Truth.

A Treasury of Wise Action : Jataka Tales of Compassion and Wisdom. Berkeley, CA : Dharma Publishing, 1993.

Babbit, Ellen C., Jataka Tales; Animal Stories, illustrations by Ellsworth Young. New York,

Appleton-Century [c1912]

________. More Jataka Tales, illustrations by Ellsworth Young. New York: The Century co., 1922.

Jones, John Garrett. Tales and teachings of the Buddha : the Jataka Stories in Relation to the Pali Canon, London ; Boston : G. Allen & Unwin, 1979.

Khan, Noor Inayat. Twenty Jataka Tales, illustrated by H. Willebeek Le Mair. Rochester, Vt. : Inner Traditions International : Distributed to the book trade in the U.S. by

American International Distribution Corporation, [1991].

Wray, Elizabeth, and others, Ten Lives of the Buddha; Siamese Temple Paintings and Jataka Tales, New York: Weatherhill [1972].

7. Ibid., p. (to be checked)

8. Carl W. Ernst, The Golden Goose King, Chapel Hill, NC: Parvardigar Press, 1995

9. The Perfect Generosity of Prince Vessantara: A Buddhist Epic. Cone, Margaret and Richard F. Gombrich, trans. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1977. Here is the summary of the story ofPrince Vessantara.

The story takes place in India, the source of the original story. In brief, it is about a prince, Wetsandorn in Thai, Vessantara in Pali. Prince Vessantara is the son and heir of Sanjaya, King of the Sivis, and of Queen Phusati. The prince lives in the capital with his wife Maddi (Matsi in Thai) and their small son and daughter. His generosity is unique. He owns a magic white elephant that guarantees plentiful rain, important in an agrarian economy. But he gives it away to a brahmin emissary from another kingdom, which enrages the citizens. They compel King Sanjay to force Prince Vessantara and his wife, Maddi, who insists on accompanying him and their children, to go into exile. Before leaving, the prince gives away all of his possessions, making the “gift of the seven hundreds’. After a long journey on foot, they reach a spot in the mountains, where they settle down. Husband and wife make a vow to live in chastity. Shortly, a vile old brahmin (a member of India’s highest caste) by the name of Jujaka, who is nagged at home by his young wife demanding that he find her servants, arrives to ask Vessantara for his two children. He gives them up in another act of detached generosity while his wife is off gathering food in the forest. In one of the most touching scenes in the narrative, Maddi swoons in grief upon learning of the loss of her children. (This is one of the reasons the story is so popular among women.) The next morning the king of the gods, Sakka (Indra) is afraid that Vessantara will next give away his wife and be left completely alone. So he comes in the disguise of a brahmin and asks for her, only to give her back immediately. Having received her back as a gift, Vessantara is no longer allowed by social convention to dispose of her. Subsequently, Jujaka and the children come to the court of King Sanjaya, where he ransoms his grandchildren and Jujaka, much to the delight of the listener, dies of gluttony. The king takes his retinue to the mountains and invites Vessantara and Maddi to return, and they do so in a grand procession. As in all traditional Indian stories, the story has a happy ending. The family is reunited, all of Prince Vessantara’s possessions are returned to him, and they all live happily ever after.

For more information on the story of Prince Vessantara and the use of the classic epic in modern Thai literature, please go to the following site:

http://www.seasite.niu.edu/Thai/literature/sridaoruang/matsii/matsii2.htm

10. Photo by Bounhome Vongdavanh and story by P. Phouangsaba, “Boun Phravet Festival” in Visiting Muang Lao Magazine, July-August 1999, p. 19.

11. A Jataka tale adapted from the version by Phra Inta Kaweewong from Roi-et, retold in English by Wajuppa Tossa and Prasong Saihong.

When this Jataka story is told by a famous American storyteller, Dianne Ferret, at the annual storytelling festival in Joneborough in Tennessee in October 1998, it was the story of Turtle and Eagles.

12. Turtle of Koka was retold by Margaret Read MacDonald in Folktales and Storytelling by Wajuppa Tossa and Margaret Read MacDonald, Mahasarakham, Thailand: Aphichatkanphim, 1996.

13. Phya Khankhaak, the Toad King, p. 31.

14. Phya Khankhaak, the Toad King, p. 35.

15. Phya Khankhaak, the Toad King, p. 115.

16. Phya Khankhaak, the Toad King, p. 134.

17. Folktales and Storytelling, p. 56.

18. This version of the verse was composed by Wajuppa Tossa in Folktales and Storyteling, pp. 54-56. The original version of the story is from Phra Ariyanuwat Khemajari, Phya Khankhaak, 1970.

|

SANCHI STUPA

Emperor Asoka (273-236 B.C.) built stupas in Buddha’s honour at many places in India. Stupas at Sanchi are the most magnificent structures of ancient India. UNESCO has included them as one of the heritage sites of the world. Stupas are large hemispherical domes, containing a central chamber, in which the relics of the Buddha were placed. Sanchi stupas trace the development of the Buddhist architecture and sculpture at the same location beginning from the 3rd century B.C. to the 12th century A.D.

Asoka when he was a governor married Devi, the daughter of a respected citizen of Vidisha, a town 10 km from the Sanchi hill. Prince Mahendra visited Sanchi with his mother before leaving for the island of Lanka for taking Buddhism there. Emperor Asoka had put up at Sanchi a pillar edict and a stupa containing relics of the Buddha. Addition of new stupas and expressions in stone of legends around the life of the Buddha and the monastic activities at the Sanchi hill continued under several dynasties for over fifteen hundred years. Also, the Brahmi script could be deciphered from the similarities in inscriptions carved at different places in the main stupa.

Sanchi stupas are noteworthy for their gateways as they contain ornamented depiction of incidents from the life of the Buddha and his previous incarnations as Bodhisattvas described in Jataka tales. Sculptors belonging to different times tried to depict the same story by repeating figures. The Buddha has been shown symbolically in the form of tree or through other inanimate figures. One of the sects of Buddhism opposed depiction of the Buddha by a human figure.

The top of the Asoka pillar, which comprises of four lions, has been kept in the museum maintained by the Department of Archaeology. The size and the weight of the pillar point to advanced construction technology that was existent at the time of Asoka. It must have been an incredible feat of engineering to bring the stone for carving the pillar from the mine to Sanchi and installing it up the hill.

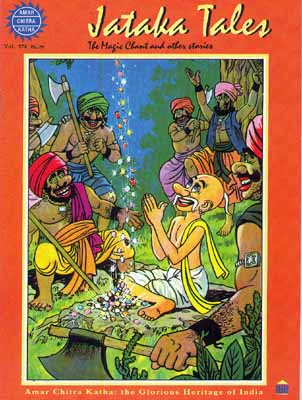

Jataka Tales

Jataka tales as do Aesop’s fables teach generosity and self-abnegation based on previous lives of the Buddha as Bodhisattvas. As a Bodhisattva he took births as man, animal or bird. It is believed that the Buddha accumulated virtue by good deeds he did as Bodhisattvas and had attained merit for achieving nirvana in his last birth when he was born as the prince Siddhartha.

The Great Monkey Jataka

In this tale Bodhisattva was born as a monkey. He was the king of eighty thousand monkeys. They lived happily on a mango tree by the side of the river Ganges and ate its tasty fruits. Brahamadatta, the king of Varanasi, on knowing that the mangoes of the tree where the monkeys lived were very delicious and sweet, surrounded the mango tree with his soldiers. They started killing the monkeys with arrows. The monkey king at the risk of his life decided to save the lives of the other monkeys. He jumped across the river and found a bamboo pole. When he found that the length of the pole was not enough for crossing the river he tied one end of the bamboo pole to the mango tree and its other end to his waist. He stretched his body and made a living bridge across the river. His friends crossed to safety by using the bridge consisting of the bamboo pole and the stretched body of their king. Devadatta who was also a monkey was the rival of the monkey king. Devadatta found in this situation an easy opportunity for killing the monkey king. He jumped on him violently. The monkey king’s heart ruptured out of his body. When Brahamadatta saw the supreme sacrifice of the monkey king his heart filled with sorrow. The Bodhisattva before dying gave a sermon to Brahamadatta. Brahamadatta performed the last rites of the monkey king with honour and respect.

In some of the panels on the gateways of the stupa scenes from this Jataka tale have been shown.

Jataka Tales

Six-tusked Elephant Jataka

In one of his previous births the Bodhisattva was born as a six-tusked elephant. He lived in the Himalayas with his two female elephant wives named Chulasubhudha and Mahasubhudha . Chulsubhudha despised her husband as she thought that he loved his other wife more than her. She prayed that in her next life she may be born a beautiful girl and have the good fortune of marrying the king of Varanasi. Her deep jealousy and the desire to take revenge from her husband resulted in her death. As she had wished, she was born in her next birth a beautiful girl and became the wife of the king of Varanasi. She feinted illness and pleaded her husband to ask Sonuttar, the king’s archer, to bring for her the tusks of the six-tusked elephant. The hunter wounded the six-tusked elephant with arrows and tried to pull out his tusks. The elephant took pity on the hunter and helped him in pulling out his tusks. When the tusks were given to the queen she repented her wanton act and died out of grief.

In some panels on the gateways of the main stupa scenes from this tale have been shown.

Jataka Tales

The Vessantra Jataka

In one of his previous births the Buddha was born as the prince Vessantra. The prince was very generous. He gifted away the elephant that had supernatural power of bringing rains to the Brahmins of Kalinga, as it was undergoing drought. Vessantara’s father, the king, was so upset by this gesture of his son that he ordered the prince to leave his kingdom with his wife, the son and the daughter. Vessantra drove out of his father’s country in a chariot driven by four horses. As he left, he gave away the carriage and the horses for asking, and settled in a hut in the forest with his family. Soon he gave away his children to a wandering ascetic, who needed them to do begging for him. Finally, he disposed off his wife in a similar manner. But all ended happily, for those who had asked him for his most precious possessions were gods in disguise, who had decided to test his generosity. They restored to him his family and Vessantra was received back by his father.

In some of the panels on the gateways of the stupa scenes from this Jataka tale have been shown.

Jataka Tales

The Sama Jataka

This Jataka tale is about the extreme devotion of the Bodhisattva Sama to his parents. Sama’s parents had become blind because of snake bite. Sama devoted his life for serving his blind parents. One day when Sama was filling his pitcher with water from a river, the king of Varanasi miss took him for a deer and shot him dead with an arrow. When the king saw the pitiable condition of Sama’s parents his heart filled with remorse. The sorrowful king decided to dedicate his life in taking care of Sama’s parents. The lamentations of Sama’s parents and the noble gesture of the king touched the heart of a goddess who witnessed this situation. The goddess with her magical powers restored the eye sight of Sama’s parents and made Sama alive.

In some of the panels on the gateways of the stupa scenes from this Jataka tale have been shown.

Jataka Tales

An album of pictures from Sanchi has been put on this website. Individual pictures can be accessed from their thumbnails.

http://artfoundout.blogspot.com/2009/03/jataka-tales-scroll-from-thailand.html

Jataka Tales – scroll from thailand

An Appeal - Many of the Indian artists mentioned on this site live in poverty. Even with the recognition they have received, most have not been able to find a place for themselves in the art market. The artists with the greatest needs are Ganesh, Teju and their children. They have no home to speak of and at times do not have money even for food. It may be impossible for most Westerners to truly comprehend the poverty that is their reality. You can help, simply by purchasing their work. I can arrange this and all the money will go directly to the artists.If you would like to collect their work, contact me at the e-mail listed on my profile.

An Appeal - Many of the Indian artists mentioned on this site live in poverty. Even with the recognition they have received, most have not been able to find a place for themselves in the art market. The artists with the greatest needs are Ganesh, Teju and their children. They have no home to speak of and at times do not have money even for food. It may be impossible for most Westerners to truly comprehend the poverty that is their reality. You can help, simply by purchasing their work. I can arrange this and all the money will go directly to the artists.If you would like to collect their work, contact me at the e-mail listed on my profile.

![[DSCN0337.jpg]](http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_WfpsDFzTM0A/SalqbtU3YaI/AAAAAAAACaQ/9rdSPFYG-Ws/s1600/DSCN0337.jpg)

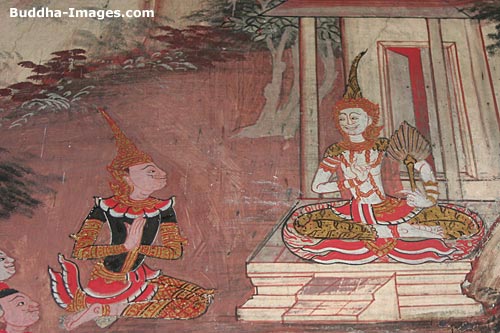

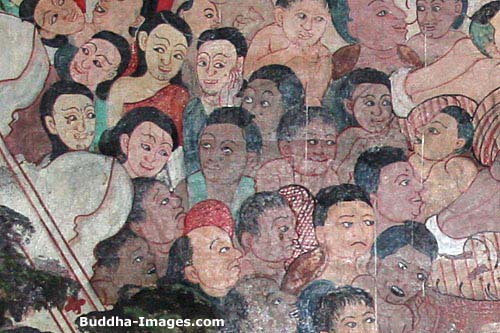

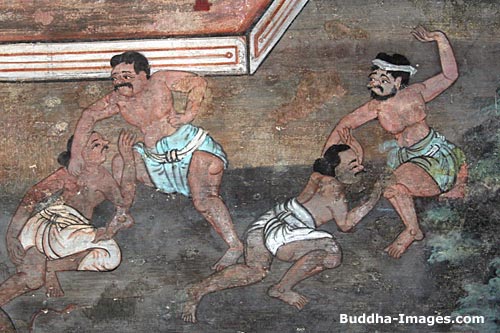

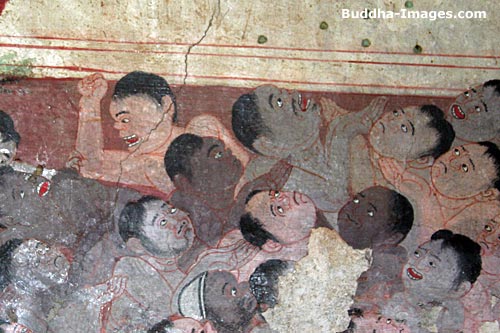

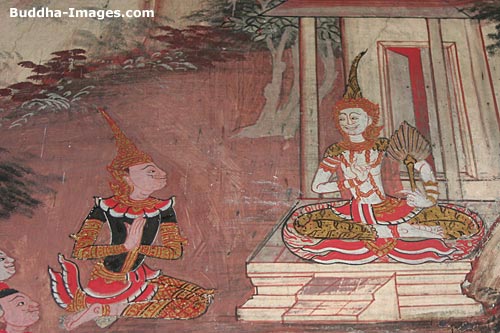

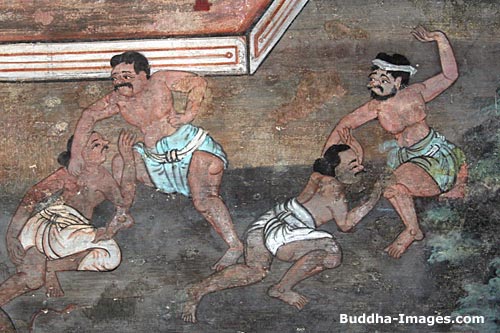

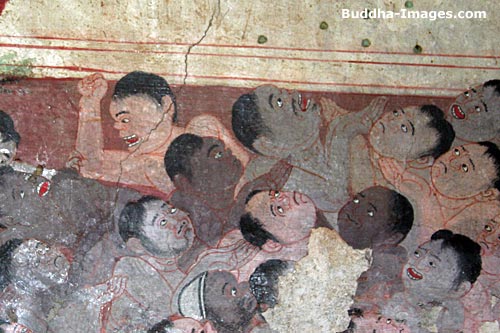

In northeastern Thailand, there is a tradition of scroll painting on fabric illustrating the Jataka Tales. These morality stories are of the previous lives of Buddha before he was born for the last time to become the Buddha.

In northeastern Thailand, there is a tradition of scroll painting on fabric illustrating the Jataka Tales. These morality stories are of the previous lives of Buddha before he was born for the last time to become the Buddha.

Due to tradition and climate issues, it is difficult to see scrolls that are over 50 years old. Scrolls were replaced when damaged or would be discarded (at times, burnt) when new ones were commissioned as gifts to a temple.

These scrolls are remarkable in their diversity of execution and hand. In a country with so many people trained to conserve and restore temple wall paintings, it is interesting to see that often these scrolls were the work of artists not instructed in a more formal manner.

Jataka Tales scrolls are often extremely long, at times over thirty feet in length and on average, three and a half feet wide. Many older works have not survived intact and it is common to see only fragments.

The examples on this page are of several different scroll fragments, presented to show the range of artistic style.

http://www.buddha-images.com/10jatakas.asp

The Jataka Tales - Previous Lives of the Buddha

The Jataka Tales are narratives about the previous lives of the Buddha (that is, before he was born for the last time to become the Buddha). In Thailand, the last 10 Jatakas (there are many, many more, a lot just involving animals) are often depicted along the longitudinal walls of temples. Thai mural paintings (both of the Jatakas, and of the Life of the Buddha) are often in various stages of disrepair. Almost all the paintings that are used as illustrations for the narrative of the 10 Jatakas below, are from Wat Yai Intharam in Chonburi province. Unfortunately, the Ubosoth of Wat Yai Intharam is not easily open to the general public. Some part of the paintings are likely a few hundred years old, some likely overpainted in subsequent years (not really sure, if anyone really knows exactly what is new and what is old).

All of the paintings follow certain rules in the composition of the images. There usually are some parts that make it easy to the believer or someone who has taken interest in Thai mural temple paintings, to recognize the particular Jataka in question. Going through the narratives, and the pictures shown, will make your next visit to a Thai temple much more interesting, since you will know what you are looking at.

The narratives (slightly modified) recounted come from the book : Ten Lives of the Buddha by Elizabeth Wray, Clare Rosenfield, Dorothy Bailey and Joe Wray (photography). Besides the stories here, this book, published first in 1973, gives a lot more information about the Jataka Tales in general, and Thai Temple Paintings. A reprinted softcover version is still available through Amazon.

The pictures in the book are different from the pictures on this website. All pictures accompanying the Jataka Tales by Guido Vanhaleweyk, Bangkok.

Temiya Jataka - Temiya, the mute Prince

There lived a king of Benares who, despite all his riches and plenty, still was unhappy. For though he had sixteen thousand wives, he had no son nor daughter. Each and every one of his wives prayed that she might bear a son to him. His main queen, Candadevi, asked of the great god Sakka : “If through my life I have done only good, a son be born to me.”

When her plea reached Tavatimsa heaven, the throne of Sakka, king of the gods, became warm, an sign of an injustice on earth. Sakka realized that he had overlooked the virtues of Queen Candadevi. Immediately, from among the deities in heaven he chose the Bodhisatta, who he knew would serve as a model of self-denial for the kingdom of Benares, and sent him down to earth to be conceived in the queen’s womb. In addition, to five hundred nobles’ wives he sent five hundred more beings to be born as the Bodhisatta’s attendants. When the queen felt as though her womb contained a diamond, she knew she was pregnant. She informed the king, and both were happy. Great care was taken until the day of her delivery. Upon hearing the words of the birth of his son, the new father felt paternal affection lighten his heart. At the same time, five hundred nobles’ gave birth to infants who were to grow up with the Bodhisatta and serve him. The Bodhisatta was given sweet milk from sixty-four wet nurses selected because of their flawless beauty. After presenting the nurses to the queen the king felt generous and told her he would grant anything she asked. However, the queen postponed her request, as she preferred to wait for the day when she might need it.

On the occasion of the naming of the child, the Brahmins proclaimed that the royal son and heir to the throne possessed every mark of good fortune. The king named his son Temiya-Kumaro, meaning ‘prince drenched with water’, because both his birth and the rainy day on which he was born were very wet.

When Temiya was only one month old, he was dressed up for his first public appearance and brought to the throne of his father to sit on his knee. Many courtiers admired his beauty and murmured their approval. Four robbers were then brought before the king to be judged. Temiya witnessed his father sentence one robber to a thousand strokes from thorn-baited whips, another to imprisonment in chains, a third to death by the spear, and a fourth to death by impaling. The infant Bodhisatta was terrified at his father’s apparent cruelty and thought to himself, “A king acts as judge, and so he must perform cruel actions every day. By condemning men to death or torture, he will however himself be condemned to hell.”

The next day, awakening from a short nap and looking up at the great white umbrella above him, the infant began to think of what it would mean to be king. These thoughts alarmed him, even more so as he remembered a previous existence in which he himself had reigned as king of Benares for twenty years. As a result of dread decisions forced upon him in the position of king, he had had to suffer eighty thousand years in hell. Now he was destined to become king again in the same city, again to suffer the same fate. This was more than he could bear. As he wondered if escape was possible, a goddess dwelling in the umbrella above him, who had been his mother in a former life, spoke to him :

‘Temi my child, let me help you.

You must do as I advise : Pretend to be a crippled mute.

Don’t move your limbs or use your voice. Then the people will refuse to crown you king and you shall be free.’

The Bodhisatta at once began to show signs of being different from the other five hundred children. While the others cried out for their milk, Temiya did not utter a sound. For the first year, his mother and nurses noticed with alarm that he neither cried nor slept, moved nor listened, though his body appeared normal. Knowing that he must feel hunger, they tried to force a sound from him by withholding his milk, at times by starving him for a whole day, but to no avail. In his second year, they tempted him with various cakes and sweets over which the other children fought. But Temiya would say to himself : ‘Eat the cakes if you wish for hell’, and thus abstained. All kinds of foods, fruits, and toys left him unmoved, though other children grabbed greedily for them.

The Temiya Jataka -

The Temiya Jataka -

When Temiya (not shown in picture) was six years old, they set an elephant upon him, but Temiya unharmed and unmoved.

When he was five, they tried to terrify him into speaking. He was placed in the center of a house thatched with palm leaves. A servant was then ordered to set fire to it. Where normal children would have run away shrieking, the Bodhisatta remained motionless and sat quietly as the fire came closer to him, until he was taken away by his attendants. At six, they let an elephant loose at him ; at seven, they allowed serpents to coil about him. Still he remained unharmed and unmoved. In the following years, they showed him terrifying mimes, threatened him with swords, and made holes in four sides of a curtain around his bed and had conch players blast their sound through to him. They tried him with drums and sudden bright lamps in the middle of the night, but they failed to break his trance. Desperate, they covered him with molasses and allowed flies to cover and bite him, but he did not flinch. They forced him to remain unbathed, but his need for cleanliness did not overpower him. Pans of fire were placed under his bed, causing boils to break out on his body, but still he said to himself that hell was a hundred thousand times worse. His parents besought him to speak, to move, to listen, but he dared not.

At sixteen, when he would have been named heir apparent, they led him to a fumed chamber and tried to tempt him with beautiful maidens, but he stopped himself from breathing in order not to be weakened by the fragrances.

At last, the king summoned the soothsayers and asked them why at his son’s birth they had not mentioned any threatening signs of this affliction. Not understanding Temiya’s behavior but unwilling to admit their ignorance, they explained that they had not dared cast a shadow on the king’s joy when, after so many years, he had been given a son. But now, fearing for the safety of the country should an apparent idiot be named heir to the throne, they predicted dangers to the king’s life if Temiya were allowed to remain in the kingdom. Alerted by their words, the king asked what he should do. They advised him in this way: ‘You must yoke some horses to a chariot, send your son away in it, passing by the western gate, to a graveyard, and there he must be buried.’

When the queen heard of this plot, she knew the time had come to make the request which the king had promised years ago to grant. ‘Give the kingdom to my son’, she demanded. ‘For once he is crowned, he will certainly speak.’ The king protested. ‘Impossible, my Queen, for your son brings ill luck to us.’ Then give it to him for seven years’, she responded. Again the king refused. ‘Then for seven months’, she pleaded. ‘O Queen’, he said, ‘I dare not.’ “Then, alas, for seven days,” she sighed. “Very well.” The king relented. “Your wish is granted.”

And so it happened that Temiya was given the kingdom for seven days. He was led around the city, sometimes on an elephant, sometimes on men’s shoulders. Still he would not move either his limbs or his lips. On the seventh day, his mother begged him to speak, for on the day he was condemned to die. The Bodhisatta gravely considered her request, thinking to himself: “If I do not break my silence, my mother’s own heart will break ; if I do, I shall have wasted in one second what efforts I have made for sixteen years. Moreover, if I keep my pledge, my parents and I shall be saved from hell.”

Thus, Temiya again decided to be patient. For the day was near when he would be freed from the fear of inheriting the throne, and on that day, he would be able to speak. As the next morning dawned, the king gave his final orders to Sunanda the charioteer. “Yoke some horses to a chariot and set the prince in it. Take him out the western gate and find ground in which to dig a grave. After you have dug the hole, throw him into it and break his head with the back of your spade to kill him. Then scatter dust over him and make a heap of earth above. After bathing yourself, come back here.”

Sunanda took Temiya off, but though he thought he was passing through the western gate, the Death Gate, he did in fact drive to the eastern gate, which was the Victory Gate, and one of the chariot’s wheels struck the threshold. At the sound, the Bodhisatta knew he was on the threshold of attaining his freedom. By the power of the gods, a graveyard appeared. Sunanda stopped and removed Temiya’s royal ornaments from him, releasing him in one stroke from his yoke of royalty.

The Bodhisatta was at last freed from his vow, and as Sunanda worked at digging the grave, Temiya thought to himself, “In sixteen years, I have never moved my hands or feet. Can I do so now?” Whereupon he rose, rubbed his hands together, rubbed his feet with his hands, and alighted onto the ground, which at his touch became like a cushion filled with air. He then exercised his limbs by walking back and forth until he was satisfied that he had the strength he thought he had lost.

The Temiya Jataka -

The Temiya Jataka -

Temiya confirms his strenght by lifting a chariot.

This was his only chance to escape kingship and enter the forest as an ascetic, and the Bodhisatta wondered, was he powerful enough to overcome Sunanda if he tried to prevent his escape? As a final test of his strength, the Bodhisatta seized the back of the chariot and lifted it high with one hand as if it were a toy cart. Indeed, his power was confirmed. He walked over to the charioteer and tried to jolt him into looking at him with these words :

“Behold the man you seek to kill, not deaf nor dumb nor lame. Stop or bear the wrath of hell, for by this act you’ll die.”

Sunanda looked up but was so dazzled by the Bodhisatta’s beauty that he did not recognize him at first. Again Temiya identified himself. Suddenly Sunanda understood and fell at his feet, stammering that he would be honored to escort the prince home to inherit the kingdom. He who was destined for Buddhahood chided him, for nothing would deter him now from leading the pure meditative life. He described his previous existence and subsequent generations in hell and then ordered Sunanda to return to the palace immediately to tell his parents that he was still alive and thus spare them unnecessary grief over the loss of their only son.

As the charioteer approached the palace alone, the queen, who had been waiting by a window, saw him, assumed that her son was dead, and began to weep. But when Sunanda told her his story, she ceased. The king was told what his son had done, and he and the queen set out at once for the Victory Gate, hoping to lure the prince home.

Temiya has become an ascetic and lives in the forest. He preaches to his father, the King, who kneels before him.

Temiya has become an ascetic and lives in the forest. He preaches to his father, the King, who kneels before him.

When the long procession of horse-drawn carriages came to a halt, the royal pair found their son living in a hut of leaves prepared for him by Sakka. They saw that he had already put on an ascetic’s garments of red bark and leopard skin, a black antelope skin over one shoulder and a carrying pole over the other. His hair was tied up and matted, and he held a walking staff in one hand. Temiya welcomed them and explained to them the reasons for his sixteen years of self-denial. In awe of their son, they no longer begged him to wear the crown but were themselves inspired to embrace the holy life. Returning to the palace, the king ordered the royal treasure jars to be opened and the gold to be scattered about like sand. Sakka built for the entire kingdom a hermitage three leagues long, so that all who aspired to Nirvana could partake of the meditative life.

Mahajanaka Jataka

Mahajanaka Jataka.

Mahajanaka Jataka.

Prince Mahajanaka suffers a shipwreck. He struggles to keep alive swimming the ocean for 7 days untill the Gods came to rescue him. The scene symbolizes the virtue of Perseverance.

Wat Kongkaram, Ratchaburi

There was a king, Mahajanaka, of Mithila in the kingdom of Videha. He had two sons, Aritthajanaka and Polajanaka. When the old king died, the elder brother, Aritthajanaka, became king, and the younger brother his viceroy. In time the new king became suspicious of his brother’s popularity with the people and, fearful for his throne, had Polajanaka put in chains. But when Polajanaka proclaimed his innocence, miraculously his chains fell off and he was able to escape to a small village near the frontier of the kingdom. Since he was a strong leader, he attracted many followers.

In time he decided to take his revenge by declaring war on King Aritthajanaka. Before Aritthajanaka went to battle with his brother, he made his pregnant wife promise that should he be killed, she would flee from Mithila in order to protect the unborn child.

Scene from the Mahajanaka Jataka.

Scene from the Mahajanaka Jataka.

When she heard of the king’s death at the hand of his brother, Polajanaka, she gathered her gold and jewels into a basket and covered them with rice. She put on some worn and dirty garments and blackened her face with soot so that she would not be recognized. Then, lifting the basket onto her head, she went unnoticed out of the city by the northern gate. Now, the child in the fleeing queen’s womb was to be a Great Being, or Bodhisatta, and the attention of Sakka, king of the gods, was drawn to the queen’s plight. He therefore attired himself as an old man driving a carriage. On arriving at the queen’s side, he asked her where she was bound. She had in mind to go to the city of Kalacampa, sixty leagues away, but did not know the way. The disguised god offered to take her there, and after entering the carriage, the queen fell into a heavy sleep. By nightfall the carriage had reached the edge of Kalacampa. When the amazed queen asked how they could have reached the city so soon, Sakka told her that he had come by a straight road known only to the gods, then departed.

In Kalacampa, the unrecognized queen was observed by a northern Brahmin teacher of great fame. When he asked who she might be, she told him, “The chief queen of King Aritthajanaka of Mithila, lately killed in battle. I have come here in order to save the life of my unborn child.”

The Brahmin invited her to live in his house, saying that he would watch over her as if she were his younger sister. The queen agreed, and a short time later she gave birth to a son, whom she called after his grandfather Mahajanaka. He grew into a strong and sturdy child. However, he was often teased by his playmates and called “the widow’s son,” which name brought questions to his mind regarding his paternity. One day he went to his mother, threatening to bite off her breasts if she did not tell him who his father was. She was forced to reveal to him the secret of his birth-that he was the son of the former king of Mithila.

When the boy reached the age of sixteen, he determined to regain his father’s kingdom. He told his mother of his plan and she offered to give him her gold and jewels, which were sufficient to win back the kingdom. But he took only half of her gift, wishing to make his fortune in trade. She was alarmed for his safety, warning him of the dangers of the sea, but he was deaf to her words. After purchasing some goods for trading, he boarded a vessel bound for Suvannabhumi, the golden land of the east. On that day his uncle Polajanaka, king of Mithila, fell ill.

The Mahajanaka Jataka -

The Mahajanaka Jataka -

Mahajanaka suffers a shipwreck.

Crowded on board were the men and animals from seven large caravans. After seven days of plunging through the heavy seas at top speed, the overloaded ship began to founder. Planks broke off, and the water rose higher and higher. Mahajanaka, knowing that the ship was sinking, did not panic. He prepared himself for the ordeal by eating a full meal, covered himself with sugar and ghee to protect himself from the water, then tied himself to the mast. When the ship went down, men and animals were devoured by the sharks and fierce turtles that infested the ocean, but the mast remained upright. Mahajanaka with his superior strength was able to throw himself a far distance from the ship, thus escaping the fate of the other passengers. On that day Polajanaka died, leaving the throne of Mithila vacant.

The Mahajanaka Jataka -

The Mahajanaka Jataka -

Notice that the crew includes some foreigners, a common feature in Thai mural paintings.

Mahajanaka floated in the ocean for seven days, taking no food. During this time the goddess Manimekhala was enjoying the pleasures of heaven, neglecting her duties as guardian of the seas. At last she spied him and recognized that he was not an ordinary mortal. She took him in her arms, and Mahajanaka, thrilled by the touch of the goddess, fell into a trance. She flew with him to a mango grove in the kingdom of Mithila, where she laid him on his right side on a ceremonial stone in the middle of the grove.

The Mahajanaka Jataka -

The Mahajanaka Jataka -

Mahajanaka is saved by the Goddess Manimekhala.

From his deathbed, the king of Mithila had told his ministers that to find a man worthy of being king, they must look for one who could answer certain riddles, who could string the king’s powerful bow, and who could please his daughter, the beautiful and intelligent Princess Sivali. There were many candidates for the throne. Each one, in an effort to win Sivali, obeyed her every whim. The more they tried to please her, the more she scorned them and sent them away. Moreover, not one had the wit to answer the riddles or the strength to string the royal bow.

At last the ministers decided to send out the festive chariot to see if they could find a successor to Polajanaka. They decorated the city, yoked four noble steeds to the handsome carriage, and bade the musicians follow behind as is proper when a royal chariot is empty. Then they ordered the carriage to lead them to the one who had sufficient merit to be king of Mithila. Followed by a great crowd, it took them through the city to the eastern gate and onward to the park where Mahajanaka lay sleeping. After circling the stone, the chariot came to a stop. The ministers observed the sleeping prince and examined his feet, whereby they recognized the signs of royalty. Indeed, they saw that he was not only a future king but also destined to be emperor of four continents. They commanded the musicians to sound their instruments. At the noise, Mahajanaka awoke. Seeing all the people around him, he recognized that the white umbrella of kingship had come to him. He asked where the king might be. When told that he had died, he agreed to accept the kingdom.

Meanwhile, Princess Sivali was waiting. However, when the new king arrived he did not visit her or pay her any attention. One day when he was strolling in the garden, she could bear his indifference no longer. Running up to offer him her arm to lean on, she showed that he pleased her. Shortly thereafter she became his queen.

King Mahajanaka answered the riddles with ease. He was also able through his great strength to string the bow of King Polajanaka, so that he fulfilled all the conditions for becoming king. Wisely and well he ruled for seven thousand years. His wife Sivali bore him a son and heir to the throne.

One day the king was riding through his kingdom with his ministers when he observed two mango trees. The one that had been full of mangoes was broken and torn by the people who had come to pick the fruit, while the other, though barren, stood green and whole. Thus he came to understand that possessions bring only sorrow, and he determined to put aside his kingdom and take up the life of an ascetic. After shaving his head and putting on the robes of a hermit, he departed from the palace. But Queen Sivali, who loved him, followed him with great retinue. Wherever he went, she was behind him. At last he could bear it no longer. He cut a stalk of grass and said to her, “As this reed cannot be joined again, so you and I can never be joined again.”

At his words, Sivali fell down to earth. While the courtiers were attending to her, Mahajanaka disappeared into the forest. When the queen awoke, she could find him nowhere. He was never again seen in the world of men, for he found his way to the Himavat forest and eventually entered the Brahma heaven.

The despairing queen returned to Mithila and arranged for the coronation of her son. Having settled the affairs of the kingdom, she herself donned the robes of a hermit, and after many years she too was deemed worthy of entrance into the kingdom of the gods.

The Mahajanaka Jataka -

The Mahajanaka Jataka -

Mahajanaka looks up to his saviour, the Goddess Manimekhala.

Unless otherwise specified, all images from Wat Yai Intharam, Chonburi

Sama Jataka - Sama, the devoted Son

The Sama Jataka -

The Sama Jataka -

King Piliyakka

Two villages were situated on opposite banks of a river dividing the Kingdom of Benares. Their hunter chiefs, friends throughout the years, betrothed their infant children to each other shortly after their birth. Now, these two were not like other children. Both were born with skins of golden hue. And although they were surrounded by hunters, they refused to harm any living creature. They had a special destiny, for they had to replace with purity and goodness an evil carried with them from a former life. At that time, many lives ago, they had been born into the family of a doctor who, angered by a rich patient’s refusal to pay his fee for curing the eye disease, gave him some medicine which took away the sight of one eye. Though the evil was done by the head of the household, the children of the family also had to do penance. Thus it was that, once they were born into families of hunters and betrothed, they felt obliged to live as ascetics and deny themselves all pleasures of the senses. In vain each begged his parents to forgo the marriage. They were married against their will, but secretly determined to live as brother and sister.