Tipitaka

Tweets

अम्बेडकरवाद को दुबारा जीवित करना तभी किसी काम का है जब यह टिकाऊ रह सके।

To revive Ambedkarism is only worth if it can survive.

https://www.revolvy.com/main/index.php?s=Canon%20(music)&item_type=topic

Canon (music)

in 57) Classical Latin

LVII) Classical Latin, 58) Classical Latvian-Klasiskā latviešu valoda,59) Classical Lithuanian-klasikinis lietuvis,60) Classical Luxembourgish -Klassesch Lëtzebuergesch,61) Classical Macedonian-Класичен луксембуршки,62) Classical Malagasy-Malagasy,63) Classical Malay- Melayu Klasik,64) Classical Malayalam -ക്ലാസിക്കൽ മലയാളം,65) Classical Maltese- Klassiku Malti,

57) Classical Latin

LVII) Classical Latin Et

Tipitaka (Pali decem, “tria” + Pitaka: “canistra”), Pali sive Canon,

quae est collectum est Pali prima lingua texts, der in fundamenta

doctrinae formam ab Theravada Buddhismus. Pali paracanonical Tipitaka et in locis (commentariis Paralipomenon c) Theravada Classical Texts simul totum corpus. Canon enim est multitudo hominum Pali litterae: in Latina translatione textuum typis addere ad Milia ex pages. Maxime (sed non omnes) Canon ex har redan er editis Anglice super annis. Praesto sunt, non parva Selvom fraction of texts on this website disse, haec collectio potest esse bonus locus ut satus. Tipitaka tres partes sunt Vinaya Pitaka

A

collection of texts vedrørende morum normae esse dicuntur cotidie de

rebus ad gubernandum Recensiones in Sangha - the community of bhikkhus

(ordinavit monachis) et bhikkhunis (ordinavit nuns). Ut solum praecepta Dei plus quam quantum est album et de Vinaya Pitaka

også includit fabulis post originis uniuscuiusque regula prospiciens

illi a detailed propter quid bevare spørgsmålet Buddha solution duabus

communibus concordia inom diverse magna et communitas spiritualis.

Sutta Pitaka

Suttas collectio seu sermones usque tribuitur Buddha paucis proximis suis, praecipua continens doctrinae Theravada Buddhismus. (Latin sutta Plus quam mille unum sunt available in hac website.) Quod suttas fordelt quae in quinque nikayas (collections)

Digha Nikaya - in “collectio diu”

Majjhima Nikaya - in “medio-collectio longitudo ‘

Samyutta Nikaya - per “Ordinationem collectio”

Anguttara Nikaya - in “Further, factored collectio”

Khuddaka Nikaya - in “collectio modicae texts ‘;

Khuddakapatha

Dhammapada

Udana

Itivuttaka

Sutta Nipata

Vimanavatthu

Petavatthu

Theragatha

Therigatha

Jataka

Niddesa

Patisambhidamagga

Apadana

Buddhavamsa

Cariyapitaka

Nettippakarana (includitur in Burmese ex editione Tipitaka)

Petakopadesa ( “”)

Milindapañha ( “”) Abhidhamma Pitaka

A

collection of texts in som rationem ordinationemque Sutta Pitaka

Institutio doctrinalis, quae in eius compage som kan Applicata sint

descriptiones systematicas Reworked incomposita in investigatione usque

in en re et ratione mentis.

58) Classical Latvian

58) Klasiskā latviešu valoda Tipitaka

(Pali ti, “trīs”, “+ pitaka”, “grozi”) vai Pali canon ir primāro pali

valodu tekstu kolekcija, kas veido Theravada budisma doktrinālu pamatu. Tipitaka un Paracanonical Pali teksti (komentāri, hroniku utt.) Kopā veido pilnu ķermeņa klasisko Theravada tekstu. Pali canon ir plašs literatūras klāsts: tekstu angļu valodā tulkojot tūkstošiem drukātu lapu. Lielākā daļa (bet ne visas) no Canon jau gadu gaitā ir publicētas angļu valodā. Pielāgojiet tekstu, lai izveidotu tekstu, lai izveidotu tekstu, kas atbilst jūsu izvēlētajam tekstam. Tipitaka trīs nodaļas ir šādas: Vinaya Pitaka

Tekstu

krājums attiecībā uz rīcības noteikumiem, kas regulē ikdienas lietām

Sanghā - bhikhusa (ordinētu mūku) un bhikkunī (ordinētu mūķenēm)

kopienu. Nepārsniedzot noteikumu sarakstu, Vinaya Pitaka ietver arī stāstus par

katra likuma izcelsmi, sniedzot detalizētu pārskatu par Budas

risinājumu jautājumam par to, kā uzturēt kopīgo harmoniju lielā un

daudzveidīgā garīgā kopienā.

Sutta Pitaka

Būtas

un dažu viņa tuvāko mācekļu, kas satur visas galvenās mācības par

Theravada budismu, kolekcija ir saistīta vai diskutējama. (Vairāk nekā tūkstotis tulkojumu šajā mājas lapā ir pieejami.) Suttus tiek sadalīti starp pieciem niikajas (kolekcijas):

Digha Nikaya - “garā kolekcija”

Majjhima Nikaya - “vidēja garuma kolekcija”

Samjutta Nikaya - “sagrupētā kolekcija”

Anguttara Nikaya - “tālāk attīstīta kolekcija”

Khuddaka Nikaya - “mazo tekstu kolekcija”:

Khuddakapatha

Dhammapada

Udana

Itivuttaka

Sutta Nipata

Vimanavatthu

Petavatthu

Theragatha

Therigatha

jataka

Niddesa

Patisambhidamagga

Apadana

Buddhavamsa

Cariyapitaka

Nettakarana (iekļauta tikai Tiptaka birmiešu valodā)

Petakopadesa (”")

Milindapañha (”") Abhidhamma Pitaka

Jautājiet

par tekstu, kas saistīts ar pamatnoteikumiem, kas saistīti ar principu

un principu, un kas ir saistīts ar reorganizāciju un sistemātisku rammi,

kas ir saistīta ar zemu un zemu izmaksu pieaugumu.

In music, a canon is a contrapuntal (counterpoint-based) compositional technique that employs a melody with one or more imitations of the melody played after a given duration

(e.g., quarter rest, one measure, etc.). The initial melody is called

the leader (or dux), while the imitative melody, which is played in a

different voice, is called the follower (or comes). The follower must imitate the leader, either as an exact replication of its rhythms and intervals or some transformation thereof (see “Types of canon“, below). Repeating canons in which all voices are musically identical are called rounds—”Row, Row, Row Your Boat” and “Frère Jacques” are popular examples.

An accompanied canon is a canon accompanied by one or more additional independent parts that do not imitate the melody.

During the Middle Ages, Renaissance, and Baroque—that is, through the early 18th century—any kind of imitative musical counterpoints were called fugues, with the strict imitation now known as canon qualified as fuga ligata, meaning “fettered fugue” (Bridge 1881, 76; Mann, Wilson, and Urquhart n.d.; Walker 2000, 1). Only in the 16th century did the word “canon” begin to be used to describe the strict, imitative texture created by such a procedure (Mann, Wilson, and Urquhart n.d.). The word is derived from the Greek “κανών”, Latinised as canon, which means “law” or “norm”, and may be related to 8th century Byzantine hymns, or canons, like the Great Canon by St. Andrew of Crete.

In contrapuntal usage, the word refers to the “rule” explaining the

number of parts, places of entry, transposition, and so on, according to

which one or more additional parts may be derived from a single written

melodic line. This rule was usually given verbally, but could also be

supplemented by special signs in the score, sometimes themselves called

canoni (Bridge 1881, 76). The earliest known non-religious canons are English rounds, a form called rondellus, starting in the 14th century (Mann, Wilson, and Urquhart n.d.); the best known is Sumer Is Icumen In (composed around 1250), called a rota (”wheel”) in the manuscript source (Sanders 2001a; Sanders 2001b).

Canons featured in the music of the Italian Trecento and the 14th-century ars nova in France. An Italian example is Tosto che l’alba by Gherardello da Firenze.

In both France and Italy, canons were often used to illustrate hunting

songs. The Italian word for hunting is “caccia”, the Medieval French

word “chace” (modern spelling: “chasse”). A well-known French chace is

the anonymous Se je chant mains. Richard Taruskin (2010,

331) describes Se je chant mains as evoking the atmosphere of a falcon

hunt: “The middle section is truly a tour de force, but of a wholly new

and off-beat type: a riot of hockets set to ‘words’ mixing French,

bird-language, and hound-language in an onomatopoetical mélange.” Guillaume de Machaut

also used the 3-voice “chace” form in movements from his masterpiece Le

Lai de la Fontaine (1361). Referring to the setting of the fourth

stanza of this work, Taruskin (2010, 334–35) describes it as, “Harmony in the most literal, etymological sense. Like the Trinity

itself, a well-wrought chace can be far more than the sum of its parts;

and this particular chace is possible Machaut’s greatest feat of

subtilitas.”

An example of late 14th century canon which featured some of the rhythmic complexity of the late 14th century ars subtilior school of composers is La Harpe de melodie by Jacob de Senleches

In

many pieces in three contrapuntal parts, only two of the voices are in

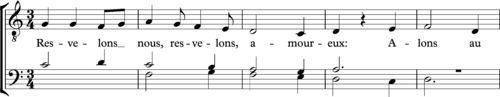

canon, while the remaining voice is a free melodic line. In Dufay’s song “Resvelons nous, amoureux”, the lower two voices are in canon, but the upper part is what David Fallows (1982, 89) describes as a “florid top line”:

Both J.S. Bach and Handel featured canons in their works. The final variation of Handel’s keyboard Chaconne in G major (HWV

442) is a canon in which the player’s right hand is imitated at the

distance of one beat, creating rhythmic ambiguity within the prevailing

triple time:

An example of a classical strict canon is the Minuet of Haydn’s String Quartet in D Minor, Op. 76, No. 2 (White 1976, 66):

Beethoven’s works feature a number of passages in canon. The following comes from his Symphony No. 4:

Antony Hopkins (1981,

108) describes the above as “a delightfully naïve canon”. More

sophisticated and varied in its treatment of intervals and harmonic

implications is the canonic passage from the second movement of his

Piano Sonata 28 in A major, Op. 101:

An even subtler example comes from Beethoven’s Piano Sonata 29. Wilfrid Mellers (1982, 176) describes the trio section of the scherzo

movement as “mysterious”, with a metrical ambiguity that “makes the

melodic phrases irregular.” When the tune is repeated, it is “now in the

left hand, [with] the flowing triplets in the right… in canon with

the bass line.” Mellers concludes: “Here contrapuntal oneness serves to

control any airy floating in the tune’s asymmetry: it is not merely the

wide-spread texture that sounds hollow, almost forlorn.”

[1]:

In

the Romantic era, the use of devices such as canon was even more often

subtly hidden, as for example in Schumann’s piano piece “Vogel als

Prophete” (1851).

According to Nicholas Cook (1990,

164), “the canon is, as it were, absorbed into the texture of the

music—it is there, but one doesn’t easily hear it.” Even more elusive is

the following passage from Brahms’ Intermezzo in F minor, Op. 118 No. 4, where the left hand shadows the right at the time distance of one beat and at the pitch interval of an octave lower:

Michael Musgrave (1985,

262) writes that as a result of the strict canon at the octave, the

piece is “of an anxious, suppressed nature, […] in the central section

this tension is temporarily eased through a very contained passage

which employs the canon in chordal terms between the hands.”

Considering

the many types of canon “in the tonal repertoire”, it may be ironic

that “canon—the strictest type of imitation—has such a wide variety of

possibilities” (Davidian 2015,

136). The most rigid and ingenious forms of canon are not strictly

concerned with pattern but also with content. Canons are classified by

various traits including the number of voices, the interval at which

each successive voice is transposed in relation to the preceding voice,

whether voices are inverse, retrograde, or retrograde-inverse;

the temporal distance between each voice, whether the intervals of the

second voice are exactly those of the original or if they are adjusted

to fit the diatonic scale, and the tempo of successive voices. However, canons may use more than one of the above methods.

Although,

for clarity, this article uses leader and follower(s) to denote the

leading voice in a canon and those that imitate it, musicological

literature also uses the traditional Latin terms dux and comes for “leader” and “follower”, respectively.

A

canon of two voices may be called a canon in two, similarly a canon of x

voices would be called a canon in x. This terminology may be used in

combination with a similar terminology for the interval between each

voice, different from the terminology in the following paragraph.

Another

standard designation is “Canon: Two in One”, which means two voices in

one canon. “Canon: Four in Two” means four voices with two simultaneous

canons. While “Canon: Six in Three” means six voices with three

simultaneous canons, and so on.

A simple canon (also known as a round) imitates the leader perfectly at the octave or unison. Well-known canons of this type include the famous children’s songs Row, Row, Row Your Boat and Frère Jacques.

If

the follower imitates the precise interval quality of the leader, then

it is called a strict canon; if the follower imitates the interval

number (but not the quality—e.g., a major third may become a minor third), it is called a free canon (Kennedy 1994).

The follower is by definition a contrapuntal derivation of the leader.

An inversion canon (also called an al rovescio canon) has the follower moving in contrary motion to the leader. Where the leader would go down by a particular interval, the follower goes up by that same interval (Kennedy 1994).

In a retrograde canon, also known as a canon cancrizans (Latin for crab canon,

derived from the Latin cancer = crab), the follower accompanies the

leader backward (in retrograde). Alternative names for this type are

canon per recte et retro or canon per rectus et inversus (Kennedy 1994).

In a mensuration canon (also known as a prolation canon,

or a proportional canon), the follower imitates the leader by some

rhythmic proportion. The follower may double the rhythmic values of the

leader (augmentation or sloth canon) or it may cut the rhythmic

proportions in half (diminution canon). Phasing

involves the application of modulating rhythmic proportions according

to a sliding scale. The cancrizans, and often the mensuration canon,

take exception to the rule that the follower must start later than the

leader; that is, in a typical canon, a follower cannot come before the

leader (for then the labels ‘leader’ and ‘follower’ should be reversed)

or at the same time as the leader (for then two lines together would

constantly be in unison, or parallel thirds, etc., and there would be no

counterpoint), whereas in a crab canon or mensuration canon the two

lines can start at the same time and still respect good counterpoint.

Many such canons were composed during the Renaissance, particularly in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries; Johannes Ockeghem wrote an entire mass (the Missa prolationum) in which each section is a mensuration canon, and all at different speeds and entry intervals. In the 20th century, Conlon Nancarrow composed complex tempo or mensural canons, mostly for the player piano as they are extremely difficult to play. Larry Polansky has an album of mensuration canons, Four-Voice Canons. Arvo Pärt has written several mensuration canons, including Cantus in Memoriam Benjamin Britten, Arbos and Festina Lente. Per Nørgård’s infinity series has a sloth canon structure (Mortensen n.d.). This self-similarity of sloth canons makes it “fractal like” and the same idea is explored in Fractal Tune Smithy’s Sloth Canons

The most familiar of the canons is the perpetual/infinite canon (in Latin: canon perpetuus) or round. As each voice of the canon arrives at its end it can begin again, in a perpetuum mobile fashion; e.g., “Three Blind Mice”. Such a canon is also called a round or, in medieval Latin terminology, a rota. Sumer is icumen in is one example of a piece designated rota.

Additional

types include the spiral canon, accompanied canon, and double or triple

canon. A double canon is a canon with two simultaneous themes, a triple canon has three.

In a mirror canon

(or canon by contrary motion), the subsequent voice imitates the

initial voice in inversion. They are not very common, though examples of

mirror canons can be found in the works of Bach, Mozart (e.g., the trio

from Serenade for Wind Octet in C, K. 388), Webern, and other

composers.

|

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. |

|

A Table canon is a retrograde and inverse

canon meant to be placed on a table in between two musicians, who both

read the same line of music in opposite directions. As both parts are

included in each single line, a second line is not needed. Bach wrote a few table canons (Benjamin 2003, 120).

Olivier Messiaen

employed a technique which he called “rhythmic canon”, a polyphony of

independent strands in which the pitch material differs. An example is

found in the piano part of the first of the Trois petites liturgies de la présence divine, where the left hand (doubled by strings and maracas), and the right hand (doubled by vibraphone)

play the same rhythmic sequence in a 3:2 ratio, but the right hand

adapts a sequence of 13 chords in the sixth mode (B-C-D-E-F-F-G-A-B)

onto the 18 duration values, while the left hand twice states nine

chords in the third mode (Griffiths 2001). Peter Maxwell Davies was another post-tonal composer who favoured rhythmic canons, where the pitch materials are not obliged to correspond (Scholes, Nagley, and Whittall n.d.).

A

puzzle canon, riddle canon, or enigma canon is a canon in which only

one voice is notated and the rules for determining the remaining parts

and the time intervals of their entrances must be guessed (Merriam-Webster).

“The enigmatical character of a [puzzle] canon does not consist of any

special way of composing it, but only of the method of writing it down,

of which a solution is required” (Richter 1888, 38). Clues hinting at the solution may be provided by the composer, in which case the term “riddle canon” can be used (Scholes, Nagley, and Whittall n.d.). J S Bach presented many of his canons in this form, for example in The Musical Offering. Mozart, after solving Father Martini’s puzzles (Zaslaw and Cowdery 1990,

98), composed his own riddles using Latin epigrams such as “Sit trium

series una” and “Ter ternis canite vocibus” (”Let there be one series of

three parts” and “sing three times with three voices”) (Karhausen 2011, 151).

Other notable contributors to the genre include Ciconia, Ockeghem, Byrd, Beethoven, Brumel; Busnois, Haydn, Josquin des Prez, Mendelssohn, Pierre de la Rue, Brahms, Schoenberg, Nono and Maxwell Davies (Carvalho 1999, 38–39; Davidian 2015, 136; Davies 1971; Davies 1972; Hartmann 1989, passim; Hewett 1957, passim; Johnson 1994, 162–63; Jones 2009, 152; Leven 1948, 361 Litterick 2000, 388; Mann, Wilson, and Urquhart n.d.; Morley 1597, 173, 176; Perkins 2001; Tatlow 1991, 15, 126; Todd 2003, 165; van Rij 2006, 215; Watkins 1986, 239). According to Oliver B. Ellsworth, the earliest known enigma canon appears to be an anonymous ballade, En la maison Dedalus,

found at the end of a collection of five theory treatises from the

third quarter of the fourteenth century collected in the Berkeley

Manuscript (Ciconia 1993, 411n12).

Thomas Morley complained that sometimes a solution, “which being founde (it might bee) was scant worth the hearing” (Morley 1597, 104, cited, inter al., by Barrett 2014, 123). J. G. Albrechtsberger admits that, “when we have traced the secret, we have gained but little; as the proverb says, ‘Parturiunt montes, etc.‘” but adds that, “these speculative passages…serve to sharpen acumen” (Albrechtsberger 1855, 234).

- Josquin des Prez,

Missa L’homme armé super voces musicales, Agnus Dei 2: One voice with

the words ‘ex una voce tres’ (three voice parts out of one), a

mensuration canon in three voices. - Josquin

des Prez, Missa L’homme armé sexti toni, Agnus Dei 2: two simultaneous

canons in the four upper voices, and at the same time a crab canon in

the two lower voices. - Johann Sebastian Bach’s Goldberg Variations contains nine canons of increasing interval size, ranging from unison to ninth. Each canon additionally obeys the overall structure and harmonic sequence common to all variations in the composition.

In his early work, such as Piano Phase (1967) and Clapping Music (1972), Steve Reich used a process he calls phasing

which is a “continually adjusting” canon with variable distance between

the voices, in which melodic and harmonic elements are not important,

but rely simply on the time intervals of imitation (Mann, Wilson, and Urquhart n.d.).

- Pachelbel’s Canon

- Canon, a 1964 animated representation of a musical canon

- Albrechtsberger,

Johann Georg. 1855. J.G. Albrechtsberger’s Collected Writings on

Thorough-bass, Harmony, and Composition, for Self Instruction, edited by

Sabilla Novello, translated by Ignaz von Seyfried, revised by Vincent Novello. London: Novello, Ewer, & Company. [ISBN unspecified]. - Barrett, Margaret S. (ed.). 2014. Collaborative Creative Thought and Practice in Music. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 9781472415868.

- Benjamin, Thomas. 2003. The Craft of Tonal Counterpoint New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-94391-4 (accessed 14 April 2011)

- Bridge, J. Frederick. [1881]. Double Counterpoint and Canon. London: Novello & Co., Ltd.; New York: The H. W. Gray Co., Inc.

- Carvalho,

Mário Vieira de. 1999. “Towards Dialectic Listening: Quotation and

Montage in the Work of Luigi Nono”. Contemporary Music Review 18, no 2:

37–85. - Ciconia,

Johannes. 1993. Nova musica and De Proportionibus, edited and

translated by Oliver B. Ellsworth. Greek and Latin Music Theory 9.

Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803214651. - Cook, Nicolas. 1990. Music, Imagination and Culture. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press.

- Cooper, Martin. 1970. Beethoven: The Last Decade. London and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Davidian,

Teresa. 2015. Tonal Counterpoint for the 21st-Century Musician: An

Introduction. Lanham and London: Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-3458-1 (cloth); ISBN 978-1-4422-3459-8 (pbk); ISBN 978-1-4422-3460-4 (ebook). - Davies,

Peter Maxwell. 1971. “Canon: In Mem. IS”. Tempo 97 (June):

[Supplement]: In Memoriam: Igor Fedorovich Stravinsky. Canons and

Epitaphs, Set I: one unnumbered page. - Davies,

Peter Maxwell. 1972. [Supplement]: “Canons and Epitaphs in Memoriam

Igor Stravinsky. A Solution by Peter Maxwell Davies of the Puzzle-Canon

He Contributed to Set I, Published in Tempo 97″. Tempo, no. 100: three

unnumbered pages. - Griffiths,

Paul. 2001. “Messiaen, Olivier (Eugène Prosper Charles)”. The New Grove

Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers. - Hartmann,

Günter. 1989. “Ein Albumblatt für Eliza Wesley: Fragen zu Mendelssohns

Englandauenthalt 1837 und eine spekulative Antwort”. Neue Zeitschrift

für Musik 150, no. 1:10–14. - Hewett,

Helen. 1957. “The Two Puzzle Canons in Busnois’s Maintes femmes”.

Journal of the American Musicological Society 10, no. 2 (Summer):

104–10. - Hopkins, Antony. 1981. The Nine Symphonies of Beethoven. London: Heinemann.

- Johnson, Stephen. 1994. Beethoven. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780671887896.

- Jones, David Wyn. 2009. The Life of Haydn. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89574-3 (cloth); ISBN 978-1-107-61081-1 (pbk).

- Karhausen, Lucien. 2011. The Bleeding of Mozart. Xlibris. ISBN 9781456850760.

- Kennedy,

Michael (ed.). 1994. “Canon”. The Oxford Dictionary of Music, associate

editor, Joyce Bourne. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-869162-9. - Leven, Louise W. 1948. “An Unpublished Mendelssohn Manuscript”. The Musical Times 89, no. 1270 (December): 361–63.

- Litterick,

Louise. 2000. “Chansons for Three and Four Voices”. In The Josquin

Companion, edited by Richard Sherr, 335–92. Oxford and New York: Oxford

University Press. ISBN 0-19-816335-5. - Mann,

Alfred, J. Kenneth Wilson, and Peter Urquhart. n.d. “Canon (i)”. Grove

Music Online. Oxford Music Online (Accessed 2 January 2011) (subscription required). - Mellers, Wilfred. 1983. Beethoven and the Voice of God. London: Faber and Faber.

- Merriam-Webster. n.d. “Puzzle Canon“”. Merriam-Webster Dictionary online edition (subscription required).

- Morley, Thomas. 1597. A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke, Set Downe in Forme of a Dialogue. London: Peter Short. [ISBN unspecified]

- Mortensen, Jørgen. n.d. “The ‘Open Hierarchies’ of the Infinity Series“.

In Per Nørgård: En introduktion til komponisten og hans musik (Danish

and English), edited by Jørgen Mortensen. www.pernoergaard.dk (Accessed

20 January 2013). - Musgrave, Michael. 1985. The Music of Brahms. London: Routledge.

- Perkins,

Leeman L. 2001. “Ockeghem [Okeghem, Hocquegam, Okegus etc.], Jean de

[Johannes, Jehan]”. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians,

second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London:

Macmillan Publishers. - Richter, Ernst Friedrich. 1888. A Treatise on Canon and Fugue: Including the Study of Imitation. Boston: Oliver Ditson. Translated from third German edition by Foote, Arthur W. [ISBN unspecified].

- Sanders,

Ernest H. 2001a. “Rota”. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and

Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell.

London: Macmillan Publishers. - Sanders,

Ernest H. 2001b. “Sumer is icumen in”. The New Grove Dictionary of

Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John

Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers. - Scholes,

Percy, Judith Nagley, and Arnold Whittall. “Canon”. The Oxford

Companion to Music, edited by Alison Latham. Oxford Music Online. Oxford

University Press (accessed 13 December 2014) (subscription required). - Taruskin,

Richard. 2010. Music from the Earliest Notations to the Sixteenth

Century: The Oxford History of Western Music, Volume 1. Oxford and New

York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-538481-9. - Tatlow, Ruth. 1991. Bach and the Riddle of the Number Alphabet. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36191-0.

- Todd, R. Larry. 2003. Mendelssohn. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-511043-2.

- van Rij, Inge. 2006. Brahms’s Song Collections. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83558-9.

- Walker,

Paul Mark. 2000. Theories of Fugue from the Age of Josquin to the Age

of Bach. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press. ISBN 9781580461504. - Watkins,

Glenn. 1986. “Canon and Stravinsky’s Late Style”. In Confronting

Stravinsky: Man, Musician, and Modernist, edited by Jann Pasler, 217–46.

Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05403-2. - White, John David. 1976. The Analysis of Music. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-033233-X.

- Zaslaw,

Neal, and William Cowdery (eds.) 1990. The Compleat Mozart: A Guide to

the Musical Works of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. New York: W. W. Norton

& Company. ISBN 9780393028867.

- Agon,

Carlos, and Moreno Andreatta. 2011. “Modeling and Implementing Tiling

Rhythmic Canons in the OpenMusic Visual Programming Language”.

Perspectives of New Music 49, no. 2 (Summer): 66–91. - Amiot,

Emmanuel. “Structures, Algorithms, and Algebraic Tools for Rhythmic

Canons”. Perspectives of New Music 49, no. 2 (Summer): 93–142. - Andreatta,

Moreno. 2011. “Constructing and Formalizing Tiling Rhythmic Canons: A

Historical Survey of a ‘Mathematical’ Problem”. Perspectives of New

Music 49, no. 2 (Summer): 33–64. - Blackburn,

Bonnie J. 2012. “The Corruption of One Is the Generation of the Other:

Interpreting Canonic Riddles”. Journal of the Alamire Foundation 4, no. 2

(October):182–203. - Davalan, Jean-Paul. 2011. “Perfect Rhythmic Tiling”. Perspectives of New Music 49, no. 2 (Summer): 144–97.

- Johnson, Tom. 2011. “Tiling in My Music”. Perspectives of New Music 49, no. 2 (Summer): 9–21.

- Lamla, Michael. 2003 Kanonkünste im barocken Italien, insbesondere in Rom. 3 vols. Berlin: Dissertation.de—Verlag im Internet. ISBN 3-89825-556-5.

- Lévy, Fabien. 2011. “Three Uses of Vuza Canons”. Perspectives of New Music 49, no. 2 (Summer): 23–31.

- Messiaen,

Olivier. Traité de rythme, de couleur, et d’ornithologie (1949–1992).

I-II, edited by Yvonne Loriod, preface by Pierre Boulez. Paris: Leduc,

1994. - Schiltz,

Katelijne, and Bonnie J. Blackburne (eds.). 2007. Canons and Canonic

Techniques, 14th–16th Centuries: Theory, Practice, and Reception

History. Proceedings of the International Conference Leuven, 4–5 October

2005. Analysis in Context: Leuven Studies in Musicology 1. Leuven and

Dudley, Massachusetts: Peeters. ISBN 978-90-429-1681-4. - Vuza,

Dan Tudor. 1991–93. “Supplementary Sets and Regular Complementary

Unending Canons”, in four parts. Perspectives of New Music 29, no. 2

(Summer 1991): 22–49; 30, no. 1 (Winter): 184–207; 30, no. 2 (Summer,

1992): 102–25; 31, no. 1 (Winter 1993): 270–305. - Ziehn,

Bernhard. Canonic Studies: A New Technique in Composition, edited and

introduced by Ronald Stevenson. New York: Crescendo Pub., 1977. ISBN 0-87597-106-7.

- Anatomy of a Canon

- The Musical Offering –A Musical Pedagogical Workshop by J.S. Bach, or, The Musical Geometry of Bach’s Puzzle Canons

- Visualization of J. S. Bach’s crab canon

- Software SonneLematine to produce canons

- Electro-Acoustic Music Dartmouth.edu: Larry Polansky’s Four Voice Canons

- Watch Canon, a film by Norman McLaren at NFB.ca

- Video Canon (My Favorite Things)

- Animated graphical scores of canons by Pachelbel, Bach, et al.

59) Classical Lithuanian

59) klasikinis lietuvis

“Tipitaka”

(”pali ti”, “trys”, “pitaka”, “krepšeliai”) arba “Pali canon” yra

pirminių pali kalbos tekstų rinkinys, sudarantis Theravada budizmo

doktrininį pagrindą. Tipitaka ir parakanoninis Pali tekstas (komentarai, kronikos ir kt.) Kartu sudaro visą klasikinių Theravada tekstų kūną.

“Pali canon” yra didžiulis literatūros sąrašas: vertimuose anglų kalba tekstai susideda iš tūkstančių spausdintų puslapių. Dauguma (bet ne visos) “Canon” jau seniai buvo paskelbtos anglų kalba. Selv om kun et lille del af disse tekster er tilgængelige på denne hjemmeside, kan denne samling være et godt sted at starte.

Trys Tipitaka padaliniai yra:

Vinaya Pitaka

Tekstų

rinkinys, susijęs su elgesio taisyklėmis, reguliuojančiomis kasdienius

reikalus Sanghoje - bhikkhus bendruomenės (šventųjų vienuolių) ir

bhikkūnų (ordinuojamų vienuolių). Virš taisyklių sąrašo Vinaya Pitaka taip pat apima pasakojimus apie

kiekvienos taisyklės kilmę, išsamiai aprašydama Budos sprendimą, kaip

išlaikyti bendruomeninę harmoniją didelėje ir įvairioje dvasinėje

bendruomenėje.

Sutta Pitaka

Susčių

ar diskursų rinkinys priskiriamas Budai ir keletui jo artimiausių

mokinių, kuriuose yra visi pagrindiniai Theravada budizmo mokymai. (Šioje svetainėje galima rasti daugiau nei tūkstantį vertimų.) Suttos yra suskirstytos į penkias nikayas (rinkinius):

“Digha Nikaya” - “ilgoji kolekcija”

Majjhima Nikaya - “vidutinio ilgio kolekcija”

Samyutta Nikaya - “sugrupuota kolekcija”

Anguttara Nikaya - “tolesnė fokusuota kolekcija”

Khuddaka Nikaya - “mažų tekstų rinkinys”:

Khuddakapatha

Dhammapada

Udana

Itivuttaka

Sutta Nipata

Vimanavatthu

Petavatthu

Theragatha

Therigatha

jataka

Niddesa

Patisambhidamagga

Apadana

Buddhavamsa

Cariyapitaka

Nettakarana (įtraukta tik į Birmos Tipitaka leidimą)

Petakopadesa (”")

Milindapañha (”")

Abhidhamma Pitaka

Pasirodžius

tekstui, vadovaujantis pagrindine doktrinære principene ir Sutta

Pitaka, rebarejdet ir reorganizuojant i sistemingai ramme, galiu

susipażinti su nepakankamumu ir nusiunćia jus nuo smalsumo.

60) Classical Luxembourgish

60) Klassesch Lëtzebuergesch

D’Tipitaka

(Pali ti, “dräi,” + pitaka, “Kuerf”) oder Pali kanon, ass d’Sammlung

primär Pali Sproochexter, déi d’Doctrinalstëftung vum Theravada

Buddhismus bilden. D’Tipitaka an d’Paracanonical Pali Texter (Kommentaren, Chroniken,

etc.) bilden déi komplett Kierper vun klassesch Theravada Texter.

De

Pali kanon ass eng riesech Kierper vun der Literatur: Bei der

englescher Iwwersetzung sinn déi Texter op d’Dausende vu gedréckte

Säiten eropzelueden. Déi meescht (awer net alles) vum Canon ass scho laang an Englesch publizéiert. Selwë ka Kun eng Lille vun dësem Text opzemaachen op dës Homepage, kann dës Sammlunge vläit e gudde Stéck opgoen.

Déi dräi Divisioune vun der Tipitaka ginn:

Vinaya Pitaka

D’Sammlung

vu Texter iwwer d’Regelen vum Behuelen, deen de deeglechen Affären am

Sangha - d’Gemeinschaft vu bhikkhus (geweihte Mönche) an bhikkhunis

(Offline Nonnen) regéiert. Vill méi wéi d’Lëscht vun de Regelen ass d’Vinaya Pitaka och

d’Geschichten hannert dem Urspronk vun all Reglement. Dee detailéierte

Rechnung iwwer d’Buddha-Léisung op d’Fro stellt wéi d’Kommunistesch

Harmonie innerhalb enger grousser a diverser geeschtlecher Gemeinschaft

beibehale gëtt.

Sutta Pitaka

D’Sammlung

vu Suttas oder Diskussiounen, déi de Buddha a puer vu sengen Jénger

zouginn huet, déi all déi zentrale Léierin vum Theravada Buddhismus

enthalen. (Méi wéi dausend Iwwersetzunge sinn op dëser Websäit verfügbar.) D’Suttë ginn ënnert 5 Niwwelen (Sammlungen) gedeelt:

Digha Nikaya - déi “laang Kollektioun”

Majjhima Nikaya - d’”mëttlere Kollektioun”

Samyutta Nikaya - déi “Gruppéierter Collectioun”

Anguttara Nikaya - d’”weider Faktore Sammlung”

Khuddaka Nikaya - d’”Sammlung vu kleng Texter”:

Khuddakapatha

Dhammapada

Udana

Itivuttaka

Sutta Nipata

Vimanavatthu

Petavatthu

Theragatha

Therigatha

jataka

Niddesa

Patisambhidamagga

APADANA

Buddhavamsa

Cariyapitaka

Nettakarana (nëmmen an der birmanescher Editioun vum Tipitaka)

Petakopadesa (”")

Milindapañha (”")

Abhidhamma Pitaka

De

Sammelstil vun der Zeechnung, wéi d’ënnersträicht Doktrinære Prinzipien

a Sutta Pitaka erbaut a rekonstituéiert an en systematesche Rama, sou

datt et an engem Ënnersichel an d’Naturen vu Sons a Malerei anzesetzen.

61) Classical Macedonian

61) Класичен луксембуршки

Типитака

(Пали ти, “три”, + питака, “кошници”) или пали канон е збирката на

примарни текстови на пали јазик кои ја формираат доктрината основа на

Теравадата будизмот. Тектиката и Паракононичките пали текстови (коментари, хроники, итн.)

Заедно го сочинуваат целото тело на класичните текстови Теравада.

Палискиот канон е огромно тело на литература: во преводот на англиски, текстовите содржат илјадници печатени страници. Повеќето (но не сите) на Канон веќе биле објавени на англиски јазик со текот на годините. Доколку сакате да го направите тоа, можете да ги најдете на почеток, за да може да започнете со работа.

Три одделенија на Tipitaka се:

Винаја Питака

Збирката

на текстови во врска со правилата на однесување кои ги регулираат

секојдневните работи во рамките на сангха - заедницата на бихикус

(ракоположени монаси) и бихикуни (ракоположен калуѓерки). Многу повеќе отколку само листа на правила, Vinaya Pitaka også

вклучува приказни зад потеклото на секоја власт, Обезбедување на детална

сметка за решение на две spørgsmålet на Буда како bevare комунални

хармонија inom голема и разновидна духовна заедница.

Sutta Pitaka

Збирката

на сутати, или дискурси, му се припишува на Буда и на неколку негови

најблиски ученици, ги содржат сите централни учења на Теравада будизмот.

(Повеќе од илјада преводи се достапни на оваа веб-страница.) Сутите се поделени меѓу пет нијакаи (збирки):

Дига Никаја - “долгата колекција”

Мајџхима Никаја - “колекција од средна должина”

Самутта Никаја - “групирана колекција”

Anguttara Nikaya - “натамошна колекција”

Khuddaka Nikaya - “колекција на мали текстови”:

Khuddakapatha

Dhammapada

Udana

Itivuttaka

Sutta Nipata

Vimanavatthu

Petavatthu

Theragatha

Therigatha

jataka

Niddesa

Patisambhidamagga

Apadana

Buddhavamsa

Cariyapitaka

Nettakarana (вклучени само во бурманскиот издание на Tipitaka)

Petakopadesa ( “”)

Milindapañha (”")

Abhidhamma Pitaka

Собирањето

на текстови во som основните принципи Доктрината презентирани во Сута

Pitaka се преработил и реорганизирана во систематско рамка som кан

Применета сусам en истрага за природата на умот и материјата.

http://secularbuddhism.org/2012/10/22/the-buddhas-manifesto-on-miracles-and-revelation/

The Buddha’s Manifesto on Miracles and Revelation

The Kevaddha Sutta* (Dīgha Nikāya

11) opens with Kevaddha, a householder, who tells the Buddha that there

are many potential converts to the Buddha dhamma living nearby in

Nāḷandā. He suggests that the Buddha get one of his monks to use

miracles to excite and amaze them. This would, he says, be sure to gain

many new adherents.

But the Buddha does not assent:

Kevaddha, this is not the way I teach Dhamma to the

monks, by saying: “Go, monks, and perform superhuman feats and miracles

for the white-clothed laypeople!” (1)

Pressed by Kevaddha, the Buddha clarifies himself. He says he

recognizes just three forms of miracle: certain psychic powers,

telepathic mind reading, and instruction in the dhamma. However, he is

only willing to countenance the “miracle of instruction” in the dhamma

when it comes to attracting new adherents.

Against Miracles

The Buddha gives an argument as to why he does not accept using the

two real kinds of miracle, psychic powers and telepathy. While he

recognizes them as real, he also recognizes that they will not convince

the skeptic. The Buddha says that there are certain charms (the Gandhāra

and Maṇika charms, in particular) that are reputed to give one

miraculous powers, and so any skeptic who sees such powers will

attribute them to the work of a charm rather than to the abilities of

the person performing the miracle. If so, of course, the skeptic will

not be convinced that the miracle worker is one with true wisdom.

For this reason, the Buddha says, using psychic powers and telepathy

are not good ways to bring new adherents. “And that is why, Kevaddha,

seeing the danger of such miracles, I dislike, reject and despise them.”

(5)

Now, there are several things one can say about the Buddha’s

argument. The translator, Maurice Walshe, claims that the skeptic’s

position is weak: he or she “does not have a really convincing way of

explaining things away. Modern parallels suggest themselves.” (p.

557n.235). In other words, there is little reason to accept the

existence of the Gandhāra and Maṇika charms, and so the Buddha’s skeptic

would only be dismissing these miracles in an ad hoc fashion. Walshe apparently believes modern skeptics follow the same pattern.

But I don’t think this is an adequate interpretation of the passage.

For one, Kevaddha also appears familiar with the existence of the

Gandhāra and Maṇika charms, and there is no independent reason for

supposing either he or the Buddha believed them ineffective. If so, then

the skeptic’s argument would have been convincing at the time, if not

to a modern ear.

But to go deeper, why should the Buddha care if some skeptic might

misconstrue the source of this miraculous power? Surely many in a large

audience would be convinced by such marvels as becoming invisible,

walking on water, or flying through the air, to take three of the

abilities that fall under the Buddha’s conception of “psychic power”.

Surely many would accept the Buddha as a powerful, knowledgeable

teacher, even if some skeptics were left to one side. So it is perhaps

more accurate to say that the Buddha doesn’t have a convincing way of

explaining why he should not use miraculous powers, if they are

available to him. Or at least he doesn’t present a very convincing

argument in the sutta.

So what is really going on here? Two possible explanations come to

mind. The first is what the Buddha may have wanted to get across to

Kevaddha, the second is a bit subtler.

Perhaps the Buddha is really saying that these miracles don’t bring

people to the dhamma for the right reasons. They are mere circus show;

the sorts of things that stun and delight the crowd but don’t really

instruct. Thus their contrast with the so-called “miracle of

instruction”. In effect, the miracles are but sense delights; the sorts

of things that lead to attachment and craving. The real miracle is not

supernatural at all. It is the ‘miracle’ of the dhamma: of teaching true

wisdom.

The second explanation is that the Buddha may have known that his

miraculous powers were largely or wholly internal and subjective:

thoughts and images in states of deep meditation, instead of actual

invisibility; subtle demonstrations open to interpretation, unlikely to

sway the unconvinced. If so, it’s not only a few crafty skeptics who

would have been unmoved, since powers such as becoming invisible,

walking on water, or flying through the air would not have been publicly

available, or at least not in a way likely to dazzle the householders.

And it is all too easy for a smart cross-examiner, such as those

“hair-splitting marksmen” mentioned in the Cūḷahatthipadopama Sutta, to unmask apparent examples of telepathy.

The dhamma, on the other hand, is publicly explicable, hard to find fault with, and more likely to convince.

If this is the correct reading, then the Buddha was right to abjure miraculous folderol and stick to true instruction.

Brahmā Behind the Curtain

The second part of the Kevaddha Sutta contains one of the

great satires of the ancient world. Here the Buddha speaks about “a

certain monk” of his order who wanted to know “where the four great

elements … cease without remainder.” He had meditative capacities that

gave him access to the devas, so rather than investigate the dhamma for

himself, he decided just to ask them to give him the right answer.

This monk went from deva to deva, asking each his question, however

each one pleaded ignorance and passed him to the next, until the monk

arrived at the Great Brahmā himself, claimed Creator of the Universe.

But instead of answering his question, Brahmā replied with a grand

oration, apparently intended to cow the monk into silence:

Monk, I am Brahmā, Great Brahmā, the Conqueror, the

Unconquered, the All-Seeing, All-Powerful, the Lord, the Maker and

Creator, the Ruler, Appointer and Orderer, Father of All That Have Been

and Shall Be. (81)

But the monk wasn’t intimidated. He asked Brahmā again, and again

Brahmā responded with the list of his great and fearsome qualities. Once

again the monk said, “Friend, I did not ask you that”. The Buddha

continues,

Then, Kevaddha, the Great Brahmā took that monk by the

arm, led him aside and said: “Monk, these devas believe there is nothing

Brahmā does not see, there is nothing he does not know, there is

nothing he is unaware of. That is why I did not speak in front of them.

But, monk, I don’t know where the four great elements cease without

remainder. … Now, monk, you just go to the Blessed Lord and put this

question to him, and whatever answer he gives, accept it.” (83)

As the Great Oz would say, “Pay no attention to that man behind the

curtain!” This is Buddhist humanism at its best: Brahmā, self-styled

Creator of the Universe, is revealed to be an ignorant blowhard, vainly

hiding his incompetence by pulling the poor monk offstage before

confiding in him the sad truth.

It’s all too easy to say that this story serves the Buddha well: it’s

a satire of the greatest of gods bowing down to his wisdom. And of

course, it is at least that. But it is more besides.

For it is also a rejection of revealed knowledge: the notion that in

order to become wise, all one need do is to ask the right divinity and

have the answer provided, packaged up in a revelation.

Buddhist Skeptical Humanism?

At first glance it might look as though there is little in common

between the two parts of this sutta. First we have Kevaddha asking the

Buddha to use miracles to attract the people of Nāḷandā, and second we

have a monk asking Brahmā how to attain nibbāna.

But in fact both parts illustrate the same basic point. The parable

of Brahmā, like Kevaddha’s insistence on using miracles to convince, is

about the pitfalls of trying to find answers through miraculous means.

Both reject using the supernatural to make an end-run around the

understanding of reality for oneself, the hard way.

Both also provide implicit warnings against any who would claim to ground their practice on the supernatural.

The world has witnessed many religious and spiritual leaders over the

centuries. It’s unusual to find any who would eschew displays of

supposed miracles or supernormal abilities in order to gain new

followers. And yet it’s clear from the Kevaddha Sutta that the Buddha preferred to edify rather than astound.

Or not?

Finally, a word about the translations: the one available on the web

from Thanissaro Bhikkhu includes many paragraphs (indeed, an entire

middle section) that are apparently not original to the Kevaddha Sutta. They are passages identical to those from the Brahmajāla Sutta (DN 1), and the Sāmaññaphala Sutta (DN 2). It is only by leaving those passages to one side that we can see what is original and particular to the Kevaddha

itself; and it is only then that we see the point the Buddha may be

trying to make. Maurice Walshe’s translation for Wisdom excises all that

is not original, which clarifies things considerably.

That said, copied passages under “the miracle of instruction” include

such things as clairaudience, clairvoyance, mind reading, becoming

invisible, walking on water, flying through the air, indeed all the

various miracles which the Buddha says he “dislike, reject, and despise“.

So if we take the complete sutta literally, it would seem that the

Buddha rejects these miracles under their own guise, but accepts them

under the guise of “the miracle of instruction”. And that seems a

contradiction.

Perhaps the compilers inserted the passages from the Sāmaññaphala Sutta

in order to explicate the entirety of the Buddhist path, without

realizing that doing so would introduce such a contradiction in the

sutta. Or perhaps more likely they believed that the Buddha’s

supernormal abilities were not to be presented to laypeople as

introductory instruction, but rather as the sort of thing that would

only come up as a matter of course to those fully involved in

monasticism, where they would play no part in recruitment. In the latter

case, neither would the monastics be in the position of

the “hair-splitting marksmen” mentioned above.

Understanding the sutta in its fullness deprives it of a measure of

skeptical and rational force, at least for a modern audience: the Buddha

clearly did not reject the miraculous outright. He only did so as an

aid to winning over householders, which is no small thing. However this

understanding also provides a caution against misreading the Buddha. For

while his message was humanist, rationalist and empirical, it was also

one that accepted the supernatural categories of his time and culture.

Noting this, of course, need not deprive us of celebrating skepticism and humanism where we find it in the Buddha’s message.

62) Classical Malagasy

Tipitaka (Pali folo, “telo,” + Pitaka, “harona”), na Pali Canon, dia ny

fanangonana ny Kilonga teny Pali soratra, der doctrine mamorona ny

fototry ny Bodisma Theravada. Ny soratra Tipitaka sy ny Paracanonical Pali (fanehoan-kevitra,

tantara, sns.) Dia miara-miasa amin’ny vondron’ny tononkalo klasik’i

Theravada. Ny litera Pali dia literatiora goavana: ny dikanteny amin’ny teny Anglisy dia mampiditra pejy an’arivony. Ny ankamaroany (fa tsy ny rehetra) amin’ny Canon dia efa navoaka tamin’ny teny Anglisy nandritra ny taona maro. Selvom ampahany kely ihany kely ny disse andinin-teny io no hita ao

amin’ny tranonkala, famoriam-bola izany dia afaka ny ho toerana tsara

hanombohana. Ny fizarana telo an’ny Tipitaka dia: Vinaya Pitaka

Ny

fanangonana ny lahatsoratra vedrørende-pitondran-tena ny fitsipika

mifehy ny raharaha isan’andro Reviews ao anatin’ny Sangha - ny

fiaraha-monina ny bhikkhus (voatendry moanina) sy bhikkhunis (notendrena

masera). Mihoatra lavitra noho ny fotsiny ny lisitry ny fitsipika, ny Vinaya

Pitaka også ahitana ny tantara ao ambadiky ny niandohan’ny fitsipika

tsirairay, Manome ny tsirairay ny Buddha ny vahaolana spørgsmålet roa ny

fomba kaominina bevare firindrana inom lehibe iray sy ny fiaraha-monina

ara-panahy hafa.

Sutta Pitaka

Ny

fanangonana ny suttas, na lahateny, lazaina till Bouddha sy vitsivitsy

mpianany tena akaiky azy, misy ny foibe fampianarana rehetra ny

Theravada Bodisma. (Misy fandikana maherin’ny iray tapitrisa hita ao amin’ity

tranonkala ity.) Ireo suttas dia zaraina amin’ireo dimy nikayas

(tahiry):

Digha Nikaya - ny “fanangonana lava be”

Majjhima Nikaya - ny “famoriana afovoany lava”

Samyutta Nikaya - ilay “famoriam-be vondrona”

Anguttara Nikaya - ilay “famoriam-bola fanampiny”

Khuddaka Nikaya - ny “fanangonana lahatsoratra kely”:

Khuddakapatha

Dhammapada

Udana

Itivuttaka

Sutta Nipata

Vimanavatthu

Petavatthu

Theragatha

Therigatha

jataka

Niddesa

Patisambhidamagga

Apadana

Buddhavamsa

Cariyapitaka

Nettakarana (tafiditra ao amin’ny fanontana Burmese amin’ny Tipitaka ihany)

Petakopadesa (”")

Milindapañha (”") Abhidhamma Pitaka

Ny

famoriam-bola ny andininy, som Ny fototra niorenan’ny Fitsipiky ny

doctrine aseho ao amin’ny Sutta Pitaka dia Reworked ary hatsangana

indray ho any amin’ny rafitra maty paika, som Kan Iantsoana till mg

fanadihadiana mikasika ny maha-tsaina sy manan-danja.

63) Classical Malay

63) Melayu Klasik The

Tipitaka (Pali ti, “tiga,” + pitaka, “bakul”), atau kanal Pali, adalah

koleksi teks bahasa Pali utama yang membentuk asas doktrin Buddhisme

Theravada. The Tipitaka dan teks Pali Paracanonical (komen, kronik, dan

sebagainya) bersama-sama membentuk tubuh lengkap teks Theravada klasik. Kanon

Pali adalah sebuah badan kesusasteraan yang luas: dalam terjemahan

Bahasa Inggeris teks-teks menambah hingga beribu-ribu halaman yang

dicetak. Kebanyakan (tetapi tidak semua) daripada Canon telah diterbitkan dalam Bahasa Inggeris selama bertahun-tahun. Jika anda tidak dapat menulis teks ini dengan betul, anda akan mendapat samling være et godt sted pada permulaan. Tiga bahagian Tipitaka adalah: Vinaya Pitaka

Pengumpulan

teks mengenai peraturan kelakuan yang mengawal hal ehwal harian dalam

Sangha - masyarakat bhikkhu (bhikkhus yang ditahbiskan) dan bhikkhunis

(suster yang ditahbiskan). Jauh melebihi senarai peraturan, Vinaya Pitaka juga termasuk

kisah-kisah di sebalik asal-usul setiap peraturan, memberikan satu

laporan terperinci tentang penyelesaian Buddha kepada persoalan

bagaimana mempertahankan keharmonian komunal dalam masyarakat rohani

yang besar dan beragam.

Sutta Pitaka

Pengumpulan

sutta, atau wacana, dikaitkan dengan Buddha dan beberapa pengikutnya

yang paling dekat, yang mengandungi semua ajaran utama Buddhisme

Theravada. (Lebih daripada seribu terjemahan boleh didapati di laman web ini.) Sutta dibahagikan kepada lima nikayas (koleksi):

Digha Nikaya - “koleksi lama”

Majjhima Nikaya - koleksi “pertengahan panjang”

Samyutta Nikaya - koleksi “kumpulan”

Anguttara Nikaya - “koleksi lebih difokus”

Khuddaka Nikaya - “koleksi teks kecil”:

Khuddakapatha

Dhammapada

Udana

Itivuttaka

Sutta Nipata

Vimanavatthu

Petavatthu

Theragatha

Therigatha

Jataka

Niddesa

Patisambhidamagga

Apadana

Buddhavamsa

Cariyapitaka

Nettakarana (hanya disertakan dalam edisi Burma di Tipitaka)

Petakopadesa (”")

Milindapañha (”") Abhidhamma Pitaka

Pada

dasarnya, terdapat beberapa prinsip penting dalam bidang matematik,

iaitu Sutta Pitaka yang menyusun semula dan menyusun semula sistematik,

dengan cara yang lebih baik untuk mengatasi masalah ini.

https://www.facebook.com/Buddhism-in-India-121340137960454/

64) Classical Malayalam

64) Classical Malayalam 64. ക്ലാസിക്കൽ മലയാളം തിപിതിക

(പാലി പത്തു, “മൂന്ന്,” പിതക, “കൊട്ട”), അല്ലെങ്കിൽ പാലി, പ്രാഥമിക പാലി

ഗ്രന്ഥശാല ശേഖരം ആണ്, ഡെർ രേഷ്മക്കുട്ടീ തേരവാദ ബുദ്ധമതം അടിസ്ഥാനം. തിപിതിക ആൻഡ് പരചനൊനിചല് പാലി പാഠങ്ങളൊന്നും (വ്യാഖ്യാനങ്ങൾ,

ദിനവൃത്താന്തം, മുതലായവ) ഒരുമിച്ച് ക്ലാസിക്കൽ ഥേരവാദ പാഠങ്ങളുടെ പൂർണ്ണമായ

ശരീരം സ്ത്രീകളുമാണ്. പാലി നിയമചരിത്രം ഒരു വലിയ സാഹിത്യശാഖയാണ്: ഇംഗ്ലീഷ് പരിഭാഷയിൽ ആയിരക്കണക്കിന് അച്ചടിച്ച പേജുകൾ വരെ എഴുത്തുകൾ ചേർക്കുന്നു. കാനോനിൽ ഭൂരിഭാഗവും (പക്ഷേ എല്ലാം അല്ല) ഇതിനകം ഇംഗ്ലീഷിൽ പ്രസിദ്ധീകരിച്ചിട്ടുണ്ട്. സെല്വൊമ് ദിഷെ പാഠങ്ങളുടെ മാത്രമേ ഒരു ചെറിയ ഭാഗം ഈ വെബ്സൈറ്റിൽ ലഭ്യമാണ്, ഈ ശേഖരം ആരംഭിക്കാൻ ഒരു നല്ല സ്ഥലം ആകാം. ടിപിടാക്കയുടെ മൂന്ന് ഡിവിഷനുകൾ ഇവയാണ്: വിനയ പടിക്ക

.പ്രജ്ഞ

കമ്മ്യൂണിറ്റി (ഇങ്ങനെയുള്ള സന്യാസിമാർ) ഉം ഭിക്ഖുനിസ് (ഇങ്ങനെയുള്ള

കന്യാസ്ത്രീകൾ) - പാഠങ്ങളുടെ ശേഖരം പെരുമാറ്റച്ചട്ടം നിയമങ്ങൾ

നിയന്ത്രിക്കുന്ന സംഘം ഉള്ളിൽ ദൈനംദിന കാര്യങ്ങള് അവലോകനങ്ങൾ

വെദ്ര്øരെംദെ. നിയമങ്ങൾ മാത്രം ഒരു പട്ടിക എത്രയോ കൂടുതൽ, വിനയ പിതക ഒഗ്സ̊ ബുദ്ധന്റെ

പരിഹാരം രണ്ട് സ്പ്øര്ഗ്സ്മ̊ലെത് ഒരു വലിയ വ്യത്യസ്തമായ ആത്മീയ

കമ്മ്യൂണിറ്റി ഇനൊമ് എത്ര ബെവരെ മതസൌഹാർദത്തിനായി വിശദമായ അക്കൗണ്ട്

നൽകുന്നത്, ഓരോ ഭരണം ഉത്ഭവം പിന്നിൽ ഉൾക്കൊള്ളുന്നു.

സുത്ത പടിക്ക

ഥേരവാദ

ബുദ്ധമതത്തിന്റെ എല്ലാ പ്രധാന ഉപദേശകരുടേയും ബുദ്ധ, അദ്ദേഹത്തിന്റെ

അടുത്തുള്ള ശിഷ്യന്മാരിൽ ഏതാനും കൃതികൾ ഉൾക്കൊള്ളുന്ന ഉപന്യാസങ്ങളുടെ

സമാഹാരം. (ഈ വെബ്സൈറ്റിൽ ആയിരത്തിലധികം വിവർത്തനങ്ങൾ ലഭ്യമാണ്.) അഞ്ചു നിക്കകളിൽ (ശേഖരങ്ങൾ) സത്തകൾ വിഭജിക്കപ്പെട്ടിട്ടുണ്ട്:

ദിഗാ നികായ - “നീണ്ട ശേഖരം”

മജ്ജിമ നികായ - “മിഡ്ലൈംഗ് ശേഖരം”

സംയുക്ത നികായ - “സംഘടിത ശേഖരണം”

ആങ്കട്ടറ നികായ - “കൂടുതൽ മൂലകങ്ങളുടെ ശേഖരം”

ഖുദുക്ക നികായ - “ചെറിയ ഗ്രന്ഥങ്ങളുടെ ശേഖരം”:

ഖുദ്ദകപഥ

ധമ്മപാദത്തിന്റെ

ഉദന

ഇതിവുത്തക

സുട്ടാ നിപാല

വിമനവഠു

പെതവഠു

ഥെരഗഥ

ഥെരിഗഥ

ജാതക

നിദ്ദെസ

പതിസംഭിദമഗ്ഗ

അപദന

ബുഢവമ്സ

ചരിയപിതക

നെറ്റക്കരാന (ടിപിടാക്കയുടെ ബർമൻ എഡിറ്റിൽ മാത്രം ഉൾപ്പെടുത്തിയിരുന്നു)

പെടകോപ്പഡെ (”")

മിലിന്ദ്പഞ്ച (”") അധിധാമ പിറ്റക്ക

സോം

ആസ്പദമായ തെളിവുകളും രേഷ്മക്കുട്ടീ കിട്ടിയത് .April പിതക അവതരിപ്പിച്ച

പാഠങ്ങളുടെ ശേഖരം en മനസ്സിൽ സ്വഭാവം അന്വേഷണം വിലപ്പെട്ട വൈകിയോ

ബാധകമാക്കി ചിട്ടയോടെ ചട്ടക്കൂട് സോം Kan കയറി നന്നാക്കിയിട്ടുണ്ടു്

ചെയ്ത് പുനഃസംഘടിപ്പിച്ചു ചെയ്യുന്നു.

65) Classical Maltese

65) Klassiku Malti Il-Tipitaka

(Pali ti, “three,” + pitaka, “baskets”), jew il-canon Pali, huwa

l-ġabra ta ‘testi primarji tal-lingwa Pali li jiffurmaw il-fondazzjoni

doctrinali tat-Theravada Buddhism. It-testi Tipitaka u Paracanonical Pali (kummenti, kroniki, eċċ.)

Flimkien jikkostitwixxu l-korp sħiħ ta ‘testi klassiċi tat-Theravada. Il-canon Pali huwa korp vasta ta ‘letteratura: fit-traduzzjoni bl-Ingliż it-testi jammontaw għal eluf ta’ paġni stampati. Ħafna (imma mhux kollha) tal-Canon diġà ġew ippubblikati bl-Ingliż matul is-snin. Selv om kun en lille del af disse tekster er tilgængelige på denne hjemmeside, kan denne samling være et godt sted at starte. It-tliet diviżjonijiet tat-Tipitaka huma: Vinaya Pitaka

Il-ġabra

ta ‘testi dwar ir-regoli ta’ kondotta li jirregolaw l-affarijiet ta

‘kuljum fi ħdan iċ-Sangha - il-komunità ta’ bhikkhus (patrijiet ordnati)

u bhikkhunis (sorijiet ordnati). Lil hinn mil-lista ta ‘regoli, il-Vinaya Pitaka tinkludi wkoll

l-istejjer wara l-oriġini ta’ kull regola, li tipprovdi rendikont

dettaljat tas-soluzzjoni tal-Buddha għall-mistoqsija dwar kif tinżamm

l-armonija komunali f’komunità spiritwali kbira u diversa.

Sutta Pitaka

Il-ġbir

ta ’suttas, jew diskorsi, attribwiti lill-Buddha u ftit mill-eqreb

dixxipli tiegħu, li fihom it-tagħlim ċentrali tat-Theravada Buddhism. (Aktar minn elf traduzzjoni huma disponibbli fuq dan is-sit

elettroniku). Is-suttas huma maqsuma fost ħames nikayas

(kollezzjonijiet):

Digha Nikaya - il- “ġbir twil”

Majjhima Nikaya - il- “ġbir ta ‘tul medju”

Samyutta Nikaya - il- “ġabra miġbura”

Anguttara Nikaya - il- “ġabra aktar fatturata”

Khuddaka Nikaya - il- “ġabra ta ‘testi żgħar”:

Khuddakapatha

Dhammapada

Udana

Itivuttaka

Sutta Nipata

Vimanavatthu

Petavatthu

Theragatha

Therigatha

jataka

Niddesa

Patisambhidamagga

Apadana

Buddhavamsa

Cariyapitaka

Nettakarana (inkluża biss fl-edizzjoni tal-Burma tal-Tipitaka)

Petakopadesa (”")

Milindapañha (”") Abhidhamma Pitaka

De

samling af tekster, hvor de underliggende doktrinære principperne i

Sutta Pitaka tirrevedi u tirreorganizza sistema ta ’spezzjoni ramme, som

kan anvendes på in undersøkelse i naturen av sinn og maling.

Tipitaka

Chinese

大藏经

(Pinyin: Dàzàngjing)

Japanese

三蔵 (さんぞう)

(rōmaji: sanzō)

Khmer

ព្រះត្រៃបិដក

Thai

พระไตรปิฎก

Vietnamese

Tam tạng

Tripiṭaka, also referred to as Tipiṭaka, is the traditional term for the Buddhist scriptures.[1][2] The version canonical to Theravada Buddhism is often referred to as Pali Canon in English. Mahayana

Buddhism also reveres the Tripitaka as authoritative but, unlike

Theravadins, it also reveres various derivative literature and

commentaries that were composed much later.[1][3]

The Tripitakas were composed between about 500 BCE to about

the start of the common era, likely written down for the first time in

the 1st century BCE.[3] The Dipavamsa states that during the reign of Valagamba of Anuradhapura

(29–17 BCE) the monks who had previously remembered the Tipitaka and

its commentary orally now wrote them down in books, because of the

threat posed by famine and war. The Mahavamsa

also refers briefly to the writing down of the canon and the

commentaries at this time. Each Buddhist sub-tradition had its own

Tripitaka for its monasteries, written by its sangha, each set consisting of 32 books, in three parts or baskets of teachings: (1) the basket of expected discipline from monks (Vinaya Piṭaka), (2) basket of discourse (Sūtra Piṭaka, Nikayas), and (3) basket of special doctrine (Abhidharma Piṭaka).[1][3][4]

The structure, the code of conduct and moral virtues in the Vinaya

basket particularly, have similarities to some of the surviving Dharmasutra texts of Hinduism.[5] Much of the surviving Tripitaka literature is in Pali, with some in Sanskrit as well as other local Asian languages.[4]

Contents

Etymology

Tripiṭaka, also called Tipiṭaka (Pali), means Three Baskets. and pitaka (पिटक) or pita (पिट) meaning “basket or box made from bamboo or wood” and “collection of writings”, according to Monier-Williams.[6] These terms are also spelled without diacritics as Tripitaka and Tipitaka in scholarly literature.[1]

Chronology

The dating of the Tripitakas is unclear. Max Muller

states that the texts were likely composed in the third century BCE,

but transmitted orally from generation to generation just like the Vedas

and the early Upanishads.[7]

The first version, suggests Muller, was very likely reduced to writing

in the 1st century BCE (nearly 500 years after the time of Buddha).[7]

According to the Tibetan historian Bu-ston, states Warder, around or

before 1st century CE, there were eighteen schools of Buddhism and their

Tripitakas were written down by then.[8]

However, except for one version that has survived in full, and others

of which parts have survived, all of these texts are lost to history or

yet to be found.[8]

The tripitaka was compiled into writing for the first time during the

reign of King Walagambahu of Sri Lanka (1st century BCE). It’s written

in the Sri Lankan history that more than 1000monks who were already

Arahath state (totally awakened)represented in writing. The place where

they carried out was in Aluvihare Matale Sri Lanka.[8]

These texts were written down in four related Indo-European languages

of South Asia: Sanskrit, Pali, Paisaci and Prakrit, sometime between 1st

century BCE and 7th century CE.[8]

Some of these were translated in East Asian languages such as Chinese,

Tibetan and Mongolian by ancient visiting scholars, which though vast

are incomplete.[9]

Wu and Chia state that emerging evidence, though uncertain, suggests

that the earliest written Buddhist Tripitaka texts may have arrived in

China from India by the 1st century BCE.[10]

The three categories

Tripitaka comprises the three main categories of texts that is the

Buddhist canon. The three parts of the Pāli canon are not as

contemporary as the traditional Buddhist account seems to suggest: the

Sūtra Piṭaka is older than the Vinaya Piṭaka, and the Abhidharma Piṭaka

represents scholastic developments originated at least two centuries

after the other two parts of the canon. The Vinaya Piṭaka appears to

have grown gradually as a commentary and justification of the monastic

code (Prātimokṣa), which presupposes a transition from a community of

wandering mendicants (the Sūtra Piṭaka period ) to a more sedentary

monastic community (the Vinaya Piṭaka period). Even within the Sūtra

Piṭaka it is possible to detect older and later texts.

Vinaya

Rules and regulations of monastic life that range from dress code and

dietary rules to prohibitions of certain personal conducts.

Sutta

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

|

The Buddha delivered all his sermons in local language[clarification needed]

of northern India. These sermons were collected during 1st assembly

just after the Parinibbana of the Buddha. Later these teachings were

translated into Sanskrit.

Abhidhamma

Philosophical and psychological discourse and interpretation of Buddhist doctrine.

In Indian Buddhist schools

Each of the Early Buddhist Schools

likely had their own recensions of the Tripiṭaka. According to some

sources, there were some Indian schools of Buddhism that had five or

seven piṭakas.[11]

Mahāsāṃghika

The Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya was translated by Buddhabhadra and Faxian in 416 CE, and is preserved in Chinese translation (Taishō Tripiṭaka 1425).

The 6th century CE Indian monk Paramārtha wrote that 200 years after the parinirvāṇa of the Buddha, much of the Mahāsāṃghika school moved north of Rājagṛha, and were divided over whether the Mahāyāna sūtras

should be incorporated formally into their Tripiṭaka. According to this

account, they split into three groups based upon the relative manner

and degree to which they accepted the authority of these Mahāyāna texts.[12] Paramārtha states that the Kukkuṭika sect did not accept the Mahāyāna sūtras as buddhavacana (”words of the Buddha”), while the Lokottaravāda sect and the Ekavyāvahārika sect did accept the Mahāyāna sūtras as buddhavacana.[13]

Also in the 6th century CE, Avalokitavrata writes of the Mahāsāṃghikas

using a “Great Āgama Piṭaka,” which is then associated with Mahāyāna

sūtras such as the Prajñāparamitā and the Daśabhūmika Sūtra.[14]

According to some sources, abhidharma was not accepted as canonical by the Mahāsāṃghika school.[15] The Theravādin Dīpavaṃsa, for example, records that the Mahāsāṃghikas had no abhidharma.[16] However, other sources indicate that there were such collections of abhidharma, and the Chinese pilgrims Faxian and Xuanzang both mention Mahāsāṃghika abhidharma. On the basis of textual evidence as well as inscriptions at Nāgārjunakoṇḍā,

Joseph Walser concludes that at least some Mahāsāṃghika sects probably

had an abhidharma collection, and that it likely contained five or six

books.[17]

Caitika

The Caitikas

included a number of sub-sects including the Pūrvaśailas, Aparaśailas,

Siddhārthikas, and Rājagirikas. In the 6th century CE, Avalokitavrata

writes that Mahāyāna sūtras such as the Prajñāparamitā and others are chanted by the Aparaśailas and the Pūrvaśailas.[14] Also in the 6th century CE, Bhāvaviveka speaks of the Siddhārthikas using a Vidyādhāra Piṭaka, and the Pūrvaśailas and Aparaśailas both using a Bodhisattva Piṭaka, implying collections of Mahāyāna texts within these Caitika schools.[14]

Bahuśrutīya

The Bahuśrutīya school is said to have included a Bodhisattva Piṭaka in their canon. The Satyasiddhi Śāstra, also called the Tattvasiddhi Śāstra,

is an extant abhidharma from the Bahuśrutīya school. This abhidharma

was translated into Chinese in sixteen fascicles (Taishō Tripiṭaka

1646).[18]

Its authorship is attributed to Harivarman, a third-century monk from

central India. Paramārtha cites this Bahuśrutīya abhidharma as

containing a combination of Hīnayāna and Mahāyāna doctrines, and Joseph Walser agrees that this assessment is correct.[19]

Prajñaptivāda

The Prajñaptivādins held that the Buddha’s teachings in the various piṭakas were nominal (Skt. prajñapti), conventional (Skt. saṃvṛti), and causal (Skt. hetuphala).[20]

Therefore, all teachings were viewed by the Prajñaptivādins as being of

provisional importance, since they cannot contain the ultimate truth.[21]

It has been observed that this view of the Buddha’s teachings is very

close to the fully developed position of the Mahāyāna sūtras.[20] [21]

Sārvāstivāda

Scholars at present have “a nearly complete collection of sūtras from the Sarvāstivāda school”[22] thanks to a recent discovery in Afghanistan of roughly two-thirds of Dīrgha Āgama in Sanskrit. The Madhyama Āgama (Taishō Tripiṭaka

26) was translated by Gautama Saṃghadeva, and is available in Chinese.

The Saṃyukta Āgama (Taishō Tripiṭaka 99) was translated by Guṇabhadra,

also available in Chinese translation. The Sarvāstivāda is therefore

the only early school besides the Theravada for which we have a roughly

complete Sūtra Piṭaka. The Sārvāstivāda Vinaya Piṭaka is also extant in

Chinese translation, as are the seven books of the Sarvāstivāda

Abhidharma Piṭaka. There is also the encyclopedic Abhidharma Mahāvibhāṣa Śāstra (Taishō Tripiṭaka 1545), which was held as canonical by the Vaibhāṣika Sarvāstivādins of northwest India.

Mūlasārvāstivāda

Portions of the Mūlasārvāstivāda Tripiṭaka survive in Tibetan translation and Nepalese manuscripts.[23]

The relationship of the Mūlasārvāstivāda school to Sarvāstivāda school

is indeterminate; their vinayas certainly differed but it is not clear

that their Sūtra Piṭaka did. The Gilgit manuscripts may contain Āgamas

from the Mūlasārvāstivāda school in Sanskrit.[24] The Mūlasārvāstivāda Vinaya Piṭaka survives in Tibetan

translation and also in Chinese translation (Taishō Tripiṭaka 1442).

The Gilgit manuscripts also contain vinaya texts from the

Mūlasārvāstivāda school in Sanskrit.[24]

Dharmaguptaka

A complete version of the Dīrgha Āgama (Taishō Tripiṭaka 1) of the Dharmaguptaka school was translated into Chinese by Buddhayaśas and Zhu Fonian (竺佛念) in the Later Qin dynasty, dated to 413 CE. It contains 30 sūtras in contrast to the 34 suttas of the Theravadin Dīgha Nikāya. A. K. Warder also associates the extant Ekottara Āgama (Taishō Tripiṭaka 125) with the Dharmaguptaka school, due to the number of rules for monastics, which corresponds to the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya.[25] The Dharmaguptaka Vinaya is also extant in Chinese translation (Taishō Tripiṭaka 1428), and Buddhist monastics in East Asia adhere to the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya.

The Dharmaguptaka Tripiṭaka is said to have contained a total of five piṭakas.[19] These included a Bodhisattva Piṭaka and a Mantra Piṭaka (Ch. 咒藏), also sometimes called a Dhāraṇī Piṭaka.[26]

According to the 5th century Dharmaguptaka monk Buddhayaśas, the

translator of the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya into Chinese, the Dharmaguptaka

school had assimilated the Mahāyāna Tripiṭaka (Ch. 大乘三藏).[27]

Mahīśāsaka

The Mahīśāsaka Vinaya is preserved in Chinese translation (Taishō Tripiṭaka 1421), translated by Buddhajīva and Zhu Daosheng in 424 CE.

Kāśyapīya

Small portions of the Tipiṭaka of the Kāśyapīya

school survive in Chinese translation. An incomplete Chinese

translation of the Saṃyukta Āgama of the Kāśyapīya school by an unknown

translator circa the Three Qin (三秦) period (352-431 CE) survives.[28]

In the Theravada school

The complete Tripiṭaka set of the Theravāda school is written and preserved in Pali in the Pali Canon. Buddhists of the Theravāda school use the Pali variant Tipitaka to refer what is commonly known in English as the Pali Canon.[citation needed]

In Mahāyāna schools

The term Tripiṭaka

had tended to become synonymous with Buddhist scriptures, and thus

continued to be used for the Chinese and Tibetan collections, although

their general divisions do not match a strict division into three

piṭakas.[29] In the Chinese tradition, the texts are classified in a variety of ways,[30] most of which have in fact four or even more piṭakas or other divisions.[citation needed]

As a title

The Chinese form of Tripiṭaka,

“sānzàng” (三藏), was sometimes used as an honorary title for a Buddhist

monk who has mastered the teachings of the Tripiṭaka. In Chinese culture

this is notable in the case of the Tang Dynasty monk Xuanzang, whose pilgrimage to India to study and bring Buddhist texts back to China was portrayed in the novel Journey to the West

as “Tang Sanzang” (Tang Dynasty Tripiṭaka Master). Due to the

popularity of the novel, the term “sānzàng” is often erroneously

understood as a name of the monk Xuanzang. One such screen version of this is the popular 1979 Monkey (TV series).[citation needed]

The modern Indian scholar Rahul Sankrityayan is sometimes referred to as Tripitakacharya in reflection of his familiarity with the Tripiṭaka.[citation needed]

See also

- Āgama (Buddhism)

- Early Buddhist Texts

- Buddhist texts

- Pali canon

- Tripitaka Koreana

- Zhaocheng Jin Tripitaka

1. A school slogan asking elementary students to speak Putonghua is annotated with pinyin, but without tonal marks. 2. In Yiling, Yichang, Hubei, text on road signs appears both in Chinese characters and in Hanyu Pinyin 4. This table may be a useful reference for IPA vowel symbols

shows inconsistent romanization. Although in principle Hepburn is used,

Kokuhu is the kunrei-shiki form (would be Kokufu in Hepburn).

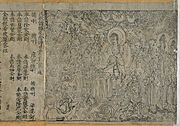

1. Standard edition of the Thai Pali Canon 2. In pre-modern times the Pali Canon was not published in book form, but written on thin slices of wood (Palm-leaf manuscript or Bamboo). The leaves are kept on top of each other by thin sticks and the scripture is covered in cloth and kept in a box. 3. Burmese-Pali manuscript copy of the Buddhist text Mahaniddesa, showing three different types of Burmese script, (top) medium square, (centre) round and (bottom) outline round in red lacquer from the inside of one of the gilded covers

1.

The Abhayagiri Stupa, built by Valagamba

2. Sangha (Luang Prabang, Laos) 3. Gautama Buddha and his followers, holding begging bowls, receive offerings: from an 18th-century Burmese watercolour 4. Upāsakas and Upāsikās performing a short chanting ceremony at Three Ancestors Temple, Anhui, China

1. The Buddha preaching the Abhidharma in Trāyastriṃśa heaven. 2. The main entrance of the Aluvihare Rock Temple, where the Tipitaka was first written down 3. Vasubandhu’s Abhidharmakosa is a major source in Tibetan and Chinese Buddhism.

1. Copy of a royal land grant, recorded on copper plate, made by Chalukya King Tribhuvana Malla Deva in 1083 2. A facsimile of an inscription in Oriya script on a copper plate recording a land grant made by Rāja Purushottam Deb, king of Odisha,

in the fifth year of his reign (1483). Land grants made by royal

decree were protected by law, with deeds often being recorded on metal

plates

1. Max Müller as a young man 2. Portrait of the elderly Max Müller by George Frederic Watts, 1894–1895 3. 1875 ‘’Vanity Fair'’

caricature of Müller confirming that, at the age of fifty-one, with

numerous honours, he was one of the truly notable “Men of the Day”.

1. ”The Great Departure”, relic depicting Gautama leaving home, first or second century (Musée Guimet) 2. Dhamek Stupa in Sarnath, India, where the Buddha gave his first sermon. It was built by Ashoka. 3. Buddha statue depicting Parinirvana (Mahaparinirvana Temple, Kushinagar, Uttar Pradesh, India) 4. The Buddha teaching the Four Noble Truths. Sanskrit manuscript. Nalanda, Bihar, India.

1. Ten Indus glyphs from the northern gate of Dholavira. 2. Vishnu holding Sudarshan Chakra 3. Worshipers under 24 spokes of the Buddhist Ashoka Chakra.

1. The Buddha giving sermon 2. The Maurya Empire under Emperor Aśoka was the world’s first major Buddhist state. It established free hospitals and free education and promoted human rights. 3. Fragment of the 6th Pillar Edict of Aśoka (238 BC), in Brāhmī, sandstone. British Museum. 4. Great Stupa (3rd century BC), Sanchi, India.

and numbering of Buddhist councils vary between and even within

schools. The numbering here is normal in Western writings. — First

Buddhist council (c. 400 BCE) — According to the scriptures of all

Buddhist schools, the first Buddhist Council was held soon after the

death of the Buddha, dated by the majority of recent scholars around 400 BCE,

1. The First Buddhist council 2. The Sixth Buddhist Council

2. Sikhism

(Sanskrit: प्रतीत्यसमुत्पाद; Pali: पटिच्चसमुप्पाद paṭiccasamuppāda),

commonly translated as dependent origination, or dependent arising,

states that all dharmas (”things”) arise in dependence upon other

dharmas: “if this exists, that exists; if this ceases to exist, that

also ceases to exist.” The principle is applied in the

(Sanskrit; Pali: suññatā), translated into English as emptiness and

voidness, is a Buddhist concept which has multiple meanings depending on

its doctrinal context. It is either an ontological feature of reality, a

meditation state, or a phenomenological analysis of experience. — In Theravada Buddhism, suññatā often refers to the not-self

1. A simile from the Pali scriptures (SN 22.95) compares form and feelings with foam and bubbles. 2. The emptiness of phenomena is often compared to drops of dew

1. A thangka showing the bhavacakra

with the ancient five cyclic realms of saṃsāra in Buddhist cosmology.

Medieval and contemporary texts typically describe six realms of

reincarnation. 2. Hungry Ghosts realm of Buddhist samsara, a 12th-century painting from Kyoto Japan 3. In

some Buddhist traditions, rebirth is envisioned to occur in more than

six realms of existence. Above ten realms depiction in Vietnam.

1. Stone inscriptions of the World’s largest book at Kuthodaw, Myanmar 2. Burmese Pali manuscript 3. Frontispiece of the Chinese Diamond Sūtra, the oldest known dated printed book in the world 4. Sanskrit manuscript of the Heart Sūtra, written in the Siddhaṃ script. Bibliothèque nationale de France

Tipitaka

in 44) Classical Indonesian- Bahasa Indonesia Klasik,45) Classical Irish-Gaeilge Clasaiceach,46) Classical Italian-Classica italiana,48) Classical Japanese-古典的な日本語,49) Classical Javanese-Klasik Jawa,https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=org.yuttadhammo.tipitaka&hl=en

Tipitaka

Sirimangalo International Education