2436 Fri 10 Nov 2017 LESSON

Tipitaka

1 History of Buddhism in Scotland

in 23) Classical English, 80) Classical Scots Gaelic - Gàidhlig Albannach Clasaigeach,

or Pali canon, is the collection of primary Pali language texts which

form the doctrinal foundation of Theravada Buddhism. The Tipitaka and

the

paracanonical Pali texts (commentaries, chronicles, etc.) together

constitute the complete body of classical Theravada texts.

The

Pali canon is a vast body of literature: in English translation the

texts add up to thousands of printed pages. Most (but not all) of the

Canon has already been published in English over the years. Although

only a small fraction of these texts are available on this website, this

collection can be a good place to start.

The three divisions of the Tipitaka are:

Vinaya Pitaka

The collection of texts concerning the rules of conduct governing the

daily affairs within the Sangha — the community of bhikkhus (ordained

monks) and bhikkhunis (ordained

nuns). Far more than merely a list of rules, the Vinaya Pitaka also

includes the stories behind the origin of each rule, providing a

detailed account of the Buddha’s solution to the question of how to

maintain communal harmony within a large and diverse spiritual

community.

Sutta Pitaka

The

collection of suttas, or discourses, attributed to the Buddha and a few

of his closest disciples, containing all the central teachings of

Theravada Buddhism. (More than one thousand sutta translations are

available on this website.) The suttas are divided among five nikayas (collections):

Digha Nikaya — the “long collection”

Majjhima Nikaya — the “middle-length collection”

Samyutta Nikaya — the “grouped collection”

Anguttara Nikaya — the “further-factored collection”

Khuddaka Nikaya — the “collection of little texts”:

Khuddakapatha

Dhammapada

Udana

Itivuttaka

Sutta Nipata

Vimanavatthu

Petavatthu

Theragatha

Therigatha

Jataka

Niddesa

Patisambhidamagga

Apadana

Buddhavamsa

Cariyapitaka

Nettippakarana (included only in the Burmese edition of the Tipitaka)

Petakopadesa ( ” ” )

Milindapañha ( ” ” )

Abhidhamma Pitaka

The

collection of texts in which the underlying doctrinal principles

presented in the Sutta Pitaka are reworked and reorganized into a

systematic framework that can be applied to an investigation into the

nature of mind and matter.

https://wikivisually.com/wiki/Buddhism_in_Scotland

The arrival of Buddhism in Scotland is relatively recent. In Scotland

Buddhists represent 0.13% of the population.[1] People were asked both

their current religion and that they were brought up in. 6,830 people

gave Buddhism as their current religion, and 4,704 said they were

brought up in it, with an overlap of 3,146.[2]

Contents

1 History of Buddhism in Scotland

2 Samyé Ling

3 Notable Scottish Buddhists

4 See also

5 External links

6 References

History of Buddhism in Scotland

The earliest Buddhist influence on Scotland came through its imperial

connections with South East Asia, and as a result the early connections

were with the Theravada traditions of Burma, Thailand, and Sri Lanka. To

begin with, 150 years ago, this response was primarily scholarly, and a

tradition of study grew up that eventually resulted in the foundation

of the Pali Text Society, which undertook the huge task of translating

the Pali Canon of Theravada Buddhist texts into English.

The main stupa at Samyé Ling monastery in Scotland

The rate of growth was slow but steady through the century, and the

1950s saw the development of interest in Zen Buddhism. In 1967 Kagyu

Samyé Ling Monastery and Tibetan Centre was founded by Tibetan lamas and

refugees Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche and Akong Rinpoche. It is in

Eskdalemuir, in south west Scotland and is the largest Tibetan Buddhist

centre in Western Europe, and part of the Karma Kagyu tradition.

As well there are other Buddhism-based new religious movements such as

the New Kadampa Tradition, Triratna Buddhist Community and Sōka Gakkai

International. The Triratna community maintains a retreat centre at

Balquhidder in the Trossachs.

Samyé Ling

Kagyu Samyé Ling

Monastery and Tibetan Centre monastery—founded in 1967[3]—includes the

largest Buddhist temple in western Europe. There is an associated

community on Holy Isle which is owned by Samyé Ling who belong to the

Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism. The settlements on the island include

the Centre for World Peace and Health and a retreat centre for nuns.

Samyé Ling has also established centres in more than 20 countries,

including Belgium, Ireland, Poland, South Africa, Spain and

Switzerland.[4]

Notable Scottish Buddhists

Stephen Batchelor

Bodhipaksa

Alex Ferns

Rupert Gethin

Ajahn Candasiri

See also

Holy Isle, Firth of Clyde

Buddhism in the United Kingdom

Buddhism by country

Demographics of Scotland

British Asian

Asian-Scots

New Scots

External links

Edinburgh Drikung Kagyu Sangha

Edinburgh Buddhist Centre (FWBO)

Scotland - List of Buddhist groups in Scotland

Portobello Buddhist Priory (OBC)

Edinburgh Theravadan Buddhists

Scottish Wild Geese Sangha (COI)

Diamond Way Buddhism

References

http://www.scotland.gov.uk/stats/bulletins/00398-02.asp

Scotland’s Census 2001: the Registrar-General’s Report to the Scottish

Parliament, General Register Office for Scotland, 2003, page 31

Kate Rew (2010-01-15). “Scotland’s Buddhist retreat”. The Guardian. Retrieved 2010-01-15.

In the Scottish Lowlands, Europe’s first Buddhist monastery turns 40 Retrieved 24 June 2007.

Gar Trinley Yongkhyab Ling

A Vajrayana Buddhist group in Scotland following the Drikung Kagyu

lineage and the enlightened vision of His Eminence Garchen Triptrul

Rinpoche.

Welcome

final

Gar Trinley Yongkhyab Ling is a Vajrayana Buddhist group in Scotland,

following the Drikung Kagyu lineage and the enlightened vision of His

Eminence Garchen Rinpoche.

Under the spiritual direction of Venerable Dorzin Dhondrup Rinpoche, we are based in Edinburgh and we meet twice a month.

We look forward to meeting you!

Vajrayana Buddhist group in Scotland following the Drikung Kagyu

lineage and the enlightened vision of His Eminence Garchen Triptrul

Rinpoche.

80) Classical Scots Gaelic

80) Gàidhlig Albannach Clasaigeach

Tha

Tipitaka (Pali deich, “trì,” + Pitaka, “basgaidean”), no Pali Canan, ‘S

e cruinneachadh de bhun-Pali cànan theacsaichean, der teagasgail nam

bunait Theravada Buddhism. Tha na teacsaichean Tipitaka agus Paracanonical Pali (beachdan,

litrichean, msaa) còmhla mar bhuidheann iomlan de theacsaichean

clasaigeach Theravada.

Is

e buidheann mòr de litreachas a th’ann an canon Pali: ann an

eadar-theangachadh Beurla tha na teacsaichean a ‘cur suas ri mìltean de

dhuilleagan clò-bhuailte. Tha

a ‘chuid as motha (ach chan eil a h-uile h-uile) den Canon air

fhoillseachadh an-toiseach sa Bheurla thar nam bliadhnaichean. Selv om kun en lille del af disse tekster er tilgængelige på denne hjemmeside, kan denne samling være et godt sted at starte.

Is iad na trì roinnean anns an Tipitaka:

Vinaya Pitaka

Cruinneachadh

de theacsaichean a thaobh riaghailtean giùlain a tha a ‘riaghladh

chùisean làitheil taobh a-staigh na Sangha - coimhearsnachd nam bikkhus

(manaich òrdaichte) agus bhikkhunis (beanntan-dubha òrdaichte). Fada a bharrachd na dìreach liosta de na riaghailtean, a ‘gabhail

a-steach Vinaya Pitaka også na sgeulachdan air cùl an tùs gach

riaghailt, a’ toirt cunntas mionaideach air a ‘Buddha a’ fuasgladh dà

spørgsmålet mar bevare coitcheann co-sheirm inom mòr spioradail agus

eadar-mheasgte a ‘choimhearsnachd.

Sutta Pitaka

An

cruinneachadh de suttas, no deasbadan, a chaidh a thoirt don Buddha

agus beagan de na deiscioblaidhean ab ‘fhaisge aige, anns a bheil prìomh

theagasg Theravada Buddhism. (Tha barrachd air mìle eadar-theangachadh ri fhaighinn air an

làrach-lìn seo.) Tha na h-eadar-theangachadh air an roinn am measg còig

nikayas (cruinneachaidhean):

Digha Nikaya - an “cruinneachadh fada”

Majjhima Nikaya - an “cruinneachadh meadhanach fada”

Samyutta Nikaya - an “cruinneachadh buidhne”

Anguttara Nikaya - an “cruinneachadh nas fhasa”

Khuddaka Nikaya - an “cruinneachadh de theacsaichean beaga”:

Khuddakapatha

Dhammapada

Udana

Itivuttaka

Sutta Nipata

Vimanavatthu

Petavatthu

Theragatha

Therigatha

jataka

Niddesa

Patisambhidamagga

Apadana

Buddhavamsa

Cariyapitaka

Nettakarana (a-mhàin ann an eagran Burmese an Tipitaka)

Petakopadesa (”")

Milindapañha (”")

Abhidhamma Pitaka

Tha

an cruinneachadh de theacsaichean ann an Som prionnsabalan teagasgail a

thoirt seachad ann an Sutta Pitaka tha ath-obrachadh agus

ath-eagrachadh a-steach frèam-obrach eagarach Som Kan Gnìomhaichte til

en rannsachadh nàdar inntinn agus Matter.

2436 Fri 10 Nov 2017 LESSON

Tipitaka

Life Sketch of Savitribai Phule – Timeline

in 81) Classical Serbian-Класични српски

Gautama Buddha (c. 563 BCE/480 BCE – c. 483 BCE/400 BCE), also known as Siddhārtha Gautama , Shakyamuni Buddha ,[4] or simply the Buddha, after the title of Buddha, was an ascetic (śramaṇa) and sage,[4] on whose teachings Buddhism was founded.[5] He is believed to have lived and taught mostly in the eastern part of ancient India sometime between the sixth and fourth centuries BCE.[6] [note 3]

Gautama taught a Middle Way between sensual indulgence and the severe asceticism found in the śramaṇa movement[7] common in his region. He later taught throughout other regions of eastern India such as Magadha and Kosala.[6] [8]

Gautama is the primary figure in Buddhism. He is recognized by Buddhists as an enlightened teacher who attained full Buddhahood, and shared his insights to help sentient beings end rebirth and suffering. Accounts of his life, discourses, and monastic

rules are believed by Buddhists to have been summarized after his death

and memorized by his followers. Various collections of teachings

attributed to him were passed down by oral tradition and first committed to writing about 400 years later.

Scholars

are hesitant to make unqualified claims about the historical facts of

the Buddha’s life. Most accept that he lived, taught and founded a

monastic order during the Mahajanapada era during the reign of Bimbisara (c. 558 – c. 491 BCE, or c. 400 BCE),[9] [10] [11] the ruler of the Magadha empire, and died during the early years of the reign of Ajatasatru, who was the successor of Bimbisara, thus making him a younger contemporary of Mahavira, the Jain tirthankara.[12] [13] Apart from the Vedic Brahmins, the Buddha’s lifetime coincided with the flourishing of influential Śramaṇa schools of thought like Ājīvika, Cārvāka, Jainism, and Ajñana.[14] Brahmajala Sutta records sixty-two such schools of thought. It was also the age of influential thinkers like Mahavira (referred to as ‘Nigantha Nataputta’ in Pali Canon),[15] Pūraṇa Kassapa, Makkhali Gosāla, Ajita Kesakambalī, Pakudha Kaccāyana, and Sañjaya Belaṭṭhaputta, as recorded in Samaññaphala Sutta, whose viewpoints the Buddha most certainly must have been acquainted with.[16] [17] [note 4] Indeed, Sariputta and Moggallāna, two of the foremost disciples of the Buddha, were formerly the foremost disciples of Sañjaya Belaṭṭhaputta, the skeptic;[19]

and the Pali canon frequently depicts Buddha engaging in debate with

the adherents of rival schools of thought. There is also philological

evidence to suggest that the two masters, Alara Kalama and Uddaka Ramaputta, were indeed historical figures and they most probably taught Buddha two different forms of meditative techniques.[20] Thus, Buddha was just one of the many śramaṇa philosophers of that time.[21] In an era where holiness of person was judged by their level of asceticism[22] , Buddha was a reformist within the śramaṇa movement, rather than a reactionary against Vedic Brahminism.[23]

While the general sequence of “birth, maturity, renunciation, search,

awakening and liberation, teaching, death” is widely accepted,[24] there is less consensus on the veracity of many details contained in traditional biographies.[25] [26]

The

times of Gautama’s birth and death are uncertain. Most historians in

the early 20th century dated his lifetime as circa 563 BCE to 483 BCE.[1] [27] More recently his death is dated later, between 411 and 400 BCE, while at a symposium on this question held in 1988,[28] [29] [30] the majority of those who presented definite opinions gave dates within 20 years either side of 400 BCE for the Buddha’s death.[1] [31] [note 3] These alternative chronologies, however, have not yet been accepted by all historians.[36] [37] [note 5]

The evidence of the early texts suggests that Siddhārtha Gautama was born into the Shakya

clan, a community that was on the periphery, both geographically and

culturally, of the eastern Indian subcontinent in the 5th century BCE.[42] It was either a small republic, or an oligarchy, and his father was an elected chieftain, or oligarch.[42] According to the Buddhist tradition, Gautama was born in Lumbini, now in modern-day Nepal, and raised in the Shakya capital of Kapilvastu, which may have been either in what is present day Tilaurakot, Nepal or Piprahwa, India.[note 1] He obtained his enlightenment in Bodh Gaya, gave his first sermon in Sarnath, and died in Kushinagar.

No written records about Gautama were found from his lifetime or some centuries thereafter. One Edict of Asoka, who reigned from circa 269 BCE to 232 BCE, commemorates the Emperor’s pilgrimage to the Buddha’s birthplace in Lumbini. Another one of his edicts mentions the titles of several Dhamma texts, establishing the existence of a written Buddhist tradition at least by the time of the Maurya era. These texts may be the precursor of the Pāli Canon.[59] [60] [note 7] The oldest surviving Buddhist manuscripts are the Gandhāran Buddhist texts, reported to have been found in or around Haḍḍa near Jalalabad in eastern Afghanistan and now preserved in the British Library. They are written in the Gāndhārī language using the Kharosthi script on twenty-seven birch bark manuscripts and date from the first century BCE to the third century CE.[61]

The sources for the life of Siddhārtha Gautama are a variety

of different, and sometimes conflicting, traditional biographies. These

include the Buddhacarita, Lalitavistara Sūtra, Mahāvastu, and the Nidānakathā.[62] Of these, the Buddhacarita[63] [64] [65] is the earliest full biography, an epic poem written by the poet Aśvaghoṣa in the first century CE.[66] The Lalitavistara Sūtra is the next oldest biography, a Mahāyāna/Sarvāstivāda biography dating to the 3rd century CE.[67] The Mahāvastu from the Mahāsāṃghika Lokottaravāda tradition is another major biography, composed incrementally until perhaps the 4th century CE.[67] The Dharmaguptaka biography of the Buddha is the most exhaustive, and is entitled the Abhiniṣkramaṇa Sūtra,[68] and various Chinese translations of this date between the 3rd and 6th century CE. The Nidānakathā is from the Theravada tradition in Sri Lanka and was composed in the 5th century by Buddhaghoṣa.[69]

From canonical sources come the Jataka tales,

the Mahapadana Sutta (DN 14), and the Achariyabhuta Sutta (MN 123),

which include selective accounts that may be older, but are not full

biographies. The Jātakas retell previous lives of Gautama as a bodhisattva, and the first collection of these can be dated among the earliest Buddhist texts.[70]

The Mahāpadāna Sutta and Achariyabhuta Sutta both recount miraculous

events surrounding Gautama’s birth, such as the bodhisattva’s descent

from the Tuṣita Heaven into his mother’s womb.

In the earliest Buddhist texts, the nikāyas and āgamas, the Buddha is not depicted as possessing omniscience (sabbaññu)[71] nor is he depicted as being an eternal transcendent (lokottara) being. According to Bhikkhu Analayo,

ideas of the Buddha’s omniscience (along with an increasing tendency to

deify him and his biography) are found only later, in the Mahayana sutras and later Pali commentaries or texts such as the Mahāvastu.[71]

In the Sandaka Sutta, the Buddha’s disciple Ananda outlines an argument

against the claims of teachers who say they are all knowing [72]

while in the Tevijjavacchagotta Sutta the Buddha himself states that he

has never made a claim to being omniscient, instead he claimed to have

the “higher knowledges” (abhijñā).[73] The earliest biographical material from the Pali Nikayas focuses on the Buddha’s life as a śramaṇa, his search for enlightenment under various teachers such as Alara Kalama and his forty-five-year career as a teacher.[74]

Traditional

biographies of Gautama generally include numerous miracles, omens, and

supernatural events. The character of the Buddha in these traditional

biographies is often that of a fully transcendent (Skt. lokottara) and

perfected being who is unencumbered by the mundane world. In the

Mahāvastu, over the course of many lives, Gautama is said to have

developed supramundane abilities including: a painless birth conceived

without intercourse; no need for sleep, food, medicine, or bathing,

although engaging in such “in conformity with the world”; omniscience,

and the ability to “suppress karma”.[75]

Nevertheless, some of the more ordinary details of his life have been

gathered from these traditional sources. In modern times there has been

an attempt to form a secular understanding of Siddhārtha Gautama’s life by omitting the traditional supernatural elements of his early biographies.

Andrew Skilton writes that the Buddha was never historically regarded by Buddhist traditions as being merely human:

It

is important to stress that, despite modern Theravada teachings to the

contrary (often a sop to skeptical Western pupils), he was never seen as

being merely human. For instance, he is often described as having the

thirty-two major and eighty minor marks or signs of a mahāpuruṣa,

“superman”; the Buddha himself denied that he was either a man or a god; and in the Mahāparinibbāna Sutta he states that he could live for an aeon were he asked to do so.[76]

The

ancient Indians were generally unconcerned with chronologies, being

more focused on philosophy. Buddhist texts reflect this tendency,

providing a clearer picture of what Gautama may have taught than of the

dates of the events in his life. These texts contain descriptions of the

culture and daily life of ancient India which can be corroborated from

the Jain scriptures, and make the Buddha’s time the earliest period in Indian history for which significant accounts exist.[77] British author Karen Armstrong

writes that although there is very little information that can be

considered historically sound, we can be reasonably confident that

Siddhārtha Gautama did exist as a historical figure.[78]

Michael Carrithers goes a bit further by stating that the most general

outline of “birth, maturity, renunciation, search, awakening and

liberation, teaching, death” must be true.[24]

The Buddhist tradition regards Lumbini, in present-day Nepal to be the birthplace of the Buddha.[80] [note 1] He grew up in Kapilavastu.[note 1] The exact site of ancient Kapilavastu is unknown.[81] It may have been either Piprahwa, Uttar Pradesh, in present-day India,[54] or Tilaurakot, in present-day Nepal.[82] Both places belonged to the Sakya territory, and are located only 15 miles apart.[82]

Gautama was born as a Kshatriya,[83] [note 9] the son of Śuddhodana, “an elected chief of the Shakya clan“,[6] whose capital was Kapilavastu, and who were later annexed by the growing Kingdom of Kosala during the Buddha’s lifetime. Gautama was the family name. His mother, Maya (Māyādevī), Suddhodana’s wife, was a Koliyan princess. Legend has it that, on the night Siddhartha was conceived, Queen Maya dreamt that a white elephant with six white tusks entered her right side,[85] [86] and ten months later[87]

Siddhartha was born. As was the Shakya tradition, when his mother Queen

Maya became pregnant, she left Kapilavastu for her father’s kingdom to

give birth. However, her son is said to have been born on the way, at

Lumbini, in a garden beneath a sal tree.

The day of the Buddha’s birth is widely celebrated in Theravada countries as Vesak.[88] Buddha’s Birthday is called Buddha Purnima

in Nepal, Bangladesh, and India as he is believed to have been born on a

full moon day. Various sources hold that the Buddha’s mother died at

his birth, a few days or seven days later. The infant was given the name

Siddhartha (Pāli: Siddhattha), meaning “he who achieves his aim”.

During the birth celebrations, the hermit seer Asita journeyed from his mountain abode and announced that the child would either become a great king (chakravartin) or a great sadhu.[89]

By traditional account, this occurred after Siddhartha placed his feet

in Asita’s hair and Asita examined the birthmarks. Suddhodana held a

naming ceremony on the fifth day, and invited eight Brahmin scholars to read the future. All gave a dual prediction that the baby would either become a great king or a great holy man.[89] Kondañña, the youngest, and later to be the first arhat other than the Buddha, was reputed to be the only one who unequivocally predicted that Siddhartha would become a Buddha.[90]

While later tradition and legend characterized Śuddhodana as a hereditary monarch, the descendant of the Suryavansha (Solar dynasty) of Ikṣvāku (Pāli: Okkāka), many scholars think that Śuddhodana was the elected chief of a tribal confederacy.

Early

texts suggest that Gautama was not familiar with the dominant religious

teachings of his time until he left on his religious quest, which is

said to have been motivated by existential concern for the human

condition.[91] The state of the Shakya clan was not a monarchy and seems to have been structured either as an oligarchy, or as a form of republic.[92]

The more egalitarian gana-sangha form of government, as a political

alternative to the strongly hierarchical kingdoms, may have influenced

the development of the śramanic Jain and Buddhist sanghas, where monarchies tended toward Vedic Brahmanism.[93]

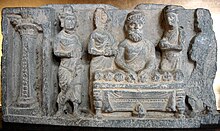

| Birth and childhood of the Buddha |

|

Siddhartha was brought up by his mother’s younger sister, Maha Pajapati.[94]

By tradition, he is said to have been destined by birth to the life of a

prince and had three palaces (for seasonal occupation) built for him.

His father, said to be King Śuddhodana, wishing for his son to be a

great king, is said to have shielded him from religious teachings and

from knowledge of human suffering.

While Śuddhodana has traditionally been depicted as a king, and

Siddhartha as his prince, more recent scholarship suggests the Shakya were in-fact organized as a semi-republican oligarchy rather than a monarchy. [95]

When he reached the age of 16, his father reputedly arranged his marriage to a cousin of the same age named Yaśodharā (Pāli: Yasodharā). According to the traditional account, she gave birth to a son, named Rāhula. Siddhartha is said to have spent 29 years as a prince in Kapilavastu.

Although his father ensured that Siddhartha was provided with

everything he could want or need, Buddhist scriptures say that the

future Buddha felt that material wealth was not life’s ultimate goal.[94]

At

the age of 29, Siddhartha left his palace to meet his subjects. Despite

his father’s efforts to hide from him the sick, aged and suffering,

Siddhartha was said to have seen an old man. When his charioteer Channa explained to him that all people grew old, the prince went on further trips beyond the palace. On these he encountered a diseased man, a decaying corpse, and an ascetic. These depressed him, and he initially strove to overcome ageing, sickness, and death by living the life of an ascetic.[96]

Accompanied by Channa and riding his horse Kanthaka, Gautama quit his palace for the life of a mendicant. It’s said that “the horse’s hooves were muffled by the gods”[97] to prevent guards from knowing of his departure.

Gautama initially went to Rajagaha

and began his ascetic life by begging for alms in the street. After

King Bimbisara’s men recognised Siddhartha and the king learned of his

quest, Bimbisara offered Siddhartha the throne. Siddhartha rejected the

offer but promised to visit his kingdom of Magadha first, upon attaining enlightenment.

He left Rajagaha and practised under two hermit teachers of yogic meditation.[98] [99] [100] After mastering the teachings of Alara Kalama

(Skr. Ārāḍa Kālāma), he was asked by Kalama to succeed him. However,

Gautama felt unsatisfied by the practice, and moved on to become a

student of yoga with Udaka Ramaputta (Skr. Udraka Rāmaputra).[101]

With him he achieved high levels of meditative consciousness and was

again asked to succeed his teacher. But, once more, he was not

satisfied, and again moved on.[102]

According to the early Buddhist texts,[103] after realizing that meditative dhyana was the right path to awakening, but that extreme asceticism didn’t work, Gautama discovered what Buddhists know as being, the Middle Way[103] —a path of moderation away from the extremes of self-indulgence and self-mortification, or the Noble Eightfold Path, as described in the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, which is regarded as the first discourse of the Buddha.[103] In a famous incident, after becoming starved and weakened, he is said to have accepted milk and rice pudding from a village girl named Sujata.[104] Such was his emaciated appearance that she wrongly believed him to be a spirit that had granted her a wish.[104]

Following this incident, Gautama was famously seated under a pipal tree—now known as the Bodhi tree—in Bodh Gaya, India, when he vowed never to arise until he had found the truth.[105] Kaundinya

and four other companions, believing that he had abandoned his search

and become undisciplined, ceased to stay with him, and went to somewhere

else. After a reputed 49 days of meditation, at the age of 35, he is

said to have attained Enlightenment,[105] [106] and became known as the Buddha or “Awakened One” (”Buddha” is also sometimes translated as “The Enlightened One”).

According to some sutras of the Pali canon, at the time of his awakening he realized complete insight into the Four Noble Truths, thereby attaining liberation from samsara, the endless cycle of rebirth, suffering and dying again.[107] [108] [109]

According to scholars, this story of the awakening and the stress on

“liberating insight” is a later development in the Buddhist tradition,

where the Buddha may have regarded the practice of dhyana as leading to Nirvana and moksha.[110] [111] [107] [note 10]

Nirvana

is the extinguishing of the “fires” of desire, hatred, and ignorance,

that keep the cycle of suffering and rebirth going.[112]

Nirvana is also regarded as the “end of the world”, in that no personal

identity or boundaries of the mind remain. In such a state, a being is

said to possess the Ten Characteristics, belonging to every Buddha.

According to a story in the Āyācana Sutta (Samyutta Nikaya VI.1) — a scripture found in the Pāli and other canons — immediately after his awakening, the Buddha debated whether or not he should teach the Dharma

to others. He was concerned that humans were so overpowered by

ignorance, greed and hatred that they could never recognise the path,

which is subtle, deep and hard to grasp. However, in the story, Brahmā Sahampati convinced him, arguing that at least some will understand it. The Buddha relented, and agreed to teach.

After his awakening, the Buddha met Taphussa and Bhallika — two merchant brothers from the city of Balkh

in what is currently Afghanistan — who became his first lay disciples.

It is said that each was given hairs from his head, which are now

claimed to be enshrined as relics in the Shwe Dagon Temple in Rangoon, Burma. The Buddha intended to visit Asita, and his former teachers, Alara Kalama and Udaka Ramaputta, to explain his findings, but they had already died.

He then travelled to the Deer Park near Varanasi (Benares) in northern India, where he set in motion what Buddhists call the Wheel of Dharma

by delivering his first sermon to the five companions with whom he had

sought enlightenment. Together with him, they formed the first saṅgha: the company of Buddhist monks.

All five become arahants, and within the first two months, with the conversion of Yasa

and fifty-four of his friends, the number of such arahants is said to

have grown to 60. The conversion of three brothers named Kassapa

followed, with their reputed 200, 300 and 500 disciples, respectively.

This swelled the sangha to more than 1,000.

For the remaining 45 years of his life, the Buddha is said to have traveled in the Gangetic Plain, in what is now Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and southern Nepal, teaching a diverse range of people: from nobles to servants, murderers such as Angulimala, and cannibals such as Alavaka.[114]

Although the Buddha’s language remains unknown, it’s likely that he

taught in one or more of a variety of closely related Middle Indo-Aryan

dialects, of which Pali may be a standardization.

The

sangha traveled through the subcontinent, expounding the dharma. This

continued throughout the year, except during the four months of the Vassa

rainy season when ascetics of all religions rarely traveled. One reason

was that it was more difficult to do so without causing harm to animal

life. At this time of year, the sangha would retreat to monasteries,

public parks or forests, where people would come to them.

The first vassana was spent at Varanasi when the sangha was formed. After this, the Buddha kept a promise to travel to Rajagaha, capital of Magadha, to visit King Bimbisara. During this visit, Sariputta and Maudgalyayana were converted by Assaji,

one of the first five disciples, after which they were to become the

Buddha’s two foremost followers. The Buddha spent the next three seasons

at Veluvana Bamboo Grove monastery in Rajagaha, the capital of Magadha.

Upon

hearing of his son’s awakening, Suddhodana sent, over a period, ten

delegations to ask him to return to Kapilavastu. On the first nine

occasions, the delegates failed to deliver the message and instead

joined the sangha to become arahants. The tenth delegation, led by

Kaludayi, a childhood friend of Gautama’s (who also became an arahant),

however, delivered the message.

Now two years after his

awakening, the Buddha agreed to return, and made a two-month journey by

foot to Kapilavastu, teaching the dharma as he went. At his return, the

royal palace prepared a midday meal, but the sangha was making an alms

round in Kapilavastu. Hearing this, Suddhodana approached his son, the

Buddha, saying:

“Ours is the warrior lineage of Mahamassata, and not a single warrior has gone seeking alms.”

The Buddha is said to have replied:

“That

is not the custom of your royal lineage. But it is the custom of my

Buddha lineage. Several thousands of Buddhas have gone by seeking alms.”

Buddhist

texts say that Suddhodana invited the sangha into the palace for the

meal, followed by a dharma talk. After this he is said to have become a sotapanna. During the visit, many members of the royal family joined the sangha. The Buddha’s cousins Ananda and Anuruddha became two of his five chief disciples. At the age of seven, his son Rahula also joined, and became one of his ten chief disciples. His half-brother Nanda also joined and became an arahant.

Of the Buddha’s disciples, Sariputta, Maudgalyayana, Mahakasyapa,

Ananda and Anuruddha are believed to have been the five closest to him.

His ten foremost disciples were reputedly completed by the quintet of Upali, Subhoti, Rahula, Mahakaccana and Punna.

In the fifth vassana, the Buddha was staying at Mahavana near Vesali

when he heard news of the impending death of his father. He is said to

have gone to Suddhodana and taught the dharma, after which his father

became an arahant.

The

king’s death and cremation was to inspire the creation of an order of

nuns. Buddhist texts record that the Buddha was reluctant to ordain

women. His foster mother Maha Pajapati,

for example, approached him, asking to join the sangha, but he refused.

Maha Pajapati, however, was so intent on the path of awakening that she

led a group of royal Sakyan and Koliyan ladies, which followed the

sangha on a long journey to Rajagaha. In time, after Ananda championed

their cause, the Buddha is said to have reconsidered and, five years

after the formation of the sangha, agreed to the ordination of women as

nuns. He reasoned that males and females had an equal capacity for

awakening. But he gave women additional rules (Vinaya) to follow.

According to the Mahaparinibbana Sutta of the Pali canon, at the age of 80, the Buddha announced that he would soon reach Parinirvana,

or the final deathless state, and abandon his earthly body. After this,

the Buddha ate his last meal, which he had received as an offering from

a blacksmith named Cunda. Falling violently ill, Buddha instructed his attendant Ānanda

to convince Cunda that the meal eaten at his place had nothing to do

with his passing and that his meal would be a source of the greatest

merit as it provided the last meal for a Buddha.[115] Mettanando and von Hinüber argue that the Buddha died of mesenteric infarction, a symptom of old age, rather than food poisoning.[116] [117]

The

precise contents of the Buddha’s final meal are not clear, due to

variant scriptural traditions and ambiguity over the translation of

certain significant terms; the Theravada tradition generally believes that the Buddha was offered some kind of pork, while the Mahayana

tradition believes that the Buddha consumed some sort of truffle or

other mushroom. These may reflect the different traditional views on Buddhist vegetarianism and the precepts for monks and nuns.

Waley

suggests that Theravadins would take suukaramaddava (the contents of

the Buddha’s last meal), which can translate literally as pig-soft, to

mean “soft flesh of a pig” or “pig’s soft-food”, that is, after Neumann, a soft food favoured by pigs, assumed to be a truffle.

He argues (also after Neumann) that as “(p)lant names tend to be local

and dialectical”, as there are several plants known to have suukara-

(pig) as part of their names,[note 11]

and as Pali Buddhism developed in an area remote from the Buddha’s

death, suukaramaddava could easily have been a type of plant whose local

name was unknown to those in Pali regions. Specifically, local writers

writing soon after the Buddha’s death knew more about their flora than

Theravadin commentator Buddhaghosa

who lived hundreds of years and hundreds of kilometres remote in time

and space from the events described. Unaware that it may have been a

local plant name and with no Theravadin prohibition against eating

animal flesh, Theravadins would not have questioned the Buddha eating

meat and interpreted the term accordingly.[118]

According to Buddhist tradition, the Buddha died at Kuśināra (present-day Kushinagar, India), which became a pilgrimage center.[119] Ananda protested the Buddha’s decision to enter Parinirvana in the abandoned jungles of Kuśināra of the Malla

kingdom. The Buddha, however, is said to have reminded Ananda how

Kushinara was a land once ruled by a righteous wheel-turning king and

the appropriate place for him to die.[120]

The Buddha then asked all the attendant Bhikkhus

to clarify any doubts or questions they had and cleared them all in a

way which others could not do. They had none. According to Buddhist

scriptures, he then finally entered Parinirvana. The Buddha’s final

words are reported to have been: “All composite things (Saṅkhāra)

are perishable. Strive for your own liberation with diligence” (Pali:

‘vayadhammā saṅkhārā appamādena sampādethā’). His body was cremated and

the relics were placed in monuments or stupas, some of which are believed to have survived until the present. For example, the Temple of the Tooth or “Dalada Maligawa” in Sri Lanka is the place where what some believe to be the relic of the right tooth of Buddha is kept at present.

According to the Pāli historical chronicles of Sri Lanka, the Dīpavaṃsa and Mahāvaṃsa, the coronation of Emperor Aśoka (Pāli: Asoka) is 218 years after the death of the Buddha. According to two textual records in Chinese (十八部論 and 部執異論),

the coronation of Emperor Aśoka is 116 years after the death of the

Buddha. Therefore, the time of Buddha’s passing is either 486 BCE

according to Theravāda record or 383 BCE according to Mahayana record.

However, the actual date traditionally accepted as the date of the

Buddha’s death in Theravāda countries is 544 or 545 BCE, because the

reign of Emperor Aśoka was traditionally reckoned to be about 60 years

earlier than current estimates. In Burmese Buddhist tradition, the date

of the Buddha’s death is 13 May 544 BCE.[121] whereas in Thai tradition it is 11 March 545 BCE.[122]

At his death, the Buddha is famously believed to have told his disciples to follow no leader. Mahakasyapa was chosen by the sangha to be the chairman of the First Buddhist Council, with the two chief disciples Maudgalyayana and Sariputta having died before the Buddha.

While

in the Buddha’s days he was addressed by the very respected titles

Buddha, Shākyamuni, Shākyasimha, Bhante and Bho, he was known after his

parinirvana nirvana as Arihant, Bhagavā/Bhagavat/Bhagwān, Mahāvira,[123] Jina/Jinendra, Sāstr, Sugata, and most popularly in scriptures as Tathāgata.

After his death, Buddha’s cremation relics were divided

amongst 8 royal families and his disciples; centuries later they would

be enshrined by King Ashoka into 84,000 stupas.[124] [125]

Many supernatural legends surround the history of alleged relics as

they accompanied the spread of Buddhism and gave legitimacy to rulers.

An extensive and colorful physical description of the Buddha has been laid down in scriptures. A kshatriya

by birth, he had military training in his upbringing, and by Shakyan

tradition was required to pass tests to demonstrate his worthiness as a

warrior in order to marry. He had a strong enough body to be noticed by

one of the kings and was asked to join his army as a general. He is also

believed by Buddhists to have “the 32 Signs of the Great Man”.

The

Brahmin Sonadanda described him as “handsome, good-looking, and

pleasing to the eye, with a most beautiful complexion. He has a godlike

form and countenance, he is by no means unattractive.” (D, I:115)

“It

is wonderful, truly marvellous, how serene is the good Gotama’s

appearance, how clear and radiant his complexion, just as the golden

jujube in autumn is clear and radiant, just as a palm-tree fruit just

loosened from the stalk is clear and radiant, just as an adornment of

red gold wrought in a crucible by a skilled goldsmith, deftly beaten and

laid on a yellow-cloth shines, blazes and glitters, even so, the good

Gotama’s senses are calmed, his complexion is clear and radiant.” (A,

I:181)

A disciple named Vakkali, who later became an arahant, was

so obsessed by the Buddha’s physical presence that the Buddha is said

to have felt impelled to tell him to desist, and to have reminded him

that he should know the Buddha through the Dhamma and not through

physical appearances.

Although there are no extant representations of the Buddha in human form until around the 1st century CE (see Buddhist art), descriptions of the physical characteristics of fully enlightened buddhas are attributed to the Buddha in the Digha Nikaya’s Lakkhaṇa Sutta (D, I:142).[127] In addition, the Buddha’s physical appearance is described by Yasodhara to their son Rahula

upon the Buddha’s first post-Enlightenment return to his former

princely palace in the non-canonical Pali devotional hymn, Narasīha

Gāthā (”The Lion of Men”).[128]

Among the 32 main characteristics it is mentioned that Buddha has blue eyes.[129]

Recollection of nine virtues attributed to the Buddha is a common Buddhist meditation and devotional practice called Buddhānusmṛti. The nine virtues are also among the 40 Buddhist meditation subjects. The nine virtues of the Buddha appear throughout the Tipitaka,[130] and include:

- Sammasambuddho – Perfectly self-awakened

- Vijja-carana-sampano – Endowed with higher knowledge and ideal conduct.

- Sugato – Well-gone or Well-spoken.

- Lokavidu – Wise in the knowledge of the many worlds.

- Anuttaro Purisa-damma-sarathi – Unexcelled trainer of untrained people.

- Satthadeva-Manussanam – Teacher of gods and humans.

- Bhagavathi – The Blessed one

- Araham – Worthy of homage. An Arahant

is “one with taints destroyed, who has lived the holy life, done what

had to be done, laid down the burden, reached the true goal, destroyed

the fetters of being, and is completely liberated through final

knowledge.”

In the Pali Canon, the Buddha uses many Brahmanical devices. For example, in Samyutta Nikaya 111, Majjhima Nikaya 92 and Vinaya i 246 of the Pali Canon, the Buddha praises the Agnihotra as the foremost sacrifice and the Gayatri mantra as the foremost meter:

aggihuttamukhā yaññā sāvittī chandaso mukham.

Sacrifices have the Agnihotra as foremost; of meter, the foremost is the Sāvitrī.[131]

Information of the oldest teachings may be obtained by

analysis of the oldest texts. One method to obtain information on the

oldest core of Buddhism is to compare the oldest extant versions of the

Theravadin Pali Canon and other texts.[note 12] The reliability of these sources, and the possibility of drawing out a core of oldest teachings, is a matter of dispute.[134] [135] [136] [137] According to Vetter, inconsistencies remain, and other methods must be applied to resolve those inconsistencies.[132] [note 13]

According to Schmithausen, three positions held by scholars of Buddhism can be distinguished:[140]

- “Stress on the fundamental homogeneity and substantial authenticity of at least a considerable part of the Nikayic materials;”[note 14] [note 15] , from the oldest extant texts a common kernel can be drawn out.[141]

According to Warder, c.q. his publisher: “This kernel of doctrine is

presumably common Buddhism of the period before the great schisms of the

fourth and third centuries BC. It may be substantially the Buddhism of

the Buddha himself, although this cannot be proved: at any rate it is a

Buddhism presupposed by the schools as existing about a hundred years

after the parinirvana of the Buddha, and there is no evidence to suggest

that it was formulated by anyone else than the Buddha and his immediate

followers”.[141] and Richard Gombrich. [142]

Richard Gombrich: “I have the greatest difficulty in accepting that the

main edifice is not the work of a single genius. By “the main edifice” I

mean the collections of the main body of sermons, the four Nikāyas, and

of the main body of monastic rules.”[137] - “Scepticism with regard to the possibility of retrieving the doctrine of earliest Buddhism;”[note 16] [note 17]

- “Cautious optimism in this respect.”[note 18]

A core problem in the study of early Buddhism is the relation between dhyana and insight.[135] [134] [137]

Schmithausen notes that the mention of the four noble truths as

constituting “liberating insight”, which is attained after mastering the

Rupa Jhanas, is a later addition to texts such as Majjhima Nikaya 36.[138] [134] [135]

According to Tilmann Vetter, the core of earliest Buddhism is the practice of dhyāna,[146] as a workable alternative to painful ascetic practices.[147] [note 19] Bronkhorst agrees that Dhyāna was a Buddhist invention,[134] whereas Norman notes that “the Buddha’s way to release […] was by means of meditative practices.”[149] Discriminating insight into transiency as a separate path to liberation was a later development.[150] [151]

According to the Mahāsaccakasutta,[note 20] from the fourth jhana the Buddha gained bodhi. Yet, it is not clear what he was awakened to.[149] [134]

According to Schmithausen and Bronkhorst, “liberating insight” is a

later addition to this text, and reflects a later development and

understanding in early Buddhism.[138] [134]

The mentioning of the four truths as constituting “liberating insight”

introduces a logical problem, since the four truths depict a linear path

of practice, the knowledge of which is in itself not depicted as being

liberating:[152]

[T]hey

do not teach that one is released by knowing the four noble truths, but

by practicing the fourth noble truth, the eightfold path, which

culminates in right samadhi.[152]

Although “Nibbāna”

(Sanskrit: Nirvāna) is the common term for the desired goal of this

practice, many other terms can be found throughout the Nikayas, which

are not specified.[153] [note 21]

According to Vetter, the description of the Buddhist path may initially have been as simple as the term “the middle way”.[154] In time, this short description was elaborated, resulting in the description of the eightfold path.[154]

According to both Bronkhorst and Anderson, the four truths became a substitution for prajna, or “liberating insight”, in the suttas[111] [107] in those texts where “liberating insight” was preceded by the four jhanas.[155]

According to Bronkhorst, the four truths may not have been formulated

in earliest Buddhism, and did not serve in earliest Buddhism as a

description of “liberating insight”.[156] Gotama’s teachings may have been personal, “adjusted to the need of each person.”[155]

The three marks of existence[note 22]

may reflect Upanishadic or other influences. K.R. Norman supposes that

these terms were already in use at the Buddha’s time, and were familiar

to his listeners.[157]

The Brahma-vihara was in origin probably a brahmanic term;[158] but its usage may have been common to the Sramana traditions.[134]

In time, “liberating insight” became an essential feature of

the Buddhist tradition. The following teachings, which are commonly seen

as essential to Buddhism, are later formulations which form part of the

explanatory framework of this “liberating insight”:[135] [134]

- The Four Noble Truths:

that suffering is an ingrained part of existence; that the origin of

suffering is craving for sensuality, acquisition of identity, and fear

of annihilation; that suffering can be ended; and that following the Noble Eightfold Path is the means to accomplish this; - The

Noble Eightfold Path: right view, right intention, right speech, right

action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right

concentration; - Dependent origination: the mind creates suffering as a natural product of a complex process.

Some Hindus regard Gautama as the 9th avatar of Vishnu.[note 8] [159] However, Buddha’s teachings deny the authority of the Vedas and the concepts of Brahman-Atman.[160] [161] [162] Consequently Buddhism is generally classified as a nāstika school (heterodox, literally “It is not so”[note 23] ) in contrast to the six orthodox schools of Hinduism.[165] [166] [167]

The Buddha is regarded as a prophet by the minority Ahmadiyya[168] sect of Muslims – a sect considered a deviant and rejected as apostate by mainstream Islam.[169] [170] Some early Chinese Taoist-Buddhists thought the Buddha to be a reincarnation of Laozi.[171]

Disciples of the Cao Đài religion worship the Buddha as a major religious teacher.[172]

His image can be found in both their Holy See and on the home altar. He

is revealed during communication with Divine Beings as son of their

Supreme Being (God the Father) together with other major religious

teachers and founders like Jesus, Laozi, and Confucius.[173]

The Christian Saint Josaphat is based on the Buddha. The name comes from the Sanskrit Bodhisattva via Arabic Būdhasaf and Georgian Iodasaph.[174] The only story in which St. Josaphat appears, Barlaam and Josaphat, is based on the life of the Buddha.[175]

Josaphat was included in earlier editions of the Roman Martyrology

(feast day 27 November) — though not in the Roman Missal — and in the

Eastern Orthodox Church liturgical calendar (26 August).

In the ancient Gnostic sect of Manichaeism, the Buddha is listed among the prophets who preached the word of God before Mani.[176]

- Films

- Little Buddha, a 1994 film by Bernardo Bertolucci

- Prem Sanyas, a 1925 silent film, directed by Franz Osten and Himansu Rai

- Television

- Buddha, a 2013 mythological drama on Zee TV

- Literature

- The Light of Asia, an 1879 epic poem by Edwin Arnold

- Buddha, a manga series that ran from 1972 to 1983 by Osamu Tezuka

- Siddhartha novel by Hermann Hesse, written in German in 1922

- Lord of Light, a novel by Roger Zelazny depicts a man in a far future Earth Colony who takes on the name and teachings of the Budda

- Music

- Karuna Nadee, a 2010 oratorio by Dinesh Subasinghe

- The Light of Asia, an 1886 oratorio by Dudley Buck

- According to the Buddhist tradition, following the Nidanakatha,[43] the introductory to the Jataka tales, the stories of the former lives of the Buddha, Gautama was born in Lumbini, present-day Nepal.[44] [45] In the mid-3rd century BCE the Emperor Ashoka

determined that Lumbini was Gautama’s birthplace and thus installed a

pillar there with the inscription: “…this is where the Buddha, sage of

the Śākyas (Śākyamuni), was born.”[46] Based on stone inscriptions, there is also speculation that Lumbei, Kapileswar village, Odisha, at the east coast of India, was the site of ancient Lumbini.[47] [48] [49] Hartmann discusses the hypothesis and states, “The inscription has generally been considered spurious (…)”[50]

He quotes Sircar: “There can hardly be any doubt that the people

responsible for the Kapilesvara inscription copied it from the said

facsimile not much earlier than 1928.” Kapilavastu was the place where

he grew up:[51] [note 6]

- Warder:

“The Buddha […] was born in the Sakya Republic, which was the city

state of Kapilavastu, a very small state just inside the modern state

boundary of Nepal against the Northern Indian frontier.[6] - Walsh:

“He belonged to the Sakya clan dwelling on the edge of the Himalayas,

his actual birthplace being a few miles north of the present-day

Northern Indian border, in Nepal. His father was, in fact, an elected

chief of the clan rather than the king he was later made out to be,

though his title was raja – a term which only partly corresponds to our

word ‘king’. Some of the states of North India at that time were

kingdoms and others republics, and the Sakyan republic was subject to

the powerful king of neighbouring Kosala, which lay to the south”.[53] - The exact location of ancient Kapilavastu is unknown.[51] It may have been either Piprahwa in Uttar Pradesh, northern India,[54] [55] [56] or Tilaurakot,[57] present-day Nepal.[58] [51] The two cities are located only fifteen miles from each other.[58]

- Warder:

- According to Mahaparinibbana Sutta,[3] Gautama died in Kushinagar, which is located in present-day Uttar Pradesh, India.

-

- 411–400: Dundas 2002,

p. 24: “…as is now almost universally accepted by informed

Indological scholarship, a re-examination of early Buddhist historical

material, […], necessitates a redating of the Buddha’s death to

between 411 and 400 BCE…” - 405: Richard Gombrich[32] [33] [34] [35]

- Around 400: See the consensus in the essays by leading scholars in Narain, Awadh Kishore, ed. (2003), The Date of the Historical Śākyamuni Buddha, New Delhi: BR Publishing, ISBN 81-7646-353-1.

- According to Pali scholar K. R. Norman,

a life span for the Buddha of c. 480 to 400 BCE (and his teaching

period roughly from c. 445 to 400 BCE) “fits the archaeological evidence

better”.[2] See also Notes on the Dates of the Buddha Íåkyamuni.

- 411–400: Dundas 2002,

- According

to Alexander Berzin, “Buddhism developed as a shramana school that

accepted rebirth under the force of karma, while rejecting the existence

of the type of soul that other schools asserted. In addition, the

Buddha accepted as parts of the path to liberation the use of logic and

reasoning, as well as ethical behavior, but not to the degree of Jain

asceticism. In this way, Buddhism avoided the extremes of the previous

four shramana schools.”[18] - In 2013, archaeologist Robert Coningham found the remains of a Bodhigara, a tree shrine, dated to 550 BCE at the Maya Devi Temple, Lumbini, speculating that it may possible be a Buddhist shrine. If so, this may push back the Buddha’s birth date.[38] Archaeologists caution that the shrine may represent pre-Buddhist tree worship, and that further research is needed.[38]

Richard Gombrich has dismissed Coningham’s speculations as “a fantasy”,

noting that Coningham lacks the necessary expertise on the history of

early Buddhism.[39] Geoffrey Samuels notes that several locations of both early Buddhism and Jainism are closely related to Yaksha-worship, that several Yakshas were “converted” to Buddhism, a well-known example being Vajrapani,[40] and that several Yaksha-shrines, where trees were worshipped, were converted into Buddhist holy places.[41] - Some

sources mention Kapilavastu as the birthplace of the Buddha. Gethin

states: “The earliest Buddhist sources state that the future Buddha was

born Siddhārtha Gautama (Pali Siddhattha Gotama), the son of a local

chieftain — a rājan — in Kapilavastu (Pali Kapilavatthu) what is now the

Indian–Nepalese border.”[52] Gethin does not give references for this statement. - Minor

Rock Edict Nb3: “These Dhamma texts – Extracts from the Discipline, the

Noble Way of Life, the Fears to Come, the Poem on the Silent Sage, the

Discourse on the Pure Life, Upatisa’s Questions, and the Advice to

Rahula which was spoken by the Buddha concerning false speech – these

Dhamma texts, reverend sirs, I desire that all the monks and nuns may

constantly listen to and remember. Likewise the laymen and laywomen.”[59]

Dhammika:”There is disagreement amongst scholars concerning which Pali

suttas correspond to some of the text. Vinaya samukose: probably the

Atthavasa Vagga, Anguttara Nikaya, 1:98-100. Aliya vasani: either the

Ariyavasa Sutta, Anguttara Nikaya, V:29, or the Ariyavamsa Sutta,

Anguttara Nikaya, II: 27-28. Anagata bhayani: probably the Anagata

Sutta, Anguttara Nikaya, III:100. Muni gatha: Muni Sutta, Sutta Nipata

207-221. Upatisa pasine: Sariputta Sutta, Sutta Nipata 955-975.

Laghulavade: Rahulavada Sutta, Majjhima Nikaya, I:421.”[59] - Kumar Singh, Nagendra (1997). “Buddha as depicted in the Purāṇas”. Encyclopaedia of Hinduism. 7. Anmol Publications. pp. 260–75. ISBN 978-81-7488-168-7. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- According to Geoffrey Samuel, the Buddha was born as a Kshatriya,[83]

in a moderate Vedic culture at the central Ganges Plain area, where the

shramana-traditions developed. This area had a moderate Vedic culture,

where the Kshatriyas were the highest varna, in contrast to the Brahmanic ideology of Kuru-Panchala, where the Brahmins had become the highest varna.[83] Both the Vedic culture and the shramana tradition contributed to the emergence of the so-called “Hindu-synthesis” around the start of the Common Era.[84] [83] - Scholars

have noted inconsistencies in the presentations of the Buddha’s

enlightenment, and the Buddhist path to liberation, in the oldest

sutras. These inconsistencies show that the Buddhist teachings evolved,

either during the lifetime of the Buddha, or thereafter. See: * Andre

Bareau (1963), Recherches sur la biographie du Buddha dans les

Sutrapitaka et les Vinayapitaka anciens, Ecole Francaise

d’Extreme-Orient * Schmithausen, On some Aspects of Descriptions or

Theories of ‘Liberating Insight’ and ‘Enlightenment’ in Early Buddhism *

K. R. Norman, Four Noble Truths * Tilman Vetter, The Ideas and Meditative Practices of Early Buddhism * Richard F. Gombrich (2006). How Buddhism Began: The Conditioned Genesis of the Early Teachings. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-19639-5., chapter four * Bronkhorst, Johannes (1993), The Two Traditions Of Meditation In Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, chapter 7 * Anderson, Carol (1999), Pain and Its Ending: The Four Noble Truths in the Theravada Buddhist Canon, Routledge - Waley

notes: suukara-kanda, “pig-bulb”; suukara-paadika, “pig’s foot” and

sukaresh.ta “sought-out by pigs”. He cites Neumann’s suggestion that if a

plant called “sought-out by pigs” exists then suukaramaddava can mean

“pig’s delight”. - The surviving portions of the scriptures of Sarvastivada, Mulasarvastivada, Mahisasaka, Dharmaguptaka and other schools,[132] [133] and the Chinese Agamas and other surviving portions of other early canons.

- Exemplary studies are the study on descriptions of “liberating insight” by Lambert Schmithausen,[138] the overview of early Buddhism by Tilmann Vetter,[135] the philological work on the four truths by K.R. Norman,[139] the textual studies by Richard Gombrich,[137] and the research on early meditation methods by Johannes Bronkhorst.[134]

- A well-known proponent of the first position is A.K. Warder

- According to A.K. Warder, in his 1970 publication “Indian Buddhism”

- A proponent of the second position is Ronald Davidson.

- Ronald

Davidson: “While most scholars agree that there was a rough body of

sacred literature (disputed)(sic) that a relatively early community

(disputed)(sic) maintained and transmitted, we have little confidence

that much, if any, of surviving Buddhist scripture is actually the word

of the historic Buddha.”[143] - Well-known

proponents of the third position are: * J.W. de Jong: “It would be

hypocritical to assert that nothing can be said about the doctrine of

earliest Buddhism […] the basic ideas of Buddhism found in the

canonical writings could very well have been proclaimed by him [the

Buddha], transmitted and developed by his disciples and, finally,

codified in fixed formulas.”[144]

* Johannes Bronkhorst: “This position is to be preferred to (ii) for

purely methodological reasons: only those who seek may find, even if no

success is guaranteed.”[140]

* Donald Lopez: “The original teachings of the historical Buddha are

extremely difficult, if not impossible, to recover or reconstruct.”[145] - Vetter:

“However, if we look at the last, and in my opinion the most important,

component of this list [the noble eightfold path], we are still dealing

with what according to me is the real content of the middle way,

dhyana-meditation, at least the stages two to four, which are said to be

free of contemplation and reflection. Everything preceding the eighth

part, i.e. right samadhi, apparently has the function of preparing for

the right samadhi.”[148] - Majjhima Nikaya 36

- Vetter:

“I am especially thinking here of MN 26 (I p.163,32; 165,15;166,35)

kimkusalagavesi anuttaram santivarapadam pariyesamano (searching for

that which is beneficial, seeking the unsurpassable, best place of

peace) and again MN 26 (passim), anuttaramyagakkhemam nibbiinam

pariyesati (he seeks the unsurpassable safe place, the nirvana).

Anuppatta-sadattho (one who has reached the right goal) is also a vague

positive expression in the Arhatformula in MN 35 (I p, 235), see chapter

2, footnote 3, Furthermore, satthi (welfare) is important in e.g. SN

2.12 or 2.17 or Sn 269; and sukha and rati (happiness), in contrast to

other places, as used in Sn 439 and 956. The oldest term was perhaps

amata (immortal, immortality) […] but one could say here that it is a

negative term.”[153] - Understanding of these marks helps in the development of detachment:

- “in

Sanskrit philosophical literature, ‘āstika’ means ‘one who believes in

the authority of the Vedas’, ’soul’, ‘Brahman’. (’nāstika’ means the

opposite of these).[163] [164]

- Cousins 1996, pp. 57–63.

- Norman 1997, p. 33.

- “Maha-parinibbana Sutta”, Digha Nikaya (16), Access insight, part 5

- Baroni 2002, p. 230.

- Boeree, C George. “An Introduction to Buddhism”. Shippensburg University. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- Warder 2000, p. 45.

- Laumakis 2008, p. 4.

- Skilton 2004, p. 41.

- Rawlinson, Hugh George. (1950) A Concise History of the Indian People, Oxford University Press. p. 46.

- Muller, F. Max. (2001) The Dhammapada And Sutta-nipata, Routledge (UK). p. xlvii. ISBN 0-7007-1548-7.

- India: A History. Revised and Updated,

by John Keay: “The date [of Buddha’s meeting with Bimbisara] (given the

Buddhist ’short chronology’) must have been around 400 BCE.” - Smith 1924, pp. 34, 48.

- Schumann 2003, pp. 1-5.

- Jayatilleke 1963, chpt. 1-3.

- Clasquin-Johnson, Michel. “Will the real Nigantha Nātaputta please stand up? Reflections on the Buddha and his contemporaries”. Journal for the Study of Religion. 28 (1): 100–114. ISSN 1011-7601.

- Walshe 1995, p. 268.

- Collins 2009, pp. 199–200.

- Berzin, Alexander (April 2007). “Indian Society and Thought before and at the Time of Buddha”. Study Buddhism. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- Nakamura 1980, p. 20.

- Wynne 2007, pp. 8–23, ch. 2.

- Warder 1998, p. 45.

- Roy 1984, p. 1.

- Roy 1984, p. 7.

- Carrithers 2001.

- Buswell 2003, p. 352.

- Lopez 1995, p. 16.

- Schumann 2003, pp. 10–13.

- Bechert 1991–1997.

- Ruegg 1999, pp. 82-87.

- Narain 1993, pp. 187-201.

- Prebish 2008, p. 2.

- Gombrich 1992.

- Narain 1993, pp. 187–201.

- Hartmann 1991.

- Gombrich 2000.

- Schumann 2003, p. xv.

- Wayman 1993, pp. 37–58.

- Vergano, Dan (25 November 2013). “Oldest Buddhist Shrine Uncovered In Nepal May Push Back the Buddha’s Birth Date”. National Geographic. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- Gombrich, Richard (2013), Recent discovery of “earliest Buddhist shrine” a sham?, Tricycle

- Tan, Piya (2009-12-21), Ambaṭṭha Sutta. Theme: Religious arrogance versus spiritual openness (PDF), Dharma farer

- Samuels 2010, pp. 140–52.

- Gombrich 1988, p. 49.

- Davids, Rhys, ed. (1878), Buddhist

birth-stories; Jataka tales. The commentary introd. entitled

Nidanakatha; the story of the lineage. Translated from V. Fausböll’s ed.

of the Pali text by TW Rhys Davids (new & rev. ed.) - “Lumbini, the Birthplace of the Lord Buddha”. UNESCO. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- “The Astamahapratiharya: Buddhist pilgrimage sites”. Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- Gethin 1998, p. 19.

- Mahāpātra 1977.

- Mohāpātra 2000, p. 114.

- Tripathy 2014.

- Hartmann 1991, pp. 38–39.

- Keown & Prebish 2013, p. 436.

- Gethin 1998, p. 14.

- Walsh 1995, p. 20.

- Nakamura 1980, p. 18.

- Srivastava 1979, pp. 61–74.

- Srivastava 1980, p. 108.

- Tuladhar 2002, pp. 1–7.

- Huntington 1986.

- Dhammika 1993.

- Bhikkhu, Thanissaro. “That the True Dhamma Might Last a Long Time: Readings Selected by King Asoka”. Access to Insight. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- “Ancient Buddhist Scrolls from Gandhara”. UW Press. Retrieved 4 September 2008.

- Fowler 2005, p. 32.

- Beal 1883.

- Cowell 1894.

- Willemen 2009.

- Olivelle, Patrick (2008). Life of the Buddha by Ashva-ghosha (1st ed.). New York: New York University Press. p. xix. ISBN 9780814762165.

- Karetzky 2000, p. xxi.

- Beal 1875.

- Swearer 2004, p. 177.

- Schober 2002, p. 20.

- Anålayo, The Buddha and Omniscience, Indian International Journal of Buddhist Studies, 2006, vol. 7 pp. 1–20.

- Tan, Piya (trans) (2010). “The Discourse to Sandaka (trans. of Sandaka Sutta, Majjhima Nikāya 2, Majjhima Paṇṇāsaka 3, Paribbājaka Vagga 6)” (PDF). The Dharmafarers. The Minding Centre. pp. 17–18. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- MN 71 Tevijjavacchagotta [Tevijjavaccha]

- Access to Insight, ed. (2005). “A Sketch of the Buddha’s Life: Readings from the Pali Canon”. Access to Insight: Readings in Theravāda Buddhism. Access to Insight (Legacy Edition). Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- Jones 1956.

- Skilton 2004, p. 64-65.

- Carrithers 2001, p. 15.

81) Classical Serbian

81) Класични српски

2436 Пет 10 Нов 2017 ЛЕКЦИЈА

Типитака

Типитака (Пали ти, “три”, питака, “корпе”),

или Пали канон, је колекција примарних текстова Пали језика који су

формирају доктринарну основу Тхеравадског будизма. Типитака и

паракононски пали текстови (коментари, хронике, итд.) заједно чине комплетно тело класичних текстова Тхеравада.

Тхе

Пали канон је огромно тело књижевности: у преводу на енглески језик

текстови додају хиљаде штампаних страница. Већина (али не и све)

Цанон је већ објављен на енглеском преко година. Иако

само мали део ових текстова је доступан на овој веб страници, ово

колекција може бити добро место за почетак.

Три одјела Типитаке су:

Винаиа Питака

Збирка текстова који се тичу правила понашања која се односе на

дневне послове унутар Сангхе - заједница бхиккхуса (ордаинед монкс) и

бхиккхунис (ордаинед

монахиње). Далеко више од само правила, Винаиа Питака такође

укључује приче иза извора сваког правила, а

детаљан приказ Будиног рјешења за питање како

одржавају заједничку хармонију унутар великог и разноликог духовног

заједница.

Сутта Питака

Тхе

збирка сутата или дискурса, приписаних Буди и неколико

његових најближих ученика, који садрже сва централна учења

Тхеравада будизам. (Више од хиљаду превода сутте су

доступне на овој веб страници.) Сутате су подељене међу пет никаиас (колекције):

Дигха Никаиа - “дуга колекција”

Мајјхима Никаиа - “колекција средњих дужина”

Самиутта Никаиа - “груписана колекција”

Ангуттара Никаиа - “додатна збирка”

Кхуддака Никаиа - “збирка малих текстова”:

Кхуддакапатха

Дхаммапада

Удана

Итивуттака

Сутта Нипата

Виманаваттху

Петаваттху

Тхерагатха

Тхеригатха

Јатака

Ниддеса

Патисамбхидамагга

Ападана

Буддхавамса

Царииапитака

Неттипакарана (укључен само у бурманско издање Типитаке)

Петакопадеса (”")

Милиндапанха (”")

Абхидхамма Питака

Тхе

збирка текстова у којима су основни принципи доктрине

представљени у Сутта Питаки су преобликовани и реорганизовани у а

систематски оквир који се може применити на истрагу о

природа ума и материје.

Life Sketch of Savitribai Phule – Timeline

http://velivada.com/life-sketch-of-savitribai-phule-timeline/

Life Sketch of Savitribai Phule – Timeline

“Savitribai Phule (1831-97), struggled and suffered with her

revolutionary husband in an equal measure, but remains obscured due to

casteist and sexist negligence. Apart from her identity as Jotirao

Phule’s wife, she is little known even in academia. Modern India’s first

woman teacher, a radical exponent of mass and female education, a

champion of women’s liberation, a pioneer of engaged poetry, a

courageous mass leader who took on the forces of caste and patriarchy

certainly had her independent identity and contribution. It is indeed a

measure of the ruthlessness of elite-controlled knowledge-production

that a figure as important as Savitribai Phule fails to find any mention

in the history of modern India. Her life and struggle deserves to be

appreciated by a wider spectrum, and made known to non-Marathi people as

well,” writes Braj Ranjan Mani.

Here we present life-sketch of Savitribai Phule. In case we have

missed any important event from the life of Savitribai Phule or have

made any mistake while recording any event, let us know in the comments

section and we will try to update the timeline. Alternatively, you can

submit further information here. If you like this timeline, share it with your friends!

Savitribai Phule

Savitribai Phule Google Doodle

2436 Fri 10 Nov 2017 LESSON

2436 Fri 10 Nov 2017 LESSON

http://velivada.com/life-sketch-of-savitribai-phule-timeline/

Life Sketch of Savitribai Phule – Timeline

“Savitribai Phule (1831-97), struggled and suffered with her

revolutionary husband in an equal measure, but remains obscured due to

casteist and sexist negligence. Apart from her identity as Jotirao

Phule’s wife, she is little known even in academia. Modern India’s first

woman teacher, a radical exponent of mass and female education, a

champion of women’s liberation, a pioneer of engaged poetry, a

courageous mass leader who took on the forces of caste and patriarchy

certainly had her independent identity and contribution. It is indeed a

measure of the ruthlessness of elite-controlled knowledge-production

that a figure as important as Savitribai Phule fails to find any mention

in the history of modern India. Her life and struggle deserves to be

appreciated by a wider spectrum, and made known to non-Marathi people as

well,” writes Braj Ranjan Mani.

Here we present life-sketch of Savitribai Phule. In case we have

missed any important event from the life of Savitribai Phule or have

made any mistake while recording any event, let us know in the comments

section and we will try to update the timeline. Alternatively, you can

submit further information here. If you like this timeline, share it with your friends!

Savitribai Phule

On 3 January 2017, the search engine Google marked the 186th birth anniversary of Savitribai Phule with a Google doodle.