Posted by: site admin @ 12:36 am

is our pleasure to welcome you all to Mangaluru, Karnataka for the 17th

Masters National Championships 2021 to be held at from 26th to 28th

November 2021.

|

Verse 179. The Buddha Cannot Be Tempted

Explanation: The Buddha’s victory has not been won incorrectly. |

|

Verse 180. The Buddha Cannot Be Brought Under Sway

Explanation: The Buddha, in whom there is no thirst (tanha) |

|

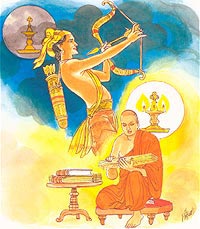

Verse 181. Gods And Men Adore The Buddha

Explanation: Those noble and wise ones are intent on meditation. |

|

Verse 182. Four Rare Opportunities

Explanation: It is rare that one is born a human being, in |

|

Verse 183. The Instructions Of The Buddha

Explanation: Abandoning all evil and purifying one’s |

|

Verse 184. Patience Is A Great Ascetic Virtue

Explanation: Enduring patience is the highest asceticism. |

|

Verse 185. Noble Guidelines

Explanation: To refrain from finding fault with others; to |

|

Verse 186. Sensual Pleasures Never Satiated

Explanation: Insatiable are sensual desires. Sensual desires |

|

Verse 187. Shun Worldly Pleasures

Explanation: The discipline of the Buddha does not even go |

|

Verse 188. Fear Stricken Masses

Explanation: Human beings who tremble in fear seek refuge |

|

Verse 189. Those Refuges Do Not Help

Explanation: These are not secure refuges. The are not the |

|

Verse 190. Seeing Four Noble Truths

Explanation: If a wise person were to take |

|

Verse 191. The Noble Path

Explanation: The four extraordinary realities are suffering; |

|

Verse 192 The Refuge That Ends All Suffering

Explanation: This refuge in the Triple Refuge is, of course, |

|

Verse 193. Rare Indeed Is Buddha’s Arising

Explanation: The Buddha is rare indeed. Such a rare person |

|

Verse 194. Four Factors of Happiness

Explanation: The arising of the Buddha is joyful. The proclamation |

|

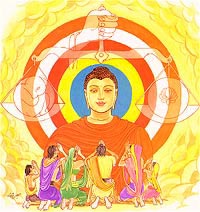

Verse 195. Worship Those Who Deserve Adoration

Explanation: Those who have gone beyond apperception ( the |

|

Verse 196. Worship Brings Limitless Merit

Explanation: One who worships those who have attained imperturbability |

|

Verse 198. Without Sickness Among The Sick

Explanation: Among those sick, afflicted by defilements, we, |

|

Verse 199. Not Anxious Among The Anxious

Explanation: Among the anxious men and women, who ceaselessly |

|

Verse 200. Happily They Live - Undefiled

Explanation: Happily we live, who have no property to worry |

|

Verse 201. Happy About Both Victory And Defeat

Explanation: Victory brings hatred into being. The defeated |

|

Verse 202. Happiness Tranquilizes

Explanation: There is no fire like passion. There is no crime |

|

Verse 203. Worst Disease And Greatest Happiness

Explanation: The most severe disease is hunger. The worst |

|

Verse 204. Four Supreme Acquisitions

Explanation: Of acquisitions, good health is the foremost. |

|

Verse 205. The Free Are The Purest

Explanation: He has savoured the taste of solitude. He has |

|

Verse 206. Pleasant Meetings

Explanation: Seeing nobles ones is good. Living with them |

|

Verse 207. Happy Company

Explanation: A person who keeps company with the ignorant |

|

Verse 208. The Good And The Wise

Explanation: The moon keeps to the path of the stars. In exactly |

|

Verse 197. Happiness

Explanation: Among those who hate, we live without hating, |

|

Verse 209. Admiration of Self-Seekers

Explanation: Being devoted to what is wrong, not being devoted |

|

Verse 210. Not Seeing The Liked And Seeing The Unliked Are Both Painful

Explanation: Never associate with those whom you like, as |

|

Verse 211. Not Bound By Ties Of Defilements

Explanation: Therefore, one must not have endearments; because |

|

Verse 212. The Outcome Of Endearment

Explanation: From endearment arises sorrow. From endearment |

|

Verse 213. Sorrow And Fear Arise Due To Loved Ones

Explanation: From affection sorrow arises. From affection |

|

Verse 214. The Outcome Of Passion

Explanation: From passion arises sorrow. From passion fear |

|

Verse 215. The Outcome Of Lust

Explanation: From desire arises sorrow. From desire fear arises. |

|

Verse 216. Sorrow And Fear Arise Due To Miserliness

Explanation: From craving arises sorrow. From craving fear |

|

Verse 217. Beloved Of The Masses

Explanation: He is endowed with discipline and insight. He |

|

Verse 218. The Person With Higher Urges

Explanation: In that person a deep yearning for the undefined |

|

Verse 219. The Fruits Of Good Action

Explanation: When a person, who has lived away from home for |

|

Verse 220. Good Actions Lead To Good Results

Explanation: In the same way, when those who have done meritorious |

|

Verse 222. The Efficient Charioteer

Explanation: That person who is capable of curbing sudden |

|

Verse 223. Four Forms Of Victories

Explanation: Let anger be conquered by love. Let bad be conquered |

|

Verse 224. Three Factors Leading To Heaven

Explanation: Speak the truth. Do not get angry. When asked, |

|

Verse 225. Those Harmless One Reach The Deathless

Explanation: Those harmless sages, perpetually restrained |

|

Verse 226. Yearning For Nibbana

Explanation: Of those who are perpetually wakeful - alert, |

|

Verse 227. There Is No One Who Is Not Blamed

Explanation: O’ Atula, This has been said in the olden |

|

Verse 228. No One Is Exclusively Blamed Or Praised

Explanation: There was never a person who was wholly, totally |

|

Verse 229. Person Who Is Always Praise-Worthy

Explanation: But those whom the wise praise, after a daily |

|

Verse 230. Person Who Is Like Solid Gold

Explanation: A person of distinction is beyond blame or praise |

|

Verse 231. The Person Of Bodily Discipline

Explanation: Guard against the physical expression of emotions. |

|

Verse 232. Virtuous Verbal Behaviour

Explanation: Guard against the verbal expression of emotions. |

|

Verse 233. Discipline Your Mind

Explanation: Guard against the mental expression of emotions. |

|

Verse 234. Safeguard The Three Doors

Explanation: The wise are restrained in body. They are restrained |

|

Verse 221. He Who Is Not Assaulted By Sorrow

Explanation: Abandon anger. Give up pride fully. Get rid of |

|

Verse 236. Get Immediate Help

Explanation: As things are, be a lamp, an island, a refuge |

|

Verse 237. In The Presence Of King Of Death

Explanation: Now, your allotted life span is spent. You have |

|

Verse 238. Avoid The Cycle Of Existence

Explanation: Therefore, become a lamp, an island, a refuge |

|

Verse 239. Purify Yourself Gradually

Explanation: Wise persons, moment by moment, little by little, |

|

Verse 240. One’s Evil Ruins One’s Own Self

Explanation: The rust springing from iron, consumes the iron |

|

Verse 241. Causes Of Stain

Explanation: For formulas that have to be memorized, non repetition |

|

Verse 242. Ignorance Is The Greatest Taint

Explanation: For mankind, misconduct is the blemish. For charitable |

|

Verse 243. Ignorance The Worst Taint

Explanation: Monks, there is a worst blemish than all these |

|

Verse 244. The Shameless Life Is Easy

Explanation: If an individual possesses no sense of shame, |

|

Verse 245. For A Modest Person Life Is Hard

Explanation: The life is hard for a person who is modest, |

|

Verse 246. Wrong Deeds To Avoid

Explanation: One day a group of lay disciples who only kept |

|

Verse 247. Precepts The Lay Person Should Follow

Explanation: A man who is given to taking intoxicating drinks, |

|

Verse 248. These Precepts Prevent Suffering

Explanation: Evil actions do not have restraint or discipline. |

|

Verse 249. The Envious Are Not At Peace

Explanation: The people give in terms of the faith they have |

|

Verse 250. The Unenvious Are At Peace

Explanation: If someone were to utterly uproot and totally |

|

Verse 251. Craving Is The Worst Flood

Explanation: There is no fire life passion. There is no grip |

|

Verse 252. Easy To See Are The Faults Of Others

Explanation: The faults of others are clearly observed. But |

|

Verse 253. Seeing Others’ Faults

Explanation: There are those who are given to the habit of |

|

Verse 254. Nothing Is Eternal Other Than Nibbana

Explanation: In the skies, there are no footsteps that can |

|

Verse 255. The Buddha Has No Anxiety

Explanation: In the skies, there is no footsteps that can |

|

Verse 235. Man At The Door Of Death

Explanation: Now you are like a withered, yellowed dried leaf. |

|

Verse 257. Firmly Rooted In The Law

Explanation: That wise person, who dispenses justice and judges |

|

Verse 258. Who Speaks A Lot Is Not Necessarily Wise

Explanation: A person cannot be described as learned simply |

|

Verse 259. Those Who Know Speak Little

Explanation: One does not become an upholder of the Law of |

|

Verse 260. Grey Hair Alone Does Not Make An Elder

Explanation: One does not become an elder merely because one’s |

|

Verse 261. The Person Full Of Effort Is The True Elder

Explanation: All things that men do arise out of the mind. |

|

Verse 262. Who Gives Up Jealousy Is Good-Natured

Explanation: Merely because of one’s verbal flourishes, |

|

Verse 263. Who Uproots Evil Is The Virtuous One

Explanation: If an individual has uprooted and eradicated |

|

Verse 264. Shaven Head Alone Does Not Make A Monk

Explanation: Can an individual who does not practice religion, |

|

Verse 265. Who Give Up Evil Is True Monk

Explanation: If an individual were to quell all defilements, |

|

Verse 266. One Is Not A Monk Merely By Begging Alms Food

Explanation: No one becomes a monk merely because he begs |

|

Verse 267. The Holy Life Makes a Monk

Explanation: Who rises above both good and evil and treads |

|

Verse 268. Silence Alone Does Not Make A Sage

Explanation: The ignorant person, possessing foolish ways |

|

Verse 269. Only True Wisdom Makes a Sage

Explanation: Weighing what is right and wrong, he shuns evil. |

|

Verse 270. True Ariyas Are Harmless

Explanation: A person who hurts living beings is not a noble |

|

Verse 271. A Monk Should Destroy All Passions

Explanation: These two stanzas are an admonition to the monks |

|

Verse 272. Blemishes Should Be Given Up To Reach Release

Explanation: Monks, do not rest content by precepts and rites. |

|

Verse 256. The Just And The Impartial Judge Best

Explanation: If for some reason someone were to judge what |

How investigating the causes for the arising of the sense

organs, for which in this case the characteristic of nonself may be

easier to understand, allows a transfer of this understanding to their

case.

Pāḷi |

English |

|

cakkhuṃ, bhikkhave, anattā. yo·pi hetu, yo·pi paccayo cakkhussa uppādāya, so·pi anattā. anatta·sambhūtaṃ, bhikkhave, cakkhu kuto attā bhavissati? |

|

|

sotaṃ anattā. yo·pi hetu yo·pi paccayo sotassa uppādāya, so·pi anattā. anatta·sambhūtā, bhikkhave, sotaṃ kuto attā bhavissati? |

|

|

ghāṇaṃ anattā. yo·pi hetu yo·pi paccayo ghāṇassa uppādāya, so·pi anattā. anatta·sambhūtā, bhikkhave, ghāṇaṃ kuto attā bhavissati? |

|

|

jivhā anattā. yo·pi hetu yo·pi paccayo jivhāya uppādāya, so·pi anattā. anatta·sambhūtā, bhikkhave, jivhā kuto attā bhavissati? |

|

|

kāyo anattā. yo·pi hetu yo·pi paccayo kāyassa uppādāya, so·pi anattā. anatta·sambhūtā, bhikkhave, kāyo kuto attā bhavissati? |

|

|

mano anattā. yo·pi hetu yo·pi paccayo manassa uppādāya, so·pi anattā. anatta·sambhūto, bhikkhave, mano kuto attā bhavissati? |

|

|

evaṃ passaṃ, bhikkhave, sutavā ariya·sāvako cakkhusmiṃ·pi nibbindati, sotasmiṃ·pi nibbindati, ghāṇasmiṃ·pi nibbindati, jivhāyaṃ·pi nibbindati, kāyasmiṃ·pi nibbindati, manasi·pi nibbindati; nibbindaṃ virajjati; virāgā vimuccati; vimuttasmiṃ ‘vimuttami‘ti ñāṇaṃ hoti; ‘khīṇā jāti, vusitaṃ brahmacariyaṃ, kataṃ karaṇīyaṃ, n·āparaṃ itthattāyā’ ti pajānātī·ti. |

|

The mind can be our worst enemy or our best friend.

Pāḷi

|

English

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Speaking rightly, what should be called ‘accumulation of demerit’?

Pāḷi |

English |

|

|

|

The Buddha reminds the monks that the practice of Dhamma should

not be put off for a later date, for there are no guarantees that the

future will provide any opportunities for practice.

Pāḷi

|

English“Monks, these five future dangers, unarisen at present, will arise in |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The famous sutta about the practice of ānāpānassati, and how it

leads to the practice of the four satipaṭṭhānas and subsquently to the

fulfillment of the seven bojjhaṅgas.

In this very famous sutta, the Buddha expounds for the first time his teaching on anatta.

| 1) info·bubbles on every Pali word 2) there is some uncertainty over the declension ending of some words in the Pali text, but that should not affect the reader’s experience. |

Pāḷi |

English |

|

Ekaṃ samayaṃ bhagavā bārāṇasiyaṃ viharati isipatane miga·dāye. Tatra kho bhagavā pañca·vaggiye bhikkhū āmantesi: |

|

|

– Bhadante ti te bhikkhū bhagavato paccassosuṃ. Bhagavā etad·avoca: |

– Bhadante, the bhikkhus replied. The Bhagavā said: |

|

|

|

|

Vedanā anattā. Vedanā ca h·idaṃ, bhikkhave, attā abhavissa, na·y·idaṃ vedanā ābādhāya saṃvatteyya, labbhetha ca vedanāya: ‘evaṃ me vedanā hotu, evaṃ me vedanā mā ahosī’ti. Yasmā ca kho, bhikkhave, vedanā anattā, tasmā vedanā ābādhāya saṃvattati, na ca labbhati vedanāya: ‘evaṃ me vedanā hotu, evaṃ me vedanā mā ahosī’ti. |

Vedanā, bhikkhus, is anatta. And if this vedanā were atta, bhikkhus, this vedanā would not lend itself to dis·ease, and it could [be said] of vedanā: ‘Let my vedanā be thus, let my vedanā not be thus.’ But it is because vedanā is anatta that vedanā lends itself to dis·ease, and that it cannot [be said] of vedanā: ‘Let my vedanā be thus, let my vedanā not be thus.’ |

|

Saññā bhikkhave, anattā, saññañ·ca h·idaṃ bhikkhave, attā abhavissa na·y·idaṃ saññaṃ ābādhāya saṃvatteyya, labbhetha ca saññāya: ‘evaṃ me saññā hotu, evaṃ me saññaṃ mā ahosī’ti. Yasmā ca kho bhikkhave, saññaṃ anattā, tasmā saññaṃ ābādhāya saṃvattati, na ca labbhati saññāya: ‘evaṃ me saññā hotu, evaṃ me saññaṃ mā ahosī’ti. |

Saññā, bhikkhus, is anatta. And if this saññā were atta, bhikkhus, this saññā would not lend itself to dis·ease, and it could [be said] of saññā: ‘Let my saññā be thus, let my saññā not be thus.’ But it is because saññā is anatta that saññā lends itself to dis·ease, and that it cannot [be said] of saññā: ‘Let my saññā be thus, let my saññā not be thus.’ |

|

Saṅkhārā bhikkhave, anattā, saṅkhārañ·ca h·idaṃ bhikkhave, attā abhavissa na·y·idaṃ saṅkhāraṃ ābādhāya saṃvatteyya, labbhetha ca saṅkhāresu: ‘evaṃ me saṅkhāraṃ hotu, evaṃ me saṅkhāraṃ mā ahosī’ti. Yasmā ca kho bhikkhave, saṅkhāraṃ anattā, tasmā saṅkhāraṃ ābādhāya saṃvattati, na ca labbhati saṅkhāresu: ‘evaṃ me saṅkhāraṃ hotu, evaṃ me saṅkhāraṃ mā ahosī’ti. |

Saṅkhāras, bhikkhus, are anatta. And if these saṅkhāras were atta, bhikkhus, these saṅkhāras would not lend themselves to dis·ease, and it could [be said] of saṅkhāras: ‘Let my saṅkhāras be thus, let my saṅkhāras not be thus.’ But it is because saṅkhāras are anatta that saṅkhāras lend themselves to dis·ease, and that it cannot [be said] of saṅkhāras: ‘Let my saṅkhāras be thus, let my saṅkhāras not be thus.’ |

|

Viññāṇaṃ bhikkhave, anattā, viññāṇañ·ca h·idaṃ bhikkhave, attā abhavissa na·y·idaṃ viññāṇaṃ ābādhāya saṃvatteyya, labbhetha ca viññāṇe: ‘evaṃ me viññāṇaṃ hotu, evaṃ me viññāṇaṃ mā ahosī’ti. Yasmā ca kho bhikkhave, viññāṇaṃ anattā, tasmā viññāṇaṃ ābādhāya saṃvattati, na ca labbhati viññāṇe: ‘evaṃ me viññāṇaṃ hotu, evaṃ me viññāṇaṃ mā ahosī’ti. |

Viññāṇa, bhikkhus, is anatta. And if this viññāṇa were atta, bhikkhus, this viññāṇa would not lend itself to dis·ease, and it could [be said] of viññāṇa: ‘Let my viññāṇa be thus, let my viññāṇa not be thus.’ But it is because viññāṇa is anatta that viññāṇa lends itself to dis·ease, and that it cannot [be said] of viññāṇa: ‘Let my viññāṇa be thus, let my viññāṇa not be thus.’ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

– Yaṃ pan·āniccaṃ dukkhaṃ vipariṇāma·dhammaṃ, kallaṃ nu taṃ samanupassituṃ: ‘etaṃ mama, eso·ham·asmi, eso me attā’ti? |

– And that which is anicca, dukkha, by nature subject to change, is it proper to regard it as: ‘This is mine. I am this. This is my atta?’ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

– Yaṃ pan·āniccaṃ dukkhaṃ vipariṇāma·dhammaṃ, kallaṃ nu taṃ samanupassituṃ: ‘etaṃ mama, eso·ham·asmi, eso me attā’ti? |

– And that which is anicca, dukkha, by nature subject to change, is it proper to regard it as: ‘This is mine. I am this. This is my atta?’ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

– Yaṃ pan·āniccaṃ dukkhaṃ vipariṇāma·dhammaṃ, kallaṃ nu taṃ samanupassituṃ: ‘etaṃ mama, eso·ham·asmi, eso me attā’ti? |

– And that which is anicca, dukkha, by nature subject to change, is it proper to regard it as: ‘This is mine. I am this. This is my atta?’ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

– Yaṃ pan·āniccaṃ dukkhaṃ vipariṇāma·dhammaṃ, kallaṃ nu taṃ samanupassituṃ: ‘etaṃ mama, eso·ham·asmi, eso me attā’ti? |

– And that which is anicca, dukkha, by nature subject to change, is it proper to regard it as: ‘This is mine. I am this. This is my atta?’ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

– Yaṃ pan·āniccaṃ dukkhaṃ vipariṇāma·dhammaṃ, kallaṃ nu taṃ samanupassituṃ: ‘etaṃ mama, eso·ham·asmi, eso me attā’ti? |

– And that which is anicca, dukkha, by nature subject to change, is it proper to regard it as: ‘This is mine. I am this. This is my atta?’ |

|

– Tasmātiha, bhikkhave, yaṃ kiñci rūpaṃ atīt·ānāgata·paccuppannaṃ ajjhattaṃ vā bahiddhā vā oḷārikaṃ vā sukhumaṃ vā hīnaṃ vā paṇītaṃ vā yaṃ dūre santike vā, sabbaṃ rūpaṃ ‘n·etaṃ mama, n·eso·ham·asmi, na m·eso attā’ti evam·etaṃ yathā·bhūtaṃ samma·p·paññāya daṭṭhabbaṃ. |

– Therefore, bhikkhus, whatever rūpa, be it past, future, or present, internal or external, gross or subtle, inferior or exalted, far or near, any rūpa is to be seen yathā·bhūtaṃ with proper paññā in this way: ‘This is not mine, I am not this, this is not my atta.’ |

|

Yā kāci vedanā atīt·ānāgata·paccuppannā ajjhattā vā bahiddhā vā oḷārikā vā sukhumā vā hīnā vā paṇītā vā, yaṃ dūre santike vā sabbā vedanā ‘n·etaṃ mama, n·eso·ham·asmi, na m·eso attā’ti evam·etaṃ yathā·bhūtaṃ samma·p·paññāya daṭṭhabbaṃ. |

|

|

Yā kāci saññā atīt·ānāgata·paccuppannā, ajjhattā vā bahiddhā vā oḷārikā vā sukhumā vā hīnā vā paṇītā vā, yaṃ dūre santike vā sabbā saññā ‘n·etaṃ mama, n·eso·ham·asmi, na m·eso attā’ti evam·etaṃ yathā·bhūtaṃ samma·p·paññāya daṭṭhabbaṃ. |

|

|

Ye keci saṅkhārā atīt·ānāgata·paccuppannā, ajjhattā vā bahiddhā vā oḷārikā vā sukhumā vā hīnā vā paṇītā vā, yaṃ dūre santike vā sabbā saṅkhārā ‘n·etaṃ mama, n·eso·ham·asmi, na m·eso attā’ti evam·etaṃ yathā·bhūtaṃ samma·p·paññāya daṭṭhabbaṃ. |

|

|

Yaṃ kiñci viññāṇaṃ atīt·ānāgata·paccuppannaṃ, ajjhattaṃ vā bahiddhā vā oḷārikaṃ vā sukhumaṃ vā hīnaṃ vā paṇītaṃ vā, yaṃ dūre santike vā sabbaṃ viññāṇaṃ ‘n·etaṃ mama, n·eso·ham·asmi, na m·eso attā’ti evam·etaṃ yathā·bhūtaṃ samma·p·paññāya daṭṭhabbaṃ. |

|

|

Evaṃ passaṃ, bhikkhave, sutavā ariyasāvako rūpasmim·pi nibbindati, vedanāya·pi nibbindati, saññāya·pi nibbindati, saṅkhāresu·pi nibbindati, viññāṇasmim·pi nibbindati. Nibbindaṃ virajjati. Virāgā vimuccati. Vimuttasmiṃ ‘vimuttami’ti ñāṇaṃ hoti. ‘Khīṇā jāti, vusitaṃ brahmacariyaṃ, kataṃ karaṇīyaṃ, n·āparaṃ itthattāyā’ti pajānātī·ti. |

|

|

Idam·avoca bhagavā. Attamanā pañca·vaggiyā bhikkhū bhagavato bhāsitaṃ abhinanduṃ. |

|

|

Imasmiñ·ca pana veyyākaraṇasmiṃ bhaññamāne pañca·vaggiyānaṃ bhikkhūnaṃ anupādāya āsavehi cittāni vimucciṃsūti. |

|