For The Welfare, Happiness, Peace of All Sentient and Non-Sentient Beings and for them to Attain Eternal Peace as Final Goal. at

KUSHINARA NIBBANA BHUMI PAGODA-is a 18 feet Dia All White Pagoda with a table or, but be sure to having above head level based on the usual use of the room.

in 116 CLASSICAL LANGUAGES and planning to project Therevada Tipitaka in

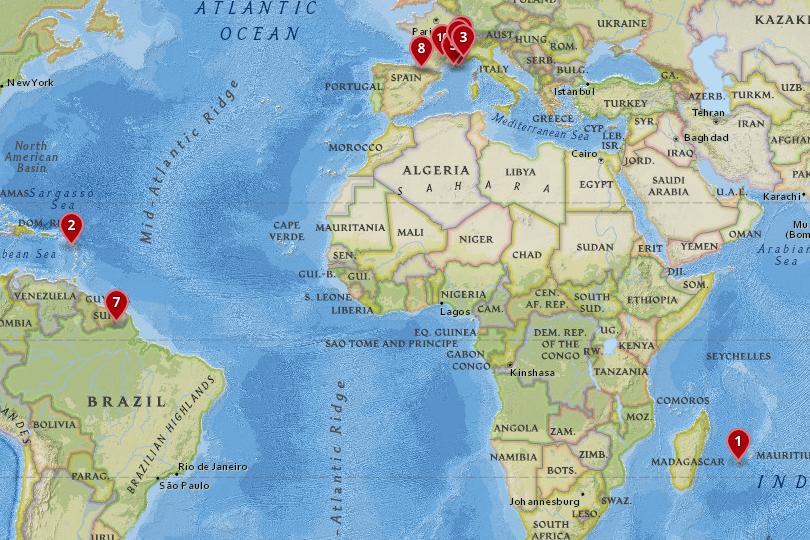

Buddha’s own words and Important Places like Lumbini, Bodh

gaya,Saranath, Kushinara, Etc., in 3D 360 degree circle vision akin to

Circarama

When

you are in Bengaluru you are most welcome to visit Kushinara Nibbana Bhumi Pagoda

At

WHITE HOME

668, 5A main Road, 8th Cross, HAL III Stage,

Prabuddha Bharat Puniya Bhumi Bengaluru

Magadhi Karnataka State

PRABUDDHA BHARAT

May you, your family members and all sentient and non sentient beings be ever happy, well and secure!

May all live for 150 years

with NAD pills to be available in 2020 at a price of a cup of coffee

according to research doctors at Sydney!

May all have calm, quiet, alert and attentive and have equanimity mind with a clear understanding that everything is changing!

Suttas word by word

10 Famous Buddha Statues

09) Classical Albanian-Shqiptare klasike,

10) Classical Amharic-አንጋፋዊ አማርኛ,

11) Classical Arabic-اللغة العربية الفصحى

12) Classical Armenian-դասական հայերեն,

13) Classical Azerbaijani- Klassik Azərbaycan,14) Classical Basque- Euskal klasikoa,

15) Classical Belarusian-Класічная беларуская,

16) Classical Bengali-ক্লাসিক্যাল বাংলা,

17) Classical Bosnian-Klasični bosanski,

18) Classical Bulgaria- Класически българск,19) Classical Catalan-Català clàssic

20) Classical Cebuano-Klase sa Sugbo,

21) Classical Chichewa-Chikale cha Chichewa,

22) Classical Chinese (Simplified)-古典中文(简体),

23) Classical Chinese (Traditional)-古典中文(繁體),

24) Classical Corsican-Corsa Corsicana,

25) Classical Croatian-Klasična hrvatska,

26) Classical Czech-Klasická čeština,27) Classical Danish-Klassisk dansk,Klassisk dansk,

28) Classical Dutch- Klassiek Nederlands,30) Classical Esperanto-Klasika Esperanto,

31) Classical Estonian- klassikaline eesti keel,

32) Classical Filipino klassikaline filipiinlane,

33) Classical Finnish- Klassinen suomalainen,

34) Classical French- Français classique,

35) Classical Frisian- Klassike Frysk,

SN 22.59 (S iii 66)

Anattalakkhana Sutta

- Die kenmerk van geen-self -

[anattā · lakkhaṇa]

In hierdie baie bekende sutta lê die Boeddha vir die eerste keer sy onderrig oor anatta uit.

By

een geleentheid het die Bhagavā in Bārāṇasi in die Deer Grove in

Isipatana gebly. Daar het hy die groep van vyf bhikkhus toegespreek:

- Bhikkhus.

- Bhadante, antwoord die bhikkhus. Die Bhagavā het gesê:

-

Rūpa, bhikkhus, is anatta. En as hierdie rûpa atta, bhikkhus was, sou

hierdie rûpa hom nie verlig nie, en van rûpa kon gesê word: ‘Laat my

rûpa so wees, laat my rûpa nie so wees nie.’ Maar dit is omdat rûpa

anatta is wat rûpa hom toelaat om te verswak, en dat dit nie van rûpa

gesê kan word nie: ‘Laat my rûpa so wees, laat my rûpa nie so wees nie.’

Vedanā,

bhikkhus, is anatta. En as hierdie vedanā atta, bhikkhus, sou hierdie

vedanā hom nie verleent nie, en van vedanā kon gesê word: ‘Laat my

vedana so wees, laat my vedanā nie so wees nie.’ Maar omdat vedanā ‘n

anatta is, leen vedanā hom tot ongemak, en kan dit nie van vedanā gesê

word nie: ‘Laat my vedanā so wees, laat my vedanā nie so wees nie.’

Saññā,

bhikkhus, is anatta. En as hierdie saññā atta, bhikkhus was, sou

hierdie saññā hom nie verlig nie, en van saññā kon gesê word: ‘Laat my

saññā so wees, laat my saññā nie so wees nie.’ Maar dit is omdat saññā

‘n anatta is wat saññā hom verlig en dat dit nie van saññā gesê kan word

nie: ‘Laat my saññā so wees, laat my saññā nie so wees nie.’

Saṅkhāras,

bhikkhus, is anatta. En as hierdie saṅkhāras atta, bhikkhus was, sou

hierdie saṅkhāras hulle nie verleen nie, en van saṅkhāras kon daar gesê

word: ‘Laat my saṅkhāras so wees, laat my saṅkhāras nie so wees nie.’

Maar dit is omdat saṅkhāras ‘n anatta is wat saṅkhāras hulself verlig,

en dat dit nie van saṅkhāras gesê kan word nie: ‘Laat my saṅkhāras so

wees, laat my saṅkhāras nie so wees nie.’

Viññāṇa, bhikkhus, is

anatta. En as hierdie viññāṇa atta, bhikkhus was, sou hierdie viññāṇa

hom nie verlig nie, en daar kon van viññāṇa gesê word: ‘Laat my viññāṇa

so wees, laat my viññāṇa nie so wees nie.’ Maar dit is omdat viññāṇa ‘n

anatta is wat viññā la hom toelaat om te verswak, en dat dit nie van

viññāṇa gesê kan word nie: ‘Laat my viññāṇa so wees, laat my viññāṇa nie

so wees nie.’

Wat dink u hiervan, bhikkhus: is Rūpa permanent of anicca?

tydelik

- Anicca, Bhanthdhe

- En wat anicca is, is dit dukkha of sukha? {1}

- Dukkha, Bhante.

-

En dit wat anicca, dukkha, van nature onderhewig is aan verandering, is

dit gepas om dit te beskou as: ‘Dit is myne. Ek is dit. Dit is my atta?

‘

- Nee, Bhante.

- Is Vedanā permanent of anicca?

- Anicca, Bhante.

- En dit wat anicca is, is dit dukkha of sukha?

- Dukkha, Bhante.

-

En dit wat anicca, dukkha, van nature onderhewig is aan verandering, is

dit gepas om dit te beskou as: ‘Dit is myne. Ek is dit. Dit is my atta?

‘

- Nee, Bhante.

- Is Saññā permanent of anicca?

- Anicca, Bhante.

- En dit wat anicca is, is dit dukkha of sukha?

- Dukkha, Bhante.

-

En dit wat anicca, dukkha, van nature onderhewig is aan verandering, is

dit gepas om dit te beskou as: ‘Dit is myne. Ek is dit. Dit is my atta?

‘

- Nee, Bhante.

- Is Saṅkhāras permanent of anicca?

- Anicca, Bhante.

- En dit wat anicca is, is dit dukkha of sukha?

-

En wat anicca, dukkha, van nature onderhewig is aan verandering, is dit

gepas om dit te beskou as: ‘Dit is myne. Ek is dit. Dit is my atta? ‘

- Nee, Bhante.

- Is Viññāṇa permanent of anicca?

- Anicca, Bhante.

- En dit wat anicca is, is dit dukkha of sukha?

- Dukkha, Bhante.

-

En wat anicca, dukkha, van nature onderhewig is aan verandering, is dit

gepas om dit te beskou as: ‘Dit is myne. Ek is dit. Dit is my atta? ‘

- Nee, Bhante.

-

Daarom, bhikkhus, ongeag die rûpa, hetsy dit die verlede, die toekoms

of die hede is, intern of ekstern, grof of subtiel, minderwaardig of

verhewe, ver of naby, enige rûpa moet op hierdie manier yathā · bhūtaṃ

met behoorlike paññā gesien word: Dit is nie myne nie, ek is nie dit

nie, dit is nie my atta nie. ‘

Wat ook al vedanā, of dit nou

verby, in die toekoms of in die hede is, intern of ekstern, grof of

subtiel, minderwaardig of verhewe, ver of naby, elke vedanā is te sien

op hierdie manier yathā · bhūtaṃ met die regte paññā: ‘Dit is nie myne

nie Ek is dit nie, dit is nie my atta nie. ‘

Wat ook al saññā, of

dit nou die verlede, die toekoms of die hede is, intern of ekstern,

grof of subtiel, minderwaardig of verhewe, ver of naby, enige saññā is

op hierdie manier yathā · bhūtaṃ met behoorlike paññā te sien: ‘Dit is

nie myne nie, Ek is dit nie, dit is nie my atta nie. ‘

Wat ook al

die saṅkhāras is, of dit nou verby, in die toekoms of in die hede is,

intern of ekstern, grof of subtiel, minderwaardig of verhewe, ver of

naby, enige saṅkhāras kan gesien word op hierdie manier yathā · bhūtaṃ

met behoorlike paññā: ‘Dit is nie myne nie, Ek is dit nie, dit is nie my

atta nie. ‘

Wat ook al viññāṇa, hetsy in die verlede, in die

toekoms, of in die huidige, interne of eksterne, growwe of subtiele,

minderwaardige of verhewe, ver of naby, enige viññāṇa is te sien op

hierdie manier: Ek is dit nie, dit is nie my atta nie. ‘

gesien, is ‘n verligte edele dissipel teleurgesteld met Raba, ontevrede

met pyn, teleurgesteld met die dood, teleurgesteld met chakras en

teleurgesteld met Via. Teleurgesteld raak hy emosioneel. Deur depressie is hy verlig. Met bevryding isa: ‘bevry.’ Hy

verstaan: ‘Geboorte is verby, die Brahmaanlewe word geleef, wat gedoen

moet word, word gedoen, daar is niks anders vir hierdie bestaan nie.’

Dit is wat Bhagwar gesê het. Die groep van vyf monnike wat verheug was, was verheug oor sy woorde.

Toe hierdie openbaring gegee is, is die sitades van die groep van vyf monnike, sonder om vas te hou, van die dood bevry.

SN 22.59 (S iii 66)

Anattalakkhana Sutta

- Karakteristikë e jo-Vetë -

[anatt · lakkhaṇa]

Në këtë sutta shumë të famshme, Buda shpalos për herë të parë mësimet e tij mbi anatta.

Në një rast, Bhagavā po qëndronte në Bārāṇasi në Grove të Drerave në Isipatana. Atje, ai iu drejtua grupit prej pesë bhikkhus:

- Bhikkhus.

- Bhadante, u përgjigj bhikkhus. Bhagavā tha:

-

Rūpa, bhikkhus, është anatta. Dhe nëse kjo rūpa do të ishte atta,

bhikkhus, kjo rūpa nuk do të jepte veten për t’u çlodhur dhe mund të

[thuhej] për rūpa: ‘Le të jetë rūpa ime kështu, le të mos jetë rūpa ime

kështu.’ Por është për shkak se rūpa është anatta që rūpa jep hua për

t’u lehtësuar dhe se nuk mund të [thuhet] për rūpa: ‘Le të jetë r bepa

ime kështu, le të mos jetë rupa ime kështu.’

Vedanā, bhikkhus,

është anatta. Dhe nëse ky vedanā do të ishte atta, bhikkhus, ky vedanā

nuk do të jepte veten për t’u çlodhur dhe do të [mund të thuhej] për

vedan ‘:’ Le të jetë kështu vedanja ime, le të mos jetë kështu vedanja

ime. ‘ Por është për shkak se vedanā është anatta që vedanā jep veten

për t’u lehtësuar dhe se nuk mund të [thuhet] për vedanā: ‘Le të jetë

kështu vedanja ime, le të mos jetë kështu vedanja ime.’

Saññā,

bhikkhus, është anatta. Dhe nëse ky saññā do të ishte atta, bhikkhus, ky

saññā nuk do të jepte veten për t’u çlodhur dhe do të [mund të thuhej]

për saññā: ‘Le të jetë kështu sa my im, le të mos jetë kështu sa’. Por

është për shkak se saññā është anatta që jep veten për t’u lehtësuar dhe

se nuk mund të [thuhet] për saññā: ‘Le të jetë kështu saññā im, le të

mos jetë kështu sau im.’

Saṅkhāras, bhikkhus, janë anatta. Dhe

nëse këto sahara do të ishin atta, bhikkhus, këto sahara nuk do të

jepnin hua për t’u çlodhur dhe do të mund të [thuhej] për sahṅras: ‘Le

të jenë kështu saharat e mia, le të mos jenë sahajet e mia kështu.’ Por

është për shkak se saṅkṅras janë anatta që sahāras huazojnë veten e tyre

për t’u lehtësuar dhe se nuk mund të [thuhet] për sa :kāras: ‘Le të

jenë kështu sahahrat e mia, le të mos jenë saharat e mia kështu.’

Viññāṇa,

bhikkhus, është anatta. Dhe nëse kjo viññāṇa do të ishte atta,

bhikkhus, kjo viññāṇa nuk do të jepte veten për t’u lehtësuar dhe do të

[mund të thuhej] për viññāṇa: ‘Le të jetë kështu viça ime, le të mos

jetë kështu viça ime.’ Por është për shkak se viññāṇa është anatta që

viññāṇa jep veten për t’u lehtësuar dhe se nuk mund të [thuhet] për

viññāṇa: ‘Le të jetë kështu viça ime, le të mos jetë kështu viça ime.’

Çfarë mendoni për këtë, bhikkhus: a është Rūpa e përhershme apo anica?

i përkohshëm

- Anicca, Bhanthdhe

- Dhe ajo që është anicca, është dukkha apo sukha? {1}

- Dukkha, Bhante.

-

Dhe ajo që është anicca, dukkha, nga natyra që mund të ndryshojë, a

është e përshtatshme ta konsiderojmë si: ‘Kjo është e imja. Une jam ky

Kjo është atta ime? ‘

- Jo, Bhante.

- A është Vedanā i përhershëm apo anicca?

- Anicca, Bhante.

- Dhe ajo që është anicca, është dukkha apo sukha?

- Dukkha, Bhante.

-

Dhe ajo që është anicca, dukkha, nga natyra që mund të ndryshojë, a

është e përshtatshme ta konsiderojmë si: ‘Kjo është e imja. Une jam ky

Kjo është atta ime? ‘

- Jo, Bhante.

- A është Saññā i përhershëm apo anica?

- Anicca, Bhante.

- Dhe ajo që është anicca, është dukkha apo sukha?

- Dukkha, Bhante.

-

Dhe ajo që është anicca, dukkha, nga natyra që mund të ndryshojë, a

është e përshtatshme ta konsiderojmë si: ‘Kjo është e imja. Une jam ky

Kjo është atta ime? ‘

- Jo, Bhante.

- A janë Saṅkhāras të përhershme apo anica?

- Anicca, Bhante.

- Dhe ajo që është anicca, është dukkha apo sukha?

-

Dhe ajo që është anicca, dukkha, nga natyra që mund të ndryshojë, a

është e përshtatshme ta konsiderojmë si: ‘Kjo është e imja. Une jam ky

Kjo është atta ime? ‘

- Jo, Bhante.

- A është Viññāṇa e përhershme apo anica?

- Anicca, Bhante.

- Dhe ajo që është anicca, është dukkha apo sukha?

- Dukkha, Bhante.

-

Dhe ajo që është anicca, dukkha, nga natyra që mund të ndryshojë, a

është e përshtatshme ta konsiderojmë si: ‘Kjo është e imja. Une jam ky

Kjo është atta ime? ‘

- Jo, Bhante.

- Prandaj, bhikkhus, cilido

rūpa, qoftë i kaluar, i ardhshëm, apo i tanishëm, i brendshëm ose i

jashtëm, bruto ose delikat, inferior ose i ekzaltuar, larg apo afër, çdo

rūpa duhet të shihet yathā · bhūtaṃ me pa proper të duhur në këtë

mënyrë: ‘ Kjo nuk është e imja, unë nuk jam kjo, kjo nuk është e imja. ‘

Cilado

qoftë vedanā, qoftë e kaluara, e ardhmja, apo e tashmja, e brendshme

ose e jashtme, bruto ose delikate, inferiore ose e ekzaltuar, larg apo

afër, çdo vedanā duhet parë yathā · bhūtaṃ me pa proper të duhur në këtë

mënyrë: ‘Kjo nuk është e imja, Unë nuk jam kjo, kjo nuk është atta ime.

‘

Cilado qoftë sa be, qoftë e kaluara, e ardhmja, apo e tashmja,

e brendshme ose e jashtme, bruto ose delikate, inferiore ose e

ekzaltuar, larg apo afër, çdo saññā duhet parë yathā · bhūtaṃ me paññā

të duhur në këtë mënyrë: ‘Kjo nuk është e imja, Unë nuk jam kjo, kjo nuk

është atta ime. ‘

Cilido sahṅras, qofshin ato të kaluara, të

ardhme, apo të tashme, të brendshme ose të jashtme, bruto ose delikate,

inferiore ose të lartësuara, larg apo afër, çdo sahara duhet të shihet

yathā · bhūtaṃ me pa proper të duhur në këtë mënyrë: ‘Kjo nuk është e

imja, Unë nuk jam kjo, kjo nuk është atta ime. ‘

Cilado viññāṇa,

qoftë e kaluara, e ardhmja, apo e tashmja, e brendshme apo e jashtme,

bruto ose delikate, inferiore ose e ekzaltuar, larg apo afër, çdo

viññāṇa duhet parë yathā · bhūtaṃ me paññā të duhur në këtë mënyrë: ‘Kjo

nuk është e imja, Unë nuk jam kjo, kjo nuk është atta ime. ‘

në këtë mënyrë, një dishepull fisnik i ndriçuar zhgënjehet me Raba, i

pakënaqur me dhimbjen, i zhgënjyer me vdekjen, i zhgënjyer me chakrat

dhe i zhgënjyer me Via. I zhgënjyer, ai bëhet emocional. Përmes depresionit, ai lirohet. Me çlirimin, isa: ‘e çliruar’. Ai e kupton: ‘Lindja ka mbaruar, jeta Brahmin jetohet, bëhet ajo që duhet të bëhet, nuk ka asgjë tjetër për këtë ekzistencë.’

Kjo është ajo që tha Bhagwar. Grupi prej pesë murgjve që ishin të kënaqur ishin të kënaqur nga fjalët e tij.

Kur u dha kjo zbulesë, kështjellat e grupit prej pesë murgjish, pa u ngjitur, u çliruan nga vdekja.

SN 22.59 (S iii 66)

አናታላክቻና ሱታ

- የራስ-ማንነት ባሕርይ -

[አናታላካሃ]

በዚህ በጣም ታዋቂ ሱታ ውስጥ ቡዳ ለመጀመሪያ ጊዜ በአንታታ ላይ ትምህርቱን ገለፀ ፡፡

ባጋቫ በአንድ ወቅት በኢሲፓታና በሚገኘው የአጋዘን ግሮቭ ውስጥ ባራዛṇ ውስጥ ቆየ ፡፡ እዚያም ለአምስት የቢችሁስ ቡድን ንግግር አደረገ ፡፡

- ብሂክሁስ ፡፡

- ብሃዳንቴ ፣ ብሕክሹስ መለሰ። ብሃጋቫ እንዲህ አለ

-

ሩፓ ፣ ቢኪሁስ አናታ ነው ፡፡ እናም ይህ ሩፓ ቢታከስ ቢሆን ኖሮ ይህ ራፕ ለመረበሽ ራሱን አይሰጥም ነበር እናም

ስለ ሩፓ ‹ራፓዬ እንደዚህ ይሁን ፣ የእኔም ሩባ እንደዚህ አይሁን› ሊባል ይችላል ፡፡ ግን ራፓ እራሷን

ለማስታገስ የምትሰጥ ራታ አናታ ስለሆነች ነው ፣ እናም ስለ ሩፋ ‹ሩፓዬ እንደዚህ ይሁን ፣ የእኔም እንደዚህ

አይሁን› ሊባል ስለማይችል ነው ፡፡

ቬዳና ፣ ቢክሁሁስ አናታ ናት። እናም ይህ ቨዳአታ ቢሆን ኖሮ ፣

ቢኪክሁስ ፣ ይህ ቨዳን ለመረበሽ ራሱን አይሰጥም ነበር ፣ እናም ስለ ቬዳና ሊባል ይችላል-‹ቨዳና እንደዚህ ይሁን ፣

ቨዳና እንደዚህ አይሆንም› ግን ኢዳና አንታታ ስለሆነች ነው እናም ቨዳን ለመረበሽ የሚሰጥ ፣ እናም ቨዳና ሊባል

ስለማይችል ‹የእኔ ቨዳና እንደዚህ ይሁን ፣ ቨዳኔ እንደዚህ አይሆንም›

ሳአህ ፣ ቢክህሁስ አናታ ነው።

እናም ይህ ሳታ ቢታኪስ ቢሆን ኖሮ ይህ ሳሃ ለመረበሽ ራሱን አይሰጥም ነበር እናም ስለ ሳሃ ‹ሳሃዬ እንደዚህ ይሁን

፣ ሳሃዬ እንደዚህ አይሁን› ሊባል ይችላል ፡፡ ግን ሳዓ ለጭንቀት ራሱን አሳልፎ የሰጠ አንታ ስለሆነ ነው እናም

ስለ ሳሃ ሊባል ስለማይችል ‹የእኔ ሳሃ እንደዚህ ይሁን ፣ የእኔም እንደዚህ አይሁን› ፡፡

ሳህካራስ ፣

ቢክህሁስ አናታ ናቸው። እናም እነዚህ ሳህካራዎች ቢታክሁስ ቢሆኑ ኖሮ እነዚህ ሳህካሮች ለችግር ራሳቸውን አይሰጡም

ነበር እናም ስለ ሳህካራስ ‹የእኔ ሳካህራህ እንደዚህ ይሁን ፣ የእኔ ሳህካራራ እንደዚህ አይሁን› ሊባል ይችላል

፡፡ ግን ሳህካራ አንታታ በመሆናቸው ሳሃካራስ ራሳቸውን ለማስቻል ያበደሩ ስለሆኑ እና ስለ ሳህካራስ ‹የእኔ

ሳካህራህ እንደዚህ ይሁን ፣ የእኔ ሳህካራራ እንደዚህ አይሁን› ሊባል ስለማይችል ነው ፡፡

ቪያና ፣

ቢኪክሁስ አናታ ነው። እናም ይህ ቪኒያ እና ቢቺክስ ቢሆን ኖሮ ይህ ቪዛ ለመረበሽ ራሱን አይሰጥም ነበር እናም ስለ

ቪያና ‹ቪያናዬ እንደዚህ ይሁን ፣ ቪያናዬ እንደዚህ አይሁን› ሊባል ይችላል ፡፡ ግን viññā ana anatta

ስለሆነ ነው ቪያና ለመከራ የሚሰጥ ፣ እና ስለ ቪያና ሊባል ስለማይችል ‹ቪያናዬ እንደዚህ ይሁን ፣ ቪዬና እንደዚህ

አይሆንም›

ቢቺሁስ ስለዚህ ምን ይመስላችኋል-ሩፓ ቋሚ ወይም አኒካካ ነው?

ጊዜያዊ

- አኒካካ, ባንትህደ

- እና አኒካካ የሆነው ዱካ ወይም ሱካ ነው? {1}

- ዱክሃ ፣ ባህንት ፡፡

- እናም አኒካካ ፣ ዱካ ፣ በተፈጥሮው ሊለወጥ የሚችል ፣ እንደ ‹ይህ የእኔ ነው› ብሎ መቁጠር ተገቢ ነው ፡፡ እኔ ነኝ ፡፡ ይህ የእኔ አተታ ነው? ‘

- የለም ፣ ብሃንት ፡፡

- ቬዳና ዘላቂ ወይም አኒካካ ነው?

- አኒካካ ፣ ባንተ ፡፡

- እና አኒካካ የሆነው ዱካካ ነው ወይስ sukha?

- ዱክሃ ፣ ባህንት ፡፡

- እናም አኒካካ ፣ ዱካካ በተፈጥሮው ሊለወጥ የሚችል ፣ እንደ ‹ይህ የእኔ ነው› ብሎ መቁጠር ተገቢ ነው ፡፡ እኔ ነኝ ፡፡ ይህ የእኔ አተታ ነው? ‘

- የለም ፣ ብሃንት ፡፡

- ሳአሳ ቋሚ ነው ወይም አኒካካ ነው?

- አኒካካ ፣ ባንተ ፡፡

- እና አኒካካ የሆነው ዱካካ ነው ወይስ sukha?

- ዱክቻ ፣ ባህንት ፡፡

- እና አኒካካ ፣ ዱካ ፣ በተፈጥሮው ሊለወጥ የሚችል ፣ እንደ ‹ይህ የእኔ ነው› ብሎ መቁጠር ተገቢ ነው ፡፡ እኔ ነኝ ፡፡ ይህ የእኔ አተታ ነው? ‘

- የለም ፣ ብሃንት ፡፡

- ሳህካራስ ቋሚ ነው ወይስ አኒካካ?

- አኒካካ ፣ ባንተ ፡፡

- እና አኒካካ የሆነው ዱካ ወይም ሱካ ነው?

- እናም አኒካካ ፣ ዱካካ በተፈጥሮው ሊለወጥ የሚችል ፣ እንደ ‹ይህ የእኔ ነው› ብሎ መቁጠር ተገቢ ነው ፡፡ እኔ ነኝ ፡፡ ይህ የእኔ አተታ ነው? ‘

- የለም ፣ ብሃንት ፡፡

- ቪያና ዘላቂ ወይም አኒካካ ነው?

- አኒካካ ፣ ባንተ ፡፡

- እና አኒካካ የሆነው ዱካካ ነው ወይስ sukha?

- ዱክሃ ፣ ባህንት ፡፡

- እና አኒካካ ፣ ዱካ ፣ በተፈጥሮው ሊለወጥ የሚችል ፣ እንደ ‹ይህ የእኔ ነው› ብሎ መቁጠር ተገቢ ነው ፡፡ እኔ ነኝ ፡፡ ይህ የእኔ አተታ ነው? ‘

- የለም ፣ ብሃንት ፡፡

-

ስለዚህ ፣ ቢኪክሁስ ፣ ምንም ይሁን ምንም ሩፓ ፣ ያለፈ ፣ የወደፊቱ ወይም የአሁኑ ፣ ውስጣዊም ሆነ ውጫዊ ፣

ከባድ ወይም ረቂቅ ፣ የበታች ወይም ከፍ ያለ ፣ ሩቅም ይሁን ቅርብ ፣ ማንኛውም ሩፓ በዚህ መንገድ በተገቢው ፓሻ

አማካኝነት ያትባህታይ መታየት አለበት: - ይህ የእኔ አይደለም ፣ እኔ ይህ አይደለሁም ፣ ይህ የእኔ የእኔ ፍላጎት

አይደለም። ’

ምንም ይሁን ፣ ያለፈ ፣ የወደፊቱ ወይም የአሁኑ ፣ ውስጣዊም ሆነ ውጫዊ ፣ ከባድ ወይም

ረቂቅ ፣ የበታች ወይም ከፍ ያለ ፣ ቅርብም ይሁን ከፍ ያለ ማንኛውም ቨዳና በዚህ መንገድ በተገቢው ፓሻ

አማካኝነት ያትባህታይ መታየት አለበት-‹ይህ የእኔ አይደለም ፣ እኔ ይህ አይደለሁም ፣ ይህ የእኔ ፍላጎት አይደለም

፡፡

ያለፈው ፣ የወደፊቱ ወይም የአሁኑ ፣ ውስጣዊም ሆነ ውጫዊ ፣ ከባድ ወይም ረቂቅ ፣ የበታች ወይም

ከፍ ያለ ፣ ሩቅ ይሁን ቅርብ የሆነ ማንኛውም ሳዓ በዚህ መንገድ በተገቢው ፓሻ አማካኝነት ያትባህታይ መታየት

አለበት-‹ይህ የእኔ አይደለም ፣ እኔ ይህ አይደለሁም ፣ ይህ የእኔ ፍላጎት አይደለም ፡፡

የትኛውም

ሳካህራስ ያለፈ ፣ የወደፊቱ ወይም የአሁኑ ፣ ውስጣዊም ሆነ ውጫዊ ፣ ከባድ ወይም ረቂቅ ፣ የበታች ወይም ከፍ ያለ

፣ ቅርብም ይሁን ቅርብ ፣ ማንኛውም ሳህካራ በዚህ መንገድ በተገቢው ፓሻ አማካኝነት ያትባህታይ መታየት

አለበት-‹ይህ የእኔ አይደለም ፣ እኔ ይህ አይደለሁም ፣ ይህ የእኔ ፍላጎት አይደለም ፡፡

ቪያና ያለፈው

፣ የወደፊቱ ወይም የአሁኑ ፣ ውስጣዊም ሆነ ውጫዊ ፣ ከባድ ወይም ረቂቅ ፣ የበታች ወይም ከፍ ያለ ፣ ቅርብም

ይሁን ቅርብ ፣ ማንኛውም ቪያና በዚህ መንገድ በተገቢው ፓሻ አማካኝነት ያትባህታይ መታየት አለበት ‹ይህ የእኔ

አይደለም ፣ እኔ ይህ አይደለሁም ፣ ይህ የእኔ ፍላጎት አይደለም ፡፡

ብሃገር የተናገረው ይህ ነው ፡፡ የተደሰቱ አምስት መነኮሳት ቡድን በቃላቱ ተደስተዋል ፡፡

ይህ መገለጥ ሲሰጥ የአምስት መነኮሳት ቡድን ሰፈሮች ሳይጣበቁ ከሞት ተለቀዋል ፡፡

SN 22.59 (S iii 66)

Anattalakkhana Sutta

- صفة اللاذات -

[anattā lakkhaṇa]

في هذه السوتا الشهيرة جدًا ، يشرح بوذا لأول مرة تعاليمه عن الأناتا.

في إحدى المناسبات ، كان البهاغافا يقيمون في باراسي في دير غروف في إسيباتانا. هناك خاطب جماعة الخمسة من البيك خوس:

- بخس.

- Bhadante ، أجاب bhikkhus. قال البهاغافا:

-

Rūpa ، bhikkhus ، هو عناتا. وإذا كانت هذه rūpa هي atta ، bhikkhus ، فإن

هذا rūpa لن يفسح المجال للازعاج ، ويمكن [أن يقال] عن rūpa: “فلتكن ربا

على هذا النحو ، فليكن rūpa هكذا.” ولكن لأن rūpa هو anatta ، فإن rūpa

يفسح المجال للقلق ، ولا يمكن [أن يقال] عن rūpa: “دع ربا يكون هكذا ، دع

ربا لا يكون هكذا”.

Vedanā ، bhikkhus ، هو عناتا. وإذا كانت هذه

الفدانا عطا ، بخس ، فإن هذه الفدانا لن تكون قابلة للتخفيف ، ويمكن [أن

يقال] عن فيدانا: “ليكن فدانا هكذا ، فلا يكون فدانا هكذا”. ولكن لأن

فيدانا عناتة ، فإن فيدانا يفسح المجال للمرض ، ولا يمكن [أن يقال] عن

فيدانا: “فليكن فدانا هكذا ، فلا تكون فدانا هكذا”.

سانيا ،

bhikkhus ، هي عناتا. وإذا كانت هذه السانا هي آتا ، بهيكه ، فلن تكون هذه

السانا قابلة للازعاج ، ويمكن [أن يُقال] عن سانا: “دعنا سنانا هكذا ، دعني

لا تكون هكذا”. ولكن لأن sañā هو anatta ، فإن sañā يفسح المجال للقلق ،

ولا يمكن [أن يقال] عن sañā: “دع السانا الخاصة بي تكون هكذا ، دعها لا

تكون هكذا”.

Saṅkhāras ، bhikkhus ، هم عناتا. ولو كانت هذه الصحارى

عطا ، بخس ، فهذه الصحارى لن تكون قابلة للازعاج ، ويمكن أن يقال عن

الصحارى: “لتكن صحارى على هذا النحو ، فلا تصح صحارى هكذا”. لكن لأن

السحارات هي عنات هي التي تستدعي السخارات نفسها للتخفيف ، ولا يمكن [أن

يقال] عن الصحارى: “فلتكن صحارتي هكذا ، فلا تصح صحارتي هكذا”.

Viñāa

، bhikkhus ، هو عناتا. وإذا كانت هذه viñāa هي atta ، bhikkhus ، فلن

تكون هذه viñāa قابلة للازعاج ، ويمكن [أن يقال] عن viñāa: “دع فينيانا

تكون هكذا ، دع فينيانا لا تكون هكذا”. ولكن نظرًا لأن viñāṇa هو anatta ،

فإن viñāa يفسح المجال للتخفيف ، ولا يمكن [أن يُقال] عن viññāa: “دع viñāa

يكون هكذا ، دع فطري لا يكون هكذا”.

ما رأيك في هذا ، bhikkhus: هل Rūpa دائم أم أنيكا؟

مؤقت

- Anicca، Bhanthdhe

- وما هي الأنيكا ، هل هي دخان أم سخة؟ {1}

- Dukkha، Bhante.

- وما هو anicca ، dukkha ، بطبيعته عرضة للتغيير ، فهل من المناسب اعتباره على أنه: انا هذا. هذا هو عطا الخاص بي؟

- لا ، بهانت.

- هل فيدانا دائم أم أنيكا؟

- أنيكا ، بهانت.

- وما أنيكا هل هي دخا أم سخة؟

- Dukkha، Bhante.

- وما هو anicca ، dukkha ، بطبيعته عرضة للتغيير ، فهل من المناسب اعتباره على أنه: ‘هذا هو لي. انا هذا. هذا هو عطا الخاص بي؟

- لا ، بهانت.

- هل سانيا دائمة أم أنيكا؟

- أنيكا ، بهانت.

- وما أنيكا هل هي دخا أم سخنة؟

- Dukkha، Bhante.

- وما هو anicca ، dukkha ، بطبيعته عرضة للتغيير ، فهل من المناسب اعتباره على أنه: ‘هذا هو لي. انا هذا. هذا هو عطا الخاص بي؟

- لا ، بهانت.

- هل الساخرات دائمة أم أنيكا؟

- أنيكا ، بهانت.

- وما أنيكا هل هي دخا أم سخة؟

- وما هو anicca ، dukkha ، بطبيعته عرضة للتغيير ، فهل من المناسب اعتباره على أنه: ‘هذا هو لي. انا هذا. هذا هو عطا الخاص بي؟

- لا ، بهانت.

- هل Viñāa دائم أم أنيكا؟

- أنيكا ، بهانت.

- وما أنيكا هل هي دخا أم سخة؟

- Dukkha، Bhante.

- وما هو anicca ، dukkha ، بطبيعته عرضة للتغيير ، فهل من المناسب اعتباره على أنه: ‘هذا هو لي. انا هذا. هذا هو عطا الخاص بي؟

- لا ، بهانت.

-

لذلك ، bhikkhus ، بغض النظر عن rūpa ، سواء كان ذلك في الماضي أو

المستقبل أو الحاضر ، داخليًا أو خارجيًا ، فظيعًا أو دقيقًا ، أدنى أو

مرتفعًا ، بعيدًا أو قريبًا ، أي rūpa يجب رؤيته yathā · bhūtaṃ مع البانيا

المناسبة بهذه الطريقة: هذا ليس لي ، أنا لست هذا ، هذا ليس عطا.

مهما

كانت الفدانا ، سواء كانت في الماضي أو المستقبل أو الحاضر ، داخلية أو

خارجية ، فاضحة أو خفية ، أدنى أو مرتفعة ، بعيدة أو قريبة ، يجب رؤية أي

فيدانا مع البانيا المناسبة بهذه الطريقة: “ هذا ليس لي ، أنا لست هذا ،

هذا ليس عطا الخاص بي.

مهما كانت السانيا ، سواء كانت في الماضي أو

المستقبل أو الحاضر ، داخلية أو خارجية ، فاضحة أو خفية ، أدنى أو ممجدة ،

بعيدة أو قريبة ، فإن أي سانا يمكن رؤيتها مع البانيا المناسبة بهذه

الطريقة: ‘هذا ليس لي ، أنا لست هذا ، هذا ليس عطا الخاص بي.

مهما

كانت السحارات ، سواء كانت سابقة أو مستقبلية أو حاضرة ، داخلية أو خارجية ،

فاضحة أو خفية ، أدنى أو عالية ، بعيدة أو قريبة ، يجب رؤية أي ساحرات مع

البانيا الصحيحة بهذه الطريقة: “ هذا ليس لي ، أنا لست هذا ، هذا ليس عطا

الخاص بي.

أيًا كان vññāa ، سواء كان في الماضي أو المستقبل أو

الحاضر ، داخليًا أو خارجيًا ، فاضحًا أو خفيًا ، أدنى أو مرتفعًا ، بعيدًا

أو قريبًا ، يجب رؤية أي vññāa مع paññā بطريقة صحيحة بهذه الطريقة: “

هذا ليس لي ، أنا لست هذا ، هذا ليس عطا الخاص بي.

الطريقة ، يشعر تلميذ نبيل مستنير بخيبة أمل من رابا ، غير راضٍ عن الألم ،

محبط من الموت ، محبط من الشاكرات ، وخيب أمل من فيا. بخيبة أمل ، يصبح عاطفيًا. من خلال الاكتئاب ، يشعر بالارتياح. مع التحرير عيسى: “حرر”. إنه يفهم: “الولادة انتهت ، وعشت حياة براهمين ، وما يجب القيام به هو القيام به ، ولا يوجد شيء آخر لهذا الوجود”.

هذا ما قاله بهاجوار. وقد سُرَّت كلماته المجموعة المكونة من خمسة رهبان.

عندما أُعطي هذا الوحي ، تحررت قلاع المجموعة المكونة من خمسة رهبان ، دون أن تلتصق ، من الموت.

SN 22.59 (S iii 66)

Anattalakkhana Sutta

- Ոչ-ի բնութագիրը -

[anattā · lakkhaṇa]

Այս շատ հայտնի սուտայում Բուդդան առաջին անգամ բացատրում է իր ուսմունքը անատտայի մասին:

Մի առիթով, Bhagavā- ն բնակվում էր Bārāṇasi- ում, Isipatana- ի Deer Grove- ում: Այնտեղ նա դիմեց հինգ բիխխուսների խմբին.

- Բհիկխուս:

- Բադանտե, - պատասխանեց բհիկխուսը: Բհագավն ասաց.

-

Rūpa, bhikkhus, անատտա է: Եվ եթե այս ռիփան լիներ ատհա, բիխխուս, ապա այս

ռափան իրեն թույլ չէր տա խանգարել, և կարող էր [ասել] ռապայի մասին. «Թող

իմ ռիփան այսպիսին լինի, թող իմ ռյուփան այդպես չլինի»: Բայց այն պատճառով,

որ rūpa- ն անատտա է, որը rpa- ն իրեն տրամադրում է հանգստանալու, և որ

rupa- ի մասին չի կարելի [ասել]. «Թող իմ rūpa- ն այսպիսին լինի, թող իմ

rūpa- ն այսպիսին չլինի»:

Vedanā, bhikkhus, անատտա է: Եվ եթե այս

vedanā- ը atta, bhikkhus լիներ, ապա այս vedanā- ն իրեն թույլ չէր տա

խանգարել, և vedanā- ի մասին [կարելի էր ասել]. «Թող իմ vedan- ը այսպես

լինի, թող իմ vedanā- ն այդպես չլինի»: Բայց այն պատճառով, որ vedanā- ն

անատտա է, որը vedanā- ն իրեն տրամադրում է հանգստանալու, և որ չի կարող

[ասել] vedanā- ի մասին. «Թող իմ վեդը լինի այսպես, թող իմ վեդը չլինի

այդպիսին»:

Saññā, bhikkhus, անատտա է: Եվ եթե այս saññā- ն Atta,

bhikkhus լիներ, ապա այս saññā- ը չէր տա իրեն հանգստանալու, և կարելի էր

[ասել] saññā- ի մասին. «Թող իմ saññā- ն այսպես լինի, թող իմ saññā- ն

այդպես չլինի»: Բայց այն պատճառով, որ saññā- ն անատտա է, որն իրեն

տրամադրում է հանգստանալու, և որ չի կարող [ասել] saññā- ի մասին.

Saṅkhāras,

bhikkhus, անատտա են: Եվ եթե այս սախիրաները լինեին ատհա, բիկխուս, ապա

այս սախարաները չէին տա իրենց տհաճություն, և կարելի էր [ասել] սախիրաների

մասին. «Թող իմ սախարաներն այսպիսին լինեն, թող իմ սախարանաներն այսպիսին

չլինեն»: Բայց սա այն պատճառով է, որ սախիրաներն անատտան են, որ սախիրան

իրեն թույլ է տալիս հանգստանալ, և որ չի կարող [ասվել] սախիրայի մասին.

«Թող իմ սախարաններն այսպիսին լինեն, թող իմ սախարանաներն այսպիսին

չլինեն»:

Viññāṇa, bhikkhus, անատտա է: Եվ եթե այս viññāṇa- ն atta,

bhikkhus լիներ, ապա այս viññāṇa- ն իրեն չէր տա հանգստանալու, և կարելի

էր [ասել] viññāṇa- ի մասին. «Թող իմ viññāṇa- ն այսպես լինի, թող viññāṇa-

ն այդպես չլինի»: Բայց այն պատճառով, որ viññāṇa- ն անատտա է, viññāṇa- ն

իրեն տրամադրում է հանգստանալու, և որ չի կարելի [ասել] viññāṇa- ի մասին.

«Թող իմ viññāṇa- ն այսպես լինի, թող viññāṇa- ն այդպես չլինի»:

Ի՞նչ եք մտածում այս մասին, բհիկխուս. Rūpa- ն մշտական է, թե անիկկա:

ժամանակավոր

- Անիկկա, Բանթդհե

- Եվ այն, ինչը անիկկա է, դա դուխխա՞ է, թե՞ սուխա: {1}

- Դուկխա, Բհանտե:

- Եվ այն, ինչը անիկկա է, դուխխա, ըստ էության փոփոխման ենթակա է, պատշաճ է՞ համարել այն ՝ «Սա իմն է: Ես սա եմ Սա իմ ատտա՞ն է »:

- Ոչ, Բհանտե:

- Vedanā- ն մշտակա՞ն է, թե՞ անիկկա:

- Անիկկա, Բհանտե:

- Եվ այն, ինչը անիկկա է, դո՞ւխկա է, թե՞ սուխա:

- Դուկխա, Բհանտե:

- Եվ այն, ինչը անիկկա է, դուխխա, ըստ էության փոփոխման ենթակա է, պատշաճ է՞ համարել այն ՝ «Սա իմն է: Ես սա եմ Սա իմ ատտա՞ն է:

- Ոչ, Բհանտե:

- Saññā- ը մշտակա՞ն է, թե՞ անիկկա:

- Անիկկա, Բհանտե:

- Եվ այն, ինչը անիկկա է, դա դուխխա՞ է, թե՞ սուխա:

- Դուկխա, Բհանտե:

- Եվ այն, ինչը անիկկա է, դուխխա, ըստ էության փոփոխման ենթակա է, պատշաճ է՞ համարել այն ՝ «Սա իմն է: Ես սա եմ Սա իմ ատտա՞ն է »:

- Ոչ, Բհանտե:

- Saṅkhāras- ը մշտակա՞ն է, թե՞ անիկկա:

- Անիկկա, Բհանտե:

- Եվ այն, ինչը անիկկա է, դո՞ւխկա է, թե՞ սուխա:

-

Եվ այն, ինչը անիկկա է, դուխխա, ըստ էության փոփոխման ենթակա է, պատշաճ է

այն համարել այսպես. «Սա իմն է: Ես սա եմ Սա իմ ատտա՞ն է »:

- Ոչ, Բհանտե:

- Viññāṇa- ն մշտակա՞ն է, թե՞ անիկկա:

- Անիկկա, Բհանտե:

- Եվ այն, ինչը անիկկա է, դա դուխխա՞ է, թե՞ սուխա:

- Դուկխա, Բհանտե:

- Եվ այն, ինչը անիկկա է, դուխխա, ըստ էության փոփոխման ենթակա է, պատշա՞ր է այն համարել որպես. «Սա իմն է: Ես սա եմ Սա իմ ատտա՞ն է:

- Ոչ, Բհանտե:

-

Հետևաբար, բհիկխուսը, անկախ նրանից, լինի դա անցյալ, ապագա, թե ներկա,

ներքին կամ արտաքին, կոպիտ կամ նուրբ, ստորադաս կամ վեհացված, հեռու կամ

մոտ, ցանկացած ռեպպա պետք է տեսնի յաթբահհաթա ՝ համապատասխան պատշաճ կերպով

այս եղանակով. Սա իմը չէ, ես սա չեմ, սա իմ ատան չէ »:

Ինչ էլ որ

լինի, լինի դա անցյալ, ապագա, թե ներկա, ներքին կամ արտաքին, կոպիտ կամ

նուրբ, ստորադաս կամ վեհացված, հեռու կամ մոտ, ցանկացած vedan to պետք է

տեսվի yathā · bhūtaū ՝ համապատասխան պատշաճ կերպով այս եղանակով. «Սա իմը

չէ, Ես սա չեմ, սա իմ ատան չէ »:

Ինչ էլ որ լինի, լինի դա անցյալ,

ապագա, թե ներկա, ներքին կամ արտաքին, կոպիտ կամ նուրբ, ստորադաս կամ

վեհացվող, հեռու կամ մոտ, ցանկացած Saññā պետք է տեսնվի yathā · bhūtaṃ ՝

համապատասխան պատշաճ կերպով այս եղանակով. «Սա իմը չէ, Ես սա չեմ, սա իմ

ատան չէ »:

Անկախ որևէ սախարայից, լինեն դրանք անցյալ, ապագա կամ

ներկա, ներքին կամ արտաքին, կոպիտ կամ նուրբ, ստորադաս կամ վեհացված, հեռու

կամ մոտ, ցանկացած սախարա պետք է տեսնվի yathā · bhūtaṃ ՝ համապատասխան

կերպով ՝ այսպես. «Սա իմը չէ, Ես սա չեմ, սա իմ ատան չէ »:

Անկախ

որևէ վիշա, լինի դա անցյալ, ապագա, թե ներկա, ներքին կամ արտաքին, կոպիտ

կամ նուրբ, ստորադաս կամ վեհացվող, հեռու կամ մոտ, ցանկացած viññāṇa պետք է

տեսնվի yathā · bhūtaṃ ՝ համապատասխան կերպով ՝ այս եղանակով. «Սա իմը չէ,

Ես սա չեմ, սա իմ ատան չէ »:

տեսքով լուսավորված ազնվական աշակերտը հիասթափված է Ռաբայից, դժգոհ է

ցավից, հիասթափվում է մահից, հիասթափվում է չակրաներից և հիասթափվում է

Վիայից: Հիասթափվելով ՝ նա հուզվում է: Դեպրեսիայի միջոցով նա թեթեւանում է: Ազատագրմամբ, isa. «Ազատագրված»: Նա հասկանում է. «Birthնունդն ավարտվեց, Բրահմանի կյանքն ապրեց, արվեց այն, ինչ պետք է արվի, այլ բան չկա այս գոյության համար»:

Ահա թե ինչ ասաց Բագվարը: Հինգ վանականներից բաղկացած խումբը հիացած էր նրա խոսքերով:

Երբ այս հայտնությունը տրվեց, հինգ վանականների խմբի միջնաբերդերը, առանց կպչելու, ազատվեցին մահից:

SN 22.59 (S iii 66)

Anattalakkhana Sutta

- Heç-özünəməxsus xüsusiyyət -

[anattā · lakkhaṇa]

Buda çox məşhur sutta, Buddha ilk dəfə anatta haqqında öyrətdiyini izah edir.

Bir dəfə Bhagavā, Isipatana’daki Geyik Meşəsindəki Bārāṇasi’də qalırdı. Orada beş hicquh qrupuna müraciət etdi:

- Bhikkhus.

- Bhadante, bhikkhus cavab verdi. Bhagava dedi:

-

Rūpa, bhikkhus, anattadır. Və əgər bu rpa atta olsaydı, bhikkhus, bu

rpa özünü rahatlaşdırmayacaqdı və rpa haqqında belə deyilə bilər: ‘Rəhəm

belə olsun, rəfam belə olmasın’. Ancaq rpa anatta olduğuna görə rpa

özünü rahatlaşdırmağa borcludur və rpa haqqında belə deyilə bilməz:

‘Rapam belə olsun, rpaım belə olmasın.’

Vedanā, bhikkhus,

anattadır. Və bu vedana atta olsaydı, bhikkhus, bu vedana özünü azaltmaq

üçün borc verməzdi və vedanaya belə deyilə bilər: ‘Mənim vedanam belə

olsun, mənim vedanam belə olmasın’. Lakin vedananın anatta olduğu üçün

vedananın özünü rahatlaşdırmağa borc verdiyi və vedana ilə [deyilə

bilmədiyi üçün: ‘Mənim vedanam belə olsun, mənim vedanam belə olmasın.’

Saññā,

bhikkhus, anatta. Və əgər bu bənzər atta, bhikkhus olsaydı, bu bənzər

özünü azaltmaq üçün borc verməzdi və sanqa belə deyilə bilər: ‘Qoy

sağlığım belə olsun, qoy mənim belə olmasın’. Fəqət saññā ananasadır ki,

saññā özünü rahatlaşdırmağa borc verir və saññā deyilə bilməz: ‘Mənim

sañam belə olsun, mənim sañam belə olmasın.’

Saṅkhāras, bhikkhus,

anatta. Və əgər bu sahharalar atta, bhikkhus olsaydı, bu saxaralar

özlərini rahatlaşdırmaq üçün borc verməzdilər və saxaralar haqqında

[deyilə bilər]: ‘Mənim saxaralarım belə olsun, mənim saaharalarım belə

olmasın’. Ancaq səharələrin anatta olduqları üçün sahharasların özlərini

rahatlaşdırmağa borc verdikləri və saxaralar haqqında deyilə bilmədiyi

üçün: ‘Qoy mənim saxaralarım belə olsun, mənim səhralarım belə olmasın’.

Viññāṇa,

bhikkhus, anattadır. Və əgər bu vínñāṇa atta, bhikkhus olsaydı, bu

vínñāṇa özünü azaltmaq üçün borc verməzdi və viññāṇa’dan [deyilə bilər]:

‘Qoy mənim vínñāṇa belə olsun, mənim vínñāṇa belə olmasın’. Lakin

viññāṇa anatta olduğundan, viññāṇa özünü rahatlaşdırmağa borc verir və

viññāṇa haqqında [deyilə] bilməz: ‘Qoy mənim viññāṇa belə olsun, mənim

viññāṇa belə olmasın.’

Bu barədə nə düşünürsən, bhikkhus: Rūpa qalıcıdır, yoxsa anicca?

müvəqqəti

- Anicca, Bhanthdhe

- Və anikca olan dukha, yoxsa suha? {1}

- Dukkha, Bhante.

-

Və təbiətə görə dəyişməyə məruz qalan anikka olan dukxa, bunu belə

qiymətləndirmək düzgündür: ‘Bu mənimdir. Mən bu. Bu mənim atta? ”

- Xeyr, Bhante.

- Vedanā qalıcıdır, yoxsa anicca?

- Anicca, Bhante.

- Və anikca olan, dukxa, yoxsa suha?

- Dukkha, Bhante.

-

Və təbiətə görə dəyişməyə məruz qalan anikka olan dukxa, bunu belə

qiymətləndirmək düzgündür: ‘Bu mənimdir. Mən bu. Bu mənim atta? ”

- Xeyr, Bhante.

- Saññā qalıcıdır, yoxsa anicca?

- Anicca, Bhante.

- Və anikca olan, dukxa, yoxsa suha?

- Dukkha, Bhante.

- Və təbiətcə dəyişdirilə bilən anikca olan dukxa, bunu belə qiymətləndirmək düzgündür: ‘Bu mənimdir. Mən bu. Bu mənim atta? ”

- Xeyr, Bhante.

- Saṅkhāras qalıcıdır, yoxsa anicca?

- Anicca, Bhante.

- Və anikca olan, dukxa, yoxsa suha?

-

Və təbiətə görə dəyişməyə məruz qalan anikka olan dukxa, bunu belə

qiymətləndirmək düzgündür: ‘Bu mənimdir. Mən bu. Bu mənim atta? ”

- Xeyr, Bhante.

- Viññāṇa qalıcıdır, yoxsa anicca?

- Anicca, Bhante.

- Və anikca olan, dukxa, yoxsa suha?

- Dukkha, Bhante.

-

Və təbiətə görə dəyişməyə məruz qalan anikka olan dukxa, bunu belə

qiymətləndirmək düzgündür: ‘Bu mənimdir. Mən bu. Bu mənim atta? ”

- Xeyr, Bhante.

-

Buna görə də, bhikkhuslar, keçmiş, gələcək və ya indiki, daxili və ya

xarici, qaba və ya incə, aşağı və ya uca, uzaq və ya yaxın olan hər

hansı bir rupa, yathābhūta proper’ı müvafiq bir pankon ilə bu şəkildə

görmək lazımdır: ‘ Bu mənim deyil, bu deyiləm, bu mənim atta deyil. ‘

Keçmiş,

gələcək və ya indiki, daxili və ya xarici, kobud və ya incə, aşağı və

ya uca, uzaq və ya yaxın nə olursa olsun, hər hansı bir vedana bu

şəkildə müvafiq pankon ilə yathābhūtaṃ görüləcəkdir: ‘Bu mənim deyil,

Mən bu deyiləm, bu mənim atta deyil. ‘

Keçmiş, gələcək və ya

indiki, daxili və xarici, kobud və ya incə, aşağı və ya uca, uzaq və ya

yaxın nə olursa olsun, hər hansı bir bənzər bir şəkildə bu şəkildə uyğun

bir pankon ilə yathābhūtaṃ görüləcəkdir: ‘Bu mənim deyil, Mən bu

deyiləm, bu mənim atta deyil. ‘

Keçmiş, gələcək və ya indiki,

daxili və xarici, kobud və ya incə, aşağı və ya uca, uzaq və ya yaxın nə

olursa olsun, hər hansı bir saṅkhāras yathābhūtaṃ ilə uyğun bir şəkildə

görünməlidir: ‘Bu mənim deyil, Mən bu deyiləm, bu mənim atta deyil. ‘

Keçmiş,

gələcək və ya indiki, daxili və xarici, kobud və ya incə, aşağı və ya

uca, uzaq və ya yaxın nə olursa olsun, hər hansı bir vínñāṇa

yathābhūtaṃ’ı uyğun bir şəkildə bu şəkildə görmək lazımdır: ‘Bu mənim

deyil, Mən bu deyiləm, bu mənim atta deyil. ‘

şəkildə görünən aydın bir nəcib şagird Rabadan məyus olur, ağrıdan

narazıdır, ölümdən məyus, çakralardan məyus və Via ilə məyusdur. Məyus olduqdan sonra o, emosional olur. Depressiya ilə rahatlanır. Qurtuluşla, isa: ‘azad edildi.’ Anlayır: ‘Doğum bitdi, Brahmin həyatı yaşandı, edilməsi lazım olanlar edildi, bu varlıq üçün başqa bir şey yoxdur.’

Bhagwar dedi. Sevinən beş rahibdən ibarət qrup onun sözlərindən məmnun qaldı.

Bu vəhy verildikdə, beş keşiş qrupunun qalaları, yapışmadan ölümdən azad edildi.

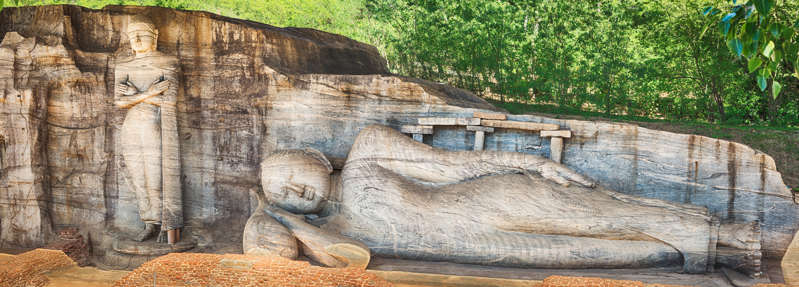

Gal Vihara, Sri Lanka

© GoodOlga/Getty Images

The UNESCO World Heritage Site, located in the ancient city of

Polonnaruwa in North Central Province of Sri Lanka, is considered as one

of the most important examples of ancient Sinhalese art. Constructed in

the 12th century, the Gal Vihara consists of granite sculptures of a

seated, standing and reclining Buddha.

Beautiful Buddha statues around the world

Apart from being the instruments of deep spiritual beliefs,

Buddha statues around the world are admired for their architectural

greatness. From rock reliefs to brightly painted sculptures, take a look

at some of these awe-inspiring intricate structures.

Reclining Buddha of Wat Pho, Thailand

© f9photos/Getty Images

One of the oldest temples in the country, situated in the capital city

of Bangkok, houses the largest reclining gold-plated Buddha built in

1848. The statue is 150 feet (46 meters) long and 49 feet (15 meters)

high and its eyes and feet are decorated with engraved mother of pearl.

Around 108 characteristics of the true Buddha are displayed on the soles

of the statue.

Leshan Giant Buddha, China

© Sipa Asia/Shutterstock

At 233 feet (71 meters) high, the world’s largest Buddha is carved on

the side of an eighth century cliff, looking down on the confluence of

three rivers – the Minjiang, Dadu and Qingyi – in Sichuan province’s

Leshan city. The construction of this statue was started by monk Haitong

in 730 AD and completed in 803 AD by his disciples.

The Great Buddhas of Monywa, Myanmar

© Shutterstock

The massive Buddhist complex, Thanboddhay Pagoda, houses two giant

Buddha statues – one standing and one reclining. The former, built in

1995, is the second tallest Buddha statue in the world at 424 feet

(129.23 meters). It has 31 stories, but there is no tourist access

beyond the 25th floor.

Meanwhile, the reclining Buddha, built in

1991, measures 312 feet (95.09 meters). It has a dark interior, with

etchings that illustrate Buddha’s life, that can be accessed through a

door on the statue’s backside.

The Daibutsu of Kamakura, Japan

© Boonrit Panyaphinitnugoon/Getty Images

The 37-foot-tall (11.4 meters) bronze statue is the second largest

monumental Buddha in the country after the Nara Daibutsu which is nearly

50 feet (15 meters). The statue weighing around 121 tons was completed

in 1252. Initially housed in a huge hall which was washed away by a

tsunami in 1498, it now sits in the open.

Fo Guang Shan, Taiwan

© Fabio Nodari/Getty Images

The largest Buddhist monastery in the country aims to promote a new form

of humanistic Buddhism. Located in Kaohsiung City, it houses a 118-foot

(36-meter) tall statue of Amitabha or “Buddha of Infinite Light,” a

university and various shrines, and covers an area of over 74 acres (30

hectares).

Buddha Dordenma Statue, Bhutan

© Sura Ark/Getty Images

The 167.32-foot-tall (51 meters) statue is made of bronze and gilded in

gold. It is located on a hill in Thimpu, housing 125,000 smaller statues

of Buddha which have been made using the same material. It was

completed in 2015, to mark the 60th birthday of the fourth king of

Bhutan, Jigme Singye Wangchuck.

Laughing Buddha, Vietnam

© J W Alker/imageBROKER/Shutterstock

The Vĩnh Tràng temple in Mekong Delta houses three enormous Buddha

statues among which is the laughing Buddha, symbolizing happiness and

good fortune. Standing out with its big grin and belly, the statue is

particularly popular with young children.

Tian Tan Buddha, Lantau Island, Hong Kong

© Joshua Davenport/REX/Shutterstock

Constructed in 1993, the 111.55-foot-tall (34 meters) bronze statue is

surrounded by six smaller Buddha statues which represent generosity,

morality, patience, zeal, meditation and wisdom. To reach the base of

the huge statue, the visitors need to climb 268 stairs.

Ushiku Daibutsu Buddha, Japan

© Shutterstock

Completed in 1993, the 394-foot-tall (120 meters) bronze statue in

Ibaraki Prefecture depicts Amitabha Buddha. Visitors are permitted to go

up to the observation floor that is 279 feet (85 meters) off the

ground. Except for the top level from where visitors can view the

surrounding areas, other levels are dedicated to music and scriptural

studies.

Ling Shan Great Buddha, China

© Sino Images/Getty Images

Completed in 1996, the bronze statue near Mashan stands 288.71 feet

tall (88 meters) and weighs over 700 tons. It is the center piece of a

Buddhist theme park which comprises Brahma Palace, Nine Dragons Bathing

Sakyamuni, Xiangfu Temple and Five Mudra Mandala.

© Getty Images

Founded in 794, the Buddhist temple is located at Samseong-dong in the

center of Seoul. It is renowned for its “Temple Stay Program” which lets

visitors stay and experience the life of a monk.

TOPICS FOR YOU

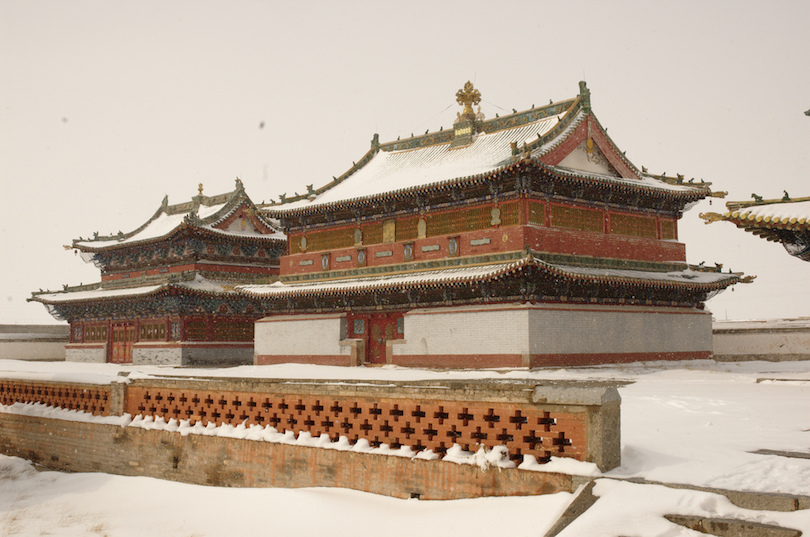

10 Famous Buddhist Temples

Buddhism

is a major world religion and philosophy founded in northeastern India

in the 5th century BC. It is based on the teachings of Siddhartha

Gautama, commonly known as “The Buddha”, who was born in what is today

Nepal. Buddhism takes as its goal the escape from suffering and from the

cycle of rebirth: the attainment of nirvana. There are between 230

million and 500 million Buddhists worldwide. An overview of the most famous Buddhist temples in the world.

14) Classical Basque- Euskal klasikoa,

Esnatuaren Aurkikuntza Unibertsoarekin (DAOAU)

SN 22.59 (S iii 66)

Anattalakkhana Sutta

- Norbere buruaren ezaugarria -

[anattā · lakkhaṇa]

Sutta oso ospetsu honetan, Budak lehen aldiz azaltzen du anattari buruzko irakaskuntza.

Behin batean, Bhagavā Bārāṇasi-n egon zen Isipatanako Deer Grove-n. Han, bost bhikkhus taldeari zuzendu zitzaion:

- Bhikkhus.

- Bhadante, erantzun zuten bhikkhusek. Bhagavak esan zuen:

- Rūpa, bhikkhus, anatta da. Eta rūpa hau atta balitz, bhikkhus, rūpa horrek ez luke bere burua lasaituko, eta [r ]pa esan liteke: ‘Nire rūpa horrela izan dadila, nire rūpa ez dadila horrela izan’. Baina rūpa anatta delako, rūpa bere burua lasaitzeko uzten du eta ezin da [r] esan [r ]pa: ‘Nire rūpa horrela izan dadila, nire rūpa ez dadila horrela izan’.

Vedanā, bhikkhus, anatta da. Eta vedanā hau atta balitz, bhikkhus, vedanā hori ez litzaioke lasaitasuna ematen utziko, eta vedanāri buruz esan liteke: “Nire vedana horrela izan dadila, nire vedana ez dadila horrela izan”. Baina vedanā anatta delako vedanāk lasaitzeko ematen du, eta ezin da vedanā-ri buruz esan: ‘Nire vedana horrela izan dadila, nire vedana ez dadila horrela izan’.

Saññā, bhikkhus, anatta da. Eta saññā hau atta balitz, bhikkhus, saññā hori ez litzaioke erraztasunik emango, eta saññāri buruz esan liteke: ‘Nire saññā horrela izan dadila, nire saññā ez dadila horrela izan’. Saññā anatta delako saññā disgraziorako prest dago eta ezin da saññāri buruz esan: ‘Nire saññā horrela izan dadila, nire saññā ez dadila horrela izan’.

Saṅkhāras, bhikkhus, anatta dira. Eta saṅkhāra horiek atta balira, bhikkhus, saṅkhāra horiek ez lirateke beren burua lasaitzeko prest utziko, eta saṅkhārasi buruz esan liteke: ‘Nire saṅkhrarak horrela izan daitezen, nire saṅkhrarak ez daitezela horrela izan’. Saṅkhāras anatta direlako saṅkhāras lasaitasunerako uzten dute, eta ezin da saṅkhārasi buruz esan: ‘Nire saṅkhāras horrela izan dadila, nire saṅkhrarak ez daitezela horrela izan’.

Viññāṇa, bhikkhus, anatta da. Eta viññāṇa hau atta balitz, bhikkhus, viññāṇa horrek ez luke lasaitasunerako emango, eta viññāṇari buruz esan liteke: “Nire viññāṇa horrela izan dadila, nire viññāṇa ez dadila horrela izan”. Baina viññāṇa anatta delako, viññāṇa bere burua lasaitzeko ematen da, eta ezin da viññā ofaz esan: “Nire viññāṇa horrela izan dadila, ez dadila nire viññāṇa horrela izan”.

Zer deritzozu honi, bhikkhus: Rūpa iraunkorra edo anicca da?

aldi baterako

- Anicca, Bhanthdhe

- Eta anicca dena, dukkha edo sukha da? {1}

- Dukkha, Bhante.

- Eta anicca, dukkha, berez aldatu daitekeen hori, egokia al da honela jotzea: ‘Hau nirea da. Hau naiz. Hau da nire atta? ‘

- Ez, Bhante.

- Vedanā iraunkorra edo anicca al da?

- Anicca, Bhante.

- Eta anicca dena, dukkha edo sukha da?

- Dukkha, Bhante.

- Eta anicca, dukkha, berez aldatu daitekeen hori, egokia al da honela jotzea: ‘Hau nirea da. Hau naiz. Hau da nire atta? ‘

- Ez, Bhante.

- Saññā iraunkorra edo anicca da?

- Anicca, Bhante.

- Eta anicca dena, dukkha edo sukha da?

- Dukkha, Bhante.

- Eta anicca, dukkha, berez aldatu daitekeen hori, egokia al da honela jotzea: ‘Hau nirea da. Hau naiz. Hau da nire atta? ‘

- Ez, Bhante.

- Saṅkhāras iraunkorrak edo anicca al dira?

- Anicca, Bhante.

- Eta anicca dena, dukkha edo sukha da?

- Eta anicca, dukkha dena, aldatu daitekeen izaeraz, egokia al da honela jotzea: ‘Hau nirea da. Hau naiz. Hau da nire atta? ‘

- Ez, Bhante.

- Viññāṇa iraunkorra edo anicca da?

- Anicca, Bhante.

- Eta anicca dena, dukkha edo sukha da?

- Dukkha, Bhante.

- Eta anicca, dukkha dena, aldatu daitekeen izaeraz, egokia al da honela jotzea: ‘Hau nirea da. Hau naiz. Hau da nire atta? ‘

- Ez, Bhante.

- Hori dela eta, bhikkhus, edozein rūpa, iragana, etorkizuna edo oraina, barnekoa edo kanpokoa, gordina edo sotila, beherakoa edo goratua, urruna edo gertu, edozein rūpa yathā · bhūtaṃ paññā egokiarekin ikusi behar da modu honetan: Hau ez da nirea, ni ez naiz hau, hau ez da nire atta ».

Edozein vedanā, iragana, etorkizuna edo oraina, barnekoa edo kanpokoa, gordina edo sotila, beherakoa edo goratua, urruna edo hurbilekoa, edozein vedana yathā · bhūtaṃ paññā egokiarekin ikusi behar da modu honetan: ‘Hau ez da nirea, Ez naiz hau, hau ez da nire atta ».

Saññā edozein dela ere, iragana, etorkizuna edo oraina, barnekoa edo kanpokoa, gordina edo sotila, beherakoa edo goratua, urruna edo gertu, edozein saññā yathā · bhūtaṃ paññā egokiarekin ikusi behar da modu honetan: ‘Hau ez da nirea, Ez naiz hau, hau ez da nire atta ».

Edozein saṅkhāra, izan iragana, etorkizuna edo oraina, barnekoa edo kanpokoa, gordina edo sotila, beheragokoa edo goratua, urruna edo gertu, edozein saṅkhra yathā · bhūtaṃ paññā egokiekin ikusi behar da modu honetan: ‘Hau ez da nirea, Ez naiz hau, hau ez da nire atta ».

Viññāṇa edozein dela ere, iragana, etorkizuna edo oraina, barnekoa edo kanpokoa, gordina edo sotila, beheragokoa edo goratua, urruna edo gertu, edozein viññāṇa yathā · bhūtaṃ paññā egokiarekin ikusi behar da modu honetan: ‘Hau ez da nirea, Ez naiz hau, hau ez da nire atta ».Horrela ikusita, diziplina noble ilustratu bat Rabarekin etsita dago, minarekin pozik, heriotzarekin etsita, chakrarekin etsita eta Viarekin etsita. Etsita, emozional bihurtzen da. Depresioaren bidez, lasaitu egiten da. Askapenarekin, isa: ‘askatu’. Ulertzen du: ‘Jaiotza amaitu da, bizitza braminoa bizi da, egin beharrekoa egina dago, ez dago beste existentziarik’.

Hau da Bhagwarrek esan zuena. Pozik zeuden bost fraideen taldea pozik agertu zen bere hitzekin.

Errebelazio hori eman zenean, bost fraide taldeko zitadelak, itsatsi gabe, heriotzatik libratu ziren.

15) Classical Belarusian-Класічная беларуская,

Адкрыццё Абуджанага з Усведамленнем Сусвету (DAOAU)

SN 22,59 (S iii 66)

Анатталакхана Сута

- Характарыстыка не-Я -

[anattā · lakkhaṇa]

У гэтай вельмі вядомай сутце Буда ўпершыню выкладае сваё вучэнне пра анатту.

Аднойчы Бхагава спыняўся ў Баранасі ў Аленевай гаі ў Ісіпатане. Там ён звярнуўся да групы з пяці бхікху:

- Бхікхус.

- Бхадантэ, - адказалі бхікху. Бхагава сказаў:

- Рупа, бхікхус, анатта. І калі б гэтая рупа была ата, бхікху, гэтая рупа не паддалася б разлад, і пра рупу можна [сказаць]: “Хай мая рупа будзе такой, хай мая рупа не будзе такой.” Але гэта таму, што рупа - гэта анатта, і рупа прыносіць нязручнасць, і гэтага нельга [сказаць] пра рупу: “Хай мая рупа будзе такой, хай мая рупа не будзе такой.”

Ведана, бхікху, - гэта анатта. І калі б гэтая веда была ата, бхікху, гэтая веда не магла б пагоршыць сябе, і пра гэта можна было б сказаць [веда]: “Няхай мая веда будзе такой, хай мая веда не будзе такой”. Але гэта таму, што веда - гэта анатта, - ведана здольная разраджацца, і пра гэта не можа быць сказана: “хай мая веда будзе такой, хай мая веда не будзе такой”.

Саньша, бхікху, - анатта. І калі б гэтая санья была ата, бхікху, гэтая санья не паддалася б непрыемнасцям, і пра гэта можна было б сказаць [санья]: “Хай мая санья будзе такой, хай мая санья не будзе такой”. Але гэта таму, што саньша - гэта анатта, якая дазваляе саннье разладжваць сябе, і яе нельга [сказаць] пра саньсу: “Хай мая санья будзе такой, хай мая санья не будзе такой”.

Сангхары, бхікху, - гэта аната. І калі б гэтыя сангхары былі ата, бхікху, гэтыя сангхары не маглі б сябе здзіўляць, і пра сандхары можна было б [сказаць]: “Няхай мае сангхары будуць такімі, хай мае сангхары не будуць такімі”. Але гэта таму, што сангхары - гэта анатта, з якой сандхары могуць разрадзіцца, і пра сандхары гэтага нельга сказаць: “хай мае сангхары будуць такімі, хай мае сангхары не будуць такімі”.

Віньньяна, бхікху, - гэта анатта. І калі б гэтая віньяна была ата, бхікху, гэтая віньшана не паддалася б разладу, і пра гэта можна было б сказаць [віньяна]: “Няхай мая віньшаня будзе такой, хай мая віньшана не будзе такой”. Але гэта таму, што віньшана - гэта анатта, што віньшаня падвяргаецца нязручнасці, і яе нельга [сказаць] пра віньшану: “Няхай мая віньшаня будзе такой, хай мая віньшана не будзе такой”.

Што вы думаеце пра гэта, бхікху: Рупа пастаянная ці анічка?

часовы

- Аніка, Бхантдэ

- А што анічка, гэта дуккха ці сукха? {1}

- Дукха, Бхантэ.

- І тое, што аніка, дуккха, ад прыроды падвяргаецца зменам, ці правільна гэта лічыць: “Гэта маё. Я гэта. Гэта мой ата?

- Не, Бхантэ.

- Ведана пастаянная альбо аніка?

- Аніка, Бхантэ.

- А што анічка, гэта дуккха ці сукха?

- Дукха, Бхантэ.

- І тое, што аніка, дуккха, ад прыроды падвяргаецца зменам, ці правільна лічыць гэта: “Гэта маё. Я гэта. Гэта мой ата?

- Не, Бхантэ.

- Санья пастаянная альбо аніка?

- Аніка, Бхантэ.

- А што анічка, гэта дуккха ці сукха?

- Дукха, Бхантэ.

- І тое, што аніка, дуккха, ад прыроды падвяргаецца зменам, ці правільна лічыць гэта: “Гэта маё. Я гэта. Гэта мой ата?

- Не, Бхантэ.

- Сангхарас пастаянны альбо аніка?

- Аніка, Бхантэ.

- А што анічка, гэта дуккха ці сукха?

- І тое, што аніка, дуккха, ад прыроды падвяргаецца зменам, ці правільна лічыць гэта: “Гэта маё. Я гэта. Гэта мой ата?

- Не, Бхантэ.

- Віньшана пастаянная альбо аніка?

- Аніка, Бхантэ.

- А што анічка, гэта дуккха ці сукха?

- Дукха, Бхантэ.

- І тое, што анікка, дуккха, ад прыроды падвяргаецца зменам, ці правільна гэта лічыць: “Гэта маё. Я гэта. Гэта мой ата?

- Не, Бхантэ.

- Такім чынам, бхікху, незалежна ад рупы, няхай гэта будзе мінулая, будучая альбо цяперашняя, унутраная альбо знешняя, грубая ці тонкая, непаўнавартасная альбо ўзнёслая, далёкая альбо блізкая, любую рупу трэба разглядаць ятха · бхутаṃ з належнай паньшнай такім чынам: ‘ Гэта не маё, я не гэта, гэта не маё ата “.

Незалежна ад веданы, няхай гэта будзе мінулая, будучая ці цяперашняя, унутраная альбо знешняя, грубая ці тонкая, непаўнавартасная альбо ўзнёслая, далёкая ці блізкая, любую ведану трэба разглядаць ятха · бхутаṃ з належным паньшам такім чынам: «Гэта не маё, Я не гэта, гэта не мой ата ‘.

Якая б ні была саньша, няхай гэта будзе мінулая, будучая ці цяперашняя, унутраная альбо знешняя, грубая ці тонкая, непаўнавартасная альбо ўзнёслая, далёкая ці блізкая, любую саньшу трэба разглядаць ятха · бхутаṃ з належнай панньёй такім чынам: Я не гэта, гэта не мая атака “.

Якімі б не былі санхары, няхай яны будуць мінулымі, будучымі альбо сапраўднымі, унутранымі альбо знешнімі, грубымі ці тонкімі, непаўнавартаснымі альбо ўзнёслымі, далёкімі ці блізкімі, любых сангхараў трэба разглядаць ятха · бхутаṃ з належнымі паньшамі такім чынам: ‘Гэта не маё Я не гэта, гэта не мая атака “.

Незалежна ад віньшаны, няхай гэта будзе мінулая, будучая ці цяперашняя, унутраная ці знешняя, грубая ці тонкая, непаўнавартасная альбо ўзнёслая, далёкая ці блізкая, любую віньшану трэба разглядаць ятха · бхутаю з належнай паньшай такім чынам: ‘Гэта не маё, Я не гэта, гэта не мая атака “.У такім выглядзе прасветлены высакародны вучань расчараваны Рабай, незадаволены болем, расчараваны смерцю, расчараваны чакрамі і расчараваны Віяй. Расчараваны, ён становіцца эмацыянальным. Праз дэпрэсію ён адчувае палёгку. З вызваленнем, isa: “вызвалены”. Ён разумее: “Нараджэнне скончылася, жыццё брахмана пражыта, зроблена тое, што трэба зрабіць, нічога іншага для гэтага існавання няма”.

Гэта сказаў Бхагвар. Група пяці манахаў, якія былі ў захапленні, была ў захапленні ад яго слоў.

Калі было дадзена гэтае адкрыццё, цытадэлі групы пяці манахаў, не прыліпаючы, былі вызвалены ад смерці.

16) Classical Bengali-ক্লাসিক্যাল বাংলা,

সচেতনতা ইউনিভার্স (ডিএওএইউ) দিয়ে জাগ্রত ব্যক্তির আবিষ্কার

এসএন 22.59 (এস আইআইআই 66)

আনতলখনা সুত্ত

- স্ব-স্ব বৈশিষ্ট্য -

[আনতাā লক্ষখা]

অত্যন্ত বিখ্যাত এই সূত্রে বুদ্ধ প্রথমবার অনাতায় তাঁর শিক্ষার ব্যাখ্যা দিয়েছিলেন।

একসময়, ভগবতা ইসিপাতানার হরিণ গ্রোভের বরসিয়াসে অবস্থান করছিলেন। সেখানে তিনি পাঁচটি ভিক্ষু দলকে সম্বোধন করেছিলেন:

- ভিক্ষুস

- ভাদান্তে, ভিক্ষু জবাব দিল। ভাগব বলেছেন:

- রেপা, ভিক্ষুস, আনাত্তা। আর যদি এই রাপা আতা, ভিক্ষুস হত তবে এই রাপা নিজেকে অনর্থক-স্বাচ্ছন্দ্যে leণ দিতেন না, এবং রাপা সম্পর্কে বলা যেতে পারে: ‘আমার রাপা যেন এমন হয়, আমার রাপা যেন এমন না হয়।’ তবে এ কারণেই রাপা অনাত্ত্র যা রাপা নিজেকে অনিচ্ছায়িত করার জন্য ঘৃণা করে, আর এটিকে রাপা সম্পর্কে বলা যায় না: ‘আমার রাপা যেন এমন হয়, আমার রাপা যেন এমন না হয়।’

বেদনা, ভিক্ষুস, আনাত্তা। এবং যদি এই বেদানা আতা, ভিক্ষুস হত তবে এই বেদানাটি নিজেকে সহজেই অনর্থক toণ দিতো না, এবং বেদানের কথাও বলা যেতে পারে: ‘আমার বেদানা যেন এমন হয় তবে আমার বেদনা এমন না হয়।’ তবে এটি বেদানাট হ’ল আনাট্ট যা বেদানা নিজেকে অবিরাম করতে ঘৃণা করে এবং বেদ সম্পর্কে [তা বলা যায় না]: ‘আমার বেদানা যেন এমন হয়, আমার বেদনা এমন না হয়।’

সাঃ, ভিক্ষুস, আনাত্তা। আর যদি এই সাতা আতা, ভিক্ষুস হত তবে এই সা’আ নিজেকে অবিরাম করতে ঘৃণা করতেন না, এবং এটি সা’য়ের কথা বলা যেতে পারে: ‘আমার সা’টা যেন এমন হয়, আমার সা’টা এমন না হয়।’ তবে এটি হ’ল অনাটি হ’ল সাঁতা নিজেকে অস্বাচ্ছন্দ্যের জন্য ndsণ দেয় এবং এটি ‘সা’-এর বিষয়ে বলা যায় না:’ আমার সা’টা যেন এমন হয়, আমার সা’টা এমন না হয়। ‘

সখরাস, ভিক্ষুস, আনাত্তা। আর যদি এই সখররা আতা, ভিক্ষুস হত তবে এই সখরাশরা নিজেদেরকে অনিচ্ছার জন্য ndণ দিত না, এবং সখখরাস সম্পর্কে [বলা যেতে পারে): ‘আমার সখরাশরা যেন এ রকম হয় তবে আমার সখরাশরা এ রকম না হয়।’ তবে এটি কারণ, কারণ সখররা অনত হ’ল যে সখররা নিজেকে অনাচারের জন্য leণ দেয়, এবং এটি সখখরাস সম্পর্কে বলা যায় না: ‘আমার সখরাশরা যেন এমন হয়, আমার সখরাশরা এ রকম না হয়।’

ভাইয়া, ভিক্ষুস, আনাত্তা। আর যদি এই ভাইটা আতা, ভিক্ষুস হত তবে এই ভাইয়া নিজেকে সহজেই অনর্থক বলে মনে করত না, এবং ভাইয়ার কথাও বলা যেতে পারে: ‘আমার ভাইয়া যেন এমন হয়, আমার ভাইয়া এমন না হয়।’ তবে এটি হ’ল অনাটি হ’ল যে ভাইয়া নিজেকে সহজেই অদৃশ্য করার জন্য ññāṇণ দেয় এবং এটি ভাইয়ার বিষয়ে [বলা যায় না]: ‘আমার ভাইয়া এমনভাবেই হোক, আমার ভাইয়া এমনভাবে না ঘটে।’

এই সম্পর্কে আপনার কী ধারণা, ভখখুস: রাপা স্থায়ী নাকি অ্যানিক্কা?

অস্থায়ী

- আনিকা, ভান্থে

- আর যা আনিচা, তা কি দুখখা নাকি সুখ? {1}

- দুখখা, ভাঁতে।

- এবং যা অনীক, দুখা, প্রকৃতির পরিবর্তনের সাপেক্ষে, এটিকে বিবেচনা করা কি যথাযথ: ‘এটি আমার। আমি এই। এটা আমার আতা? ‘

- না, ভাঁতে।

- বেদান স্থায়ী নাকি অ্যানিকা?

- আনিকা, ভাঁতে।

- আর যা আনিচা, তা কি দুখখা নাকি সুখ?

- দুখখা, ভাঁতে।

- এবং যা অনীক, দুখ, প্রকৃতির পরিবর্তনের সাপেক্ষে, এটিকে বিবেচনা করা কি যথাযথ: ‘এটি আমার। আমি এই। এটা আমার আতা? ‘

- না, ভাঁতে।

- সাññā স্থায়ী নাকি অ্যানিকা?

- আনিকা, ভাঁতে।

- আর যেটা আনিচা, তা কি দুখখা নাকি সুখ?

- দুখখা, ভাঁতে।

- এবং যা অনীক, দুখ, প্রকৃতির পরিবর্তনের সাপেক্ষে, এটিকে বিবেচনা করা কি যথাযথ: ‘এটি আমার। আমি এই। এটা আমার আতা? ‘

- না, ভাঁতে।

- সখরাস কি স্থায়ী নাকি অ্যানিকা?

- আনিকা, ভাঁতে।

- আর যেটি আনিচা, তা কি দুখখা নাকি সুখ?

- এবং যা অনীক, দুখা, প্রকৃতির পরিবর্তনের সাপেক্ষে, এটিকে বিবেচনা করা কি যথাযথ: ‘এটি আমার। আমি এই। এটা আমার আতা? ‘

- না, ভাঁতে।

- ভাইয়া কি স্থায়ী নাকি অ্যানিকা?

- আনিকা, ভাঁতে।

- আর যেটা আনিচা, তা কি দুখখা নাকি সুখ?

- দুখখা, ভাঁতে।

- এবং যা অনীক, দুখা, প্রকৃতির পরিবর্তনের সাপেক্ষে, এটিকে বিবেচনা করা কি যথাযথ: ‘এটি আমার। আমি এই। এটা আমার আতা? ‘

- না, ভাঁতে।

- অতএব, ভিক্ষুস, যা-ই হোক না কেন, তা অতীত, ভবিষ্যত, বা বর্তমান, অভ্যন্তরীণ বা বাহ্যিক, স্থূল বা সূক্ষ্ম, নিকৃষ্ট বা উচ্চতর, দূর বা নিকটবর্তী, কোনও রাপকে যথাযথ পাঠের সাথে এইভাবেই দেখতে পাওয়া যায়: ‘ এটি আমার নয়, আমি এটি নই, এটি আমার আতা নয় ‘’

বেদনা যাই হউক না কেন, অতীত, ভবিষ্যত বা বর্তমান, অভ্যন্তরীণ বা বাহ্যিক, স্থূল বা সূক্ষ্ম, নিকৃষ্ট বা উচ্চতর, সুদূর বা নিকটবর্তী, যে কোনও বেদানকে যথাযথ পন্থায় ইয়াত ভক্তকে দেখা যেতে পারে: ‘এটি আমার নয়, আমি এটি নই, এটি আমার আতা নয়। ‘

যাই হোক না কেন, তা অতীত, ভবিষ্যত বা বর্তমান, অভ্যন্তরীণ বা বাহ্যিক, স্থূল বা সূক্ষ্ম, নিকৃষ্ট বা উচ্চতর, সুদূর বা নিকটবর্তী, যে কোনও সাথকে যথাযথ পায়ের সাথে এইভাবে দেখা যেতে হবে: ‘এটি আমার নয়, আমি এটি নই, এটি আমার আতা নয়। ‘

যেই সখীরা হোক না কেন, সেগুলি অতীত, ভবিষ্যত বা বর্তমান, অভ্যন্তরীণ বা বাহ্যিক, স্থূল বা সূক্ষ্ম, নিকৃষ্ট বা উচ্চতর, সুদূর বা নিকটেই হোক, যে কোনও সখরীরা এইভাবে যথাযথ পন্থায় ইয়াতভক্তকে দেখা যাবে: ‘এটি আমার নয়, আমি এটি নই, এটি আমার আতা নয়। ‘

যেকোনো viia, তা অতীত, ভবিষ্যত বা বর্তমান, অভ্যন্তরীণ বা বাহ্যিক, স্থূল বা সূক্ষ্ম, নিকৃষ্ট বা উচ্চতর, সুদূর বা নিকটবর্তী, যে কোনও ভাইকে যথাযথ পায়ের সাথে ইয়াত ভক্তকে দেখা উচিত: ‘এটি আমার নয়, আমি এটি নই, এটি আমার আতা নয়। ‘এইভাবে দেখা যায়, একজন আলোকিত আভিজাত্য শিষ্য রাবার সাথে হতাশ, বেদনায় অসন্তুষ্ট, মৃত্যুর সাথে হতাশ, চক্রে হতাশ এবং ভায়ার সাথে হতাশ। হতাশ হয়ে সে আবেগপ্রবণ হয়। হতাশার মধ্য দিয়ে তিনি মুক্তি পান। মুক্তির সাথে, ইসা: ‘মুক্তি পেয়েছে।’ তিনি বুঝতে পেরেছেন: ‘জন্ম শেষ, ব্রাহ্মণ জীবন বেঁচে আছে, যা করা দরকার তা করা হয়, এই অস্তিত্বের আর কিছুই নেই।’

ভগবান এই বলেছিলেন। তাঁর কথায় খুশি হয়েছিলেন পাঁচটি সন্ন্যাসীর দল।

যখন এই ওহী দেওয়া হয়েছিল, পাঁচটি সন্ন্যাসীর দলটির সিটিডেলগুলি, লাঠি না ধরেই মৃত্যু থেকে মুক্তি পেয়েছিল।

17) Classical Bosnian-Klasični bosanski,

Otkrivanje Probuđenog sa Univerzumom svjesnosti (DAOAU)

SN 22,59 (S iii 66)

Anattalakkhana Sutta

- Karakteristika ne-Ja -

[anatha · lakkhaṇa]

U ovoj vrlo poznatoj sutti, Buda prvi put iznosi svoje učenje o anatti.

Jednom prilikom, Bhagavā je boravio u Bārāiasiju u Jelenovom gaju u Isipatani. Tamo se obratio grupi od pet monahinja:

- Bhikkhus.

- Bhadante, odgovorili su monahši. Bhagava je rekao:

- Rupa, monah, je anatta. A da je ova rupa Atta, monahinje, ova rupa se ne bi mogla smiriti, a moglo bi se [reći] i za Rupu: ‘Neka moja rupa bude takva, neka moja rupa ne bude takva.’ Ali zato što je rūpa anatta, rūpa se može ometati i što se to ne može [reći] za rūpu: ‘Neka moja rupa bude takva, neka moja rupa ne bude takva.’

Vedana, monahinja, je anatta. I kad bi ova vedana bila Atta, monahinje, ova vedana ne bi mogla da se ometa, a moglo bi se [reći] i o vedani: ‘Neka moja vedana bude takva, neka moja vedana ne bude takva.’ Ali to je zato što je vedana anatta, što se vedano može smiriti i što se za nju ne može [reći]: ‘Neka moja vedana bude takva, neka moja vedana ne bude takva.’

Saññā, monah, je anatta. A da je ova sañña Atta, monahinje, ova sañña se ne bi mogla smiriti, a za saññu bi se moglo [reći]: ‘Neka moja sñña bude takva, neka moja sñña ne bude takva.’ Ali zato što je saññā anatta, sañña sebi daje smetnju i što se za saññu ne može [reći]: ‘Neka moja sññā bude takva, neka moja sññā ne bude takva.’

Saṅkhāras, monahinje, su anatta. A da su ti sandžare bili Atta, monahinje, ti sandžare ne bi se odavali, a moglo bi se [reći] za sandžare: ‘Neka moji sandžare budu takvi, neka moji sandžare ne budu takvi.’ Ali zato što su sandžare anatta, sandžare se mogu smiriti i što se ne može [reći] za sandžare: ‘Neka moje sandžare budu takve, neka moje sandžare ne budu takve.’

Viññāṇa, monahinja, je anatta. I da je ova vinjana Atta, monahinje, ova vinjana se ne bi mogla smiriti, a moglo bi se [reći] i o vinjani: ‘Neka moja viññāṇa bude takva, neka moja viññā’a ne bude takva.’ Ali zato što je viññāṇa anatta, viññāṇa se odaje nelagodnosti i što se to ne može [reći] za viññāṇa: „Neka moja viññāṇa bude takva, neka moja viññāṇa ne bude takva.“

Što mislite o ovome, monahinje: je li Rupa trajna ili anicca?

privremeni

- Anicca, Bhanthdhe

- A ono što je anicca, je li dukkha ili sukha? {1}

- Dukkha, Bhante.

- A ono što je anicca, dukkha, po prirodi podložno promjenama, je li ispravno smatrati to: ‘Ovo je moje. Ja sam ovo. Ovo je moj napadač? ‘

- Ne, Bhante.

- Da li je Vedanā trajna ili anicca?

- Anicca, Bhante.

- A ono što je anicca, je li dukkha ili sukha?

- Dukkha, Bhante.

- A ono što je anicca, dukkha, po prirodi podložno promjenama, je li ispravno smatrati to: ‘Ovo je moje. Ja sam ovo. Ovo je moj napadač? ‘

- Ne, Bhante.

- Da li je Saññā trajna ili anicca?

- Anicca, Bhante.

- A ono što je anicca, je li dukkha ili sukha?

- Dukkha, Bhante.

- A ono što je anicca, dukkha, po prirodi podložno promjenama, je li ispravno smatrati to: ‘Ovo je moje. Ja sam ovo. Ovo je moj napadač? ‘

- Ne, Bhante.

- Jesu li Saṅkhāras trajni ili anicca?

- Anicca, Bhante.

- A ono što je anicca, je li dukkha ili sukha?

- A ono što je anicca, dukkha, po prirodi podložno promjenama, je li ispravno smatrati to: ‘Ovo je moje. Ja sam ovo. Ovo je moj napadač? ‘

- Ne, Bhante.

- Da li je Viññāṇa trajna ili anicca?

- Anicca, Bhante.

- A ono što je anicca, je li dukkha ili sukha?

- Dukkha, Bhante.

- A ono što je anicca, dukkha, po prirodi podložno promjenama, je li ispravno smatrati to: ‘Ovo je moje. Ja sam ovo. Ovo je moj napadač? ‘

- Ne, Bhante.

- Stoga, monahse, bilo koje rupe, bilo da je prošla, buduća ili sadašnja, unutarnja ili vanjska, gruba ili suptilna, inferiorna ili uzvišena, daleka ili blizu, bilo koju rupu treba vidjeti yathā · bhūtaṃ s odgovarajućim paññā na ovaj način: ‘ Ovo nije moje, nisam ovo, ovo nije moj napad. ‘

Kakva god bila vedana, bila ona prošla, buduća ili sadašnja, unutarnja ili vanjska, gruba ili suptilna, inferiorna ili uzvišena, daleka ili blizu, bilo koju vedanu treba vidjeti yathā · bhūtaṃ s odgovarajućim paññā na ovaj način: ‘Ovo nije moje, Ja nisam ovo, ovo nije moj napadač. ‘

Bez obzira na saññu, bila ona prošlost, budućnost ili sadašnjost, unutarnja ili vanjska, gruba ili suptilna, inferiorna ili uzvišena, daleka ili blizu, bilo koju sññu treba vidjeti yathā · bhūtaṃ s odgovarajućom paññom na ovaj način: ‘Ovo nije moje, Ja nisam ovo, ovo nije moj napadač. ‘

Bez obzira na saṅkhāre, bile one prošle, buduće ili sadašnje, unutarnje ili vanjske, grube ili suptilne, inferiorne ili uzvišene, daleke ili bliske, bilo koje sṅkhāre treba vidjeti yathā · bhūtaṃ s odgovarajućim paññama na ovaj način: „Ovo nije moje, Ja nisam ovo, ovo nije moj napadač. ‘

Kakva god viññāṇa, bila ona prošlost, budućnost ili sadašnjost, unutarnja ili vanjska, gruba ili suptilna, inferiorna ili uzvišena, daleka ili blizu, bilo koju viññāṇu treba vidjeti yathā · bhūtaṃ s odgovarajućim paññā na ovaj način: „Ovo nije moje, Ja nisam ovo, ovo nije moj napadač. ‘Tako gledano, prosvijetljeni plemeniti učenik razočaran je Rabom, nezadovoljan bolom, razočaran smrću, razočaran čakrama i razočaran Via. Razočaran, postaje emotivan. Kroz depresiju mu je laknulo. Oslobođenjem je: ‘oslobođeno’. Razumije: ‘Rođenje je gotovo, život brahmana je prošao, ono što treba učiniti je učinjeno, za ovo postojanje nema ništa drugo.’

Ovo je rekao Bhagwar. Skupinu od pet monaha koji su bili oduševljeni oduševile su njegove riječi.

Kada je dato ovo otkrivenje, kašteli grupe od pet monaha, bez držanja, oslobođeni su smrti.

18) Classical Bulgaria- Класически българск,

Откриване на пробуден с Вселената на осъзнаването (DAOAU)

SN 22,59 (S iii 66)

Anattalakkhana Sutta

- Характеристиката на не-Аз-а -

[anattā · lakkhaṇa]

В тази много известна сута Буда за първи път излага своето учение за анатта.

Веднъж Бхагава отседнал в Баранаши в Еленската горичка в Исипатана. Там той се обърна към групата от петима мохаджи:

- Bhikkhus.

- Бхаданте, отвърнаха момчетата. Бхагава каза:

- Rūpa, bhikkhus, е анатта. И ако тази рупа беше ата, бхикху, тази рупа нямаше да се поддава на неспокойствие и би могло да се каже за рупа: „Нека моята рупа бъде такава, нека моята рупа не бъде такава.“ Но тъй като рупа е анатта, рупата се поддава на неспокойствие и че не може да се [казва] за рупа: „Нека моята рупа бъде такава, нека моята рупа не бъде такава.“

Ведана, бхикхус, е анатта. И ако тази ведана беше ата, бхикху, тази веда не би се поддала на неспокойствие и би могло [да се каже] за ведана: „Нека моята веда бъде такава, нека моята ведана не бъде такава“. Но тъй като vedana е anatta, vedanā се поддава на неспокойствие и че не може [да се каже] за vedanā: „Нека моя vedanā бъде такава, нека моя vedanā не бъде такава“.

Saññā, bhikkhus, е анатта. И ако тази саня беше ата, бхикху, тази саня не би се поддала на неспокойствие и би могло [да се каже] за саня: „Нека моята саня бъде такава, нека моята саня не бъде такава“. Но тъй като saññā е anatta, saññā се поддава на безпокойство и че не може [да се каже] за saññā: „Нека saññā бъде такъв, нека saññā не бъде такъв“.

Сангхари, бхикху, са анатта. И ако тези санджари бяха ата, монах, тези сангхари нямаше да се поддават на неспокойствие и за сандхарите може да се [каже]: „Нека моите санджари бъдат такива, нека моите санджари не бъдат такива“. Но защото сангхарите са анатта, санджарите се поддават на неспокойствие и че не може [да се каже] за санджарите: „Нека моите санджари бъдат такива, нека моите санджари не бъдат такива“.

Viññāṇa, bhikkhus, е анатта. И ако тази виншана беше ата, мохуси, тази виньшана нямаше да се поддава на безпокойство и би могло [да се каже] на виншаня: „Нека моята виньшана да бъде такава, нека моята виньшана не бъде такава“. Но тъй като виншана е анатта, той се поддава на неспокойствие и че не може [да се каже] за виншаня: „Нека моята виньша бъде такава, нека моята виньшана не бъде такава“.

Какво мислите за това, монахини: Рупа постоянна ли е или аника?

временно

- Аника, Бхантхе

- А това, което е аника, дуккха или сукха? {1}

- Dukkha, Bhante.

- И това, което е anicca, dukkha, по природа подлежи на промяна, правилно ли е да го считаме като: „Това е мое. Аз съм това. Това е моят ата?

- Не, Бханте.

- Vedanā постоянна ли е или anicca?

- Аника, Бханте.

- А това, което е аника, дукха или сукха?

- Dukkha, Bhante.

- И това, което е anicca, dukkha, по природа подлежи на промяна, правилно ли е да го считаме като: „Това е мое. Аз съм това. Това е моят ата?

- Не, Бханте.

- Saññā постоянна ли е или anicca?

- Аника, Бханте.

- А това, което е аника, дуккха или сукха?

- Dukkha, Bhante.

- И това, което е anicca, dukkha, по природа подлежи на промяна, правилно ли е да го разглеждаме като: „Това е мое. Аз съм това. Това е моят ата?

- Не, Бханте.

- Saṅkhāras постоянни ли са или anicca?

- Аника, Бханте.

- А това, което е аника, дуккха или сукха?

- И това, което е anicca, dukkha, по природа подлежи на промяна, правилно ли е да го считаме като: „Това е мое. Аз съм това. Това е моят ата?

- Не, Бханте.

- Постоянна ли е Viññāṇa или anicca?

- Аника, Бханте.

- А това, което е аника, дуккха или сукха?

- Dukkha, Bhante.

- И това, което е anicca, dukkha, по природа подлежи на промяна, правилно ли е да го считаме като: „Това е мое. Аз съм това. Това е моят ата?

- Не, Бханте.

- Следователно, бхикху, каквато и да е рупа, била тя минала, бъдеща или настояща, вътрешна или външна, груба или фина, по-ниска или извисена, далечна или близка, всяка рупа трябва да се разглежда yathā · bhūtaṃ с подходящи paññā по този начин: “ Това не е мое, аз не съм това, това не е моето ата. ‘

Каквато и да е ведана, била тя минала, бъдеща или настояща, вътрешна или външна, груба или фина, по-ниска или екзалтирана, далечна или близка, всяка ведана трябва да се вижда ятха · бхутаṃ с подходяща паньша по този начин: „Това не е мое, Аз не съм това, това не е моят ата.

Каквато и да е саня, била тя минала, бъдеща или настояща, вътрешна или външна, груба или фина, по-ниска или възвишена, далечна или близка, всяка саня трябва да се разглежда yathā · bhūtaṃ с подходяща paññā по този начин: „Това не е мое, Аз не съм това, това не е моят ата.

Каквито и санджари, били те минали, бъдещи или настоящи, вътрешни или външни, груби или фини, по-ниски или възвишени, далечни или близки, всички санджари трябва да се видят ятха · бхутаṃ с подходящи панджа по този начин: „Това не е мое, Аз не съм това, това не е моята атака.

Каквато и да е виннаша, била тя минала, бъдеща или настояща, вътрешна или външна, груба или фина, по-ниска или извисена, далечна или близка, всяка виньшана трябва да се види ятха · бхутаṃ с подходяща паня по този начин: „Това не е мое, Аз не съм това, това не е моят ата.Погледнат по този начин, просветеният благороден ученик е разочарован от Раба, недоволен от болка, разочарован от смъртта, разочарован от чакрите и разочарован от Виа. Разочарован, той става емоционален. Чрез депресия той се облекчава. С освобождението, isa: „освободен“. Той разбира: „Раждането е приключило, животът на брамин е изживян, това, което трябва да се направи, е направено, няма нищо друго за това съществуване“.

Това каза Бхагвар. Групата от петима монаси, които бяха във възторг, бяха възхитени от думите му.

Когато това откровение беше дадено, цитаделите на групата от петима монаси, без да се придържат, бяха освободени от смъртта.

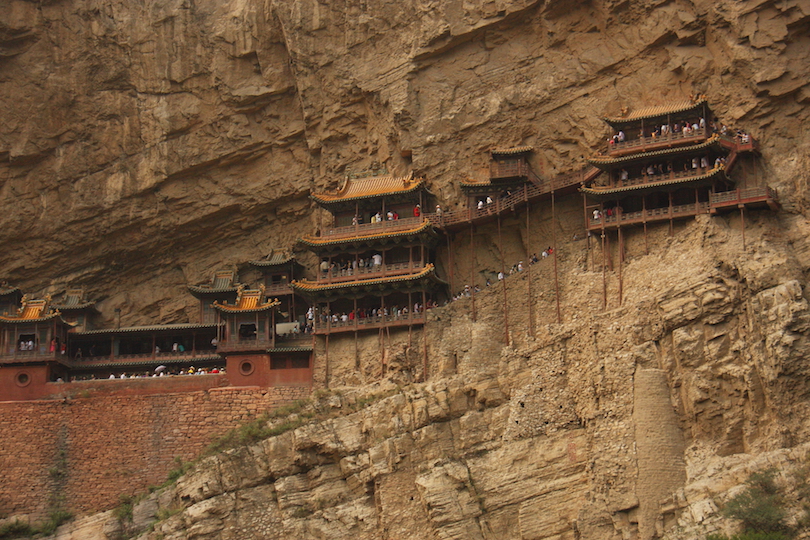

10. Haeinsa Temple

Haeinsa (Temple of Reflection on a Smooth Sea) is one of the most

important Buddhist temples in South Korea. The temple was first built in

802 and rebuilt in the 19th century after Haiensa was burned down in a

fire in 1817. The temple’s greatest treasure however, a complete copy of

the Buddhist scriptures (he Tripitaka Koreana) written on 81,258

woodblocks, survived the fire.

9. Wat Arun

Situated on the Thonburi side of the Chao Phraya River , Wat Arun (“Temple of Dawn”) is one of the oldest and best known landmarks in Bangkok,

Thailand. The temple is an architectural representation of Mount Meru,

the center of the universe in Buddhist cosmology. Despite it’s name, the

best views of Wat Arun are in the evening with the sun setting behind

it.

8. Pha That Luang

flickr/A_E_P

flickr/A_E_PLocated in Vientiane, Pha That Luang (“Great Stupa in Lao”) is one of the most important monument in Laos.

The stupa has several terraces with each level representing a different

stage of Buddhist enlightenment. The lowest level represents the

material world; the highest level represents the world of nothingness.

Pha That Luang was built in the 16th century on the ruins of an earlier

Khmer temple. The temple was destroyed by a Siamese invasion in 1828,

then later reconstructed by the French in 1931.

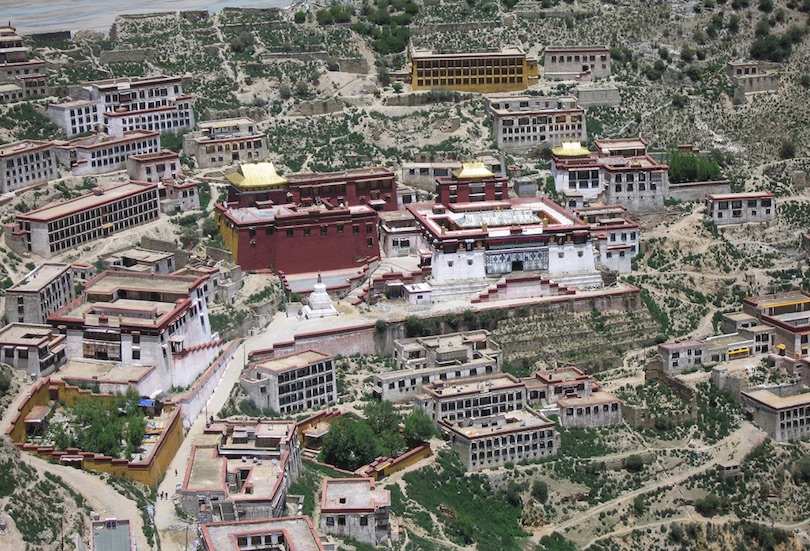

7. Jokhang

The Jokhang Temple in Lhasa

is the most important sacred site in Tibetan Buddhism attracting

thousands of pilgrims each year. The temple was constructed by King

Songtsän Gampo in the 7th century. The Mongols sacked the Jokhang temple

several times but the building survived. Today the temple complex

covers an area of about 25,000 square meters.

6. Todaiji Temple

flickr/roybuloy

flickr/roybuloyTodaiji (“Great Eastern Temple”) in Nara is one of the most historically significant and famous Buddhist temples in Japan.

The temple was built in the 8th century by Emperor Shomu as the head

temple of all provincial Buddhist temples of Japan. Today little remains

of the original buildings of Todaiji. The Daibutsuden (“Great Buddha

Hall”), dates for the most part from 1709. It houses one of the largest

Budha statues in Japan and is the worlds largest wooden building, even

though it is only two-thirds the size of the original structure.

5. Boudhanath

Located in a suburb of Kathmandu,

Boudhanath is one of the largest stupas in the world. It is the center

of Tibetan Buddhism in Nepal and many refugees from Tibet have settled

here in the last few decades. It is probably best known for the Buddha

eyes that are featured on all four sides of the tower. The present stupa

is said to date from the 14th century, after the previous one was

destroyed by Mughal invaders.

4. Mahabodhi Temple

The Mahabodhi (Great Enlightenment) Temple is a Buddhist stupa

located in Bodh Gaya, India. The main complex contains a descendant of

the original Bodhi Tree under which Gautama Buddha gained enlightenment

and is the most sacred place in Buddhism. About 250 years after the

Buddha attained Enlightenment, Emperor Asoka built a temple at the spot.

The present temple dates from the 5th-6th century.

3. Shwedagon Pagoda

The Shwedagon Pagoda (or Golden Pagoda) in Yangon, is the holiest

Buddhist shrine in Burma. The origins of Shwedagon are lost in antiquity

but it is estimated that the Pagoda was first built by the Mon during

the Bagan period, sometime between the 6th and 10th century AD. The

temple complex is full of glittering, colorful stupas but the center of

attention is the 99 meter high (326 feet) high main stupa that is

completely covered in gold.

2. Bagan

Bagan, also spelled Pagan, on the banks of the Ayerwaddy River, is

home to the largest area of Buddhist temples, pagodas, stupas and ruins

in the world. It was the capital of several ancient kings of Burma who

built perhaps as many as 4,400 temples during the height of the kingdom

(between 1000 and 1200 AD). In 1287, the kingdom fell to the Mongols,

after refusing to pay tribute to Kublai Khan and Bagan quickly declined

as a political center, but continued to flourish as a place of Buddhist

scholarship.

1. Borobudur

Located on the Indonesian island of Java, 40 km (25 miles) northwest

of Yogyakarta, the Borobudur is the largest and most famous Buddhist

temple in the world. The Borobudur was built over a period of some 75

years in the 8th and 9th centuries by the kingdom of Sailendra, out of

an estimated 2 million blocks of stone. It was abandoned in the 14th

century for reasons that still remain a mystery and for centuries lay

hidden in the jungle under layers of volcanic ash.

19) Classical Catalan-Català clàssic,

Descobriment d’un despert amb univers de consciència (DAOAU)

SN 22,59 (S iii 66)

Anattalakkhana Sutta

- La característica del no-jo -

[anattā · lakkhaṇa]

En aquest famós sutta, Buda exposa per primera vegada el seu ensenyament sobre anatta.

En una ocasió, el Bhagavā s’allotjava a Bārāṇasi, al Deer Grove, a Isipatana. Allà, es va dirigir al grup de cinc monjos:

- Monjos.

- Bhadante, van respondre els monjos. El Bhagavā va dir:

- Rūpa, monjos, és anatta. I si aquesta rūpa fos atta, bhikkhus, aquesta rūpa no es prestaria a la tranquil·litat i es podria [dir] de rūpa: “Que la meva rūpa sigui així, que la meva rūpa no sigui així”. Però és perquè rūpa és un anatta que rūpa es presta a la tranquil·litat i que no es pot [dir] de rūpa: “Que la meva rūpa sigui així, que la meva rūpa no sigui així”.

Vedanā, monjos, és un anatta. I si aquest vedanā fos atta, bhikkhus, aquest vedanā no es prestaria a la tranquil·litat i es podria [dir] de vedanā: “Que el meu vedanà sigui així, que el meu vedanà no sigui així”. Però és perquè vedanā és un anatta que vedanā es presta a la tranquil·litat i que no es pot [dir] de vedanā: “Que el meu vedanà sigui així, que el meu vedanà no sigui així”.

Saññā, monjos, és un anatta. I si aquest saññā fos atta, bhikkhus, aquest saññā no es prestaria a la tranquil·litat i es podria [dir] de saññā: “Que el meu saññā sigui així, que el meu saññā no sigui així”. Però és perquè saññā és una anatta que saññā es presta a la tranquil·litat i que no es pot [dir] de saññā: “Que el meu saññā sigui així, que el meu saññā no sigui així”.

Saṅkhāras, bhikkhus, són anatta. I si aquests saṅkhāras fossin atta, bhikkhus, aquests saṅkhāras no es prestarien a la tranquil·litat i es podria [dir] de saṅkhāras: “Que els meus saṅkhāras siguin així, que els meus saṅkhāras no siguin així”. Però és perquè els saṅkhāras són anatta que els saṅkhāras es presten a la tranquil·litat, i que no es pot [dir] de saṅkhāras: “Que els meus saṅkhāras siguin així, que els meus saṅkhras no siguin així”.

Viññāṇa, monjos, és un anatta. I si aquest viññāṇa fos atta, bhikkhus, aquest viññā nota no es prestaria a la tranquil·litat i es podria [dir] de viññāṇa: “Que el meu viññāṇa sigui així, que el meu viññāṇa no sigui així”. Però és perquè viññāṇa és una anatta que viññāṇa es presta a la tranquil·litat i que no es pot [dir] de viññāṇa: “Que el meu viññāṇa sigui així, que el meu viññāṇa no sigui així”.

Què en penseu, monjos: Rūpa és permanent o anicca?

temporal

- Anicca, Bhanthdhe

- I el que és anicca, és dukkha o sukha? {1}

- Dukkha, Bhante.

- I allò que és anicca, dukkha, per naturalesa subjecte a canvis, és adequat considerar-lo com: ‘Això és meu. Jo sóc això. Aquesta és la meva atta?

- No, Bhante.