03/24/18

Filed under:

General

Posted by:

site admin @ 9:14 pm

2571 Sun 25 Mar 2018 LESSON

BuddhaSasana-The

Home of Pali

in 29 Classical Galician- Clásico galego

Language

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kBfLtwy4H04

The 5th Tipitaka Chanting Ceremony, Bodhgaya, December 2009

Dhamma Dana

Published on Dec 17, 2009

This Video shows highlights of the 5th Tipitaka Chanting Ceremony at

Bodhgaya (Bihar, India) from 2nd to 12 th December 2009, organized by

the International Tipitaka Chanting Council, (PLEASE NOTE the next one

is scheduled from 2nd to 12th December 2010) http://www.tipitakachantingcouncil.or...

Acknowledgements to the Organizer of this great event and Imee Ooi for

the background Metta Chanting. Additional Clip by the Organiser of the

Ceremony can be viewed at this link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kKaZ1H…

Category

People & Blogs

This Video shows highlights of the 5th Tipitaka Chanting…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X2zUvfvYnxQ

INTERNATIONAL TIPITAKA CHANTING WATLAOINTER

Thong ma

Published on Dec 12, 2016

INTERNATIONAL TIPITAKA CHANTING WAT LAOBUDDHAGAYA INTERNATIONAL INDIA

Category

People & Blogs

INTERNATIONAL TIPITAKA CHANTING WAT LAOBUDDHAGAYA…

The

Home of Pali

U Razinda

Dept. of Ancient Indian & Asian Studies,

Nalanda, India

|

From:

“The Light of Majjhimadesa” - Volume (1), U Chandramani Foundation, 2001

Source:

http://www.rakhapura.com

Pali, in which only

the Buddha delivered his noble messages, appears to have been hallowed as

the text of the Buddhavacana. The language of the Buddhavacana is called

Pali or Magadhi and sometimes Suddha-Magadhi, presumably in order to

distinguish it from Ardha-Magadhi, the language of Jaina Canons. Magadhi

means the language or dialect current in the Magadha. In Pali Lexicon, the

definition of Pali is given thus: 1 pa paleti,

rakkhati ‘ ti pali. Since it preserves the Buddhavacana (words) in the

form of the sacred text, it is called Pali. In fact, the word Pali

signifies only “text” “sacred text”. 2

According to the tradition current in

Theravada Buddhist countries, Pali is Magadhi, Magadhanirutti,

Magadhikabhasa, that is to say, the language of the region in which

Buddhism had arisen. The Buddhistic tradition makes the further claim that

the Pali Tipitaka is composed in the language used by the Buddha himself.

3 For this reason Magadhi is also called Mulabhasa

4 as the basic language in which the words of the

Buddha were originally fixed. However, for Pali now arises the question,

which region of India was the home of that language which was the basis of

Pali.

Westergrd 5 and E.Kuhn

6 consider Pali to be the dialect of Ujjayini, because

it stands closest to the language of the Asokan-inscriptions of Girnar

(Guzerat), and also because the dialect of Ujjayini is said to have been

the mother-tongue of Mahinda who preached Buddhism in Ceylon (Sri Lanka).

R.O. Franke had a similar opinion by different means 7;

and he finally reached the conclusion that the original home of Pali was

“a territory, which could not have been too narrow, situated about the

region from the middle to the Western Vindhya ranges”. Thus it is not

improbable that Ujjayini was the centre of its region of expansion. Sten

Konow 8 too has decided in favour of the Vindhya region

as the home of Pali.

Oldenberg (1879) 9 and

E.Muller (1884) 10 consider the Kalinga country to be

the home of Pali. Oldenberg thinks that Buddhism, and with it’s the

Tipitaka, was introduced into Ceylon rather in course of an intercourse

between the island and the neighboring continent extending over a long

period. However, E.MUller bases his conclusion on the observation that the

oldest settlements in Ceylon could have been founded only by the people of

Kalinga, the area on the mainland opposite Ceylon and not by people from

Bengal and Bihar.

Maurice Winternitz 11

is of the opinion that Buddha himself spoke the dialect of his native

province Kosala (Oudh) and it was most likely in this same dialect that he

first began to proclaim his doctrine. Later on, however, he wandered and

taught in Magadha (Bihar) he probably preached in the dialect of this

province. When in course of time the doctrine spread over a large area,

the monks of various districts preached each in his own dialect. It is

probable that some monks coming from Brahmin circles also attempted to

translate the speeches of Buddha into Sanskrit verses. However, the Buddha

himself absolutely rejected it, and forbade learning his teachings in any

other languages except Magadhi. Here it is related 12,

how two Bhikkhus complained to the Master that the members of the order

were of various origins, and that they distorted the words of the Buddha

by their own dialect (Sakaya niruttiya). They, therefore, proposed that

the words of the Buddha should be translated into Sanskrit verses

(Chandaso). The Buddha, however, refused to grant the request and added:

Anujanamibhikkhave sakaya niruttiya buddhavacanam pariyapunitum. Rhys

Davids and Oldenberg 13 translate this passage by “I

allow you, oh brethren, to learn the words of the Buddha each in his own

dialect”. This interpretation, however, is not accorded with that of

Buddhaghosa, according to whom it has to be translated by “I ordain the

words of the Buddha to be learnt in his own language (i.e., in Magadhi,

the language used by Buddha himself)”. In fact, the explanation given by

Buddhaghosa is more acceptable, because neither the two monks nor Buddha

himself have thought of preaching in different dialects in different

cases.

Magahi or Magadhi 14 is

spoken in the districts of Patna, Gaya, Hazaribagh and also in the western

part of Palamau, parts of Monghyr and Bhagalpur. On its eastern frontier

Magahi meets Bengali. Dr.Grierson called the dialect of this region

Eastern Magahi (Magadhi). He (Dr.Grierson) has named western Magadhi

speeches as Bihari. In this time he includes three dialects, Magahi

(Magadhi), Maithili and Bhojpuri. Dr.Grierson, after a comparative study

of the grammars of the three dialects, had decided Maithili, Magahi and

Bhojpuri as three forms of a single speech. There are four reasons for

terming them as Bihari, viz.,

- Between Eastern Hindi and Bengali have

certain characteristics, which are common to the three dialects.

- It becomes a provincial language like

Gujarati, Punjabi, Marathi, etc.

- The name is appropriate from the

historical point of view. Bihar was so named after so many Buddhist

Viharas in the state. Ancient Bihar language was probably the language

of early Buddhists and Jainas.

- It is not a fact that in Bihar there is

no literature. In Maithili we have extant ancient literature.

Though Hindi is highly respected as a

literary language in Biharyetthe Maithili, Magahi and Bhojpuri languages

are deeply entrenched in the emotions of the people. The fact is that

Bihari is a speech distinct from Eastern Hindi and has to be classified

with Bengali, Oriya and Assamese as they share common descent from

Magadhi, Prakrit and Apabhransha. It is clear 15 that

an uneducated and illiterate Bihari when he goes to Bengal begins to speak

good Bengali with little effort but ordinarily it is not easy for an

educated Bihari to speak correct Hindi. Dr.Grierson has inclined to decide

that Magadhi was a dialect of Magadha (Bihar) and some parts of West

Bengal and Uttar Pradesh.

The area covered by the Buddha’s

missionary activities included Bihar and Uttar Pradesh including the Nepal

Tarai. So it may be assumed that the Buddha spoke in a dialect or dialects

current in those regions. Welhelm Geiger 16 considers

that Pali was indeed on pure Magadhi, but was yet a form of the popular

speech which was based on Magadhi and which was used by Buddha himself. It

may be imagined that the Buddha might choose a widespread language which

was used or understood by common people in the region, because through

which he could propagate his noble teachings to the common people. Thus,

Pali or the dialect of Magadha was more probably the language of the

common people and also a lingua franca of a large region including mainly

Magadha (Bihar).

References

(1). Dhamma Annual - Vol. 19, No. 10-11

(June-1995).

(2). Cf. the expression iti pi pali, eg., th 2 co. 618, where pali=patho.

Further, pali “sacred text” as distinct from attha katha, Dpvs.=20-20;

Mhvs.=33-100; Sdhs. (Saddhammasamgaha, ed. by Saddhananda); Jpts. (Journal

of the Pali Text Society) 1890, p. 535.

(3). Cf. Buddhaghosa: etha saka nirutti nama sammasambuddhena vuttappakaro

magadhiko voharo, Comm. to Cullavagga V 33-1. see samantapasadika, ed. by

Saya U Pye, IV416.(10)

(4). Sdhs. (Saddhammasamgaha, ed. by Saddhananda). Jpts. (Journal of the

Pali Text Society) 1890, pp.55(23), 56(21), 57(19).

(5). Uber dem altesten Zeitram der indischen Geschi chte, p. 87.

(6). Beitr., p. 6ff. Cf. Mur, original Sanskrit texts, II, p. 356.

(7). Pali and Sanskrit, p. 131 ff. By Pali I, of course, always understand

what has been called “Literary PAW’ by Franke.

(8). The home of Paiuaci, ZDMG (Zeitschrift der deutschen Morgenlandischen

Desell-schaft).

(9). The Vinaya Pitaka I, London 1879, p. L ff.

(10). Simplified Grammar of the Pali language, London 1884, p. III.

(11). History of Indian Literature, Vol. II, p. 13.

(12). Cullavagga V. 33 1=Vin. II, 139.

(13). Vinaya Texts III=Sacred Books of the East, XX, p.151.

(14). The Comprehensive History of Bihar, Vol. I, Part I, p. 91, edited by

Dr. Bindeshwari Prasad Sinha.

(15). Ibid. P. 89-90

(16). Pali Literature and Language, p. 6.

The Pali Language and Literature

From: Pali Text Society,

http://www.palitext.com/

Pali is the name given to the language of

the texts of Theravada Buddhism, although the commentarial tradition of

the Theravadins states that the language of the canon is Magadhi, the

language spoken by Gotama Buddha. The term Pali originally referred to a

canonical text or passage rather than to a language and its current use is

based on a misunderstanding which occurred several centuries ago. The

language of the Theravadin canon is a version of a dialect of Middle

Indo-Aryan, not Magadhi, created by the homogenisation of the dialects in

which the teachings of the Buddha were orally recorded and transmitted.

This became necessary as Buddhism was transmitted far beyond the area of

its origin and as the Buddhist monastic order codified his teachings.

The tradition recorded in the ancient

Sinhalese chronicles states that the Theravadin canon was written down in

the first century B.C.E. The language of the canon continued to be

influenced by commentators and grammarians and by the native languages of

the countries in which Theravada Buddhism became established over many

centuries. The oral transmission of the Pali canon continued for several

centuries after the death of the Buddha, even after the texts were first

preserved in writing. No single script was ever developed for the language

of the canon; scribes used the scripts of their native languages to

transcribe the texts. Although monasteries in South India are known to

have been important centres of Buddhist learning in the early part of this

millennium, no manuscripts from anywhere in India except Nepal have

survived. Almost all the manuscripts available to scholars since the PTS

(Pali Text Society) began can be dated to the 18th or 19th centuries C.E.

and the textual traditions of the different Buddhist countries represented

by these manuscripts show much evidence of interweaving. The pattern of

recitation and validation of texts by councils of monks has continued into

the 20th century.

The main division of the Pali canon as it

exists today is threefold, although the Pali commentarial tradition refers

to several different ways of classification. The three divisions are known

as pi.takas and the canon itself as the Tipitaka; the significance of the

term pitaka, literally “basket”, is not clear. The text of the canon is

divided, according to this system, into Vinaya (monastic rules), Suttas

(discourses) and Abhidhamma (analysis of the teaching). The PTS edition of

the Tipitaka contains fifty-six books (including indexes), and it cannot

therefore be considered to be a homogenous entity, comparable to the

Christian Bible or Muslim Koran. Although Buddhists refer to the Tipitaka

as Buddha-vacana, “the word of the Buddha”, there are texts within the

canon either attributed to specific monks or related to an event

post-dating the time of the Buddha or that can be shown to have been

composed after that time. The first four nikayas (collections) of the

Sutta-pitaka contain sermons in which the basic doctrines of the Buddha’s

teaching are expounded either briefly or in detail.

Buddhism: Language and Literature

Peter

Friedlander

Source: “Buddhist

Studies - Lecture Notes”, School of Social Sciences, La Trobe University,

Australia,

http://www.latrobe.edu.au/asianstudies/Buddha/index.html

Introduction

This is the last chapter on the

pre-Mahayana in this book. It covers a period from around the 6th century

BCE to the 2nd century CE. Within the scope of this chapter I will attempt

to simply sketch out various key aspects of Buddhist language and

literature over a period of eight centuries. This will be rather more an

investigation of the issues raised by the these topics than a detailed

study.

Language

Three key terms which we need to consider

are Sanskrit, Pali and Prakrit. We will also need to consider the terms

Magadhi and Ardha-Magadhi. What does Sanskrit mean? It has a root meaning

which does not actually refer to a language as such but to the concept of

something being refined or purified. The term Sanskrit can be found in

Buddhist texts used in the sense of meaning that which is refined as

opposed to that which is natural which is called Prakrit. Likewise in

Samkhya the principle of Prakriti is nature, hence Prakrit is

that which is natural. So in a sense then Sanskrit does not refer to a

language as such but to that which is refined or purified speech.

The languages in which the Vedas are

written are not quite the same as classical Sanskrit which was

standardised by Panini in about the 2nd century BCE. Despite the

variations in the linguistic forms from the Rig Veda, which is

considerably different from classical Sanskrit, the languages of the

majority of Indian high cultural texts are all in forms of Sanskrit. Some

of the later texts, such as the Puranas and the Epics are often not

in very refined Sanskrit, but they are still in Sanskrit. Also from around

the second century BCE onwards Buddhist texts began to be produced in

Sanskrit. These texts are often in a kind of Sanskrit mixed with

vernacular forms and which is often referred to as ‘Buddhist Hybrid

Sanskrit’. They are hybrid as they are a mix of Sanskrit and Prakrit. So

you should bear in mind that the term Sanskrit does not simply refer to

the classical standard form of the language but rather to a group of

related language forms which share a common heritage in grammar,

vocabulary and syntax.

In a similar manner the term Prakrit,

which means ‘natural [speech]’ refers to a group of language forms. Indeed

Prakrits appear in Sanskrit texts. For instance, classical Sanskrit

dramas, such as Kalidasa’s ‘Little clay cart’ include speeches by

different characters in various forms of Prakrit. For instance, whereas

the cook speaks in a ‘cook’s Prakrit’ and monkeys speak in a Prakrit

appropriate for monkeys, the king the leading characters and the narrator

speak in Sanskrit. This is similar to the modern linguistic situation in

India where within a single environment or location a variety of language

forms are spoken by different people. For instance in a monastery in Bodh

Gaya, the cooks and workers will speak in varieties of local dialect, but

the monks will speak in standard Hindi as well as their mother tongues,

and the leading figures will also be able to converse in English. In other

words the use of multiple languages according to social register is a

common feature in South Asia.

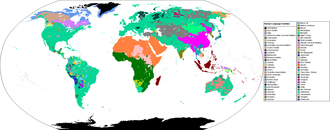

There are also three other elements which

need to be considered. First, there is the Dravidian element in the

language situation in India. This term refers to a completely different

language group nowadays spoken in the forms of Tamil, Malayalam, Telegu

and Kannada in the Southern states of India. There is also an isolated

pocket of the Dravidian languages in the Brahui language of modern

Pakistan. This language group is based on a quite distinct vocabulary and

grammar. Second, it should be noted, for completeness sake, that there are

also a variety of ‘tribal’ languages spoken in India which belong to

various other language groups again. These include the languages of the

tribal groups in Bihar, such as Santhali and Gond. Third there are also

languages from distinct language groups spoken in the Himalayan and

Burmese border regions of South Asia.

The situation at the time of the Buddha

was probably very similar with a wide variety of languages being spoken in

the area in which he lived. The dominant Prakrit language of his period in

the area where he was active was called Magadhi, as is the present Hindi

dialect of the area. This name is also preserved in the name given to the

Prakrit of many of the Jaina scriptures. These were compiled from oral

sources based on traditions active mainly in the Magadh area and the

language of these scriptures is called ‘Adha-Magadhi’, that is

‘Half-Magadhi’. It is a form of cleaned up Magadhi, half way between

everyday speech and a ‘pure’ language.

Language and meaning

The most important reason to consider any

of this is that we need to consider how the Buddha would have addressed

his audiences. He would have needed to speak in such a manner as would

have been comprehensible to his audience. Clearly is a situation of such

linguistic diversity he would have had to modulate his forms of speech

according to the audience he was addressing. Speaking to a king and to a

gang of street children, you need to speak in different ways.

Also we should consider that modern

mass-education and media have been rapidly erasing the differences between

dialects but that the situation in pre-modern cultures is one in which

language forms vary considerably over short distances. There is a Hindi

saying that after every three villages the language (that is the dialect)

changes. So in that the Buddha was born on the Nepali border then his own

language would not have been the same as that of Rajgir in Magadh or

Sarnath in Uttar Pradesh. There are elements in the texts of the Pali

canon which can be regarded as indicative of slight differences in

language perhaps reflective of these ancient dialect differences.

Surely when the Buddha was addressing King

Bimbasara he would have expressed himself in a different register than

when he was addressing an ascetic who was visiting from another part of

India, such as Bahiya who had come from Maharashtra to visit the Buddha. I

would speculate that a skilled orator would express even the same notion

to both audiences in different ways in order to get the teaching across as

well as possible. If then you had been listening to both speeches you

would have heard two versions of the same teaching. Were you then to be

asked ‘which was the genuine teaching of the two’ you would have had to

say that both were genuine, although they were different in exact wording

as they carried the same teaching.

The question of how to teach and the

languages in which to teach is indeed addressed in the Pali canon. It is

said that the Buddha was asked when teaching in different areas should the

teachings be in a single language or adapted to the local language. The

Buddha said that the teachings should be made in the language of the area.

So disciples of the Buddha would have been teaching in a variety of

languages according to the contexts in which they found themselves, so

that people could understand them.

The Buddha is also said to have favoured

natural language, Prakrit, over refined speech, Sanskrit, as the latter

would not have been comprehensible to the general public. So what then is

the relationship between Prakrit and Pali?

In a sense the term Pali, like Sanskrit,

does not refer to a language at all. Richard Gombrich pointed out that it

actually means ‘sacred scripture’ and is a descriptive term for the

Theravada scriptures and the language they are in. It is a standardised

and consistent language based on earlier dialects. It is not exactly what

the Buddha said, it is a standardised form of what the Buddha said. It is

close to the Prakrit Magadhi languages that the Buddha probably spoke in,

but it is not identical to them.

The Pali canon features long set phrases

which are repeated countless times in identical terms. Such as the

formulation of the Noble Truths and set descriptions like ‘he saluted the

Buddha and sat down at one side of him’. These set doctrinal phrases and

stock descriptive elements are, however, normally contextualised within

passages which are each in a sense unique.

It seems to therefore be appropriate to

point out that we have no way of knowing when the tradition of explaining

the Pali canon with further commentorial material began. The textual

traditions now extant always feature the main texts and subsidiary

commentaries. It is known than that this tradition goes back in Sri Lanka

to the time of the introduction of Buddhism, when it is said that

commentaries explaining the texts were introduced along with the texts

themselves. (I am using the term text here to refer to a spoken text, not

a written text). This pattern of text and commentary is common in South

Asian literature. It is also a feature of non-Buddhist Indian literature

and a Sutra (Skt) or Sutta (Pali) means a ‘string’ or

‘thread’ and is the condensed essence of a text onto which a commentary

should be stung.

The repetition of set phrases and material

to contextualise and explain them is a feature which is typical of texts

with commentaries. Part of the motivation for this is clearly that it is

no good giving a teaching in a language nobody understands, it has to be

accessible. Likewise even if the main teaching is linguistically

comprehensible it will probably need an explanation to contextualise and

make the meaning clear to the particular audience which is being

addressed. Thus the issue of what constitutes ‘the speech of the Buddha’ (Buddhavacana)

is further complicated here by the possibility that we may have multiple

versions of reported versions of what the Buddha said, all genuine, but

all slightly different.

There is also an issue which is raised by

a reference in the canon to two Brahmin brothers who had become monks and

remembered the teachings and asked for permission to chant them in the

manner of a Vedic chant. But the Buddha said that this was not

appropriate. Despite this the Buddhist texts are chanted, but the manner

and styles of their chanting do not conform to the Vedic patterns for the

chanting of texts.

If we entertain the notion that the Pali

texts are not the actual speech of the Buddha, but standardised versions

of what he said, what then would be the relationship of the Sanskrit

versions of the texts to the Pali versions? The Sanskrit versions are also

standardised versions and would stand in similar relationship to the

original utterances.

If we put aside the Theravada claim that

the Pali texts are literal word of the Buddha then we have to consider

this possibility. The existence of other Prakrit versions also seems to

point to the same truth. None of the extant versions are simply ‘the

literal words’ of the Buddha, all textual traditions are, in one way or

another, standardised versions of the words of the Buddha. The canon

itself contains references to how it is important to understand the

intended meaning of the text and not get caught up in the literal meaning.

In the present day the various Sanskrit

and Prakrit versions of the canon are not all perfectly preserved. There

are large sections of the canons of a number of Nikaya Buddhist

traditions extant in their original language forms and, fortunately, more

extensive translations of these texts into Chinese. Therefore it is

possible to compare the Sanskrit, Prakit and Pali versions of some texts.

An instance of this is the Dhammapada.

This is available in Pali, Sanskrit, two Prakrits, Chinese and Tibetan

translations. The various traditions do not have exactly the same text.

The number of verses vary, the order of the verses vary and the texts of

the verses vary and to some extent even the meaning of individual verses

vary.

The common endeavour behind all of this

was clearly a constant effort by different people in diverse locations to

keep the Buddha’s teachings comprehensible. For some people it seemed that

Pali was the best, for some Prakrits, for some a widely know standard

language, Sanskrit, seemed the most appropriate. For some it was necessary

to translate the texts into totally new languages, such as Chinese. In the

article by (I have forgotten his name) on the translation of the Lotus

Sutra into Chinese there is a fine description of this translation

process. It needed one or more Indian Pandits and one or more central

Asian and Chinese Pandits who would sit together. The India Pandit reads

out the text to the Chinese Pandit who writes it down and then it is

compared for meaning by the various people involved. In the particular

case that was being studied in this article it is argued that although the

text is described as being in Sanskrit, the Indian Pandit was apparently

reading it out in Prakrit based on the evidence of the kinds of mistakes

that were being made in translation. So this suggests that not only do we

need to consider the languages of the written forms of the texts but of

the spoken forms of exposition which were employed. We must remember then

that the text consists of the text, the expounder and the listener.

Linguistic change and the Growth of

Buddhism

One other point about the linguistic

changes in the growth of the canon. It seems to reflect to some extent the

geographical spread of Buddhism. By the second century CE Buddhism had

spread throughout South Asia and into Central Asia and China. Therefore

the issue of how to give the teachings must have been of prime concern in

the Buddhist world. The common consensus was clearly that the texts needed

to be translated into languages appropriate for the peoples of the areas

in which Buddhism was active. But at the same time there is of course the

overarching need to maintain the meaning of the teachings while the form

of expression varies. Within the North Indian linguistic area is was

possible to maintain key terms in forms which were commonly employed,

sukha, dukkha, dharma, karma, nirvana, samsara, etc.

But, once the texts started being

translated into Chinese a new set of problems was apparent. Just as terms

such as dharma, nirvana, samsara present problems for translation

into English, so to is there a problem when translating such terms into

Chinese. There was, for instance, no common view of reincarnation

samsara as a given truth in Chinese.

Interestingly enough the first school of

Chinese translation, the old school, translated by finding the most

similar Chinese terms available for Indic terms, normally finding terms

from Taoism that were equivalent. Thus the Buddha became a teacher of the

Tao rather than the dharma. This translation approach was standard

from the beginnings in the 1st/2nd century CE up to around the 5th

century. At this point the translators revised their views and

retranslated the texts again using Chinese equivalent versions of the

Indic terms rather than Taoist equivalents.

Buddhist literature

So was the canon of the Nikaya Buddhist

traditions exactly the same for all the traditions? I have indicated above

that in the case of the Dhammapada there were variations between

the different traditions. Variations in the number of verses and verses

that are common to all traditions and unique to individual traditions. You

cannot simply say that one version is the original version, yet it is

desirable to consider how the versions related to each other. It is likely

that non of the extant versions are the original version as oral

traditions are often more fluid than textual traditions. So rather than

saying that any one textual version it might be better to propose that all

the versions are but windows onto an earlier oral tradition. There are in

the case of other texts instances where the Pali versions of texts seem

more developed than other versions. For instance the Pali

Mahaparinibbana sutta seems more complex than the version translated

into Chinese from the Sanskrit Sarvastivada tradition. The latter having a

more simple description of the funeral rites and the former a more

elaborate version.

Nikaya literature: vinaya, sutta,

and abhidharma pitakas

There are basically three parts of the

Nikaya Buddhist canon. The Sutta pitaka, the Vinaya pitaka

and the Abhidhamma pitaka. The Sutta pitaka is fairly

consistent in some parts over the various versions, in particular the

Digha and Majjima, Anguttara and Samyakta Nikayas are

fairly consistent in their contents, if not in the exact forms of the

texts.

However the next Nikaya,

Khuddaka Nikaya which in the Pali version contains 14 texts has a much

greater variation in its contents. It includes the Khuddaka Pattha,

a sort of early version of a collection of the chants for daily recitation

and the Dhammapada, which I have already noted has considerable

variations between the various versions. The next text is the Udana,

which at least in the Sarva stiva da version is similar to the name given

to the Dhammapada which is called the Udanavarga. There is

also the Itivuttika further sayings of the Buddha and the jatakas.

The number of the jatakas also varies from tradition to tradition.

There are also instances of completely different works being included in

this part of the canon by different traditions.

The Sarvastivada tradition included a text

called the Mahavastu in the canon, a kind of life of the Buddha,

but the Theravada tradition does not include this text. While the

Theravada tradition included the Vimanavattu and the

Pettavatu in its canon, tales on the good and bad results of giving or

not giving to the samgha. These last two texts are regarded as very

late by scholars. So to are the following texts called the Buddhavamsa,

an account of the previous 24 Buddhas and the Cariya-pitaka which

is an account of how the Buddha manifested the ten perfections in his

previous lives as a Bodhisattva. The very fact that the title of the last

includes the term pitaka in its title, which is a term that means

basket or winnowing fan suggest that it must have come from a time when

the canon could be put into baskets, clearly only possible once it had

been written down.

The Pali canon was first written down in

the first century BCE in Sri Lanka according to Sri Lankan sources. The

traditional explanation of this is that it was due to fear of parts of the

canon getting lost that led to it being written down. It is said that

during a famine there was only a only a single monk left alive who knew

one section of it and this was the cause of it being set down in writing.

You may think it was odd that it was not previously written down, but

there seems to have been a reluctance to write things down in ancient

India.

To return to the contents of the canon the

next part is the Vinaya pitaka which includes details on how the

monks and nuns should live and stories to explain the rules of the

monastic code. Even in the fifth century CE when Chinese pilgrims were

visiting India and trying to get copies of the Vinaya they found it

quite difficult as in many places it existed only in the form of oral

tradition. The reluctance to commit to writing parts of the canon seems to

have been a long standing aspect of the tradition in India. People simply

preferred to remember the whole thing. It was indeed one specialisation

that monks could have was to memorise entire parts of the canon, and

memorisation of the Vinaya pitaka was apparently a common

phenomena.

The last part of the canon is the

Abhidhamma pitaka, a philosophical study of the Buddha’s teachings.

This contains seven works in the Theravada version. In the Sarva stiva da

version the number and nature of the works was somewhat different. Certain

parts show evidences of having been based on similar earlier traditions,

others are clearly distinctive contributions of the various schools. It is

not clear if all schools had their own Abhidhamma pitaka traditions

or they were shared in common by various traditions. The main

Abhidhamma pitaka traditions seem to have been those of the Theravada

and the Sarva stiva da traditions.

The different Abhidhamma pitaka

traditions are acknowledged to be later parts of the canon which were not

in existence at the time of the first council and they post date the

Sutta and Vinaya pitakas. There are considerable variations

between the different philosophical traditions. The Theravada tradition

held that there were only four realities rupa, citta, cetasaka and

Nibbana, whereas the Sarva stiva da tradition held that

there were five realities and included space a ka sa as a fifth

reality. Also whilst the Theravada tradition held that only the present

moment ‘existed’ when things were perceived, the Sarva stiva da

tradition held that things ‘existed’ in the past, present and future. This

last view accounts for the name of the tradition which means ‘all exists’.

Due to this it is natural that the philosophical texts vary in their

contents. Despite sharing a common interest in philosophical analysis.

Indeed the differences between the traditions form the basis for a

Theravada tradition text, the Katthavattu or ‘Points of

controversy’ which outlines the differences between the traditions as seen

from a Theravada viewpoint.

A point of note in this is that in the

Katthavattu the philosophical position on the possibility of

transferring merit to deceased relatives of the Theravada tradition is put

as that it is impossible in distinction from that of the other schools

which say that it is possible. But, this viewpoint also conflicts with the

views expressed in the Khuddaka Nikaya of the Theravada

canon itself, in which the transfer of merit is clearly regarded as

possible. A further twist to this issue is that in the later text called

Milanda Panha a compromise is suggested that merit can be

transferred to some classes of preta, and this is the current view

of most Theravada tradition followers.

Nikaya and Mahayana literature

There is a further question which is worth

addressing here is. ‘What parts of the Nikaya Buddhist canon are

also accepted by Mahayana Buddhist traditions?’ Interestingly enough

though the question becomes not really what are accepted texts, so much as

what are texts that interest different traditions. The Sutta texts

for instance are accepted as genuine by the Mahayana tradition, but they

are of little interest to the Mahayana it seems. However, almost all the

traditions agree on the importance of the Dhammapada as the essence

of the Buddha’s teachings.

The Vinaya pitaka is also a

commonly held part of the early canon. Although that majority of East

Asian and Himalayan traditions follow the Sarva stiva da Vinaya

rather than the Theravada Vinaya, however there are in theory no

major differences. This is of course quite separate from the question of

how the Vinaya is interpreted which evidently varies widely between

the Northern and Southern traditions.

The Abhidhamma contains almost no

texts which are common between Nikaya Buddhists, let alone between

the Nikaya Buddhists and the Mahayana Buddhists. However, there is

a similar fascination with philosophy in all the traditions.

It is also vital to realise that there is

much in Theravada tradition which is unique to it and not held in common

with other Nikaya Buddhist traditions. The great synthesis of

teachings in the Visuddhimagga, ‘The Path of Purification’ by

Buddhaghosa which was composed in the 5th century CE is distinctly

Theravada in its viewpoint. It was based on a translation into Pali

of the existing Singhalese commentaries on the canon and records

traditions which may well go back in origin to India but had undergone

centuries of evolution in Sri Lanka. Buddhaghosa himself was from North

India, from near Bodh Gaya and went to Sri Lanka to translate their

vernacular commentaries into Pali.

The famous Sri Lankan chronicles, such as

the Mahavamsa are also distinctly Sri Lankan Theravada creations

that link the history of Buddhism to that of the ruling dynasties of Sri

Lanka.

There was also a continuous tradition of

creating new Pali texts in South East Asia, in Burma, Thailand, Cambodia

and Laos. It is interesting to note that in this case the argument for

Pali as the sacred language has completely altered. The early argument for

Pali it seems was, as suggested above, that it was comprehensible to the

people as it was close to everyday speech. Evidently in Sri Lanka and

South East Asia this was not the case. Rather it was seen as being the

authentic language of the Buddha. In a sense then it has become a kind of

purified language whose function is akin to that of Sanskrit in India, a

kind of sacred lingua franca comprehensible over a wide area and

felt to be the essence of refinement and imbued with great power and

sophistication.

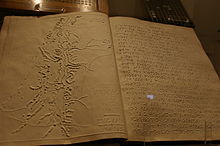

The Earliest Buddhist Manuscripts

Finally, as an epilogue let us consider

the case of the earliest Buddhist manuscripts yet discovered. A few years

ago the British Library in London was approached to find out if it was

interested in acquiring what appeared to be some old manuscripts which had

emerged from war torn Afghanistan. These were a collection of rolled up

birch bark manuscripts. These are very difficult materials to deal with as

they normally crumble into dust as you touch them. In this case they were

stored in urns and they were purchased in the urns. The library spent a

year and a half gradually humidifying and unrolling the manuscripts a

millimetre at a time and ended up with fragile sheets of birch bark

sandwiched between perspex sheets. It should be born in mind that birch

bark is a bit like vellum, as long as its kept in normal conditions it is

pliable and an excellent writing surface, it only become so crumbly if

left to dry out in an arid environment for two thousand years. These were

then photographed and digitised. They are a very exciting discovery as it

has become apparent that they date from around the first century CE. They

are written in a dialect of Prakrit in a script called Kharoshti,

and the number of scholars it is said who can read this script are said to

be merely a handful. The Kharoshti script was popular in the North

Western part of India and dropped out of use by the time of the Islamic

invasions of India. The group of scholars who are working on these

manuscripts are still working on deciphering them.

The initial reports indicate that they are

all fragments of works. This turns out to be because they are fragments of

old manuscripts which had been re-copied and the old manuscripts were

interred in an urn and buried as if they the body of the Buddha. This in

itself is fascinating as it shows that the Buddhists buried their old

manuscripts, Hindu’s also treat their manuscripts like their dead and

prefer to ideally place them into rivers as they do the ashes of bodies.

The contents of the manuscripts include

sections from Dhammapada, the rhinoceros verses, and verses in

praise of the lake now known as Manasarover by Mount Kailash, known in

Buddhist literature as lake Anavatapta. There also indications that they

productions of the Dhammaguptika tradition. They contain no parts of the

Vinaya or Abhidhamma pitakas and appear to be all drawn from

the Sutta pitaka. However, we are still waiting for further

detailed reports on their contents.

Conclusion

In conclusion then it is clear that the

breadth and depth of Buddhist literature is hard to comprehend. Even were

you to become a master of the Theravada Tipitaka you would still

not have read the greater part of the literature of the other Nikaya

Buddhist traditions. Also to be able to do a good comparative study of

this literature in real depth you would need to know not just Pali,

Prakrit and Sanskrit, but also to access the translations of the parts of

the Nikaya Buddhist canons lost in Indic languages you need to

learn Chinese to read these portions in translation. This is as they say

in Australia ‘a big ask’, however, beginning to map out the dimensions of

this issue is the first step on the road to the study of Nikaya

Buddhist literature.

The Pali Language

Source:

http://www.buddhamind.info

A question often asked is: “Did the

Buddha speak Pali?” If so, how much of the original language has been

retained? If not, how much has translation affected the accurate

transmission of the teachings? There seems to be no one answer to these

questions but I offer the following as the results of my investigation.

The paramount power in India for two

centuries, spanning both before and after the Buddha, was the Kingdom of

Kosala, of which the Buddha’s birth kingdom, Magadha, was a fiefdom.

Magadhi seems to be a dialect of Kosalan, and there is some evidence that

this was the language that the Buddha spoke. The Pali of the Canon seems

to be based on the standard Kosalan as spoken in the 6th and 7th centuries

BC. The script used on the rock edicts of Asoka is a younger form of this

standard. On one of the Asoka pillars (about 300 BC) there is a list of

named Suttas which can be linguistically placed within the Singhalese

Canon.

Sanskrit was also widely spoken and

warrants discussion. It seems to have been the language of the Brahmin’s,

the ’spiritual’ class. It is etymologically older than Pali but, as

regards texts and inscriptions, the native tongue (Kosalan) was the more

common or popular medium. In the Text we see the Buddha encouraging his

disciples to teach in the popular language of any area. However after the

Buddha’s death, what were considered more ‘learned’ forms were gradually

made use of, despite the fact that these gave a less faithful picture of

the living speech. Slowly the efforts to represent the real facts of the

spoken language gave way to another effort, the expression of learned

phraseology, until roughly 300 AD, classical Sanskrit became used

exclusively in relation to Buddhism. This trend is reflected in the

scripture of later Buddhist traditions.

The use of Pali is practically confined to

Buddhist subjects, and then only in the Theravada school. It’s exact

origin is the subject of much learned debate and from the point of view of

the non-specialist, we can think of it as a kind of simplified, common

man’s Sanskrit. The source of the Pali Text we have lies in the North of

India. It is definitely not Singhalese in origin as it contains no mention

of any place in Sri Lanka, or even South India. The similes abounding in

the Singhalese literature are those of a sub-tropical climate and of a

great river valley rather than those of a tropical island.

Being an essentially oral language,

lacking a strong literary base of its own, it adopted the written script

of each country it settled in. It is clear that by the time the Text

arrived in Sri Lanka, with Asoka’s son Mahinda, about 240 BC, it was

considered closed.

Conclusion:

Any historical study is much like a jigsaw

puzzle. Piecing together information from a scrap of parchment here, a

clay tablet there; comparing various bits of antiquity, the opinions and

insights of others; analysing and evaluating - and then - coming to a

conclusion. The more Buddhist history books I studied, to try and

determine precise information, the more opinions I ended up collecting.

History, it seems, can be very much a matter of opinion.

Very few undisputed facts exist by which

to prove the authenticity of the Pali Canon. Even the dates of the Buddha

are questionable. The earliest reliable dates in Indian history that we

have are those for Emperor Asoka’s rule; 274 - 236 BC. We can also be

relatively certain that the Text remained unchanged from the time it was

written down, about 80 BC.

As regards the reliability of the Text I

felt two items to be of greatest importance.

* Firstly: The reason that anything

survives the rigours of more than 2000 years of history is that it is

considered to be of great value. Presumably the reason for this evaluation

was that the teaching was seen to work, i.e. to lead to the transcendence

of suffering. Such a known treasure would have been well guarded and part

of this protection would have been a tremendous concern for retaining the

‘jewel’ in its entirety, i.e. accurately.

* Secondly: After several centuries of

travelling to many different lands and being translated into different

languages, the disparity between the various renderings of the main Text

existing today in Pali, Sanskrit, Chinese and Tibetan is typically

greatest in matters of least importance. Only very rarely are differences

founded on doctrinal matters. It can be seen that these works are clearly

not independent compositions, being very similar in their substantive

content. This “authenticity by comparison” is an important item in support

of scriptural accuracy. More specifically, the Vinaya is almost without

exception, identical in every Buddhist tradition.

On a more general note:

I feel that the majority of us who have

come to give the Text some consideration, originally set out in search of

a guide by which to find a way to resolve the root-problem of our personal

existence. The process of production warrants investigation but surely the

true test of any guide book is its ability to lead one to the desired

destination. The whole energy behind the Buddha’s teaching was the ending

of suffering. If what you glean from the Text eases or ends your suffering

then the teaching has been accurately transmitted. What is of greatest

importance is to take the teachings that seem relevant, that feel

applicable to your life, and to make them a personal reality, to turn the

theory into practice.

-ooOoo-

|

Source: Internet

[Back

to English Index]

last updated: 07-07-2005

29 Classical Galician

29 Clásico galego

2570 Sáb 24 de marzo de 2018 LECCIÓN

http://www.buddha-vacana.org/

Buda Vacana

- As palabras do Buda -

O budismo clásico (ensinanzas do espertado con conciencia) pertence ao mundo e todos teñen dereitos exclusivos:

é a enerxía máis positiva do sitio informativo e orientado á

investigación, que propaga as ensinanzas do Despertar con consciencia do

Buda e do Movemento de Techno-Politico-Socio Transformación e

Emancipación Económica seguido por millóns de persoas en todo o mundo.

Realizando

a tradución exacta como unha lección desta universidade na súa lingua

materna a esta tradución de Google https://translate.google.com ea súa

propagación dá dereito a converterse nun Enterreiro de Rede (Sottapanna)

e conseguir a Felicidade Eterna como Obxectivo Final. Analytic Insight-Net - FREE Online Analytical Insight-Net Tipiṭaka

Research & Practice Universidade e relacionadas NOTICIAS a través de

http://sarvajan.ambedkar.org en 105 LINGUAS CLÁSICAS

Buda Vacana

- As palabras do Buda -

Aprende Pali en liña de xeito gratuíto e sinxelo.

Este

sitio web está dedicado a aqueles que desexan comprender mellor as

palabras do Buda aprendendo os conceptos básicos da lingua Pali, pero

que non teñen moito tempo dispoñible para iso. A

idea é que se o seu propósito é simplemente habilitarse para ler os

textos de Pali e ter unha sensación xusta de comprendelos, aínda que esa

comprensión non abarque todos os detalles mínimos das regras

gramaticais, realmente non precisan gastar moito o tempo loitando cunha aprendizaxe desalentadora da tediosa teoría gramatical que inclúe moitas declinacións e conxugacións.

Nese

caso, basta limitarse a simplemente aprender o significado das palabras

Pali máis importantes, porque a repetida experiencia da lectura

proporciona unha comprensión empírica e intuitiva das estruturas de

oracións máis comúns. Así, poden facerse autodidactas, elixindo o tempo, a duración, a frecuencia, os contidos e a profundidade do seu propio estudo.

A

súa comprensión da Buda Vacana farase moito máis precisa xa que

aprenden e memorizan sen esforzo as palabras e as fórmulas importantes

que son fundamentais no ensino de Buda, por medio da lectura regular. A súa aprendizaxe ea inspiración a partir diso vanse a medrar a medida

que mellorará a súa receptividade ás mensaxes do profesor.

Exención de responsabilidade: Este sitio web é creado por un autodidacto e está feito para autodidactos. O

webmaster non seguiu ningún curso oficial de Pali e non hai ningún

reclamo de que toda a información aquí presentada estea totalmente libre

de erros. Os que desexan unha precisión académica poden considerar unirse a un curso formal de Pali. No caso de que os lectores noten algún erro, o webmaster agradece se o

informan a través da caixa de correo mencionada en “Contacto”.

Sutta Piṭaka -Digha Nikāya

DN 9 -

Poṭṭhapāda Sutta

{extracto}

- As cuestións de Poṭṭhapāda -

Poṭṭhapāda fai preguntas sobre a natureza de Saññā.

Nota: textos simples

http://www.buddha-vacana.org/suttapitaka.html

Sutta Piṭaka

- A cesta de discursos -

[sutta: discurso]

O Sutta Piṭaka contén a esencia do ensino de Buda sobre o Dhamma. Contén máis de dez mil suttas. Está dividido en cinco coleccións chamadas Nikāyas.

Dīgha Nikāya

[dīgha: long] O Dīgha Nikāya reúne 34 dos discursos máis longos que deu o Buda. Hai varias indicacións de que moitas delas son adicións tardías ao corpus orixinal e de autenticidade cuestionable.

Majjhima Nikāya

[majjhima: medio] O Majjhima Nikāya reúne 152 discursos do Buda de lonxitude intermedia, tratando diversos asuntos.

Saṃyutta Nikāya

[samyutta: grupo] O Saṃyutta Nikāya reúne as suttas segundo o seu tema en 56 subgrupos chamados saṃyuttas. Contén máis de tres mil discursos de lonxitude variable, pero xeralmente relativamente curto.

Aṅguttara Nikāya

[aṅg: factor | uttara:

additionnal] O Aṅguttara Nikāya está subdividido en once subgrupos

chamados nipātas, cada un dos cales agrupa discursos compostos por

enumeracións dun factor adicional versus as do precedente nipāta. Contén miles de suttas que xeralmente son curtos.

Khuddaka Nikāya

[khuddha:

curto, pequeno] Os textos curtos de Khuddhaka Nikāya e considerado

composto por dúas estratos: Dhammapada, Udāna, Itivuttaka, Sutta Nipāta,

Theragāthā-Therīgāthā e Jātaka forman os estratos antigos, mentres que

outros libros son complementos tardíos ea súa autenticidade é máis cuestionable.

http://www.buddha-vacana.org/formulae.html

Árbore

Fórmulas de Pali

A

visión sobre a que se basea este traballo é que as pasaxes das suttas

que son as máis repetidas polo Buda en todos os catro Nikāyas pódense

tomar como indicando o que el consideraba máis digno de interese no seu

ensino , e ao mesmo tempo que o que representa con máis precisión as palabras reais. Oito deles expóñense no Gaṇaka-Moggallāna Sutta (MN 107) e describen como Sekha Paṭipadā ou P

http://www.buddha-vacana.org/formulae.html

Fórmulas de Pali

A

visión sobre a que se basea este traballo é que as pasaxes das suttas

que son as máis repetidas polo Buda en todos os catro Nikāyas pódense

tomar como indicando o que el consideraba máis digno de interese no seu

ensino , e ao mesmo tempo que o que representa con máis precisión as palabras reais. Oito deles expóñense no Gaṇaka-Moggallāna Sutta (MN 107) e descríbense

como Sekha Paṭipadā ou Path para un baixo o adestramento, que

prácticamente lidera o neófito ata o cuarto jhāna.

Sekha Paṭipadā - O camiño para un de adestramento

Doce fórmulas que definen paso a paso as principais prácticas prescritas polo Buda. É fundamental para quen quere avanzar con éxito, xa que contén as

instrucións que permitirá que o meditador configure as condicións

indispensables para unha práctica eficiente.

Ānāpānassati - Conciencia da respiración

A práctica do ānāpānassati é moi recomendable polo Buda para todo tipo

de propósitos saudables e aquí podes entender con precisión as

instrucións que dá.

Anussati - As Recolecciones

Aquí temos a descrición estándar do Buda (≈ 140 oc.), O Dhamma (≈90 occ.) Ea Sangha (≈45 oc.).

Appamāṇā Cetovimutti - As liberacións sen límites da mente

O Buda a miúdo eloa a práctica dos catro appamāṇā cetovimutti, que son

coñecidos por traer protección contra os perigos e por ser un camiño

que conduce a Brahmaloka.

Arahatta - Arahantship

Esta é a fórmula de inventario pola que se descrebe a realización da arandería nas suttas.

Ariya Sīlakkhandha - O agregado nobre da virtude

Varias regras a seguir por bhikkhus.

Arūpajjhānā - The Formless Jhānas

Aquí están as fórmulas de accións que describen as absorcións de

samādhi máis aló do cuarto jhāna, que son referidas na literatura tardía

de Pali como arūpajjhānas.

Āsavānaṃ Khayañāṇa - Coñecemento da destrución dos āsavas

Coñecemento da destrución dos āsavas: arahantship.

Bhojane Mattaññutā - Moderación nos alimentos

Moderación nos alimentos: coñecer a cantidade adecuada para comer.

Cattāro Jhānā - Os catro jhānas

As catro jhānas: ter un agradable cumprimento.

Indriyesu Guttadvāratā - Vixilancia á entrada das facultades sensoriais

Garda na entrada das facultades de sentido: restricción sen sentido.

Jāgariyaṃ Anuyoga - Dedicación á vixilia

Dedicación á vixilia: día e noite.

Kammassakomhi: son o meu propio kamma

Esta fórmula explica un dos fundamentos do ensino do Buda: unha versión subjetiva da lei da causa e do efecto.

Nīvaraṇānaṃ Pahāna - eliminación de obstáculos

Eliminación dos obstáculos: superación da obstrución dos estados mentais.

Pumajjā - A saída

A saída: como se decide renunciar ao mundo.

Pubbenivāsānussatiñāṇa - Coñecemento do recordo dos antigos lugares de vida

Coñecemento do recordo dos antigos lugares de vida: recordando as vidas pasadas.

Satipaṭṭhāna - Presenza de conciencia

Estas son as fórmulas coas que o Buda define en breve cal son as catro satipaṭṭhānas (≈33 oc.).

Satisampajañña - Comprensión e comprensión

Mindfulness e comprensión completa: unha práctica ininterrompida.

Satta saddhammā - Sete boas calidades

Sete calidades fundamentais que deben ser dominadas polo alumno para ter éxito. Catro destas calidades aparecen tamén entre as cinco indriyas espirituais e as cinco balas.

Sattānaṃ Cutūpapātañāṇa - Coñecemento do renacemento dos seres doados

Coñecemento do renacemento dos seres doados.

Sīlasampatti - Realización en virtude

Realización en virtude: unha observación atenta das regras de Pātimokkha.

Vivitta Senāsanena Bhajana - Recorrendo a vivendas illadas

A elección dun lugar axeitado e a adopción da boa postura física e mental é outra condición sine qua non de práctica exitosa.

Folla Bodhi

http://www.buddha-vacana.org/patimokkha.html

Pātimokkha

- As pautas de Bhikkhu -

Estas son as 227 pautas que cada bhikkhu debe aprender de memoria na linguaxe Pali para poder recitarlas. Aquí ofrecerás (esperemos) unha análise semántico de cada guía.

Pārājika 1

Se

algún bhikkhu participase no adestramento e no sustento dos bhikkhus,

sen renunciar á formación, sen declarar a súa debilidade, se involucrar

na relación sexual, ata con un animal feminino, é vencido e xa non está

afiliado.

http://www.buddha-vacana.org/patimokkha/par1.html

">Pārājika 1

yo pana bhikkhu bhikkhūnaṃ sikkhā · s · ājīva · samāpanno sikkhaṃ a ·

paccakkhāya du · b · balyaṃ an · āvi · katvā methunaṃ dhammaṃ

paṭiseveyya antamaso tiracchāna · gatāya · pi, pārājiko hoti a saṃvāso.

Se algún bhikkhu participase no adestramento e no sustento dos

bhikkhus, sen renunciar á formación, sen declarar a súa debilidade, se

involucrar na relación sexual, ata con un animal feminino, é vencido e

xa non está afiliado.

Eu pana bhikkhu Debería algún bhikkhu

bhikkhūnaṃ sikkhā · s · ājīva · samāpanno participando na formación e no sustento dos bhikkhus,

sikkhaṃ a · paccakkhāya sen renunciar á formación,

du · b · balyaṃ an · āvi · katvā sen declarar a súa debilidade

Methunaṃ dhammaṃ paṭiseveyya participa das relacións sexuais,

antamaso tiracchâna · gatāya · pi, mesmo cun animal feminino,

pārājiko hoti a · saṃvāso. el é derrotado e xa non está afiliado.

http://www.buddha-vacana.org/download.html

Descarga do sitio web

Descarga o sitio web (versión de Januray 2013):

Pulse AQUÍ

http://www.buddha-vacana.org/contact.html

Árbore

Contacto

Para calquera comentario, suxestión, pregunta:

Non dubide en informar calquera erro, discrepancia, ligazón rota, información baleira · burbulla, etc pode atoparse. O webmaster estará agradecido.

Fácil acceso:

Dīgha Nikāya

Majjhima Nikāya

Saṃyutta Nikāya

Aṅguttara Nikāya

http://www.buddha-vacana.org/sutta/digha.html

Árbore

Dīgha Nikāya

- Os longos discursos -

[dīgha: longo]

O Dīgha Nikāya reúne 34 dos discursos máis longos supuestamente entregados polo Buda.

Poṭṭhapāda Sutta (DN 9) {extracto} - tradución mellorada

Poṭṭhapāda fai preguntas sobre a natureza de Saññā.

Mahāparinibbāna Sutta (DN 16) (extractos) - palabra por palabra

Este sutta recolle diversas instrucións que o Buda deu por mor dos

seus seguidores despois do seu falecemento, o que fai que sexa un

conxunto de instrucións moi importante para nós hoxe en día.

Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Sutta (DN 22) - palabra por palabra

Este sutta é ampliamente considerado como unha referencia fundamental para a práctica da meditación.

—— oooOooo ——

http://www.buddha-vacana.org/sutta/majjhima.html

">Majjhima Nikāya

- Os discursos de lonxitude media -

[majjhima: medio]

O Majjhima Nikāya reúne 152 discursos do Buda de lonxitude intermedia, tratando de diversas materias.

Sabbāsava Sutta (MN 2) - tradución mellorada

Moi interesante sutta, onde se desvían as distintas formas nas que os āsavas, fermentadores defilementos da mente.

Bhayabherava Sutta (MN 4) - tradución mellorada

¿Que tería que vivir na soidade no deserto, completamente libre de medo? O Buda explica.

Vattha Sutta (MN 7) {extracto} - tradución mellorada

Atopamos aquí unha lista bastante estándar de dezaseis defilements

(upakkilesa) da mente, e unha explicación dun mecanismo polo que se

obteñen estas “confidencias confirmadas” no Buda, o Dhamma e a Sangha

que son factores de entrada.

Mahādukkhakkhandha Sutta (MN 13) - tradución mellorada

Sobre

o assāda (ilusionismo), ādīnava (desvantaxe) e nissaraṇa (emancipación)

de kāma (sensualidade), rūpa (forma) e vedanā (sentimento). Moita cousa moi útil para reflexionar.

Cūḷahatthipadopama Sutta (MN 27) - tradución mellorada

O Buda explica como o feito de que é realmente un ser iluminado debe

ser tomado na fe ou como unha conxectura ata que se alcance un

determinado estadio e que calquera reclamación de tal coñecemento sen

esa realización sexa inútil.

Mahāvedalla Sutta (MN 43) (extracto) - palabra por palabra

Sāriputta responde a varias preguntas interesantes feitas por Āyasmā

Mahākoṭṭhika e, neste fragmento, explica que Vedanā, Saññā e Viññāṇa non

están claramente delimitadas pero están profundamente entrelazadas.

Cūỏavedalla Sutta (MN 44) {extracto} - tradución mellorada

O bhikkhuni Dhammadinnā responde unha serie de preguntas interesantes formuladas por Visākha. Entre outras cousas, ela dá a definición de 20 veces de sakkāyadiṭṭhi.

Sekha Sutta (MN 53) - tradución mellorada

O Buda pide a Ānanda que expón a Sekha Paṭipadā, da cal dá unha

versión sorprendente, da cal Satisampajañña e Nīvaraṇānaṃ Pahāna son

curiosamente substituídos por unha serie de sete “boas calidades”, e que

se ilustra cun símil contante.

Potaliya Sutta (MN 54) - tradución mellorada

Unha serie de sete similes estándar para explicar os inconvenientes e os perigos de dar sensualidade.

Bahuvedanīya Sutta (MN 59) (extracto) - palabra por palabra

Neste curto fragmento, o Buda define os cinco kāmaguṇās e fai unha comparación importante con outro tipo de pracer.

Kīṭāgiri Sutta (MN 70) {extracto} - tradución mellorada

Este sutta contén unha definición de dhammānusārī e saddhānusārī.

Bāhitikā Sutta (MN 88) {extracto} - tradución mellorada

O Rei Pasenadi de Kosala está ansioso por entender o que se recomenda

ou non por ascetas e brahmanos sabios, e pide unha serie de preguntas a

Ānanda que nos permiten comprender mellor o significado das palabras

kusala (saudable) e akusala (indeciso).

Ānāpānassati Sutta (MN 118) - palabra por palabra

O famoso sutta sobre a práctica do ānāpānassati, e como conduce á

práctica das catro satipaṭṭhānas e subsecuentemente ao cumprimento dos

sete bojjhaṅgas.

Saḷāyatanavibhaṅga Sutta (MN 137) (extracto) - tradución mellorada

Neste profundo e moi interesante sutta, o Buda define entre outras

cousas cales son as investigacións de sentimentos mentais agradables,

desagradables e neutrales, e tamén define a expresión que se atopa na

descrición estándar do Buda: “anuttaro purisadammasārathī”.

Indriyabhāvanā Sutta (MN 152) - palabra por palabra

Este sutta ofrece tres enfoques para a práctica da restrición de

sentido, que conteñen instrucións adicionais que complementan as

fórmulas Indriyesu Guttadvāratā.

—— oooOooo ——

http://www.buddha-vacana.org/sutta/samyutta.html

Árbore

">Saṃyutta Nikāya

- Os discursos clasificados -

[saṃyutta: grupo]

Os discursos do Saṃyutta Nikāya divídense segundo o seu tema en 56 saṃyuttas, que están agrupados en cinco vaggas.

Vibhaṅga Sutta (SN 12.2) - palabra por palabra

Unha explicación detallada da paṭicca samuppāda, cunha definición de cada un dos doce enlaces.

Cetanā Sutta (SN 12.38) - tradución mellorada

Aquí o Buda explica como cetaná, xunto co reflexivo e anusaya, actúan como base para viññāṇa.

Upādāna Sutta (SN 12.52) - tradución mellorada

Esta é unha lección moi esclarecedora que revela mediante a cal o

mecanismo psicolóxico adxudícase e explica como pode ser facilmente

substituído por consideracións saudables para desfacerse del.

Puttamaṃsūpama Sutta (SN 12.63) - tradución mellorada

O Buda ofrece aquí catro similes impresionantes e inspiradores para explicar como deben ser considerados os catro āhāras.

Sanidāna Sutta (SN 14.12) - tradución mellorada

Unha marabillosa explicación de como as percepcións convértense en accións, máis ilustradas polo símil da antorcha ardente. ¡Mantéñase diligentemente consciente de disipar pensamentos inofensivos!

Āṇi Sutta (SN 20.7) - palabra por palabra

Unha

cousa moi importante nos recorda o Buda: para o noso propio beneficio,

así como para o beneficio das xeracións aínda por vencer, debemos darlle

a maior importancia ás súas propias palabras reais, e non tanto a quen

máis finge hoxe en día ou finxiu no pasado para ser un profesor propio (Dhamma).

Samādhi Sutta (SN 22.5) - palabra por palabra

O Buda exhorta aos seus seguidores a que desenvolvan a concentración

para que poidan practicar coñecementos sobre o xurdimento e falecemento

dos cinco agregados, despois de que defina o que significa ao xurdir e

morrer dos agregados, en termos de orixe dependente.

Paṭisallāṇa Sutta (SN 22.6) - sen tradución

O Buda exhorta aos seus seguidores a practicar a reclusión para que

poidan practicar coñecementos sobre o xurdimento e falecemento dos cinco

agregados, despois de que defina o que significa ao xurdir e morrer dos

agregados, en termos de orixe dependente.

Upādāparitassanā Sutta (SN 22,8) - palabra por palabra

A aparición e cesamento do sufrimento ocorre nos cinco agregados.

Nandikkhaya Sutta (SN 22,51) - palabra por palabra

Como operar a destrución de pracer.

Anattalakkhana Sutta (SN 22.59) - palabra por palabra

Neste famoso sutta, o Buda expón por primeira vez o seu ensino sobre anatta.

Khajjanīya Sutta (SN 22.79) {extracto} - palabra por palabra

Este sutta proporciona unha definición sucinta dos cinco khandhas.

Suddhika Sutta (SN 29.1) - tradución mellorada

Os distintos tipos de nāgas.

Suddhika Sutta (SN 30.1) - tradución mellorada

Os diferentes tipos de supaṇṇas (aka garudas).

Suddhika Sutta (SN 31.1) - tradución mellorada

Os diferentes tipos de gandhabba devas.

Suddhika Sutta (SN 32.1) - tradución mellorada

Os diferentes tipos de devas na nube.

Samāpattimūlakaṭhiti Sutta (SN 34.11) - tradución mellorada

Alcanzar a concentración e manter a concentración.

Pubbesambodha Sutta (SN 35.13) - palabra por palabra

O Buda define o seu significado por fascinación, desvantaxe e

emancipación no caso das esferas de sentido interno, e entón declara que

o seu espertar non era nin máis nin menos que entender.

Abhinanda Sutta (SN 35.20) - palabra por palabra

Non hai fuga para quen deleite os obxectos sensuais.

Migajāla Sutta (SN 35.46) - tradución mellorada

Por que a verdadeira soidade é tan difícil de atopar? O Buda explica por que, sen importar onde se vaia, os teus compañeiros máis irritantes sempre agreden.

Avijjāpahāna Sutta (SN 35.53) - palabra por palabra

Un discurso moi sinxelo, aínda veo

Sabbupādānapariññā Sutta (SN 35.60) - palabra por palabra

O Buda, ao expresar a comprensión completa de todo o apego, dá unha

explicación profunda e aínda moi clara: o contacto xorde a partir de

tres fenómenos.

Migajāla Sutta Sutta (SN 35.64) (extracto) - palabra por palabra

Algúns

neófitos (e moitas veces podemos contarnos entre eles) ás veces queren

crer que é posible deleitarse nos praceres sensuais sen dar lugar a

apego ou sufrimento. O Buda ensina a Migajāla que isto é francamente imposible.

Adantāgutta Sutta (SN 35.94) - palabra por palabra

Aquí

está un deses consellos que son tan fáciles de entender co

entendemento, pero tan difíciles de entender en niveis máis profundos

porque as nosas vistas erradas interfiran constantemente no proceso. Polo tanto, necesitamos repetilo a miúdo, aínda que poida parecer aburrido.

Pamādavihārī Sutta (SN 35.97) - palabra por palabra

O que fai a diferenza entre quen vive con neglixencia e quen vive coa vixilancia.

Sakkapañhā Sutta Sutta (SN 35.118) - palabra por palabra

O Buda dá unha resposta bastante simple á pregunta de Sakka: cal é a

razón pola que algunhas persoas alcanzan o obxectivo final mentres que

outras non?

Rūpārāma Sutta (SN 35.137) - palabra por palabra

O Buda explica por nós unha vez máis, de outro xeito, a causa eo cesamento do sufrimento. Ten lugar no medio do que seguimos facendo todo o día e toda a noite.

Aniccanibbānasappāya Sutta (SN 35.147) - palabra por palabra

Aquí están as instrucións de hardcore vipassanā que abordan a

percepción da impermanencia para os meditadores avanzados que esperan

con ansia alcanzar Nibbāna.

Ajjhattānattahetu Sutta (SN 35.142) - palabra por palabra

Como investigar as causas do xurdimento dos órganos sensoriais, en que

a característica de si mesmo non pode ser máis fácil de comprender,

permite a transferencia deste comprensión ao seu caso.

Samudda Sutta (SN 35.229) - tradución mellorada

O que é o océano na disciplina dos nobres. ¡Coidado de non afundir nel!

Pahāna Sutta (SN 36.3) - tradución mellorada

A relación entre os tres tipos de vedanā e tres dos anusayas.

Daṭṭhabba Sutta (SN 36.5) - tradución mellorada

Como se deben ver os tres tipos de vedanā (sentimentos).

Salla Sutta (SN 36.6) - tradución mellorada

Cando

se tira pola frecha da dor física, unha persoa imprudente empeora as

cousas mellorando a angustia mental encima, como se fose disparado por

dúas frechas. Un sabio sente a picadura dunha única frecha.

Anicca Sutta (SN 36.9) - tradución mellorada

Sete características de vedanā (sentimentos), que tamén son aplicables

aos outros catro khandhas (SN 22.21) e cada un dos doce enlaces de

paṭicca · samuppāda (SN 12,20).

Phassamūlaka Sutta (SN 36.10) - palabra por palabra

Os tres tipos de sentimentos están enraizados en tres tipos de contactos.

Aṭṭhasata Sutta (SN 36.22) - tradución mellorada

O Buda expón vedanās de sete xeitos diferentes, analizándoos en dúas,

tres, cinco, seis, dezaoito, trinta e seis ou cen oito categorías.

Nirāmisa Sutta (SN 36.31) (extracto) - palabra por palabra

Podemos entender aquí que o pīti, aínda que moitas veces aparece como bojjhaṅga, tamén pode ser ás veces akusala. Esta pasaxe tamén inclúe unha definición dos cinco kāmaguṇā.

Dhammavādīpañhā Sutta (SN 38.3) - tradución mellorada

Quen profesa o Dhamma no mundo (dhamma · vādī)? Quen practica ben (su · p · paṭipanna)? Quen está saíndo ben (su · gata)?

Dukkara Sutta (SN 39.16) - tradución mellorada

¿Que é difícil facer neste ensino e disciplina?

Vibhaṅga Sutta (SN 45.8) - palabra por palabra

Aquí o Buda define precisamente cada factor do oito e nobre camiño.

Āgantuka Sutta (SN 45.159) - tradución mellorada

Como o Camiño Nobre traballa co abhiññā de varios dhammas como hóspede acollendo varios tipos de visitantes.

Kusala Sutta (SN 46.32) - palabra por palabra

Todo o que é vantaxoso únese nunha cousa.

Āhāra Sutta (SN 46.51) - tradución mellorada

O Buda describe como podemos “alimentar” ou “morrer de fame” os

obstáculos e os factores de iluminación segundo o xeito no que nós

aplicamos a nosa atención.

Saṅgārava Sutta (SN 46.55) (extracto) - tradución mellorada

Unha fermosa serie de similes para explicar como os cinco nīvaraṇas

(obstáculos) afectan a pureza da mente e a súa capacidade de percibir a

realidade tal como é.

Sati Sutta (SN 47.35) - palabra por palabra

Neste sutta, o Buda recorda aos bhikkhus que sexan satos e sampajānos, e entón define estes dous términos.

Vibhaṅga Sutta (SN 47.40) - palabra por palabra

O satipaṭṭhānas ensinou en breve.

Daṭṭhabba Sutta (SN 48.8) - tradución mellorada

Cada un dos cinco indriyas espirituais dise que se pode ver nun dhamma catro veces.

Saṃkhitta Sutta (SN 48.14) - tradución mellorada

O cumprimento dos mesmos é todo o que debemos facer, e esta é a medida da nosa liberación.

Vibhaṅga Sutta (SN 48.38) - tradución mellorada

Aquí o Buda define os cinco indriyas sensibles.

Uppaṭipāṭika Sutta (SN 48.40)

Sāketa Sutta (SN 48.43) (extracto) - tradución mellorada

Neste sutta, o Buda afirma que as balas e os indriyas poden considerarse como unha mesma cousa ou dúas cousas distintas.

Patiṭṭhita Sutta (SN 48.56) - tradución mellorada

Hai un estado mental a través do cal todas as cinco facultades espirituais son perfeccionadas.

Bīja Sutta (SN 49.24) - tradución mellorada

Un fermoso símil que ilustra como é a virtude fundamental para a práctica dos catro esforzos xustos.

Gantha Sutta (SN 50.102) - tradución mellorada

Este sutta está baseado na interesante lista dos catro “nós

corporais”, e promove o desenvolvemento dos cinco puntos fortes

espirituais.

Viraddha Sutta (SN 51.2) - tradución mellorada

Quen descoida estes descoidos o nobre camiño.

Chandasamādhi Sutta (SN 51.13) - tradución mellorada

Este sutta explica claramente o significado das fórmulas que describen a práctica das iddhi · pādas.

Samaṇabrāhmaṇa Sutta (SN 51.17) - tradución mellorada

Mentres no pasado, no futuro ou na actualidade, o que exercerá poderes

supernormales desenvolveu e practicaba asiduamente catro cousas.

Vidhā Sutta (SN 53.36) - tradución mellorada

Recoméndase aos jhānas desfacerse dos tres tipos de presunción, que están relacionados coa comparación cos demais. Faino

claro que, se hai algunha xerarquía na Sangha, é só para fins prácticos

e non debe ser considerado como representativo de ningunha realidade. Non está ben claro se se trata dun sutta repetindo 16 veces o mesmo,

ou 16 suttas agrupados, ou 4 suttas que conteñen cada 4 repeticións.

Padīpopama Sutta (SN 54.8) - palabra por palabra

Aquí o Buda explica ānāpānassati e recoméndalo por varios fins: abandonar as impurezas brutas, ao desenvolver os oito jhānas.

Saraṇānisakka Sutta (SN 55.24) - tradución mellorada

Neste interesante discurso, o Buda afirma que nin sequera ten que ter

unha forte confianza no Buda, Dhamma e Sangha para converterse nun

gañador do fluxo no momento da morte.

Mahānāma Sutta (SN 55.37) - tradución mellorada

O que significa ser un deixe laico laico, dotado de virtude, convicción, xenerosidade e discernimento.

Aṅga Sutta (SN 55.50) - palabra por palabra

Os catro sotāpattiyaṅgas (factores de entrada de fluxo).

Samādhi Sutta (SN 56.1) - palabra por palabra

O Buda exhorta aos bhikkhus a practicar samādhi, pois conduce á

comprensión das catro nobres verdades na súa verdadeira natureza.

Paṭisallāna Sutta (SN 56.2) - palabra por palabra

O Buda exhorta aos bhikkhus a practicar a paṭisallāna, pois conduce á

comprensión das catro nobres verdades na súa verdadeira natureza.

Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta (SN 56.11) - palabra por palabra

Este é sen dúbida o sutta máis famoso da literatura de Pali. O Buda expón os catro ariya-saccas por primeira vez.

Saṅkāsanā Sutta (SN 56.19) - tradución mellorada

A ensinanza das catro verdades nobres, por aburrido que pareza á mente

errante, é realmente moi profunda ea mente pode dedicarse todo o tempo a